Improving the Efficiency of Hydrogen Spillover by an Alkali Treatment Strategy for Boosting Formic Acid Dehydrogenation Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- HCOOH → H2+ CO2, ∆G = −48.4 kJ·mol−1

- (2)

- HCOOH → H2O+ CO, ∆G = −28.5 kJ·mol−1

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of CN and CNK−X

2.2. Catalytic Activity and Stability of Pd/CN and Pd/CNK−X

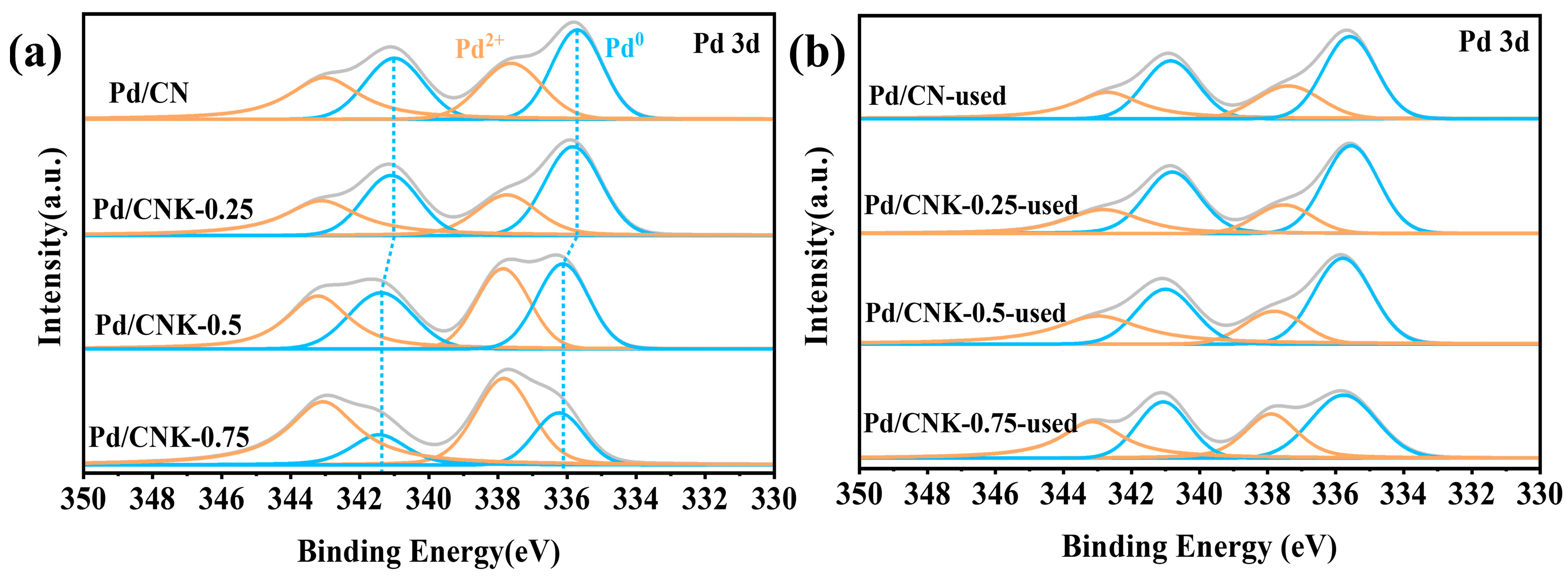

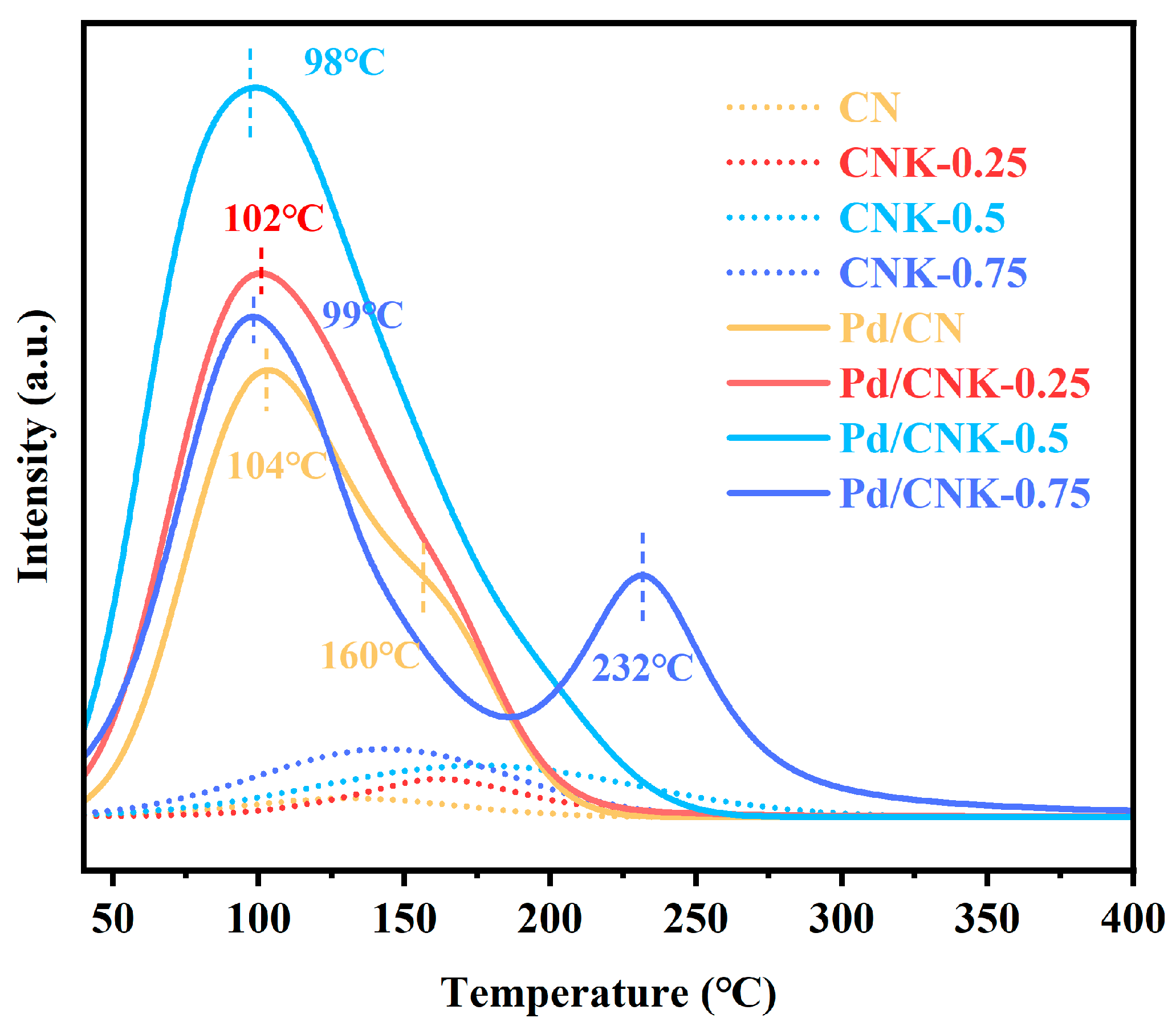

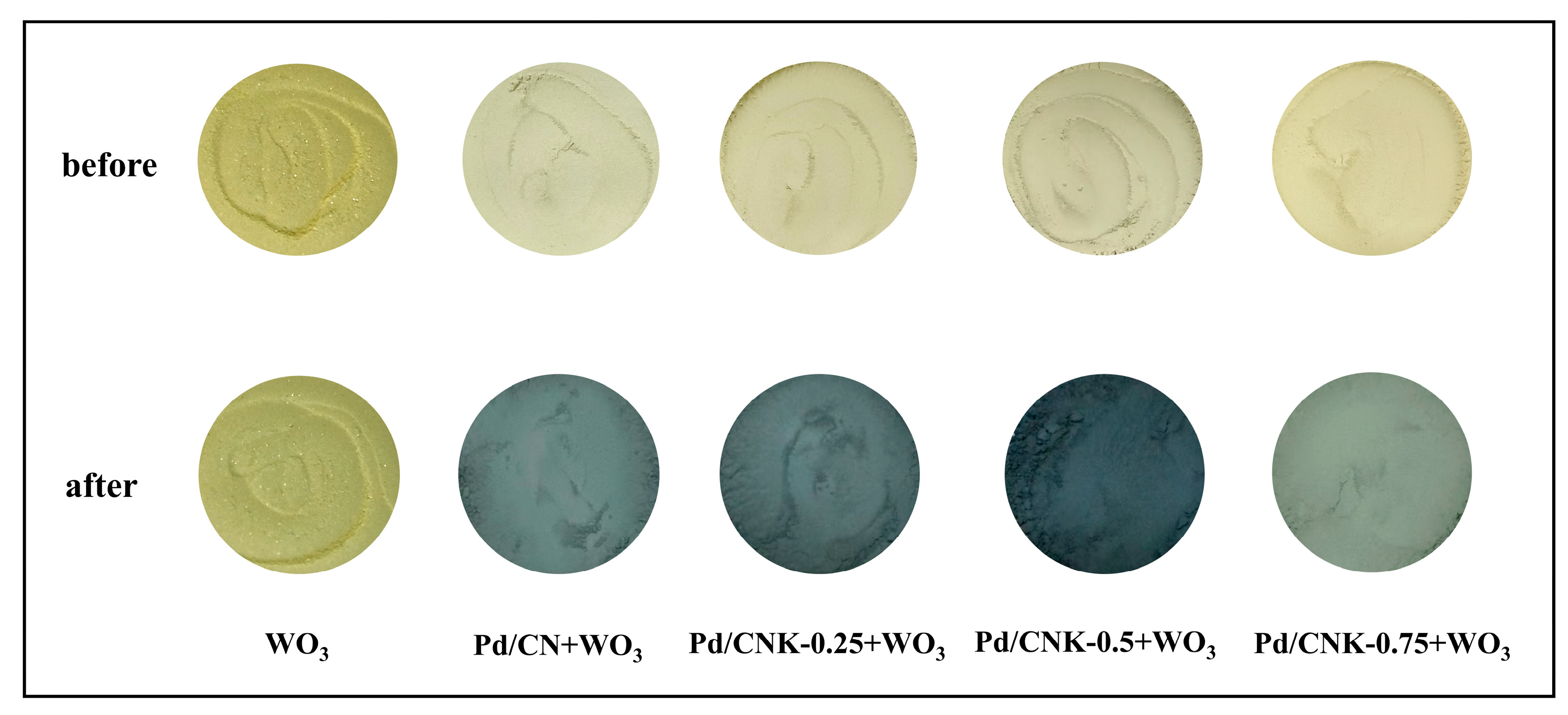

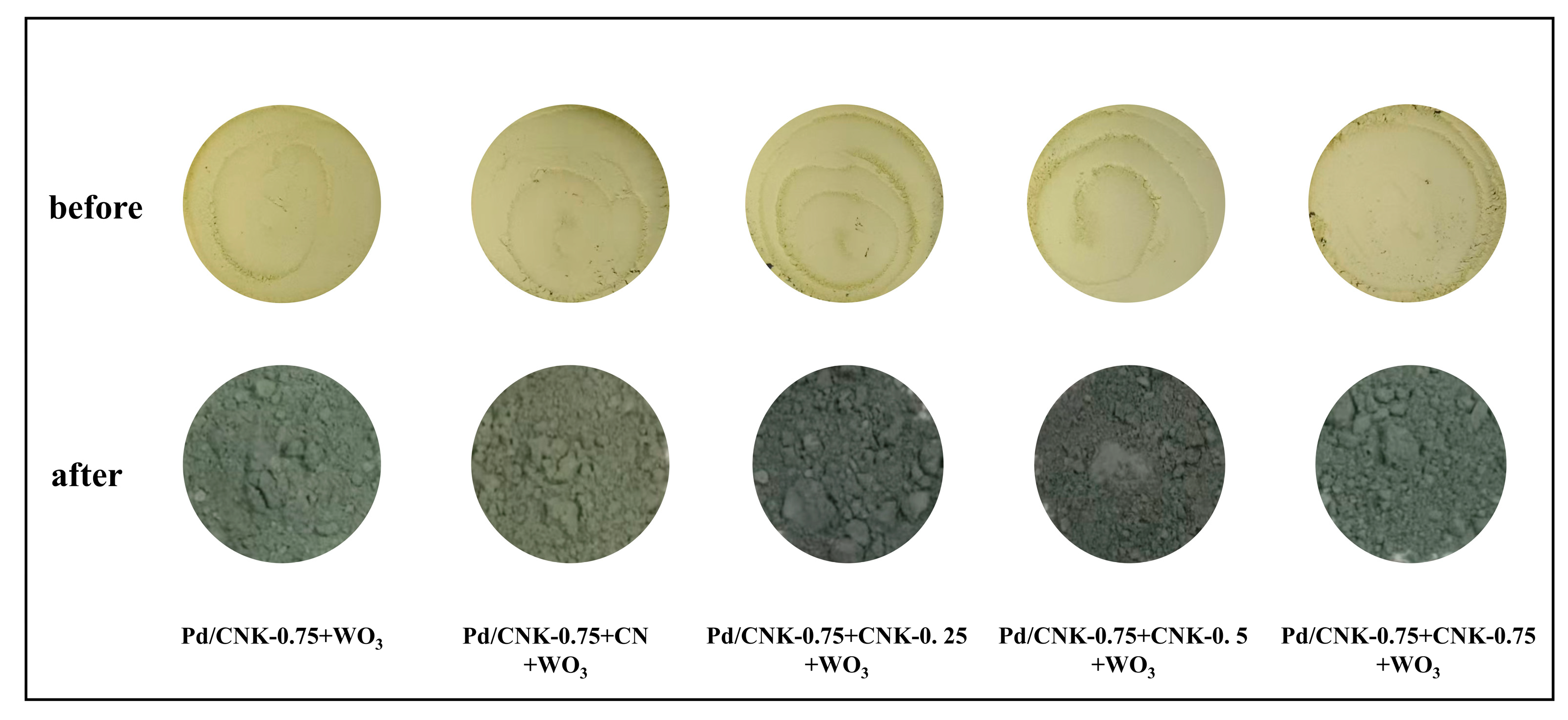

2.3. Characterization of the Catalysts

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Synthesis of Graphite Carbon Nitride (CN) and Potassium Hydroxide−Treated CN (CNK−X)

3.3. Synthesis of Pd/CN and Pd/CNK−X

3.4. Characterization of Catalysts and Supports

3.5. Catalytic Activity Test

3.6. Durability Tests of the Catalysts

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alconada, K.; Barrio, V.L. Evaluation of bimetallic Pt−Co and Pt−Ni catalysts in LOHC dehydrogenation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Iguchi, M.; Chatterjee, M.; Himeda, Y.; Xu, Q.; Kawanami, H. Formic Acid-Based Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carrier System with Heterogeneous Catalysts. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2018, 2, 1700161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Saqib, A.; Lean, H.H. Economic policy uncertainty and green energy in BRICS: Impacts on sustainability. Energy 2025, 317, 134717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsby, D.; Price, J.; Pye, S.; Ekins, P. Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 degrees C world. Nature 2021, 597, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, B.; Zendehboudi, S.; Monajati Saharkhiz, M.H.; Afrouzi, Z.A.; Mohammadzadeh, O.; Elkamel, A. Multi-objective Optimization of a Novel Hybrid Structure for Co-generation of Ammonium Bicarbonate, Formic Acid, and Methanol with Net-Zero Carbon Emissions. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 12474–12502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paragian, K.; Li, B.; Massino, M.; Rangarajan, S. A computational workflow to discover novel liquid organic hydrogen carriers and their dehydrogenation routes. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2020, 5, 1658–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.X.; Li, X.G.; Yao, Q.L.; Lu, Z.H.; Zhang, N.; Xia, J.; Yang, K.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zhang, K.; Liu, H.Z.; et al. 2022 roadmap on hydrogen energy from production to utilizations. Rare Met. 2022, 41, 3251–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modisha, P.M.; Ouma, C.N.M.; Garidzirai, R.; Wasserscheid, P.; Bessarabov, D. The Prospect of Hydrogen Storage Using Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 2778–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, Y.; Higo, T. Recent Trends on the Dehydrogenation Catalysis of Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carrier (LOHC): A Review. Top. Catal. 2021, 64, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Quintanilla, A.; Vega, G.; Casas, J.A. Formic acid-to-hydrogen on Pd/AC catalysts: Kinetic study with catalytic deactivation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 317, 121802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; He, P.; Wu, J.; Chen, N.; Pan, C.; Shi, E.; Jia, H.; Hu, T.; He, K.; Cai, Q.; et al. Reviews on Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysts for Dehydrogenation and Recycling of Formic Acid: Progress and Perspectives. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 17075–17093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, I.; Chatterjee, S.; Cheng, H.; Parsapur, R.K.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Ye, E.; Kawanami, H.; Low, J.S.C.; Lai, Z.; et al. Formic Acid to Power towards Low-Carbon Economy. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, J.-Y. Computational study on graphdiyne supported PdxCuy clusters as potential catalysts for formic acid dehydrogenation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 79, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, S.; Mori, K.; Futamura, Y.; Yamashita, H. PdAg Nanoparticles Supported on Functionalized Mesoporous Carbon: Promotional Effect of Surface Amine Groups in Reversible Hydrogen Delivery/Storage Mediated by Formic Acid/CO2. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2277–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Obata, K.; Yui, Y.; Honma, T.; Lu, X.; Ibe, M.; Takanabe, K. Potential-Rate Correlations of Supported Palladium-Based Catalysts for Aqueous Formic Acid Dehydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 9191–9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, Q.; Gao, L.; Jin, Z.; Ge, J.; Liu, C.; Xing, W. Recent progress in hydrogen production from formic acid decomposition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 7055–7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Jiao, Y.; Li, X.; Lin, T.; Yang, C.; Chen, S.; Chen, Z.; Qi, H.; Bartling, S.; Jiao, H.; et al. CO−Tolerant Heterogeneous Ruthenium Catalysts for Efficient Formic Acid Dehydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202416530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, D.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Lei, G. Recent progress on heterogeneous catalytic formic acid decomposition for hydrogen production. Fuel 2025, 383, 133824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Jia, A.; Song, J.; Cao, S.; Wang, N.; Liu, X. Metal-support interactions in heterogeneous catalytic hydrogen production of formic acid. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, R.S. The decomposition of formic acid catalysed by soluble metal complexes. Chem. Commun. 1967, 18, 923b–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordakis, K.; Tang, C.; Vogt, L.K.; Junge, H.; Dyson, P.J.; Beller, M.; Laurenczy, G. Homogeneous Catalysis for Sustainable Hydrogen Storage in Formic Acid and Alcohols. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 372–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellmann, D.; Sponholz, P.; Junge, H.; Beller, M. Formic acid as a hydrogen storage material-development of homogeneous catalysts for selective hydrogen release. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 3954–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Geng, S.; Du, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, F.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Efficient direct formic acid electrocatalysis enabled by rare earth-doped platinum-tellurium heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grad, O.; Mihet, M.; Dan, M.; Blanita, G.; Radu, T.; Berghian-Grosan, C.; Lazar, M.D. Au/reduced graphene oxide composites: Eco-friendly preparation method and catalytic applications for formic acid dehydrogenation. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 6991–7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Lu, Z.H.; Jiang, H.L.; Akita, T.; Xu, Q. Synergistic catalysis of metal-organic framework-immobilized Au−Pd nanoparticles in dehydrogenation of formic acid for chemical hydrogen storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11822–11825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, G.; Wang, T.; Yang, J.Y.; Herrendorf, T.; Schwiderowski, P.; Schulwitz, J.; Chen, P.; Kleist, W.; Zhao, G.; et al. Efficient Atomically Dispersed Co/N−C Catalysts for Formic Acid Dehydrogenation and Transfer Hydrodeoxygenation of Vanillin. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202300871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navlani-García, M.; Salinas-Torres, D.; Vázquez-Álvarez, F.D.; Cazorla-Amorós, D. Formic acid dehydrogenation attained by Pd nanoparticles-based catalysts supported on MWCNT−C3N4 composites. Catal. Today 2022, 397–399, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Chen, B.W.J.; Wang, N.; He, Q.; Chang, A.; Yang, C.M.; Asakura, H.; Tanaka, T.; Hulsey, M.J.; Wang, C.H.; et al. Zeolite-Encaged Pd−Mn Nanocatalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation and Formic Acid Dehydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 20183–20191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Dojo, M.; Yamashita, H. Pd and Pd−Ag Nanoparticles within a Macroreticular Basic Resin: An Efficient Catalyst for Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid Decomposition. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Bai, X.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.-N.; Wang, T.-J.; Sun, H.-Y.; Li, F.-M.; Chen, P.; Jin, P.; Yin, S.-B.; et al. Au core−PtAu alloy shell nanowires for formic acid electrolysis. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 65, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Huang, Y.; Xing, W.; Liu, C.; Liao, J.; Lu, T. High-quality hydrogen from the catalyzed decomposition of formic acid by Pd−Au/C and Pd−Ag/C. Chem. Commun. 2008, 30, 3540–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Li, H.; Xie, S.; Li, K.; Jiang, T.; Ma, X.-Y.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Terasaki, O.; Wu, Z.; et al. Mechanistic Analysis-Guided Pd−Based Catalysts for Efficient Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid Dehydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 3921–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zhao, X.; Luo, W.; Wang, Y.; Fan, G. Air-mediated construction of O, N−rich carbon: An efficient support of palladium nanoparticles toward catalytic formic acid dehydrogenation and 4-nitrophenol reduction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 29034–29045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chi, Y.; Gao, D.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, J.; Wu, C.; et al. Enhancing formic acid dehydrogenation for hydrogen production with the metal/organic interface. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 255, 117776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Tsumori, N.; Liu, Z.; Himeda, Y.; Autrey, T.; Xu, Q. Tandem Nitrogen Functionalization of Porous Carbon: Toward Immobilizing Highly Active Palladium Nanoclusters for Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 2720–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Sun, X.; Peng, W.-F.; Zhang, L.; Meng, S.; Yao, Q.; Feng, G.; Lu, Z.-H. Fast and Durable Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid over Pd−Cr(OH)3 Nanoclusters Immobilized on Amino-Modified Reduced Graphene Oxide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 6963–6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, T.W.; Ma, X.Y.; Jiang, K.; Yang, B.; Chen, S.; Cai, W.B. Disentangling heterogeneous thermocatalytic formic acid dehydrogenation from an electrochemical perspective. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, P.; Huang, Y.; Luo, X.; Liang, Z. Amine-functionalized sepiolite: Toward highly efficient palladium nanocatalyst for dehydrogenation of additive-free formic acid. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 16707–16717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Singh, A.K.; Tsumori, N.; Xu, Q. Palladium silica nanosphere-catalyzed decomposition of formic acid for chemical hydrogen storage. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 19146–19150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.; Hu, J.; Zhang, R.; Feng, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, C.; Wang, X. Efficient hydrogen production from formic acid dehydrogenation over ultrasmall PdIr nanoparticles on amine-functionalized yolk-shell mesoporous silica. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2025, 678, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Yan, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. Mechanistic insight into efficient H2 generation upon HCOONa hydrolysis. iScience 2023, 26, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yang, Q.; Nie, W.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Z.H. Anchoring IrPdAu Nanoparticles on NH2−SBA−15 for Fast Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid at Room Temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 8082–8090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Maeda, K.; Thomas, A.; Takanabe, K.; Xin, G.; Carlsson, J.M.; Domen, K.; Antonietti, M. A metal-free polymeric photocatalyst for hydrogen production from water under visible light. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudiño, L.; Rodriguez, J.J.; Belver, C.; Bedia, J. Effect of precursor on the solar photocatalytic production of hydrogen using C3N4. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 365, 132686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, J.; Fan, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Zheng, J.; Wu, M.; et al. Remedying Defects in Carbon Nitride To Improve both Photooxidation and H2 Generation Efficiencies. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3365–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Q.; Kanhere, P.; Ng, C.F.; Chen, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Huan, A.C.H.; Sum, T.C.; Ahuja, R.; Chen, Z. Defect Engineered g−C3N4 for Efficient Visible Light Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 4930–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ouyang, S.; Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, J. Constructing Solid-Gas-Interfacial Fenton Reaction over Alkalinized−C3N4 Photocatalyst To Achieve Apparent Quantum Yield of 49% at 420 nm. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13289–13297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, K.; Pan, X.; Wang, W.; Ma, J.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Shen, H.; Huang, Z.; Liu, H. In Situ Growth of Pd Nanosheets on g−C3N4 Nanosheets with Well-Contacted Interface and Enhanced Catalytic Performance for 4−Nitrophenol Reduction. Small 2018, 44, e1801812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcì, G.; García-López, E.I.; Pomilla, F.R.; Palmisano, L.; Zaffora, A.; Santamaria, M.; Krivtsov, I.; Ilkaeva, M.; Barbieriková, Z.; Brezová, V. Photoelectrochemical and EPR features of polymeric C3N4 and O−modified C3N4 employed for selective photocatalytic oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes. Catal. Today 2019, 328, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Sun, M.; Cao, X.; Wang, H.; Xia, L.; Jiang, W.; Huang, M.; He, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y. Progress in preparation, identification and photocatalytic application of defective g−C3N4. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 510, 215849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Jiao, Y.; Qin, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Boron doped C3N4 nanodots/nonmetal element (S, P, F, Br) doped C3N4 nanosheets heterojunction with synergistic effect to boost the photocatalytic hydrogen production performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 541, 148558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ren, Z.; He, Z.; Ouyang, P.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lv, K.; Dong, F. Crystallinity-defect matching relationship of g−C3N4: Experimental and theoretical perspectives. Green. Energy Environ. 2024, 9, 623–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Q.Y.; Lin, J.D.; Liu, Y.M.; He, H.Y.; Huang, F.Q.; Cao, Y. Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid at Room Temperature: Boosting Palladium Nanoparticle Efficiency by Coupling with Pyridinic-Nitrogen-Doped Carbon. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 11849–11853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.F.; Xin, J.J.; Ma, S.K.; Cui, F.J.; Zhao, Z.L.; Jia, L.H. Hydrogen Production from the Decomposition of Formic Acid over Carbon Nitride-Supported AgPd Alloy Nanoparticles. Energy Technol. 2018, 6, 2374–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, M.; Shi, T.; Cui, W.; Zhang, X.; Dong, F.; Cheng, J.; Fan, J.; Lv, K. Carbon vacancy in C3N4 nanotube: Electronic structure, photocatalysis mechanism and highly enhanced activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 262, 118281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, Q. Sodium doped flaky carbon nitride with nitrogen defects for enhanced photoreduction carbon dioxide activity. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2021, 603, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Gao, D.; Liu, Y.; Fan, J.; Yu, H. Cyano group-enriched crystalline graphitic carbon nitride photocatalyst: Ethyl acetate-induced improved ordered structure and efficient hydrogen-evolution activity. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2022, 608, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.A.; Overbury, S.H.; Dudney, N.J.; Li, M.; Veith, G.M. Gold Nanoparticles Supported on Carbon Nitride: Influence of Surface Hydroxyls on Low Temperature Carbon Monoxide Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, V.W.; Moudrakovski, I.; Botari, T.; Weinberger, S.; Mesch, M.B.; Duppel, V.; Senker, J.; Blum, V.; Lotsch, B.V. Rational design of carbon nitride photocatalysts by identification of cyanamide defects as catalytically relevant sites. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, L.; Xu, Y.; Xie, M.; Li, Z.; Wu, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhong, N.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Yan, Y.; et al. Cyano-Rich g−C3N4 in Photochemistry: Design, Applications, and Prospects. Small 2024, 20, e2304404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, C.; Qu, L. A Graphitic−C3N4 “Seaweed” Architecture for Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 11433–11437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, L.; Hu, Z.; Yu, J.C. EDTA-enhanced photocatalytic oxygen reduction on K−doped g−C3N4 with N−vacancies for efficient non-sacrificial H2O2 synthesis. J. Catal. 2023, 418, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, P.; Wang, C.; Gan, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Zhou, X.; et al. Unraveling the dual defect sites in graphite carbon nitride for ultra-high photocatalytic H2O2 evolution. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Sun, C.; Zhao, H. Potassium-Ion-Assisted Regeneration of Active Cyano Groups in Carbon Nitride Nanoribbons: Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 16644–16650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ren, M.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Y. Controllable Approach to Carbon-Deficient and Oxygen-Doped Graphitic Carbon Nitride: Robust Photocatalyst Against Recalcitrant Organic Pollutants and the Mechanism Insight. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2010763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, P.; Pan, H.; Fu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Du, Y.; Tang, N.; Liu, G. Increasing Solar Absorption of Atomically Thin 2D Carbon Nitride Sheets for Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1807540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Wang, D.; Li, S.; Pei, Y.; Qiao, M.; Li, Z.-H.; Zhang, J.; Zong, B. KOH−Assisted Band Engineering of Polymeric Carbon Nitride for Visible Light Photocatalytic Oxygen Reduction to Hydrogen Peroxide. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 8, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Miao, S.; Wu, S.; Hao, X.; Zhang, W.; Jia, M. Polyacrylonitrile beads supported Pd−based nanoparticles as superior catalysts for dehydrogenation of formic acid and reduction of organic dyes. Catal. Commun. 2018, 114, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zheng, J.; Hao, X.; Wei, G.; Bai, H.; Abudula, A.; Guan, G. Selective dehydrogenation of aqueous formic acid over multifunctional γ−Mo2N catalysts at a temperature lower than 100 °C. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 313, 121445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hu, S.; Zhang, X. Unveiling the formic acid dehydrogenation dynamics steered by Strength-Controllable internal electric field from barium titanate. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 491, 151703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, C.; Keane, M.A. Palladium supported on structured and nonstructured carbon: A consideration of Pd particle size and the nature of reactive hydrogen. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2008, 322, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.Y.; Mullen, G.M.; Mullins, C.B. Hydrogen Adsorption and Absorption with Pd−Au Bimetallic Surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 19535–19543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Xiong, M.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, B.; Qin, Y.; Gao, Z. Improving the Efficiency of Hydrogen Spillover by an Organic Molecular Decoration Strategy for Enhanced Catalytic Hydrogenation Performance. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 4003–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhan, S.; Liu, K.; Qiao, M.; Liu, N.; Qin, R.; Xiao, L.; You, P.; Jing, W.; Zheng, N. Heterogeneous Hydrogenation with Hydrogen Spillover Enabled by Nitrogen Vacancies on Boron Nitride-Supported Pd Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202217191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Gao, R.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhou, B.; Wang, C.; Ye, S.; Du, H.; Song, J.; Wei, G.; et al. Functional groups and nitrogen vacancies synergistically boost the activity and stability of Pd/C3N4 for selective hydrogenation of quinoline. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2025, 706, 120493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Cao, D.; Cheng, D. Constructing a Highly Active Pd Atomically Dispersed Catalyst for Cinnamaldehyde Hydrogenation: Synergistic Catalysis between Pd−N3 Single Atoms and Fully Exposed Pd Clusters. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Du, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Ye, S.; Song, J.; Wei, G.; Qiu, W. Improving the Efficiency of Hydrogen Spillover by an Alkali Treatment Strategy for Boosting Formic Acid Dehydrogenation Performance. Catalysts 2026, 16, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010026

Du H, Chen Y, Wang H, Zhu J, Ye S, Song J, Wei G, Qiu W. Improving the Efficiency of Hydrogen Spillover by an Alkali Treatment Strategy for Boosting Formic Acid Dehydrogenation Performance. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Hao, Yun Chen, Hanyang Wang, Jishen Zhu, Siyi Ye, Jianwei Song, Gaixia Wei, and Wenge Qiu. 2026. "Improving the Efficiency of Hydrogen Spillover by an Alkali Treatment Strategy for Boosting Formic Acid Dehydrogenation Performance" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010026

APA StyleDu, H., Chen, Y., Wang, H., Zhu, J., Ye, S., Song, J., Wei, G., & Qiu, W. (2026). Improving the Efficiency of Hydrogen Spillover by an Alkali Treatment Strategy for Boosting Formic Acid Dehydrogenation Performance. Catalysts, 16(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010026