Greener Catalytic Oxidation of Azole Fungicides: Coupling EO–O3 on BDD with Kinetics and Mineralization Targets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Pollutants Abatement

2.1.1. ANOVA Test Interpretation

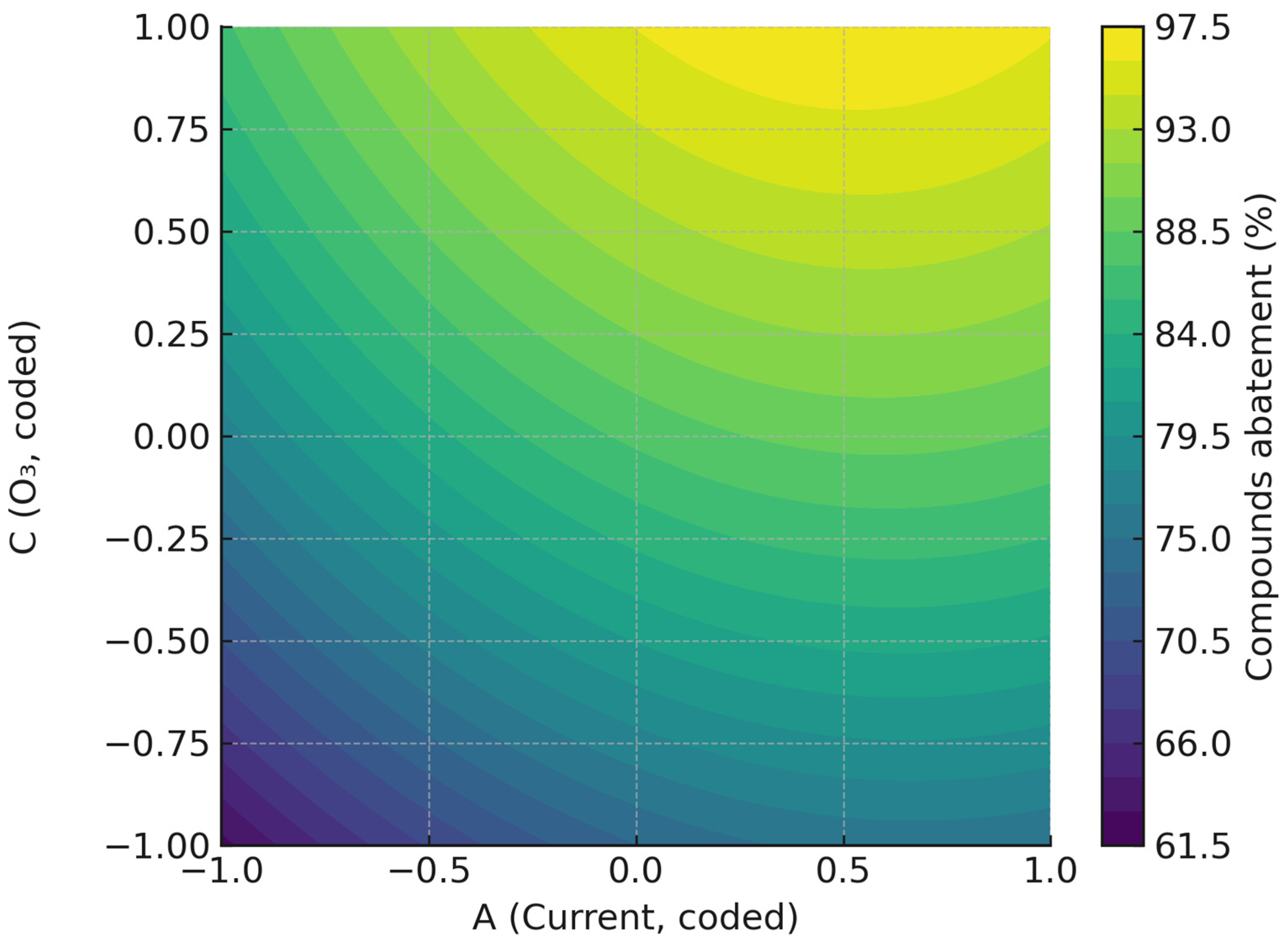

2.1.2. Influence of Operating Variables and Optimization

2.2. Kinetics as Target Variable

2.2.1. ANOVA Test Interpretation

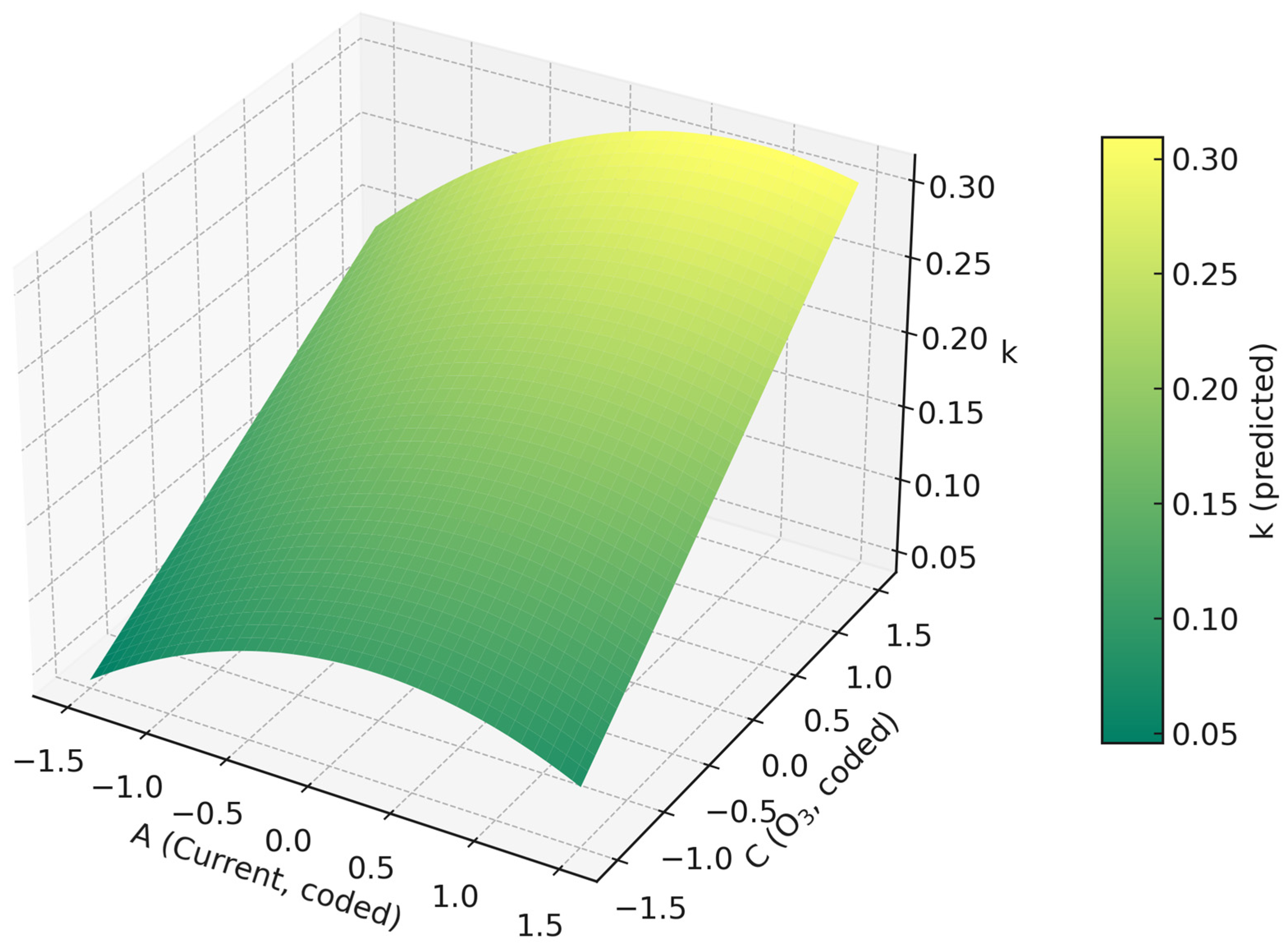

2.2.2. Influence of Operating Variables and Optimization

2.3. Mineralization as Target Variable

2.3.1. ANOVA Test

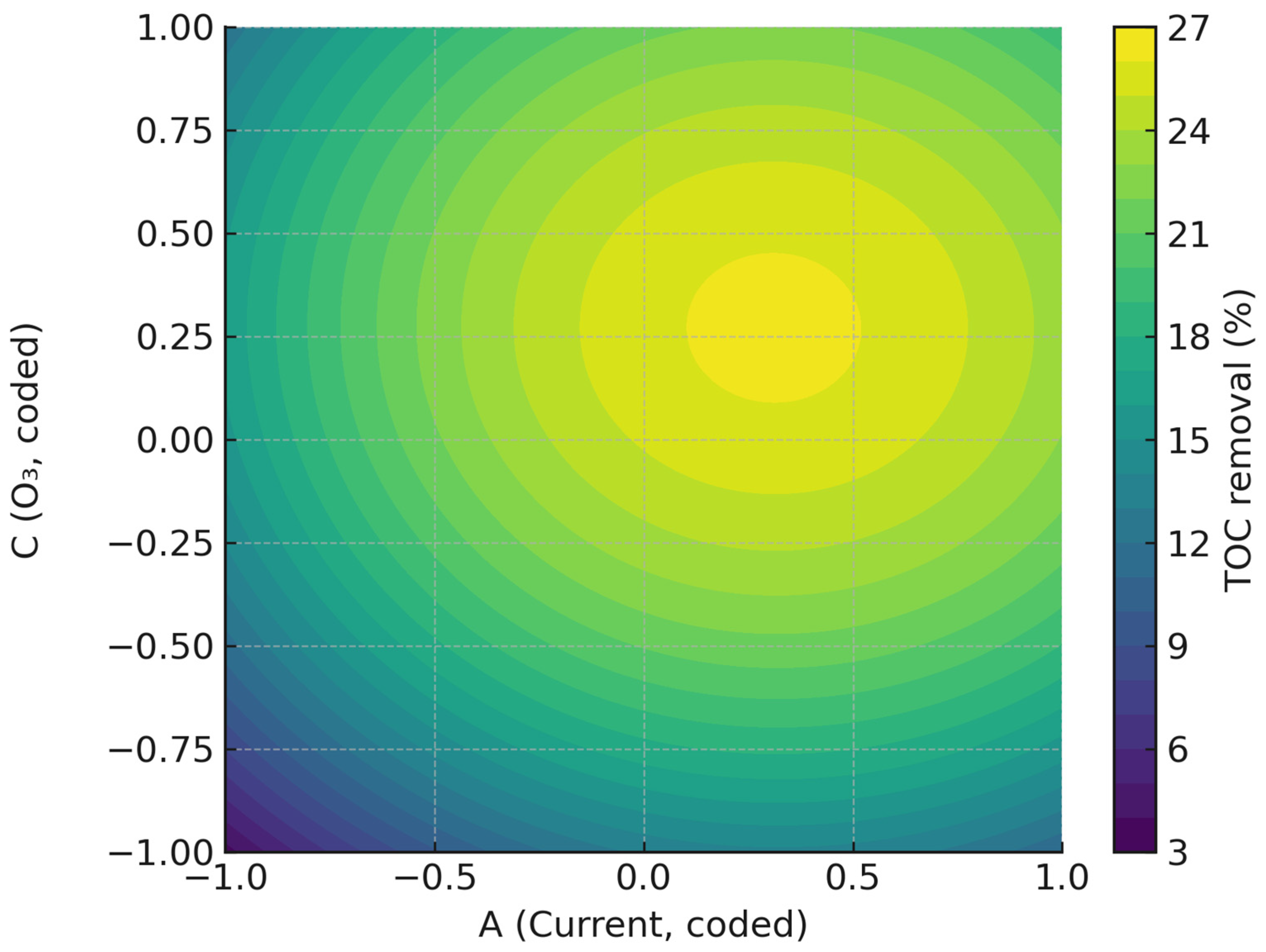

2.3.2. Influence of Operating Variables and Optimization

2.4. Energy Considerations

2.5. Practical Implications and Scale-Up

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Oxidation Systems

3.2.1. Ozonation (O3)

3.2.2. Electro-Oxidation (EO)

3.3. Operating Conditions

3.4. Analytical Note

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, J.; Xia, W.; Wan, Y.; Xu, S. Azole and strobilurin fungicides in source, treated, and tap water from wuhan, Central China: Assessment of human exposure potential. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.; Lee, H.; Bae, H.; Jeon, J. Comparative insight of pesticide transformations between river and wetland systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 879, 163172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, P.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Carlucci, L.; Jeremiasse, A.W.; Rijnaarts, H.H.; Bruning, H. Effect of electrolyte composition on electrochemical oxidation: Active sulfate formation, benzotriazole degradation, and chlorinated by-products distribution. Environ. Res. 2022, 211, 113057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoigné, J.; Bader, H. Rate constants of reactions of ozone with organic and inorganic compounds in water—I: Non-dissociating organic compounds. Water Res. 1983, 17, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrity, D.; Wert, E.C. The Role of Ozonation as an Advanced Oxidation Process for Attenuation of 1, 4-Dioxane in Potable Reuse Applications. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.H.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Liu, Y.; Zou, L.H. Recent Progress in Catalytically Driven Advanced Oxidation Processes for Wastewater Treatment. Catalysts 2025, 15, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.M.; Garrido, I.; Flores, P.; Hellín, P.; Contreras, F.; Fenoll, J. Ozonation for remediation of pesticide-contaminated soils at field scale. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponio, G.; Vendemia, M.; Mallardi, D.; Marsico, A.D.; Alba, V.; Gentilesco, G.; Forte, G.; Velasco, R.; Coletta, A. Pesticide Residues and Microbiome after Ozonated-Water Washing of Table Grapes. Foods 2023, 12, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, P.; Kiola, A. Micro and nanobubbles enhanced ozonation technology: A synergistic approach for pesticides removal. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, 70133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, C.; Wang, D.; Li, L.; Shao, L.; Hu, J. Research Progress of Micro-Nano Bubbles in Environmental Remediation: Mechanisms, preparation methods, and applications. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völker, J.; Stapf, M.; Miehe, U.; Wagner, M. Systematic review of toxicity removal by advanced wastewater treatment technologies via ozonation and activated carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7215–7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jin, R.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, J.; He, Z.; Jia, M.; Jiang, Y. Influencing Factors, Kinetics, and Pathways of Pesticide Degradation by Chlorine Dioxide and Ozone: A Comparative Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Escudero, C.M.; Garrido, I.; Ros, C.; Flores, P.; Hellín, P.; Contreras, F.; Fenoll, J. Remediation of pesticides in commercial farm soils by solarization and ozonation techniques. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 329, 117062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerrity, D.; Gamage, S.; Holady, J.C.; Mawhinney, D.B.; Quiñones, O.; Trenholm, R.A.; Snyder, S.A. Pilot-scale evaluation of ozone and biological activated carbon for trace organic contaminant mitigation and disinfection. Water Res. 2011, 45, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E. Recent development of electrochemical advanced oxidation of herbicides. A review on its application to wastewater treatment and soil remediation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosler, P.; Girão, A.V.; Silva, R.F.; Tedim, J.; Oliveira, F.J. Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Using BDD—A Review. Environments 2023, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Song, G.; Sun, J.; Zhou, M. Electrochemical Advanced oxidation processes towards carbon neutral wastewater treatment: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 480, 148044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Chen, L. A review on electrochemical advanced oxidation treatment of dairy wastewater. Environments 2024, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjenovic, J.; Sedlak, D.L. Challenges and opportunities for electrochemical processes as next-generation technologies for the treatment of contaminated water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 11292–11302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Brillas, E. Decontamination of wastewaters containing synthetic organic dyes by electrochemical methods: A general review. Appl. Catal. B 2009, 87, 105–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wei, L.; Ru, Y.; Weng, M.; Wang, L.; Dai, Q. A mini-review of the electro-peroxone technology for wastewaters: Characteristics, mechanism and prospect. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, G.; Deng, S.; Huang, J.; Wang, B. The electro-peroxone process for the abatement of emerging contaminants: Mechanisms, recent advances, and prospects. Chemosphere 2018, 208, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Li, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bao, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Leung, K.M.Y. UV-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes for Antibiotic Resistance Control: Efficiency, Influencing Factors, and Energy Consumption. Engineering 2024, 37, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oturan, M.A.; Aaron, J.J. Advanced oxidation processes in water/wastewater treatment: Principles and applications. A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 44, 2577–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, U.; Spahr, S.; Lutze, H.; Wieland, A.; Rüting, S.; Gernjak, W.; Wenk, J. Advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment–Guidance for systematic future research. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 9th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, R.H.; Montgomery, D.C.; Anderson-Cook, C.M. Response Surface Methodology: Process and Product Optimization Using Designed Experiments, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.P.; Draper, N.R. Response Surfaces, Mixtures, and Ridge Analyses, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C. Experimental Design for Product and Process Design; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrkhah, R.; Hadavifar, M.; Mehrkhah, M.; Baghayeri, M.; Lee, B.H. Recent advances in titanium-based boron-doped diamond electrodes for enhanced electrochemical oxidation in industrial wastewater treatment: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 358, 130218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.Y.; Xiang, F.Y.; Mao, J.Q.; Ding, Y.L.; Tong, S.P. Oxidative efficiency of ozonation coupled with electrolysis for treatment of acid wastewater. J. Electrochem. 2022, 28, 2104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Yuan, S.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Bakheet, B.; Komarneni, S.; Wang, Y. Investigation of the synergistic effects for p-nitrophenol mineralization by a combined process of ozonation and electrolysis using a boron-doped diamond anode. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 280, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado-Piña, D.; Roa-Morales, G.; Barrera-Díaz, C.; Balderas-Hernandez, P.; Romero, R.; Martín del Campo, E.; Natividad, R. Synergic Effect of Ozonation and Electrochemical Methods on Oxidation and Toxicity Reduction: Phenol Degradation. Fuel 2017, 198, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J.R.; González, T.; Montero-Fernández, I. Degradation of Azole Pesticides in WWTP Effluent by Hybrid Advanced Oxidation Processes: UV, O3, US, EO, US/UV, O3/EO, O3/US, UV/O3, UV/EO, UV/O3/US, and UV/O3/EO. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Ren, X.; Zhou, M. A Critical Review of Ozone-Based Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water Treatment: Fundamentals, Stability Evaluation, and Application. Chemosphere 2024, 365, 143330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Chen, Z.; Du, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Crittenden, J.C.; Wang, X. Development of an electrochemical oxidation processes model: Revelation of process mechanisms and impact of operational parameters on process performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 158574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Peña, M.; Barrios Pérez, J.A.; Llanos, J.; Sáez, C.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Barrera-Díaz, C.E. New insights about the electrochemical production of ozone. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2021, 27, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Sonntag, C.; Von Gunten, U. Reaction of Ozone with Hydrogen Peroxide (Peroxone Process): A Revision of Current Mechanistic Concepts Based on Thermokinetic and Quantum-Chemical Considerations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3505–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, I.M.G.; Fernández Mena, I.; Moratalla Tolosa, A.; Sáez Jiménez, C.; Pinheiro de Souza, L.; Teixeira, A.C.S.C.; Rodrigo, M.A. Intensification of peroxone production through the paired generation of hydrogen peroxide and ozone in a continuous flow electrochemical reactor. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 524, 146049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, B.; Dagnew, M.; Yu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, C. Synergistic mechanisms of 3D electrochemical processes and multi-oxidant integration for enhanced water purification. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 75, 107882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Run Nº | Current (A) | Electrolyte Concentration (B) | Ozone Concentration (C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | −1.68179 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1.68179 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | −1 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | −1.68179 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | −1.68179 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | −1 | −1 | 1 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 1.68179 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 1 | −1 | 1 |

| 14 | 0 | 1.68179 | 0 |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | 1 | −1 | −1 |

| 17 | −1 | 1 | 1 |

| 18 | −1 | 1 | −1 |

| 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 2575 | 9 | 286.1 | 6.570 | 0.0035 |

| Error | 435.5 | 10 | 43.55 | ||

| Total | 3011 | 19 |

| Term | Coef | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 87.3580 | 2.6918 | 32.4539 | 0.0000 |

| A | 5.5234 | 1.7859 | 3.0927 | 0.0114 |

| B | 0.6957 | 1.7859 | 0.3896 | 0.7050 |

| C | 11.3093 | 1.7859 | 6.3325 | 0.0001 |

| AB | −1.4563 | 2.3334 | −0.6241 | 0.5465 |

| AC | −0.7588 | 2.3334 | −0.3252 | 0.7518 |

| BC | −0.0788 | 2.3334 | −0.0337 | 0.9737 |

| A2 | −4.6469 | 1.7385 | −2.6729 | 0.0234 |

| B2 | −0.1303 | 1.7385 | −0.0749 | 0.9417 |

| C2 | −2.6352 | 1.7385 | −1.5158 | 0.1605 |

| Term | Coef | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.1994 | 0.0148 | 13.4403 | 0.0000 |

| A | 0.0250 | 0.0098 | 2.5428 | 0.0292 |

| B | 0.0028 | 0.0098 | 0.2840 | 0.7822 |

| C | 0.0624 | 0.0098 | 6.3438 | 0.0001 |

| AB | −0.0067 | 0.0129 | −0.5210 | 0.6137 |

| AC | 0.0089 | 0.0129 | 0.6959 | 0.5023 |

| BC | 0.0043 | 0.0129 | 0.3324 | 0.7464 |

| A2 | −0.0214 | 0.0096 | −2.2346 | 0.0495 |

| B2 | 0.0045 | 0.0096 | 0.4700 | 0.6484 |

| C2 | 0.0004 | 0.0096 | 0.0402 | 0.9688 |

| Term | Coef | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 25.1129 | 2.8895 | 8.6912 | 0.0000 |

| A | 3.6614 | 1.9171 | 1.9099 | 0.0852 |

| B | −7.6605 | 1.9171 | −3.9959 | 0.0025 |

| C | 4.2213 | 1.9171 | 2.2019 | 0.0523 |

| AB | 0.4688 | 2.5048 | 0.1871 | 0.8553 |

| AC | −0.1088 | 2.5048 | −0.0434 | 0.9662 |

| BC | −2.7513 | 2.5048 | −1.0984 | 0.2978 |

| A2 | −5.8386 | 1.8662 | −3.1286 | 0.0107 |

| B2 | −2.5029 | 1.8662 | −1.3411 | 0.2095 |

| C2 | −7.7425 | 1.8662 | −4.1487 | 0.0020 |

| Metric | Formula (Word Equation) | Units | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EO power density | W·L−1 | 7.20 | |

| O3 power density | W·L−1 | 3.75 | |

| Total power density | W·L−1 | 10.95 | |

| Treatment time | s | 600 | |

| EO energy per liter | kWh·L−1 | 0.00120 | |

| O3 energy per liter | kWh·L−1 | 0.00062 | |

| Total energy per liter | kWh·L−1 | 0.00182 | |

| Specific energy consumption | kWh·m−3 | 1.825 | |

| Electrical energy per order | kWh·m−3·order−1 | 10.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dominguez, J.R.; González, T.; Simón-García, D. Greener Catalytic Oxidation of Azole Fungicides: Coupling EO–O3 on BDD with Kinetics and Mineralization Targets. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121136

Dominguez JR, González T, Simón-García D. Greener Catalytic Oxidation of Azole Fungicides: Coupling EO–O3 on BDD with Kinetics and Mineralization Targets. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121136

Chicago/Turabian StyleDominguez, Joaquin R., Teresa González, and David Simón-García. 2025. "Greener Catalytic Oxidation of Azole Fungicides: Coupling EO–O3 on BDD with Kinetics and Mineralization Targets" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121136

APA StyleDominguez, J. R., González, T., & Simón-García, D. (2025). Greener Catalytic Oxidation of Azole Fungicides: Coupling EO–O3 on BDD with Kinetics and Mineralization Targets. Catalysts, 15(12), 1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121136