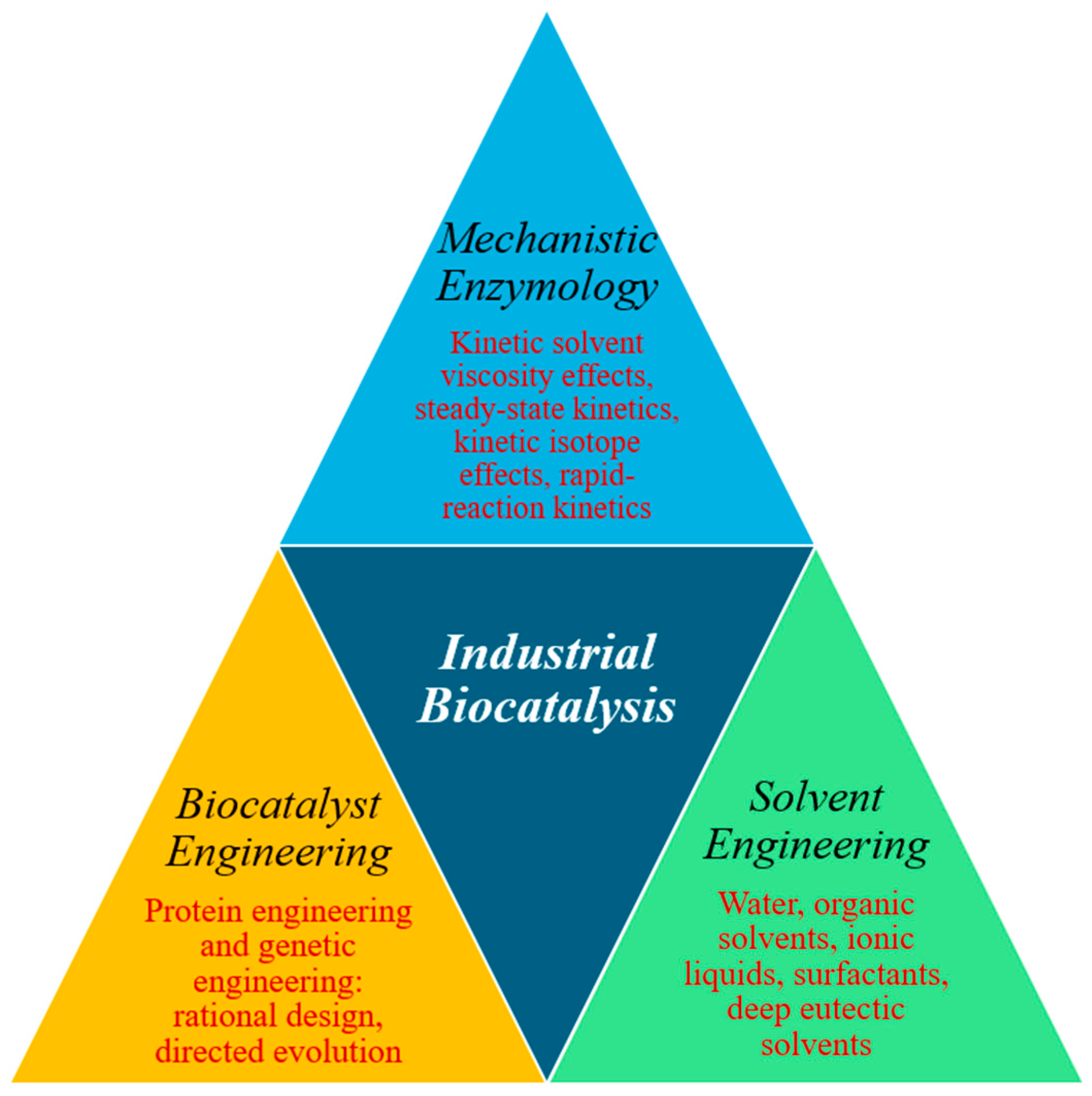

How Mechanistic Enzymology Helps Industrial Biocatalysis: The Case for Kinetic Solvent Viscosity Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Significance of Mechanistic Studies in Enzyme Engineering

3. Experimental Methods in Enzymology

4. The kcat Parameter—Enzyme Turnover Number

5. Strategies for Enhancing the Product Release Step

6. Strategies for Enhancing the Chemical Step of Catalysis

7. The kcat/Km Parameter—Enzyme Catalytic Efficiency

8. Strategies for Enhancing the Catalytic Efficiency of an Enzyme

9. Revisiting Misconceptions in Enzyme Design and Optimization

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hughes, G.; Lewis, J.C. Introduction: Biocatalysis in Industry. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.M. The Central Role of Enzymes as Biological Catalysts. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9921/ (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Agarwal, P.K. A Biophysical Perspective on Enzyme Catalysis. Biochemistry 2018, 58, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P. Enzymes in Food Processing: A Condensed Overview on Strategies for Better Biocatalysts. Enzym. Res. 2010, 2010, 862537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen: History of Enzymology with Emphasis on Food. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Handbook%20of%20Food%20Enzymology&author=PB%20Poulsen&author=H%20Klaus%20Buchholz&publication_year=2003& (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Wandrey, C.; Liese, A.; Kihumbu, D. Industrial Biocatalysis: Past, Present, and Future. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2000, 4, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosche, B.; Li, X.Z.; Hauer, B.; Schmid, A.; Buehler, K. Microbial Biofilms: A Concept for Industrial Catalysis? Trends Biotechnol 2009, 27, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Fang, B. Synthesizing Chiral Drug Intermediates by Biocatalysis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 192, 146–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.N. Synthesis of Chiral Pharmaceutical Intermediates by Biocatalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 659–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndochinwa, O.G.; Wang, Q.Y.; Amadi, O.C.; Nwagu, T.N.; Nnamchi, C.I.; Okeke, E.S.; Moneke, A.N. Current Status and Emerging Frontiers in Enzyme Engineering: An Industrial Perspective. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, D.E.; Gadda, G. Guidelines for the Functional Analysis of Engineered and Mutant Enzymes. Protein Eng. Handb. 2011, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Jiang, J.; Xiong, K.; Chen, Y.; Yao, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Mao, S.; Jiang, J.; et al. Enzyme Engineering: Performance Optimization, Novel Sources, and Applications in the Food Industry. Foods 2024, 13, 3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, U.U.; Yelmazer, B.; ÇorbacloÄY Lu, M.; Ruupunen, J.; Valjakka, J.; Turunen, O.; Binay, B.Y. Functional Effects of Active Site Mutations in NAD+-Dependent Formate Dehydrogenases on Transformation of Hydrogen Carbonate to Formate. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2018, 31, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phintha, A.; Chaiyen, P. Rational and Mechanistic Approaches for Improving Biocatalyst Performance. Chem Catal. 2022, 2, 2614–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Li, J.; Shin, H.D.; Chen, R.R.; Du, G.; Liu, L.; Chen, J. Recent Advances in Discovery, Heterologous Expression, and Molecular Engineering of Cyclodextrin Glycosyltransferase for Versatile Applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, N.M.; Gosavi, S. Understanding Protein Domain-Swapping Using Structure-Based Models of Protein Folding. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2016, 128, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merz, A.; Yee, M.C.; Szadkowski, H.; Pappenberger, G.; Crameri, A.; Stemmer, W.P.C.; Yanofsky, C.; Kirschner, K. Improving the Catalytic Activity of a Thermophilic Enzyme at Low Temperatures. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joho, Y.; Vongsouthi, V.; Gomez, C.; Larsen, J.S.; Ardevol, A.; Jackson, C.J. Improving Plastic Degrading Enzymes via Directed Evolution. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2024, 37, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, S.; Soumillion, P. Directed Evolution for Enzyme Development in Biocatalysis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 61, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, F.H. Innovation by Evolution: Bringing New Chemistry to Life (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 14420–14426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xue, P.; Cao, M.; Yu, T.; Lane, S.T.; Zhao, H. Directed Evolution: Methodologies and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12384–12444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, A.; Arzumanyan, G.A.; Obadi, M.K.A.; Javanpour, A.A.; Liu, C.C. Scalable, Continuous Evolution of Genes at Mutation Rates above Genomic Error Thresholds. Cell 2018, 175, 1946–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakzad, H.; Igashov, I.; Schneuing, A.; Goverde, C.; Bronstein, M.; Correia, B. A New Age in Protein Design Empowered by Deep Learning. Cell Syst. 2023, 14, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauparas, J.; Anishchenko, I.; Bennett, N.; Bai, H.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; Wicky, B.I.M.; Courbet, A.; de Haas, R.J.; Bethel, N.; et al. Robust Deep Learning–Based Protein Sequence Design Using ProteinMPNN. Science 2022, 378, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumulya, Y.; Gillam, E.M.J. Exploring the Past and the Future of Protein Evolution with Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction: The ‘Retro’ Approach to Protein Engineering. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochberg, G.K.A.; Thornton, J.W. Reconstructing Ancient Proteins to Understand the Causes of Structure and Function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2017, 46, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genetic Engineering. Available online: https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Genetic-Engineering (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Knott, G.J.; Doudna, J.A. CRISPR-Cas Guides the Future of Genetic Engineering. Science 2018, 361, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Wei, C.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.E.; Wei, H. Construction of a Chimeric Lysin Ply187N-V12C with Extended Lytic Activity against Staphylococci and Streptococci. Microb. Biotechnol. 2015, 8, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanova, L.; Golotin, V.; Kovalchuk, S.; Bulgakov, A.; Likhatskaya, G.; Son, O.; Rasskazov, V. A Novel Bifunctional Hybrid with Marine Bacterium Alkaline Phosphatase and Far Eastern Holothurian Mannan-Binding Lectin Activities. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheybi, E.; Amani, J.; Salmanian, A.H.; Mashayekhi, F.; Khodi, S. Designing a Recombinant Chimeric Construct Contain MUC1 and HER2 Extracellular Domain for Prediagnostic Breast Cancer. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 11489–11497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, R.; Imai, S.; Murata, T.; Nomura, Y.; Okamoto, M.; Tsumori, H.; Kakuta, E.; Hanada, N.; Momoi, Y. Application of Chimeric Glucanase Comprising Mutanase and Dextranase for Prevention of Dental Biofilm Formation. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 59, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.A.; Venu, K.; Rao, D.E.C.S.; Rao, K.V.; Reddy, V.D. Chimeric Gene Construct Coding for Bi-Functional Enzyme Endowed with Endoglucanase and Phytase Activities. Arch. Microbiol. 2009, 191, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, T.; Yasutake, Y.; Nishiya, Y.; Tamura, T. Structure-Guided Mutagenesis for the Improvement of Substrate Specificity of Bacillus Megaterium Glucose 1-Dehydrogenase IV. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 3264–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Cui, W.; Ding, N.; Liu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, Z. Structure-Based Approach to Alter the Substrate Specificity of Bacillus Subtilis Aminopeptidase. Prion 2013, 7, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Webster, C.I.; Burrell, M.; Olsson, L.L.; Fowler, S.B.; Digby, S.; Sandercock, A.; Snijder, A.; Tebbe, J.; Haupts, U.; Grudzinska, J.; et al. Engineering Neprilysin Activity and Specificity to Create a Novel Therapeutic for Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umekawa, M.; Li, C.; Higashiyama, T.; Huang, W.; Ashida, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Wang, L.X. Efficient Glycosynthase Mutant Derived from Mucor Hiemalis Endo-β-N-Acetylglucosaminidase Capable of Transferring Oligosaccharide from Both Sugar Oxazoline and Natural N-Glycan. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hediger, M.R.; De Vico, L.; Rannes, J.B.; Jäckel, C.; Besenmatter, W.; Svendsen, A.; Jensen, J.H. In Silico Screening of 393 Mutants Facilitates Enzyme Engineering of Amidase Activity in CalB. PeerJ 2013, 2013, e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.A.; Whitneye, D.S.; Volkmane, B.F.; Doe, C.Q.; Prehoda, K.E. Conversion of the Enzyme Guanylate Kinase into a Mitotic-Spindle Orienting Protein by a Single Mutation That Inhibits GMP-Induced Closing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, E973–E978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, C.L.; Jarrett, J.T. From Single Molecules to Whole Organisms: The Evolving Field of Mechanistic Enzymology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009, 13, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Holdgate, G.A.; Meek, T.D.; Grimley, R.L. Mechanistic Enzymology in Drug Discovery: A Fresh Perspective. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Perez-Ortiz, G.; Peate, J.; Barry, S.M. Redesigning Enzymes for Biocatalysis: Exploiting Structural Understanding for Improved Selectivity. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 908285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, C.K.; Schrittwieser, J.H.; Kroutil, W. Power of Biocatalysis for Organic Synthesis. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyser, J.B.; Chakrabarty, S.; Romero, E.O.; Narayan, A.R.H. State-of-the-Art Biocatalysis. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruice, T.C.; Benkovic, S.J. Chemical Basis for Enzyme Catalysis. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 6267–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warshel, A.; Sharma, P.K.; Kato, M.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, H.; Olsson, M.H.M. Electrostatic Basis for Enzyme Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 3210–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

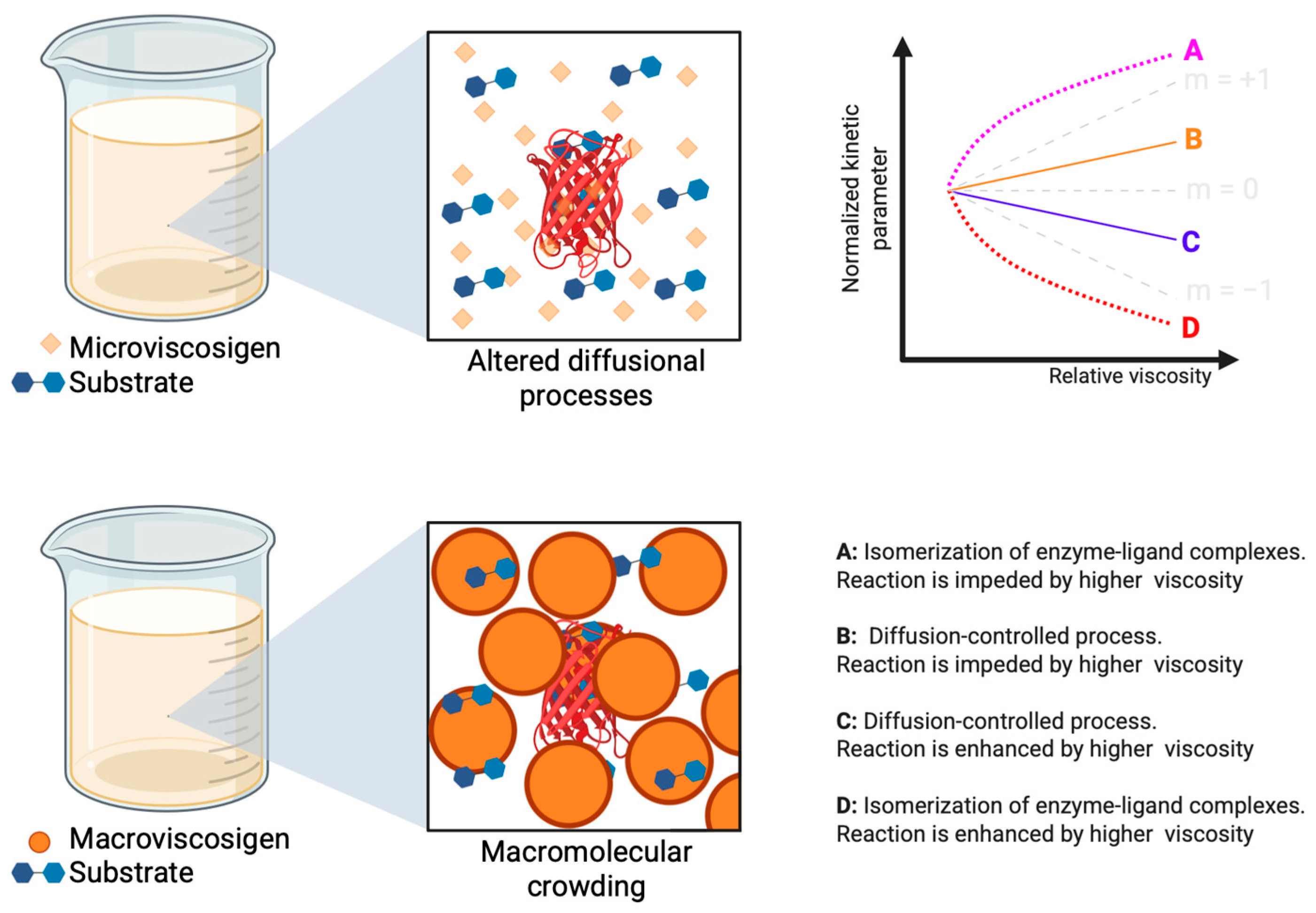

- Gadda, G.; Sobrado, P. Kinetic Solvent Viscosity Effects as Probes for Studying the Mechanisms of Enzyme Action. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 3445–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.; Franceschini, S.; Fedkenheuer, M.; Rodriguez, P.J.; Ellerbrock, J.; Romero, E.; Echandi, M.P.; Martin Del Campo, J.S.; Sobrado, P. Arg279 Is the Key Regulator of Coenzyme Selectivity in the Flavin-Dependent Ornithine Monooxygenase SidA. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Proteins Proteom. 2014, 1844, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Fonseca, I.; Qureshi, I.A.; Mehra-Chaudhary, R.; Kizjakina, K.; Tanner, J.J.; Sobrado, P. Contributions of Unique Active Site Residues of Eukaryotic UDP-Galactopyranose Mutases to Substrate Recognition and Active Site Dynamics. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moni, B.M.; Quaye, J.A.; Gadda, G. Mutation of a Distal Gating Residue Modulates NADH Binding in NADH:Quinone Oxidoreductase from Pseudomonas Aeruginosa PAO1. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 103044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.R.; Benkovic, S.J. Site Directed Mutagenesis: A Tool for Enzyme Mechanism Dissection. Trends Biotechnol. 1990, 8, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunden, F.; Peck, A.; Salzman, J.; Ressl, S.; Herschlag, D. Extensive Site-Directed Mutagenesis Reveals Interconnected Functional Units in the Alkaline Phosphatase Active Site. Elife 2015, 4, e06181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramers, H.A. Brownian Motion in a Field of Force and the Diffusion Model of Chemical Reactions. Physica 1940, 7, 284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, J.A.; Gadda, G. The Pseudomonas Aeruginosa PAO1 Metallo Flavoprotein D-2-Hydroxyglutarate Dehydrogenase Requires Zn2+ for Substrate Orientation and Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 103008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, J.A.; Ball, J.; Gadda, G. Kinetic Solvent Viscosity Effects Uncover an Internal Isomerization of the Enzyme-Substrate Complex in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa PAO1 NADH:Quinone Oxidoreductase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 727, 109342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodovoz, M.; Gadda, G. Kinetic Solvent Viscosity Effects Reveal a Protein Isomerization in the Reductive Half-Reaction of Neurospora Crassa Class II Nitronate Monooxygenase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 695, 108625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achuthan, S.; Chung, B.J.; Ghosh, P.; Rangachari, V.; Vaidya, A. A Modified Stokes-Einstein Equation for Aβ Aggregation. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, S.; Sampedro, J.G. Measuring Solution Viscosity and Its Effect on Enzyme Activity. Biol. Proced. Online 2003, 5, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, W.W. Partition Analysis and the Concept of Net Rate Constants as Tools in Enzyme Kinetics. Biochemistry 1975, 14, 3220–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, P.F.; Kurtz, K.A.; Denu, J.M.; Emanuele, J.F. Contrasting Values of Commitment Factors Measured from Viscosity, PH, and Kinetic Isotope Effects: Evidence for Slow Conformational Changes in TheD-Amino Acid Oxidase Reaction. Bioorg. Chem. 1997, 25, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, A.W. A New Method of X-Ray Crystal Analysis. Phys. Rev. 1917, 10, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleva, E.G.; Lipscomb, J.D. Crystal Structures of Fe2+ Dioxygenase Superoxo, Alkylperoxo, and Bound Product Intermediates. Science 2007, 316, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra-Chaudhary, R.; Dai, Y.; Sobrado, P.; Tanner, J.J. In Crystallo Capture of a Covalent Intermediate in the UDP-Galactopyranose Mutase Reaction. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 833–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, D.D. Hydrogen Exchange Mass Spectrometry of Proteins; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Masson, G.R.; Burke, J.E.; Ahn, N.G.; Anand, G.S.; Borchers, C.; Brier, S.; Bou-Assaf, G.M.; Engen, J.R.; Englander, S.W.; Faber, J.; et al. Recommendations for Performing, Interpreting and Reporting Hydrogen Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) Experiments. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, E.A.; Benhaim, M.A.; Lee, K.K. Bridging Protein Structure, Dynamics, and Function Using Hydrogen/Deuterium-Exchange Mass Spectrometry. Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.A.; Engen, J.R. Conformational Insight into Multi-Protein Signaling Assemblies by Hydrogen–Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016, 41, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadas, O.; Jenkins, M.L.; Dornan, G.L.; Burke, J.E. Using Hydrogen–Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry to Examine Protein–Membrane Interactions. Methods Enzym. 2017, 583, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englander, S.W.; Mayne, L. The Nature of Protein Folding Pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15873–15880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Kalodimos, C.G. NMR Studies of Large Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenzweig, R.; Kay, L.E. Bringing Dynamic Molecular Machines into Focus by Methyl-TROSY NMR. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014, 83, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bugge, K.; Kragelund, B.B.; Lindorff-Larsen, K. Role of Protein Dynamics in Transmembrane Receptor Signalling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018, 48, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, A.K. Solid-State NMR Approaches to Investigate Large Enzymes in Complex with Substrates and Inhibitors. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2021, 49, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, N.E.; Paul, J.; Malthouse, G.; Scott, A.I. Studying Enzyme Mechanism by 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Science 1984, 225, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A. Advances in Transient-State Kinetics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 1998, 9, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.S.; Sammons, R.D.; Leo, G.C.; Sikorski, J.A.; Benesi, A.J.; Johnson, K.A. Observation by 13C NMR of the EPSP Synthase Tetrahedral Intermediate Bound to the Enzyme Active Site. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 1460–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.S.; Johnson, K.A. “Kinetic Competence” of the 5-Enolpyruvoylshikimate-3-Phosphate Synthase Tetrahedral Intermediate*. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 5567–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleyard, R. Direct Observation of the Enzyme-Intermediate Complex of 5-Enolpyruvylshikimate-3-Phosphate Synthase by Carbon-13 NMR Spectroscopy. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 7985–7991. [Google Scholar]

- Studelska, D.R.; McDowell, L.M.; Espe, M.P.; Klug, C.A.; Schaefer, J. Slowed Enzymatic Turnover Allows Characterization of Intermediates by Solid-State NMR. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 15555–15560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.A. Transient State Enzyme Kinetics. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Chemical Biology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, H.F. Transient-State Kinetic Approach to Mechanisms of Enzymatic Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005, 38, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Campbell, C.T. Kinetic Isotope Effects: Interpretation and Prediction Using Degrees of Rate Control. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 4181–4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkes, E.L.; Studt, F.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Schlögl, R.; Behrens, M. Hydrogenation of CO2 to Methanol and CO on Cu/ZnO/Al2O3: Is There a Common Intermediate or Not? J. Catal. 2015, 328, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Iglesia, E. Isotopic and Kinetic Assessment of the Mechanism of Reactions of CH4 with CO2 or H2O to Form Synthesis Gas and Carbon on Nickel Catalysts. J. Catal. 2004, 224, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, M.; Li, A.; Nabar, R.; Nilekar, A.U.; Mavrikakis, M.; Iglesia, E. Kinetically Relevant Steps and H2/D2 Isotope Effects in Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis on Fe and Co Catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 19761–19770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, W.W. The Use of Isotope Effects to Determine Enzyme Mechanisms. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005, 433, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, F.; Rodriguez, I.; Hamelberg, D.; Gadda, G. Role of F357 as an Oxygen Gate in the Oxidative Half-Reaction of Choline Oxidase. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepankova, V.; Bidmanova, S.; Koudelakova, T.; Prokop, Z.; Chaloupkova, R.; Damborsky, J. Strategies for Stabilization of Enzymes in Organic Solvents. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 2823–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pätzold, M.; Siebenhaller, S.; Kara, S.; Liese, A.; Syldatk, C.; Holtmann, D. Deep Eutectic Solvents as Efficient Solvents in Biocatalysis. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 943–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrea, G.; Riva, S. Properties and Synthetic Applications of Enzymes in Organic Solvents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 2226–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.M.; Gilman, J.W.; Morgan, A.B.; Shields, J.R.; Maupin, P.H.; Lyon, R.E.; De Long, H.C.; Trulove, P.C. Flammability and Thermal Analysis Characterization of Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 6327–6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emel’Yanenko, V.N.; Boeck, G.; Verevkin, S.P.; Ludwig, R. Volatile Times for the Very First Ionic Liquid: Understanding the Vapor Pressures and Enthalpies of Vaporization of Ethylammonium Nitrate. Chem.–A Eur. J. 2014, 20, 11640–11645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maton, C.; De Vos, N.; Stevens, C.V. Ionic liquid thermal stabilities: Decomposition mechanisms and analysis tools. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5963–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meine, N.; Benedito, F.; Chemistry, R.R.-G. Thermal stability of ionic liquids assessed by potentiometric titration. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1711–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chícharo, B.; Cuesta, M.; Trapasso, G.; Porcar, R.; Martín, N.; Villa, R.; Lozano, P.; Fadlallah, S.; Allais, F.; García-Verdugo, E.; et al. Chemical and Enzymatic Synthetic Routes to the Diglycidyl Ester of 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 46, 102101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K.; Tambyrajah, V. Novel Solvent Properties of Choline Chloride/Urea Mixtures. Chem. Commun. 2003, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysokowski, M.; Luu, R.K.; Arevalo, S.; Khare, E.; Stachowiak, W.; Niemczak, M.; Jesionowski, T.; Buehler, M.J. Untapped Potential of Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Synthesis of Bioinspired Inorganic–Organic Materials. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 7878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, B.B.; Spittle, S.; Chen, B.; Poe, D.; Zhang, Y.; Klein, J.M.; Horton, A.; Adhikari, L.; Zelovich, T.; Doherty, B.W.; et al. Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review of Fundamentals and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1232–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, C.; He, Y.C. Chemobiocatalytic Transfromation of Biomass into Furfurylamine with Mixed Amine Donor in an Eco-Friendly Medium. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 387, 129638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peito, S.; Peixoto, D.; Ferreira-Faria, I.; Margarida Martins, A.; Margarida Ribeiro, H.; Veiga, F.; Marto, J.; Cláudia Paiva-Santos, A. Nano- and Microparticle-Stabilized Pickering Emulsions Designed for Topical Therapeutics and Cosmetic Applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 615, 121455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.C.; Pan, T.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Z. Oil–Water Interfaces of Pickering Emulsions: Microhabitats for Living Cell Biocatalysis. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, K.A.; Sadeghi, R. Database of Deep Eutectic Solvents and Their Physical Properties: A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 384, 121899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruß, C.; König, B. Low Melting Mixtures in Organic Synthesis—An Alternative to Ionic Liquids? Green Chem. 2012, 14, 2969–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmad, S.; Xie, Y.; Mikkola, J.P.; Ji, X. Screening of Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) as Green CO2 Sorbents: From Solubility to Viscosity. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, K.; Mjalli, F.S.; Hashim, M.A.; AlNashef, I.M. Prediction of the Surface Tension of Deep Eutectic Solvents. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2012, 319, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagh, F.S.G.; Shahbaz, K.; Mjalli, F.S.; AlNashef, I.M.; Hashim, M.A. Electrical Conductivity of Ammonium and Phosphonium Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: Measurements and Artificial Intelligence-Based Prediction. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2013, 356, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjalli, F.S.; Naser, J.; Jibril, B.; Alizadeh, V.; Gano, Z. Tetrabutylammonium Chloride Based Ionic Liquid Analogues and Their Physical Properties. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2014, 59, 2242–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, J.; Mjalli, F.S.; Gano, Z.S. Molar Heat Capacity of Selected Type III Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2016, 61, 1608–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjalli, F.S.; Naser, J. Viscosity Model for Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 10, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibril, B.; Mjalli, F.; Naser, J.; Gano, Z. New Tetrapropylammonium Bromide-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: Synthesis and Characterizations. J. Mol. Liq. 2014, 199, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ludwig, M.; Warr, G.G.; Atkin, R. Effect of Cation Alkyl Chain Length on Surface Forces and Physical Properties in Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 494, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdarta, J.; Jesionowski, T.; Pinelo, M.; Meyer, A.S.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Bilal, M.; Nguyen, L.N.; Nghiem, L.D. Free and Immobilized Biocatalysts for Removing Micropollutants from Water and Wastewater: Recent Progress and Challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdarta, J.; Meyer, A.S.; Jesionowski, T.; Pinelo, M. A General Overview of Support Materials for Enzyme Immobilization: Characteristics, Properties, Practical Utility. Catalysts 2018, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, P.; Kamala-Kannan, S.; Cho, M.; Kim, J.S.; Hadibarata, T.; Salim, M.R.; Oh, B.-T. Laccase Immobilization on Cellulose Nanofiber: The Catalytic Efficiency and Recyclic Application for Simulated Dye Effluent Treatment. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzymatic 2014, 100, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheran, M.; Naghdi, M.; Brar, S.; Knystautas, E.; Verma, M.; Surampalli, R. Degradation of Chlortetracycline Using Immobilized Laccase on Polyacrylonitrile-Biochar Composite Nanofibrous Membrane. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 605-606, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, G.E.; Haldane, J.B.S. A Note on the Kinetics of Enzyme Action. Biochem. J. 1925, 19, 338–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, W.W. 3 Steady-State Kinetics. Enzymes 1990, 19, 99–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorsch, J.R. Practical Steady-State Enzyme Kinetics. Methods Enzym. 2014, 536, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgharbawy, A.A.; Riyadi, F.A.; Alam, M.Z.; Moniruzzaman, M. Ionic Liquids as a Potential Solvent for Lipase-Catalysed Reactions: A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 251, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A. Kinetic Analysis for the New Enzymology: Using Computer Simulation to Learn Kinetics and Solve Mechanisms; KinTek Corp.: Snow Shoe, PA, USA, 2019; Volume 480. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, J. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, 4th ed.; Nelson, D., Cox, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Bognor Regis, UK, 2005; Volume 33, ISBN 0716743396. [Google Scholar]

- Hermes, J.D.; Roeske, C.A.; O’Leary, M.H.; Cleland, W.W. Use of Multiple Isotope Effects to Determine Enzyme Mechanisms and Intrinsic Isotope Effects. Malic Enzyme and Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 1982, 21, 5106–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, E.D.; Shimada, H.; Kovrigin, E.L.; Loria, J.P. The Mechanism of Rate-Limiting Motions in Enzyme Function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 11981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfenden, R.; Snider, M.J. The Depth of Chemical Time and the Power of Enzymes as Catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, K.M.; Hampel, K.J. A Rate-Limiting Conformational Step in the Catalytic Pathway of the GlmS Ribozyme. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 5669–5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C. Visual Interpretation of the Meaning of Kcat/KMin Enzyme Kinetics. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 2556–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A. New Standards for Collecting and Fitting Steady State Kinetic Data. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krooshof, G.H.; Kwant, E.M.; Damborský, J.; Koča, J.; Janssen, D.B. Repositioning the Catalytic Triad Aspartic Acid of Haloalkane Dehalogenase: Effects on Stability, Kinetics, and Structure. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 9571–9580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafaga, D.S.R.; Muteeb, G.; Elgarawany, A.; Aatif, M.; Farhan, M.; Allam, S.; Almatar, B.A.; Radwan, M.G. Green Nanobiocatalysts: Enhancing Enzyme Immobilization for Industrial and Biomedical Applications. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Lei, J.; Zare, R.N. Protein–Inorganic Hybrid Nanoflowers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Kong, W.; Qiao, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z. Visible-Light-Induced Effects of Au Nanoparticle on Laccase Catalytic Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 20937–20944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, X.; Gao, F.; Peng, M.; He, Y.; Fan, H. Recent Advances in Enzyme-Nanostructure Biocatalysts with Enhanced Activity. Catalysts 2020, 10, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Liu, A. Novel Cell–Inorganic Hybrid Catalytic Interfaces with Enhanced Enzymatic Activity and Stability for Sensitive Biosensing of Paraoxon. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 6894–6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holyavka, M.G.; Goncharova, S.S.; Redko, Y.A.; Lavlinskaya, M.S.; Sorokin, A.V.; Artyukhov, V.G. Novel Biocatalysts Based on Enzymes in Complexes with Nano- and Micromaterials. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezovsky, J.; Babkova, P.; Degtjarik, O.; Fortova, A.; Gora, A.; Iermak, I.; Rezacova, P.; Dvorak, P.; Smatanova, I.K.; Prokop, Z.; et al. Engineering a de Novo Transport Tunnel. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7597–7610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedermannová, L.; Prokop, Z.; Gora, A.; Chovancová, E.; Kovács, M.; Damborský, J.; Wade, R.C. A Single Mutation in a Tunnel to the Active Site Changes the Mechanism and Kinetics of Product Release in Haloalkane Dehalogenase LinB. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 29062–29074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klvana, M.; Pavlova, M.; Koudelakova, T.; Chaloupkova, R.; Dvorak, P.; Prokop, Z.; Stsiapanava, A.; Kuty, M.; Kuta-Smatanova, I.; Dohnalek, J.; et al. Pathways and Mechanisms for Product Release in the Engineered Haloalkane Dehalogenases Explored Using Classical and Random Acceleration Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 392, 1339–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardar, G.; Wood, T.K. Alpha-Subunit Positions Methionine 180 and Glutamate 214 of Pseudomonas Stutzeri OX1 Toluene-o-Xylene Monooxygenase Influence Catalysis. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 1511–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zheng, F.; Tu, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, R.; Su, X.; Xie, X.; Yao, B.; Luo, H. Enhancing the Catalytic Activity of a Novel GH5 Cellulase GtCel5 from Gloeophyllum Trabeum CBS 900.73 by Site-Directed Mutagenesis on Loop 6. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, A.E.; Pedroso, M.M.; Chappell, K.J.; Watterson, D.; Liebscher, S.; Kok, W.M.; Fairlie, D.P.; Schenk, G.; Young, P.R. Product Release Is Rate-Limiting for Catalytic Processing by the Dengue Virus Protease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyen, D.; Fenwick, R.B.; Stanfield, R.L.; Dyson, H.J.; Wright, P.E. Cofactor-Mediated Conformational Dynamics Promote Product Release from Escherichia Coli Dihydrofolate Reductase via an Allosteric Pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9459–9468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyen, D.; Bryn Fenwick, R.; Aoto, P.C.; Stanfield, R.L.; Wilson, I.A.; Jane Dyson, H.; Wright, P.E. Defining the Structural Basis for Allosteric Product Release from E. Coli Dihydrofolate Reductase Using NMR Relaxation Dispersion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 11233–11240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoma, N.H.; Iakovenko, A.; Kalinin, A.; Waldmann, H.; Goody, R.S.; Alexandrov, K. Allosteric Regulation of Substrate Binding and Product Release in Geranylgeranyltransferase Type II. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.W.; Oh, E.; Hastman, D.A.; Walper, S.A.; Susumu, K.; Stewart, M.H.; Deschamps, J.R.; Medintz, I.L. Kinetic Enhancement of the Diffusion-Limited Enzyme Beta-Galactosidase When Displayed with Quantum Dots. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 93089–93094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breger, J.C.; Ancona, M.G.; Walper, S.A.; Oh, E.; Susumu, K.; Stewart, M.H.; Deschamps, J.R.; Medintz, I.L. Understanding How Nanoparticle Attachment Enhances Phosphotriesterase Kinetic Efficiency. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 8491–8503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malanoski, A.P.; Breger, J.C.; Brown, C.W.; Deschamps, J.R.; Susumu, K.; Oh, E.; Anderson, G.P.; Walper, S.A.; Medintz, I.L. Kinetic Enhancement in High-Activity Enzyme Complexes Attached to Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Horiz. 2017, 2, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cao, K.; Pedroso, M.M.; Wu, B.; Gao, Z.; He, B.; Schenk, G. Sequence- And Structure-Guided Improvement of the Catalytic Performance of a GH11 Family Xylanase from Bacillus Subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryanova, B.; Goldman, L.M.; Ming, S.; Amyes, T.L.; Gerlt, J.A.; Richard, J.P. Rate and Equilibrium Constants for an Enzyme Conformational Change during Catalysis by Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 4555–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duff, M.R.; Redzic, J.S.; Ryan, L.P.; Paukovich, N.; Zhao, R.; Nix, J.C.; Pitts, T.M.; Agarwal, P.; Eisenmesser, E.Z. Structure, Dynamics and Function of the Evolutionarily Changing Biliverdin Reductase B Family. J. Biochem. 2020, 168, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamnevik, E.; Enugala, T.R.; Maurer, D.; Ntuku, S.; Oliveira, A.; Dobritzsch, D.; Widersten, M. Relaxation of Nonproductive Binding and Increased Rate of Coenzyme Release in an Alcohol Dehydrogenase Increases Turnover with a Nonpreferred Alcohol Enantiomer. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 3895–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blikstad, C.; Dahlström, K.M.; Salminen, T.A.; Widersten, M. Substrate Scope and Selectivity in Offspring to an Enzyme Subjected to Directed Evolution. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 2387–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwumba, I.N.; Ozawa, K.; Xu, Z.Q.; Ely, F.; Foo, J.L.; Herlt, A.J.; Coppin, C.; Brown, S.; Taylor, M.C.; Ollis, D.L.; et al. Improving a Natural Enzyme Activity through Incorporation of Unnatural Amino Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckelynck, M.; Baudrey, S.; Rick, C.; Marin, A.; Coldren, F.; Westhof, E.; Griffiths, A.D. Using Droplet-Based Microfluidics to Improve the Catalytic Properties of RNA under Multiple-Turnover Conditions. RNA 2015, 21, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Chen, C.; Wang, T.; Huang, A.; Zhang, D.; Han, M.J.; Wang, J. Genetic Incorporation of Selenotyrosine Significantly Improves Enzymatic Activity of Agrobacterium Radiobacter Phosphotriesterase. Chembiochem 2021, 22, 2535–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, J.A.; Ouedraogo, D.; Gadda, G. Targeted Mutation of a Non-Catalytic Gating Residue Increases the Rate of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa d-Arginine Dehydrogenase Catalytic Turnover. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 17343–17352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Dong, W.; Lu, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, X. Simultaneously Enhanced Thermostability and Catalytic Activity of Xylanase from Streptomyces Rameus L2001 by Rigidifying Flexible Regions in Loop Regions of the N-Terminus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 12785–12796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Kyeong, H.H.; Choi, J.M.; Sohn, Y.K.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.S. Engineering of the Conformational Dynamics of an Enzyme for Relieving the Product Inhibition. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 8440–8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, M.; Klvana, M.; Prokop, Z.; Chaloupkova, R.; Banas, P.; Otyepka, M.; Wade, R.C.; Tsuda, M.; Nagata, Y.; Damborsky, J. Redesigning Dehalogenase Access Tunnels as a Strategy for Degrading an Anthropogenic Substrate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.; Wang, J.; Shi, T.; Zhao, Y.; Ouyang, P.; Chen, K. Engineering of Lysine Cyclodeaminase Conformational Dynamics for Relieving Substrate and Product Inhibitions in the Biosynthesis of L-Pipecolic Acid. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.N.; Conrath, K.; Steyaert, J. Substrate-Dependent Modulation of Enzyme Activity by Allosteric Effector Antibodies. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2009, 1794, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, A.P.C.A.; Almeida, P.C.; Tersariol, I.L.S.; Schmitz, V.; Schmaier, A.H.; Juliano, L.; Hirata, I.Y.; Müller-Esterl, W.; Chagas, J.R.; Scharfstein, J. Heparan Sulfate Modulates Kinin Release by Trypanosoma Cruzi through the Activity of Cruzipain. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 5875–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röthlisberger, D.; Khersonsky, O.; Wollacott, A.M.; Jiang, L.; DeChancie, J.; Betker, J.; Gallaher, J.L.; Althoff, E.A.; Zanghellini, A.; Dym, O.; et al. Kemp Elimination Catalysts by Computational Enzyme Design. Nature 2008, 453, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Althoff, E.A.; Clemente, F.R.; Doyle, L.; Röthlisberger, D.; Zanghellini, A.; Gallaher, J.L.; Betker, J.L.; Tanaka, F.; Barbas, C.F.; et al. De Novo Computational Design of Retro-Aldol Enzymes. Science 2008, 319, 1387–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A.J.; Lovelock, S.L.; Frese, A.; Crawshaw, R.; Ortmayer, M.; Dunstan, M.; Levy, C.; Green, A.P. Design and Evolution of an Enzyme with a Non-Canonical Organocatalytic Mechanism. Nature 2019, 570, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Ye, L.; Yang, X.; Wang, B.; Yang, C.; Gu, J.; Yu, H. Reconstruction of the Catalytic Pocket and Enzyme–Substrate Interactions to Enhance the Catalytic Efficiency of a Short-Chain Dehydrogenase/Reductase. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 3229–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J.B.; Zanghellini, A.; Lovick, H.M.; Kiss, G.; Lambert, A.R.; St.Clair, J.L.; Gallaher, J.L.; Hilvert, D.; Gelb, M.H.; Stoddard, B.L.; et al. Computational Design of an Enzyme Catalyst for a Stereoselective Bimolecular Diels-Alder Reaction. Science 2010, 329, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obexer, R.; Godina, A.; Garrabou, X.; Mittl, P.R.E.; Baker, D.; Griffiths, A.D.; Hilvert, D. Emergence of a Catalytic Tetrad during Evolution of a Highly Active Artificial Aldolase. Nat. Chem. 2016, 9, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, H.C.; Dalby, P.A. Fine-Tuning the Activity and Stability of an Evolved Enzyme Active-Site through Noncanonical Amino-Acids. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 1935–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarzadeh, A.; Pourzardosht, N.; Dehnavi, E.; Ranaei Siadat, S.O.; Zamani, M.R.; Motallebi, M.; Nikzad Jamnani, F.; Aghaeepoor, M.; Barshan Tashnizi, M. Disulfide Bonds Elimination of Endoglucanase II from Trichoderma Reesei by Site-Directed Mutagenesis to Improve Enzyme Activity and Thermal Stability: An Experimental and Theoretical Approach. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2018, 120, 1572–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, Y. Improving Catalytic Efficiency and Changing Substrate Spectrum for Asymmetric Biocatalytic Reductive Amination. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 30, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, H.; Hwang, B.J.; Choi, D.Y.; Shin, S.; Choi, M. Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) Protease with Multiple Mutations to Improve Solubility and Reduce Self-Cleavage Exhibits Enhanced Enzymatic Activity. FEBS Open Bio 2020, 10, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić Đurđić, K.; Ostafe, R.; Prodanović, O.; Đurđević Đelmaš, A.; Popović, N.; Fischer, R.; Schillberg, S.; Prodanović, R. Improved Degradation of Azo Dyes by Lignin Peroxidase Following Mutagenesis at Two Sites near the Catalytic Pocket and the Application of Peroxidase-Coated Yeast Cell Walls. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2021, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Yao, Q.; Yu, G.; Liu, S.; Yun, J.; Xiao, X.; Deng, Z.; Li, H. Biochemical Characterization of a Novel Bacterial Laccase and Improvement of Its Efficiency by Directed Evolution on Dye Degradation. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 633004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Cheng, F.; Piatkowski, V.; Schwaneberg, U. Protein Engineering of the Antitumor Enzyme PpADI for Improved Thermal Resistance. ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Tan, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wu, G.; Shao, Y.; Wang, M.; Song, Z.; Xin, Z. Improving the Activity and Expression Level of a Phthalate-Degrading Enzyme by a Combination of Mutagenesis Strategies and Strong Promoter Replacement. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 41107–41119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.G.; Xue, Y.; Lu, Z.P.; Xu, H.J.; Hu, Y. Chemical Modification for Improving Catalytic Performance of Lipase B from Candida Antarctica with Hydrophobic Proline Ionic Liquid. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 45, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Q.; Yin, H.H.; Zhang, X.J.; Zhou, R.; Wang, Y.M.; Zheng, Y.G. Improvement of Carbonyl Reductase Activity for the Bioproduction of Tert-Butyl (3R, 5S)-6-Chloro-3, 5-Dihydroxyhexanoate. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 80, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Chen, C.C.; Huang, J.W.; Ko, T.P.; Huang, Z.; Guo, R.T. Improving the Catalytic Performance of a GH11 Xylanase by Rational Protein Engineering. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 9503–9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voet, D.; Voet, J.G.; Pratt, C.W. Principles of Biochemistry, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 0470233966. [Google Scholar]

- Northrop, D.B.; Scovell, W.M. On the Meaning of Km and V/K in Enzyme Kinetics. J. Chem. Educ. 1998, 75, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sheng, Y.; Cui, H.; Qiao, J.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, H. Corner Engineering: Tailoring Enzymes for Enhanced Resistance and Thermostability in Deep Eutectic Solvents. Angew. Chem. 2024, 136, e202315125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranaei Siadat, S.O.; Mollasalehi, H.; Heydarzadeh, N. Substrate Affinity and Catalytic Efficiency Are Improved by Decreasing Glycosylation Sites in Trichoderma Reesei Cellobiohydrolase I Expressed in Pichia Pastoris. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhu, R.; Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Hu, N. Improving the Catalytic Efficiency and Substrate Affinity of a Novel Esterase from Marine Klebsiella Aerogenes by Random and Site-Directed Mutation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B.; Du, G.; Chen, J. Enhancement of the Catalytic Efficiency and Thermostability of Stenotrophomonas Sp. Keratinase KerSMD by Domain Exchange with KerSMF. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Lin, J.; Chen, F. Focused Mutagenesis in Non-Catalytic Cavity for Improving Catalytic Efficiency of 3-Ketosteroid-Δ1-Dehydrogenase. Mol. Catal. 2022, 531, 112661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ma, T.; Shang-guan, F.; Han, Z. Improving the Catalytic Activity of Thermostable Xylanase from Thermotoga Maritima via Mutagenesis of Non-Catalytic Residues at Glycone Subsites. Enzyme. Microb. Technol. 2020, 139, 109579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Song, W.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Luo, Q.; Liu, L. Production of α-Ketoisocaproate and α-Keto-β-Methylvalerate by Engineered L-Amino Acid Deaminase. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 2464–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesbah, N.M. Industrial Biotechnology Based on Enzymes from Extreme Environments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 870083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Protein | Major Structural Characteristic | Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriophage lysine, Ply187N-V12C | Catalytic domain of Ply187 lysin; bacterial cell-binding domain of PlyV12 lysin | Enhanced antimicrobial therapy due to an increase in lytic activity against human pathogens | [30] |

| Tumor-associated antigens MUC1 and HER2 | MUC1subunit; HER2 subunit | Enhanced breast cancer detection in ELISA against MUC1 or HER2 | [32] |

| α-Glucanohydrolase, mut-dexA | N-terminal mutanase domain; C-terminal dextranase domain | Enhanced α-glucan hydrolysis in fighting dental biofilm formation | [33] |

| Bacillus subtilis phytase | N-terminal β-1,4 endoglucanase domain; C-terminal phytase domain | Enhanced nutrition uptake as a potential feed additive for monogastric animals | [34] |

| Glucose 1-dehydrogenase IV, BmGlcDH-IV | Mutation G259A | Altered substrate specificity to exclusively D-glucose for clinical testing of blood glucose levels | [35] |

| Bacillus subtilis aminopeptidase, BSAP | Mutations I387A, I387C and I387S | Modified substrate specificity to enable hydrolysis of phenylalanine derivatives with bulky side chains | [36] |

| Transmembrane zinc metallopeptidase Neprilysin, NEP | Mutations G399V/G714K | Altered protein cleavage site specificity to target the Phe20-Ala21 bond in amyloid β 1-40 for Alzheimer’s disease treatment | [37] |

| Mucor hiemalis endo-b-N-acetylglucosaminidase, Endo-M | Mutation N175Q | Enhanced glycosynthase activity with oxazoline and natural N glycan for the synthesis of glycoproteins | [38] |

| Candida antarctica lipase B, CalB | Mutations G39A, T103G, W104F, A141Q, I189Y, L278A | Increasing amidase activity to three times that of the wild type for the production of optically active amines | [39] |

| Guanylate kinase (GK) | Mutation S68P | Altering GK function from enzymatic activity to protein-binding to regulate mitotic spindle orientation and cell adhesion | [40] |

| Microviscosigen | Macroviscosigen | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MW (Da) | Typical MW Range (kDa) | ||

| Glucose | 180.2 | Polyethylene glycol | 200–20,000 |

| Sucrose | 342.3 | Polyacrylamide | Varies, reaching several millions |

| Glycerol | 92.1 | Ficoll | 300–700 |

| Ethylene glycol | 62.1 | Dextran | 40–500 |

| Trehalose | 342.3 | Polyethylene oxide | 100–1000 |

| Erythritol | 122.1 | Polyvinylpyrrolidone | 10–360 |

| Fructose | 180.2 | Methylcellulose | 30–150 |

| Maltose | 342.3 | Carboxymethylcellulose | 90–700 |

| Mannitol | 182.2 | Agarose | ~120,000 |

| Sorbitol | 182.2 | Xanthan gum | ~2000 |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Mole Ratio | Melting Temperature (°C) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choline chloride | 1-Methyl urea | 1:2 | 29 | [105] |

| Choline chloride | Benzamide | 1:2 | 92 | [105] |

| Choline chloride | 1,1-Dimethyl urea | 1:2 | 149 | [105] |

| Choline chloride | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 1:2 | 97 | [106] |

| Choline chloride | 1,3-Dimethyl urea | 1:2 | 70 | [105] |

| Choline tetrafluoroborate | Urea | 1:2 | 67 | [105] |

| Diethylethanolammonium chloride | Glycerol | 1:2 | −1.2 | [107] |

| Diethylethanolammonium chloride | Trifluoroacetamide | 1:2 | 0.05 | [108] |

| N,N-Diethylenethanolammonium chloride | Glycerol | 1:2 | −1.33 | [109] |

| Tetrabutylammonium chloride | Ethylene glycol | 1:4 | −16.84 | [110] |

| Tetrabutylammonium chloride | Urea | 4:1 | 27.14 | [111] |

| Tetrabutylammonium chloride | Decanoic acid | 1:2 | −11.95 | [112] |

| Tetrapropylammonium bromide | Glycerol | 1:3 | −16.1 | [109] |

| Tetrapropylammonium bromide | Ethylene glycol | 1:3 | −13.3 | [113] |

| Propylammonium bromide | Glycerol | 1:2 | −4 | [114] |

| Category | Methodology | Key Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle technology | β-Galactosidase was coupled with CdSe/ZnS core/shell quantum dots of different sizes and wavelengths. Quantum dots were stabilized by DHLA-CL4 and DHLA-PEG-CL4 ligands. | β-Galactosidase with quantum dots exhibited a 3-fold increase in the kcat value, resulting from an increased product dissociation rate. The unique microenvironment surrounding the hydration layer of the enzyme–QD complex was attributed to the observed effect. | [147] |

| CdSe/ZnS core/shell quantum dots (QDs) of different sizes were conjugated with phosphotriesterase (PTE), followed by extensive characterization. | When conjugated to QDs, a 4-fold increase in the kcat value and a 2-fold increase in the kcat/Km value were shown by PTE. The enhanced activity was attributed to an increase in the enzyme–product dissociation rate, likely due to the varying microenvironment of the hydration layer of the PTE-QD complex. | [148] | |

| A model system was used to test a proposed detailed reaction scheme involving various possible interactions between a substrate and an enzyme–nanoparticle bioconjugate. | The enzyme attached to nanoparticles showed a 3.2-fold increase in the kcat value and a 1.7-fold increase in the kcat/Km value. The proposed detailed reaction scheme suggested that product release becomes rate-limiting when the enzyme is attached to the nanoparticles. | [149] | |

| Mutagenesis | Site saturation and iterative mutagenesis were performed on the identified N-terminal residues 5-YWQN-8 in GH11 xylanase XynLC9 from Bacillus subtilis to produce mutants W6F/Q7H and N8Y. | The W6F/Q7H and N8Y mutants exhibited increased kcat values by 2.6-fold and 1.8-fold, respectively, and kcat/Km values by 1.5-fold and 1.2-fold, respectively. Both mutants were more thermostable and had enlarged active site clefts. | [150] |

| DNA shuffling was employed to mutagenize the trpC gene, which encodes indole glycerol phosphate synthase, from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. | Single and double amino acid mutants had improved activity and increased product release rates. The rate-determining step changed from product dissociation to the chemical step of catalysis. | [17] | |

| Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on specific residues of orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae to give the mutants Q215A and Y217F. | The Q215A and Y217F mutants exhibited increased kcat and decreased kcat/Km, resulting from increased product release rate and a weakening of protein–phosphodianion interactions. | [151] | |

| The structural and functional effects of the evolutionarily changing active site in the biliverdin reductase B (BLVRB) family were investigated by creating multiple human BLVRB mutants through site-directed mutagenesis. | A novel mechanism was proposed where coenzyme “clamps” formed by arginine side chains at positions 14 and 78 slowed coenzyme release and enzyme turnover in wild-type enzymes. However, an inverse association was observed between coenzyme release and enzyme turnover for different BLVRB mutants. | [152] | |

| Enantioselectivity was modified in alcohol dehydrogenase A (ADH-A) from Rhodococcus ruber DSM 44541 by performing saturation mutagenesis on three targeted sites in the catalytic cavity of ADH-A. | The stereoselectivity of the enzyme was altered from (S)- to (R)-1-phenylethanol by the W295A mutant, resulting in a 4-fold increase in the kcat value. W295A showed an enhanced NADH release rate, shifting the rate-determining step from coenzyme release to hydride transfer. Other mutants also showed an increased kcat value relative to the wild type. | [153] | |

| Directed evolution was applied to Escherichia coli S-1,2-propanediol oxidoreductase (FucO) in the study, followed by site-directed mutagenesis of specific residues, including F254 and N151. | A dual role in enzyme function was found to be played by the residue F254, contributing to increased coenzyme dissociation from the active site and a 4-fold increase in the kcat value with S-1,2-propanediol. | [154] | |

| Both natural and non-canonical amino acids were incorporated into bacterial phosphotriesterase (PTE) at position T309 to create different mutants. | Replacing Tyr309 with unnatural amino acids improved the phosphotriesterase turnover rate up to 11-fold and the kcat/Km value up to 4-fold. The rate-limiting product release rate was observed to be increased by the deprotonated 7-hydroxyl group of L-(7-hydroxycoumarin-4-yl)ethylglycine through the electrostatic repulsion of 4-nitrophenolate. | [155] | |

| A novel approach to in vitro evolution of RNA using droplet-based microfluidics was presented, and cycles of random mutagenesis and selection were conducted to evolve the X-motif. | Evolved X-motif ribozyme variants showed an ~28-fold higher kcat value relative to the wild type. This increase in enzyme turnover was attributed to an improved product release rate, which was identified as the rate-limiting step. | [156] | |

| The catalytic activity of Agrobacterium radiobacter phosphotriesterase was enhanced by the genetic incorporation of the unnatural amino acid selenotyrosine (SeHF) at Tyr309. | The SeHF309 mutant resulted in a 12-fold increase in the kcat value and a 3.2-fold increase in the kcat/Km value. The product release pocket was observed to be opened by the SeHF309 mutant, resulting in an increased rate of product release. | [157] | |

| Loop dynamics | Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on E246 in loop L2 located at the entrance of the active site of Pseudomonas aeruginosa d-arginine dehydrogenase to produce the mutants E246Q, E246G, and E246L. | The E246G mutant exhibited a 4-fold increase in the kcat value, while the E246G and E246L variants also showed increased kcat values. The increase in the turnover rate was attributed to an increase in the product release rate resulting from altered loop dynamics. | [158] |

| Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on residues at the interface of the mobile loop of the NS2B-NS3pro complex, a two-component viral protease. | Product release was primarily affected by mutations in the NS2B mobile loop, which triggered a conformational change that activated the catalytic center. A 3.4-fold increase in the kcat value and a 1.5-fold increase in the kcat/Km value were observed in the glycine-linked S83W mutant. | [143] | |

| The thermal stability and catalytic activity of GH11 xylanase XynA from Streptomyces rameus L2001 were improved by rational design when the combined mutations 11YHDGYF16, 23AP24/23SP24, and 32GP33 were introduced to give Mut1 and Mut2 variants. | A 4-fold increase in the kcat value was observed for both Mut1 and Mut2, resulting from a broader catalytic cleft and increased “thumb” flexibility, directly affecting product release. Improved thermal stability was observed in both mutants, with over 85% residual activity after 12 h at 80–90 °C. | [159] | |

| Product inhibition was relieved in chorismate–pyruvate lyase (CPL) by the modulation of its conformational dynamics. Residues at the enzyme’s product-binding site were mutated to increase flap dynamics and facilitate product release. | Mutants exhibited enhanced flap dynamics in chorismate–pyruvate lyase (CPL), characterized by an 8-fold reduction in product inhibition and a 3-fold increase in the kcat value. The product release rate was increased through flap opening without significantly changing the kcat/Km value. | [160] | |

| Modifying transport tunnels | The role of tunnels in DhaA haloalkane dehalogenase was investigated by creating eight mutants via site-directed mutagenesis. | Five pathways were discovered for product release and water exchange, with chloride ions released solely through p1 and alcohol released through all five pathways. All mutants exhibited increased kcat values, ranging from ~3- to 30-fold. | [140] |

| A new transport tunnel was designed in haloalkane dehalogenase via computational design and directed evolution. Mutants were designed to block the native tunnel, allowing for the observation of the properties of the newly opened auxiliary tunnel. | The LinBW mutant, with a blocked native tunnel, showed an increase in both product release rate and a 4-fold increase in the kcat value when the new auxiliary tunnel was opened. The LinBCC mutant, on the other hand, had a 2-fold decrease in enzyme turnover. | [138] | |

| The activity of Rhodococcus rhodochrous haloalkane dehalogenase was enhanced by creating mutants using a novel engineering strategy involving rational design and directed evolution to identify key residues in access tunnels. | Higher enzyme activities were observed by all mutants, with up to a 32-fold increase in the kcat value and a 26-fold increase in the kcat/Km value. There was an increased rate of carbon–halogen breakage and a change in the rate-determining step to product release. | [161] | |

| The conformational dynamics of lysine cyclodeaminase from Streptomyces pristinaespiralis were modulated to address substrate and product inhibitions. The Val61-Val94-SpLCD variant was designed by mutating Ile61 and Ile94 residues associated with substrate and product delivery processes. | The Val61-Val94-SpLCD variant showed improvements in the kcat, kcat/Km, Ki-LYS, and Ki-LPA values by 20, 4, 19, and 9 times, respectively. The expanded substrate and product delivery tunnels of the mutant reduced substrate and product inhibition. | [162] | |

| Using allosteric effectors | VHH domain antibodies as allosteric effectors on the nucleoside hydrolase from Trypanosoma vivax (TvNH) were studied. | VHH 1589 inhibited N-glycosidic bond cleavage while increasing the rates of product release. The data indicated a substrate-dependent effect on kcat and kcat/Km, with a net increase in the kcat value observed for the natural nucleoside 7-methylguanosine, where product release was rate-limiting. | [163] |

| The allosteric effects of heparan sulfate (HS) on cruzipain-mediated kinin release from kininogen (HK) were studied in Trypanosoma cruzi. | HS reduced the inhibitory activity of HK on cruzipain by 10-fold and enhanced the kcat and kcat/Km values by 2.5-fold and 6-fold, respectively. The rate of cruzipain-mediated kinin release was also increased by HS up to 35-fold. | [164] | |

| The structural basis of allosteric product release in Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) was investigated, with a focus on the rate-determining step of tetrahydrofolate (THF) product release. | The transient entry of the NADPH nicotinamide ring into the active site was observed to involve allosteric product release in DHFR, which resulted in the displacement of the THF’s pterin ring. A remodeling of the enzyme structure and conformation of the THF was attributed to the entry of NADPH, which facilitated a rapid product release. | [145] | |

| The mechanism of substrate binding and product release in the geranylgeranylation of Rab proteins by geranylgeranyltransferase type II (GGTase-II) was studied. | GGpp was observed to be an allosteric activator of GGTase-II by causing an increase in enzyme affinity for the Rab7:REP-1 complex. GGpp was also found to facilitate product release by increasing the dissociation rate of prenylated Rab7:REP-1 complex. | [146] |

| Category | Methodology | Key Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational design and directed evolution | Computational design was used to create eight enzymes with two distinct catalytic motifs for the Kemp elimination reaction. Directed in vitro evolution was subsequently applied to refine the computational designs. | The designed enzymes achieved rate enhancements of up to 105 and demonstrated multiple turnovers. Catalytic efficiency was further improved by directed evolution, yielding over 200-fold increase in the kcat/Km value and 106-fold increase in the kcat value relative to the uncatalyzed reaction (kuncat). | [165] |

| Active sites in retro-aldolases were constructed using computational algorithms, which consisted of four distinct catalytic motifs for catalyzing carbon–carbon bond breakage in a nonnatural substrate. The use of explicit water molecules for proton shuffling and charged side-chain networks was included in the design. | Of the 72 experimentally characterized designs, 32 exhibited detectable retro-aldolase activity across various protein folds. Designs that incorporated explicit water molecules were more successful, achieving significant increments in reaction rates. | [166] | |

| Computational design was used to create enzymes capable of catalyzing the bimolecular Diels–Alder reaction. A transaminase enzyme was modified through directed evolution to recognize complex ketone substrates. | High stereoselectivity and substrate specificity were exhibited by the computationally designed Diels–Alder enzymes. The evolved transaminase successfully catalyzed the reaction with a complex ketone substrate, with an 87-fold increase in the kcat value. | [169] | |

| A droplet-based microfluidic screening tool was used to enhance an artificial aldolase by combining computational design and directed evolution to achieve properties comparable to those of the natural enzyme. | The improved enzyme achieved a 109-fold increase in the enzyme turnover rate, with high stereoselectivity and broad substrate tolerance. It was revealed by further analysis that a Lys-Tyr-Asn-Tyr tetrad was important for enzyme activity. | [170] | |

| Incorporating non-canonical amino acids | The active site of an Escherichia coli transketolase variant (S385Y/D469T/R520Q) was incorporated with non-canonical amino acids via site-specific saturation mutagenesis to produce different variants. | The mutants showed a significant increase in the kcat and kcat/Km values. The residue 385 variants exhibited a 43-fold increase in specific activity, a 100% increase in kcat value, a 290% increase in the Km value, and a 240% increase in the kcat/Km value. | [171] |

| Nδ-methylhistidine, a non-canonical amino acid, was incorporated as a catalytic nucleophile into the active site of a novel hydrolytic enzyme, followed by optimization procedures. | Over a 9000-fold increase in the ester hydrolysis rate was observed in the engineered enzyme. Nδ-methylhistidine was revealed as a genetically encodable surrogate for dimethylaminopyridine through crystallographic analysis. Histidine methylation was noted to be important for enzyme activity by blocking the production of nonreactive acyl-enzyme intermediates. | [167] | |

| Mutagenesis | Rational design was used to reconstruct the catalytic pocket and enzyme–substrate interactions of dehydrogenase/reductase EbSDR8 through targeted mutations at specific residues, namely, G94 and S153. | Over a 15-fold improvement in the kcat/Km value was shown by the mutants compared to the wild-type. An increase in the kcat value was also observed for the mutants, and steric repulsion and C−H…π interactions were attributed to this enhanced activity. | [168] |

| Disulfide bonds were eliminated via site-directed mutagenesis in Endoglucanase II (Cel5A) from Trichoderma reesei to create two mutants: C99V and C323H. | A 2-fold increase in both the kcat/Km and kcat values was shown by the C99V mutant, whereas a 1.3-fold increase in the kcat/Km value was shown by the C323H mutant. Both mutants had increased flexibility in the substrate-binding cleft. | [172] | |

| Rational design involving active-site-targeted, site-specific mutagenesis to construct a broad substrate spectrum version of the phenylalanine dehydrogenase (PheDH) from Bacillus halodurans. | Mutant PheDH (E113D-N276L) showed a 6-fold increase in the kcat/Km value for oxidative deamination and a 1.6-fold increase for reductive amination. | [173] | |

| Site-directed mutagenesis of Tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease, with mutations at T17S/N68D/I77V, was used to produce two different mutants: S219N and S219V. | S219N and S219V showed ~100-fold and ~50-fold increases in their kcat values, respectively. S219N was twofold faster than S219V without a change in its Km value. | [174] | |

| Saturation mutagenesis was performed at two positions (165 and 264) near the catalytic Trp171 residue of lignin peroxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium. | A significant increase in the kcat value (2-fold) and the kcat/Km value (13-fold) was shown by the mutants. A 10-fold increase in affinity for azo dye substrates was also observed. | [175] | |

| Site-directed mutagenesis was used to create a lac2-9 mutant from recombinant laccase rlac1338, followed by screening to identify those with improved enzyme activity. | Mutant laccase lac2-9 showed a 3.5-fold increase in specific activity, a ~4-fold increase in the kcat/Km value, and a ~2-fold increase in the kcat value. | [176] | |

| In the study, various mutants were created from arginine deiminase from Pseudomonas plecoglossicida (PpADI) through directed evolution and site-directed mutagenesis, and improved enzyme activity and thermal stability were tested. | The PpADI M9 mutant showed a 64.7-fold increase in the kcat value, a 1.75-fold increase in half-life, and an increase in thermal stability from 47 °C to 54 °C. | [177] | |

| Mutagenesis and strong promoter replacement strategies were used to create mutants of the PAE-degrading enzyme EstJ6, with the aim of enhancing its catalytic activity and expression level. | The EstJ6M1.1, EstJ6M2, and EstJ6M3.1 mutants exhibited an increased kcat value by up to 2.9-fold, 3.1-fold, and 4.3-fold, respectively, and an increased kcat/Km value by up to 3.7-fold, 4.6-fold, and 6-fold, respectively. | [178] | |

| Candida antarctica lipase B (CALB) was modified using proline ionic liquids with varying lengths of hydrophobic alkyl chains on the side. | CALB modified with [ProC12][H2PO4] showed a 3.0-fold increase in hydrolysis activity and a 2.8-fold improvement in the kcat/Km value. Thermal stability was increased as well. | [179] | |

| Random mutagenesis, site-saturation mutagenesis, and combinatorial mutagenesis were used to enhance the activity of a synthesized stereoselective short-chain carbonyl reductase (SCR), an enzyme that produces tert-butyl(3R,5S)-6-chloro-3,5-dihydroxyhexanoate ((3R,5S)-CDHH) for rosuvastatin synthesis. | Mut-Phe145Met/Thr152Ser showed a 1.60-fold increase in the kcat value and a 5.11-fold improvement in the kcat/Km value. A 1.91-fold increase in the kcat value and an 8.07-fold increase in the kcat/Km value were shown by mut-Phe145Tyr/Thr152Ser. A yield of more than 99% in (3R,5S)-CDHH production was also achieved by both mutants. | [180] | |

| Site-directed mutagenesis and N-glycosylation analysis were employed to modify the active site residues of the xylanase XynCDBFV from Neocallimastix patriciarum, resulting in the creation of various mutants. | The W125F/F163W double mutant showed a ~20% increase in the kcat value, and N-glycosylation at Asn-37 was found to play a dominant role in both catalytic activity and thermal stability. | [181] |

| Category | Methodology | Key Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutagenesis | Corner engineering was used to target the transition region in Bacillus subtilis lipase A to create multiple DES-resistant variants with improved activity and thermal stability. | The K88E/N89K mutant showed a 10-fold increase in the kcat/Km value in 30% ChCl–acetamide and a 4.1-fold increase in 95% ChCl–ethylene glycol. A 6.7-fold improvement in thermal resistance was observed for the mutants at 50 °C. The approach was validated with two additional industrial enzymes. | [184] |

| Site-directed mutagenesis was used to modify two main N-glycosylation residues (N45, N64) in cellobiohydrolase I (CBH I) from Trichoderma reesei. | Increased affinity for carboxymethylcellulose, an improved kcat/Km value, and stability up to 80 °C were shown by both mutants. | [185] | |

| The catalytic pocket of dehydrogenase/reductase EbSDR8 was reconstructed via targeted mutations at specific residues: G94 and S153. | The mutants showed over 15-fold increase in the kcat/Km value relative to the wild-type. The increased catalytic efficiency was due to steric repulsion and C−H…π interactions. | [168] | |

| Two rounds of random mutagenesis were performed on a novel esterase (EstKa) from marine Klebsiella aerogenes to obtain the mutants I6E9 and L7B11. | Mutants I6E9 and L7B11 showed 1.56- and 1.65-fold higher kcat/Km values relative to the wild-type EstKa. The Pro96Thr and Gln156Arg mutations increased catalytic efficiency by 1.29- and 1.48-fold, respectively. In contrast, the compound mutant Pro96Thr/Gln156Arg exhibited a 68.9% decrease in the Km value and a 1.41-fold increase in the kcat/Km value. | [186] | |

| The N- and C-terminal domains of keratinase KerSMD were replaced with those from a homologous protease, KerSMF, to generate three different mutants. | N-terminal domain replacement increased the kcat/Km value by >2-fold, whereas C-terminal domain replacement increased the kcat/Km value by 1.5-fold. The kcat/Km value was enhanced by 1.75-fold when both the N- and C-terminal domains were replaced. | [187] | |

| The conformational dynamics of lysine cyclodeaminase from Streptomyces pristinaespiralis were modulated to address substrate and product inhibitions. The Val61-Val94-SpLCD variant was designed by mutating Ile61 and Ile94 residues associated with substrate and product delivery processes. | The Val61-Val94-SpLCD variant showed improvements in the kcat, kcat/Km, Ki-LYS, and Ki-LPA values by 20, 4, 19, and 9 times, respectively. The expanded substrate and product delivery tunnels of the mutant reduced substrate and product inhibition. | [162] | |

| Saturation mutagenesis was performed on position 233 of loop 6 of an acidic, mesophilic GH5 cellulase from Gloeophyllum trabeum to create variants N233A and N233G. | The N233A and N233G mutants showed increased specific activities of 27% and 70%, respectively, and catalytic efficiencies of 45% and 52%, respectively. | [142] | |

| Focused site-directed iterative saturation mutagenesis (FSISM) was applied to rationally design mutations at a non-catalytic cavity in 3-ketosteroid-Δ1-dehydrogenase (Δ1-KstD) from Mycobacterium smegmatis. | All four mutants, H132M, L113F, V419W, and M51L, exhibited a ~30-fold increase in the kcat/Km value and a nearly 10-fold increase in specific activity. | [188] | |

| Site-directed mutagenesis was performed to create four variants based on multiple sequence and 3D structure alignments of endo-β-1,4-xylanase TmxB from Thermotoga maritima. | The T74Y mutant showed a 1.3-fold increase in specific activity and a 1.6-fold increase in the kcat/Km value. The DY mutants (two amino acid insertions) showed a 1.2-fold increase in the kcat/Km value. | [189] | |

| Rational design was used to engineer a substrate-binding cavity and entrance tunnel in L-amino acid deaminase from Proteus mirabilis. | The Q92A mutant exhibited an increased binding cavity volume (994.2 Å3), enzyme activity (191.36 U mg1), and kcat/Km value (1.23 mM1min1). The T436/W438A mutant also showed an increased binding cavity volume and kcat/Km value. | [190] | |

| Nanoparticle technology | CdSe/ZnS core/shell quantum dots (QDs) of different sizes were conjugated onto phosphotriesterase (PTE), followed by extensive characterization. | There was a 2-fold increase in the kcat/Km value when the enzyme was conjugated with QDs. The results indicated that the increase in catalytic efficiency was due to the different microenvironment of the hydration layer of the PTE-QD bioconjugate. | [148] |

| A proposed model system consisting of a detailed reaction scheme was used to test different possible interactions between a substrate and an enzyme conjugated with nanoparticles. | There was a 1.7-fold increase in the kcat/Km value when the enzyme was conjugated to nanoparticles. The data revealed that the product release step becomes rate-limiting when the enzyme is attached to the nanoparticles. | [149] | |

| Loop dynamics | The residues at the interface of the mobile loop of the NS2B-NS3pro complex, a two-component viral protease, were mutated via site-directed mutagenesis. | The NS2B mobile loop mutants altered the rate of product release by causing a conformational change that activated the catalytic center. The glycine-linked S83W mutant had a 1.5-fold increase in the kcat/Km value relative to the wild-type. | [143] |

| Incorporating non-canonical amino acids | Non-canonical amino acids were incorporated into the active site of an Escherichia coli transketolase variant (S385Y/D469T/R520Q) through site-specific saturation mutagenesis to produce different variants. | A 43-fold increase in specific activity, a 290% increase in the Km value, and a 240% increase in the kcat/Km value were exhibited by the residue 385 variants. | [171] |

| Tyr309 was replaced with two non-canonical amino acids, L-(7-hydroxycoumarin-4-yl)ethylglycine (Hco) and L-(7-methylcoumarin-4-yl)ethylglycine, in bacterial phosphotriesterase. | The mutants with unnatural amino acids had increased phosphotriesterase turnover rates, up to 11-fold, and a kcat/Km value up to 4-fold. The deprotonated 7-hydroxyl group of Hco was observed to increase the rate-limiting product release rate via electrostatic repulsion of 4-nitrophenolate. | [155] | |

| The non-canonical amino acid, Nδ-methylhistidine, was used as a catalytic nucleophile to design a novel hydrolytic enzyme. | The novel enzyme exhibited an over 9000-fold increase in the ester hydrolysis rate and a 15-fold increase in the kcat/Km value. Crystallographic analysis proved Nδ-methylhistidine as a genetically encodable surrogate for dimethylaminopyridine. | [167] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atampugbire, G.A.; Quaye, J.A.; Gadda, G. How Mechanistic Enzymology Helps Industrial Biocatalysis: The Case for Kinetic Solvent Viscosity Effects. Catalysts 2025, 15, 736. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15080736

Atampugbire GA, Quaye JA, Gadda G. How Mechanistic Enzymology Helps Industrial Biocatalysis: The Case for Kinetic Solvent Viscosity Effects. Catalysts. 2025; 15(8):736. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15080736

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtampugbire, Gabriel Atampugre, Joanna Afokai Quaye, and Giovanni Gadda. 2025. "How Mechanistic Enzymology Helps Industrial Biocatalysis: The Case for Kinetic Solvent Viscosity Effects" Catalysts 15, no. 8: 736. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15080736

APA StyleAtampugbire, G. A., Quaye, J. A., & Gadda, G. (2025). How Mechanistic Enzymology Helps Industrial Biocatalysis: The Case for Kinetic Solvent Viscosity Effects. Catalysts, 15(8), 736. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15080736