Aspergillus spp. As an Expression System for Industrial Biocatalysis and Kinetic Resolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Bibliographic Search: Comparisons and Considerations About Traditional and Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Bibliography Database Search Platforms

3. Aspergillus spp. Biocatalysts Applied at Kinetic Resolution of Enantiomers

3.1. Lipase

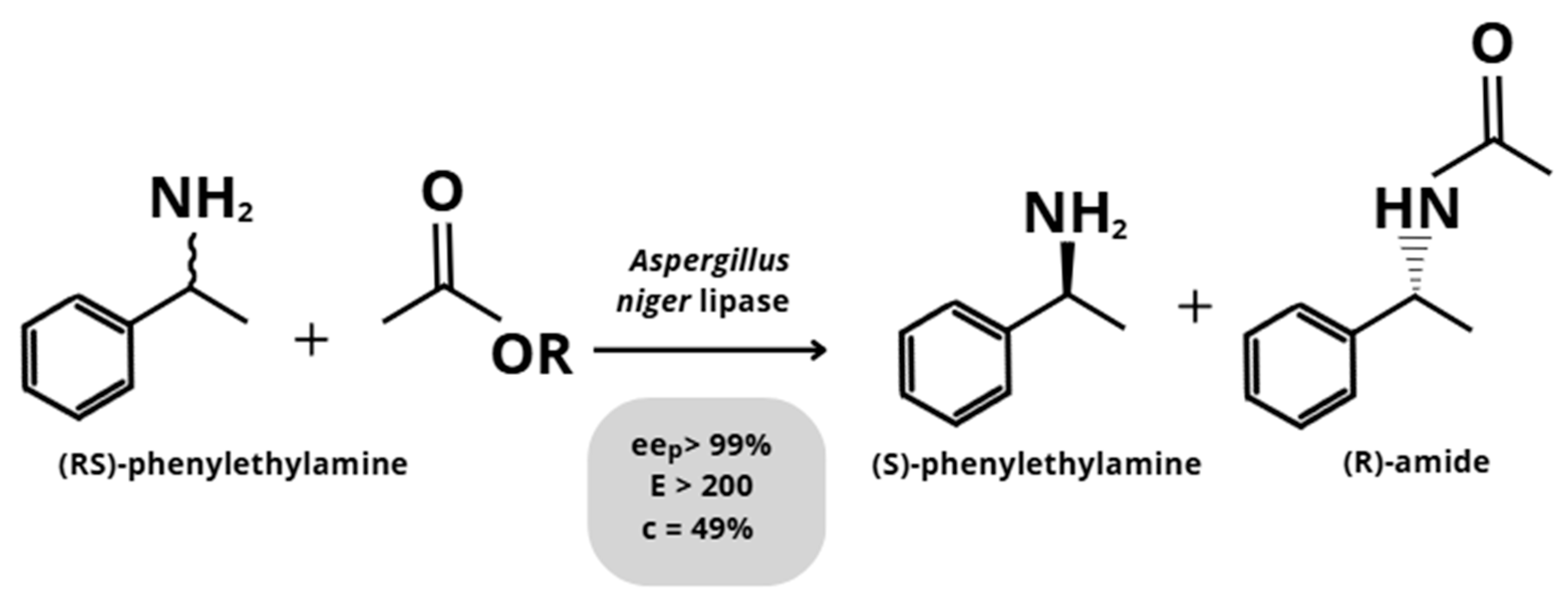

3.1.1. Aspergillus niger

3.1.2. Aspergillus oryzae

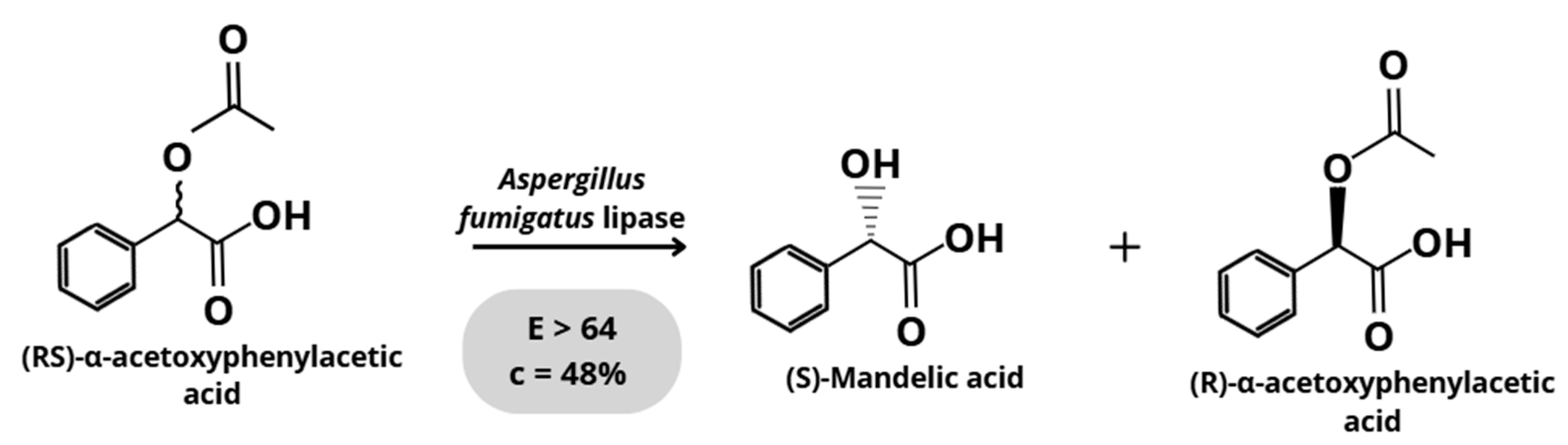

3.1.3. Aspergillus fumigatus

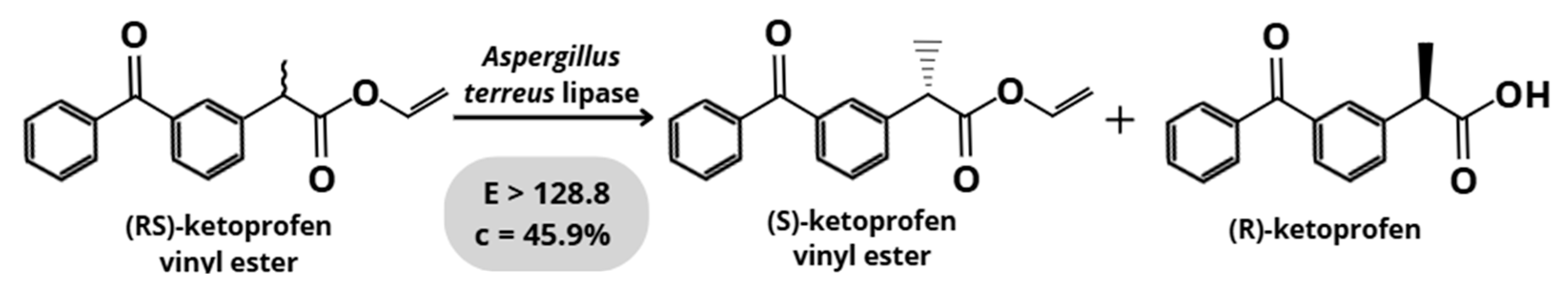

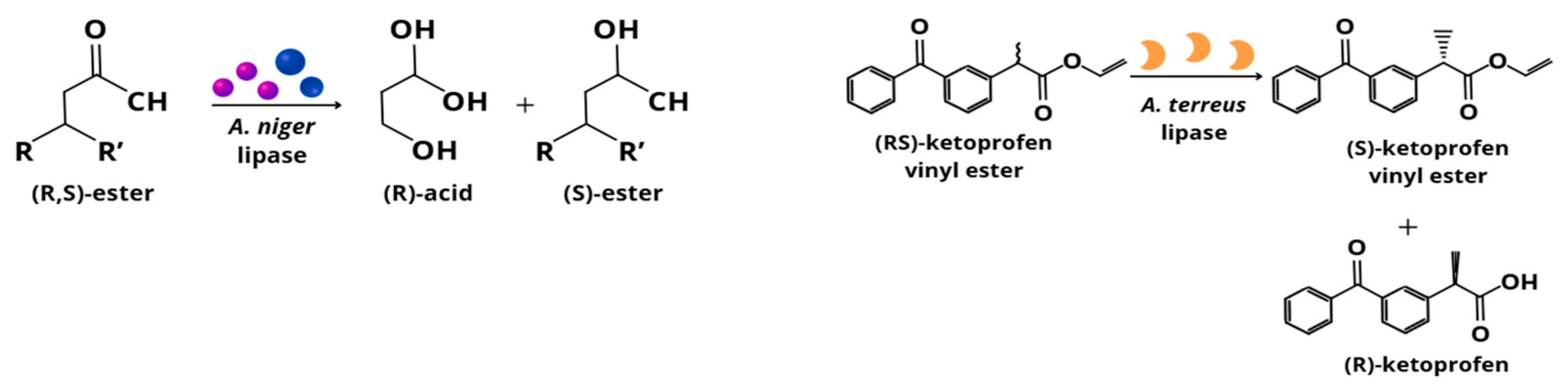

3.1.4. Aspergillus terreus

3.1.5. Aspergillus melleus

3.1.6. Aspergillus tamarii

3.2. Other Enzymes

4. Strategies to Enhance Lipases for Improved Kinetic Resolution of Enantiomers

4.1. Optimization Approaches for Recombinant Lipase Production in Filamentous Fungi

4.2. Aspergillus as a Eukaryotic Production System for Functional Lipases

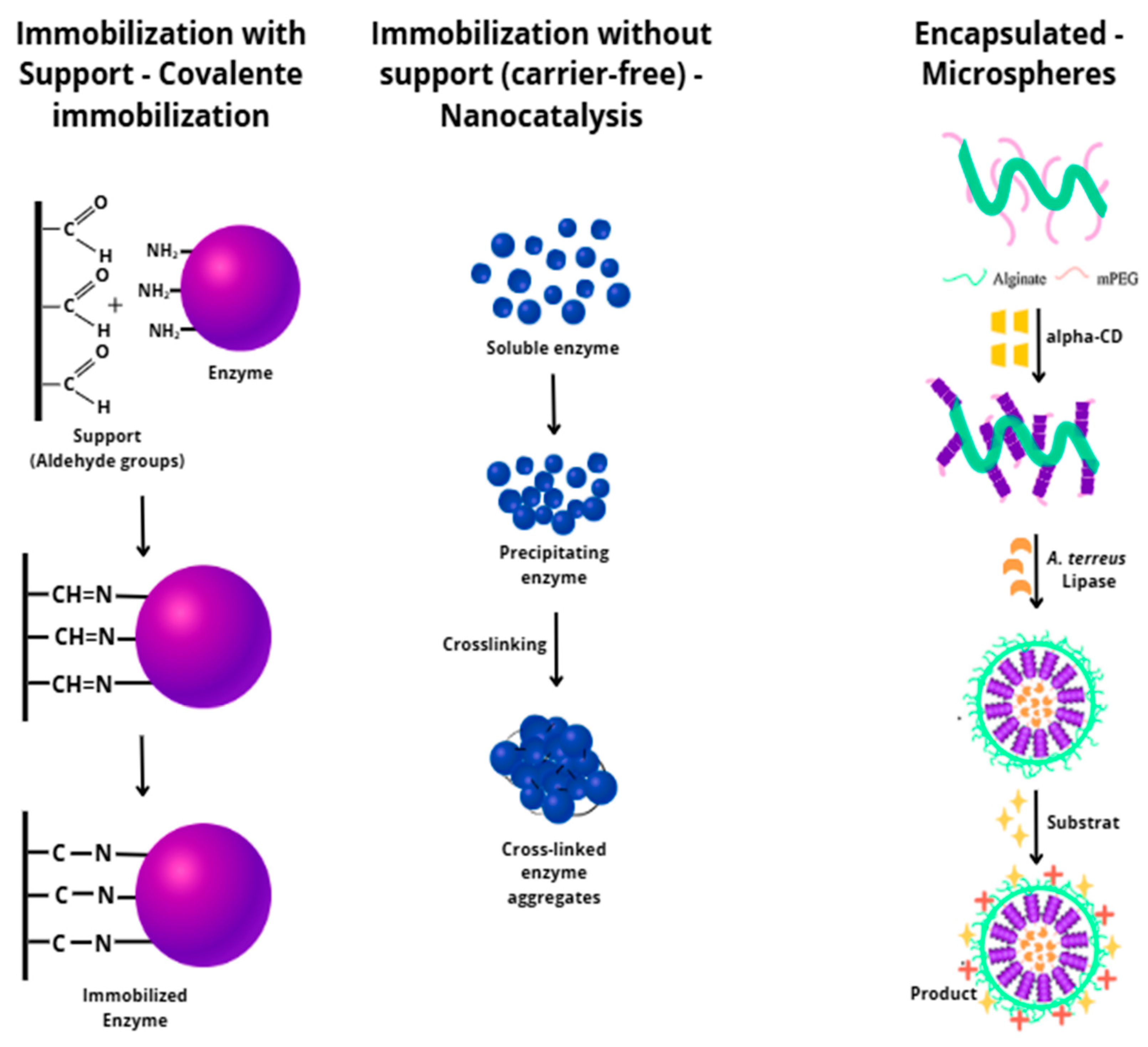

4.3. Lipase Immobilization: Techniques, Advantages, and Applications in Kinetic Resolution

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KR | Kinetic resolution |

| c | Conversion |

| ees | Enantiomeric excess of the substrate |

| eep | Enantiomeric excess of the product |

| E ratio | Enantiomeric ratio |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| LLMs | Large language models |

| GRAS | Generally recognized as safe |

| R-PPAM | (R)-sulfonylethanol |

| Vmax | High maximum velocity |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

| ERAD | Endoplasmic reticulum–associated degradation |

| UPS | Regulation of unconventional protein secretion |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| SILP | Supported ionic liquid phase |

| L-ABA | L-2-aminobutyric acid |

| USD | US dollar |

| Km | Michaelis-Menten constant |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| Cas9 | Programmable endonuclease that allows targeted cleavage of DNA |

| NHEJ | Non-homologous end joining |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

References

- Nji, Q.N.; Babalola, O.O.; Mwanza, M. Soil Aspergillus Species, Pathogenicity and Control Perspectives. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merad, Y.; Derrar, H.; Belmokhtar, Z.; Belkacemi, M. Aspergillus Genus and Its Various Human Superficial and Cutaneous Features. Pathogens 2021, 10, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, F.-J.; Hu, S.; Wang, B.-T.; Jin, L. Advances in Genetic Engineering Technology and Its Application in the Industrial Fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 644404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Summa, D.; Zappaterra, F.; Blo, R.; Tamburini, E. Aspergillus oryzae Grown on Rice Hulls Used as an Additive for Pretreatment of Starch-Containing Wastewater from the Pulp and Paper Industry. Fermentation 2021, 7, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, R.A.; Visagie, C.M.; Houbraken, J.; Hong, S.-B.; Hubka, V.; Klaassen, C.H.W.; Perrone, G.; Seifert, K.A.; Susca, A.; Tanney, J.B.; et al. Phylogeny, Identification and Nomenclature of the Genus Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 78, 141–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Hao, L.; Gan, Y.; Xin, T.; Lou, Q.; Xu, W.; Song, J. Identification of Closely Related Species in Aspergillus through Analysis of Whole-Genome. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1323572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, K.; Valero, C.; Conn, D.P.; Vere, G.; Cook, P.C.; Bromley, M.J.; Bowyer, P.; Gago, S. Pathogenicity and Virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus. Virulence 2023, 14, 2172264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorán, S.; Carramiñana, J.J.; Juan, T.; Ariño, A.; Herrera, M. Inhibition of Aspergillus parasiticus Growth and Aflatoxins Production by Natural Essential Oils and Phenolic Acids. Toxins 2022, 14, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, A.M.; El-Wakil, D.A.; Attia, M.S.; Ali, O.M.; AbdElgawad, H.; Hashem, A.H. Inhibition of Aspergillus flavus Growth and Aflatoxin Production in Zea Mays L. Using Endophytic Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contesini, F.J.; Lopes, D.B.; Macedo, G.A.; Nascimento, M.D.G.; Carvalho, P.D.O. Aspergillus spp. Lipase: Potential Biocatalyst for Industrial Use. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2010, 67, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Hu, D.; Zong, X.; Li, J.; Ding, L.; Wu, M.; Li, J. Enantioconvergent Hydrolysis of Racemic Styrene Oxide at High Concentration by a Pair of Novel Epoxide Hydrolases into (R)-Phenyl-1,2-Ethanediol. Biotechnol. Lett. 2017, 39, 1917–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; He, Y.-H.; Guan, Z. Bio-Catalytic Bis-Michael Reaction for Generating Cyclohexanones with a Quaternary Carbon Center Using Glucoamylase. Catal. Lett. 2017, 147, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.-C.; Zheng, Y.-G.; Shen, Y.-C. A Simple Method to Determine Concentration of Enantiomers in Enzyme-Catalyzed Kinetic Resolution. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R.A.; Woodley, J.M. Role of Biocatalysis in Sustainable Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 801–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornscheuer, U.T. Microbial Carboxyl Esterases: Classification, Properties and Application in Biocatalysis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 26, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reetz, M.T. Biocatalysis in Organic Chemistry and Biotechnology: Past, Present, and Future. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12480–12496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giglio, A.D.; Costa, M.U.P.D. The Use of Artificial Intelligence to Improve the Scientific Writing of Non-Native English Speakers. Rev. Assoc. Médica Bras. 2023, 69, e20230560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Kim, T.; Byun, H.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.; Sim, H. SCISPACE: A Scientific Collaboration Workspace for File Systems in Geo-Distributed HPC Data Centers. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.08228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, W. A Tale of Two Databases: The Use of Web of Science and Scopus in Academic Papers. Scientometrics 2020, 123, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodley, J.M. Ensuring the Sustainability of Biocatalysis. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremasco, M.A. A fronteira da indústria farmacêutica no Brasil: Enantiômeros. Ciênc. E Cult. 2013, 65, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewalt, V.; Shanahan, D.; Gregg, L.; La Marta, J.; Carrillo, R. The Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) Process for Industrial Microbial Enzymes. Ind. Biotechnol. 2016, 12, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, J.-J.; Fan, L.; Ju, X.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, F.-J.; Zhao, J.; Xu, J.-H. Expression and Characterization of a Novel Enantioselective Lipase from Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 168, 1820–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Gu, X.; Liu, Y.; Ge, J.; Zhu, Q. Bioproduction of L-2-Aminobutyric Acid by a Newly-Isolated Strain of Aspergillus tamarii ZJUT ZQ013. Catal. Lett. 2017, 147, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamborini, L.; Romano, D.; Pinto, A.; Contente, M.; Iannuzzi, M.C.; Conti, P.; Molinari, F. Biotransformation with Whole Microbial Systems in a Continuous Flow Reactor: Resolution of (RS)-Flurbiprofen Using Aspergillus oryzae by Direct Esterification with Ethanol in Organic Solvent. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 6090–6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Meng, Y.; Yu, X. Immobilization of Aspergillus terreus Lipase in Self-Assembled Hollow Nanospheres for Enantioselective Hydrolysis of Ketoprofen Vinyl Ester. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 194, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Wang, Z.; Qian, J. Efficient Kinetic Resolution of (RS)-1-phenylethanol by a Mycelium-bound Lipase from a Wild-type Aspergillus oryzae Strain. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2017, 64, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.D.; Guo, B.H.; Wang, Z.; Qian, J.Q. Surfactant-Modified Aspergillus oryzae Lipase as a Highly Active and Enantioselective Catalyst for the Kinetic Resolution of (RS)-1-Phenylethanol. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, K. Microbial Lipases Form Versatile Tools for Biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 1998, 16, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauwerdink, A.; Kazlauskas, R.J. How the Same Core Catalytic Machinery Catalyzes 17 Different Reactions: The Serine-Histidine-Aspartate Catalytic Triad of α/β-Hydrolase Fold Enzymes. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6153–6176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, A.A.; Abo-Kamar, A.M.; Elkotb, E.S.; Al-Madboly, L.A. Microbial Lipases: Advances in Production, Purification, Biochemical Characterization, and Multifaceted Applications in Industry and Medicine. Microb. Cell Factories 2025, 24, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Shimada, H.; Yamada, R.; Shiratori-Takano, H.; Sayo, N.; Saito, T.; Takano, H.; Beppu, T.; Ueda, K. Preparation of Optically-Active 3-Pyrrolidinol and Its Derivatives from 1-Benzoylpyrrolidinol by Hydroxylation with Aspergillus spp. and Stereo-Selective Esterification by a Commercial Lipase. Biotechnol. Lett. 2014, 36, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Verma, V.; Dubey, V.K.; Srivastava, A.; Garg, S.K.; Singh, V.P.; Arora, P.K. Industrial Applications of Fungal Lipases: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1142536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilissão, C.; Carvalho, P.D.O.; Nascimento, M.D.G. Potential Application of Native Lipases in the Resolution of (RS)-Phenylethylamine. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2010, 21, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, M.; Jana, N.; Nanda, S. Stereoselective Desymmetrization of 2,2-Bishydroxymethyl-1-Tetralones by Iodocyclization, Synthesis of Novel Enantiopure [6.6.5] Tricyclic Framework and Chemoenzymatic Diversity Generation. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 2152–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilissão, C.; Carvalho, P.D.O.; Nascimento, M.D.G. The Influence of Conventional Heating and Microwave Irradiation on the Resolution of (RS)-Sec-Butylamine Catalyzed by Free or Immobilized Lipases. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2012, 23, 1688–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Bhaumik, J.; Banoth, L.; Banesh, S.; Banerjee, U.C. Chemoenzymatic Route for the Synthesis of (S)-Moprolol, a Potential β-Blocker. Chirality 2016, 28, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettireddy, S.; Chandupatla, V.; Veeresham, C. Enantioselective Resolution of (R,S)-Carvedilol to (S)-(−)-Carvedilol by Biocatalysts. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2017, 7, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, K.B.; Cruz, D.M.V.; Oliveira, A.R.T.; da Silva, M.R.; de Lemos, T.L.G.; Oliveira, M.C.F.; Bernardo, R.D.S.; de Sousa, J.R.; Zanatta, G.; Nasário, F.D.; et al. Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Apremilast: A Study Using Ketoreductases and Lipases. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2021, 32, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degórska, O.D. Immobilized Lipase in Resolution of Ketoprofen Enantiomers: Examination of Biocatalysts Properties and Process Characterization. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andzans, Z.; Adlere, I.; Versilovskis, A.; Krasnova, L.; Grinberga, S.; Duburs, G.; Krauze, A. Effective Method of Lipase-Catalyzed Enantioresolution of 6-Alkylsulfanyl-1,4-Dihydropyridines. Heterocycles 2014, 89, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Wang, Z. Resolution of (R, S)-Ethyl-2-(4-Hydroxyphenoxy) Propanoate Using Lyophilized Mycelium of Aspergillus oryzae WZ007. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2013, 97, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, J. A Novel Lipase from Aspergillus oryzae Catalyzed Resolution of (R, S)-ethyl 2-bromoisovalerate. Chirality 2020, 32, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, J. Enantioselective Resolution of (R, S)-2-Phenoxy-Propionic Acid Methyl Ester by Covalent Immobilized Lipase from Aspergillus oryzae. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 190, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T.sriwong, K.; Matsuda, T. Recent Advances in Enzyme Immobilization Utilizing Nanotechnology for Biocatalysis. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2022, 26, 1857–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, J. A Novel Lipase from Aspergillus oryzae WZ007 Catalyzed Synthesis of Brivaracetam Intermediate and Its Enzymatic Characterization. Chirality 2021, 33, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reetz, M.T.; Zheng, H. Manipulating the Expression Rate and Enantioselectivity of an Epoxide Hydrolase by Using Directed Evolution. Chembiochem 2011, 12, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; OuYang, X.; Hu, Z. Enhancement of Epoxide Hydrolase Production by60 Co Gamma and UV Irradiation Mutagenesis of Aspergillus niger ZJB-09103. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2017, 64, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.-Y.; Liao, X.; Jing, W.-W.; Liu, K.-K.; Ren, Q.-G.; He, Y.-C.; Hu, D. Rational Mutagenesis of an Epoxide Hydrolase and Its Structural Mechanism for the Enantioselectivity Improvement toward Chiral Ortho-Fluorostyrene Oxide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Tang, C.-D.; Yang, B.; Liu, J.-C.; Yu, T.; Deng, C.; Wu, M.-C. Expression of a Novel Epoxide Hydrolase of Aspergillus usamii E001 in Escherichia coli and Its Performance in Resolution of Racemic Styrene Oxide. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 42, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, D.; Tükel, S.S.; Alagöz, D.; Alptekin, Ö. Preparative-Scale Kinetic Resolution of Racemic Styrene Oxide by Immobilized Epoxide Hydrolase. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2011, 49, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascotti, M.L.; Juri Ayub, M.; Dudek, H.; Sanz, M.K.; Fraaije, M.W. Cloning, Overexpression and Biocatalytic Exploration of a Novel Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenase from Aspergillus fumigatus Af293. AMB Express 2013, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, B.K.; Kuwar, S.S.; Golegaonkar, S.B.; Nene, S.N. Preparation of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates of l-Aminoacylase via Co-Aggregation with Polyethyleneimine. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2012, 74, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesko, K.; Steiner, K.; Breinbauer, R.; Schwab, H.; Schürmann, M.; Strohmeier, G.A. Investigation of One-Enzyme Systems in the ω-Transaminase-Catalyzed Synthesis of Chiral Amines. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2013, 96, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contesini, F.J.; Davanço, M.G.; Borin, G.P.; Vanegas, K.G.; Cirino, J.P.G.; Melo, R.R.D.; Mortensen, U.H.; Hildén, K.; Campos, D.R.; Carvalho, P.D.O. Advances in Recombinant Lipases: Production, Engineering, Immobilization and Application in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wu, Y.; Long, S.; Feng, S.; Jia, X.; Hu, Y.; Ma, M.; Liu, J.; Zeng, B. Aspergillus oryzae as a Cell Factory: Research and Applications in Industrial Production. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boppidi, K.R.; Ribeiro, L.F.C.; Iambamrung, S.; Nelson, S.M.; Wang, Y.; Momany, M.; Richardson, E.A.; Lincoln, S.; Srivastava, R.; Harris, S.D.; et al. Altered Secretion Patterns and Cell Wall Organization Caused by Loss of PodB Function in the Filamentous Fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umemura, M.; Kuriiwa, K.; Dao, L.V.; Okuda, T.; Terai, G. Promoter Tools for Further Development of Aspergillus oryzae as a Platform for Fungal Secondary Metabolite Production. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2020, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübeck, M.; Lübeck, P.S. Fungal Cell Factories for Efficient and Sustainable Production of Proteins and Peptides. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Gao, L.; Song, X.; Li, X.; Qu, Y.; Liu, G. Genetic Engineering and Raising Temperature Enhance Recombinant Protein Production with the Cdna1 Promoter in Trichoderma reesei. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2022, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathis, H.; Naquin, D.; Margeot, A.; Bidard, F. Enhanced Heterologous Gene Expression in Trichoderma reesei by Promoting Multicopy Integration. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufel, F.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Johansen, A.R.; Gíslason, M.H.; Pihl, S.I.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; Von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 6.0 Predicts All Five Types of Signal Peptides Using Protein Language Models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1023–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandomenico, A.; Sivaccumar, J.P.; Ruvo, M. Evolution of Escherichia coli Expression System in Producing Antibody Recombinant Fragments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropero-Pérez, C.; Marcos, J.F.; Manzanares, P.; Garrigues, S. Increasing the Efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing in the Citrus Postharvest Pathogen Penicillium Digitatum. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2024, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Jiang, X.; Xu, F.; Tian, X.; Chu, J. Constructing pyrG Marker by CRISPR/Cas Facilities the Highly-Efficient Precise Genome Editing on Industrial Aspergillus niger Strain. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 48, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamalampudi, S.; Talukder, M.M.R.; Hama, S.; Tanino, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Kondo, A.; Fukuda, H. Development of Recombinant Aspergillus oryzae Whole-Cell Biocatalyst Expressing Lipase-Encoding Gene from Candida antarctica. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 75, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarczynska, Z.D.; Rendsvig, J.K.H.; Pagels, N.; Viana, V.R.; Nødvig, C.S.; Kirchner, F.H.; Strucko, T.; Nielsen, M.L.; Mortensen, U.H. DIVERSIFY: A Fungal Multispecies Gene Expression Platform. ACS Synth. Biol. 2021, 10, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntana, F.; Mortensen, U.H.; Sarazin, C.; Figge, R. Aspergillus: A Powerful Protein Production Platform. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, J.E.; Marles-Wright, J.; Giachino, A. A User’s Guide to Golden Gate Cloning Methods and Standards. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 3551–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanegas, K.G.; Rendsvig, J.K.H.; Jarczynska, Z.D.; Cortes, M.V.D.C.B.; Van Esch, A.P.; Morera-Gómez, M.; Contesini, F.J.; Mortensen, U.H. A Mad7 System for Genetic Engineering of Filamentous Fungi. J. Fungi 2022, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Luo, X.; Chen, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, H. Gibson Assembly Interposition Improves Amplification Efficiency of Long DNA and Multifragment Overlap Extension PCR. BioTechniques 2023, 74, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antsotegi-Uskola, M.; D’Ambrosio, V.; Jarczynska, Z.D.; Vanegas, K.G.; Morera-Gómez, M.; Wang, X.; Larsen, T.O.; Mouillon, J.-M.; Mortensen, U.H. RoCi—A Single Step Multi-Copy Integration System Based on Rolling-Circle Replication. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Srivastava, R. Deep Learning in Structural Bioinformatics: Current Applications and Future Perspectives. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Kan, S.B.J.; Lewis, R.D.; Wittmann, B.J.; Arnold, F.H. Machine Learning-Assisted Directed Protein Evolution with Combinatorial Libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 8852–8858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Huang, M. Navigating the Landscape of Enzyme Design: From Molecular Simulations to Machine Learning. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 8202–8239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, F.-Z.; Arnold, F.H. Opportunities and Challenges for Machine Learning-Assisted Enzyme Engineering. ACS Cent. Sci. 2024, 10, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illanes, A.; Cauerhff, A.; Wilson, L.; Castro, G.R. Recent Trends in Biocatalysis Engineering. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 115, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.C.; Ortiz, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Torres, R.; Fernández-Lafuente, R. Modifying Enzyme Activity and Selectivity by Immobilization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6290–6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szelwicka, A.; Boncel, S.; Jurczyk, S.; Chrobok, A. Exceptionally Active and Reusable Nanobiocatalyst Comprising Lipase Non-Covalently Immobilized on Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes for the Synthesis of Diester Plasticizers. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2019, 574, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.; Moody, T.S.; Smyth, M.; Wharry, S. A Perspective on Continuous Flow Chemistry in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020, 24, 1802–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesionowski, T.; Zdarta, J.; Krajewska, B. Enzyme Immobilization by Adsorption: A Review. Adsorption 2014, 20, 801–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghraby, Y.R.; El-Shabasy, R.M.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Azzazy, H.M.E.-S. Enzyme Immobilization Technologies and Industrial Applications. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 5184–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifabad, M.E.; Hodgson, B.; Jellite, M.; Mercer, T.; Sen, T. Enzyme Immobilised Novel Core–Shell Superparamagnetic Nanocomposites for Enantioselective Formation of 4-(R)-Hydroxycyclopent-2-En-1-(S)-Acetate. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11185–11187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolny, A.; Siewniak, A.; Zdarta, J.; Ciesielczyk, F.; Latos, P.; Jurczyk, S.; Nghiem, L.D.; Jesionowski, T.; Chrobok, A. Supported Ionic Liquid Phase Facilitated Catalysis with Lipase from Aspergillus oryzae for Enhance Enantiomeric Resolution of Racemic Ibuprofen. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, D.; Tükel, S.S.; Alptekin, Ö.; Alagöz, D. Immobilized Aspergillus niger Epoxide Hydrolases: Cost-Effective Biocatalysts for the Preparation of Enantiopure Styrene Oxide, Propylene Oxide and Epichlorohydrin. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2013, 88, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna, Y.; Sandoval, J.; Saade, H.; López, R.G.; Martinez, J.L.; Colunga, E.M.; de la Cruz, G.; Segura, E.P.; Arévalo, F.J.; Zon, M.A.; et al. Immobilization of Aspergillus niger Lipase on Chitosan-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles Using Two Covalent-Binding Methods. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 38, 1437–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karboune, S.; Archelas, A.; Baratti, J.C. Free and Immobilized Aspergillus niger Epoxide Hydrolase-Catalyzed Hydrolytic Kinetic Resolution of Racemic p-Chlorostyrene Oxide in a Neat Organic Solvent Medium. Process Biochem. 2010, 45, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijitha, C.; Swetha, E.; Veeresham, C. Enantioselective Conversion of Racemic Felodipine to S(−)-Felodipine by Aspergillus niger; and Lipase AP6 Enzyme. Adv. Microbiol. 2016, 06, 1062–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, V.; Wanka, F.; Van Gent, J.; Arentshorst, M.; Van Den Hondel, C.A.M.J.J.; Ram, A.F.J. Fungal Gene Expression on Demand: An Inducible, Tunable, and Metabolism-Independent Expression System for Aspergillus niger. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 2975–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.-Y.; Yang, Z.-M.; Pan, L.; Zheng, S.-P.; Han, S.-Y.; Lin, Y. Displaying Candida antarctica Lipase B on the Cell Surface of Aspergillus niger as a Potential Food-Grade Whole-Cell Catalyst. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 41, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solarte, C.; Yara-Varón, E.; Eras, J.; Torres, M.; Balcells, M.; Canela-Garayoa, R. Lipase Activity and Enantioselectivity of Whole Cells from a Wild-Type Aspergillus flavus Strain. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2014, 100, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Hu, B.-C.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Zang, J.; Wu, M.-C. Nearly Perfect Kinetic Resolution of Racemic O-Nitrostyrene Oxide by AuEH2, a Microsomal Epoxide Hydrolase from Aspergillus usamii, with High Enantio- and Regio-Selectivity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 169, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Platform | Search Method | Database | Main Resources | User Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elicit | LLM-based semantic search | Semantic Scholar | Basic doc info, Q&A, structured results | Easy to use, but limited to ≤2022 | [17] |

| SciSpace | AI + keyword search | Multiple sources | Versatile search, summaries | Broader coverage, but less precise | [18] |

| Web of Science | Boolean operators | Proprietary (WoS) | Advanced filters, citation metrics | Boolean NOT failed in some queries | [19] |

| Aspergillus Species | Substrate of Interest for Separation | Catalyzed Reaction | Enantiomeric Ratio (E) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus niger | (RS)-phenylethylamine | Transesterification | >200 | [34] |

| Prochiral 2,2-bishydroxymethyl-1-tetralone | Hydrolysis | 160 | [35] | |

| (RS)-sec-Butylamine | Hydrolysis | >200 | [36] | |

| Moprolol (1-(isopropylamino)-3-(O-methoxy phenoxy)-2propanol) | Transesterification | 307 | [37] | |

| Racemic Carvedilol | Transesterification | 11.34 | [38] | |

| (RS)-phenylethylamine | Transesterification | >200 | [39] | |

| Racemic ketoprofen methyl ester | Hydrolysis | 99.7 | [40] | |

| Aspergillus melleus | 6-alkylsulfanyl-1,4-dihydropyridines | Hydrolysis | 11.58 | [41] |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | (RS)-α-acetoxyphenylacetic acid (APA) | Hydrolysis | 64 | [23] |

| Aspergillus terreus | Racemic ketoprofen vinyl ester | Hydrolysis | 128.8 | [26] |

| Aspergillus tamarii | Racemic ketoprofen vinyl ester | Hydrolysis | 257 | [24] |

| Aspergillus oryzae | (RS)-ethyl-2-(4-hydroxyphenoxy) | Hydrolysis | >200 | [42] |

| (RS)-1- phenylethanol | Transesterification | >200 | [27] | |

| (RS)-1- phenylethanol | Transesterification | >200 | [28] | |

| (RS)-ethyl 2-bromoisovalerate | Hydrolysis | 120 | [43] | |

| (RS)-2-phenoxypropionic acid (PPAM) | Hydrolysis | - | [44] | |

| (RS)-phenylethylamine | Transesterification | >200 | [45] |

| Aspect | Protein Origin | Secretion Efficiency | Optimization Strategies | Impact on KR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homologous Expression | Native to host fungus | High, due to compatibility with the host’s secretory pathway | Strong promoters, codon optimization, modulation of UPR/ERAD pathways | High enantioselectivity and efficient production |

| Heterologous Expression | From a different organism | Often lower; may require engineering (fusion proteins, heterologous signal peptides, purification tags) [15] | Fusion with carrier proteins [15], heterologous signal peptides [65], codon optimization, purification/affinity tags, immobilization | Can maintain or improve catalytic efficiency and enantioselectivity, depending on construct design and folding quality |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garcia, P.H.D.; Regagnin Montico, J.; Pontes Barichello, A.; Pilissão, C.; Contesini, F.J.; Mortensen, U.H.; Carvalho, P.d.O. Aspergillus spp. As an Expression System for Industrial Biocatalysis and Kinetic Resolution. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121174

Garcia PHD, Regagnin Montico J, Pontes Barichello A, Pilissão C, Contesini FJ, Mortensen UH, Carvalho PdO. Aspergillus spp. As an Expression System for Industrial Biocatalysis and Kinetic Resolution. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121174

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcia, Pedro Henrique Dias, Júlia Regagnin Montico, Alexssander Pontes Barichello, Cristiane Pilissão, Fabiano Jares Contesini, Uffe Hasbro Mortensen, and Patrícia de Oliveira Carvalho. 2025. "Aspergillus spp. As an Expression System for Industrial Biocatalysis and Kinetic Resolution" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121174

APA StyleGarcia, P. H. D., Regagnin Montico, J., Pontes Barichello, A., Pilissão, C., Contesini, F. J., Mortensen, U. H., & Carvalho, P. d. O. (2025). Aspergillus spp. As an Expression System for Industrial Biocatalysis and Kinetic Resolution. Catalysts, 15(12), 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121174