Promoted CO2 Desorption in N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)ethylenediamine Solutions Catalyzed by Histidine

Abstract

1. Introduction

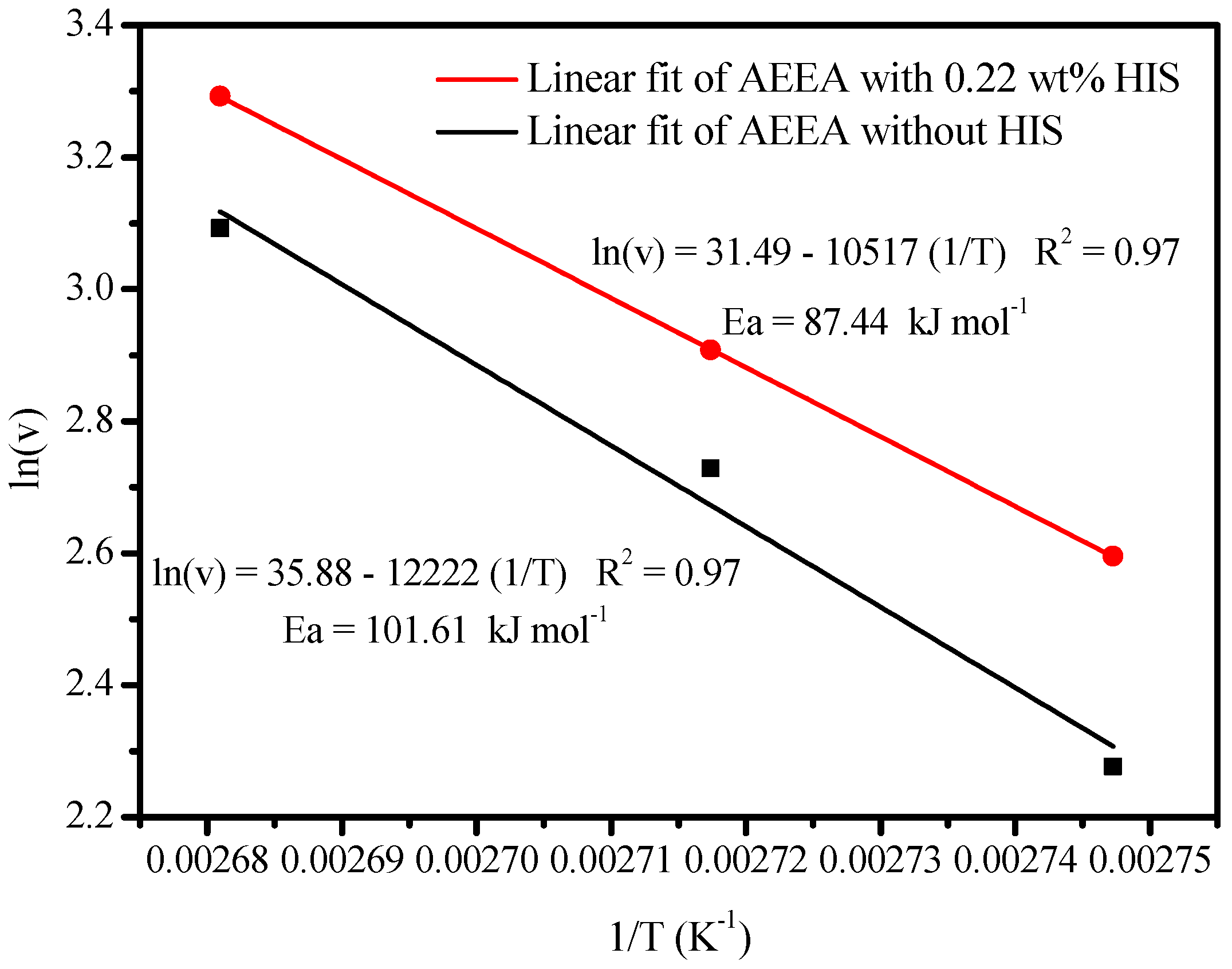

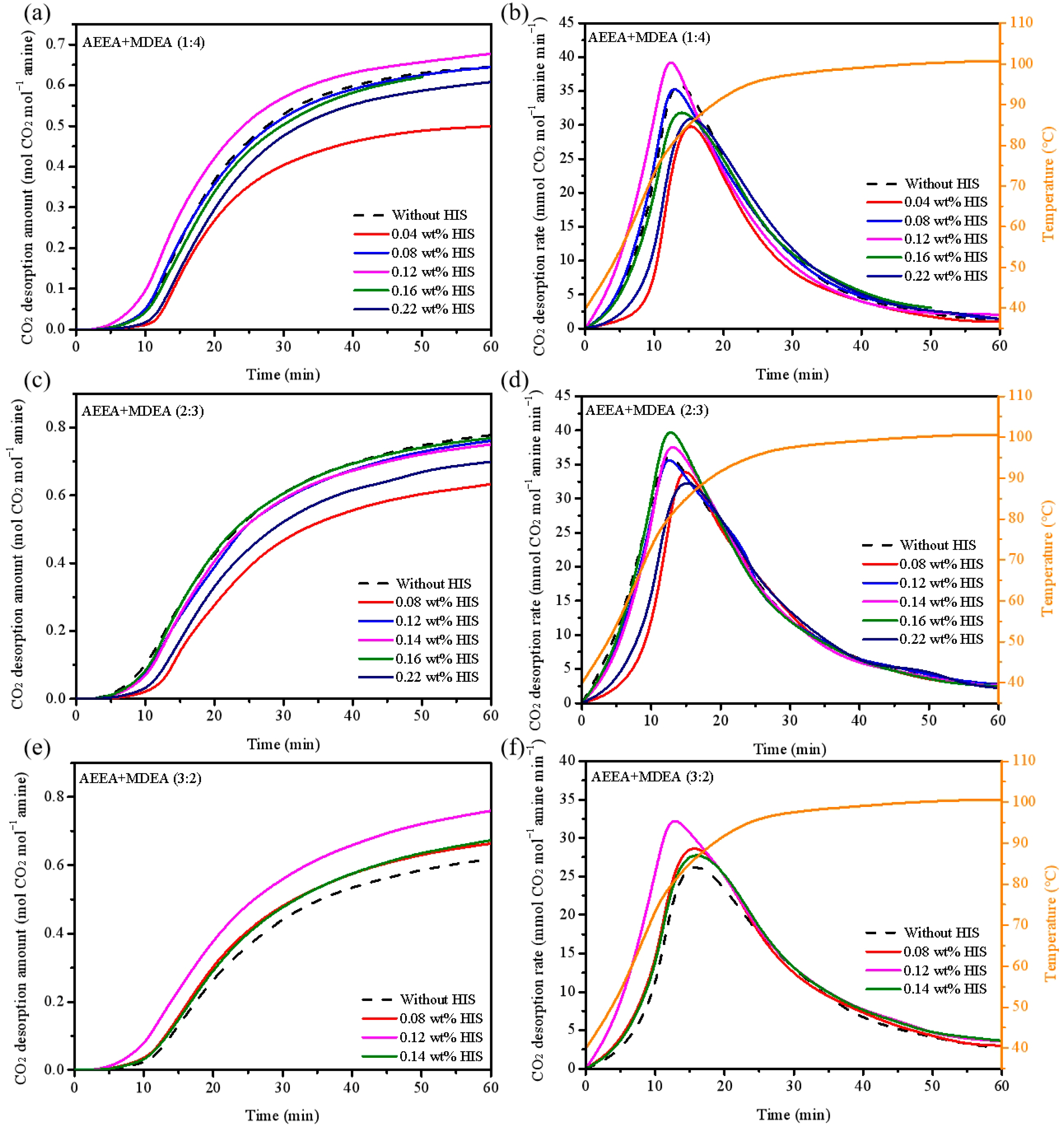

2. Results and Discussion

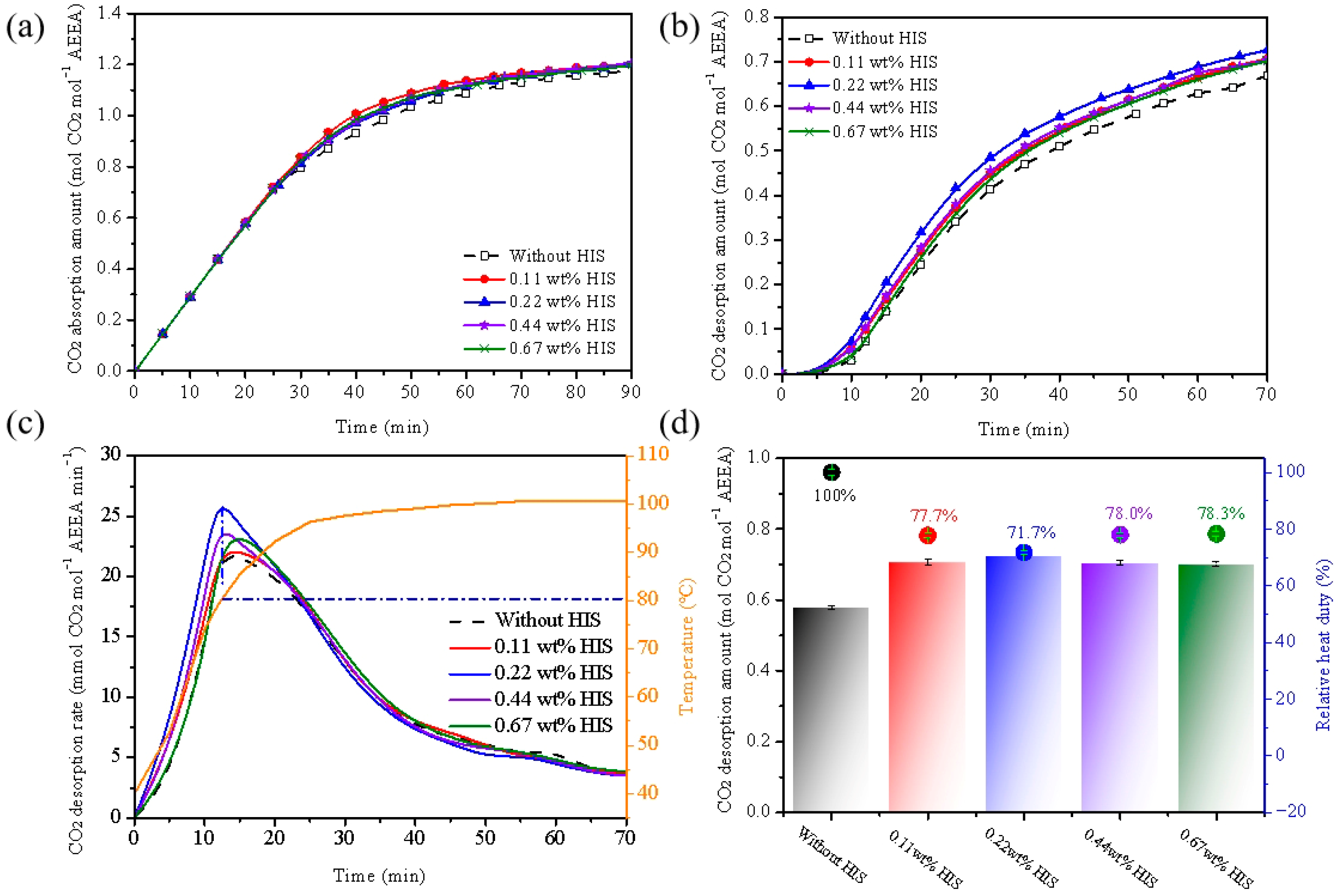

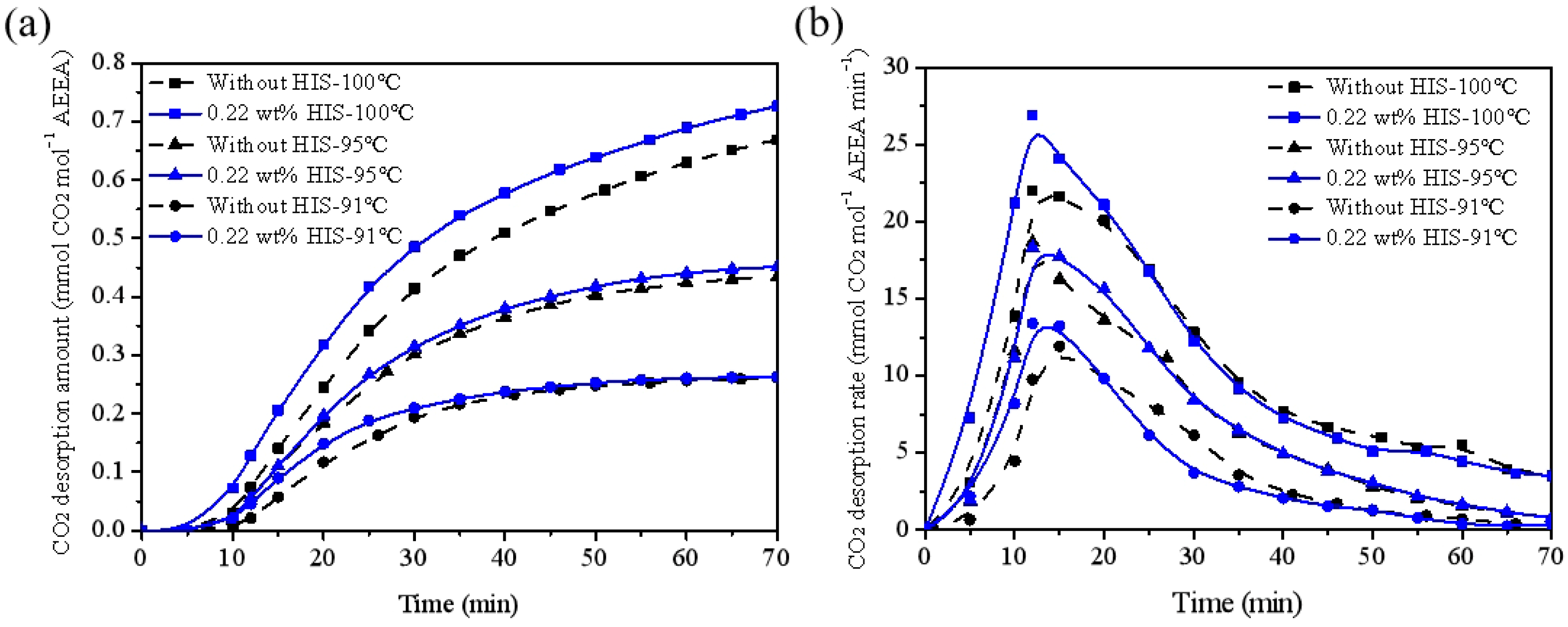

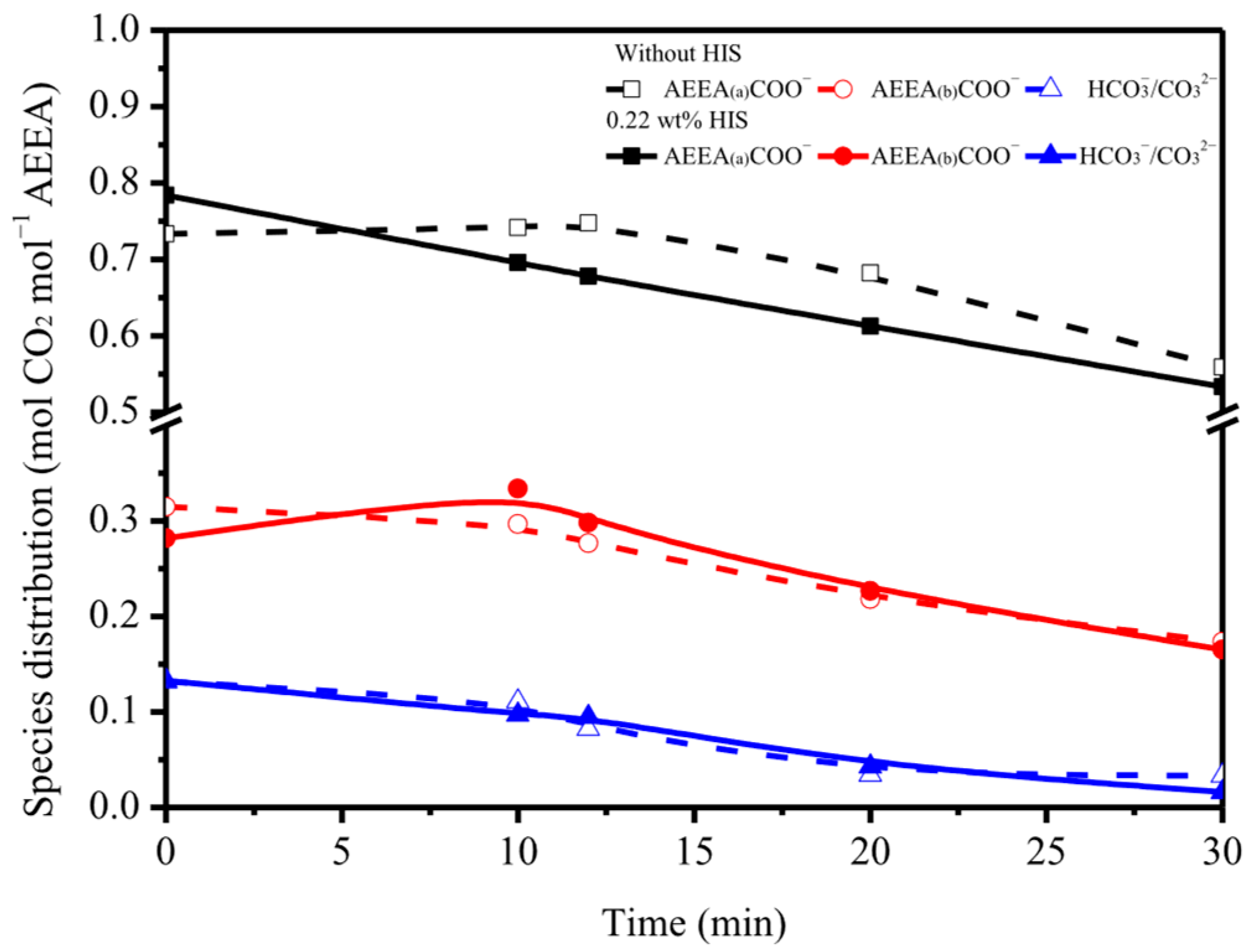

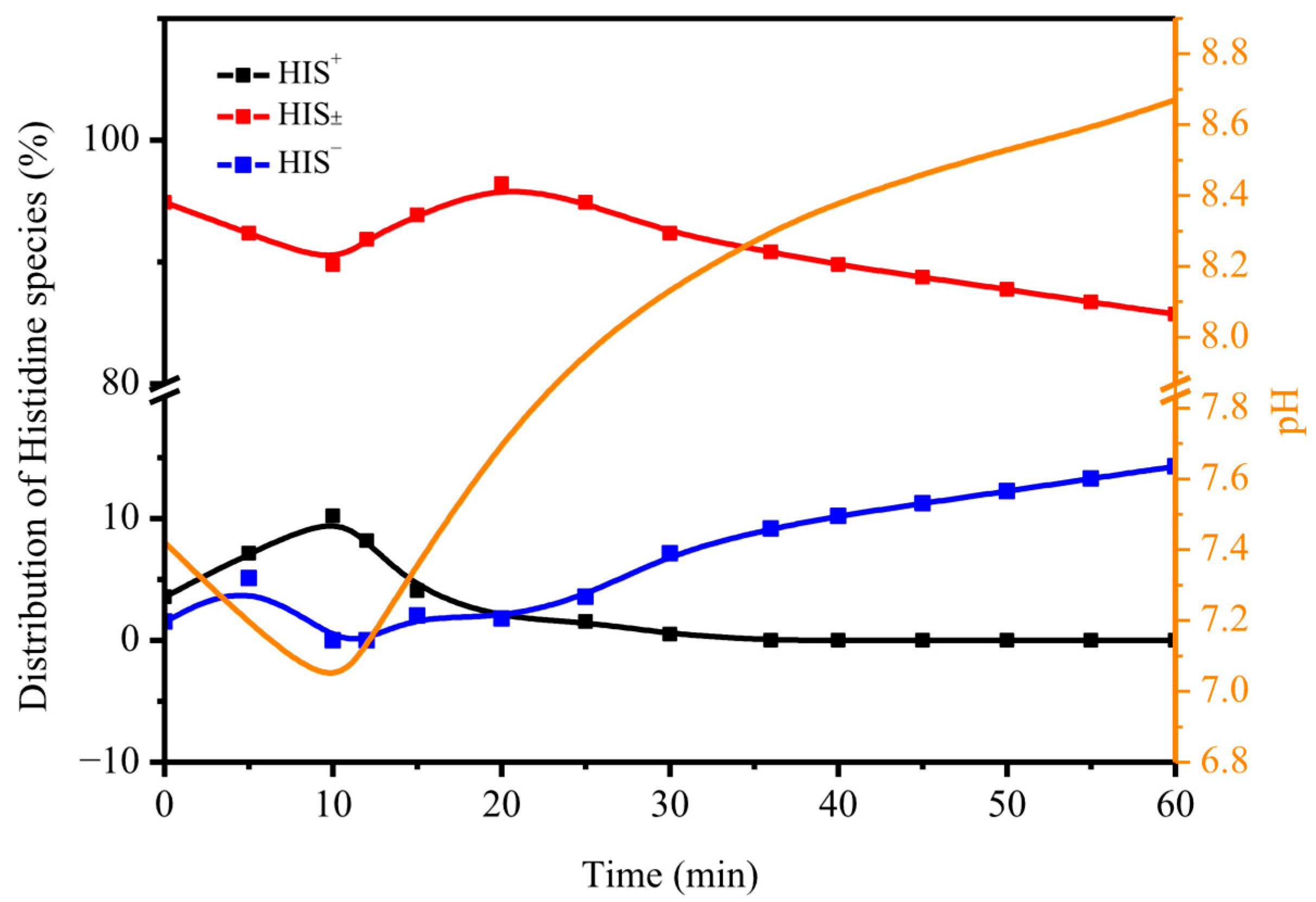

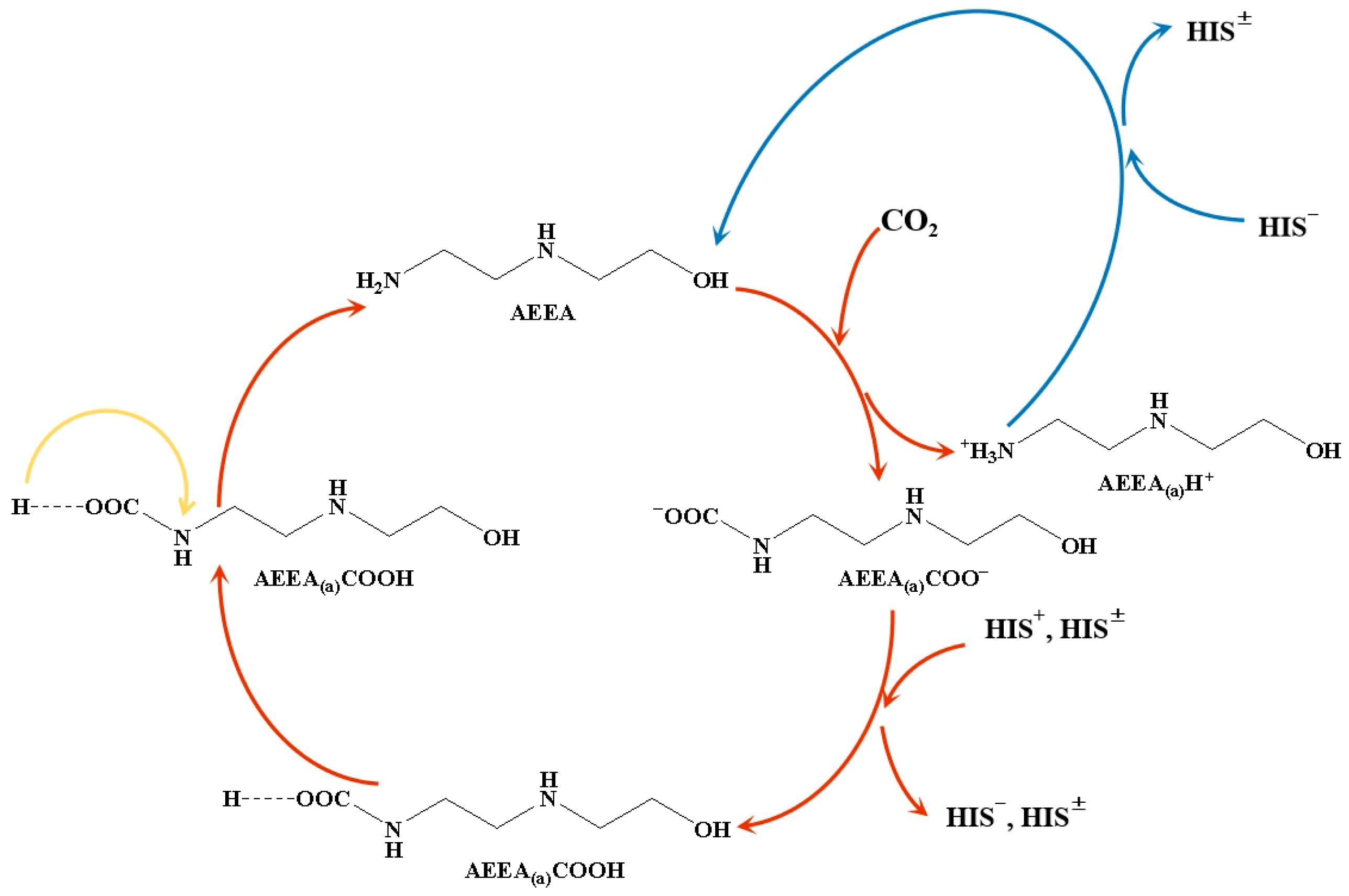

2.1. Effect of HIS on CO2 Absorption and Desorption

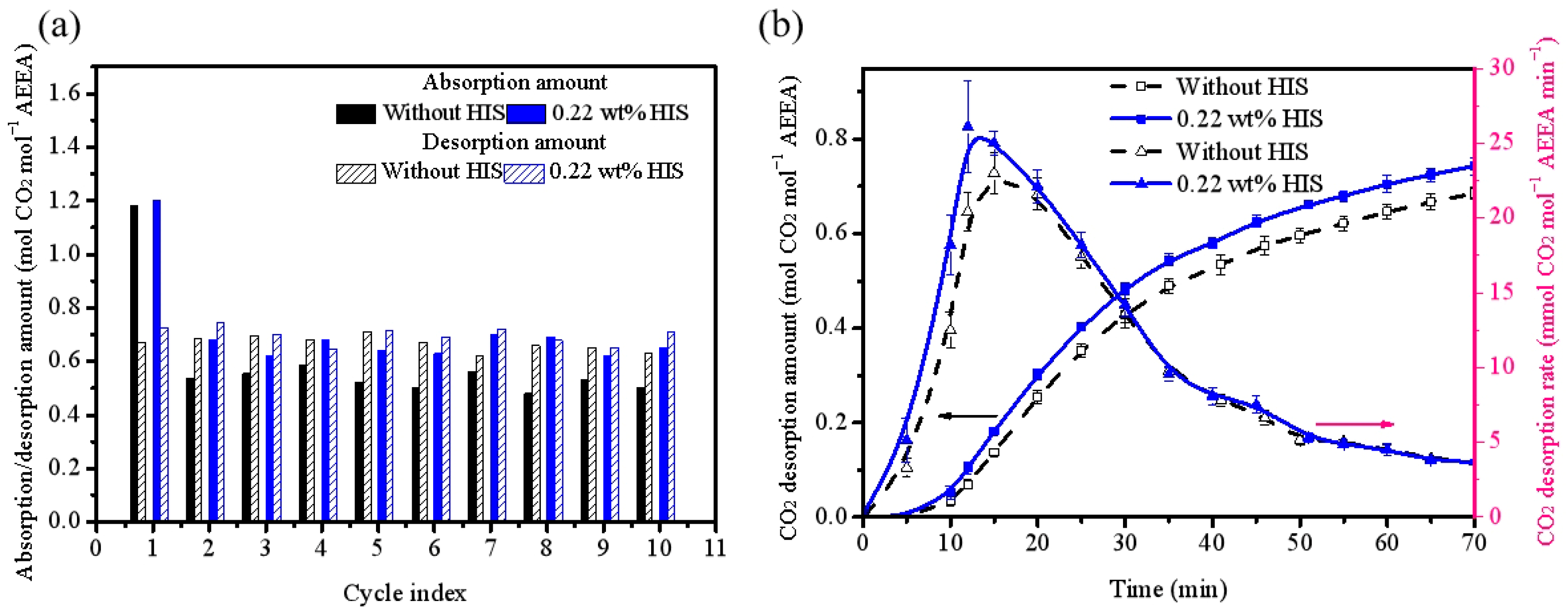

2.2. Sorbent Stability

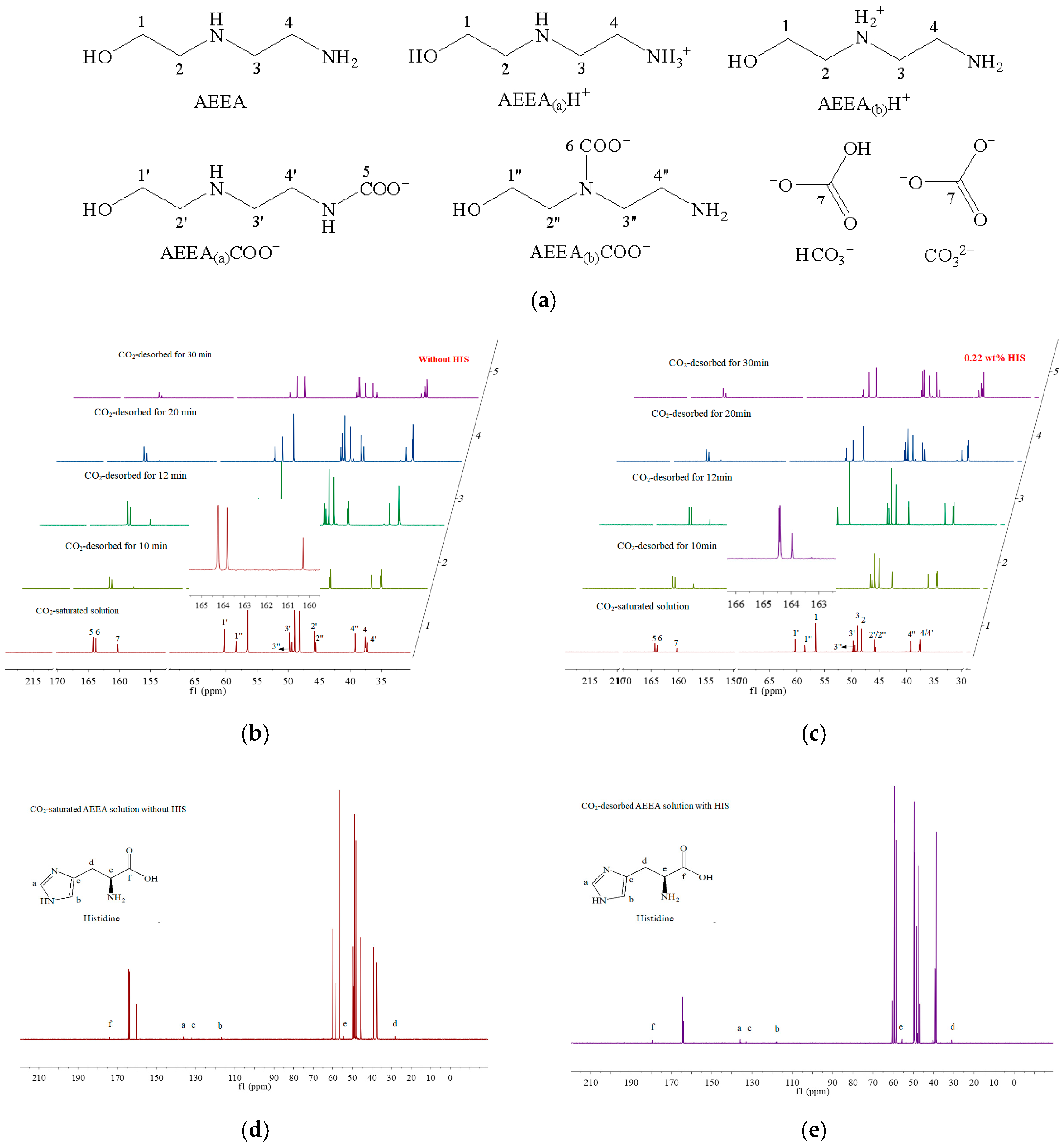

2.3. Sorbent Characterization

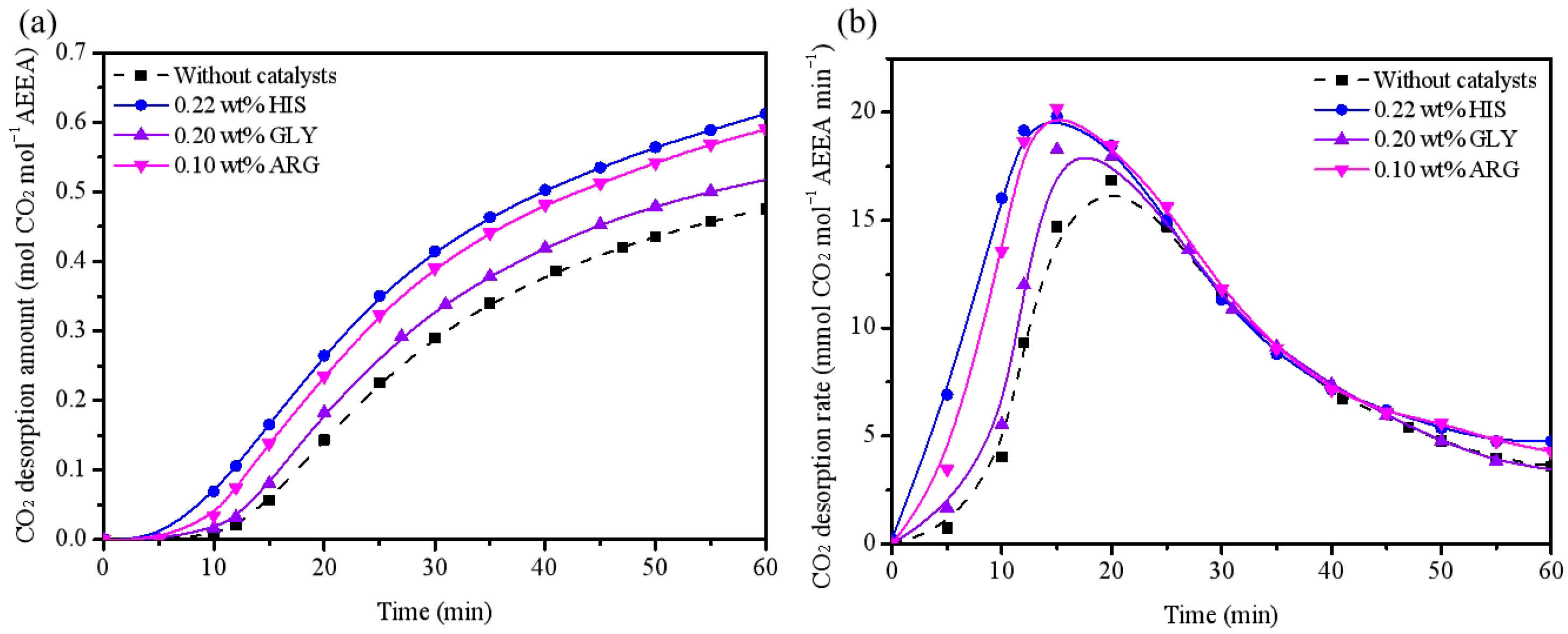

2.4. Comparing with Other Amino Acid

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. CO2-Absorption–Desorption Experiments

3.3. Characterization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belmabkhout, Y.; Sernaguerrero, R.; Sayari, A. Adsorption of CO2-Containing Gas Mixtures over Amine-Bearing Pore-Expanded MCM-41 Silica: Application for Gas Purification. Adsorpt. J. Int. Adsorpt. Soc. 2009, 49, 79–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idem, R.; Wilson, M.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P.; Chakma, A.; Veawab, A.; Aroonwilas, A.; Gelowitz, D. Pilot Plant Studies of the CO2 Capture Performance of Aqueous MEA and Mixed MEA/MDEA Solvents at the University of Regina CO2 Capture Technology Development Plant and the Boundary Dam CO2 Capture Demonstration Plant. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2005, 45, 2414–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, N.; Mussati, S.; Scenna, N. Optimization of post-combustion CO2 process using DEA–MDEA mixtures. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2011, 89, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, S.; Wetherald, R.T. On the Distribution of Climate Change Resulting from an Increase in CO2 Content of the Atmosphere. J. Atmos. Sci. 1980, 37, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, M.; Chen, S.; Qi, T.; Zhang, Y. Investigation of CO2 Capture in Nonaqueous Ethylethanolamine Solution Mixed with Porous Solids. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2018, 63, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, L.L.; Pandey, S.; Ravula, S.; Pandey, S.; Zhao, H.; Baker, G.A.; Baker, S.N. Ternary Deep Eutectic Solvents Tasked for Carbon Dioxide Capture. Acs Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 2117–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, D.V.; Dindi, A.; Abu-Zahra, M.R.M. One-Step Process Using CO2 for the Preparation of Amino-Functionalized Mesoporous Silica for CO2 Capture Application. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3170–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Jiang, J.; Li, K.; Tian, S.; Liu, Z.; Shi, J.; Chen, X.; Fei, J.; Lu, Y. Cyclic Performance of Waste-Derived SiO2 Stabilized, CaO-Based Sorbents for Fast CO2 Capture. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 7004–7012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.K.; Balsora, H.K.; Varshney, P. Progress and trends in CO2 capture/separation technologies: A review. Energy 2012, 46, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. Enhanced Performance of a Novel Polyvinyl Amine/Chitosan/Graphene Oxide Mixed Matrix Membrane for CO2 Capture. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.H.; Al-Rashed, O.; Merchant, S.Q. Opportunities for faster carbon dioxide removal: A kinetic study on the blending of methyl monoethanolamine and morpholine with 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 74, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- And, A.A.; Veawab, A. Characterization and Comparison of the CO2 Absorption Performance into Single and Blended Alkanolamines in a Packed Column. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2004, 43, 2228–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, P. Use of monoethanolamine (MEA) for CO2 capture in a global scenario: Consequences and alternatives. Desalination 2016, 380, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Shi, H.; Lee, J.Y. CO2 absorption mechanism in amine solvents and enhancement of CO2 capture capability in blended amine solvent. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 45, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Naami, A.; Idem, R.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P. Catalytic and non catalytic solvent regeneration during absorption-based CO2 capture with single and blended reactive amine solvents. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2014, 26, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Borhani, T.N.; Olabi, A.G. Status and perspective of CO2 absorption process. Energy 2020, 205, 118057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivand, M.S.; Mazaheri, O.; Wu, Y.; Stevens, G.W.; Scholes, C.A.; Mumford, K.A. Catalytic Solvent Regeneration for Energy-Efficient CO2 Capture. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 18755–18788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, U.H.; Sivanesan, D.; Lim, D.H.; Nam, S.C.; Park, S.; Baek, I.H. Metal oxide catalyst-aided solvent regeneration: A promising method to economize post-combustion CO2 capture process. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 93, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, X.; Yang, J.; Gao, H.; Huang, Y.; Luo, X.; Liang, Z.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P. Reducing Energy Penalty of CO2 Capture Using Fe Promoted SO42−/ZrO2/MCM-41 Catalyst. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 6094–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xing, Y.; Zhao, D.; Lu, S.; Chen, Y.; Cui, S.; Song, X. Advancing energy-efficient CO2 capture with organic amine solutions using ionic liquid absorption promoters and zeolite molecular sieve desorption catalysts. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 363, 132094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Wei, K.; Li, Q.; Wang, R.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L. One-Step Synthesized SO42−/ZrO2-HZSM-5 Solid Acid Catalyst for Carbamate Decomposition in CO2 Capture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 13944–13952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran-Shaukat, M.; Haghani, H.; Apaiyakul, R. Efficient catalytic regeneration of amine-based solvents in CO2 capture: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tataru-Farmus, R.E.; Harja, M.; Tonucci, L.; Coccia, F.; Ciulla, M.; Lazar, L.; Soreanu, G.; Cretescu, I. Green CO2 Capture from Flue Gas Using Potassium Carbonate Solutions Promoted with Amino Acid Salts. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.C.; Sun, S.S.; Zhao, Y.; Miao, R.K.; Fan, M.; Lee, G.; Chen, Y.; Gabardo, C.M.; Yu, Y.; Qiu, C.; et al. Reactive capture of CO2 via amino acid. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

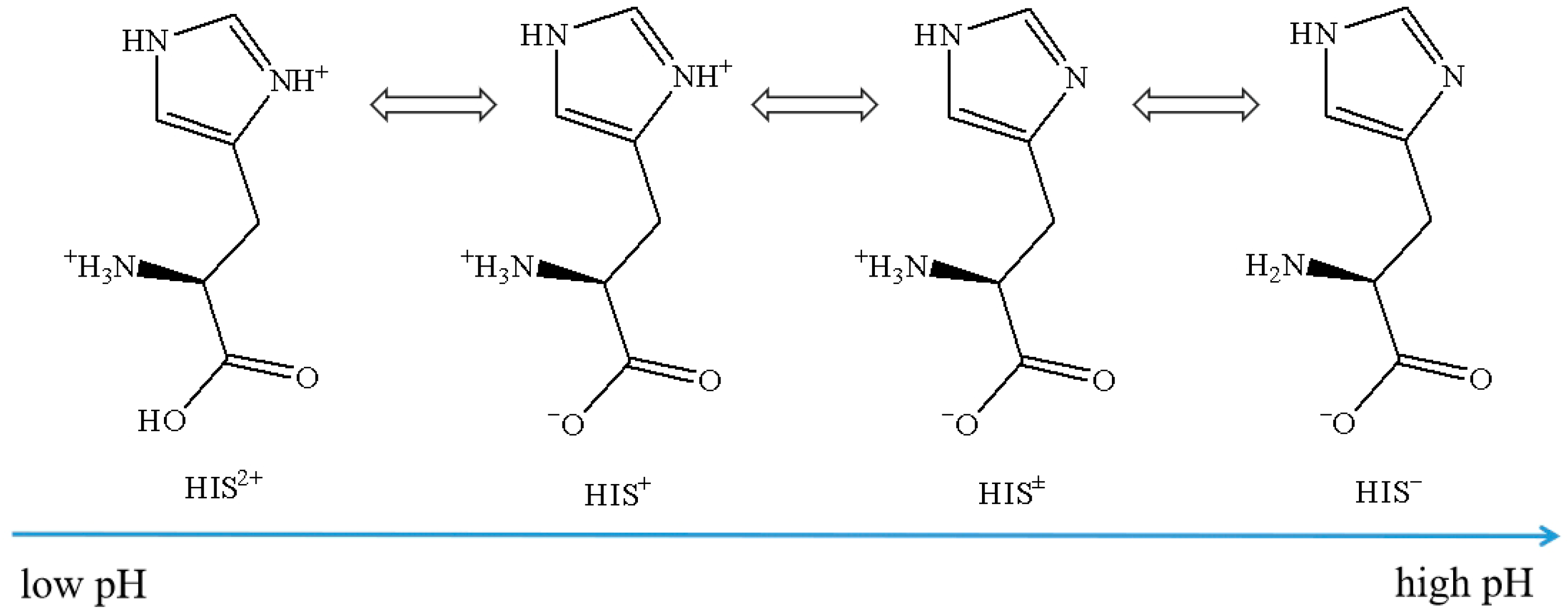

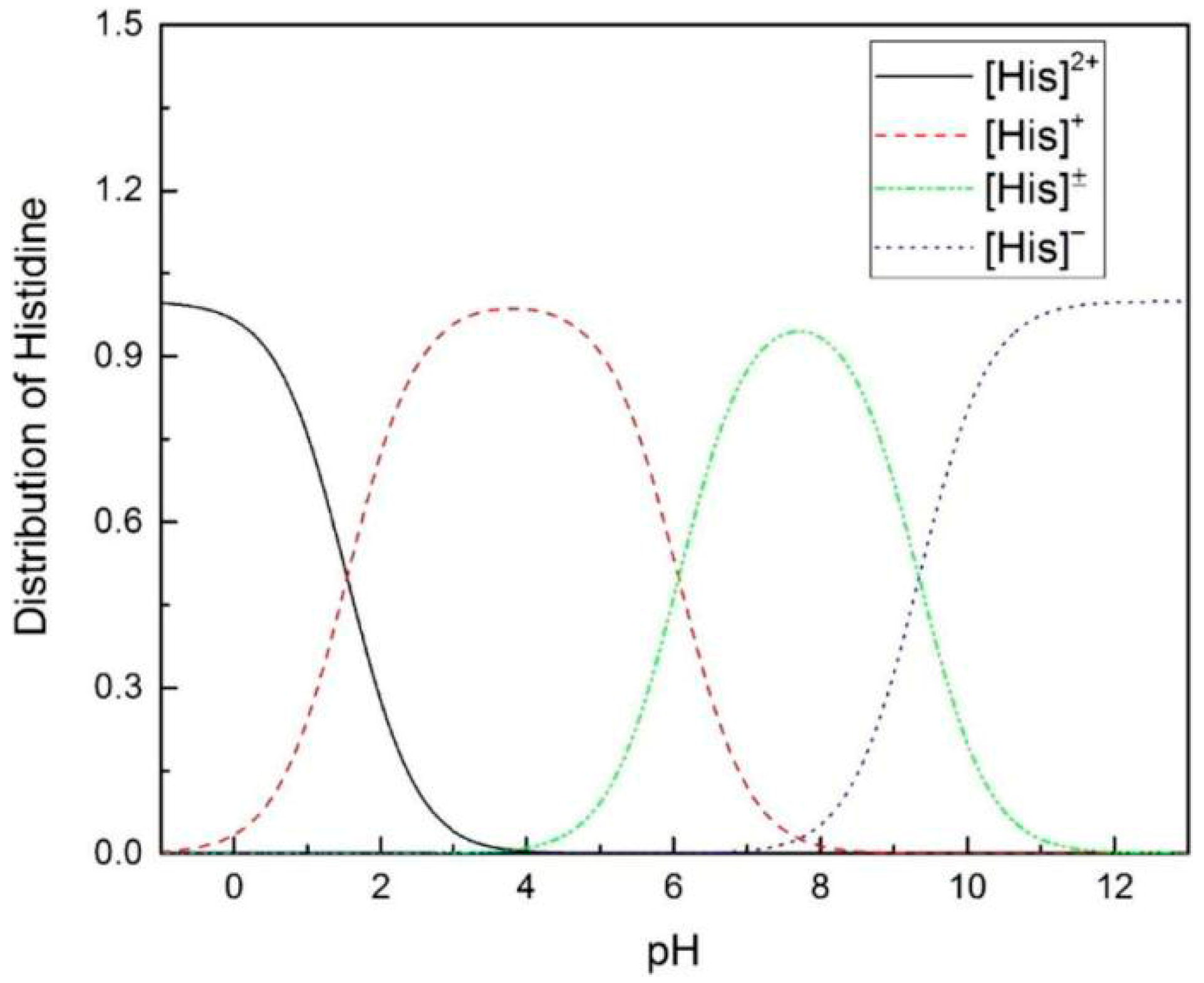

- Li, S.; Hong, M. Protonation, tautomerization, and rotameric structure of histidine: A comprehensive study by magic-angle-spinning solid-state NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Smith, K.H.; Liu, L.; Kentish, S.E.; Stevens, G.W. Reaction kinetics and mechanism between histidine and carbon dioxide. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 307, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, G.J.; Porter, C.T.; Borkakoti, N.; Thornton, J.M. Analysis of Catalytic Residues in Enzyme Active Sites. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 324, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, G.L.; Mitchell, J.B.O.; Thornton, J.M. Understanding the Functional Roles of Amino Acid Residues in Enzyme Catalysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 390, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fersht, A. Enzyme Structure and Mechanism; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York City, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Eigen, M. Proton Transfer, Acid-Base Catalysis, and Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Part I: ELEMENTARY PROCESSES. Angew. Chem. Int. Edition 2010, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, A.R.; Townsend, C.A. Intrinsic evolutionary constraints on protease structure, enzyme acylation, and the identity of the catalytic triad. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E653–E661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauwerdink, A.M.; Kazlauskas, R.J. How the Same Core Catalytic Machinery Catalyzes 17 Different Reactions: The Serine-Histidine-Aspartate Catalytic Triad of α/β-Hydrolase Fold Enzymes. Acs Catalysis 2015, 10, 6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindskog, S. Structure and mechanism of carbonic anhydrase. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 74, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raum, H.N.; Zo, F.S.; Ulrich, W. Energetics and dynamics of the proton shuttle of carbonic anhydrase II. Cell Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2023, 80, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preimesberger, M.R.; Majumdar, A.; Rice, S.L.; Que, L.; Lecomte, J.T.J. Helix-Capping Histidines: Diversity of N–H···N Hydrogen Bond Strength Revealed by 2hJNN Scalar Couplings. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 6896–6908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna Deepak, R.N.; Sankararamakrishnan, R. N–H···N Hydrogen Bonds Involving Histidine Imidazole Nitrogen Atoms: A New Structural Role for Histidine Residues in Proteins. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 3774–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.R.; Hass, M.A.S.; Hansen, D.F.; Led, J.J. Investigating metal-binding in proteins by nuclear magnetic resonance. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 1085–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styring, S.; Sjoholm, J.; Mamedov, F. Two tyrosines that changed the world: Interfacing the oxidizing power of photochemistry to water splitting in photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Bioenerg. 2012, 1817, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagba, C.V.; McCaslin, T.G.; Chi, S.H.; Perry, J.W.; Barry, B.A. Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer and a Tyrosine-Histidine Pair in a Photosystem II-Inspired β-Hairpin Maquette: Kinetics on the Picosecond Time Scale. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 1259–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tochio, N.; Kawasaki, R.; Tamari, Y.; Xu, N.; Uewaki, J.-I.; Utsunomiya-Tate, N.; Tate, S.-I. Allosteric Breakage of the Hydrogen Bond Within the Dual-Histidine Motif in the Active Site of Human Pin1 PPlase. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 5242–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Fu, R.; Nishimura, K.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.-X.; Busath, D.D.; Vijayvergiya, V.; Cross, T.A. Histidines, heart of the hydrogen ion channel from influenza A virus: Toward an understanding of conductance and proton selectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 6865–6870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Ben-Abu, Y.; Hen, S.; Zilberberg, N. A Novel Mechanism for Human K2P2.1 Channel Gating. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 19448–19455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiland, R.H.; Dingman, J.C.; Cronin, D.B. Heat Capacity of Aqueous Monoethanolamine, Diethanolamine, N-Methyldiethanolamine, and N-Methyldiethanolamine-Based Blends with Carbon Dioxide. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1997, 42, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sema, T.; Naami, A.; Fu, K.; Edali, M.; Liu, H.; Shi, H.; Liang, Z.; Idem, R.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P. Comprehensive mass transfer and reaction kinetics studies of CO2 absorption into aqueous solutions of blended MDEA–MEA. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 209, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, W.; Bruggink, S.; Beyad, Y.; Luo, W.; Melián-Cabrera, I.; Puxty, G.; Feron, P. CO2 absorption into aqueous amine blended solutions containing monoethanolamine (MEA), N,N-dimethylethanolamine (DMEA), N,N-diethylethanolamine (DEEA) and 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP) for post-combustion capture processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 126, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liang, Z.; Liu, H.; Rongwong, W.; Luo, X.; Idem, R.; Yang, Q. Study of Formation of Bicarbonate Ions in CO2-Loaded Aqueous Single 1DMA2P and MDEA Tertiary Amines and Blended MEA–1DMA2P and MEA–MDEA Amines for Low Heat of Regeneration. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 3710–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Gao, H.; Liang, Z. Evaluating CO2 desorption performance in CO2-loaded aqueous tri-solvent blend amines with and without solid acid catalysts. Appl. Energy 2018, 218, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Lu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, L.; Jiang, Y.; Jia, C.; Chen, S. Low–energy–consuming CO2 capture by liquid–liquid biphasic absorbents of EMEA/DEEA/PX. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 138490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Blank Group | Control Group | Control Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AEEA Solvent at ~100 °C | AEEA Solvent at Different Temperature | Different Solvent at ~100 °C | ||||

| ~95 °C | ~91 °C | AEEA + MDEA (3:2) | AEEA + MDEA (2:3) | AEEA + MDEA (1:4) | ||

| αdes | 0.669 → 0.726 | 0.434 → 0.451 | 0.260 → 0.263 | 0.618 → 0.713 | 0.780 → 0.774 | 0.657 → 0.678 |

| γdes | 8.5 | 3.9 | −1.1 | 15.3 | −0.7 | 3.2 |

| δdes | 22.03 → 26.91 | 18.70 → 18.33 | 11.91 → 13.21 | 28.04 → 33.87 | 38.22 → 42.48 | 36.86 → 42.58 |

| εdes | 22.1 | −2.0 | 10.9 | 20.8 | 11.1 | 15.5 |

| ∆t | 12 → 12 | 12 → 12 | 15 → 15 | 15 → 12 | 12 → 12 | 12 → 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; Xing, G.; Zhang, L.; Chang, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Promoted CO2 Desorption in N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)ethylenediamine Solutions Catalyzed by Histidine. Catalysts 2026, 16, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010024

Chen S, Zhang X, Xing G, Zhang L, Chang L, Xu Y, Zhang Y. Promoted CO2 Desorption in N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)ethylenediamine Solutions Catalyzed by Histidine. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Siming, Xinzhu Zhang, Guangfei Xing, Lei Zhang, Le Chang, Yubing Xu, and Yongchun Zhang. 2026. "Promoted CO2 Desorption in N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)ethylenediamine Solutions Catalyzed by Histidine" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010024

APA StyleChen, S., Zhang, X., Xing, G., Zhang, L., Chang, L., Xu, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2026). Promoted CO2 Desorption in N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)ethylenediamine Solutions Catalyzed by Histidine. Catalysts, 16(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010024