Performance and Mechanism of Monolithic Co-Doped Nickel–Iron Foam Catalyst for Highly Efficient Activation of PMS in Degrading Chlortetracycline in Water

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization

2.1.1. XRD and FT-IR

2.1.2. SEM and TEM Analysis

2.2. Performance Analysis of N-101-NFF (Co0.05)

2.2.1. Reaction Parameters

2.2.2. Effects of Reaction Conditions

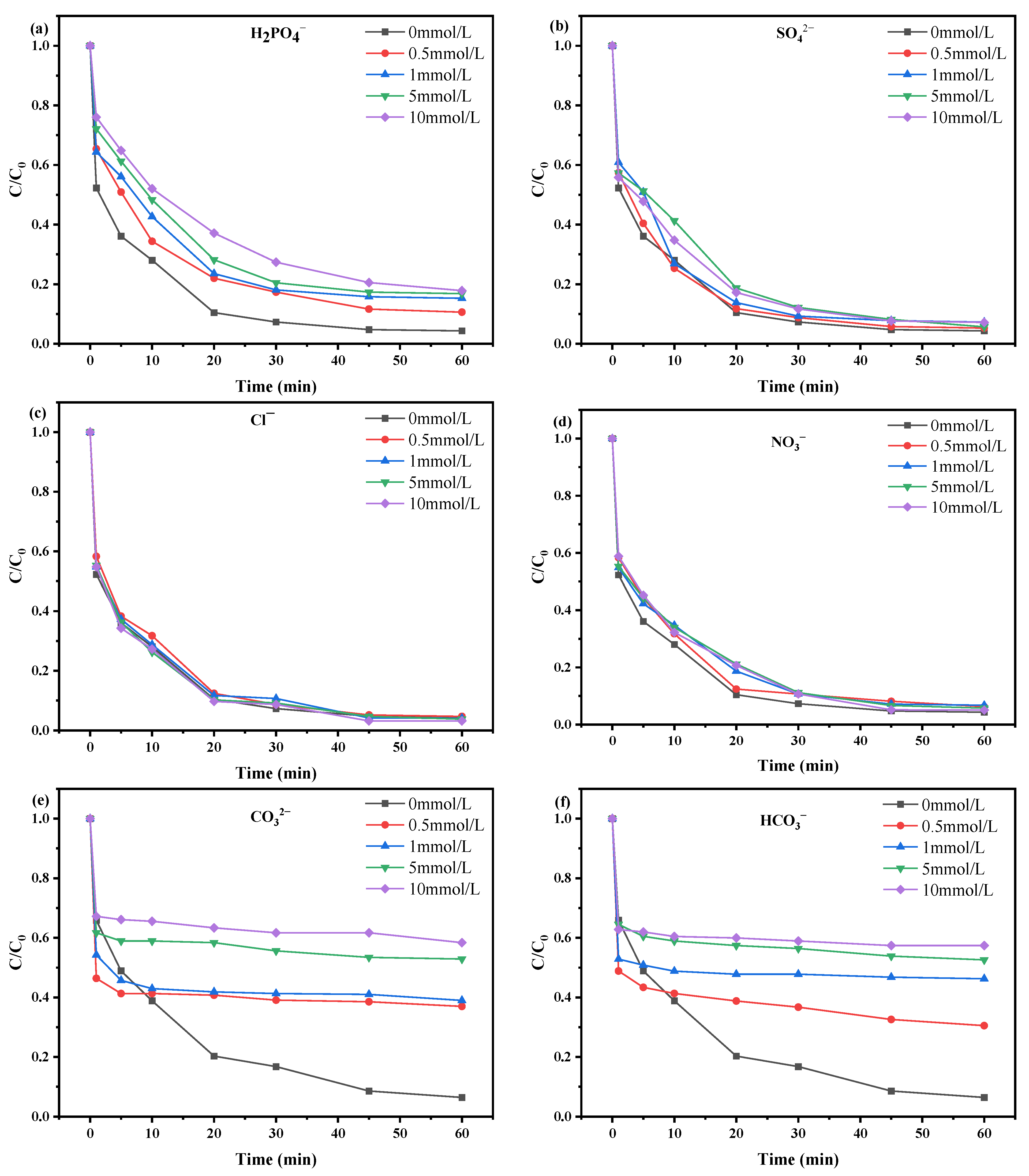

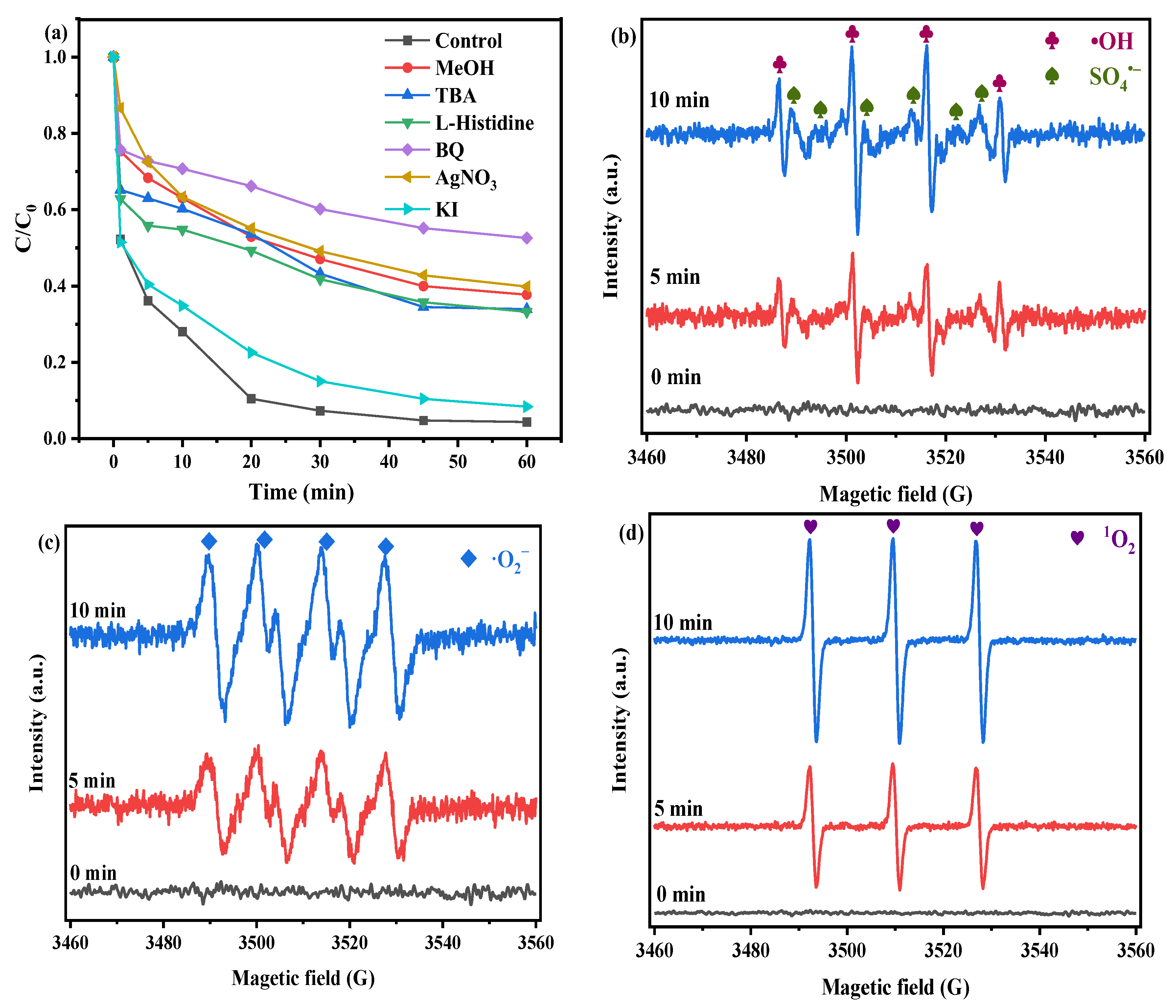

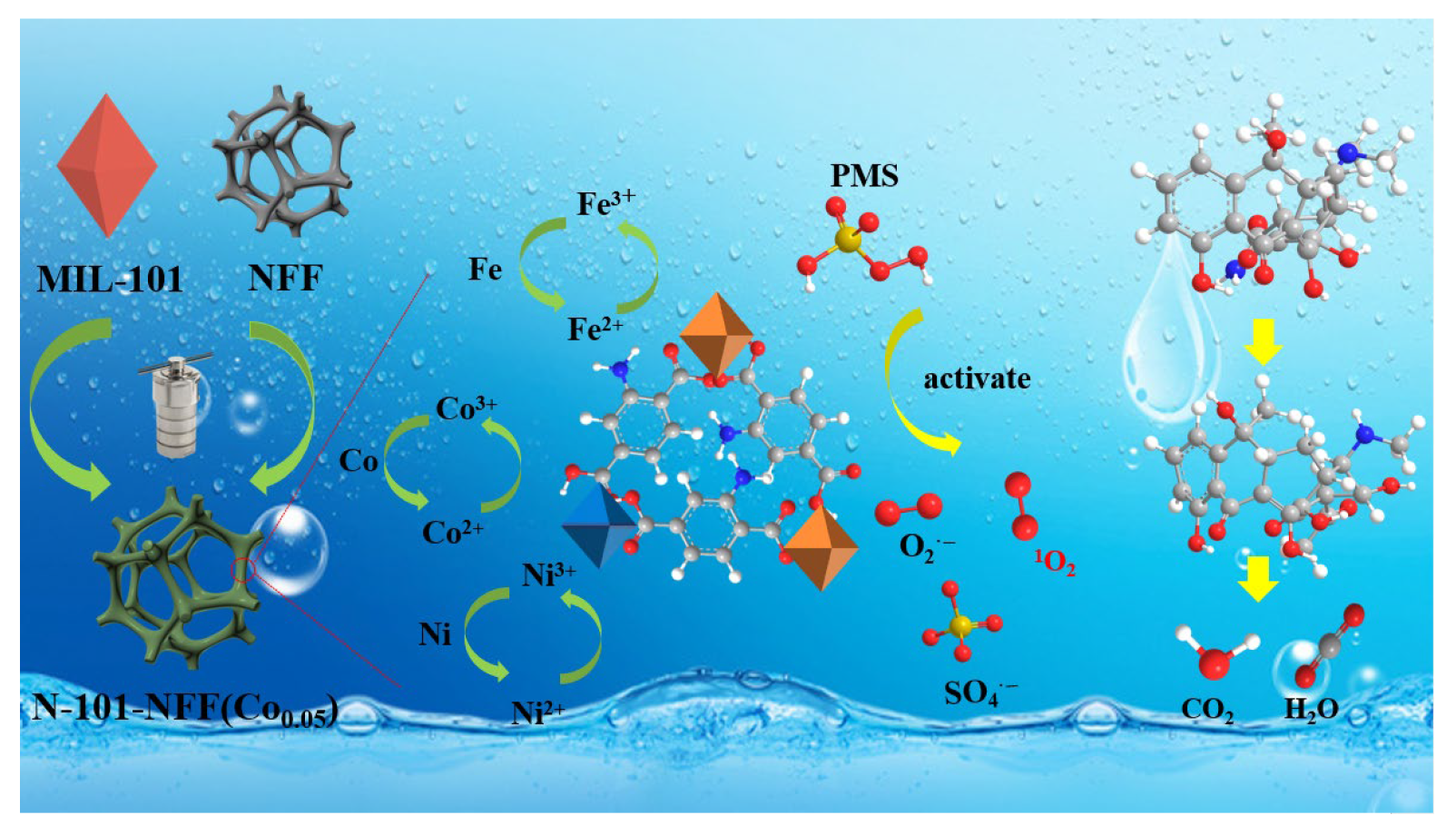

2.3. Research on Degradation Mechanism

2.3.1. Identification of Active Species

2.3.2. Electronic Transfer Mechanism

2.3.3. Characterization of Catalyst After Reaction

2.3.4. Catalytic Reaction Mechanism

2.4. Degradation Pathway and Toxicity Assessment

2.4.1. Degradation Pathway of CTC

2.4.2. Toxicity Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Materials

3.2. Preparation of Catalyst

3.2.1. Pretreatment of Nickel–Iron Foam

3.2.2. Preparation of N-101-NFF (Cox)

3.3. Characterization and Degradation Experiments

4. Fixed Bed Application of the System

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hain, E.; Adejumo, H.; Anger, B.; Orenstein, J.; Blaney, L. Advances in antimicrobial activity analysis of fluoroquinolone, macrolide, sulfonamide, and tetracycline antibiotics for environmental applications through improved bacteria selection. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 415, 125686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Liu, R.; Gao, W.; Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, N. CuFe2O4/penicillin residue biochar heterogeneous Fenton-like catalyst used in the treatment of antibiotic wastewater: Synthesis, performance and working mechanism. J. Water Process. Eng. 2023, 55, 104124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Sun, Z.; Hao, P.; Hu, Y.; Yang, W.; Quan, R.; et al. MOF derived highly dispersed bimetallic Fe-Ni nitrogen-doped carbon for enhanced peroxymonosulfate activation and tetracycline degradation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-X.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wei, S.; Cowie, B.C.; Marshall, A.T.; Wang, Z.; Waterhouse, G.I. Divalent site doping of NiFe-layered double hydroxide anode catalysts for enhanced anion-exchange membrane water electrolysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 508, 160753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Tian, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Dai, W.; Quan, G.; Lei, J.; Zhang, X.; Tang, L. Three-dimensional MIL-88A(Fe)-derived α-Fe2O3 and graphene composite for efficient photo-Fenton-like degradation of ciprofloxacin. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 111063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, B.; Gao, X.; Dang, X.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, X. MOF-on-MOF composite material derived from ZIF-67 precursor activated by peroxymonosulfate for the removal of metronidazole. J. Water Process. Eng. 2025, 72, 107467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y.; Hu, B.; Huang, S.; Zhang, X.; Lei, J.; Liu, N. In situ electronic modulation of g-C3N4/UiO66 composites via N species functionalized ligands for enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 134964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Buren, T.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ma, S.; Wei, J.; Bi, F.; Zhang, X. Electron beam irradiation defective UiO-66 supported noble metal catalysts for binary VOCs removal: Insight into the synergistic degradation mechanism of mutual promotion. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 380, 135236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.; Feng, X.; Huang, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, H.; Du, Q.; Liu, N.; Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; et al. Unveiling the Influence Mechanism of Impurity Gases on Cl-Containing Byproducts Formation during VOC Catalytic Oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 15526–15537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, Z.; Guo, M.; Lu, Z.; Bi, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Study on the difference in catalytic performance and chlorine-resistance of Universitetet i Oslo-derived M@ZrO2 (M = Pd, Pt) catalysts for o-Xylene degradation. Mater. Today Chem. 2025, 49, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ye, J.; Zhai, Y.; Yang, B.; Yin, M.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. ZIF-67-derived monolithic bimetallic sulfides as efficient persulfate activators for the degradation of ofloxacin. Surfaces Interfaces 2024, 51, 104713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Guo, S.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Quan, G.; Zhang, X.; Lei, J.; Liu, N. Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalysis of ibuprofen by NH2 modified MIL-53(Fe) graphene aerogel: Performance, mechanism, pathway and toxicity assessment. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 726, 137769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhou, D.; Tang, K.; Ma, Y.; Han, T.; Lei, J.; Huang, S.; Zhang, X.; Tang, L.; et al. Electron beam- induced defect engineering construction in MIL-68(In) for enhanced CO2 photoreduction: Unravelling organic framework defects. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 702, 138990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, W.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Ma, L. Advanced treatment of industrial wastewater by ozonation with iron-based monolithic catalyst packing: From mechanism to application. Water Res. 2023, 235, 119860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, R.; Muneer, M.; Khalid, R.; Amin, H.M.A. ZnO-Bi2O3 Heterostructured Composite for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Orange 16 Reactive Dye: Synergistic Effect of UV Irradiation and Hydrogen Peroxide. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, Y.; Li, Q.; Jiang, X.; Huang, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhao, H.; Jing, G.; Shen, H. Remarkable performance of N-doped carbonization modified MIL-101 for low-concentration benzene adsorption. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 289, 120784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhang, M.; Shen, Y.; Liang, X.; Jiao, W.; He, R.; Zou, Y.; Chen, H.; Zou, X. Room-Temperature, Meter-Scale Synthesis of Heazlewoodite-Based Nanoarray Electrodes for Alkaline Water Electrolysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2400979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Liu, J.; Shao, L.; Shi, X.; Xu, J.; Guo, W.; Sun, Z.; Chen, C.; Hang, L. Regulating d–p Orbital Hybridized Electronic Structure via Doping Engineering for Advanced Sodium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 38089–38099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; An, L.; Li, P.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qu, D.; Liu, Y.; Hu, P.; Wang, X.; Jiang, N.; et al. Regulating electronic density and interfacial electric field of high-entropy metallenes to enhance oxygen reduction reaction activity. Chem Catal. 2025, 5, 101357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; He, M.; Zhang, C.; Zuo, G.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; He, H. MOFs-derived Fe Ni bimetallic phosphide with tightly coupled heterogeneous interface for PMS activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 166974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Zhu, Q.; Hou, G.; Pang, Z.; Kang, H. Pinning effect of lattice co enhances lattice oxygen regeneration in NiFe-LDH for oxygen evolution reaction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 699, 138219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oglou, R.C.; Ceccato, M.; Frederiksen, M.L.; Shavorskiy, A.; Bentien, A.; Lauritsen, J.V. Depth-Profiling Cation Location and Oxidation States of Ni Foam Electrodes in Fe/Co-Enriched Electrolytes under Alkaline Water Oxidation Conditions. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 17122–17132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhang, R.; Han, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, C.; Li, C.; Xue, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Gan, J.; et al. Unraveling 3d Transition Metal (Ni, Co, Mn, Fe, Cr, V) Ions Migration in Layered Oxide Cathodes: A Pathway to Superior Li-Ion and Na-Ion Battery Cathodes. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2413760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Fan, S.; Long, H.; Fan, Q.; Duan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Z. The anodic chlorine ion repelling mechanisms of Fe/Co/Ni-based nanocatalysts for seawater electrolytic hydrogen production. Nano Energy 2025, 135, 110662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, K.; Zhao, S.; Xue, J. Precise control of cobalt active site size to switch ROS pathways: Millimeter-scale carbon beads derived from dual MOFs for targeted degradation of drug pollutants. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2025, 383, 126046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Zhong, W.; Li, C.; Xia, Y.; Zhu, Q. TiO2-loaded porphyrin-like metal-organic framework as a heterojunction-peroxymonosulfate activated co-catalyst for bisphenol A removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lv, Z.; Deng, J.; Cao, T.; Kim, M.; Kang, H.; Wang, J.; Peng, R.; Zhu, X.; Mao, Y. ZIF-67-natural sponge derived macroarchitectures as efficient catalytic converters for 4-nitrophenol removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yao, J.; Yin, L.; Wang, B.; Liu, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, C.; Bao, T.; Liu, C.; Hu, X. Facet engineering of metal-organic frameworks for efficient tetracycline degradation by photocatalytic activation of peroxymonosulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, T.; Shao, B.; He, Q.; Zhou, L.; Li, T.; Liu, S.; Huang, X.; et al. MOF derived MnFeOX supported on carbon cloth as electrochemical anode for peroxymonosulfate electro-activation and persistent organic pollutants degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Smith, R.L.; Guo, H.; Zhao, R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, F.; Ding, Y. Insights into the mechanism of mechanically treated Fe/Mn-N doped seed meal hydrochar for efficient adsorption and degradation of tetracycline. Biochar 2025, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.J.; Ashizawa, M.; McLean, A.M.; Serrano, R.R.; Shimura, T.; Agetsuma, M.; Tsutsumi, M.; Nemoto, T.; Parmenter, C.D.J.; McCune, J.A.; et al. Supramolecular Conductive Hydrogels With Homogeneous Ionic and Electronic Transport. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2415687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, A.; Lu, J.; Liu, T.; Feng, C.; Liu, Y.; Pang, J.; Chen, L.; Wu, Z.; Han, S.; Li, Z. Characterization and mechanism of action of bimetallic-modified MIL-101(Fe) magnetic composites for enhanced removal of polystyrene from water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 372, 133397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Liu, Z.; Rae, R.; Santori, G.; Lau, C.H.; Qian, J.; Fan, X. Synergistic effects of salt and MIL-101(Cr) in composites: Unravelling the moisture pump-reservoir mechanism for efficient atmospheric water harvesting. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Lu, J.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, Z. Organic ligand-engineered MOFs-derived spinel CoMn2O4 with tailored nanostructures and chemical properties for synergistic low-temperature removal of NOx and VOCs. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saady, N.M.C.; Sivaraman, S.; Venkatachalam, P.; Zendehboudi, S.; Zhang, Y.; Palma, R.Y.; Shanmugam, S.R.; Espinoza, J.E.R. Effect of veterinary antibiotics on methane yield from livestock manure anaerobic digestion: An analytical review of the evidence. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technology 2024, 23, 133–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; Wu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Lei, T.; Huang, J.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wei, Y.; Chen, M. Enhanced removal of Mn2+ and NH4+-N in electrolytic manganese metal residue using washing and electrolytic oxidation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 270, 118798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Hu, H.; Tong, X.; Duan, Y. Catalytic oxidation of peroxymonosulfate by Co/Fe loaded carbon nitride on oxidising SO32− and inhibiting Hg0 release in solution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 374, 133682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Miao, R.; Wang, J.; Sun, H.; Hao, J. Selective separation of Ni2+/Co2+/Mn2+ enabled by tunable intrapore sulfonic acid group content in covalent organic framework membranes via EDTA-chelation-assisted process. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 732, 124252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Cheng, X.; Xu, T.; Chen, K.; Xiang, H.; Su, L. Crystalline boron significantly accelerates Fe(III)/PMS reaction as an electron donor: Iron recycling, reactive species generation, and acute toxicity evaluation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 452, 139154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebstock, J.A.; Rao, A.; Samanta, A.; Asthagiri, A.; Baker, L.R. Specifically Adsorbed Carbonate Ions and Copper Surface Reconstruction: The Effect of Double Layer Charging Revealed by Time-Resolved Sum Frequency Generation Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 41404–41412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Spear, N.J.; Cummings, A.J.; Khusainova, K.; Macdonald, J.E.; Haglund, R.F. Harmonic-induced plasmonic resonant energy transfer between metal and semiconductor nanoparticles. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadv1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; He, C.; Pang, J.; Zhang, L.; Tang, F.; Yang, X. Recognizing the relevance of non-radical peroxymonosulfate activation by co-doped Fe metal-organic framework for the high-efficient degradation of acetaminophen: Role of singlet oxygen and the enhancement of redox cycle. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Chen, K.; Zhou, X.; Gong, C.; Wang, P.; Jiao, Y.; Mao, P.; Chen, K.; Lu, J.; Yang, Y. Trimetallic MOFs-derived Fe-Co-Cu oxycarbide toward peroxymonosulfate activation for efficient trichlorophenol degradation via high-valent metal-oxo species. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.M.A.; Attia, M.; Tetzlaff, D.; Apfel, U. Tailoring the Electrocatalytic Activity of Pentlandite FexNi9-XS8 Nanoparticles via Variation of the Fe: Ni Ratio for Enhanced Water Oxidation. ChemElectroChem 2021, 8, 3863–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, R.; Dhainy, J.; Halaoui, L.I. OER Catalysis at Activated and Codeposited NiFe-Oxo/Hydroxide Thin Films Is Due to Postdeposition Surface-Fe and Is Not Sustainable without Fe in Solution. ACS Catal. 2019, 10, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hou, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Song, Z.; Huang, Y. Facile and green synthesis of carbon nanopinnacles for the removal of chlortetracycline: Performance, mechanism and biotoxicity. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 133822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Du, P.; Xing, L.; Xu, W.; Ni, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Yu, G.; et al. Proton transfer triggered in-situ construction of C=N active site to activate PMS for efficient autocatalytic degradation of low-carbon fatty amine. Water Res. 2023, 240, 120119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, K.; Liu, D.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Luo, L.; Gong, G.; Han, R.; Yin, A.; Guo, L. N-doped graphene loaded with Ru sites as PMS activators for SMX degradation via non-radical pathway: Efficiency, selectivity and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; He, Z.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y. Mechanism of NH3-SCR denitration catalyzed synergistically by Fe-Ce dual active sites in bastnäsite: A DFT study on the Fe-driven radical pathway and Ce oxygen vacancy regulation. Mol. Catal. 2025, 586, 115423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, B.M.; Albadr, R.J.; Jain, V.; Kumar, A.; Ganesan, S.; Shankhyan, A.; Supriya, S.; Ray, S.; Taher, W.M.; Alwan, M.; et al. Modulating the Adsorption Properties of Benzene and Nitrobenzene Molecules on the Novel Ptn Cluster Modified C3N Nanosheets for Sensing Applications: A Comparative DFT Investigation. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 35, 6005–6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Ma, S.; Yuan, K.; Chen, D.; Zhang, W.; Ding, H.; He, Z.; Fan, T.; Xu, E.; Li, Y. Oxygen vacancy-driven synergistic photocatalytic and peroxymonosulfate activation over iron-doped titanium dioxide for ciprofloxacin degradation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Li, M.; Huo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wen, N.; He, M. Radical and non-radical pathways of organic arsenic removal in the heterogeneous peroxymonosulfate (PMS) activation system: A DFT study. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 525, 146611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tian, J.; Cui, Y.; Li, N.; Cui, X.; Yan, B.; Chen, G. Synergy of CoN3 and CuN3O2 sites in single atom-decorated biochar for peroxymonosulfate activation: Accelerating the production of SO4•− and •OH. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 154133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, H.; Wei, J.; Lu, Y.; Jing, Q.; Liang, M.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, G. Durable flame retardant containing a -C=C-P(=O)-O-C group with π–π conjugation for cotton fabrics. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 233, 111189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W. Insight into novel Fe3C/Mo2C@carbonized polyaniline activated PMS for parachlorophenol degradation: Key roles of Mo2+, C=O bonds and N-doping. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 322, 124359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Chen, B.; Xu, T.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, P.; Bao, J. Modulation of C=O groups concentration in carbon-based materials to enhance peroxymonosulfate activation towards degradation of organic contaminant: Mechanism of the non-radical oxidation pathway. Environ. Res. 2025, 275, 121442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chu, Z.; Liu, H.; Han, Z.; Chen, T.; Zou, X.; Chen, D. Comparative study of chloroquine phosphate degradation by calcite/PMS and dolomite/PMS systems. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 380, 135431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, F.; Liu, Y.; Feng, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, L.; Qi, F.; Liu, C. Carbonized polyaniline activated peroxymonosulfate (PMS) for phenol degradation: Role of PMS adsorption and singlet oxygen generation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2021, 286, 119921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamad, M. Insights into C–N Bond Formation through the Coreduction of Nitrite and CO2: Guiding Selectivity Toward C–N Bond. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 8497–8510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Gao, X.; He, B.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, T.; Yin, X. ZIFs material-derived bimetallic oxide heterojunctions activate perodisulfate to degrade chlortetracycline rapidly: The synergistic effects of oxygen vacancies and rapid electron transfer. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483, 149436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, B.; Sun, Z. Mechanism of self-supporting montmorillonite composite material for bio-enhanced degradation of chlorotetracycline: Electron transfer and microbial response. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 404, 130928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, X.; Lv, X.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, T.; Zhang, J.; Wan, J.; Zhen, Y.; Wang, T. Insight into photocatalytic chlortetracycline degradation by WO3/AgI S-scheme heterojunction: DFT calculation, degradation pathway and electron transfer mechanism. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 472, 143521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Guo, W.; Dong, H.; Meng, D.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, G.; Xin, Y.; Chen, Q. Construction of piezoelectric fenton-like system over BaTiO3/α-FeOOH for highly efficient degradation of demethylchlortetracycline. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 359, 130471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Gao, X.; Han, J.; Cao, M.; Qing, L.; Yu, L.; Zhang, X. Performance and Mechanism of Monolithic Co-Doped Nickel–Iron Foam Catalyst for Highly Efficient Activation of PMS in Degrading Chlortetracycline in Water. Catalysts 2026, 16, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010039

Yang Y, Gao X, Han J, Cao M, Qing L, Yu L, Zhang X. Performance and Mechanism of Monolithic Co-Doped Nickel–Iron Foam Catalyst for Highly Efficient Activation of PMS in Degrading Chlortetracycline in Water. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yiqiong, Xuyang Gao, Juan Han, Mingkun Cao, Li Qing, Liren Yu, and Xiaodong Zhang. 2026. "Performance and Mechanism of Monolithic Co-Doped Nickel–Iron Foam Catalyst for Highly Efficient Activation of PMS in Degrading Chlortetracycline in Water" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010039

APA StyleYang, Y., Gao, X., Han, J., Cao, M., Qing, L., Yu, L., & Zhang, X. (2026). Performance and Mechanism of Monolithic Co-Doped Nickel–Iron Foam Catalyst for Highly Efficient Activation of PMS in Degrading Chlortetracycline in Water. Catalysts, 16(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010039