Influence of Ag/CeO2-Supported Catalysts Derived from Ce-MOFs on Low-Temperature Oxidation of Unregulated Methanol Emissions from Methanol Engines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

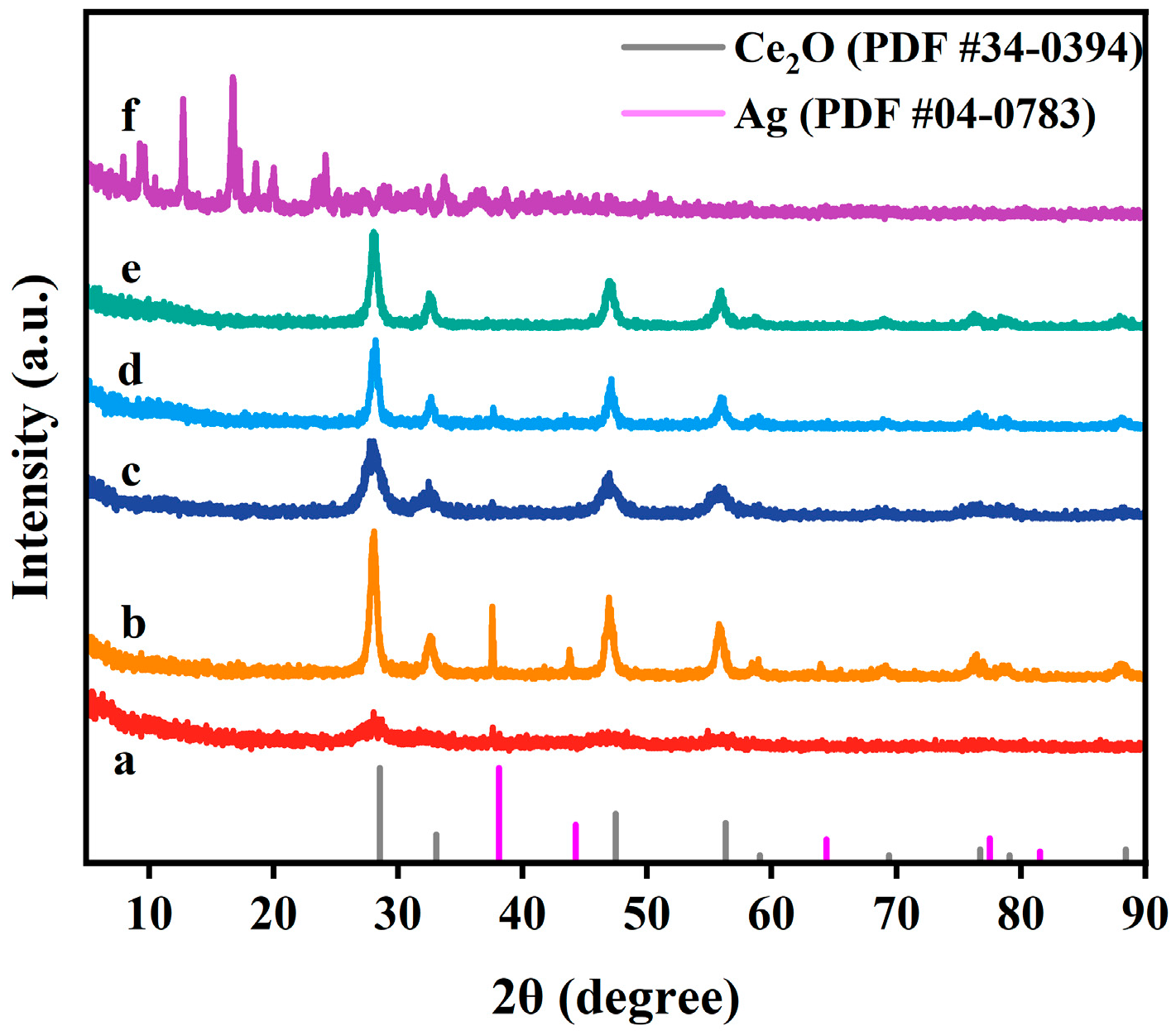

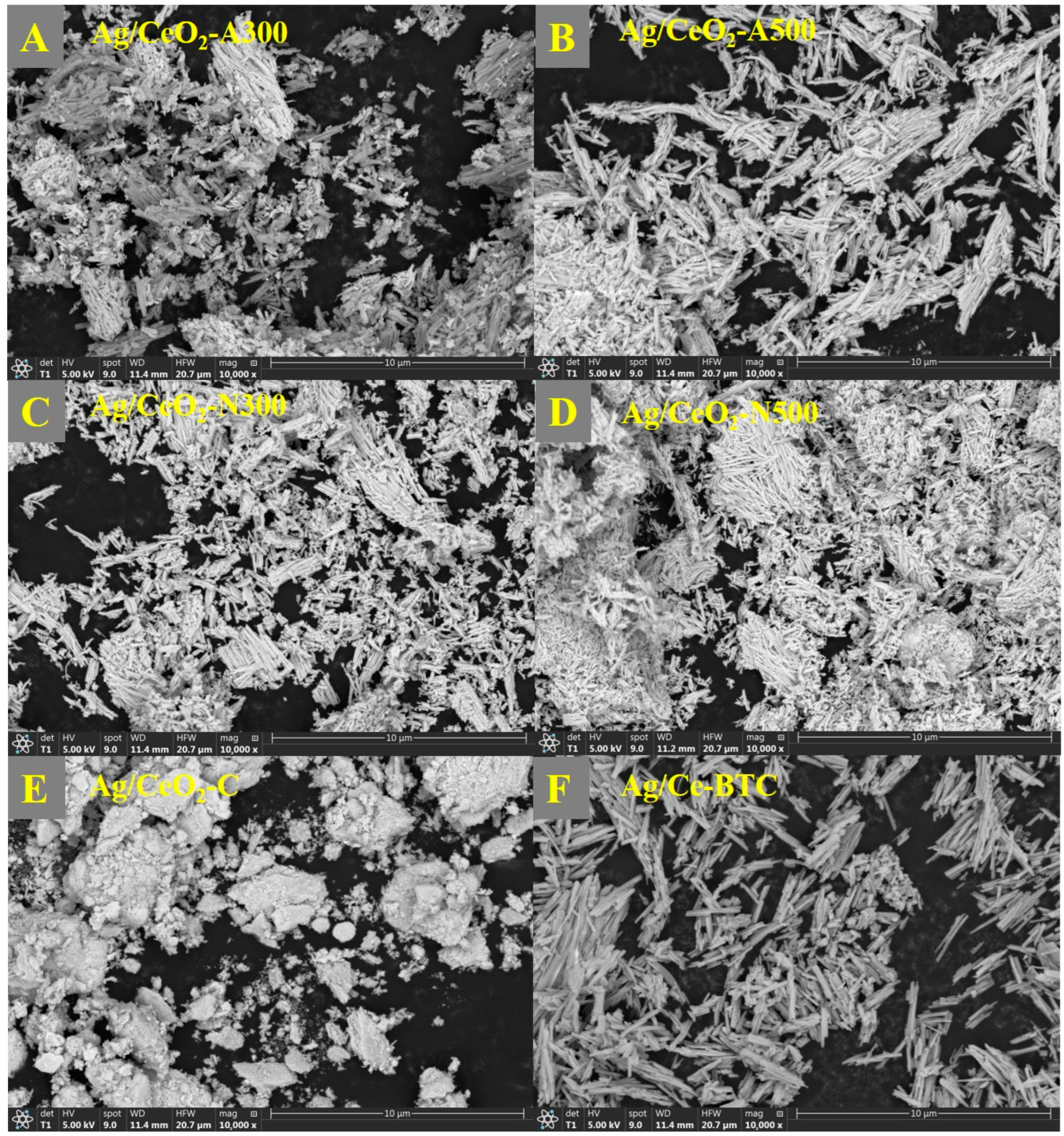

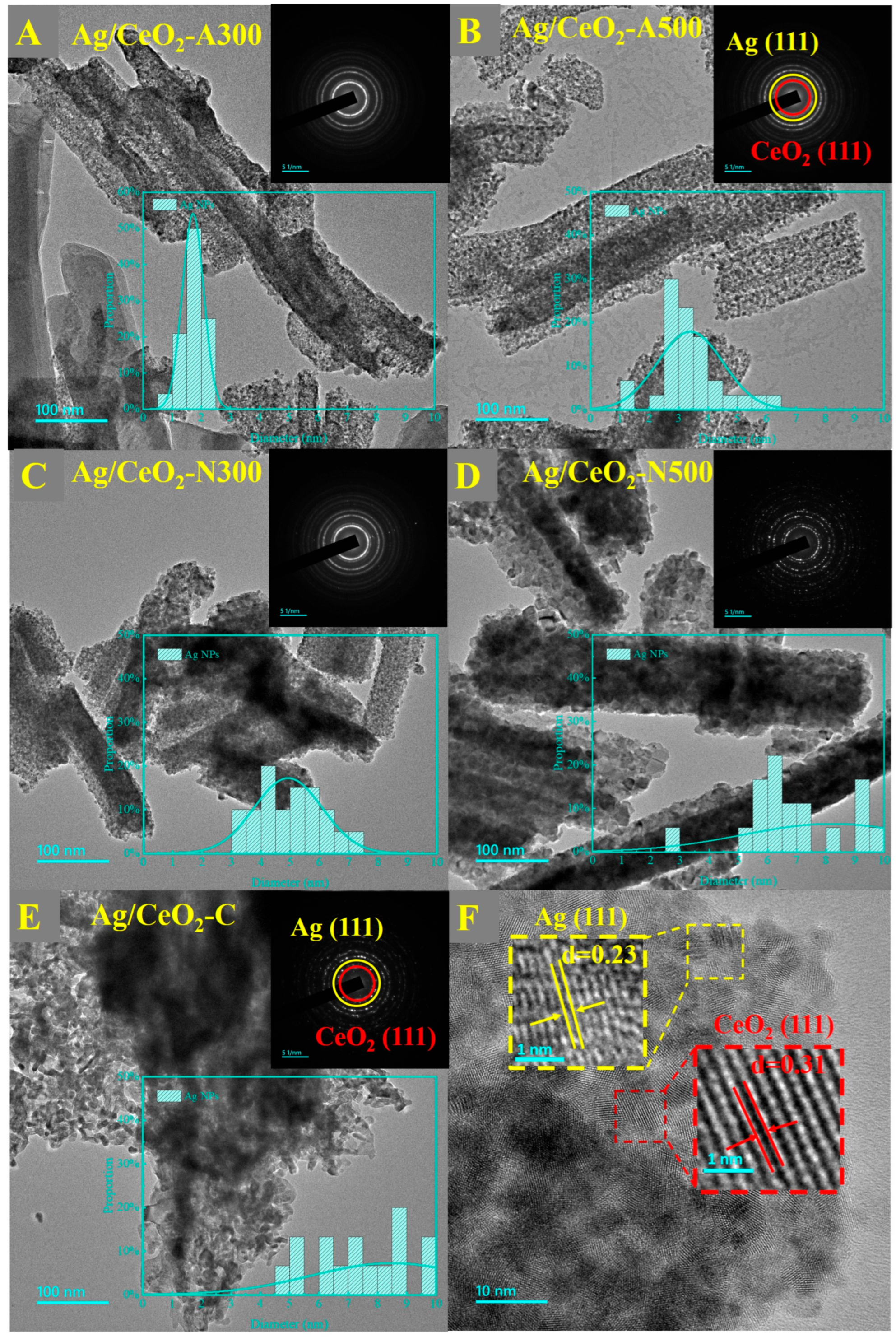

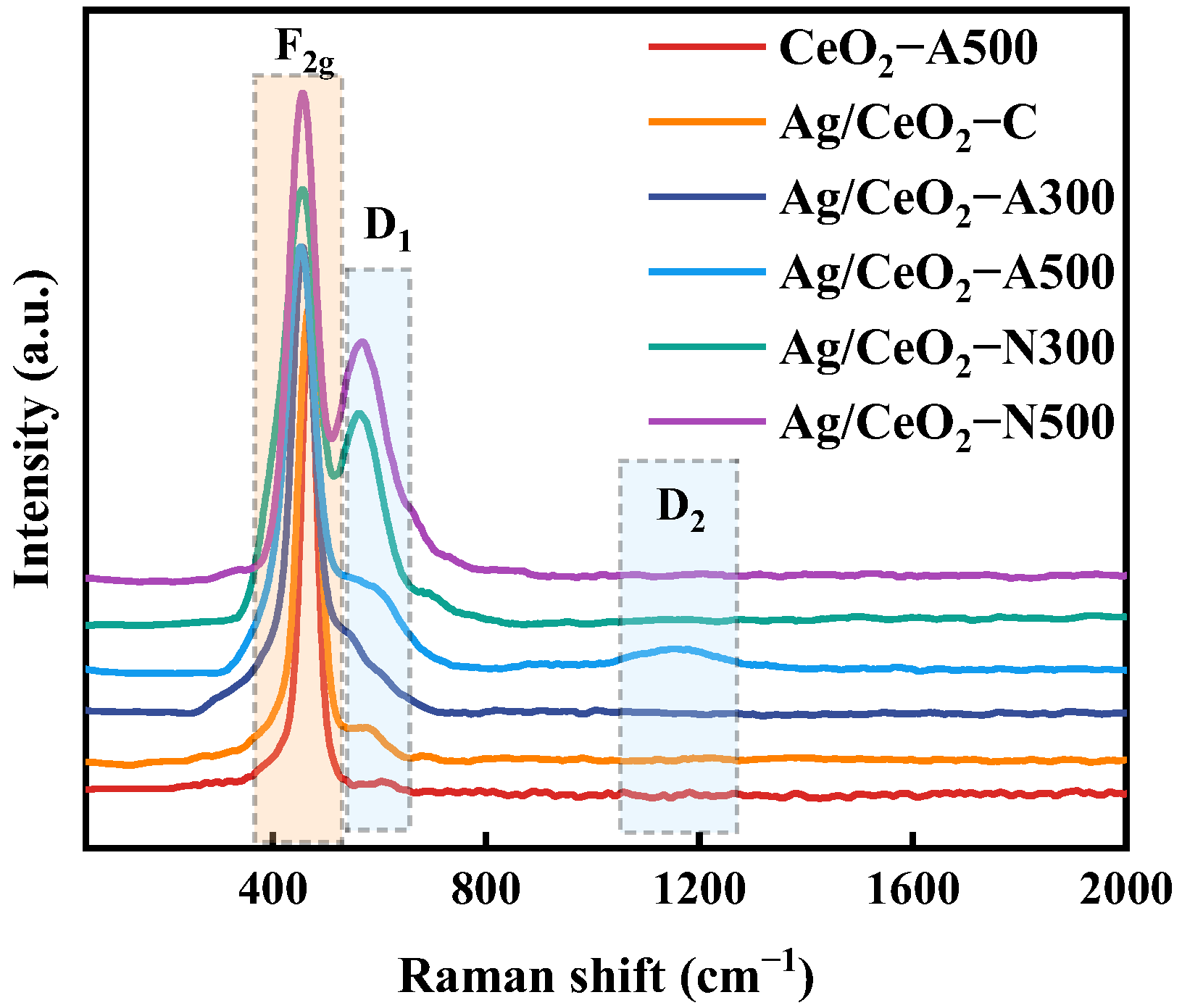

2.1. Structural Characteristics

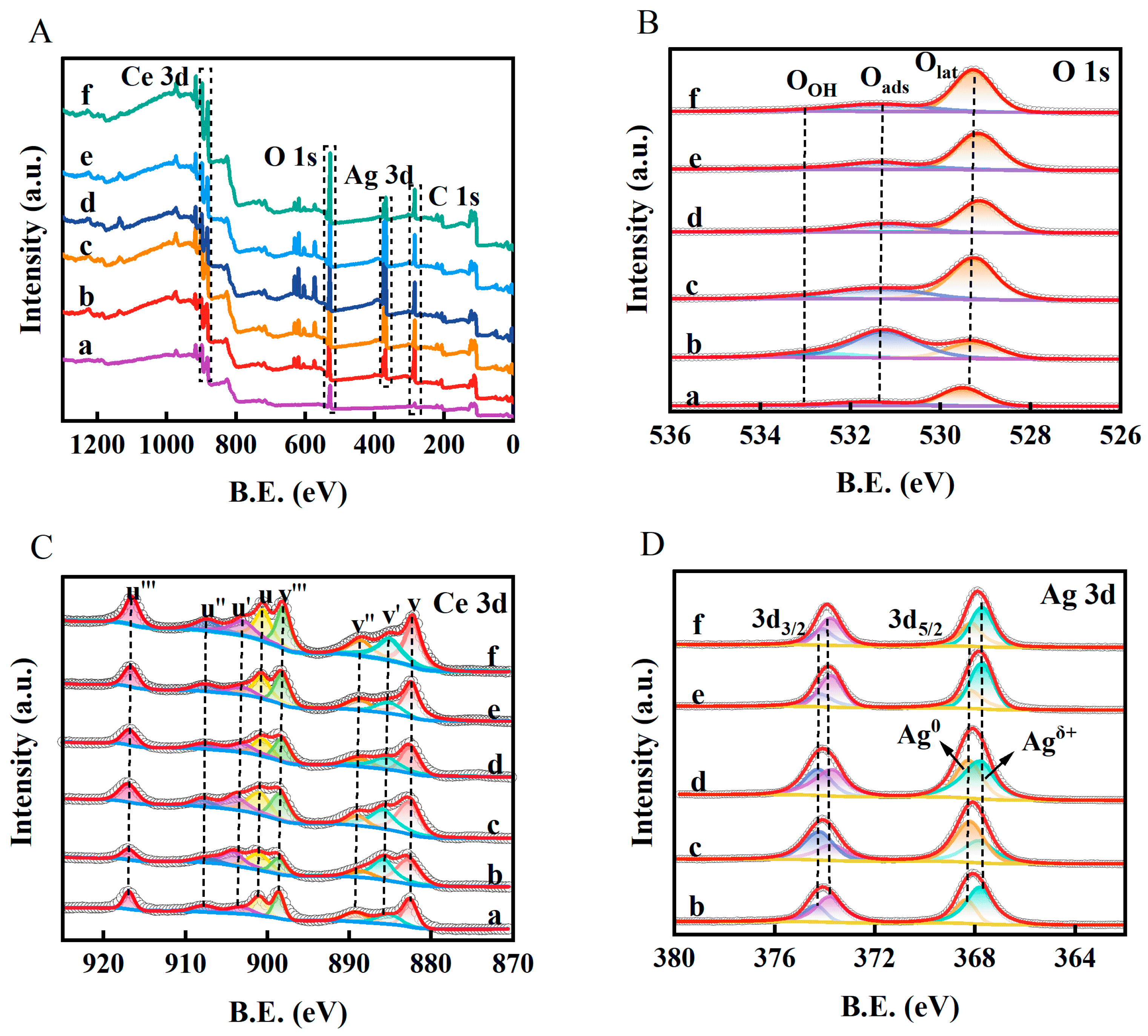

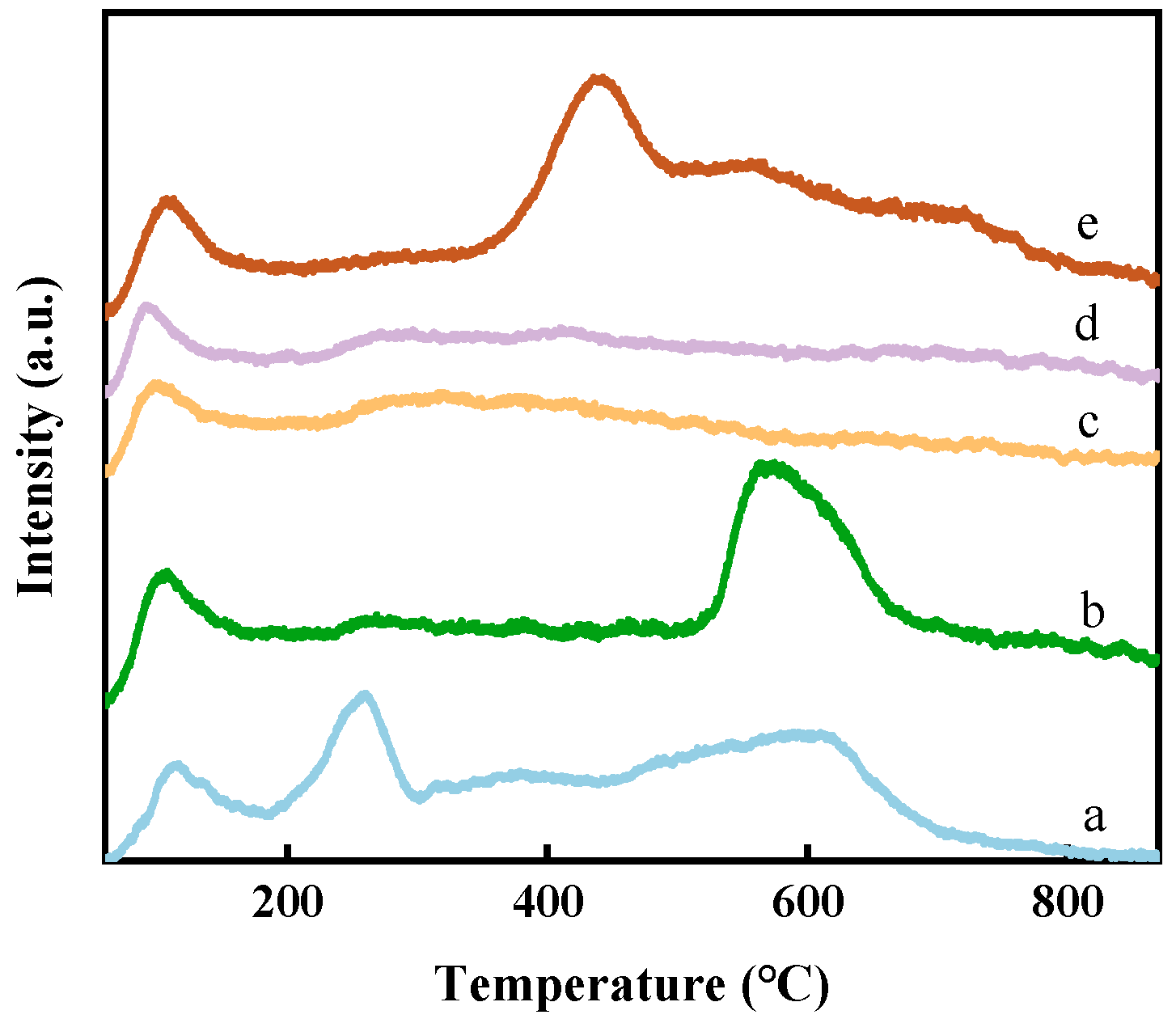

2.2. Chemical State Characterization

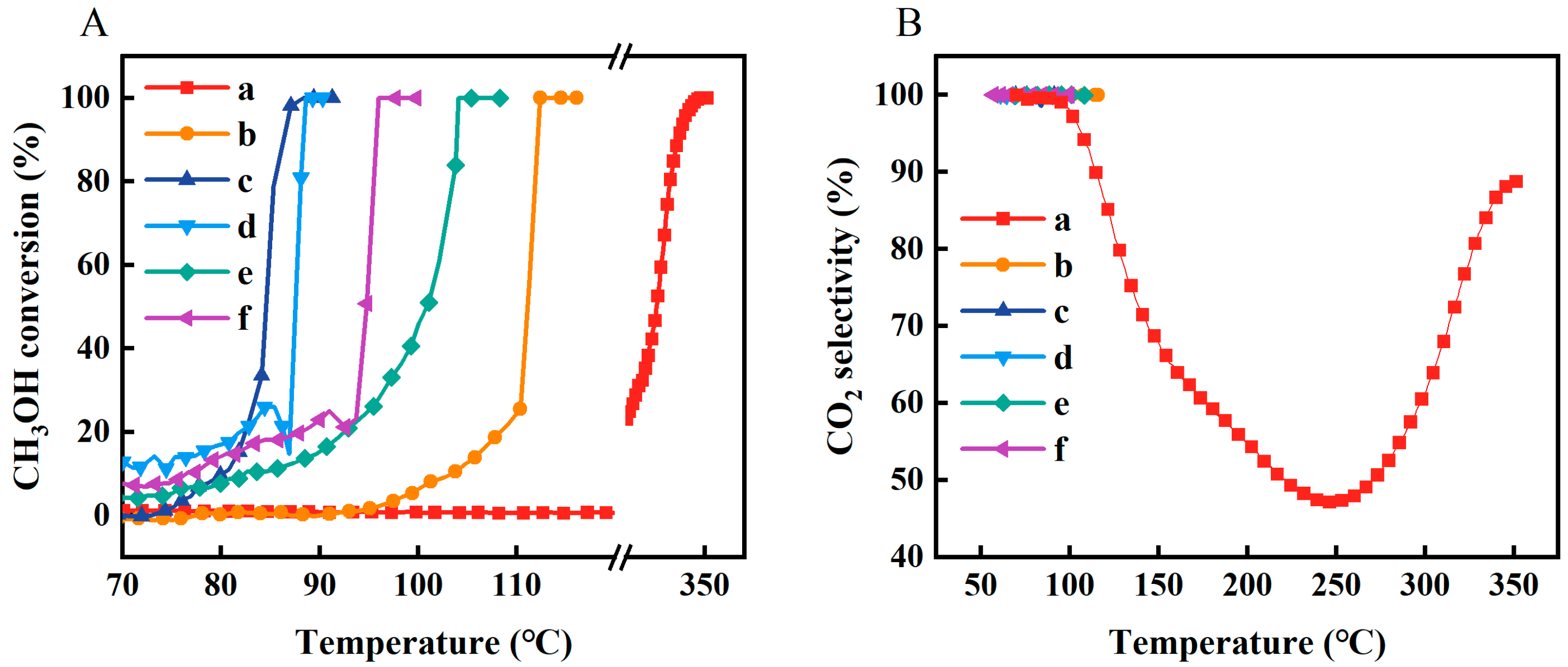

2.3. Catalytic Performance

2.4. Reaction Mechanism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Catalyst Preparation

3.2. Catalyst Characterizations

3.3. Catalytic Performance Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Verhelst, S.; Turner, J.W.G.; Sileghem, L.; Vancoillie, J. Methanol as a fuel for internal combustion engines. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019, 70, 43–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Guo, H.; Zheng, X.; Li, H.; Wang, X. Mechanism of methanol and formaldehyde emissions from methanol-fueled engines. Fuel Process. Technol. 2025, 268, 108177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Fan, C.; Qiu, L.; Qian, Y.; Wang, C.; Teng, Q.; Pan, M. Impact of methanol alternative fuel on oxidation reactivity of soot emissions from a modern CI engine. Fuel 2020, 268, 117352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera, H.; Singh, A.P.; Agarwal, A.K. Prospects of Methanol-Fuelled Carburetted Two Wheelers in Developing Countries. In Advanced Combustion Techniques and Engine Technologies for the Automotive Sector; Singh, A.P., Sharma, N., Agarwal, R., Agarwal, A.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Mu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Du, R.; Liu, S. Comprehensive study on unregulated emissions of heavy-duty SI pure methanol engine with EGR. Fuel 2022, 320, 123974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, M.N.N.; Keryakous, M.M.S.; Fawzy, M.A.; Abd El-Aziz, F.E.-Z.A.; Dawood, A.F.A.; Yassa, H.D.; Welson, N.N. The role of nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) and Nrf2 signalling in methanol-induced on brain, eye, and pancreas toxicity in rats. NeuroToxicology 2025, 110, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, P. Methanol. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 3rd ed.; Wexler, P., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hinz, A.; Larsson, P.-O.; Andersson, A. Influence of Pt Loading on Al2O3 for the Low Temperature Combustion of Methanol with and Without a Trace Amount of Ammonia. Catal. Lett. 2002, 78, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Sanwal, P.; Zhou, L.; Li, G.; Chen, Y. Effects of metal doping on the methanol deep oxidation activity of the Pd/CeO2 monolithic catalyst. Mater. Chem. Front. 2025, 9, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, R.W.; Mitchell, P.J. Exhaust-catalyst development for methanol-fueled vehicles: III. Formaldehyde oxidation. Appl. Catal. 1988, 44, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, R.W.; Mitchell, P.J. Exhaust-catalyst development for methanol-fueled vehicles: 1. A comparative study of methanol oxidation over alumina-supported catalysts containing group 9, 10, and 11 metals. Appl. Catal. 1986, 27, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, H.K.; Watkins, W.L.H.; Gandhi, H.S. Characterization of silver catalysts for the oxidation of methanol. Appl. Catal. 1987, 29, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhou, L.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, Y. Constructing Efficient CuAg Nanoalloys on Ce0.90In0.10Oδ for Methanol Deep Oxidation Catalysis at Low Temperature. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202300740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y. Research advances in volatile organic compounds catalytic removal using CeO2-based catalysts. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.G.I.; Nurfitria, R.; Anggraini, T.; Aini, Q.; Hanifah, I.R.; Nurfani, E.; Aflaha, R.; Triyana, K.; Taher, T.; Rianjanu, A. Hydrothermal synthesis of CeO2/ZnO heterojunctions for effective photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 322, 118630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, Z.; Haghighi, M.; Fatehifar, E.; Rahemi, N. Comparative synthesis and physicochemical characterization of CeO2 nanopowder via redox reaction, precipitation and sol–gel methods used for total oxidation of toluene. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2012, 7, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B.; Ismail, A.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, Y. Excellent low-temperature catalytic performance on toluene oxidation over spinel CeaMn3-aO4 catalyst derived from pyrolysis of metal organic framework. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 360, 131130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Mao, M.; Chen, L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Liu, F.; Ye, D.; Wu, J. Enhanced plasma-catalytic oxidation of methanol over MOF-derived CeO2 catalysts with exposed active sites. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Tan, W.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Feng, Y.; Ye, K.; Ma, L.; Ehrlich, S.N.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Pd-CeO2 catalyst facilely derived from one-pot generated Pd@Ce-BTC for low temperature CO oxidation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 466, 133632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bi, F.; Wang, Y.; Jia, M.; Tao, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, X. MOF-derived CeO2 supported Ag catalysts for toluene oxidation: The effect of synthesis method. Mol. Catal. 2021, 515, 111922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruwaili, H.A.; Alhumaimess, M.S.; Alsirhani, S.K.M.; Alsohaimi, I.H.; Alanazi, S.J.F.; El-Aassar, M.R.; Hassan, H.M.A. Bimetallic nanoparticles supported on Ce-BTC for highly efficient and stable reduction of nitroarenes: Towards environmental sustainability. Environ. Res. 2024, 249, 118473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Lin, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Highly efficient microwave-assisted Fenton degradation bisphenol A using iron oxide modified double perovskite intercalated montmorillonite composite nanomaterial as catalyst. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 594, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Wang, C.; Zhao, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, H. Cobalt Supported on Ce-MOF-Derived CeO2 as a Catalyst for the Efficient Epoxidation of Styrene Under Aerobic Conditions. Catal. Lett. 2024, 154, 4649–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Dong, X.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, H.; Shi, J. Mesoporous CeO2 and CuO-loaded mesoporous CeO2: Synthesis, characterization, and CO catalytic oxidation property. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 85, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, M.; Fujiwara, T.; Koga, N. Thermal Decomposition of Silver Acetate: Physico-Geometrical Kinetic Features and Formation of Silver Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 8841–8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.-Y.; Liu, X.-S.; Jia, A.-P.; Xie, Y.-L.; Lu, J.-Q.; Luo, M.-F. Enhanced Activity for CO Oxidation over Pr- and Cu-Doped CeO2 Catalysts: Effect of Oxygen Vacancies. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 15045–15051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.H.; Hass, K.C.; McBride, J.R. Raman study of CeO2: Second-order scattering, lattice dynamics, and particle-size effects. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Li, M.; Hua, Q.; Zhang, L.; Ma, Y.; Ye, B.; Huang, W. Shape-dependent interplay between oxygen vacancies and Ag–CeO2 interaction in Ag/CeO2 catalysts and their influence on the catalytic activity. J. Catal. 2012, 293, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, M.; Howe, J.; Meyer, H.M., III; Overbury, S.H. Probing Defect Sites on CeO2 Nanocrystals with Well-Defined Surface Planes by Raman Spectroscopy and O2 Adsorption. Langmuir 2010, 26, 16595–16606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Sun, M.; Li, A. Studies of the Catalytic Oxidation of CO Over Ag/CeO2 Catalyst. Catal. Lett. 2012, 142, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zou, X.; Liu, M.; Liu, W.; Wu, X.; Weng, D. Activation and deactivation of Ag/CeO2 during soot oxidation: Influences of interfacial ceria reduction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 2129–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkarev, V.V.; Kovalchuk, V.I.; d’Itri, J.L. Probing Defect Sites on the CeO2 Surface with Dioxygen. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 5341–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabchenko, M.V.; Mamontov, G.V.; Zaikovskii, V.I.; La Parola, V.; Liotta, L.F.; Vodyankina, O.V. The role of metal–support interaction in Ag/CeO2 catalysts for CO and soot oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 260, 118148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.M.; Gilbank, A.L.; García, T.; Solsona, B.; Agouram, S.; Torrente-Murciano, L. The prevalence of surface oxygen vacancies over the mobility of bulk oxygen in nanostructured ceria for the total toluene oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2015, 174–175, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Ji, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, C. Ru-incorporated Co3O4 nanoparticles from self-sacrificial ZIF-67 template as efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for rechargeable metal-air battery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 606, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shan, C.; Su, Y.; Fu, K.; Lu, S.; Han, R.; Song, C.; Ji, N.; Ma, D. Defective Ultrafine MnOx Nanoparticles Confined Within a Carbon Matrix for Low-Temperature Oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 5403–5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupin, J.-C.; Gonbeau, D.; Vinatier, P.; Levasseur, A. Systematic XPS studies of metal oxides, hydroxides and peroxides. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2000, 2, 1319–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhan, X.; Gao, R.; Chen, L.; Yu, J.; Wang, H.; Shi, H. A ZIF-8-derived copper-nitrogen co-hybrid carbon catalyst for peroxymonosulfate activation to degrade BPA. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagajyothi, P.C.; Ramaraghavulu, R.; Pavani, K.; Shim, J. Catalytic reduction of methylene blue and rhodamine B using Ce-MOF-derived CeO2 catalyst. Mater. Lett. 2023, 336, 133837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyok Ri, S.; Bi, F.; Guan, A.; Zhang, X. Manganese-cerium composite oxide pyrolyzed from metal organic framework supporting palladium nanoparticles for efficient toluene oxidation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 586, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, X.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Mao, M.; Zhang, G.; Yi, H.; Fu, M.; Ye, D.; Wu, J. Enhanced performance of low Pt loading amount on Pt-CeO2 catalysts prepared by adsorption method for catalytic ozonation of toluene. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2021, 625, 118342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hou, F.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Yang, Y. A strawsheave-like metal organic framework Ce-BTC derivative containing high specific surface area for improving the catalytic activity of CO oxidation reaction. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 259, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.; Shao, F.; Dong, X.; Dong, H.; Fang, S.; Sun, H.; Ling, Q. Effect of Ag-CeO2 interface formation during one-spot synthesis of Ag-CeO2 composites to improve their catalytic performance for CO oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 513, 145771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Lu, C.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, S.; Qian, G. Soot Oxidation over CeO2 or Ag/CeO2: Influences of Bulk Oxygen Vacancies and Surface Oxygen Vacancies on Activity and Stability of the Catalyst. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 2018, 2944–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Huang, X.; Li, G. Fabrication of Ag–CeO2 core–shell nanospheres with enhanced catalytic performance due to strengthening of the interfacial interactions. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 10480–10487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scirè, S.; Riccobene, P.M.; Crisafulli, C. Ceria supported group IB metal catalysts for the combustion of volatile organic compounds and the preferential oxidation of CO. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 101, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.C.; Yao, Y.F.Y. Ceria in automotive exhaust catalysts: I. Oxygen storage. J. Catal. 1984, 86, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Yu, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J. Support effects on the structure and catalytic activity of mesoporous Ag/CeO2 catalysts for CO oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 229, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wang, D.; Xue, W.; Dou, B.; Wang, H.; Hao, Z. Investigation of Formaldehyde Oxidation over Co3O4−CeO2 and Au/Co3O4−CeO2 Catalysts at Room Temperature: Effective Removal and Determination of Reaction Mechanism. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 3628–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, M.; Haensch, M.; Carstens, J.; Wittstock, G.; Weissmüller, J. Electrocatalytic methanol oxidation with nanoporous gold: Microstructure and selectivity. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 17839–17848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qu, Z.; Yu, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Effects of pretreatment atmosphere and silver loading on the structure and catalytic activity of Ag/SBA-15 catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2013, 370, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-C.; Li, X.-C.; Xie, Z.-W.; Yuan, C.-Y.; Wang, D.-J.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, X.-Y.; Dong, H.; Liu, H.-C.; Zhang, Y.-W. Strong metal-support interactions between highly dispersed Cu+ species and ceria via mix-MOF pyrolysis toward promoted water-gas shift reaction. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 91, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Song, J.; Song, X.; Yan, Z.; Zeng, H. Ag/white graphene foam for catalytic oxidation of methanol with high efficiency and stability. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 6679–6684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, H.-B.; Lin, G.-D.; Xiong, Z.-T. Study of Ag/La0.6Sr0.4MnO3 catalysts for complete oxidation of methanol and ethanol at low concentrations. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2000, 24, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Cai, G.; Zheng, Y.; Wei, K. A study of barium doped Pd/Al2O3-Ce0.3Zr0.7O2 catalyst for complete methanol oxidation. Catal. Commun. 2012, 27, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klissurski, D.; Mitov, I.; Ivanov, K.; Tyuliev, G.; Dimitrov, D.; Chakarova, K.; Uzunov, I. Total catalytic oxidation of methanol on Au/Fe2O3 catalysts. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2010, 100, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lin, C.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, P. Review on noble metal-based catalysts for formaldehyde oxidation at room temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 475, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Yang, W.; Wang, C.; Xiong, S.; Cao, X.; Peng, Y.; Si, W.; Weng, Y.; Xue, M.; Li, J. Roles of Oxygen Vacancies in the Bulk and Surface of CeO2 for Toluene Catalytic Combustion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 12684–12692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattel, S.; Yan, B.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.G.; Liu, P. Optimizing Binding Energies of Key Intermediates for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol over Oxide-Supported Copper. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 12440–12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wu, C.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Wu, X. Efficient Catalysts for Low-Temperature Methanol Oxidation: Mn-Coated Nanospherical CeO2. Catal. Lett. 2023, 153, 2471–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen, P.K.; Labadini, D.; Hafiz, S.S.; Gokalp, S.; Wolff, E.P.; Martell, S.M.; Foster, M. DRIFTS investigation of methanol oxidation on CeO2 nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 554, 149518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, S.; Marie, O.; Bazin, P.; Daturi, M.; Verdier, S.; Harlé, V. Investigation of Methanol Oxidation over Au/Catalysts Using Operando IR Spectroscopy: Determination of the Active Sites, Intermediate/Spectator Species, and Reaction Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10832–10841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.B.; Lee, D.K.; Sandoval, M.J.; Bell, A.T. Infrared Studies of the Mechanism of Methanol Decomposition on Cu/SiO2. J. Catal. 1994, 150, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Crystal Size (nm) | SBET (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag/Ce-BTC | / | 3.74 | 0.005 | 5.34 |

| Ag/CeO2-A300 | 2.0 | 29.92 | 0.033 | 4.35 |

| Ag/CeO2-A500 | 12.9 | 86.62 | 0.108 | 5.03 |

| Ag/CeO2-N300 | 6.0 | 58.72 | 0.055 | 3.82 |

| Ag/CeO2-N500 | 12.7 | 24.01 | 0.038 | 6.41 |

| Ag/CeO2-C | 9.8 | 47.06 | 0.139 | 11.87 |

| CeO2-A500 | / | 64.62 | 0.083 | 5.13 |

| Samples | ID1/ IF2g | Oads/Olat | Ce3+/(Ce3+ + Ce4+) | Ag0/Agδ+ | H2 Consumption (μmol/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CeO2-A500 | / | 0.327 | 0.338 | / | / |

| Ag/CeO2-A300 | / | 2.132 | 0.389 | 0.469 | / |

| Ag/CeO2-A500 | 1.168 | 0.488 | 0.310 | 1.541 | 182,428.3 |

| Ag/CeO2-N300 | 0.507 | 0.430 | 0.307 | 0.737 | 181,819.8 |

| Ag/CeO2-N500 | 1.067 | 0.364 | 0.161 | 0.518 | 180,791.8 |

| Ag/CeO2-C | 0.128 | 0.386 | 0.244 | 0.743 | 181,603.8 |

| Catalysts | Methanol Concentration (ppm) | Oxygen Concentration (%) | T50 (°C) | T95 (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu40Ag60/Ce0.90In0.10Oδ | 200 | 2 | 115 | 145–150 | [13] |

| Ag/γ-Al2O3 | 2000 | 10 | 110 | 180 | [53] |

| 6%Ag/γ-Al2O3 | 2000 | 1 | 135 | 175 | [54] |

| Pd/Al2O3-Ce0.3Zr0.7O2 | 2000 | 1 | 56 | 80–90 | [55] |

| Au/Fe2O3 | 40,000 | 20 | 100 | 150 | [56] |

| Ag/CeO2-A500 | 5000 | 10 | 85 | 87 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bao, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, P.; Wang, K.; Luo, D.; Geng, L.; Chen, Z. Influence of Ag/CeO2-Supported Catalysts Derived from Ce-MOFs on Low-Temperature Oxidation of Unregulated Methanol Emissions from Methanol Engines. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121165

Bao Z, Li Z, Chen H, Zhang P, Wang K, Luo D, Geng L, Chen Z. Influence of Ag/CeO2-Supported Catalysts Derived from Ce-MOFs on Low-Temperature Oxidation of Unregulated Methanol Emissions from Methanol Engines. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121165

Chicago/Turabian StyleBao, Zhongqiang, Zhenguo Li, Hao Chen, Peng Zhang, Kaifeng Wang, Ding Luo, Limin Geng, and Zhanming Chen. 2025. "Influence of Ag/CeO2-Supported Catalysts Derived from Ce-MOFs on Low-Temperature Oxidation of Unregulated Methanol Emissions from Methanol Engines" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121165

APA StyleBao, Z., Li, Z., Chen, H., Zhang, P., Wang, K., Luo, D., Geng, L., & Chen, Z. (2025). Influence of Ag/CeO2-Supported Catalysts Derived from Ce-MOFs on Low-Temperature Oxidation of Unregulated Methanol Emissions from Methanol Engines. Catalysts, 15(12), 1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121165