Multimetallic Nano-Oxides as Co-Catalysts of an Fe Molecular Catalyst for Enhanced H2 Production from HCOOH: Thermodynamic and Nanostructural Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

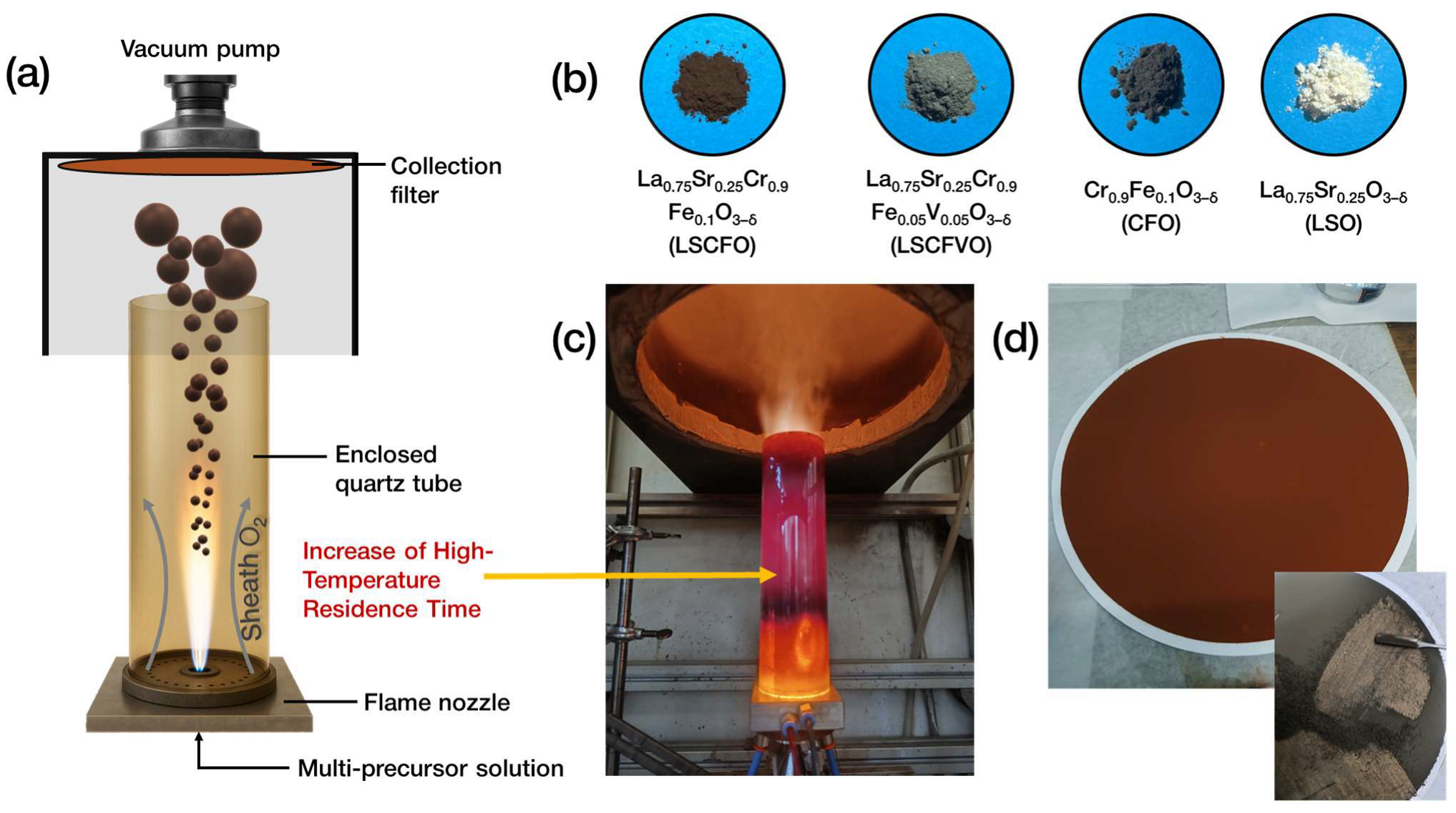

2.1. FSP Engineering of Multimetallic Perovskite Nano–Oxides

2.2. Catalytic H2 Production from HCOOH: Multimetallic Perovskites as Co–Catalysts

2.2.1. The Effect of Co-Catalyst Mass

2.2.2. Solution Potential (Eh) Determination

2.2.3. Evaluation of Thermally-Treated Co-Catalysts

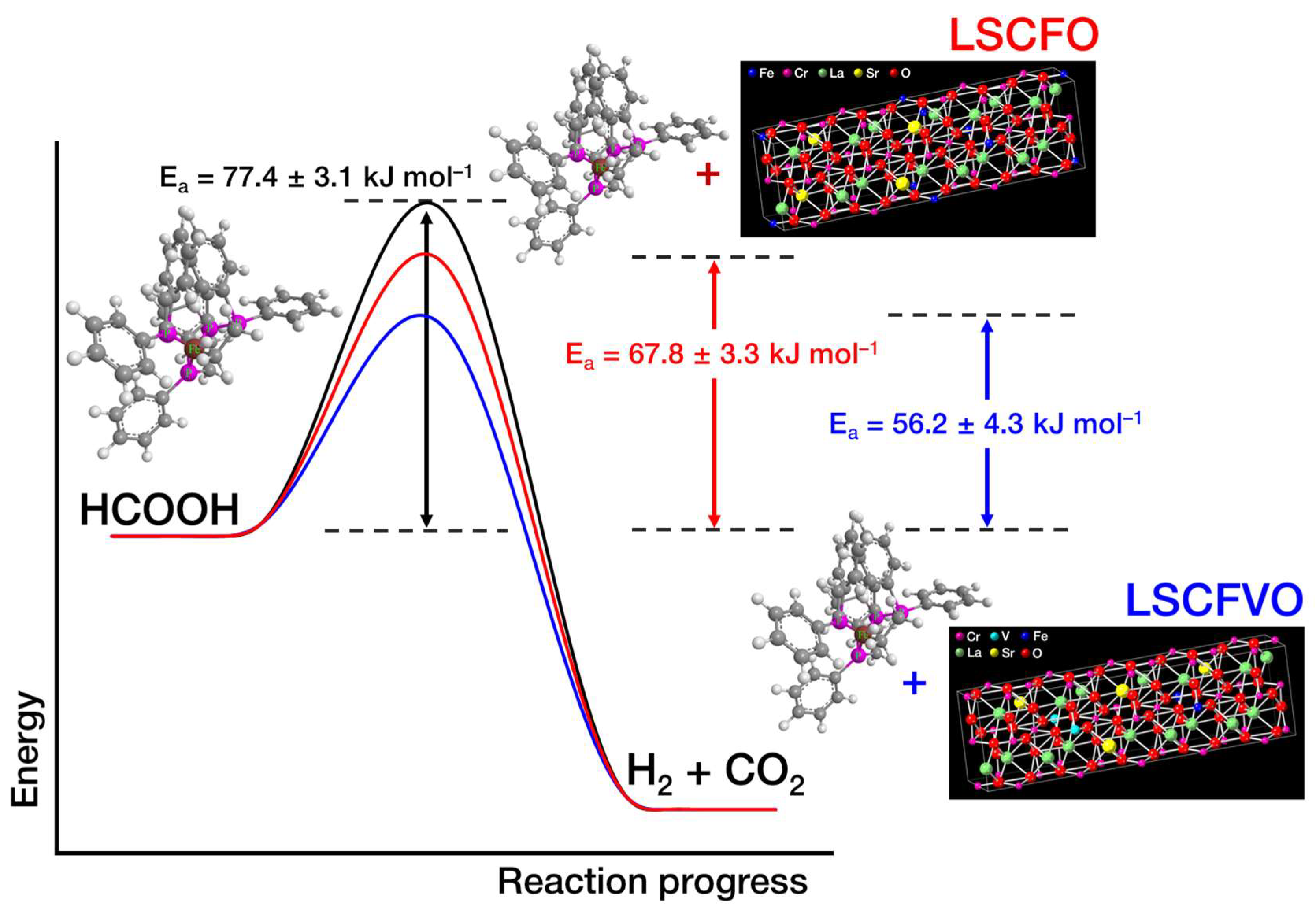

2.3. Thermodynamic Arrhenius Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. One-Step Multimetallic Perovskite Engineering via Flame Spray Pyrolysis

Post-FSP Thermal Treatment

3.2. Characterization of Multimetallic Perovskites

3.3. Catalytic HCOOH/H2 Production Process

3.4. Solution Potential (Eh) Monitoring

3.5. Arrhenius Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eppinger, J.; Huang, K.-W. Formic Acid as a Hydrogen Energy Carrier. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P.M.; Hiete, M.; Sapio, A. Hydrogen Economy and Sustainable Development Goals: Review and Policy Insights. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 31, 100506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modisha, P.M.; Ouma, C.N.M.; Garidzirai, R.; Wasserscheid, P.; Bessarabov, D. The Prospect of Hydrogen Storage Using Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 2778–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hren, R.; Vujanović, A.; Van Fan, Y.; Klemeš, J.J.; Krajnc, D.; Čuček, L. Hydrogen Production, Storage and Transport for Renewable Energy and Chemicals: An Environmental Footprint Assessment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 173, 113113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, F.; Marrocchi, A.; Vaccaro, L. Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHCs) as H-Source for Bio-Derived Fuels and Additives Production. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2103362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddien, A.; Loges, B.; Gärtner, F.; Torborg, C.; Fumino, K.; Junge, H.; Ludwig, R.; Beller, M. Iron-Catalyzed Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 8924–8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qian, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Z.; He, M.; Chen, Q. Application of Heterogeneous Catalysis in Formic Acid-Based Hydrogen Cycle System. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.S.; Adhikary, A. Transition Metal Pincer Catalysts for Formic Acid Dehydrogenation: A Mechanistic Perspective. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1452408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddien, A.; Mellmann, D.; Gärtner, F.; Jackstell, R.; Junge, H.; Dyson, P.J.; Laurenczy, G.; Ludwig, R.; Beller, M. Efficient Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid Using an Iron Catalyst. Science 2011, 333, 1733–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkatziouras, C.; Solakidou, M.; Louloudi, M. Efficient [Fe-Imidazole@SiO2] Nanohybrids for Catalytic H2 Production from Formic Acid. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakopoulos, M.; Solakidou, M.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Louloudi, M. Double-Ligand [Fe/PNP/PP3] and Their Hybrids [Fe/SiO2@PNP/PP3] as Catalysts for H2-Production from HCOOH. Energies 2024, 17, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravvani, K.; Solakidou, M.; Louloudi, M. Highly-Efficient Reusable [Silica@Iminophosphine-FeII ] Hybrids for Hydrogen Production via Formic Acid and Formaldehyde Dehydrogenation. Chem. A Eur. J 2025, 31, e202404440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriou, A.; Aspri, E.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Louloudi, M. Engineering of Hybrid SiO2@{N-P-Fe} Catalysts with Double-Ligand for Efficient H2 Production from HCOOH. Energies 2025, 18, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkatziouras, C.; Solakidou, M.; Louloudi, M. Formic Acid Dehydrogenation over a Recyclable and Self-Reconstructing Fe/Activated Carbon Catalyst. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 17914–17926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkatziouras, C.; Dimitriou, C.; Smykała, S.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Louloudi, M. {Fe2+ –Imidazole} Catalyst Grafted on Magnetic {Fe@Graphitized C} Nanoparticles: A Robust Hybrid–Catalyst for H2 Production from HCOOH. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 21659–21671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathi, P.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Avgouropoulos, G.; Louloudi, M. Efficient H2 Production from Formic Acid by a Supported Iron Catalyst on Silica. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2015, 498, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathi, P.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Louloudi, M. Co-Catalytic Enhancement of H2 Production by SiO2 Nanoparticles. Catal. Today 2015, 242, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathi, P.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Louloudi, M. Co-Catalytic Effect of Functionalized SiO2 Materials on H2 Production from Formic Acid by an Iron Catalyst. MRS Proc. 2014, 1641, mrsf13-1641-aa06-26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solakidou, M.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Louloudi, M. Heterogeneous Amino-Functionalized Particles Boost Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid by a Ruthenium Complex. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 21386–21397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solakidou, M.; Theodorakopoulos, M.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Louloudi, M. Double-Ligand Fe, Ru Catalysts: A Novel Route for Enhanced H2 Production from Formic Acid. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 17367–17377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemenetzi, A.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Louloudi, M. Controlled Photoplasmonic Enhancement of H2 Production via Formic Acid Dehydrogenation by a Molecular Fe Catalyst. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 9905–9917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakopoulos, M.; Deligiannakis, Y.; Louloudi, M. Solution-Potential and Solution-Hydrides as Key-Parameters in H2 Production via HCOOH-Dehydrogenation by Fe- and Ru-Molecular Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 58, 1608–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo-Garzon, F.; Wu, Z. Acid–Base Catalysis over Perovskites: A Review. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 2877–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Bjørgum, E.; Mihai, O.; Yang, J.; Lein, H.L.; Grande, T.; Raaen, S.; Zhu, Y.-A.; Holmen, A.; Chen, D. Effects of Oxygen Mobility in La–Fe-Based Perovskites on the Catalytic Activity and Selectivity of Methane Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 3707–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhoeve, R.J.H.; Johnson, D.W.; Remeika, J.P.; Gallagher, P.K. Perovskite Oxides: Materials Science in Catalysis. Science 1977, 195, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasleem, S.; Tahir, M. Recent Progress in Structural Development and Band Engineering of Perovskites Materials for Photocatalytic Solar Hydrogen Production: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 19078–19111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Rao, R.R.; Giordano, L.; Katayama, Y.; Yu, Y.; Shao-Horn, Y. Perovskites in Catalysis and Electrocatalysis. Science 2017, 358, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, A.; Kim, J.; Shin, J.; Kim, G. Perovskite as a Cathode Material: A Review of Its Role in Solid-Oxide Fuel Cell Technology. ChemElectroChem 2016, 3, 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, M.; Bork, A.H.; Rupp, J.L.M. Perovskite Oxides—A Review on a Versatile Material Class for Solar-to-Fuel Conversion Processes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 11983–12000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tadé, M.O.; Shao, Z. Research Progress of Perovskite Materials in Photocatalysis- and Photovoltaics-Related Energy Conversion and Environmental Treatment. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 5371–5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karageorgakis, N.I.; Heel, A.; Bieberle-Hütter, A.; Rupp, J.L.M.; Graule, T.; Gauckler, L.J. Flame Spray Deposition of La0.6Sr0.4CoO3−δ Thin Films: Microstructural Characterization, Electrochemical Performance and Degradation. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 8152–8161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Wang, Q.; Schiele, A.; Chellali, M.R.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Wang, D.; Brezesinski, T.; Hahn, H.; Velasco, L.; Breitung, B. High-Entropy Oxides: Fundamental Aspects and Electrochemical Properties. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albedwawi, S.H.; AlJaberi, A.; Haidemenopoulos, G.N.; Polychronopoulou, K. High Entropy Oxides-Exploring a Paradigm of Promising Catalysts: A Review. Mater. Des. 2021, 202, 109534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamlid, S.S.; Oudah, M.; Rottler, J.; Hallas, A.M. Understanding the Role of Entropy in High Entropy Oxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 5991–6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O.N. A Critical Review of High Entropy Alloys and Related Concepts. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-W.; Chen, S.-K.; Lin, S.-J.; Gan, J.-Y.; Chin, T.-S.; Shun, T.-T.; Tsau, C.-H.; Chang, S.-Y. Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys with Multiple Principal Elements: Novel Alloy Design Concepts and Outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A.J.B. Microstructural Development in Equiatomic Multicomponent Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375–377, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, C.M.; Sachet, E.; Borman, T.; Moballegh, A.; Dickey, E.C.; Hou, D.; Jones, J.L.; Curtarolo, S.; Maria, J.-P. Entropy-Stabilized Oxides. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, S.J.; Navrotsky, A. Thermodynamics of High Entropy Oxides. Acta Mater. 2021, 202, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandkumar, M.; Trofimov, E. Synthesis, Properties, and Applications of High-Entropy Oxide Ceramics: Current Progress and Future Perspectives. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 960, 170690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.J.; Luo, J. A Step Forward from High-Entropy Ceramics to Compositionally Complex Ceramics: A New Perspective. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 9812–9827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahlek, M.; Gazda, M.; Keppens, V.; Mazza, A.R.; McCormack, S.J.; Mielewczyk-Gryń, A.; Musico, B.; Page, K.; Rost, C.M.; Sinnott, S.B.; et al. What Is in a Name: Defining “High Entropy” Oxides. APL Mater. 2022, 10, 110902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.-T.; Lee, T.; Qi, J.; Zhang, D.; Peng, W.-T.; Wang, X.; Tsai, W.-C.; Sun, S.; Wang, Z.; Bowman, W.J.; et al. Compositionally Complex Perovskite Oxides: Discovering a New Class of Solid Electrolytes with Interface-Enabled Conductivity Improvements. Matter 2023, 6, 2395–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; De Santiago, H.A.; Xu, B.; Liu, C.; Trindell, J.A.; Li, W.; Park, J.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Coker, E.N.; Sugar, J.D.; et al. Compositionally Complex Perovskite Oxides for Solar Thermochemical Water Splitting. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 1901–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Du, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhao, H. Medium-Entropy Perovskites Sr(FeαTiβCoγMnζ)O3-δ as Promising Cathodes for Intermediate Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cell. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 295, 120264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tuo, P.; Dai, F.-Z.; Yu, Z.; Lai, W.; Ding, Q.; Yan, P.; Gao, J.; Hu, Y.; Hu, Y.; et al. A Highly Deficient Medium-Entropy Perovskite Ceramic for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding under Harsh Environment. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2400059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shi, C.; Zhang, G.; Zheng, G.; Huang, Z.; Shen, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, T.; Wang, S. A Medium-Entropy Perovskite Oxide La0.7Sr0.3Co0.25Fe0.25Ni0.25Mn0.25O3-δ as Intermediate Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells Cathode Material. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 30187–30195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquirol, A.; Brandon, N.P.; Kilner, J.A.; Mogensen, M. Electrochemical Characterization of La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8 O 3 Cathodes for Intermediate-Temperature SOFCs. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2004, 151, A1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Q.; Li, J.-H.; Sun, Y.-F.; Hua, B.; Luo, J.-L. Highly Active and Redox-Stable Ce-Doped LaSrCrFeO-Based Cathode Catalyst for CO2 SOECs. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 6457–6463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gan, L. Exsolved Metallic Iron Nanoparticles in Perovskite Cathode to Enhance CO2 Electrolysis. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2022, 26, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimpiri, N.; Konstantinidou, A.; Papazisi, K.M.; Balomenou, S.; Tsiplakides, D. Electrochemical Performance of Iron Doped Lanthanum Strontium Chromites as Fuel Electrodes in High Temperature Solid Oxide Cells. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 475, 143537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psathas, P.; Georgiou, Y.; Moularas, C.; Armatas, G.S.; Deligiannakis, Y. Controlled-Phase Synthesis of Bi2Fe4O9 & BiFeO3 by Flame Spray Pyrolysis and Their Evaluation as Non-Noble Metal Catalysts for Efficient Reduction of 4-Nitrophenol. Powder Technol. 2020, 368, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psathas, P.; Moularas, C.; Smykała, S.; Deligiannakis, Y. Highly Crystalline Nanosized NaTaO3/NiO Heterojunctions Engineered by Double-Nozzle Flame Spray Pyrolysis for Solar-to-H2 Conversion: Toward Industrial-Scale Synthesis. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 2658–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moularas, C.; Psathas, P.; Deligiannakis, Y. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Study of Photo-Induced Hole/Electron Pairs in NaTaO3 Nanoparticles. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 782, 139031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Bi, W.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, M.; et al. Hydrogen-Bond Network Mediated Lattice-Strain Engineering for CO2-to-CH4 Selectivity Regulation via Flame Spray Pyrolysis Strategy. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2026, 703, 139159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Ju, J.; Wu, Y.; Wan, X.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Jiang, H.; Hu, Y.; Li, C. Lattice-Strain Engineering of High-Entropy-Oxide Nanoparticles: Regulation by Flame Spray Pyrolysis with Ultrafast Quenching. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2418856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, C.; Psathas, P.; Solakidou, M.; Deligiannakis, Y. Advanced Flame Spray Pyrolysis (FSP) Technologies for Engineering Multifunctional Nanostructures and Nanodevices. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriou, C.; Belles, L.; Boukos, N.; Deligiannakis, Y. {TiO2/TiO2(B)} Quantum Dot Hybrids: A Comprehensible Route toward High-Performance [>0.1 Mol Gr–1 h–1] Photocatalytic H2 Production from H2O. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 17919–17934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phakatkar, A.; Saray, M.; Rasul, M.G.; Sorokina, L.; Ritter, T.; Shokuhfar, T.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R. Ultrafast Synthesis of High Entropy Oxide Nanoparticles by Flame Spray Pyrolysis. Langmuir 2021, 37, 9059–9068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Ju, J.; Luo, L.; Jiang, H.; Hu, Y.; Li, C. Flame Spray Pyrolysis Synthesis of Ultra-Small High-Entropy Alloy-Supported Oxide Nanoparticles for CO2 Hydrogenation Catalysts. Small Methods 2024, 8, 2301768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, X.; Huang, Z.; Lin, H. One-Step Synthesis of Pt@(CrMnFeCoNi)3O4 High Entropy Oxide Catalysts through Flame Spray Pyrolysis. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 117, 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, C.; Deligiannakis, Y. Thermoplasmonic Nano–Hybrid Core@Shell Ag@SiO2 Films Engineered via One–Step Flame Spray Pyrolysis. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zschornack, G. Handbook of X-Ray Data; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawazoe, Y.; Kanomata, T.; Note, R. LaCrO3. In High Pressure Materials Properties: Magnetic Properties of Oxides Under Pressure: A Supplement to Landolt-Börnstein IV/22 Series; Kawazoe, Y., Kanomata, T., Note, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtig, N.C.; Gysi, A.P.; Smith-Schmitz, S.E.; Harlov, D. Raman Spectroscopic Study of Anhydrous and Hydrous REE Phosphates, Oxides, and Hydroxides. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 9964–9978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, J.H.; Ross, S.D. The Vibrational Spectra and Structures of Rare Earth Oxides in the A Modification. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1972, 5, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldish, S.I.; White, W.B. Vibrational Spectra of Crystals with the A-Type Rare Earth Oxide Structure—I. La2O3 and Nd2O3. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Spectrosc. 1979, 35, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.-H.; Duffy, T.S.; Jeanloz, R.; Yoo, C.-S.; Iota, V. Raman Spectroscopy and X-Ray Diffraction of Phase Transitions in Cr2O3 to 61 GPa. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 144107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.S.O.; Yaghini, N.; Martinelli, A.; Ahlberg, E. A Micro-Raman Spectroscopic Study of Cr(OH)3 and Cr2O3 Nanoparticles Obtained by the Hydrothermal Method. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2017, 48, 1256–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, P.; Singh, J.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, D.; Verma, V.; Kumar, R. Oxygen Defects Induced Tailored Optical and Magnetic Properties of FexCr2−xO3 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.1) Nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. A 2022, 128, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.C.; Kreisel, J.; Thomas, P.A.; Newton, M.; Sardar, K.; Walton, R.I. Phonon Raman Scattering of RCrO3 Perovskites (R=Y, La, Pr, Sm, Gd, Dy, Ho, Yb, Lu). Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 054303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadram, V.S.; Sen, A.; Sunil, J.; Panda, D.P.; Sundaresan, A.; Narayana, C. Pressure-Driven Evolution of Structural Distortions in RCrO3 Perovskites: The Curious Case of LaCrO3. Solid State Sci. 2021, 119, 106708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, M.N.; Litvinchuk, A.P.; Hadjiev, V.G.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Cmaidalka, J.; Meng, R.-L.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Kolev, N.; Abrashev, M.V. Raman Spectroscopy of Low-Temperature (Pnma) and High-Temperature (R3c) Phases of LaCrO3. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 214301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, K.D.; Kumar, R. Effect of Sr Substitution on Structural Properties of LaCrO3 Perovskite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 12039–12052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.D.; Pandit, R.; Kumar, R. Effect of Rare Earth Ions on Structural and Optical Properties of Specific Perovskite Orthochromates; RCrO3 (R = La, Nd, Eu, Gd, Dy, and Y). Solid State Sci. 2018, 85, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuermann, W.; Ritter, G.J. The Vibrational Spectra of Strontium Chromate (SrCrO4) and Lead Chromate (PbCrO4). Z. Für. Naturforschung A 1970, 25, 1856–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompsett, G.A.; Sammes, N.M. Characterisation of the SOFC Material, LaCrO3, Using Vibrational Spectroscopy. J. Power Sources 2004, 130, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrejoiu, I.; Himcinschi, C.; Jin, L.; Jia, C.-L.; Raab, N.; Engelmayer, J.; Waser, R.; Dittmann, R.; van Loosdrecht, P.H.M. Probing Orbital Ordering in LaVO3 Epitaxial Films by Raman Scattering. APL Mater. 2016, 4, 046103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, S.; Fujioka, J.; Iwama, M.; Okimoto, Y.; Tokura, Y. Raman Study of Spin and Orbital Order and Excitations in Perovskite-Type RVO3 (R = La, Nd, and Y). Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 224436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.L.; Palmer, S.J.; Čejka, J.; Sejkora, J.; Plášil, J.; Bahfenne, S.; Keeffe, E.C. A Raman Spectroscopic Study of the Different Vanadate Groups in Solid-State Compounds—Model Case: Mineral Phases Vésigniéite [BaCu3(VO4)2(OH)2] and Volborthite [Cu3V2O7(OH)2·2H2O]. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2011, 42, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, K.; Samad, R.; Najar, F.A.; Abass, S.; Jahan, S.; Rashid Rather, M.; Ikram, M. Structural, Optical and Dielectric Properties of Sr Doped LaVO4. Adv. Mater. Lett. 2021, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, H.; Shukla, R.; Dhaka, R.S. Structural Phase Transition and Its Consequences for the Optical Behavior of LaV1-xNbxO4. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 174107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlouf, S.A.; Bakr, Z.H.; Al-Attar, H.; Moustafa, M.S. Structural, Morphological and Electrical Properties of Cr2O3 Nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2013, 178, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiljanić, S.; Karamanova, E.; Grujić, S.; Rogan, J.; Stojanović, J.; Matijašević, S.; Karamanov, A. Sintering, Crystallization and Foaming of La2O3·Sr 5B2O3 Glass Powders—Effect of the Holding Temperature and the Heating Rate. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2018, 481, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, W.M. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 97th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, W.V.; Chirico, R.D.; Cowell, A.B.; Knipmeyer, S.E.; Nguyen, A. Thermodynamic Properties and Ideal-Gas Enthalpies of Formation for 2-Aminoisobutyric Acid (2-Methylalanine), Acetic Acid, (Z)-5-Ethylidene-2-Norbornene, Mesityl Oxide (4-Methyl-3-Penten-2-One), 4-Methylpent-1-Ene, 2,2′-Bis(Phenylthio)Propane, and Glycidyl Phenyl Ether (1,2-Epoxy-3-Phenoxypropane). J. Chem. Eng. Data 1997, 42, 1053–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A.L. The Scherrer Formula for X-Ray Particle Size Determination. Phys. Rev. 1939, 56, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | FSP Nominal Configuration | Crystallographic Phase (XRD, PDF) | XRF-Determined Stoichiometry | dXRD (nm) (±0.5) | SSA (m2 gr−1) (±1) | Pore Volume (cm3 gr−1) (±0.005) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-prepared | ||||||

| LSCFO | La0.75Sr0.25Cr0.9Fe0.1O3–δ | La0.9Sr0.1Cr0.8Fe0.2O3 | La0.83Sr0.17Cr0.91Fe0.09O3 | 65 | 11 | 0.073 |

| LSCFVO | La0.75Sr0.25Cr0.9Fe0.05V0.05O3–δ | La0.95Sr0.05Cr0.9Fe0.06V0.04O3 | 75 | 13 | 0.096 | |

| LSO | La0.75Sr0.25O3−δ | 90% La2O3 + 10% La-Sr-O | La0.88Sr0.12O3 | 50 | 12 | 0.043 |

| CFO | Cr0.9Fe0.1O3−δ | Cr2O3 | Cr0.91Fe0.09O3 | 40 | 37 | 0.261 |

| Post-FSP treated | ||||||

| LSCFO-c | LSCFO calcined at 400 °C for 2h in air | La0.9Sr0.1Cr0.8Fe0.2O3 | – | 65 | – | – |

| LSCFVO-c | LSCFVO calcined at 400 °C for 2h in air | – | 76 | – | – | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dimitriou, C.; Gravvani, K.; Asvestas, A.; Anagnostopoulos, D.F.; Louloudi, M.; Deligiannakis, Y. Multimetallic Nano-Oxides as Co-Catalysts of an Fe Molecular Catalyst for Enhanced H2 Production from HCOOH: Thermodynamic and Nanostructural Insights. Catalysts 2026, 16, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010044

Dimitriou C, Gravvani K, Asvestas A, Anagnostopoulos DF, Louloudi M, Deligiannakis Y. Multimetallic Nano-Oxides as Co-Catalysts of an Fe Molecular Catalyst for Enhanced H2 Production from HCOOH: Thermodynamic and Nanostructural Insights. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimitriou, Christos, Konstantina Gravvani, Anastasios Asvestas, Dimitrios F. Anagnostopoulos, Maria Louloudi, and Yiannis Deligiannakis. 2026. "Multimetallic Nano-Oxides as Co-Catalysts of an Fe Molecular Catalyst for Enhanced H2 Production from HCOOH: Thermodynamic and Nanostructural Insights" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010044

APA StyleDimitriou, C., Gravvani, K., Asvestas, A., Anagnostopoulos, D. F., Louloudi, M., & Deligiannakis, Y. (2026). Multimetallic Nano-Oxides as Co-Catalysts of an Fe Molecular Catalyst for Enhanced H2 Production from HCOOH: Thermodynamic and Nanostructural Insights. Catalysts, 16(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010044