In-Situ Fabrication of Double Shell WS2/TiO2 with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity Toward Organic Pollutant Degradation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

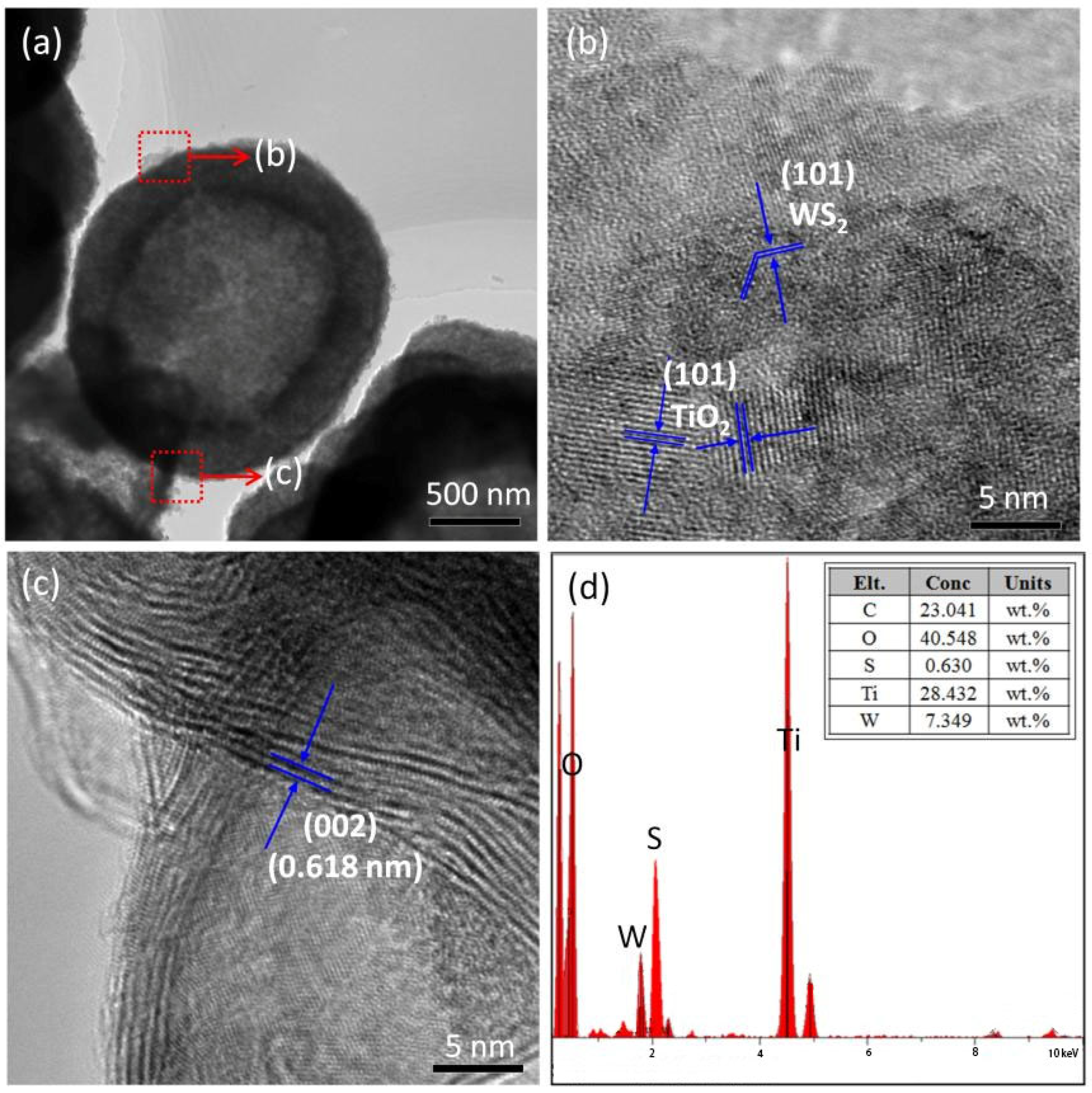

2.1. SEM and TEM Analysis

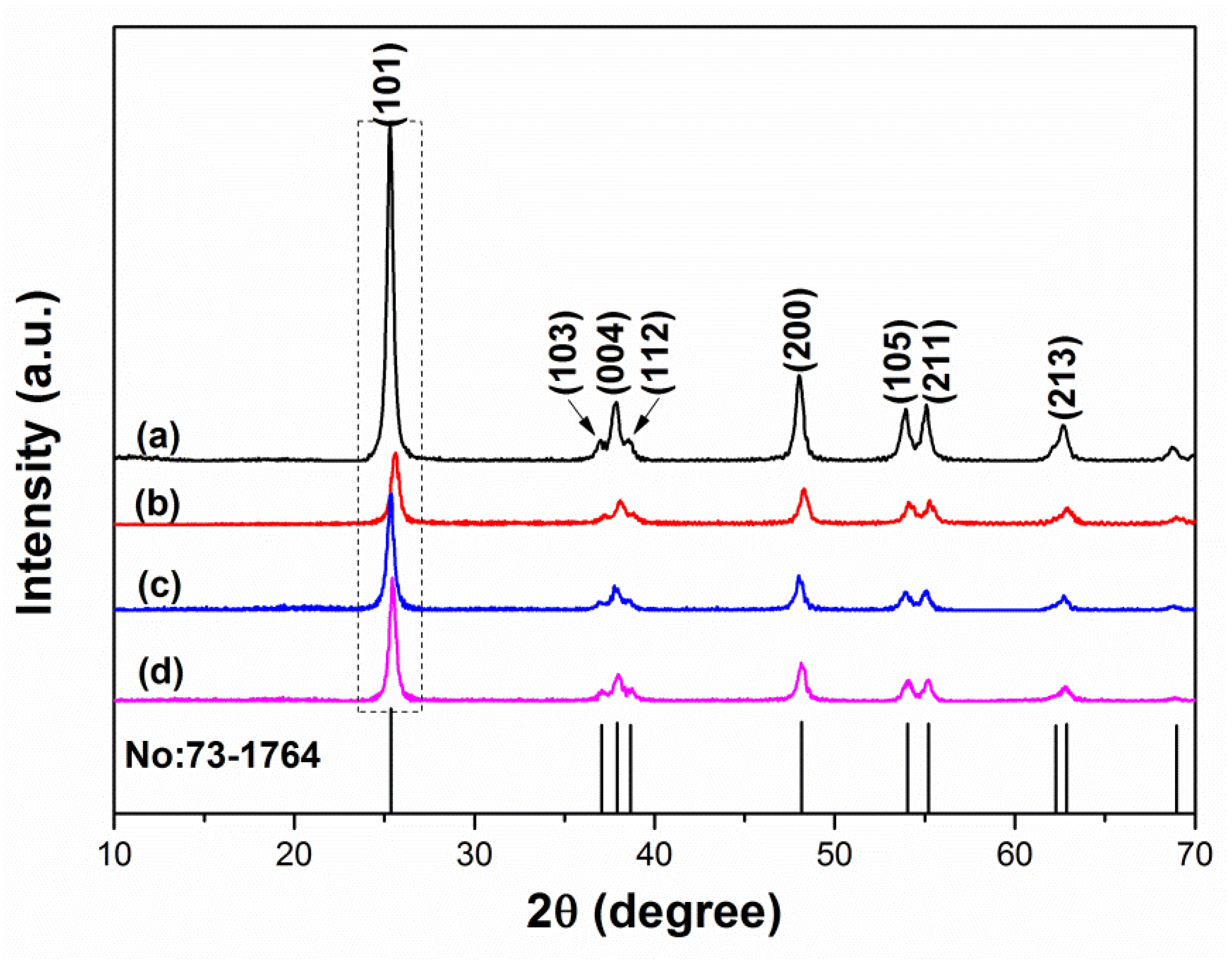

2.2. XRD Analysis

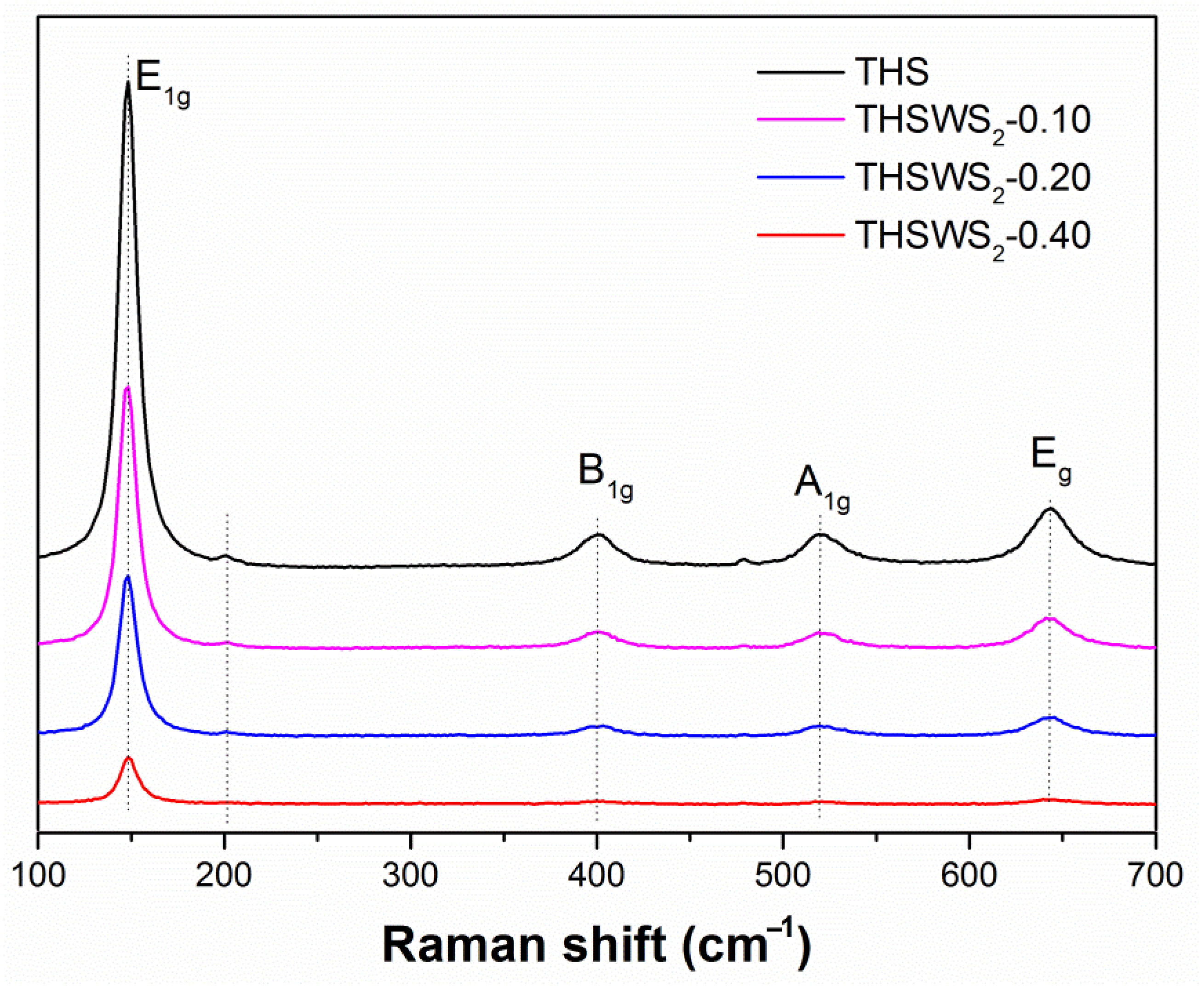

2.3. Raman Analysis

2.4. XPS Analysis

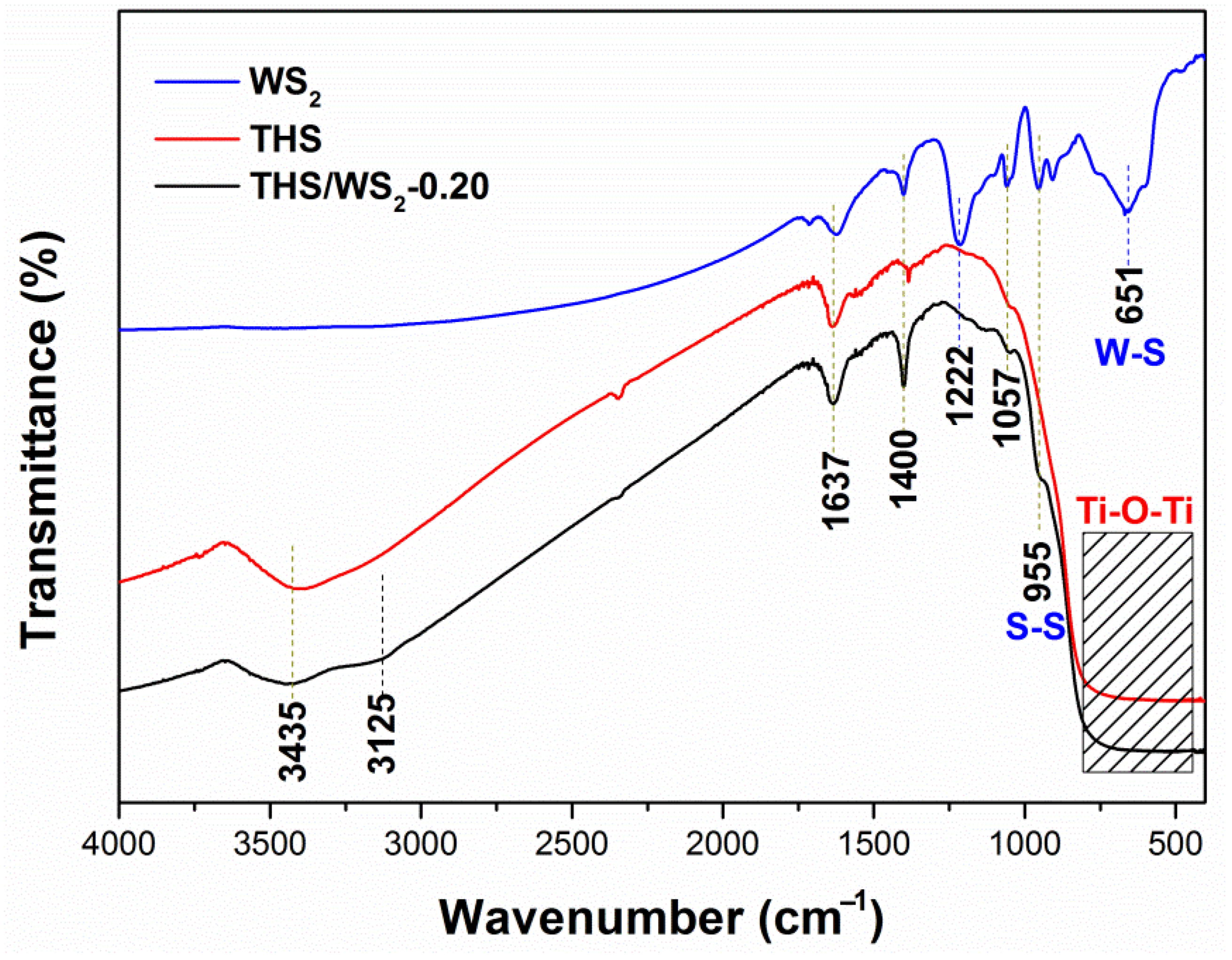

2.5. FT-IR Analysis

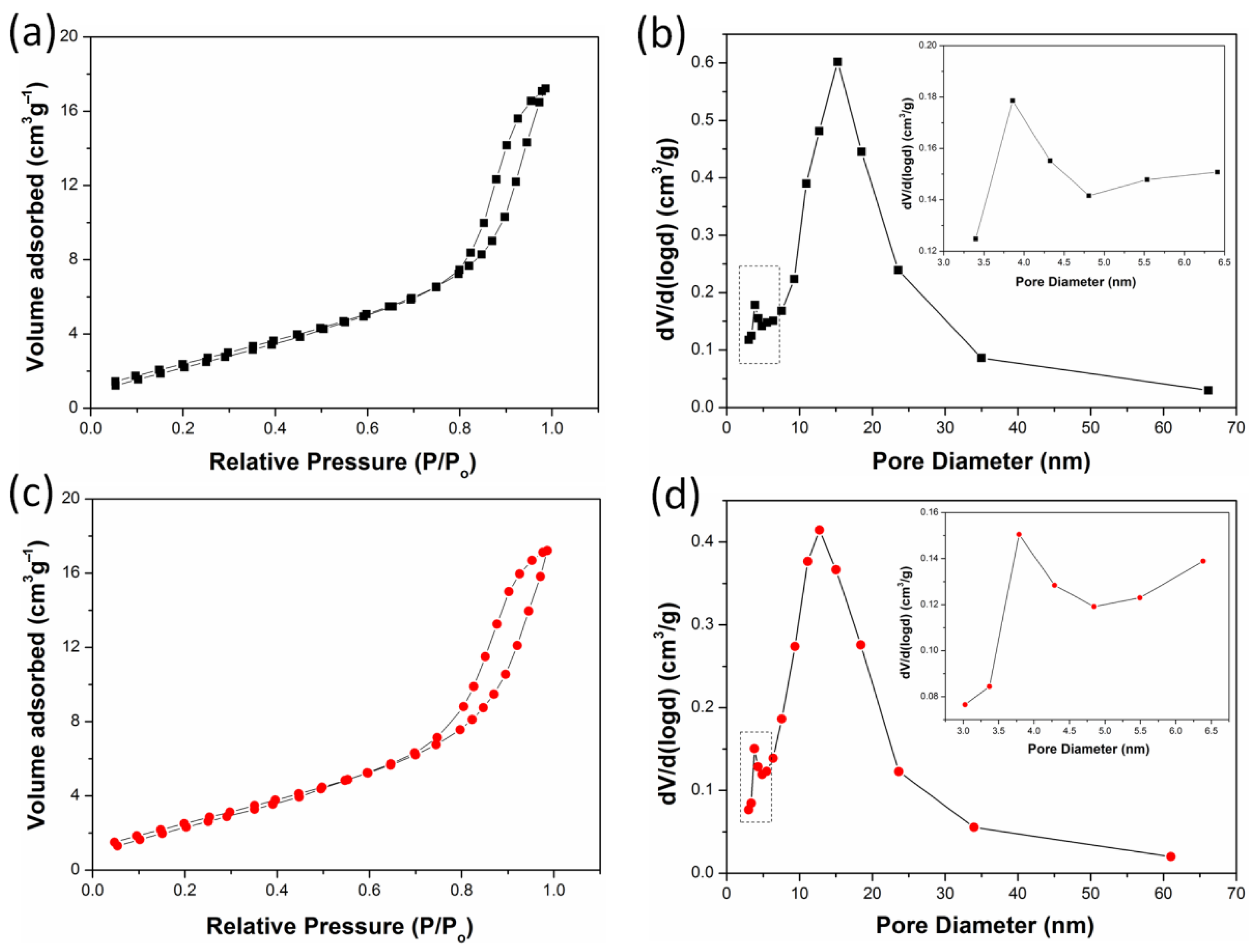

2.6. BET Analysis

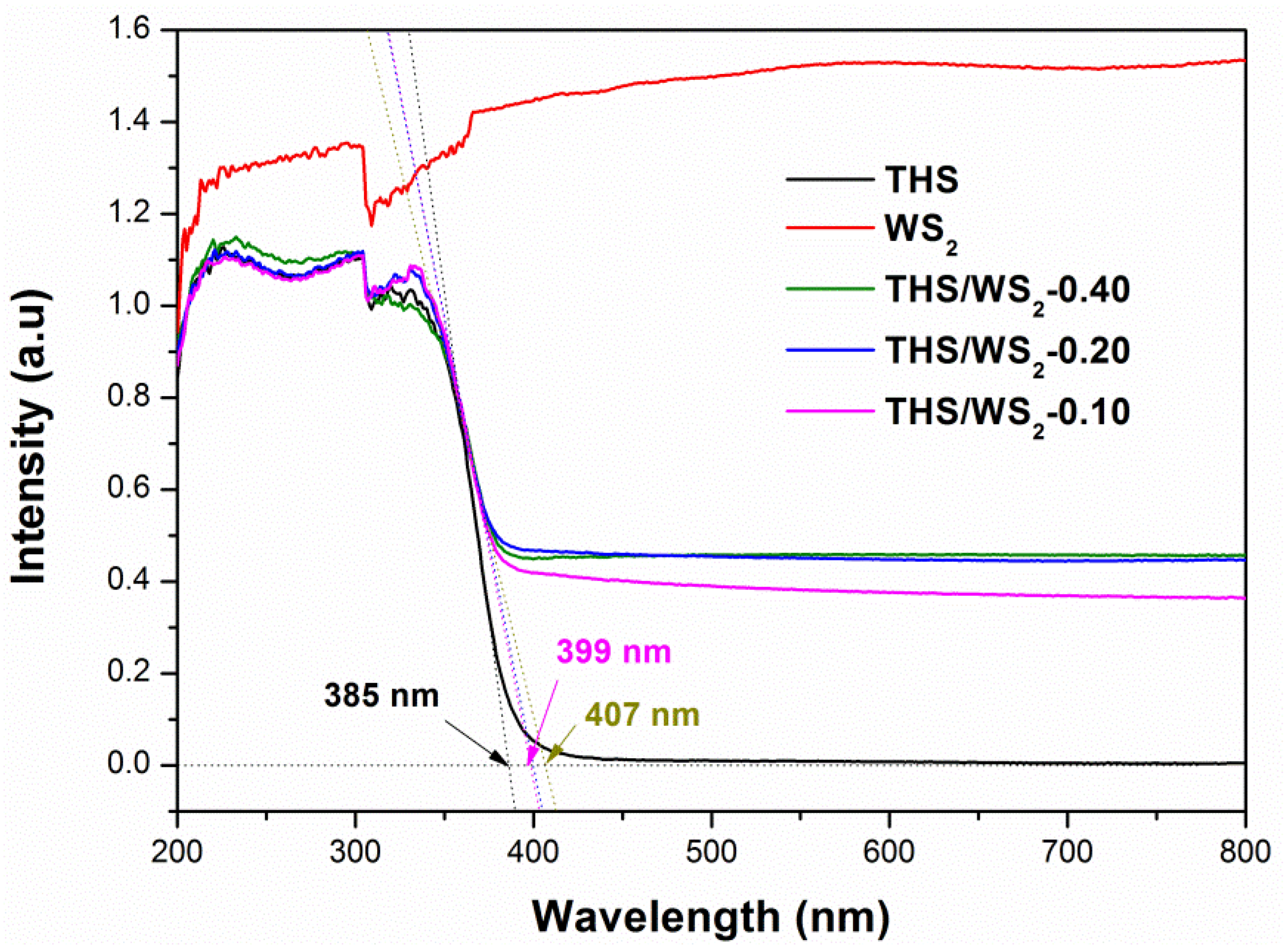

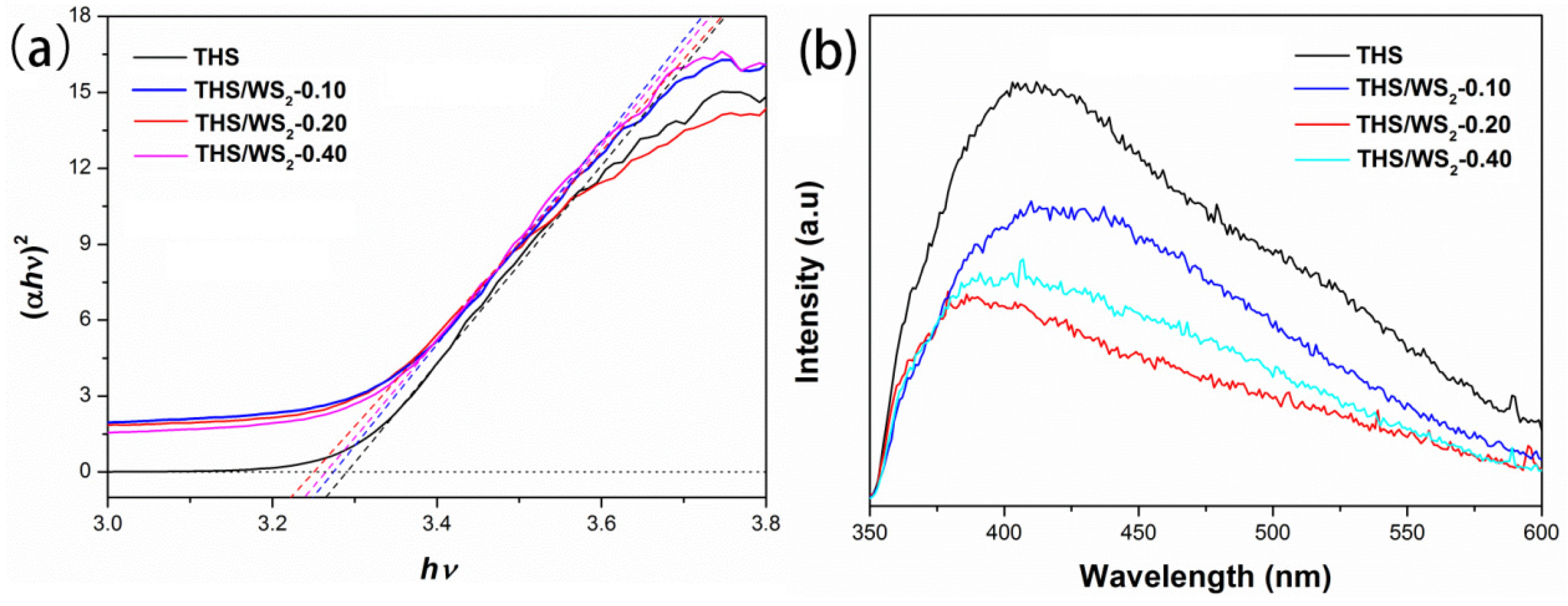

2.7. Optical Performance Analysis

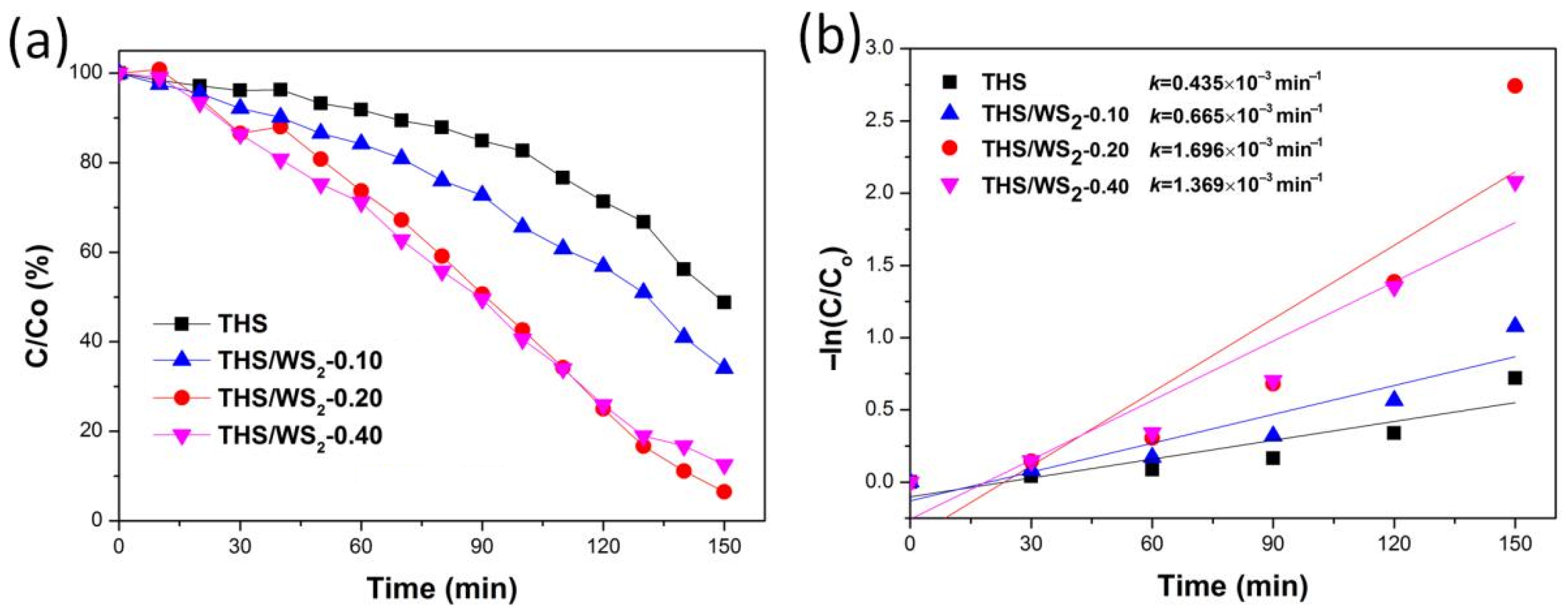

2.8. Analysis of Photocatalytic Degradation of RhB by THS/WS2

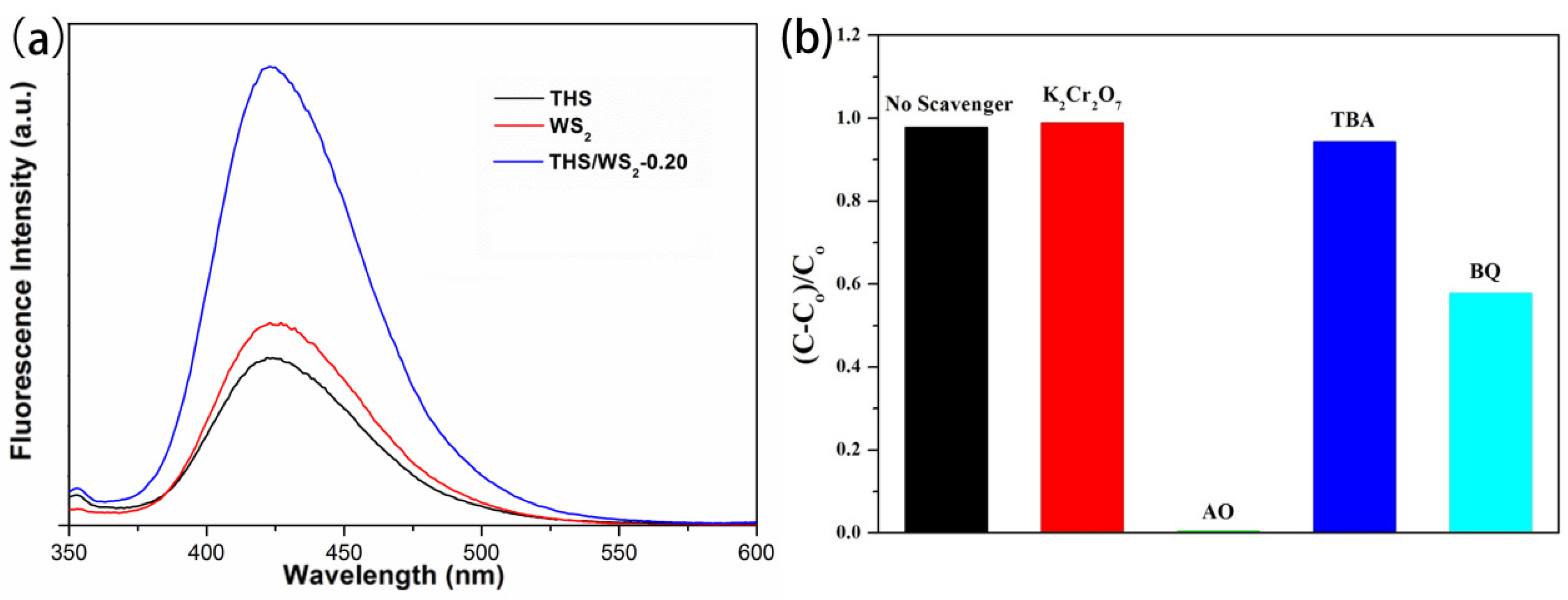

2.9. Analysis of the Mechanism of Photocatalytic Degradation of RhB by THS/WS2

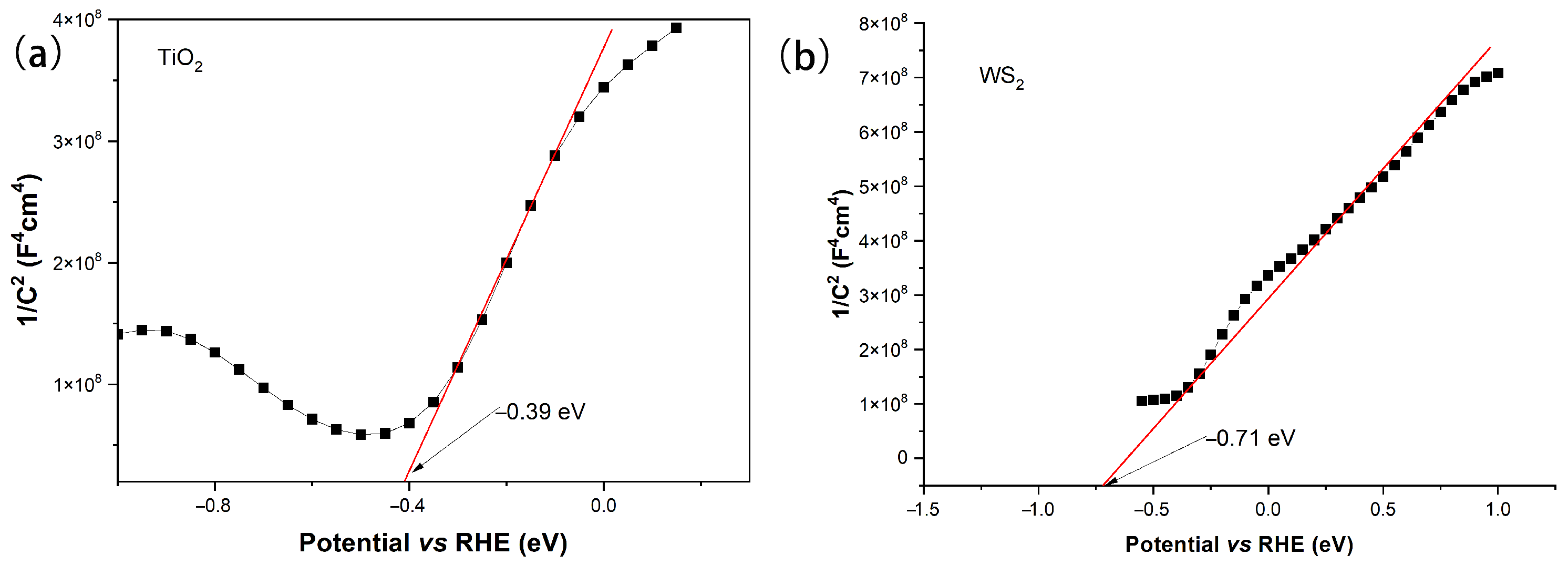

2.10. Band Structure Analysis

3. Experimental

3.1. Preparation of THS/WS2 Composites

3.1.1. Preparation of TiO2 Hollow Submicrospheres

3.1.2. Preparation of THS/WS2 Delaminated Composites

3.2. Characterization

3.3. Photoreaction Procedures

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, Y.; Choi, J.H.; Jeon, H.J.; Choi, K.M.; Lee, J.W.; Kang, J.K. Titanium-embedded layered double hydroxides as highly efficient water oxidation photocatalysts under visible light. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Sun, H.; Zhang, K.-Q.; Lai, Y. Uniform carbon dots@TiO2 nanotube arrays with full spectrum wavelength light activation for efficient dye degradation and overall water splitting. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 16046–16058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, Q.; Xie, S.; Weng, B.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y. Revealing the Double-Edged Sword Role of Graphene on Boosted Charge Transfer versus Active Site Control in TiO2 Nanotube Arrays@RGO/MoS2 Heterostructure. Small 2018, 14, 1704531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, X.; Tang, Y. Enhanced photoelectrochemical performance of MoS2 nanobelts-loaded TiO2 nanotube arrays by photo-assisted electrodeposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 425, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yu, H.; Cheng, B.; Trapalis, C. Effects of calcination temperature on the microstructures and photocatalytic activity of titanate nanotubes. J. Mol. Catal. A-Chem. 2006, 249, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Fang, P.; Wu, W.; Ding, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, C.; Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, D. Solvothermal-Assisted Synthesis for Self-Assembling TiO2 Nanorods on Large Graphitic Carbon Nitride Sheets with Their Anti-Recombination in Photocatalytic Removal of Cr (VI) and Rhodamin B Under Visible Light Irradiation. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 3231–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Mahadik, M.A.; Chung, H.S.; Ryu, J.H.; Jang, J.S. Facile Hydrothermally Synthesized a Novel CdS Nanoflower/Rutile-TiO2 Nanorod Heterojunction Photoanode Used for Photoelectrocatalytic Hydrogen Generation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 7537–7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, J.; Jin, F.; Na, P. Carbon dots-TiO2 nanosheets composites for photoreduction of Cr (VI) under sunlight illumination: Favorable role of carbon dots. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 224, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Xu, G.; Zhang, E.; Wang, H.; Kong, Z.; Xi, J.; Ji, Z. Anatase TiO2 nanosheets with coexposed {101} and {001} facets coupled with ultrathin SnS2 nanosheets as a face-to-face n-p-n dual heterojunction photocatalyst for enhancing photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 420, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, X.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, E.; Wang, H.; Kong, Z.; Xi, J.; Ji, Z. Constructing a Novel n-p-n Dual Heterojunction between Anatase TiO2 Nanosheets with Coexposed {101}, {001} Facets and Porous ZnS for Enhancing Photocatalytic Activity. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 6133–6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhao, N.; Guo, L.; He, F.; Shi, C.; He, C.; Li, J.; Liu, E. Facile synthesis of 3D few-layered MoS2 coated TiO2 nanosheet core-shell nanostructures for stable and high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 12895–12905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, G.; Duan, H. Uniform Gold-Nanoparticle-Decorated {001}-Faceted Anatase TiO2 Nanosheets for Enhanced Solar-Light Photocatalytic Reactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2017, 9, 36907–36916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, L.; Bi, J.; Liang, S.; Liu, M. Design and Synthesis of TiO2 Hollow Spheres with Spatially Separated Dual Cocatalysts for Efficient Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wei, B.; Xu, L.; Gao, H.; Sun, W.; Che, J. Multilayered MoS2 coated TiO2 hollow spheres for efficient photodegradation of phenol under visible light irradiation. Mater. Lett. 2016, 179, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; He, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, D. Template-free solvothermal synthesis and photocatalytic properties of TiO2 hollow spheres. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 4068–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K. Facile in-situ Solvothermal Method to synthesize double shell ZnIn2S4 nanosheets/TiO2 hollow nanosphere with enhanced photocatalytic activities. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 6115–6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Zeng, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, X.; Yu, H. MoS2 nanosheets encapsulating TiO2 hollow spheres with enhanced photocatalytic activity for nitrophenol reduction. Mater. Lett. 2017, 209, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Liu, P.; Zheng, Z.; Weng, S.; Huang, J. Morphology engineering of V2O5/TiO2 nanocomposites with enhanced visible light-driven photofunctions for arsenic removal. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2016, 184, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Yin, D.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Mu, J. One-pot template-free preparation of mesoporous TiO2 hollow spheres and their photocatalytic activity. Mater. Res. Bull. 2012, 47, 3065–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Yu, W.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, H.; Tang, C.; Sun, K.; Wu, X.; Dong, L.; Chen, Y. Efficient fabrication and photocatalytic properties of TiO2 hollow spheres. Catal. Commun. 2009, 10, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Jiao, X.; Chen, D. Template-free fabrication of TiO2 hollow spheres and their photocatalytic properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, W.; Liu, S. Controlled fabrication of nanosized TiO2 hollow sphere particles via acid catalytic hydrolysishydrothermal treatment. Powder Technol. 2011, 212, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalfani, M.; Hu, Z.; Yu, W.-B.; Mahdouani, M.; Bourguiga, R.; Wu, M.; Li, Y.; Van Tendeloo, G.; Djaoued, Y.; Su, B.-L. BiVO4/3DOM TiO2 nanocomposites: Effect of BiVO4 as highly efficient visible light sensitizer for highly improved visible light photocatalytic activity in the degradation of dye pollutants. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2017, 205, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamdab, U.; Wetchakun, K.; Phanichphant, S.; Kangwansupamonkon, W.; Wetchakun, N. InVO4-BiVO4 composite films with enhanced visible light performance for photodegradation of methylene blue. Catal. Today 2016, 278, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jin, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Dong, S.; Sun, J.; Sun, J. Facile fabrication of novel BiVO4/Bi2S3/MoS2 n-p heterojunction with enhanced photocatalytic activities towards pollutant degradation under natural sunlight. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 505, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Guo, Z.; Wang, H.; Deng, Y.; Niu, C.; et al. Novel ternary heterojunction photcocatalyst of Ag nanoparticles and g-C3N4 nanosheets co-modified BiVO4 for wider spectrum visible-light photocatalytic degradation of refractory pollutant. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2017, 205, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Ge, L.; Han, C.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, S.; Xu, H. Novel AuPd bimetallic alloy decorated 2D BiVO4 nanosheets with enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2017, 204, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Yu, W.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, E.; Wang, H.; Kong, Z.; Xi, J.; Ji, Z. Novel dual heterojunction between MoS2 and anatase TiO2 with coexposed {101} and {001} facets. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 5274–5285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Sinhamahapatra, A.; Kang, T.H.; Ghosh, S.C.; Yu, J.S.; Panda, A.B. Hydrogenated MoS2 QD-TiO2 heterojunction mediated efficient solar hydrogen production. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 17029–17036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Sang, Y.; Jiang, H.; He, J.; Xu, L.; Liu, H. Few-layered MoS2 nanosheets wrapped ultrafine TiO2 nanobelts with enhanced photocatalytic property. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 6101–6109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Fan, Z.; Ding, S.; Yu, D.; Du, Y. Fabrication of MoS2 nanosheet@TiO2 nanotube hybrid nanostructures for lithium storage. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 5245–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zhao, H.; Tian, J.; Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Cui, H. Synthesis of few-layer MoS2 nanosheets-coated TiO2 nanosheets on graphite fibers for enhanced photocatalytic properties. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 172, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Wang, R.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Jia, H. MoS2-hybridized TiO2 nanosheets with exposed {001} facets to enhance the visible-light photocatalytic activity. Mater. Lett. 2015, 160, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Lu, Z.; Jin, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, G.; Zhang, E.; Wang, H.; Kong, Z.; Xi, J.; et al. Crystal face regulating MoS2/TiO2(001) heterostructure for high photocatalytic activity. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 688, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J.-T.; Cai, X.-J.; Na, P. Hydrothermal fabrication of hyacinth flower-like WS2 nanorods and their photocatalytic properties. Mater. Lett. 2017, 189, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorai, A.; Bayan, S.; Gogurla, N.; Midya, A.; Ray, S.K. Highly Luminescent WS2 Quantum Dots/ZnO Heterojunctions for Light Emitting Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2016, 9, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, A.; Saievar-Iranizad, E. Synthesis of blue photoluminescent WS2 quantum dots via ultrasonic cavitation. J. Lumin. 2017, 185, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, A.; Selig, M.; Berghauser, G.; Yu, J.; Hill, H.M.; Rigosi, A.F.; Brus, L.E.; Knorr, A.; Heinz, T.F.; Malic, E.; et al. Enhancement of exciton-phonon scattering from monolayer to bilayer WS2. Nano Lett. 2018, 8, 6135–6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukowski, M.A.; Daniel, A.S.; English, C.R.; Meng, F.; Forticaux, A.; Hamers, R.J.; Jin, S. Highly active hydrogen evolution catalysis from metallic WS2 nanosheets. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wan, J.; Yang, Z.; Hu, Z. Preparation of the MoS2/TiO2/HMFs ternary composite hollow microfibres with enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 502, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sabban, H.; Mady, A.; Diab, M.A.; Al Zoubi, W.; Kang, J.H.; Ko, Y.G. Novel environmentally-friendly 0D/3D TiO2@FeMoO4 binary composite with boosted photocatalytic performance: Structural analysis and Z-scheme interpretations. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 100, 177265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; Na, P. Construction of 2D-2D TiO2 nanosheet/layered WS2 heterojunctions with enhanced visible-light-responsive photocatalytic activity. Chin. J. Catal. 2019, 40, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borik, M.A.; Diab, M.; El-Sabban, H.A.; El-Adasy, A.-B.A.; El-Gaby, M.S. Designed construction of boosted visible-light Z-scheme TiO2/PANI/Cu2O heterojunction with elaborated photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes. Synth. Met. 2024, 306, 117642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Voiry, D.; Ahn, S.J.; Kang, D.; Kim, A.Y.; Chhowalla, M.; Shin, H.S. Two-Dimensional Hybrid Nanosheets of Tungsten Disulfide and Reduced Graphene Oxide as Catalysts for Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 13751–13754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eftekhari, A. Tungsten dichalcogenides (WS2, WSe2, and WTe2): Materials chemistry and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 18299–18325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Manthiram, A. Template-free TiO2 hollow submicrospheres embedded with SnO2 nanobeans as a versatile scattering layer for dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 2848–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Samples | Diffraction Peak Intensity of Plane (101) |

|---|---|

| THS | 1846.32 |

| THS/WS2-0.10 | 1270.12 |

| THS/WS2-0.20 | 1267.29 |

| THS/WS2-0.40 | 765.62 |

| Samples | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Diameter (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||

| THS | 99.6 | 0.28 | 3.05 | 15.10 |

| THS/WS2-0.20 | 76.1 | 0.21 | 3.04 | 12.65 |

| Samples | n (Na2WO4·2H2O) /mmol | n (TiO2) /mmol | W/Ti Moral Ratio | Weight /mg | W wt% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THS/WS2-0.40 | 2.5 | 6.25 | 0.40 | 572.82 | 15.71 |

| THS/WS2-0.20 | 2.5 | 12.50 | 0.20 | 1058.64 | 5.54 |

| THS/WS2-0.10 | 2.5 | 25.00 | 0.10 | 2045.03 | 2.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Ma, J. In-Situ Fabrication of Double Shell WS2/TiO2 with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity Toward Organic Pollutant Degradation. Catalysts 2026, 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010025

Zhao J, Zhang J, Li X, Wu Y, Ma J. In-Situ Fabrication of Double Shell WS2/TiO2 with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity Toward Organic Pollutant Degradation. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Jingyu, Jinghui Zhang, Xin Li, Yongchuan Wu, and Jing Ma. 2026. "In-Situ Fabrication of Double Shell WS2/TiO2 with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity Toward Organic Pollutant Degradation" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010025

APA StyleZhao, J., Zhang, J., Li, X., Wu, Y., & Ma, J. (2026). In-Situ Fabrication of Double Shell WS2/TiO2 with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity Toward Organic Pollutant Degradation. Catalysts, 16(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010025