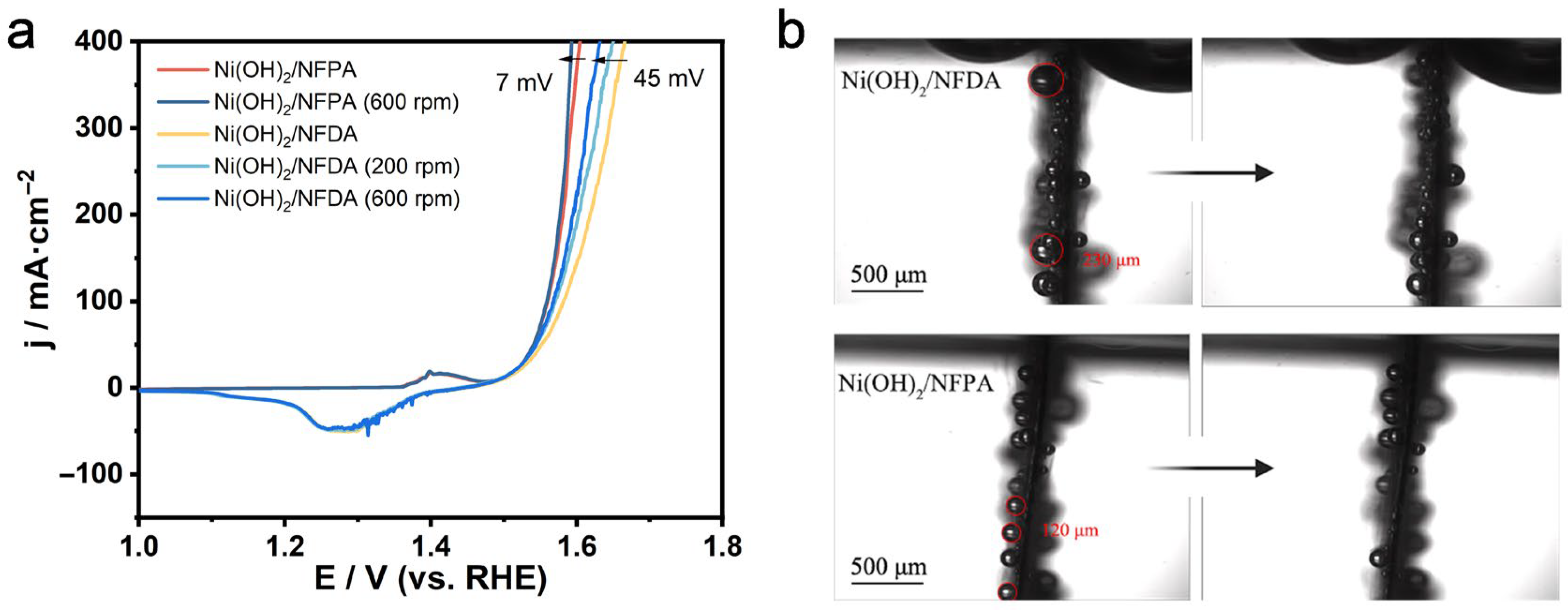

Facet-Engineered Parallel Ni(OH)2 Arrays for Enhanced Bubble Dynamics and Durable Alkaline Seawater Electrolysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

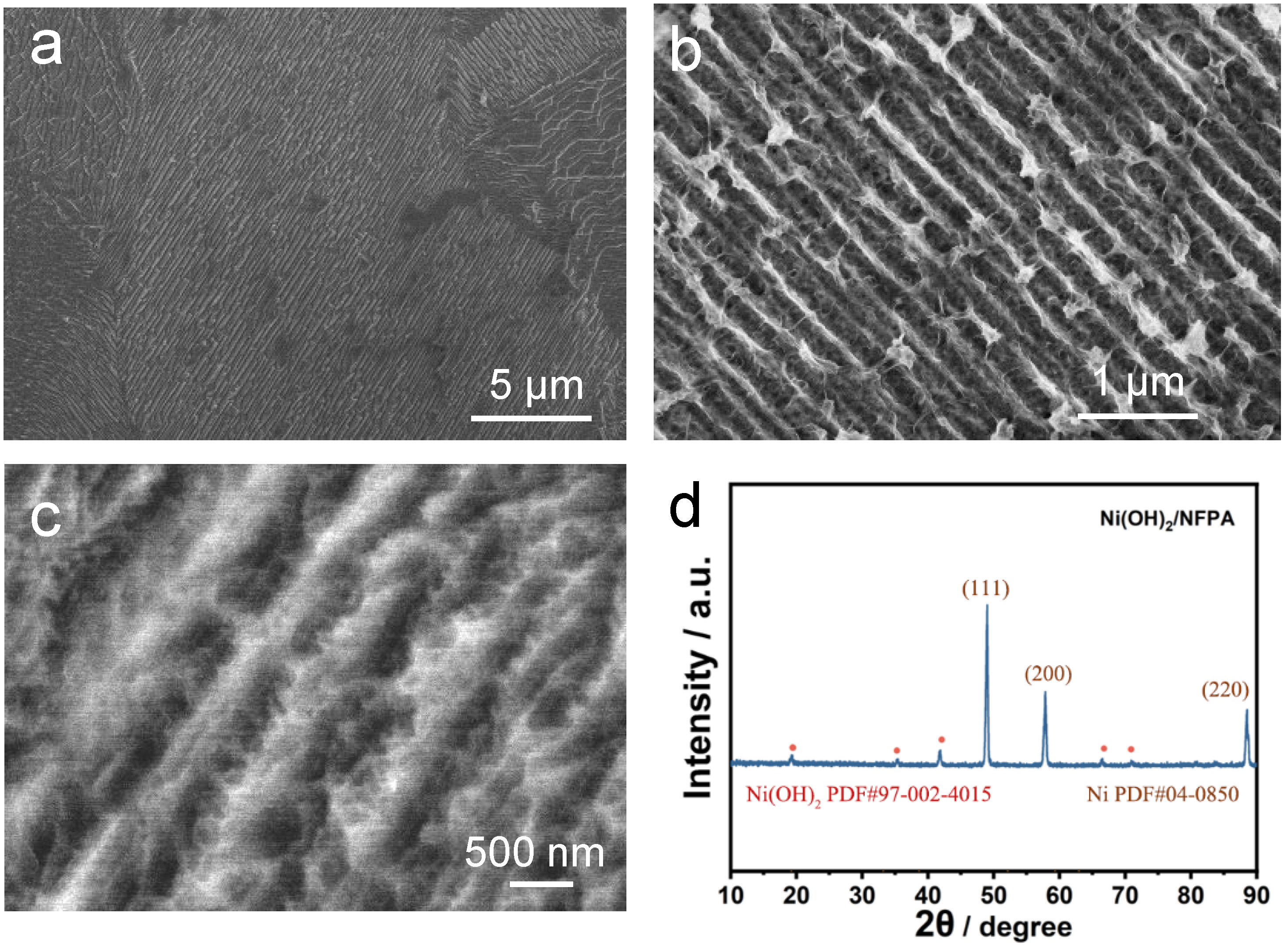

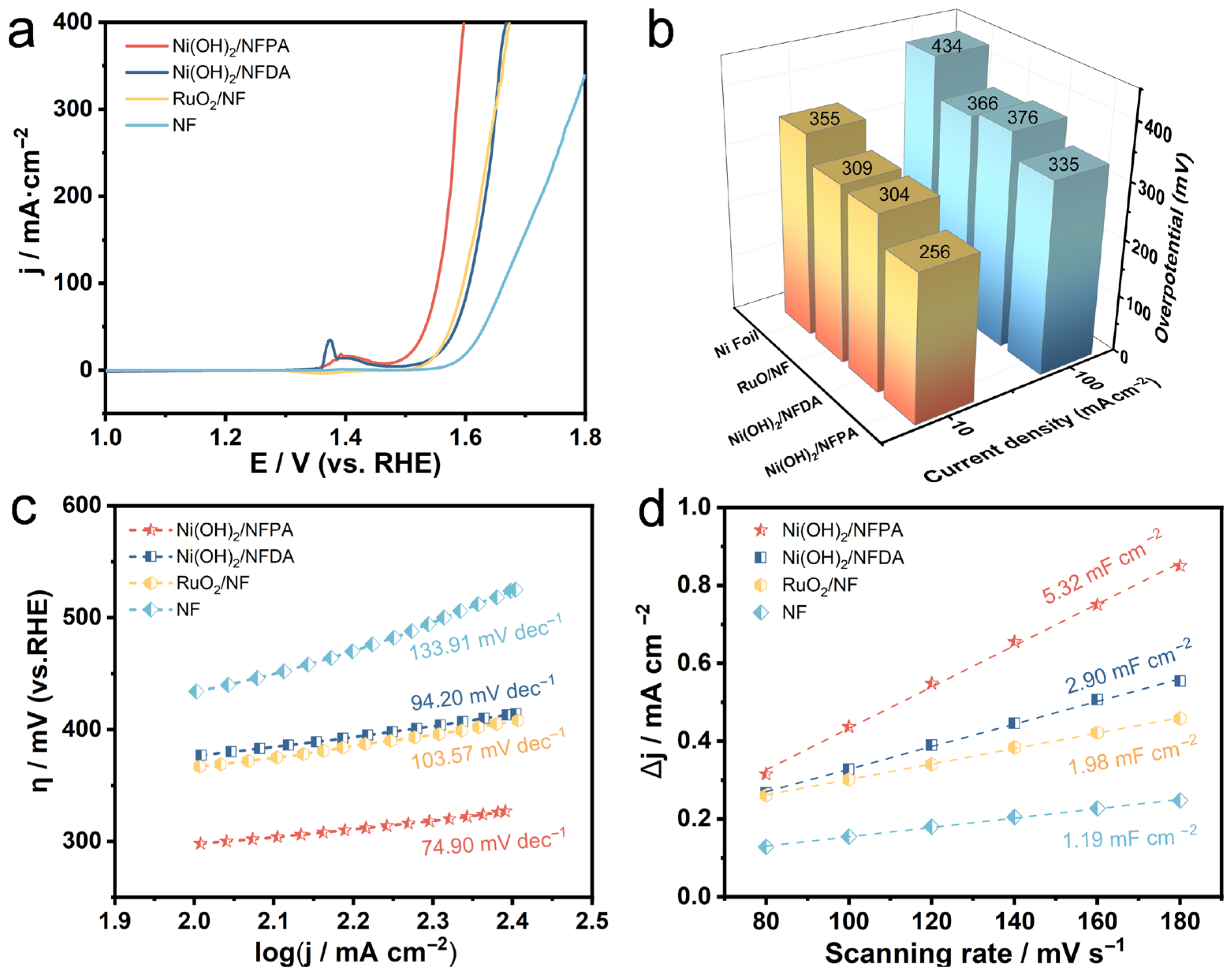

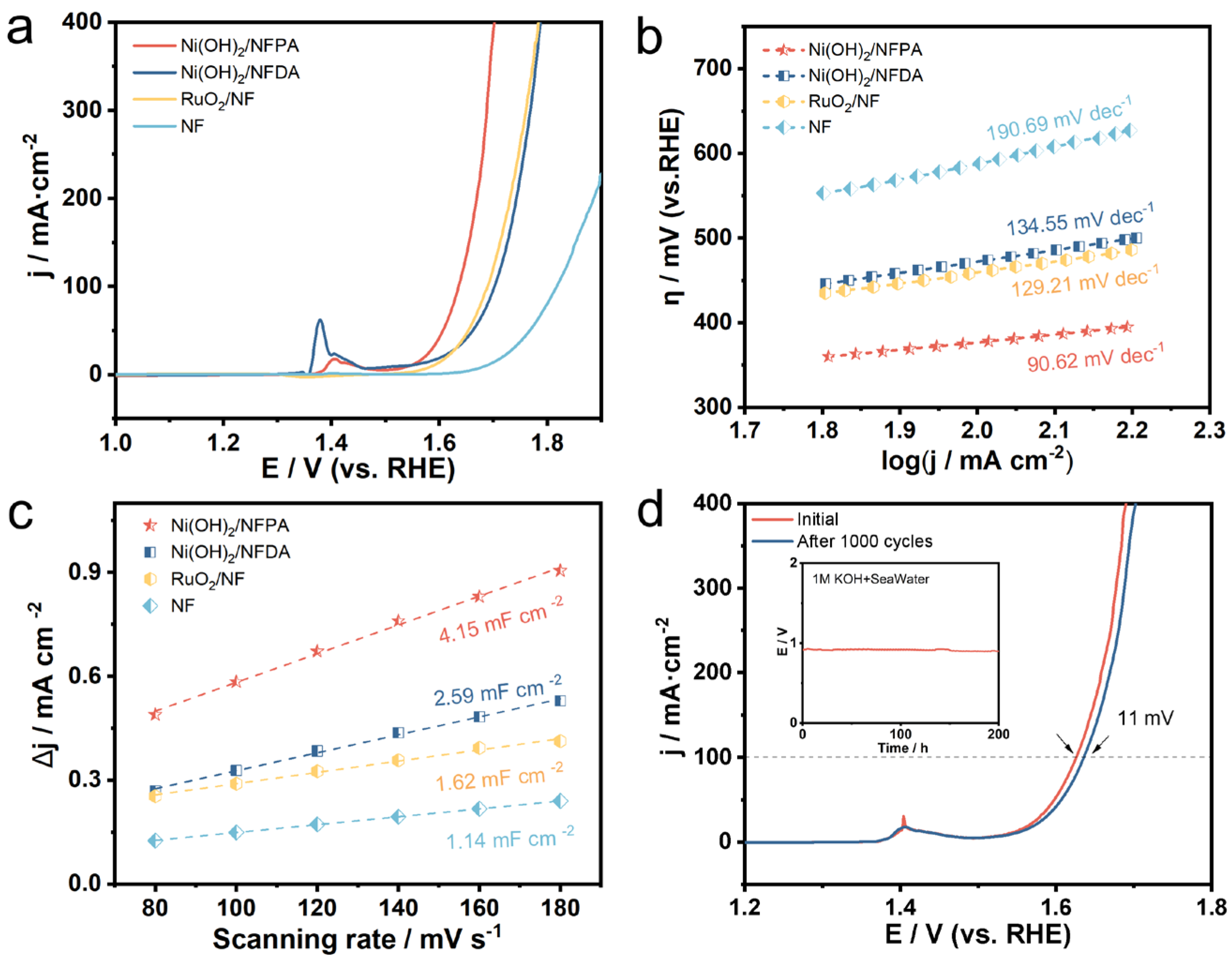

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemical and Materials

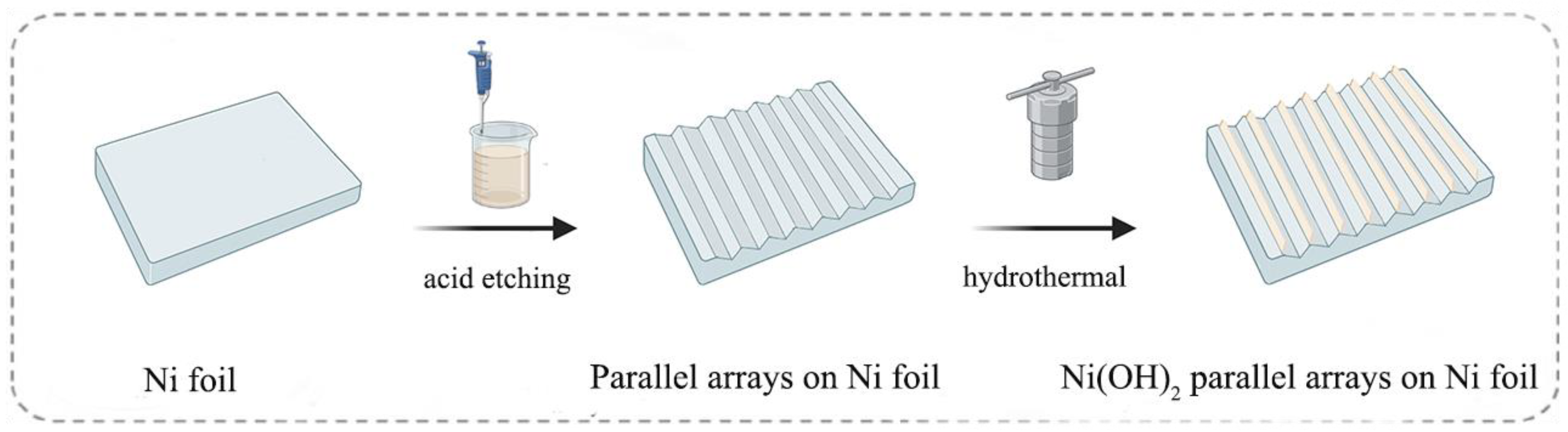

3.2. Synthesis of NFPA

3.3. Synthesis of Ni(OH)2/NFPA and Ni(OH)2/NFDA

3.4. Materials Characterization

3.5. Electrochemical Measurement

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walter, M.G.; Warren, E.L.; McKone, J.R.; Boettcher, S.W.; Mi, Q.; Santori, E.A.; Lewis, N.S. Solar water splitting cells. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6446–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, M.S.; Thomas, I.L. Alternative energy technologies. Nature 2001, 414, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Song, H.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Shai, X.; Miao, L. Water dissociation kinetic-oriented design of nickel sulfides via tailored dual sites for efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2008578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Kuo, T.; Li, Y.; Qi, M.; Chen, G.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Chen, H.M. Emerging dynamic structure of electrocatalysts unveiled by in situ X-ray diffraction/absorption spectroscopy. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 1928–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, I.; Shipman, M.A.; Symes, M.D. Earth-abundant catalysts for electrochemical and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, X.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, G.; Huang, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, R.; Nuckolls, C.; Ni, H. An effective hybrid electrocatalyst for the alkaline HER: Highly dispersed Pt sites immobilized by a functionalized NiRu-hydroxide. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 269, 118824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Hu, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Chen, F.; Hu, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Deng, Y.; Qin, Z. Heterogeneous lamellar-edged Fe-Ni(OH)2/Ni3S2 nanoarray for efficient and stable seawater oxidation. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jin, B.; Vasileff, A.; Jiao, Y.; Qiao, S. Interfacial nickel nitride/sulfide as a bifunctional electrode for highly efficient overall water/seawater electrolysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 8117–8121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, W.; Dong, J.; Lu, X.F.; Lou, X.W.D. Intramolecular electronic coupling in porous iron cobalt (oxy) phosphide nanoboxes enhances the electrocatalytic activity for oxygen evolution. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 3348–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Qin, R.; Ji, P.; Pu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Lin, C.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, H.; Li, W.; Mu, S. Synergistic coupling of Ni nanoparticles with Ni3C nanosheets for highly efficient overall water splitting. Small 2020, 16, 2001642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Lou, X.W. Unveiling the activity origin of electrocatalytic oxygen evolution over isolated Ni atoms supported on a N-doped carbon matrix. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1904548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Z.; Vasileff, A.; Qiao, S.Z. NiO as a bifunctional promoter for RuO2 toward superior overall water splitting. Small 2018, 14, 1704073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Sheng, W.; Zhuang, Z.; Fang, Q.; Gu, S.; Jiang, J.; Yan, Y. Efficient water oxidation using nanostructured α-nickel-hydroxide as an electrocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7077–7084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Fan, K.; Zhang, P.; Sun, L. Selective electrochemical alkaline seawater oxidation catalyzed by cobalt carbonate hydroxide nanorod arrays with sequential proton-electron transfer properties. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yu, L.; Zhang, F.; McElhenny, B.; Luo, D.; Karim, A.; Chen, S.; Ren, Z. Heterogeneous bimetallic phosphide Ni2P-Fe2P as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for water/seawater splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2006484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresp, S.; Dionigi, F.; Klingenhof, M.; Strasser, P. Direct electrolytic splitting of seawater: Opportunities and challenges. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yu, L.; Zhu, Q.; McElhenny, B.; Zhang, F.; Wu, C.; Xing, X.; Bao, J.; Chen, S.; Ren, Z. Boron-modified cobalt iron layered double hydroxides for high efficiency seawater oxidation. Nano Energy 2021, 83, 105838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionigi, F.; Reier, T.; Pawolek, Z.; Gliech, M.; Strasser, P. Design criteria, operating conditions, and nickel-iron hydroxide catalyst materials for selective seawater electrolysis. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 962–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, A.R.; Kumar, A.; Lee, J.; Yang, T.; Na, S.; Lee, J.; Luo, Y.; Liu, X.; Hwang, Y.; Liu, Y. Stable complete seawater electrolysis by using interfacial chloride ion blocking layer on catalyst surface. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 24501–24514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Ji, P.; Wang, P.; Tan, X.; Chen, L.; Mu, S. Spherical Ni3S2/Fe-NiPx magic cube with ultrahigh water/seawater oxidation efficiency. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elrahim, A.G.; Chun, D.M. Kinetically induced one-step heterostructure formation of Co3O4-Ni(OH)2-graphene ternary nanocomposites to enhance oxygen evolution reactions. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 906, 164159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, X.; Sendeku, M.G.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Duan, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, W. Phosphate-decorated Ni3Fe-LDHs@CoPx nanoarray for near-neutral seawater splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 460, 141413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Liu, W.; Jiang, M.; Wang, W.; Kang, Q.; Wang, P.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, F. Preferential adsorption of hydroxide ions onto partially crystalline NiFe-layered double hydroxides leads to efficient and selective OER in alkaline seawater. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 4630–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhu, Q.; Song, S.; McElhenny, B.; Wang, D.; Wu, C.; Qin, Z.; Bao, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, S. Non-noble metal-nitride based electrocatalysts for high-performance alkaline seawater electrolysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, X. Design of a multilayered oxygen-evolution electrode with high catalytic activity and corrosion resistance for saline water splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2101820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Kuang, P.; Wang, L.; Yu, J. Hierarchical porous nickel supported NiFeOxHy nanosheets for efficient and robust oxygen evolution electrocatalyst under industrial condition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 299, 120668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wang, T.; He, S.; Li, B.; Wang, K.; Chen, Q.; Du, Z.; Ai, W.; Huang, W. Mountain-Shaped Nickel Nanostripes Enabled by Facet Engineering of Nickel Foam: A New Platform for High-Current-Density Water Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2311854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Assresahegn, B.D.; Abdellah, A.; Miner, L.; Al Hejami, A.; Zaker, N.; Gaudet, J.; Roue, L.; Botton, G.A.; Beauchemin, D. Role of Ir decoration in activating a multiscale fractal surface in porous Ni for the oxygen evolution reaction. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 1726–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Tian, B.; Gao, X.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, S.; Song, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Sun, X. Copper nanowire with enriched high-index facets for highly selective CO2 reduction. SmartMat 2022, 3, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swesi, A.T.; Masud, J.; Nath, M. Nickel selenide as a high-efficiency catalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, T.; Stühmeier, B.M.; Gasteiger, H.A.; El-Sayed, H.A. Capabilities and limitations of rotating disk electrodes versus membrane electrode assemblies in the investigation of electrocatalysts. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, O.; Park, S.; Eggebeen, J.J.; Koper, M.T. Non-kinetic effects convolute activity and tafel analysis for the alkaline oxygen evolution reaction on NiFeOOH electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202216477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Xue, Z.; Liu, C.; Qiao, X.; Liu, L.; Huang, C.; Liu, K.; Li, X.; Lu, Z.; Wang, T. General strategy to optimize gas evolution reaction via assembled striped-pattern superlattices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 142, 1857–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Kong, X.; Shi, R.; Waterhouse, G.I.; Wen, L.; Zhang, T. Underwater superaerophobic Ni nanoparticle-decorated nickel-molybdenum nitride nanowire arrays for hydrogen evolution in neutral media. Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varble, N.; Trylesinski, G.; Xiang, J.; Snyder, K.; Meng, H. Identification of vortex structures in a cohort of 204 intracranial aneurysms. J. R. Soc. Interface 2017, 14, 20170021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Liu, H.; Jia, B.; Qu, X.; Qin, M. Facet-Engineered Parallel Ni(OH)2 Arrays for Enhanced Bubble Dynamics and Durable Alkaline Seawater Electrolysis. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121144

Liu L, Liu H, Jia B, Qu X, Qin M. Facet-Engineered Parallel Ni(OH)2 Arrays for Enhanced Bubble Dynamics and Durable Alkaline Seawater Electrolysis. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121144

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Luan, Hongru Liu, Baorui Jia, Xuanhui Qu, and Mingli Qin. 2025. "Facet-Engineered Parallel Ni(OH)2 Arrays for Enhanced Bubble Dynamics and Durable Alkaline Seawater Electrolysis" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121144

APA StyleLiu, L., Liu, H., Jia, B., Qu, X., & Qin, M. (2025). Facet-Engineered Parallel Ni(OH)2 Arrays for Enhanced Bubble Dynamics and Durable Alkaline Seawater Electrolysis. Catalysts, 15(12), 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121144