Hollow ZnO Nanofibers for Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

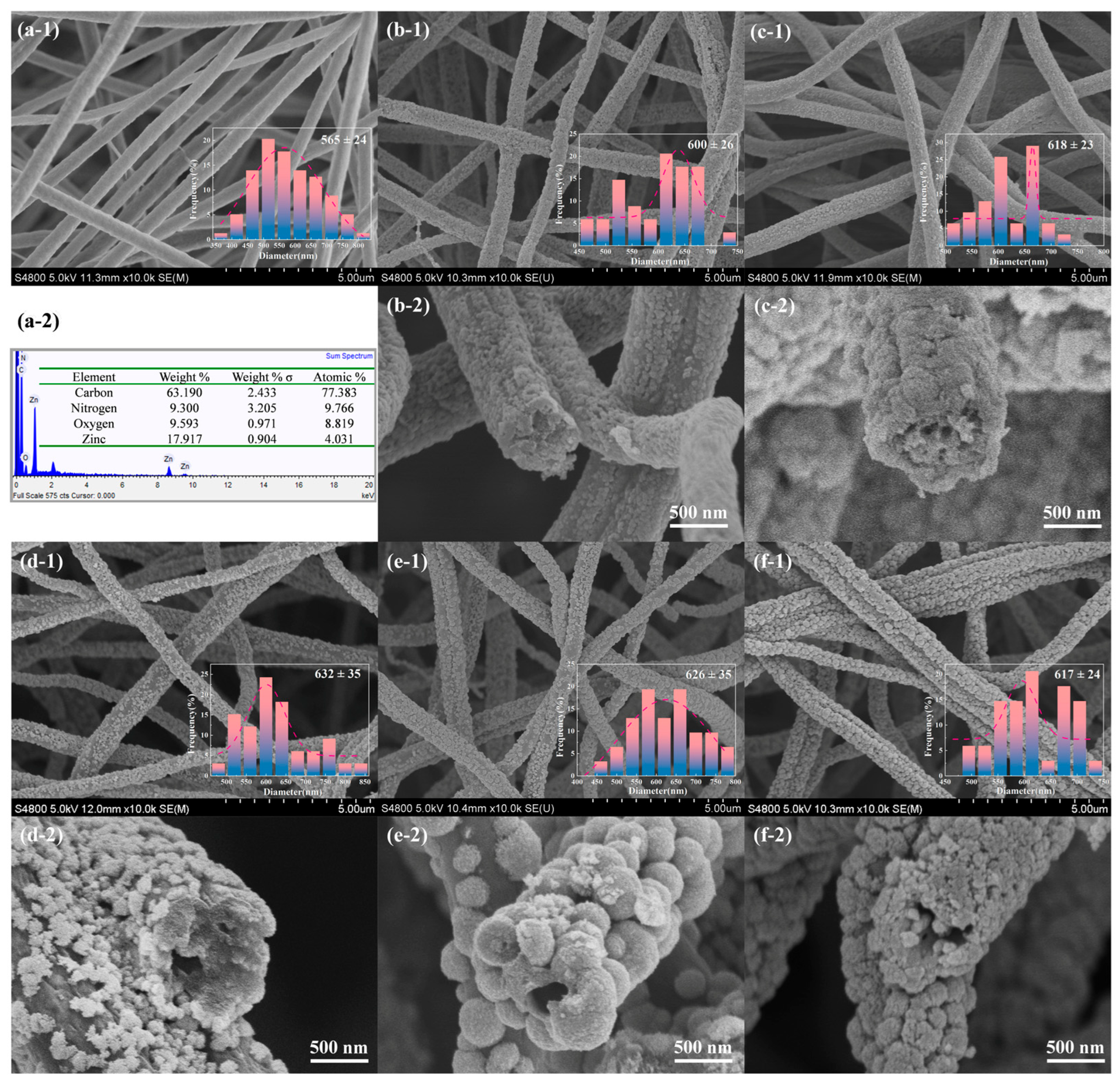

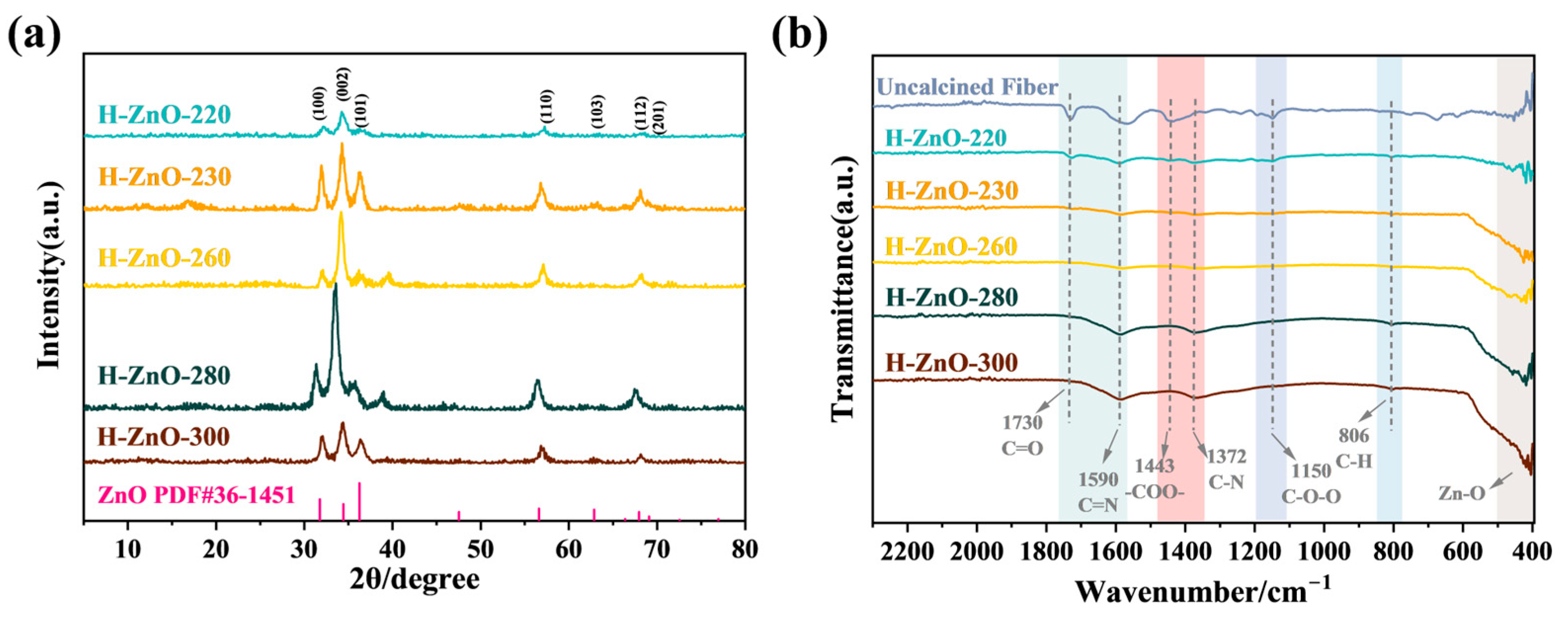

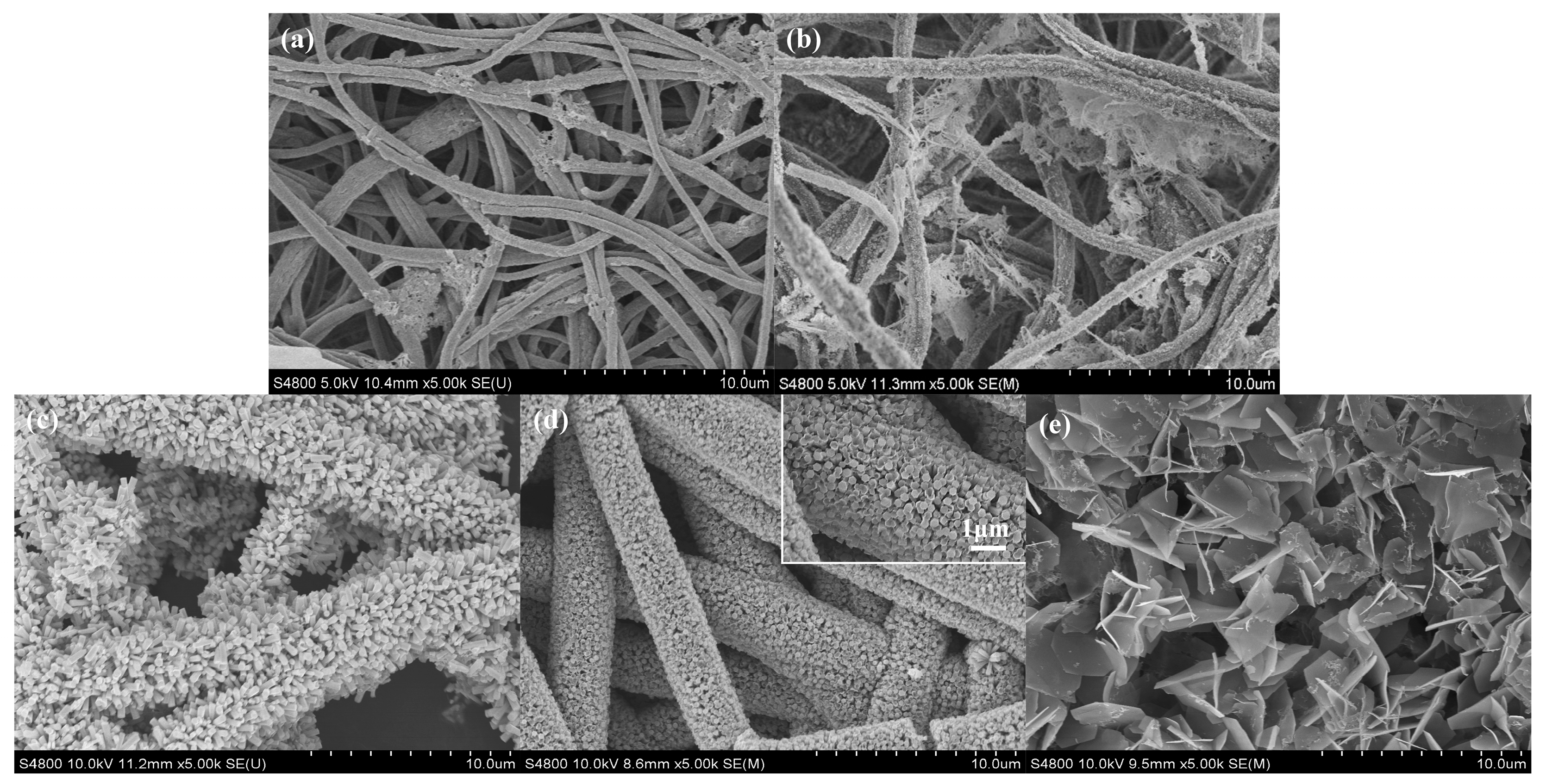

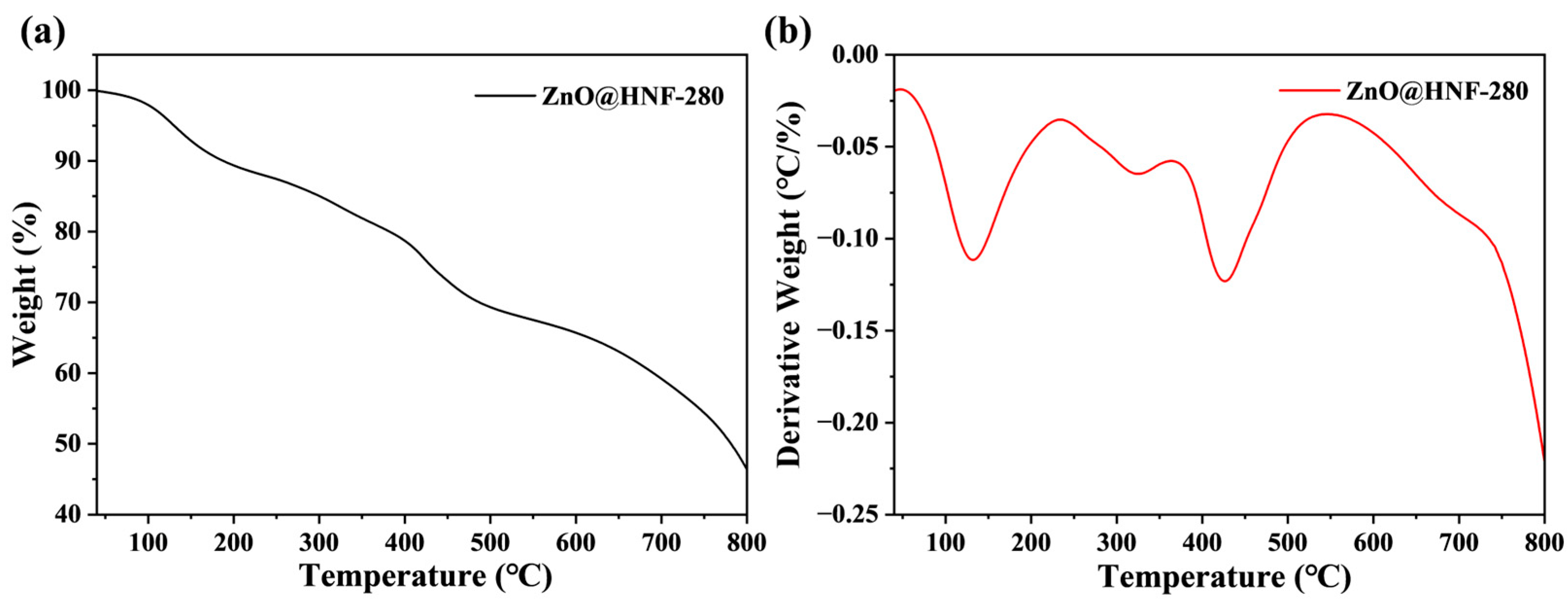

2.1. Morphology and Structure Characterization

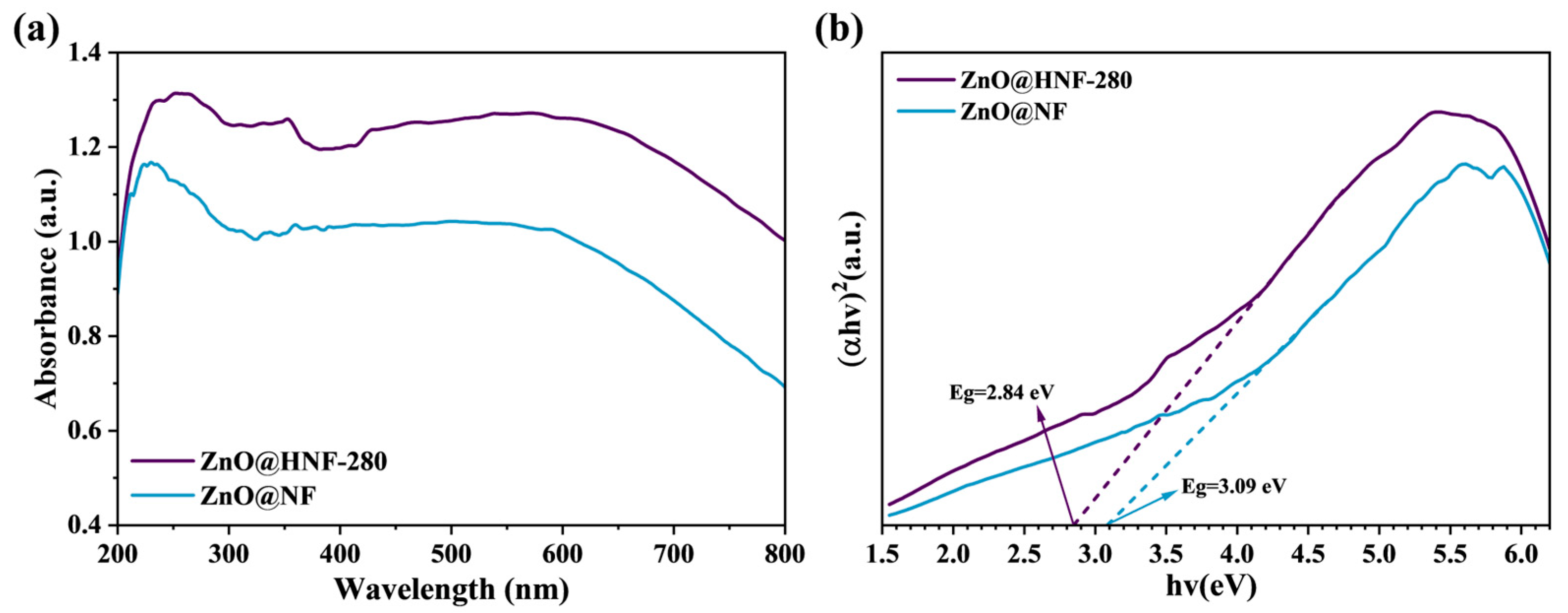

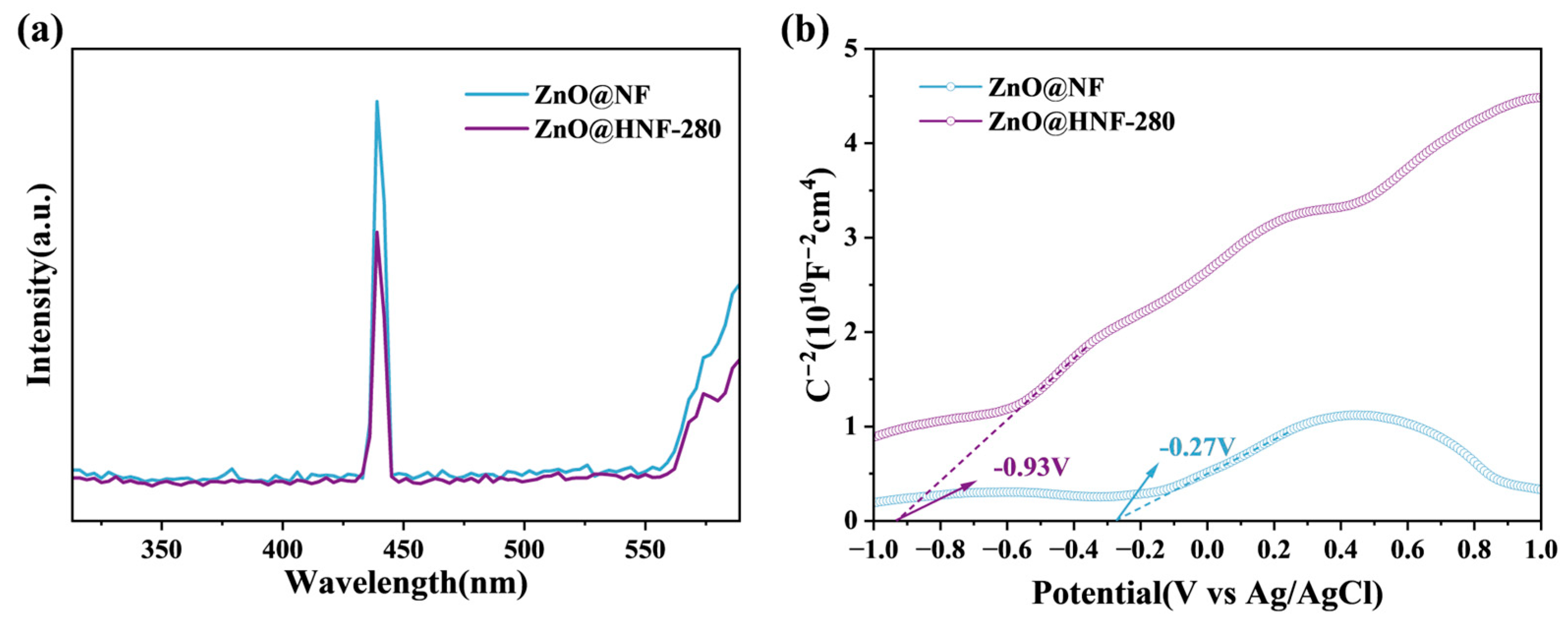

2.2. Analysis of Optical Characteristics

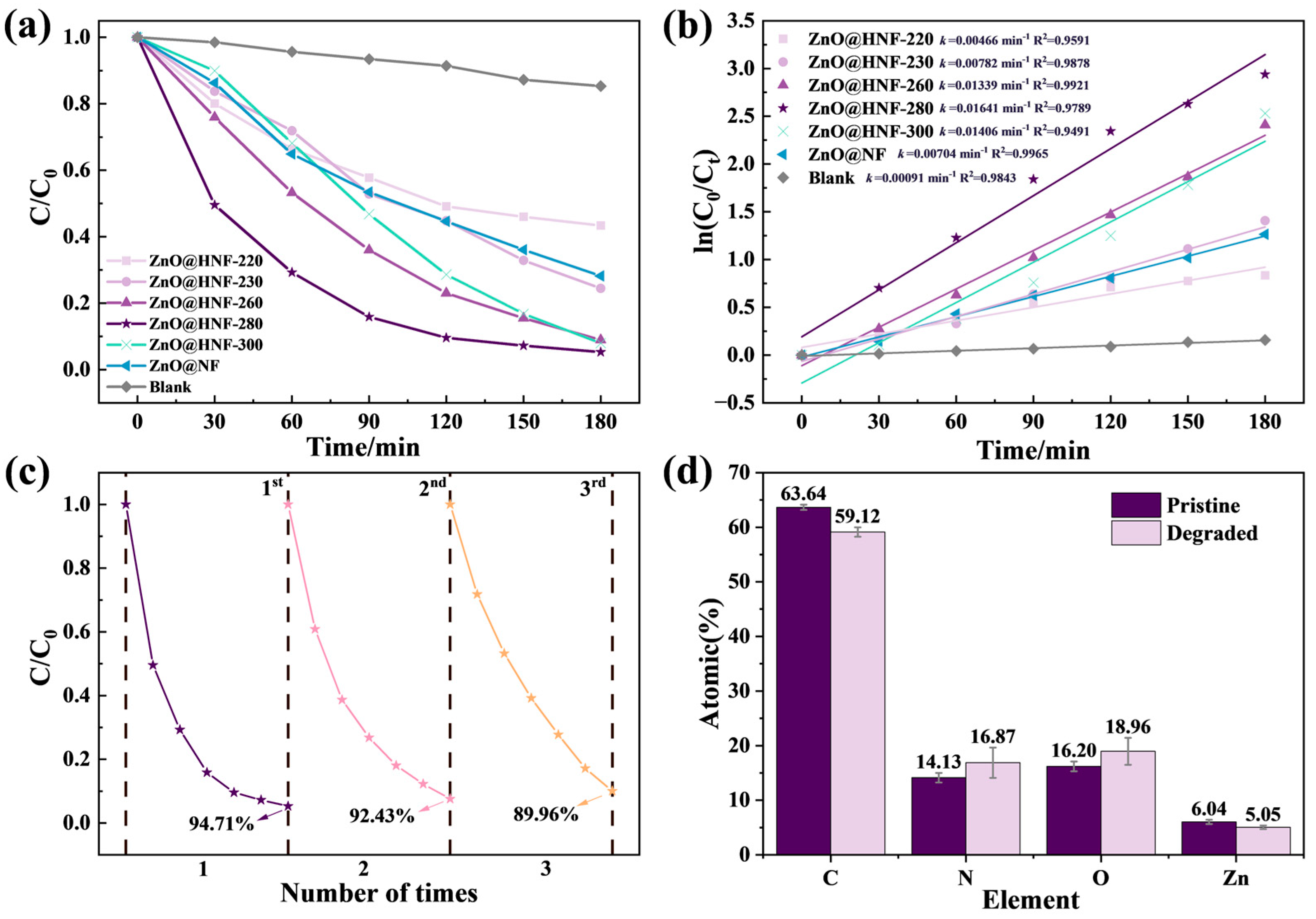

2.3. Photocatalytic Degradation Performance

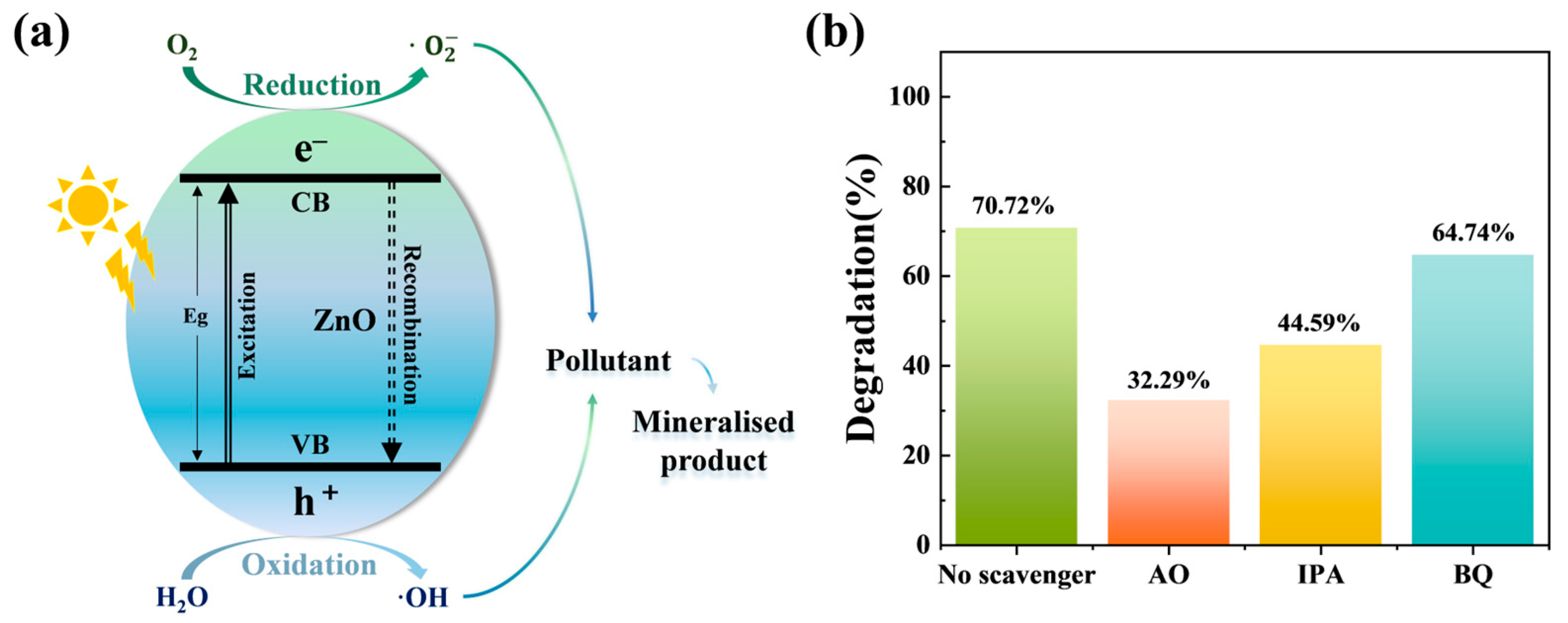

2.4. Photocatalytic Degradation Mechanism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

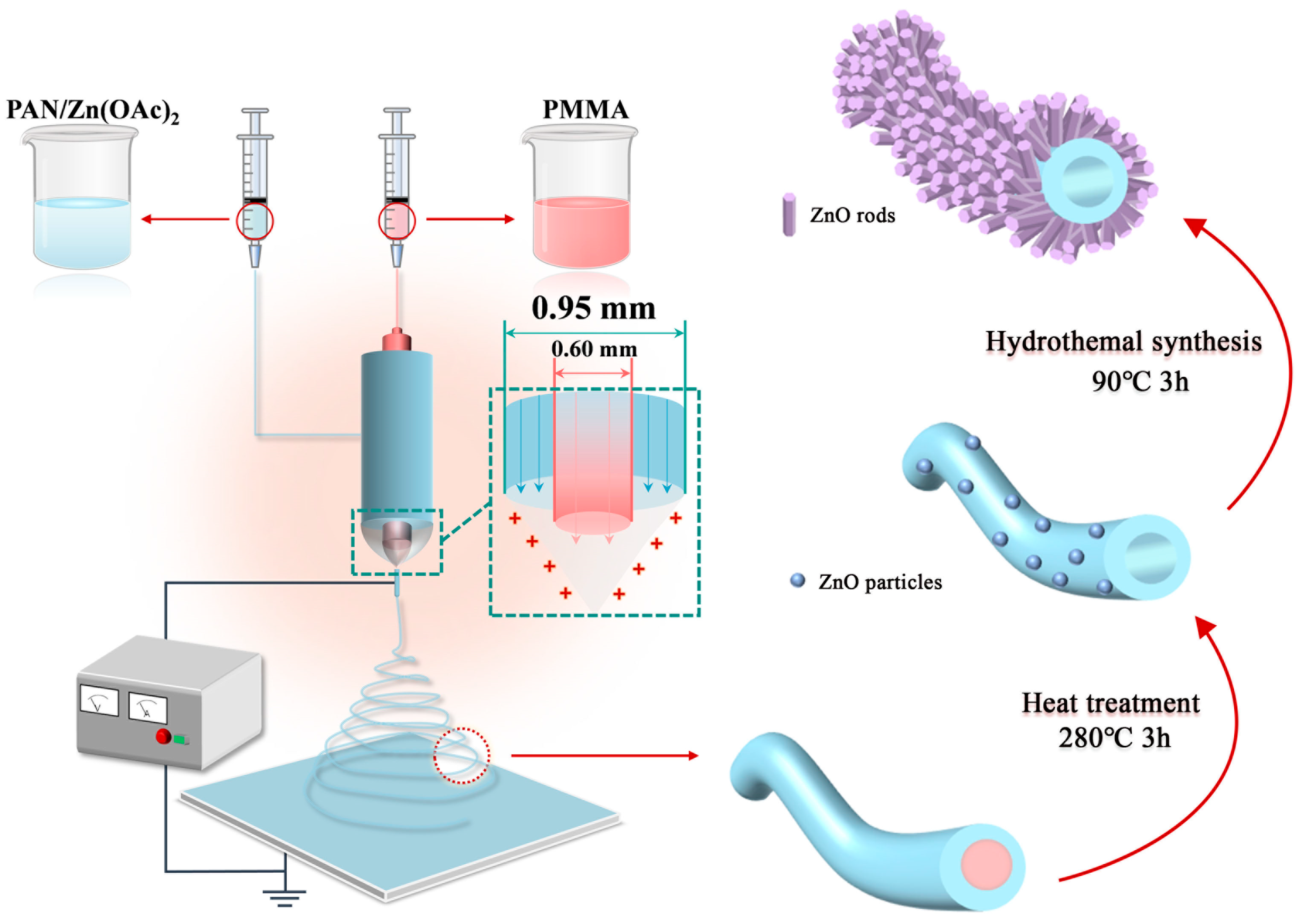

3.2. Preparation of ZnO@HNF

3.3. Measurement and Characterization

3.4. Photocatalytic Degradation Tests

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raza, A.; Altaf, S.; Ali, S.; Ikram, M.; Li, G. Recent advances in carbonaceous sustainable nanomaterials for wastewater treatments. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2022, 32, e00406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubchenco, J. Entering the century of the environment: A New Social Contract for Science. Science 1998, 279, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakruthi, K.; Ujwal, M.P.; Yashas, S.R.; Mahesh, B.; Kumara Swamy, N.; Shivaraju, H.P. Recent advances in photocatalytic remediation of emerging organic pollutants using semiconducting metal oxides: An overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 4930–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moztahida, M.; Lee, D.S. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue with P25/Graphene/Polyacrylamide hydrogels: Optimization using response surface methodology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 400, 123314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Gong, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, S.; Ye, J.; Wang, Z.; Dionysiou, D.D. Dissolved organic matter promotes photocatalytic degradation of refractory organic pollutants in water by forming hydrogen bonding with photocatalyst. Water Res. 2023, 242, 120297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantò, F.; Dahrouch, Z.; Saha, A.; Patanè, S.; Santangelo, S.; Triolo, C. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye by porous zinc oxide nanofibers prepared via electrospinning: When defects become merits. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 557, 149830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zeng, G.; Tang, L.; Fan, C.; Zhang, C.; He, X.; He, Y. An overview on limitations of Tio2-based particles for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants and the corresponding countermeasures. Water Res. 2015, 79, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Noor, A.E.; Anwar, A.; Majeed, S.; Khan, S.; Ul Nisa, Z.; Ali, S.; Gnanasekaran, L.; Rajendran, S.; Li, H. Support based metal incorporated layered nanomaterials for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. Environ. Res. 2024, 260, 119481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusain, R.; Gupta, K.; Joshi, P.; Khatri, O.P. Adsorptive removal and photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants using metal oxides and their composites: A comprehensive review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 272, 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Rashid, M.; Haider, A.; Naz, S.; Haider, J.; Raza, A.; Ansar, M.T.; Uddin, M.K.; Ali, N.M.; Ahmed, S.S.; et al. A review of photocatalytic characterization, and environmental cleaning, of metal oxide nanostructured materials. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2021, 30, e00343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Liang, Q.; Yan, M.; Liu, Z.; He, Q.; Wu, T.; Luo, S.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Y. Advances in preparation, mechanism and applications of graphene quantum dots/semiconductor composite photocatalysts: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegel, J.; Povey, I.M.; Pemble, M.E. Zinc oxide for solar water splitting: A brief review of the material’s challenges and associated opportunities. Nano Energy 2018, 54, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasso Guaraldo, T.; Wenk, J.; Mattia, D. Photocatalytic ZnO foams for micropollutant degradation. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2021, 5, 2000208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Lv, M.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, X.; Lou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Cheng, H.; Dai, Y.; et al. Single-particle imaging photoinduced charge transfer of ferroelectric polarized heterostructures for photocatalysis. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 25522–25534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negash, A.; Mohammed, S.; Weldekirstos, H.D.; Ambaye, A.D.; Gashu, M. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye using eco-friendly synthesized rGO@ZnO nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Segura, S.; Ocon, J.D.; Chong, M.N. Electrochemical oxidation remediation of real wastewater effluents—A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 113, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kaushik, R.D.; Purohit, L.P. ZnO-CdO nanocomposites incorporated with graphene oxide nanosheets for efficient photocatalytic degradation of bisphenol a, thymol blue and ciprofloxacin. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.S.; Strunk, J.; Chong, M.N.; Poh, P.E.; Ocon, J.D. Multi-dimensional zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoarchitectures as efficient photocatalysts: What is the fundamental factor that determines photoactivity in ZnO? J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 381, 120958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Hou, H.; Liu, Z.; Gao, F.; Zheng, J.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Ying, P.; Yang, W.; Wu, T. Shape-enhanced photocatalytic activities of thoroughly mesoporous ZnO nanofibers. Small 2016, 12, 4007–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, H.K.; Vij, M.; Maurya, K.K. Synthesis, characterization and sun light-driven photocatalytic activity of zinc oxide nanostructures. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2020, 20, 3683–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, W.A.A.; Handal, H.T.; Ibrahem, I.A.; Galal, H.R.; Mousa, H.A.; Labib, A.A. Recycling for solar photocatalytic activity of dianix blue dye and real industrial wastewater treatment process by zinc oxide quantum dots synthesized by solvothermal method. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 404, 123962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Mei, W.; Wang, C.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, T. Synthesis of a flower-like SnO/ZnO nanostructure with high catalytic activity and stability under natural sunlight. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 826, 154122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, C.; Chen, H.; Han, X.; Zhang, W.; Wu, J.; Liang, F.; Dai, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, K.-Q.; et al. Rational construction of ZnO/CuS heterostructures-modified pvdf nanofiber photocatalysts with enhanced photocatalytic activity. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 34107–34116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Kang, T.; Du, F.; Han, P.; Gao, M.; Hu, P.; Teng, F.; Fan, H. A new S-scheme heterojunction of 1D ZnGa2O4/ZnO nanofiber for efficient photocatalytic degradation of TC-HCl. Environ. Res. 2023, 232, 116388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Wei, L.; Liu, Y.; Shao, C. ZnO hollow nanofibers: Fabrication from facile single capillary electrospinning and applications in gas sensors. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 19397–19403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaci, F.; Vempati, S.; Ozgit-Akgun, C.; Donmez, I.; Biyikli, N.; Uyar, T. Transformation of polymer-ZnO core–shell nanofibers into ZnO hollow nanofibers: Intrinsic defect reorganization in ZnO and its influence on the photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 176–177, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, T.S.E.; de Paulo Ferreira, E.; Vieira, P.A.; Reis, M.H.M. Decoration of alumina hollow fibers with zinc oxide: Improvement of the photocatalytic system for methylene blue degradation. Environ. Sci Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 66741–66756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Garcia, W.; Ramakrishna, S.; Thomas, S.W. Electrospinning technique for fabrication of coaxial nanofibers of semiconductive polymers. Polymers 2022, 14, 5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Yang, W.; Yi, W.; Sun, Y.; Yu, N.; Wang, J. Oxygen-plasma-assisted enhanced acetone-sensing properties of ZnO nanofibers by electrospinning. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 23084–23093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, A.; Samadi, M.; Pourjavadi, A.; Ramakrishna, S.; Moshfegh, A.Z. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of ZnO/g-C3N4 nanofibers constituting carbonaceous species under simulated sunlight for organic dye removal. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 26185–26196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Li, Z.; Li, K.; Zhang, L.; Meng, A. SiO2/ZnO composite hollow sub-micron fibers: Fabrication from facile single capillary electrospinning and their photoluminescence properties. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, W.; Han, P.; Yang, J.; Wan, Z.; Hu, P.; Teng, F.; Fan, H. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride by hollow nanofiber ag@ZnGa2O4/ZnO with synergistic effects of LSPR and S-Scheme interface engineering. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 17448–17457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Dong, W.; Liu, Y. High photocatalytic activity material based on high-porosity ZnO/CeO2 nanofibers. Mater. Lett. 2012, 80, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, H.; Li, S.; Li, J. Electrospun hollow ZnO/NiO heterostructures with enhanced photocatalytic activity. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 67610–67616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, P.; Das, D. Photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine-B dye by stable ZnO nanostructures with different calcination temperature induced defects. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 465, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, C.; Cao, W. Effect of polyacrylonitrile precursor orientation on the structures and properties of thermally stabilized carbon fiber. Materials 2021, 14, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullayeva, N.; Tuc Altaf, C.; Kumtepe, A.; Yilmaz, N.; Coskun, O.; Sankir, M.; Kurt, H.; Celebi, C.; Yanilmaz, A.; Demirci Sankir, N. Zinc oxide and metal halide perovskite nanostructures having tunable morphologies grown by nanosecond laser ablation for light-emitting devices. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 5881–5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejsmont, A.; Goscianska, J. Hydrothermal synthesis of ZnO superstructures with controlled morphology via temperature and pH optimization. Materials 2023, 16, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauc, J.; Grigorovici, R.; Vancu, A. Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous germanium. Phys. Status Solidi 1966, 15, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, J.B.; Birnie, D.P., III. Assessing tauc plot slope quantification: ZnO thin films as a model system. Phys. Status Solidi 2018, 255, 1700393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurylev, V.; Perng, T.P. Defect engineering of ZnO: Review on oxygen and zinc vacancies. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 4977–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Nan, D.; Wang, B.; He, L.; Zhang, J.; Tang, X.; Duan, H.; Liu, Y. Effect of oxygen vacancy defect regeneration on photocatalytic properties of Zno nanorods. Appl. Phys. A 2020, 126, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, D.; Hu, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, L.; Yang, M.; Feng, Q. Electrospun flexible core-sheath PAN/PU/β-CD@ag nanofiber membrane decorated with ZnO: Enhance the practical ability of semiconductor photocatalyst. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 39638–39648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, H.M.; Sayed, M.M.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; El-sadek, M.S.A.; Nasr, E.A.; Mohamed, M.A.; Taha, M. Engineering of multifunc-tional nanocomposite membranes for wastewater treatment: Oil/water separation and dye degradation. Membranes 2023, 13, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjith, K.S.; Yildiz, Z.I.; Khalily, M.A.; Huh, Y.S.; Han, Y.-K.; Uyar, T. Membrane-based electrospun poly-cyclodextrin nano-fibers coated with ZnO nanograins by ALD: Ultrafiltration blended photocatalysis for degradation of organic micropollutants. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 686, 122002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, S.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, K.; Duan, G.; Yang, W.; Jiang, S. Hydrothermal synthesis of Ce-doped ZnO heterojunction sup-ported on carbon nanofibers with high visible light photocatalytic activity. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2021, 37, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xu, L.; Ahmed, A. Carbon quantum dots-decorated Zno heterostructure nanoflowers grown on nanofiber membranes as high-efficiency photocatalysts. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 136, 109972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zussman, E.; Yarin, A.L.; Bazilevsky, A.V.; Avrahami, R.; Feldman, M. Electrospun polyaniline/poly(methyl methacrylate)-derived turbostratic carbon micro-/nanotubes. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, N.H.; Jaafar, J.; Samitsu, S.; Ismail, A.F.; Mohamed, M.A.; Othman, M.H.D.; Rahman, M.A.; Othman, N.H.; Nor, N.A.M.; Yusof, N.; et al. Mechanistic insight of the formation of visible-light responsive nanosheet graphitic carbon nitride embedded polyacrylonitrile nanofibres for wastewater treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 33, 101015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time (min) | 0 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 | 180 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| η under UV (%) | ZnO@HNF-220 | 0 | 19.92 | 33.63 | 42.22 | 50.85 | 53.98 | 56.64 |

| ZnO@HNF-230 | 0 | 16.22 | 28.10 | 47.12 | 55.19 | 67.11 | 75.51 | |

| ZnO@HNF-260 | 0 | 24.04 | 46.74 | 63.97 | 76.96 | 84.50 | 91.01 | |

| ZnO@HNF-280 | 0 | 50.44 | 70.72 | 84.12 | 90.40 | 92.77 | 94.70 | |

| ZnO@HNF-300 | 0 | 10.08 | 31.84 | 53.21 | 71.36 | 83.18 | 92.03 | |

| ZnO@NF | 0 | 13.68 | 35.08 | 46.54 | 55.35 | 63.89 | 71.78 | |

| Blank | 0 | 1.50 | 4.34 | 6.55 | 8.57 | 12.78 | 14.67 | |

| η under sunlight (%) | ZnO@HNF-280 | 0 | 56.81 | 75.68 | 85.98 | 89.62 | 91.49 | 92.95 |

| Catalysts | Catalyst Dosage (mg) | MB Solution (mL, mg/L) | Time (min) | Degradation Efficiency (%) | k (min−1) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO NPs | 20 | 100, 15 | 120 | 96.5, 81 after 10 cycles | 0.00497 | [15] |

| rGO@ZnO-NCs | 99, 84 after 10 cycles | 0.00503 | ||||

| PVDF/ZnO/CuS | / | 50, 20 | 420 | 93.3, >90 after 4 cycles | 0.00901 | [23] |

| ZnO/carbon/g-C3N4 | 10 | 10, 3.2 | 120 | 91.8, no cycle | 0.0206 | [30] |

| PPCD@3Ag/ZnO | 50 | 50, 10 | 120 | 71.5, 64.2 after 5 cycles | 0.0115 | [43] |

| CA/ZnO@TiO2 | 10 | 15, 10 | 120 | 80, no cycle | 0.00175 | [44] |

| ZnO@poly-CD | / | 10, 15 | 120 | 94.3, 93.6 after 10 cycles | / | [45] |

| Ce/ZnO/CNFs | 60 | 50, 10 | 420 | 96, decreased slightly after 3 cycles | 0.00540 | [46] |

| ZnO@HNF-280 | 30 | 30, 10 | 180 | 94.70, 89.96 after 5 cycles | 0.01641 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, Y.; Xu, L. Hollow ZnO Nanofibers for Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1137. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121137

Cao Y, Xu L. Hollow ZnO Nanofibers for Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1137. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121137

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Yilin, and Lan Xu. 2025. "Hollow ZnO Nanofibers for Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1137. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121137

APA StyleCao, Y., & Xu, L. (2025). Hollow ZnO Nanofibers for Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Catalysts, 15(12), 1137. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121137