In Situ Anchoring of CQDs-Induced CuO Quantum Dots on Ultrafine TiO2 Nanowire Arrays for Enhanced Photocatalysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

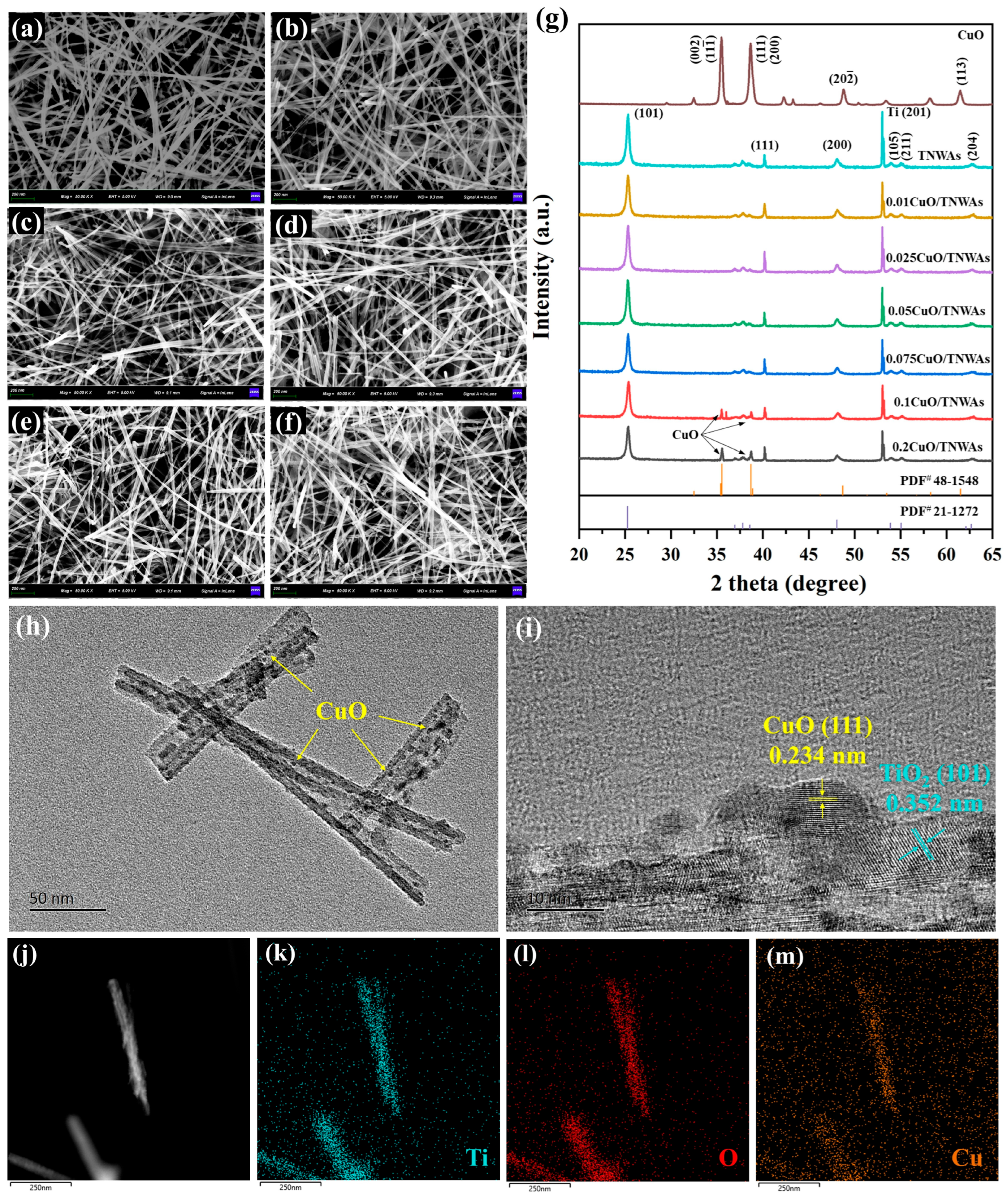

2.1. Morphology and Composition of CuO QDs/TNWAs

2.2. Chemical State Analysis of CuO QDs/TNWAs

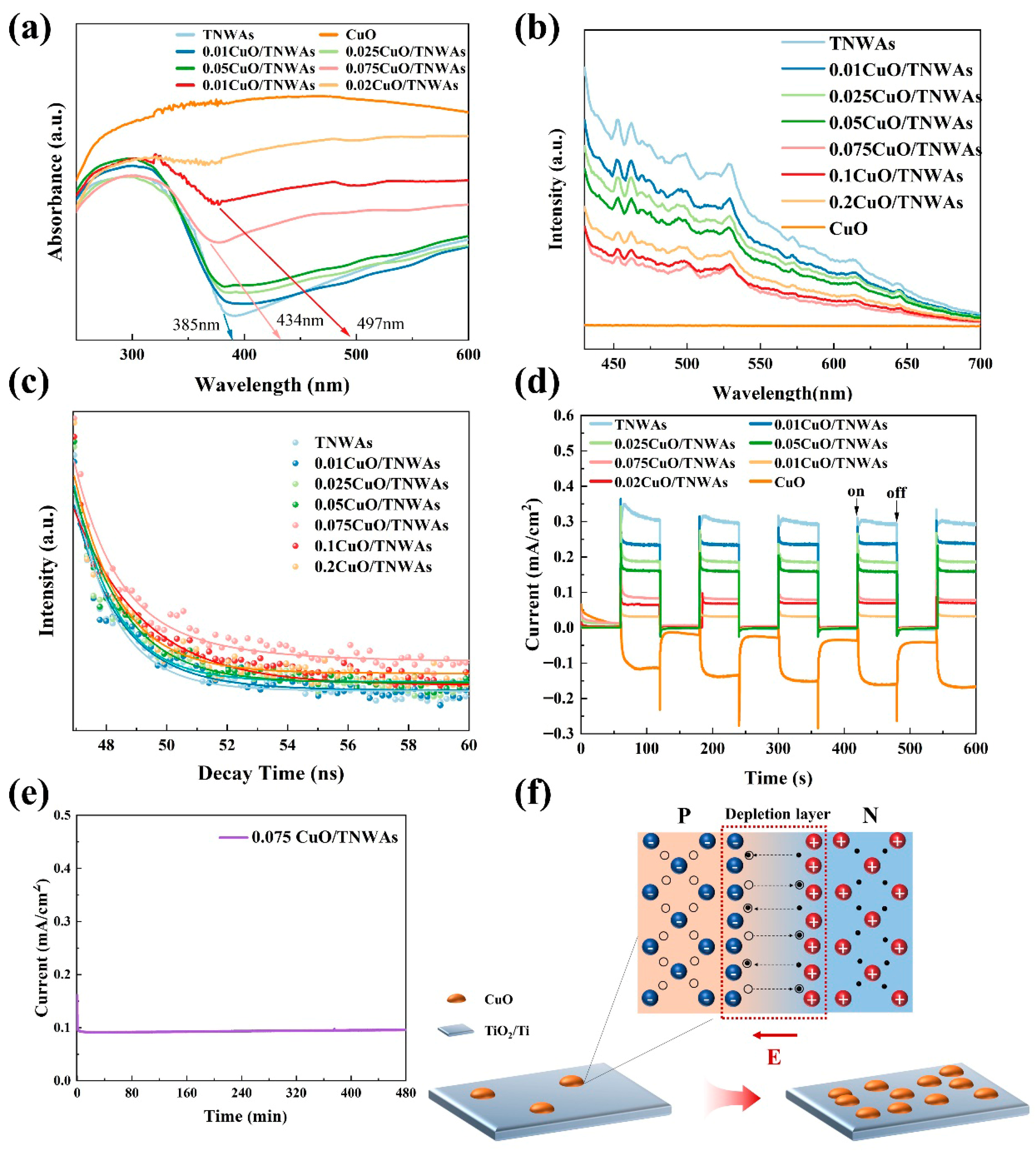

2.3. Performance Analysis of CuO QDs/TNWAs

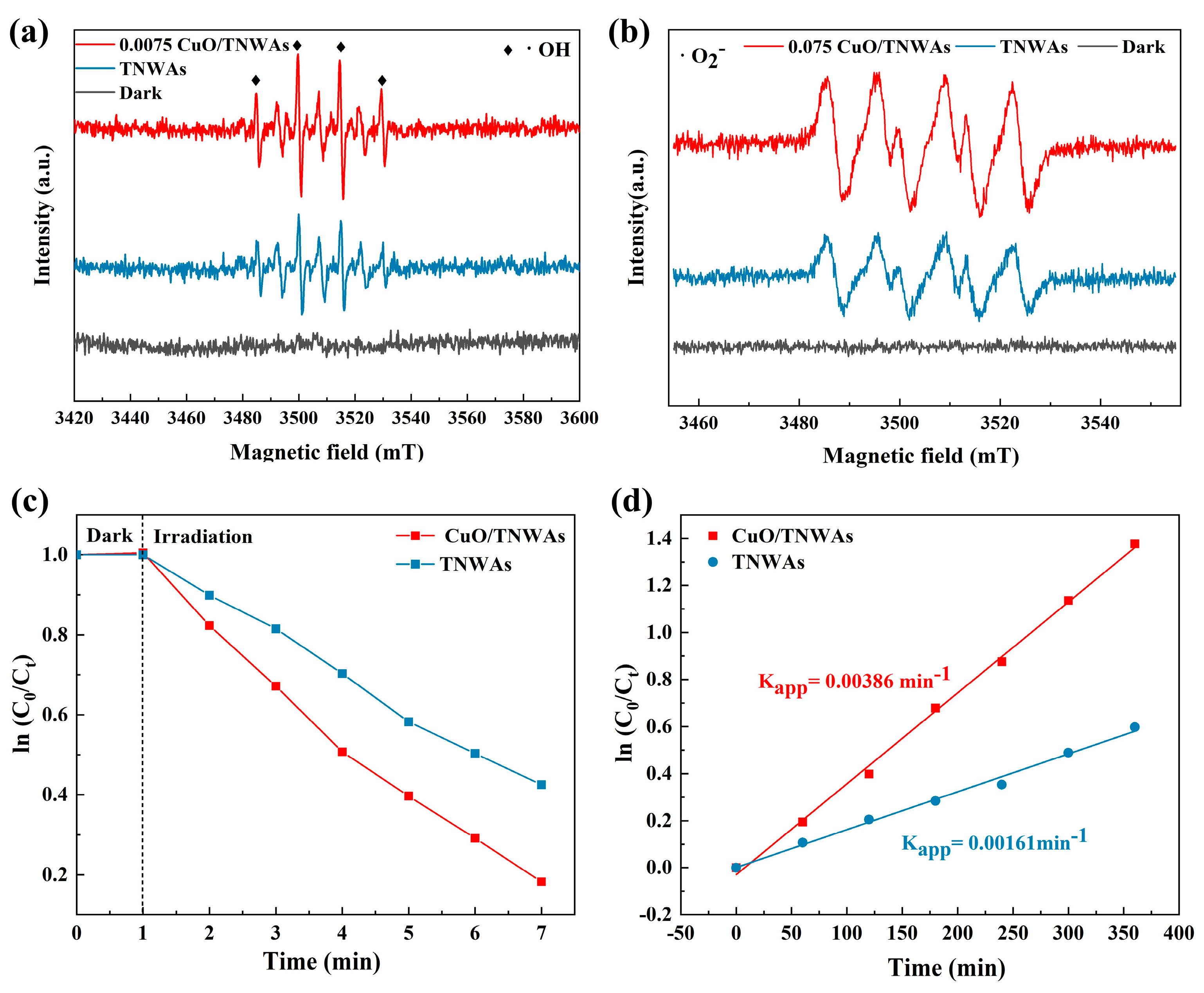

2.4. Degradation Performance of CuO QDs/TNWAs for BPA

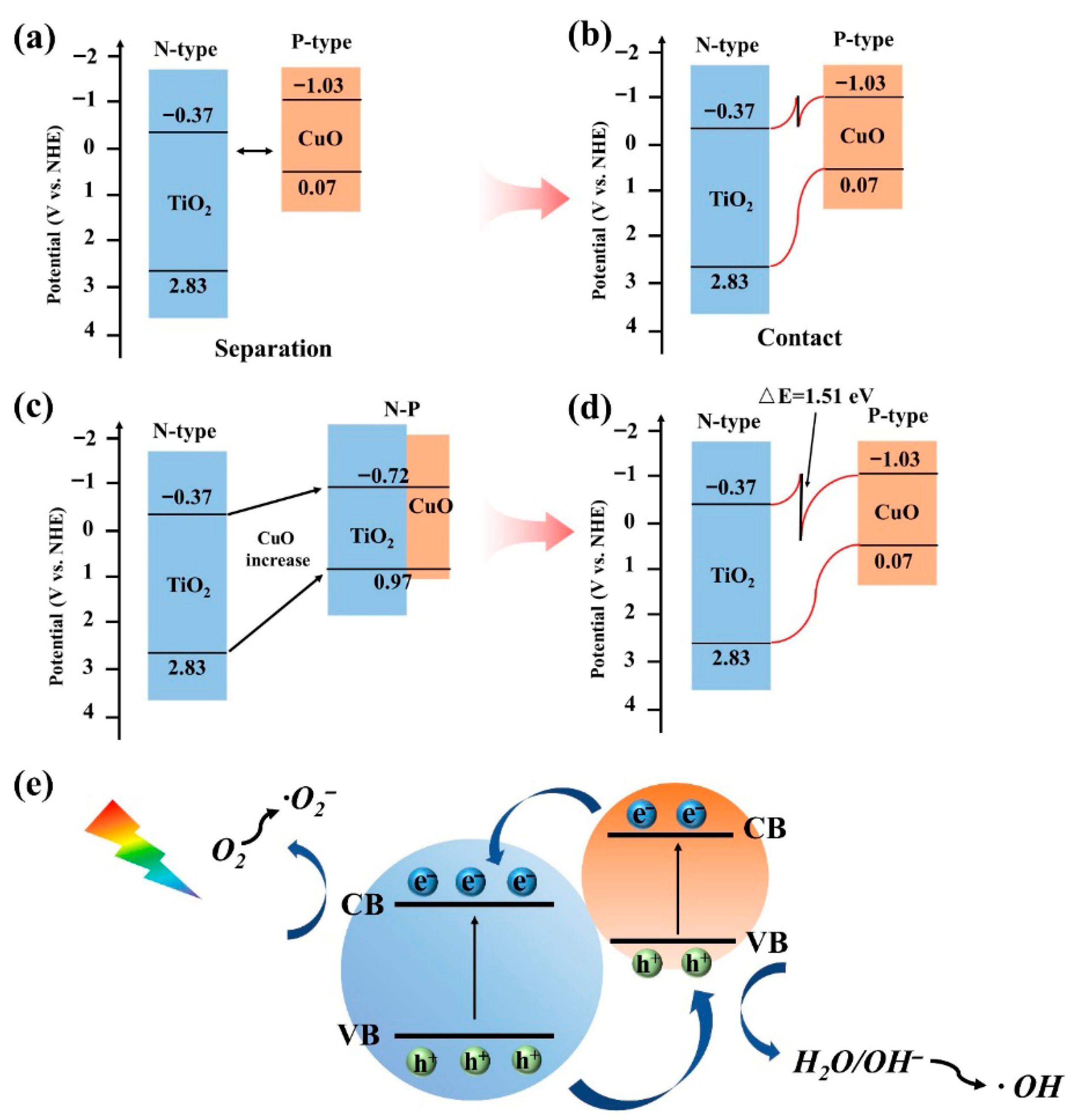

2.5. Mechanism Investigation of P–N Heterojunction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of CQDs/TNWAs

3.3. Preparation of CuO QDs/TNWAs

3.4. Degradation of BPA

3.5. Characterization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choi, J.-S.; Kim, S.; Choi, Y.; Kim, K.B.; Kim, H.-J.; Park, T.J.; Park, Y.M. Ag-Decorated CuO NW@TiO2 Heterojunction Thin Film for Improved Visible Light Photocatalysis. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 34, 102380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadi, M.W.; Mohamed, R.M.; Ismail, A.A. Uniform Dispersion of CuO Nanoparticles on Mesoporous TiO2 Networks Promotes Visible Light Photocatalysis. Ceram. Int. 2020, 7, 8819–8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Medrano, M.G.; Kowalska, E.; Lehoux, A.; Herissan, A.; Ohtani, B.; Bahena, D.; Briois, V.; Colbeau-Justin, C.; Rodríguez-López, J.L.; Remita, H. Surface Modification of TiO2 with Ag Nanoparticles and CuO Nanoclusters for Application in Photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 4120–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.S.; Mahdjoub, N.; Vishnyakov, V.; Kriek, R. The Effect of Crystalline Phase (Anatase, Brookite and Rutile) and Size on the Photocatalytic Activity of Calcined Polymorphic Titanium Dioxide (TiO2). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 150, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Benali, A.; Shulenburger, L.; Krogel, J.T.; Heinonen, O.; Kent, P.R.C. Phase Stability of TiO2 Polymorphs from Diffusion Quantum Monte Carlo. New J. Phys. 2016, 18, 113049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamakhel, A.; Mahdjoub, N.; Vishnyakov, V.; Kriek, R. Tunable Composition Aqueous-Synthesized Mixed-Phase TiO2 Nanocrystals for Photo-Assisted Water Decontamination: Comparison of Anatase, Brookite and Rutile Photocatalysts. Catalysts 2020, 10, 407. [Google Scholar]

- Harada, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Okazaki, M.; Mallouk, T.E.; Maeda, K. Visible-light H2 evolution using dye-sensitized TiO2: Effects of physicochemical properties of TiO2 on excited carrier dynamics and activity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 36997–37007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Shah, R.; Khan, J.A.; Shah, N.S.; Al-Anazi, A.; Alelyani, S.S.; Kavil, Y.N.; Castro-Muñoz, R.; Boczkaj, G. TiO2 and Non-Metal Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Applications for Green Energy Production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2025, 149, 150024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayegan, Z.; Haghighat, F.; Lee, C. Surface Fluorinated Ce-Doped TiO2 Nanostructure Photocatalyst: A Trap and Remove Strategy to Enhance the VOC Removal from Indoor Air Environment. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 125932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Jin, P.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Xu, H.; Song, G.; Du, R. Carbon Quantum Dots/Ag Sensitized TiO2 Nanotube Film for Applications in Photocathodic Protection. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 797, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synthiya, S.; Thilagavathi, T.; Uthrakumar, R.; Renuka, R.; Kaviyarasu, K. Studies of pure TiO2 and CdSe doped TiO2 nanocomposites from structural, optical, electrochemical, and photocatalytic perspectives. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasekaran, L.; Pachaiappan, R.; Kumar, P.S.; Hoang, T.K.A.; Rajendran, S.; Durgalakshmi, D.; Soto-Moscoso, M.; Cornejo-Ponce, L.; Gracia, F. Visible Light Driven Exotic p (CuO)-n (TiO2) Heterojunction for the Photodegradation of 4-Chlorophenol and Antibacterial Activity. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Chu, H.W.; Li, D.C. Enhanced Optical Nonlinearity and Ultrafast Carrier Dynamics of TiO2/CuO Nanocomposites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 237, 109860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, P.; Eslami, A.M.; Bahrami, A.; Hosseini-Abari, A.; Saber, F.Y.; Mohammadi, R.; Yazdan Mehr, M. Surface Modification of TiO2 Nanoparticles with CuO for Visible-Light Antibacterial Applications and Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 33875–33885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, B.; Kerimoglu, I.; Onbül, B.; Demirbiken, A.; Dursun, S.; Cihankaya, I.; Kalem, V.; Akyildiz, H. Hydrothermal/Electrospinning Synthesis of CuO Plate-Like Particles/TiO2 Fibers Heterostructures for High-Efficiency Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes and Phenolic Pollutants. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020, 109, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Tian, Z.; Li, L.; Lu, Y.; Xu, X.; Hou, J. Loading Nano-CuO on TiO2 Nanomeshes towards Efficient Photodegradation of Methylene Blue. Catalysts 2022, 12, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Das, K.; Chakrabarti, K.; Jana, D.; De, S.K.; De, S. Highly Efficient Photocatalytic Activity of CuO Quantum Dot Decorated rGO Nanocomposites. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2016, 49, 315107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Godiksen, A.L.; Mamahkel, A.; Søndergaard-Pedersen, F.; Rios-Carvajal, T.; Marks, M.; Lock, N.; Rasmussen, S.B.; Iversen, B.B. Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO Using Phase-Pure Anatase, Rutile, and Brookite TiO2 Nanocrystals. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 15324–15334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; He, W.; Yang, T.; Ji, H.; Liu, W.; Lei, J.; Liu, Y.; Cai, Z. Ternary TiO2/WO3/CQDs Nanocomposites for Enhancing Photocatalytic Mineralization of Aqueous Cephalexin: Degradation Mechanism and Toxicity Eval. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 412, 128679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Zhou, M.; He, Y.X.; Zhou, Z.R.; Sun, Z.Z. In Situ Loading CuO Quantum Dots on TiO2 Nanosheets as Cocatalyst for Improved Photocatalytic Water Splitting. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 813, 152184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadanandam, G.; Luo, X.; Chen, X.X.; Bao, Y.W.; Homewood, K.P.; Gao, Y. Cu Oxide Quantum Dots Loaded TiO2 Nanosheet Photocatalyst for Highly Efficient and Robust Hydrogen Generation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 541, 148687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Guan, B.H.; Zafar, M.; Hira, N.e.; Khan, H.; Saheed, M.S.M. Synergistic Enhancement in PEC Hydrogen Production Using Novel GQDs and CuO Modified TiO2-Based Heterostructure Photocatalyst. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 340, 130781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; Kang, J.; Li, S.; Mao, Z.; Tu, T. CuO Nanoparticle-Loaded TiO2 Catalyst for High-Performance Photocatalytic H2O2 Gen. Small 2025, 21, e2510644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burungale, V.; Seong, C.; Bae, H.; Mane, P.; Ryu, S.; Kang, S.; Ha, J. Surface Modification of p/n Heterojunction Based TiO2-Cu2O Photoanode with a Cobalt-Phosphate (CoPi) Co-Catalyst for Effective Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 573, 151445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, X.; Hong, H.; Wang, G.; Zhang, M. Enhanced Photovoltaic Performance of Fully Flexible Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Based on Nb2O5-Coated Hierarchical TiO2 Nanowire-Nanosheet Arrays. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 364, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.Y.; Fang, L.; Xun, C.L.; Wu, F.; Huang, Q.L.; Saleem, M. Effect of Seed Layer on Growth of Rutile TiO2 Nanorod Arrays and Their Performance in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2014, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X. Hydrothermal Synthesis and Characterization of TiO2 Nanorod Arrays on Glass Substrates. Mater. Res. Bull. 2009, 44, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sheng, X.; Guan, F.Y.; Li, K.; Wang, D.D.; Chen, L.P.; Feng, X.J. Length-Independent Charge Transport of Well-Separated Single-Crystal TiO2 Long Nanowire Arrays. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 7400–7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Sun, W.; Qin, A.; Li, J.; Huang, W.; Liao, L.; Zhang, K.; Wei, B. Carbon Quantum Dots Induced One-Dimensional Ordered Growth of Single Crystal TiO2 Nanowires While Boosting Photoelectrochemistry Properties. J. Alloy. Compd. 2023, 947, 169549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Hashimoto, K.; Fujishima, A.; Chikuni, M.; Kojima, E.; Kitamura, A.; Shimohigoshi, M.; Watanabe, T. Light-induced amphiphilic surfaces. Nature 1997, 388, 431–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, V.; Amiard, G.; Sanz, R.; Boninelli, S.; Impellizzeri, G.; Privitera, V. TiO2 Coated CuO Nanowire Array: Ultrathin p–n Heterojunction to Modulate Cationic/Anionic Dye Photo-Degradation in Water. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 416, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süngü Akdoğan, Ç.Z. Copper(II) Oxide Spindle-like Nanomotors Decorated with Calcium Peroxide Nanoshell as a New Nanozyme with Photothermal and Chemodynamic Functions Providing ROS Self-Amplification, Glutathione Depletion, and Cu(I)/Cu(II) Recycling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 4422–4435. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, Y.; Cho, E.-B.; Jang, Y.J. Boosting Solar-Driven N2 to NH3 Conversion Using Defect-Engineered TiO2/CuO Heterojunction Photocatalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 620, 156812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banas-Gac, J.; Radecka, M.; Czapla, A.; Kusior, E.; Zakrzewska, K. Surface and Interface Properties of TiO2/CuO Thin Film Bilayers Deposited by RF Reactive Magnetron Sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 616, 156394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Huang, T.; Li, M.; Pan, Y.; Liao, L.; Zhang, K.; Qin, A. Low-frequency AC-photocatalysis coupling for high-efficiency removal of organic pollutants from water based on the self-powered triboelectric nanogenerator. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 16403–16413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.W.; Li, Y.L.; Zheng, Z.S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Duan, J.X. Piezoelectricity-Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation Performance of SrBi4Ti4O15/Ag2O P-N Heterojunction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 305, 122457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, G. Preparation and Characterization of Super-Hydrophilic Porous TiO2 Coating Films. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2001, 68, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Xu, K.; Zhang, X. Fabrication of Functional Super-Hydrophilic TiO2 Thin Film for pH Detection. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hao, X.; Xi, X.; Qu, J.; Li, Q. In Situ Anchoring of CQDs-Induced CuO Quantum Dots on Ultrafine TiO2 Nanowire Arrays for Enhanced Photocatalysis. Catalysts 2026, 16, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010023

Hao X, Xi X, Qu J, Li Q. In Situ Anchoring of CQDs-Induced CuO Quantum Dots on Ultrafine TiO2 Nanowire Arrays for Enhanced Photocatalysis. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleHao, Xinyu, Xiaoyang Xi, Jinwei Qu, and Qiurong Li. 2026. "In Situ Anchoring of CQDs-Induced CuO Quantum Dots on Ultrafine TiO2 Nanowire Arrays for Enhanced Photocatalysis" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010023

APA StyleHao, X., Xi, X., Qu, J., & Li, Q. (2026). In Situ Anchoring of CQDs-Induced CuO Quantum Dots on Ultrafine TiO2 Nanowire Arrays for Enhanced Photocatalysis. Catalysts, 16(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010023