Abstract

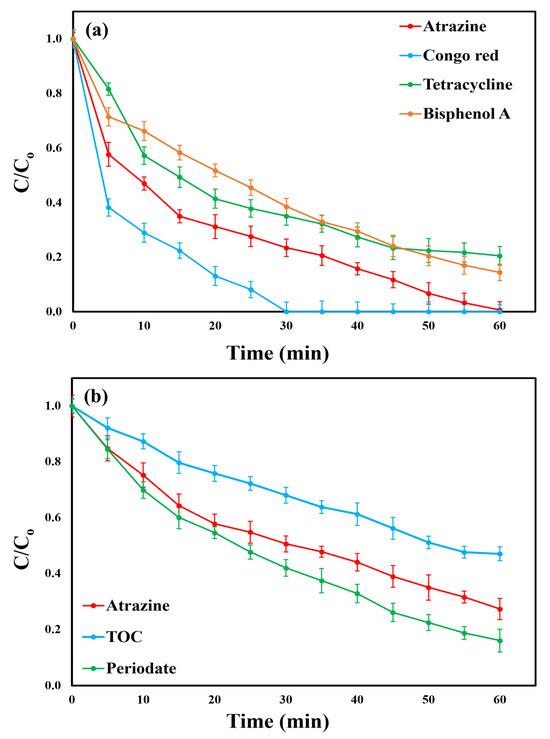

This study transformed discarded courgette biomass into biochar (BC) via pyrolysis at 500 °C and employed it as an activator of potassium periodate (PI) for atrazine (ATZ) degradation. Characterization analyses confirmed that the synthesized BC possessed a porous structure, a high carbon content (76.13%), crystalline SiO2, KCl, and CaCO3 phases, as well as abundant oxygen-containing functional groups (–OH, C=O, C=C, –COOH), which are favorable for catalytic activation. The point of zero charge of 4.25 indicates that the BC surface carries a suitable charge distribution, promoting effective electrostatic interactions under near-neutral pH conditions. Under optimal operating conditions (neutral pH, [ATZ]o = 7.3 mg/L, [PI]o = 2.7 mM, [BC]o = 0.55 g/L, and 25 ± 0.5 °C), the system achieved 99.35% ATZ removal (first-order kinetic rate constant = 0.0601 min−1) and 64.23% TOC mineralization within 60 min. Quenching tests confirmed iodate radicals and singlet oxygen as the primary species, with hydroxyl and superoxide radicals playing secondary roles. The proposed mechanism suggests that electron transfer from oxygen-containing groups on the BC surface activates PI, leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species that facilitate ATZ degradation via synergistic radical and non-radical pathways. The BC catalyst exhibited strong recyclability, with only ~9% efficiency loss after five cycles. The BC/PI system also demonstrated high removal of tetracycline (79.54%) and bisphenol A (85.6%) within 60 min and complete Congo red dye degradation in just 30 min. Application to real industrial wastewater achieved 72.77% ATZ removal, 53.02% mineralization, and a treatment cost of 1.2173 $/m3, demonstrating the practicality and scalability of the BC/PI system for sustainable advanced wastewater treatment.

1. Introduction

Atrazine (ATZ), a commonly used herbicide, presents major environmental and health concerns due to its long-lasting presence in aquatic systems and its risk of polluting water supplies [1]. As a common agricultural chemical, ATZ is often found in surface water and groundwater, where it can accumulate and affect both aquatic life and human health [2]. Environmental issues include its harmful effects on marine life and its impact on ecosystem balance. In humans, long-term exposure to atrazine has been connected to various health risks, such as hormonal imbalances, reproductive problems, and cancer [3,4]. Given these concerns, it is crucial to remove ATZ from wastewater before it is discharged into water bodies. Conventional treatment methods for ATZ removal, including biological, physical, and chemical processes, are often insufficient due to their limitations. Biological treatments, such as activated sludge processes, use microorganisms to degrade pollutants [5]. However, ATZ’s chemical stability and resistance to biodegradation make these methods ineffective, with ATZ potentially accumulating in the sludge [6]. Physical methods, such as adsorption, can capture ATZ but are hindered by the high material costs and the need for frequent regeneration. Membrane filtration, such as reverse osmosis, is also energy-intensive and generates large volumes of wastewater, making it impractical for large-scale applications [7]. Chemical treatments, such as chlorination, can degrade ATZ but are costly, require specialized equipment, and may produce harmful by-products [8]. These conventional methods often fail to offer an efficient and cost-effective solution for ATZ removal, underscoring the need for alternative, economical, and sustainable approaches [9].

Recently, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have emerged as impactful methods for removing refractory organic micropollutants from aqueous solutions [10]. These processes rely on generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) using oxidants, e.g., hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), peracetic acid, peroxymonosulfate (PMS), persulfate (PS), and periodate (PI, IO4−) [11,12,13]. Among these oxidants, PI exhibits superior oxidation capability owing to its longer and weaker I–O bond (≈1.78 Å), compared to the O–O bonds in PS (1.497 Å), PMS (1.453 Å), and H2O2 (1.457 Å; bond energy ≈ 213 kJ/mol) [12,14]. This structural feature facilitates easier bond cleavage and enhances the formation of highly reactive radicals such as iodate radicals (•IO3) and periodate radicals (•IO4). These radicals possess high redox potentials and longer lifetimes (up to 10−3 s) relative to hydroxyl radicals (•OH; lifetime ≈ 10−9 s) and sulfate radicals (lifetime ≈ 10−6 s), allowing for more sustained oxidation activity in aqueous systems [15]. These characteristics reduce spatial crowding around the central iodine atom, allowing PI to be safely stored and transported over extended periods without significant degradation or reactivity loss, making it easier for the molecule to interact with activators and generate ROS [16,17]. Gaber et al. [12] studied the degradation of tetracycline using a green-synthesized magnetite-supported biochar and reported a comparative evaluation of PI and other common oxidants. The PI-based system exhibited the highest oxidation performance among the tested oxidants, achieving a degradation efficiency of 83.4% with a corresponding pseudo-first-order rate constant of 0.0419 min−1. In contrast, the systems utilizing PS, PMS, and H2O2 achieved lower degradation efficiencies of 70.23, 61.19, and 39.27%, with respective rate constants of 0.0244, 0.019, and 0.0095 min−1. Elmitwalli et al. [18] compared the oxidation performance of different oxidants, including PI, PS, and H2O2, in the degradation of sulfamethazine using mulukhiyah stalks-derived biochar as a green activator. Among the tested systems, the PI-based system demonstrated the highest degradation efficiency, achieving nearly complete pollutant removal (below the detection limit) within 100 min, whereas the systems utilizing PS and H2O2 achieved lower degradation efficiencies of approximately 76 and 51%, respectively, under identical conditions.

Although PI can oxidize certain organic pollutants, its relatively slow reaction kinetics and moderate oxidation potential (+1.6 V vs. NHE) hinder its effectiveness in decomposing stable compounds. This limitation reduces its practicality in wastewater treatment applications, where rapid degradation is essential, and leads to higher operational costs [19]. To overcome these challenges, research has focused on activation techniques that enhance the reactivity of PI by generating highly oxidative ROS, including •IO3 radicals, superoxide radicals (O2•−), •OH radicals, and non-radical singlet oxygen (1O2). Several techniques have been developed to activate PI and enhance its oxidative capacity for pollutant degradation [20,21]. Common activation methods include ultraviolet light irradiation, transition metal catalysis, ultrasound, freezing, and the use of chemical activators like hydroxylamine and alkalis [18,22]. While these techniques improve the reactivity of periodate, they come with limitations. For instance, UV light activation can be energy-intensive and may require specialized equipment, while transition metal catalysis may result in metal ion leaching, leading to secondary contamination. Ultrasound and freezing methods also face challenges such as high operational costs and limited scalability [23,24]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to innovate environmentally friendly and economical activators for PI to enhance the degradation of persistent organic micropollutants.

Carbon-based materials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene oxide (GO) have been investigated as potential activators for PI because of their abundance of oxygen-rich functional groups and large surface area [14,19]. These characteristics enable the successful activation of oxidants such as PI and the production of ROS, promoting the effective breakdown of organic pollutants [25,26]. However, research on PI activation with carbonaceous compounds is limited, and the underlying mechanisms of the degradation process are not yet fully comprehended, warranting further investigation. Moreover, the practical application of these materials is often hindered by the complexity and high cost of their synthesis. The production of GO and CNTs, for instance, typically requires costly chemical precursors (such as graphite flakes or hydrocarbon gases), involves multiple oxidation and purification steps, and demands significant energy input during processing. These factors collectively result in elevated production costs and increased environmental footprints, restricting the large-scale feasibility of such materials [27,28]. Biochar presents several advantages over other carbonaceous materials when employed as a catalyst for PI activation. One of the primary benefits of biochar lies in its economic and environmental sustainability. Biochar is typically produced via the pyrolysis of abundant and low-cost biomass waste (e.g., agricultural residues, food waste, or forestry by-products), which not only provides a value-added route for waste utilization but also reduces overall production expenses [6,29]. Although the pyrolysis process consumes energy, its cost remains considerably lower than that associated with the synthesis of advanced carbon materials.

Furthermore, biochar exhibits a highly porous structure and abundant oxygen-containing surface functional groups that facilitate electron transfer to PI, generating ROS with strong oxidative potential. Its high adsorption capacity also enables the accumulation of organic pollutants near active sites, enhancing degradation efficiency. Therefore, biochar offers a practical, cost-effective, and sustainable alternative to engineered carbon materials for large-scale PI-based oxidation systems [30,31].

In this study, biochar derived from food waste in the form of discarded courgette biomass (including flesh, seeds, and peduncles) was synthesized through pyrolysis under a nitrogen atmosphere. The resulting courgette-derived BC was evaluated as a PI activator to degrade ATZ. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the application of the courgette-based biochar in water treatment that has not been previously fabricated in the literature. Due to its high moisture and organic matter content, improper management of courgette food waste not only results in leachate pollution but also leads to a significant loss of natural resources [32]. This study introduces a sustainable and low-cost PI activator that promotes resource recovery and supports circular waste management, while mitigating the environmental impacts of conventional food waste disposal. The synthesized BC was comprehensively characterized using advanced techniques to elucidate its structural, morphological, and surface chemical properties, thereby providing deeper insight into its potential catalytic activity. Preliminary control experiments were performed to clarify the specific role of the courgette-derived BC in activating PI and its synergistic effect on ATZ degradation. Additionally, the catalytic performance of BC toward PI activation was compared with other typical oxidants (PMS, PS, and H2O2) to determine the most efficient system for further investigations. In all experiments, the pseudo-first-order kinetic model was applied to determine the corresponding rate constants, which allowed a quantitative assessment of the ATZ catalytic efficiency. Further, the possible formation of toxic iodinated disinfection by-products (I-DBPs) during the degradation of ATZ in the BC/PI process was assessed. The effects of solution pH and temperature on ATZ degradation efficiency were individually investigated. In addition, key operational parameters, such as catalyst dosage, initial pollutant concentration, and PI concentration, were then optimized using response surface methodology (RSM) combined with a central composite design (CCD) to ensure a statistically robust evaluation of the system. On the other hand, the reusability of the catalyst was assessed over five successive cycles to evaluate its potential for long-term application in practical wastewater treatment processes. Quenching experiments were performed to identify the predominant ROS responsible for ATZ degradation in the BC/PI system, and the corresponding degradation mechanism was subsequently proposed. Furthermore, the efficiency of the BC/PI system was evaluated in different water matrices, and the influence of common coexisting constituents, such as natural organic matter (NOM) and various inorganic ions, was investigated to assess its performance under real environmental conditions. Moreover, the degradation pathways of ATZ were elucidated through the identification of its generated intermediates. In addition, the toxicity of ATZ and its degradation products was assessed to assess potential environmental risks. The universality of the system’s catalytic performance was further examined using representative model organic micropollutants. Finally, the scalability and practical feasibility of the BC/PI system were assessed using real agrochemical industrial wastewater containing ATZ, and the overall treatment cost was estimated to evaluate its economic viability for large-scale implementation.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of the Synthesized Biochar

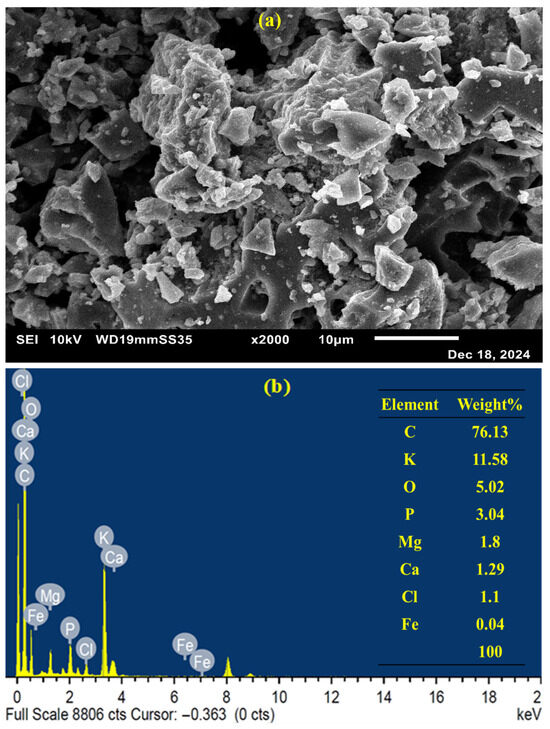

Figure 1a presents the SEM micrograph of the synthesized catalyst. The surface structure of the BC appears rough and irregular, which is likely linked to its high carbon content [6]. Additionally, the observed porous structure of the prepared BC is presumably a result of gas evolution during high-temperature pyrolysis [19]. The EDS pattern of the produced BC is shown in Figure 1b. The results revealed that carbon (C) and potassium (K) were the predominant elements in the prepared BC, with mass fractions of 76.13 and 11.58%, respectively. In addition, minor quantities of oxygen (O), phosphorus (P), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), chlorine (Cl), and iron (Fe) were detected, with respective mass fractions of 5.02, 3.04, 1.8, 1.29, 1.1, and 0.04%. These findings confirm that the synthesized BC is a carbon-rich material.

Figure 1.

(a) SEM image and (b) EDS pattern of the synthesized BC before treatment.

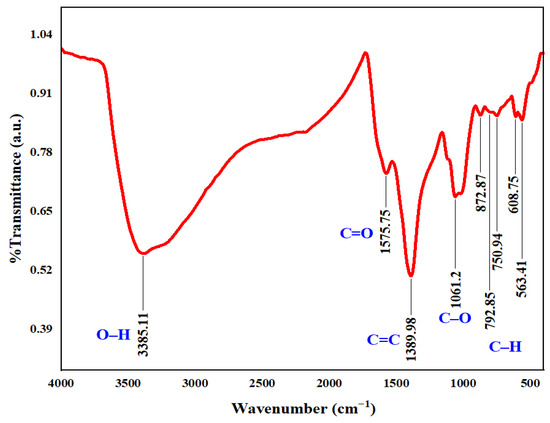

The broad FTIR survey of the catalyst before treatment is presented in Figure 2. The infrared peak at 3385.11 cm−1 was linked to the vibrations of the hydroxyl functional group (O–H) [16,19]. The characteristic bands observed at 1575.75 and 1389.98 cm−1 were assigned to the carbonyl group (C=O) and C=C group, respectively [16,33]. The absorption peak located at 1061.2 cm−1 corresponded to the carbon-oxygen bond of the carboxyl group (–COOH) [6,18]. The 563.4–872.87 cm−1 spectral range was matched with the C–H bond with different vibration modes [18,33]. These findings suggest that the catalyst is abundant in oxygen-containing functional groups. These functional groups likely enhance the synthesized BC’s ability to act as an activator for electron-transfer mediators and facilitate the decomposition of periodate [25]. A concise summary of the FTIR bands for the synthesized BC, along with a comparison to previously reported FTIR data from the literature and their associated functional groups, is provided in Table S1.

Figure 2.

FTIR full spectrum of the raw courgette-derive biochar.

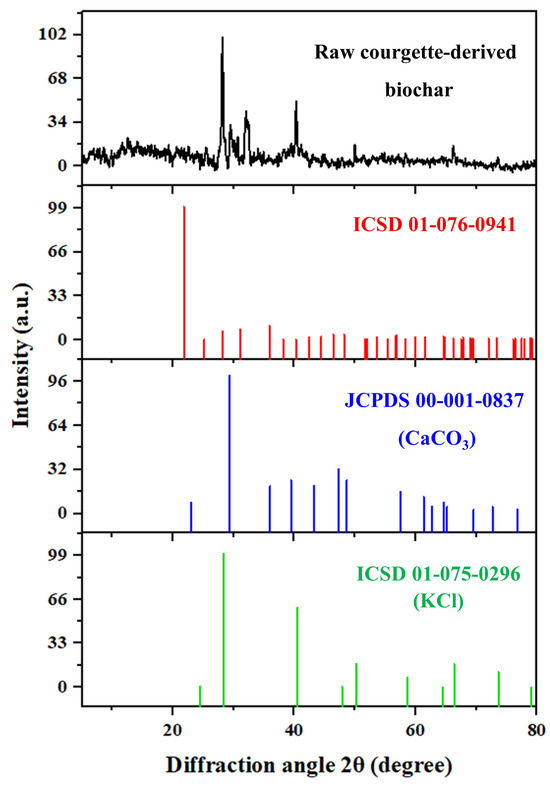

The XRD diffraction peaks of the synthesized BC correspond well with those of quartz (SiO2), potassium chloride (KCl), and calcite (CaCO3), as identified from their respective reference cards: ICSD No. 01-076-0941, ICSD No. 01-075-0296, and JCPDS No. 00-001-0837 (Figure 3). The complete list of diffraction peaks for the synthesized BC, along with the standard diffraction peaks and associated Miller indices (hkl) for SiO2, KCl, and CaCO3, is provided in Table S2. The diffraction peaks observed at 2θ° = 21.9°, 25.02°, 31.98°, 35.96°, 46.42°, 53.48°, and 58.64° were ascribed to the (101), (110), (102), (200), (113), (203), and (310) planes of SiO2, respectively. On the other hand, the diffraction peaks at 2θ° = 24.46°, 28.18°,40.88°, 50°, 66.24°, and 73.58° were well matched with the (111), (200), (220), (222), (420), and (422) planes of KCl, respectively. Further, the peaks located at 2θ° = 23.04°, 29.52°, 43.28°, 57.62°, and 62.62° were attributed to (012), (104), (202), (122), and (125) crystallographic planes of CaCO3, respectively. The characteristic peaks of carbon were absent due to carbon’s amorphous nature and overlapping with other diffraction peaks [33]. Gaber et al. [33] attributed the diffraction peaks of spinach-stalk biochar to SiO2, KCl, and CaCO3. Elmitwalli et al. [18] identified similar peaks in biochars from mulukhiyah stalks and potato peels. The presence of these crystalline mineral phases can be explained by the natural composition of the courgette biomass. Silicon dioxide arises from phytoliths, which are amorphous silica bodies accumulated in plant tissues during growth and commonly retained in biochar after pyrolysis [34]. Further, CaCO3 originates from calcium absorbed by plants from soil and fertilizers, where Ca is an essential macronutrient; during thermal treatment, calcium compounds crystallize as CaCO3 [35]. Similarly, the presence of KCl is attributed to the high potassium content of the vegetable biomass, since K is a key nutrient in plants and can form crystalline salts during pyrolysis [36]. It is noteworthy that although XRD clearly revealed the crystalline phases of SiO2, elemental Si was not detected in the EDS spectrum (Figure 1b). This discrepancy arises because of its relatively low concentration. Similar findings were reported by Ngernyen et al. [37], who reported that XRD patterns of both pristine and magnetic biochar revealed crystalline minerals such as SiO2, KCl, and CaCO3. However, the Si signal in EDS remained undetectable because of its low abundance.

Figure 3.

XRD pattern of the raw courgette-derive biochar, with reference diffraction peaks corresponding to SiO2, CaCO3, and KCl phases.

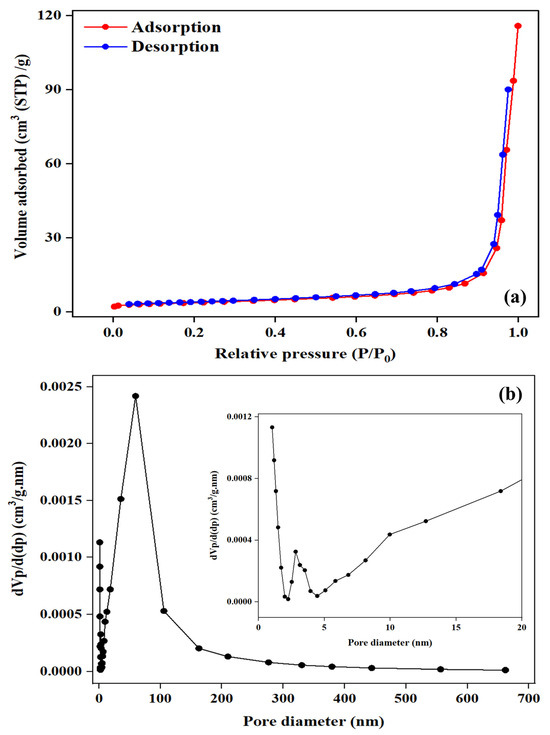

The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of the courgette-derived biochar (Figure 4a) exhibited a Type III isotherm according to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) classification, confirming the presence of internal pores [38]. The corresponding pore size distribution is shown in Figure 4b. The synthesized BC exhibited a modest SBET of 13.041 m2/g with a total pore volume of 0.1516 cm3/g. The average pore diameter obtained from the BET (slit model) was 23.249 nm, while the BJH average and median pore diameters were 58.938 and 52.532 nm, respectively. These values indicate a combination of mesopores (2–50 nm) and macropores (>50 nm), resulting in a hierarchically porous structure [39]. The coexistence of meso- and macropores enhances mass transfer and facilitates the diffusion of larger organic molecules during catalytic processes [40]. Zhang et al. [41] reported that biochars with modest surface areas within the range of single digits to about 10–20 m2/g can achieve excellent performance in catalytic applications. This activity is primarily attributed to their well-developed pore connectivity, surface heterogeneity, and the abundance of functional groups that promote electron transfer and active radical generation.

Figure 4.

(a) BET adsorption–desorption isotherm of the courgette-derived BC and (b) BJH pore size distribution profile (inset: enlarged view of the 1–20 nm range).

The pHpzc of the synthesized BC was quantified as 4.25 (Figure S1), highlighting the positive charge on the BC surface at pH < 4.25 and a negative charge at pH higher than this threshold. ATZ has a pKa of 1.68, meaning its amine group is protonated and positively charged at pH values below 1.68. Above this pH, ATZ exists chiefly in its neutral state [42]. At pH < 1.68, both ATZ and the BC surface are positively charged, resulting in electrostatic repulsion that hinders adsorption. In the pH range between 1.68 and 4.25, ATZ remains neutral while the BC surface is positively charged. Although electrostatic interactions are minimal in this range, adsorption may still occur through van der Waals forces and hydrophobic interactions [43,44]. At pH values above 4.25, the BC surface becomes negatively charged, while ATZ remains neutral. In this scenario, although direct electrostatic attraction is absent, adsorption may still be facilitated by polar interactions or hydrogen bonding [45].

2.2. Preliminary Control Experiments

2.2.1. Synergistic Effect of BC on PI Activation

The catalytic performance of the synthesized BC in activating PI was evaluated by comparing three reaction systems: BC alone, PI alone, and the combined BC/PI system, to evaluate the biochar synergistic activation effects. The experiments were carried out for 60 min at an initial ATZ concentration of 10 mg/L, a BC dosage of 0.5 g/L, a PI concentration of 2 mM, ambient temperature, and neutral pH. As shown in Figure 5a, the single BC system achieved an ATZ reduction of only 15.25% due to its modest surface area at 1000 rpm. The decrease in mixing speed to 200, 400, 600, and 800 rpm attained removal ratios of 6.3, 8.4, 9.1, and 10.3%, respectively, whereas the increase in mixing speed above 1000 rpm only achieved 15.6% removal efficiency. Therefore, 1000 rpm was determined as the optimal mixing speed due to its ability to attain sufficient interaction between the biochar and ATZ. In the sole PI system, 41.91% ATZ removal was achieved, primarily attributed to PI oxidation. The combined presence of BC and PI within the BC/PI system led to a marked improvement in ATZ removal percentage (74.1%). The limited ATZ removal and minor BC adsorption capacity (3.05 mg/g) in the single BC system demonstrated the slight role of self-adsorption in ATZ elimination. This can be ascribed to the lack of charge-charge interactions among the negatively charged BC (pHpzc = 4.25) and the neutral ATZ molecules (pKa = 1.68) under the experimental conditions (pH = 7) [46]. Nonetheless, the polar or hydrogen bonding interactions, along with the high porosity of the synthesized BC, likely mitigate this limitation. These attributes enhance the availability of adsorption sites and extend the contact duration, thereby promoting efficient mass transfer [47]. The modest degradation of ATZ observed when using PI alone suggests that the generated ROS were insufficient to drive the degradation process effectively which may be due to the relatively lower redox potential of PI (+1.6 V vs. NHE) [11]. Further, the PI consumption in the case of sole PI without an activator was limited, where the concentration of PI decreased from 2 mM to 1.8 mM, and iodate ion concentration was around 0.2 mM, which indicated the limited generation of iodate radicals and the modest degradation efficiency in this system. The enhanced catalytic efficiency of the BC/PI system is closely correlated with the physicochemical characteristics of the synthesized biochar and the production of ROS through PI activation at the active sites of BC. The SEM analysis revealed a rough and irregular surface with a hierarchically porous architecture (Figure 1a), which facilitates mass transfer and provides abundant contact sites for PI and ATZ molecules. The moderate surface area (13.041 m2/g) and the coexistence of meso- and macropores (23–59 nm) promote diffusion of reactants and the retention of reactive species, thereby accelerating oxidation. The EDS and XRD analyses demonstrated the presence of surface minerals such as CaCO3, KCl, and SiO2 (Figure 1b and Figure 3), which introduce electron-rich or positively charged sites that can facilitate electron transfer and enhance PI adsorption. Particularly, Ca2+ species on the BC surface improve the electrostatic affinity toward the negatively charged PI anions, thereby promoting its activation [6,12]. Moreover, the FTIR spectra (Figure 2) confirmed the presence of abundant oxygenated functional groups (–OH, –COOH, and C=O), which act as active redox centers for electron donation to PI. These groups facilitate the cleavage of the I–O bond in PI (bond length ≈ 1.78 Å), leading to the generation of multiple ROS, including •IO3, •OH, O2• −, and 1O2, as illustrated in Equations (1)–(6) [18]. The amorphous carbon matrix and surface heterogeneity further enhance charge transfer efficiency between BC and PI, supporting continuous ROS regeneration. The findings mentioned above underscore the indispensable roles of both BC and PI in the BC/PI oxidative system for ATZ degradation.

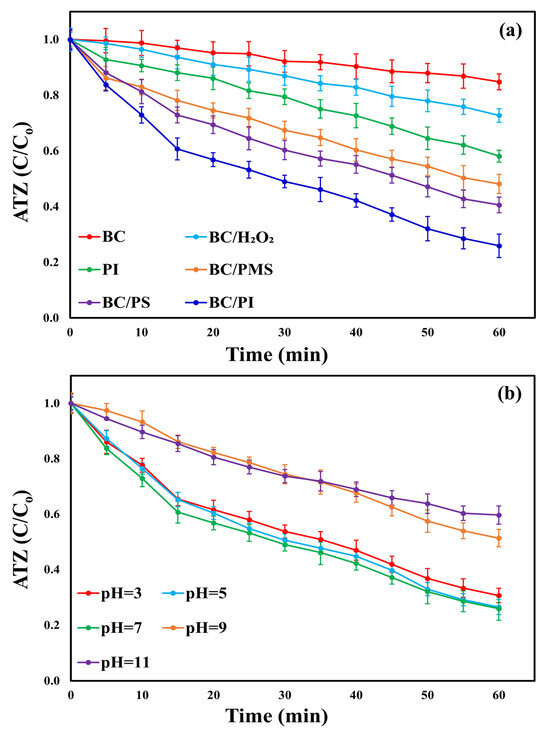

Figure 5.

(a) ATZ deterioration performance across different processes (Settings: [ATZ]o = 10 mg/L, [BC]o = 0.5 g/L, [PI]o = 2 mM, pH = 7, and T = 25 ± 0.5 °C) and (b) ATZ degradation at different pH values using the BC/PI system (Conditions: [ATZ]o = 10 mg/L, [BC]o = 0.5 g/L, [PI]o = 2 mM, and T = 25 ± 0.5 °C).

Additionally, the kinetic constants for pseudo-first-order reactions were determined to assess the effectiveness of BC in facilitating ATZ removal. The K values for the three systems (individual BC, sole PI, and combined BC/PI) were 0.0026 (R2 = 0.9942) min−1, 0.0085 (R2 = 0.9964) min−1, and 0.023 (R2 = 0.9934) min−1, respectively, as presented in Figure S2. The higher kinetic rate constants observed in the BC-catalyzed PI process, compared to the individual PI and BC systems, highlight the strong catalytic activity of BC toward PI, underscore the significant synergistic effect between PI and BC in the ATZ oxidative degradation, and validate the system’s oxidative efficiency in degrading various organic micropollutants. Moreover, the BC/PI system exhibited an ATZ degradation rate constant comparable to pollutants’ degradation rate constants reported in earlier biochar-based PI activation studies [26,28]. This observation underscores the comparable catalytic proficiency of the synthesized BC in facilitating PI activation.

Further, for a TOC level of 4.16 mg/L, the TOC mineralization efficiencies in the sole BC, single PI, and combined BC/PI systems were 6.92, 28.49, and 50.58%, respectively, as shown in Figure S3. These outcomes demonstrate that the BC-activated PI system achieved significantly greater mineralization compared to either PI or BC alone. The high TOC mineralization for the BC/PI degradation system could be owing to the generated reactive species that can attack ATZ and mineralize to simpler by-products and/or harmless compounds (e.g., CO2, H2O) as shown in Section 2.10. However, the lower TOC mineralization ratio, relative to the ATZ degradation percentage in the BC-catalyzed PI system, is likely due to ATZ intermediates that could generate during the degradation process, which were not fully mineralized [6,48]. This observation aligns with the findings by Naddeo et al. [49] and Li et al. [50], who reported lower TOC mineralization ratios than degradation percentages of organic pollutants in PI activation systems. Nevertheless, the current study exhibits a higher TOC mineralization ratio compared to previously reported PI-based AOPs. However, this cannot be considered as a superiority over other reports due to the different conditions in the previous PI-based AOPs, such as the pollutant concentration, PI dose, catalyst dose, and initial TOC concentration. For instance, Xiong et al. [10] achieved only 18.5% TOC removal despite 83.5% tetracycline degradation in the CuFeS2/PI system at PI dose of 0.8 mM, catalyst dose of 0.3 g/L, and pollutant concentration of 50 mg/L, while Li et al. [11] observed 45% TOC mineralization (Initial TOC 17.86 mg/L) alongside 82% decolorization of acid orange 7 dye in a granular activated carbon-PI activated system at PI dose of 10 mM and catalyst dose of 1 g/L.

Furthermore, the synergistic ratio of the BC-activated PI system for ATZ degradation was determined to be 2.07 (>1), indicating a pronounced synergistic interaction between BC and PI. This result confirms the enhanced performance of the combined BC/PI system over the individual use of BC or PI in improving PI activation and accelerating ATZ degradation [3,21].

2.2.2. Catalytic Activity of BC with Various Oxidants

The catalytic performance of the synthesized BC was assessed in conjunction with commonly used oxidizing agents in AOPs, including PMS, PS, and H2O2. The experiments were conducted under identical conditions with an initial ATZ concentration of 10 mg/L, a BC dosage of 0.5 g/L, an oxidant concentration of 2 mM, ambient temperature, and neutral pH. The ATZ degradation ratios for the BC-catalyzed PI, PS, PMS, and H2O2 treatment processes were 74.1%, 59.42%, 51.86%, and 27.28%, respectively (Figure 5a). The corresponding K values were 0.023 (R2 = 0.9934) min−1, 0.0156 (R2 = 0.9943) min−1, 0.0126 (R2 = 0.9931) min−1, and 0.005 (R2 = 0.9971) min−1, as presented in Figure S2. These results underscore the synthesized BC’s high efficiency in activating the tested oxidants and degrading ATZ, highlighting its broad catalytic potential. Additionally, the findings establish the relative oxidation capability of the investigated oxidants by the synthesized BC as follows: PI > PS > PMS > H2O2, consistent with previous BC-catalyzed AOPs [18,27]. The BC/H2O2 system exhibited the lowest ATZ degradation efficiency among the tested degradation processes, likely due to the strong O–O bond in H2O2, with a bond strength of approximately 213 kJ/mol, which hinders its cleavage by the synthesized BC [51]. The primary reactive species identified in the BC/H2O2 system were •OH radicals, while SO4• − radicals were predominant in the BC-activated PS and PMS systems, as shown in Figures S4–S6. In these experiments, specific radical scavengers (50 mM) were used to confirm the roles of different reactive oxygen species: tert-butanol for •OH, furfuryl alcohol for 1O2, and chloroform for O2• − [52,53]. Methanol was employed to simultaneously quench both SO4• − and •OH [54]. The reduced oxidation potential and half-life of •OH compared to SO4• − may explain the superior ATZ degradation efficiency observed in the BC-catalyzed PS and PMS systems relative to the BC/H2O2 system [53]. Additionally, the ATZ removal efficiency in the BC-catalyzed PS process surpassed that of the BC-catalyzed PMS process, potentially due to the weaker O–O bond in PS (d = 1.497 Å) compared to PMS (d = 1.453 Å). The weaker O–O bond in PS facilitates its activation and cleavage, enabling a more effective generation of ROS than PMS [24]. The consumption ratios of H2O2, PMS, PS, and PI in the BC-catalyzed AOPs were 23.53%, 52.02%, 65.63%, and 83.62%, respectively, as shown in Figure S7. PI exhibited the highest consumption ratio among the investigated oxidants, indicating the synthesized BC’s strongest affinity for PI. This affinity facilitated the generation of a greater quantity of ROS, resulting in enhanced oxidation performance and higher ATZ removal efficiency [27]. Furthermore, the long I–O bond length in the PI molecule (1.78 Å) contributes to its easier activation and cleavage, promoting ROS production [24]. The effective interaction between PI and the biochar could be further due to the structure of the biochar, where it has positive calcium ions on the surface that can improve the affinity of PI towards the biochar’s surface. Consequently, PI proved to be the most effective tested oxidant, with the BC/PI system demonstrating superior oxidation performance compared to the other oxidation methods. Therefore, the BC/PI system was selected for subsequent experiments.

2.3. Assessment of Iodinated By-Product Formation

A critical challenge in implementing PI activation processes for water treatment lies in the potential generation of I-DBPs during the degradation process. Toxic I-DBPs, such as hypoiodous acid (HOI), iodide ions (I−), molecular iodine (I2), and triiodide ion (I3−), are of particular concern due to their high reactivity and potential to form secondary toxic compounds. These species can participate in halogenation reactions with NOM or pollutants, generating organoiodine compounds that are more toxic, persistent, and less biodegradable. Prolonged exposure to such I-DBPs has been associated with adverse effects on human health, including thyroid dysfunction, cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, and potential carcinogenicity. Therefore, their formation during PI-based AOPs must be carefully avoided to ensure both environmental safety and public health protection [15,55]. In this study, the potential generation of harmful iodine-containing species throughout ATZ degradation in the BC/PI system was evaluated by monitoring the concentrations of IO4− and IO3− ions under the following conditions: an initial ATZ concentration of 10 mg/L, a BC dosage of 0.5 g/L, a PI concentration of 2 mM, ambient temperature, and neutral pH (Figure S8). The results demonstrated that during ATZ degradation, IO4− was gradually consumed, accompanied by a corresponding increase in IO3− concentration, indicating a nearly complete stoichiometric conversion of IO4− to IO3−. This observation implies that the formation of potentially hazardous reactive iodine species did not occur. Instead, the process predominantly generated IO3−, a stable and nontoxic iodine species typically present in iodized salt. Further, this supports the conversion of most of PI ions to iodate radicals which explains the high degradation efficiency in the BC/PI system. These outcomes affirm the sustainability and safety of the proposed treatment process, highlighting its suitability for real-world water purification applications without posing risks to public health or the environment. Similar results were noted in prior PI-based AOP studies [17,22,23].

2.4. Effect of pH

The pH value significantly influences the distribution of reactive species and thereby affects pollutant degradation [56]. A sequence of tests was employed at different pH levels to investigate the impact of pH on ATZ breakdown ratios and kinetic rate constants within the BC/PI process, as shown in Figure 5b and Figure S9, respectively. The experiments were performed for 60 min under the following conditions: ([ATZ]o = 10 mg/L, T = 25 ± 0.5 °C, [BC]o = 0.5 g/L, and [PI]o = 2 mM). ATZ degradation ratios were 69.35, 73.53, 74.1, 48.67, and 40.33% at pH levels of 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11, respectively. The associated rate constants were 0.0201 (R2 = 0.9948) min−1, 0.022 (R2 = 0.996) min−1, 0.023 (R2 = 0.9934) min−1, 0.0106 (R2 = 0.9938) min−1, and 0.0092 (R2 = 0.9964) min−1.

The findings demonstrate that ATZ degradation in the BC/PI system is more efficient under neutral and acidic conditions, while significant inhibition is observed under alkaline conditions. This behavior may be due to the reduced reduction potential of the PI species in basic solutions (+0.7 V vs. NHE) compared to its higher potential in acidic solutions (+1.6 V vs. NHE) [11]. Furthermore, under strongly acidic conditions, hydrogen ions (H+) interact with unpaired electrons on the synthesized BC surface, generating hydrogen atoms (H•), which subsequently react with IO4− to produce IO3•, as described in Equations (7) and (8) [57]. However, the generated H• can also scavenge IO3•, reducing it to IO3−, as outlined in Equation (9) [11]. In contrast, the decline in ATZ degradation efficiency and reaction rate constants in alkaline conditions is attributed to the formation of hydrogen diperiodate ions (H2I2O104−), which is the dominant PI species at pH > 8. This species exhibits lower reactivity and reduced redox potential compared to IO4− [20,58]. These findings align with previous PI based-AOPs [16,18]. The ATZ removal ratios in acidic and neutral solutions showed no significant difference. As a result, subsequent investigations were carried out under neutral pH to reduce the cost associated with pH adjustments.

This pH-dependent behavior can be rationalized by the interplay between the structural and surface properties of the synthesized biochar and the chemical speciation of PI. The synthesized BC possesses a pHpzc of 4.25, meaning that its surface carries a positive charge under acidic conditions and becomes negatively charged at higher pH. At pH ≤ 7, the positively charged BC surface electrostatically attracts the negatively charged IO4− species, promoting their adsorption and subsequent activation on active sites enriched with oxygen-containing functional groups (–OH, –COOH, C=O) as confirmed by FTIR analysis (Figure 2). These groups facilitate electron transfer from the biochar to PI, promoting the generation of ROS such as •IO3, •OH, O2• −, and 1O2, which drive ATZ oxidation. On the other hand, the presence of calcium on the biochar surface, as evidenced by the XRD pattern (Figure 3) and EDS spectrum (Figure 1a), can promote interactions between the negatively charged PI anions and the biochar surface under acidic and neutral conditions, while the degradation efficiency declined at alkaline conditions owing to the competition between PI and hydroxyl ions on the biochar’s surface. The enhancement of the interaction between the biochar and PI at neutral and acidic conditions can improve the generation of reactive species, thereby ameliorating the degradation performance.

2.5. Influence of Temperature

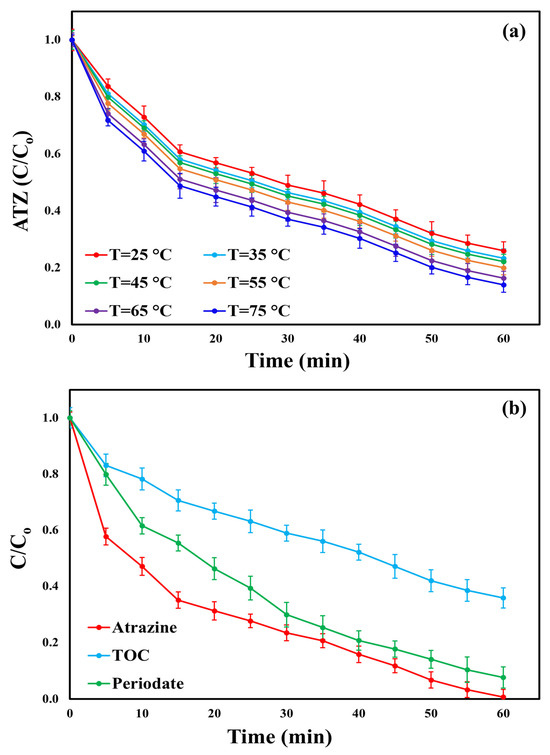

The removal efficiency of ATZ was assessed across different values of reaction temperatures (25, 35, 45, 55, 65, and 75 °C) in the BC/PI system under the following conditions: [ATZ]o = 10 mg/L, [BC]o = 0.5 g/L, [PI]o = 2 mM, pH = 7, and a treatment period of 60 min. As illustrated in Figure 6a, ATZ degradation increased slightly with temperature, achieving efficiencies of 74.1, 76.73, 77.92, 80.08, 83.7, and 86.06% at 25, 35, 45, 55, 65, and 75 °C. The corresponding reaction rates increased from 0.023 (R2 = 0.9934) min−1 at 25 °C to 0.0247 (R2 = 0.9925) min−1, 0.0256 (R2 = 0.9922) min−1, 0.0273 (R2 = 0.9916) min−1, 0.0303 (R2 = 0.991) min−1, and 0.0326 (R2 = 0.9907) min−1 at 25, 35, and 45 °C, respectively (Figure S10). This increase in ATZ removal and kinetic rate constants with temperature is likely due to thermal activation and increased molecular motion, which facilitates PI activation, generates more ROS, and improves ATZ degradation [19]. Similar results were documented by Chen et al. [14], who observed increased tetracycline removal efficiency and K values with rising temperatures in a system using nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes encapsulating cobalt (Co@NCNTs) for PI activation. The enhancement in ATZ degradation with temperature can be attributed not only to thermal activation but also to the intrinsic structural and compositional characteristics of the biochar catalyst. The courgette-derived BC possesses a rough and irregular surface with a hierarchical pore structure comprising both mesopores and macropores. Such textural features facilitate efficient diffusion and adsorption of ATZ molecules, ensuring that temperature-induced molecular motion translates effectively into enhanced surface interactions [59]. Moreover, the BC surface is rich in oxygen-containing functional groups, which serve as active sites for electron transfer and radical generation during PI activation. These functional moieties likely become more reactive at elevated temperatures, promoting faster electron exchange and thereby enhancing the formation of ROS, which are primarily responsible for ATZ oxidation [6,12]. In addition, the mineral phases identified in the XRD analysis (SiO2, KCl, and CaCO3) may contribute synergistically to the catalytic process. Calcium carbonate can facilitate surface redox reactions by providing active sites that promote electron exchange and enhance interfacial charge transfer, while SiO2 provides structural stability and enhances surface roughness, thereby increasing the available reaction interface. The presence of KCl also promotes ionic conductivity, which may accelerate the charge transfer processes during PI activation [60,61,62]. Collectively, these physicochemical features explain the observed temperature-dependent enhancement in catalytic performance, beyond simple kinetic acceleration due to increased molecular motion. The Arrhenius equation (Equation (10)) was implemented to determine the activation energy (Ea) for the oxidative degradation of ATZ in the BC/PI system [63]. As shown in Figure S11, the Ea for ATZ removal in the BC/PI process was calculated as 5.93 kJ/mol. This value is significantly less than the Ea results reported for ATZ degradation in previously studied AOPs (Table S3). For instance, the heat/PS system reported by Ji et al. [2] exhibited an Ea of 141 kJ/mol, while the heat/PS system reported by Jiang et al. [1] showed a similarly high Ea of 102 kJ/mol. In comparison, biochar/nanoscale zero-valent iron (nZVI)/PS systems, such as soybean stalk biochar/nZVI/PS and soybean straw-derived biochar/sulfurized nZVI/PS, showed activation energies of 83.34 and 47.63 kJ/mol, respectively [64,65]. The remarkably low Ea obtained in this study underscores the superior energy efficiency of the BC/PI system and reflects the intrinsic reactivity of the biochar surface. The presence of abundant surface defects, heteroatoms, and redox-active mineral phases facilitates spontaneous PI activation with minimal external energy input. Consequently, the BC/PI system demonstrates a highly favorable thermodynamic profile for ATZ oxidation, confirming that the unique structural and chemical attributes of the courgette-derived BC play a pivotal role in achieving efficient catalytic performance even under mild conditions.

where K is the kinetic rate constant (s−1), T indicates the reaction temperature (Kelvin), R indicates the molar gas constant (R = 8.3145 J/mol.K), and A is the pre-exponential factor.

Figure 6.

(a) ATZ degradation at different temperatures using the BC/PI system (Conditions: [ATZ]o = 10 mg/L, [BC]o = 0.5 g/L, [PI]o = 2 mM, and pH = 7) and (b) ATZ degradation, TOC mineralization, and PI consumption ratios utilizing the BC/PI system under the optimal settings (pH = 7, [ATZ]o = 7.3 mg/L, T = 25 ± 0.5 °C, [BC]o = 0.55 g/L, and [PI]o = 2.7 mM).

Given the minor variations in removal efficiency with increasing temperature, subsequent experiments were performed at 25 °C to represent environmentally relevant and energy-efficient operational conditions.

2.6. Model Generation

2.6.1. Statistical Analysis

Equation (11) represents the quadratic model relating ATZ removal efficiency to the ATZ starting concentration (X, mg/L), PI initial concentration (Y, mM), and the BC dosage (Z, g/L). The high R2 value of 0.9494 indicates a strong correlation and demonstrates the model’s effectiveness in capturing the influence of operating parameters on ATZ removal. However, the obtained model is restricted to the ranges of operating parameters in Table 1, as the model was developed based on the experiments in Table 2, and this model cannot describe the prediction of an experiment outside this range.

ATZ removal efficiency = 52.5 − 5.21 X − 2.1 Y + 123.4 Z + 0.331 X2 + 6.04 Y2 + 7.1 Z2 − 0.917 XY − 4.19 XZ − 4.4 YZ

Table 1.

Settings of the practical design.

Table 2.

Experimental and predicted ATZ removal efficiencies under varying operational conditions.

The measured ATZ removal ratios and the corresponding removal percentages calculated from the polynomial equation across the 20 experiments are summarized in Table 2. The minimal deviation between the measured and calculated ATZ removal percentages validates the reliability and accuracy of the model. The ANOVA was conducted using Minitab® 22 to verify the statistical adequacy, predictive reliability, and overall significance of the developed response surface model, the results of which are summarized in Table 3. The R2 value of 94.94% and the adjusted R2 of 90.38%, both approaching unity, demonstrate the strong reliability and predictive capability of the regression model. Additionally, the minimal difference between the two coefficients (4.56%) reflects excellent agreement between the predicted and experimental values, confirming that the fitted polynomial model provides a statistically sound representation of the system. This consistency validates the model’s adequacy in describing the effects of the experimental variables on ATZ removal efficiency within the BC/PI system. Furthermore, the high R2 value indicates that approximately 94.94% of the total variation in ATZ removal efficiency is captured by the model, with only about 5% remaining unexplained, thereby reinforcing its robustness. The model’s overall statistical significance was further supported by a high F-value (20.83) and a very low p-value (<0.05), confirming the strong correlation between the observed and predicted responses (Table 2). In addition, most of the model terms exhibited p-values below 0.05, signifying that they exerted statistically significant influences on the response. Among the examined operational parameters, the BC dose had the most substantial impact on ATZ removal efficiency. This is reflected by the highest F-value of 83.84. The initial ATZ concentration ranked second in significance, showing a notable influence with an F-value of 51.49. In contrast, the initial PI concentration had the least effect on ATZ removal efficiency. This is evident from the lowest F-value of 38.53, as depicted by the ANOVA results.

Table 3.

The ANOVA results of the RSM-CCD model.

2.6.2. Validation of the Model

The optimal operating values of the independent parameters were identified using the response optimizer function in the Minitab® 22 statistical software, with the objective of maximizing the ATZ removal efficiency as the target response. The resulting optimal values were 7.3 mg/L for [ATZ]o, 2.7 mM for [PI]o, and 0.55 g/L for [BC]o, as outlined in Table 4. These optimized conditions were subsequently employed in the following experimental investigations.

Table 4.

Data derived from the RSM-CCD model.

To further validate the reliability of the generated model, an additional investigation was conducted utilizing the BC/PI process under the optimum conditions (pH = 7, [pollutant]o = 7.3 mg/L, T = 25 ± 0.5 °C, [BC]o = 0.55 g/L, and [PI]o = 2.7 mM) for a 60 min process time. The measured ATZ degradation efficiency of 99.35% (Figure 6b) was closely aligned with the calculated value of 99.19%, as presented in Table 4. This strong agreement reinforces the model’s precision and applicability. The pseudo-first-order kinetic rate constant of ATZ removal was 0.0601 (R2 = 0.9462) min−1 (Figure S12). Additionally, the TOC mineralization ratio of ATZ reached only 64.23% (Figure 6b). Complete mineralization could not be attained because of the formation of ATZ intermediates, which maintain a high total organic load in solution and require extended time for generating additional ROS to further degrade these by-products [18]. The PI consumption ratio of 92.38% (Figure 6b) demonstrates the efficient activation of PI within the BC/PI system. This activation generates ROS, which is crucial in promoting ATZ breakdown and facilitating TOC mineralization. To demonstrate the catalytic efficiency of the courgette-derived BC, a performance comparison between the synthesized catalyst and previously reported materials used for PI activation in the degradation of various organic pollutants has been conducted. As explained in Table 5, the comparison indicates that the courgette-derived BC exhibits comparable or even superior catalytic performance, underscoring its potential as a sustainable and efficient activator for PI-based oxidation processes.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of courgette-derived biochar with previously reported materials for PI activation in the degradation of various organic pollutants.

Furthermore, a comparison of the BC/PI system developed in this study with previously reported AOPs for ATZ degradation was carried out to demonstrate its superior efficiency and practical applicability. As summarized in Table 6, the BC/PI system achieved a 99.35% ATZ removal efficiency within 60 min under the conditions ([PI]o = 2.7 mM, [ATZ]o = 7.3 mg/L, pH = 7, [BC]o = 0.55 g/L, and T = 25 ± 0.5 °C). On the other hand, the PS activation system using spinach-derived biochar achieved a slightly higher degradation ratio of 99.8%; however, it required 120 min to reach this efficiency, which is double the time required by the BC/PI system [6]. Similarly, the photocatalysis system utilizing graphene-promoted graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) nanosheets achieved complete degradation (100%), but required 300 min, highlighting the BC/PI system’s significant advantage in degradation speed [67]. Other methods, such as the PMS activation process employing copper cobalt oxide (CuCo2O4) nanoparticles, exhibited a comparable removal of 99% within 30 min [9]. However, experimental settings like the slightly acidic pH of 6.8 and the specific catalyst used, may limit its applicability. In contrast, The BC/PI system operates under a neutral pH, which is more environmentally friendly and versatile for real-world applications. In comparison to less effective AOPs, the Fenton-like process using nZVI achieved only a 50% ATZ removal ratio within 120 min [8]. Additionally, the electrooxidation/H2O2 system demonstrated a lower removal efficiency of 45.42% in 90 min [68]. These methods not only required more time but also exhibited reduced degradation performance, underscoring the superior efficiency and kinetics of the BC/PI system. Furthermore, while the ozone oxidation process employing cerium dioxide (CeO2) achieved rapid degradation with a degradation percentage of 85.5% in just 10.0 min, its overall efficiency was lower than that of the BC-catalyzed PI process [4]. The suggested process combination of high efficiency, reasonable kinetics, and compatibility with neutral pH conditions highlights its potential as a promising and practical approach for ATZ degradation.

Table 6.

Performance comparison of the BC/PI system with other AOPs for ATZ degradation.

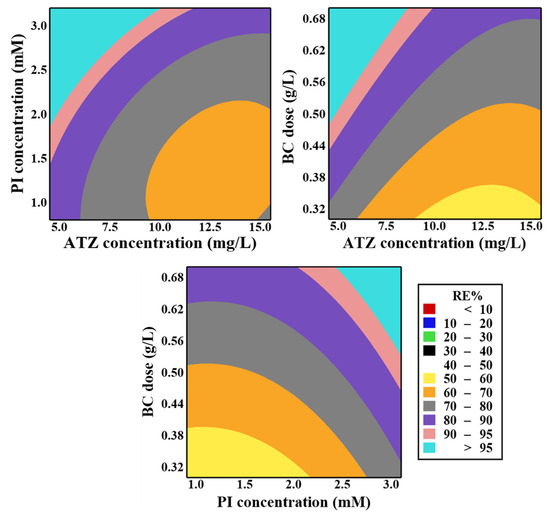

2.6.3. Effects of Independent Parameters

The effects of the investigated parameters in the RSM-CCD model (ATZ concentration, PI concentration, and BC initial dose) on ATZ degradation efficiency are depicted in Figure 7. The results revealed that increasing BC dosage up to the optimal level of 0.55 g/L enhanced ATZ removal efficiency. Increasing the initial BC dose enhances the BC surface area, thereby expanding the active sites available for ATZ adsorption and PI activation. As a result, the generation of ROS is intensified, significantly promoting the oxidative degradation of ATZ [29]. Moreover, increasing the BC dose increases the number of oxygen-containing functional groups in the reaction solution, which in turn facilitates the generation of additional ROS [69]. However, exceeding the optimum dosage led to a decline in ATZ removal efficiency, likely due to the agglomeration of BC particles. Such aggregation diminishes the beneficial effect of overdosing by reducing the active surface area and, consequently, limits the generation of ROS, thereby weakening the system’s oxidative performance [25].

Figure 7.

Contour curves of the impacts of [ATZ]o, [BC]o, and [PI]o on ATZ degradation ratio employing the BC-catalyzed PI process.

At lower ATZ concentrations (<7.3 mg/L), its degradation efficiency improved because the number of generated ROS is sufficient relative to the fewer ATZ molecules. This ensures more effective interactions and facilitates the degradation process [33]. Conversely, when the ATZ concentration surpassed 7.3 mg/L, its degradation efficiency declined. This decrease can be attributed to the increased number of ATZ molecules, which demand a greater quantity of ROS to achieve effective degradation [6]. Additionally, increased ATZ concentrations lead to greater production of its by-products, which compete with ATZ for active sites, thereby reducing the ATZ removal efficiency [19]. Moreover, increasing the initial concentration of ATZ may result in its buildup on the reactive locations of the BC, potentially hindering the generation of ROS [59].

Elevating the PI concentration up to its optimal concentration of 2.7 mM improved the efficiency of ATZ removal. This improvement can be attributed to the accelerated catalytic oxidation that is facilitated by the elevated number of IO4− ions in the reaction solution, which promotes the generation of ROS, thereby increasing ATZ degradation [30]. Nevertheless, when the PI concentration was oversupplied (>optimal level), the ATZ removal efficiency declined. Excess IO4− may compete with ATZ and its intermediates for reactive species, forming less reactive by-products. It reacts with •OH and •IO3, diverting them from degradation pathways and reducing their availability for ATZ oxidation (Equations (12) and (13)) [70,71]. Additionally, excess IO4− promotes the formation of stable compounds such as dimeric iodate (I2O6) and dimeric periodate (I2O8), which do not contribute to oxidative reactions (Equations (14) and (15)) [18]. Furthermore, at elevated PI concentrations, the active sites on the BC surface become insufficient to achieve complete PI activation, resulting in decreased ATZ removal efficiency [17].

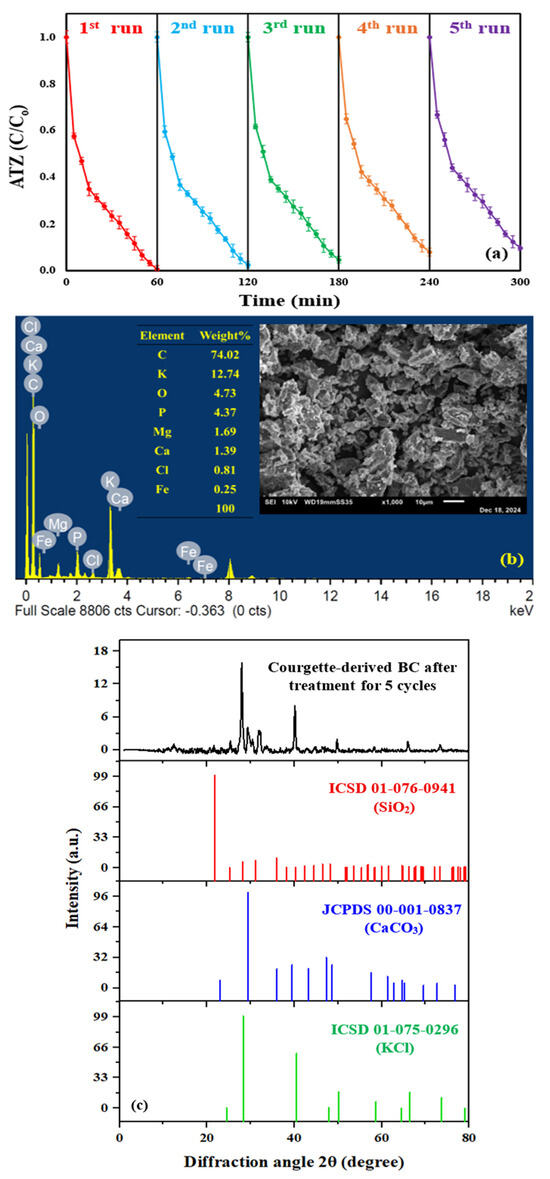

2.7. Recyclability of the Synthesized Biochar

Recycling experiments were conducted for five successive runs under the optimum conditions to evaluate the reusability of the synthesized biochar. BC particles were collected after each cycle by vacuum filtration with a 0.22 μm membrane filter and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min, after which the supernatant was discarded. The catalyst powder was thoroughly washed and centrifuged multiple times with ultrapure water and ethanol until the supernatants became colorless, ensuring the removal of any adsorbed pollutant particles. This process ensured the removal of any adsorbed pollutant particles. The cleaned BC powder was subsequently dehydrated at 60 °C for 24 h. For each reuse cycle, the dried powder was introduced into a freshly prepared ATZ degradation solution [29,48]. The yielded ATZ removal efficiencies across the successive runs were 99.35, 97.5, 95.33, 92.03, and 90.27%, respectively, corresponding to an overall reduction of approximately 9% in ATZ removal efficiency, as shown in Figure 8a. In comparison to previous studies on biochar-based PI activation, He et al. [16] observed a 17.5% decline in diclofenac sodium removal efficiency after five repeated cycles (80 min) employing the UV/sewage sludge-derived biochar/PI system. Additionally, Seo et al. [31] reported a 20% reduction in organic pollutant degradation efficiency after five consecutive runs (60 min) utilizing the seaweed-derived biochar/PI system. In contrast, the limited decrease in ATZ removal efficiency in the current study highlights the superior stability and reusability of the synthesized BC. This high reusability likely results from the wealth of functional groups on the BC surface that facilitate strong interactions with PI and support repeated cycles of effective electron transfer without significant breakdown of the BC’s structure. These groups also provide reactive sites that help retain PI molecules, thus enabling efficient degradation of contaminants over multiple uses. Additionally, the porous structure of BC enhances its ability to adsorb both PI and the target pollutant, maximizing the contact area and interaction frequency necessary for catalytic reactions [17,29]. However, minor declines in ATZ degradation efficiency over multiple cycles may be attributed to the gradual loss of BC particles during the recovery process [71]. As depicted in Figure S13, the mass of BC introduced into the fresh ATZ solution exhibited a gradual decline over successive run. Initially set at 0.55 g/L, the BC mass decreased to 0.5336, 0.51876, 0.4969, and 0.4803 g/L, corresponding to catalyst mass loss percentages of 2.98, 5.71, 9.66, and 12.67% after the second, third, fourth, and fifth runs, respectively. Additionally, blockage of the active sites throughout the repeated runs by ATZ or its generated by-products could decrease the ATZ removal ratios across the cycles [18]. The degradation kinetics were evaluated across the five consecutive runs, yielding reaction rate constants of 0.0601 (R2 = 0.9462) min−1 for the 1st run, 0.0516 (R2 = 0.9797) min−1 for the 2nd run, 0.046 (R2 = 0.9874) min−1 for the 3rd run, 0.0402 (R2 = 0.99) min−1 for the 4th run, and 0.0377 (R2 = 0.9903) min−1 and for the 5th run (Figure S14). These rates align well with the observed ATZ removal efficiencies across the runs. The high R2 values demonstrate strong correlations, confirming consistent degradation performance throughout the cycles. Furthermore, SEM, EDS, and XRD analyses of the BC particles after five consecutive degradation cycles were conducted (Figure 8b,c). No significant changes were observed in the XRD diffraction peaks, EDS composition, or SEM morphology of BC after degradation, indicating that the catalyst maintained its stability across the five runs. Thus, the system demonstrated excellent reusability, with only minor performance losses mainly due to catalyst recovery limitations rather than intrinsic deactivation. The decreased porosity in SEM images and the reduced intensities of XRD peaks confirmed ATZ adsorption on the BC surface.

Figure 8.

(a) ATZ degradation ratios using the BC/PI system in five successive runs (pH = 7, [Pollutant]o = 7.3 mg/L, T = 25 ± 0.5 °C, [BC]o = 0.55 g/L, and [PI]o = 2.7 mM), (b) EDS pattern of the synthesized BC after treatment for five successive cycles (inset: SEM image), and (c) XRD pattern of the courgette-derive biochar after treatment.

2.8. Identification of Dominant ROS in the BC/PI System

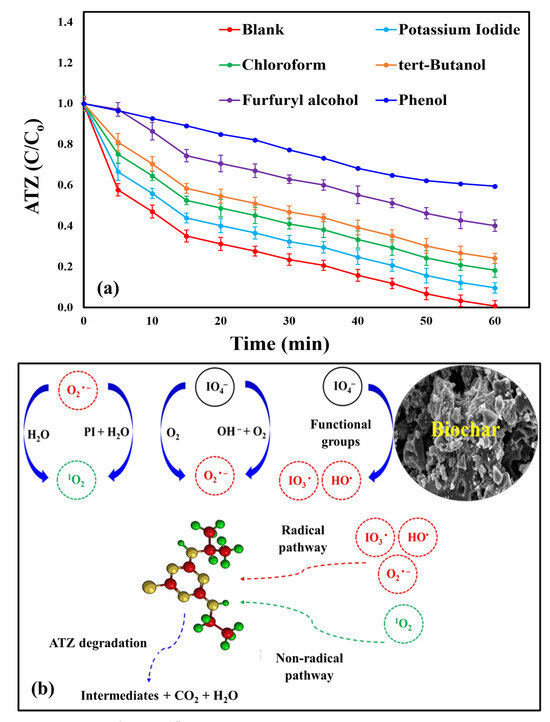

To elucidate the relative contribution of ROS to ATZ degradation within the proposed system, quenching experiments were conducted under the optimum reaction conditions. Excess amounts (50 mM) of several scavenging agents were added to the ATZ reaction mixture prior to initiating the reaction to perform quenching tests. The scavengers used included potassium iodide, chloroform, tert-butanol (kinetic rate: 7.6 × 108 M−1S−1), furfuryl alcohol (Kinetic rate: 1.2 × 108 M−1S−1), and phenol, targeting surface-bound radicals, O2• −, •OH, 1O2, and (•OH and •IO3), respectively [52,53]. As shown in Figure 9a, ATZ degradation was slightly reduced from 99.35% for the blank sample (without scavengers’ additions) to 90.44% with potassium iodide, indicating limited involvement of surface-bound radicals in the degradation reaction. Chloroform and tert-butanol had stronger inhibitory effects, reducing ATZ degradation to 81.8 and 75.94%, respectively, suggesting minor roles for O2• − and •OH. The most substantial decreases occurred with furfuryl alcohol and phenol, reducing ATZ degradation ratios to 59.88 and 40.56%, respectively, highlighting the major roles of •IO3 and 1O2 in PI activation. Kinetic studies further supported these findings, as degradation rate constants declined from 0.0601 (R2 = 0.9857) min−1 for the control to 0.038 (R2 = 0.9857) min−1, 0.0289 (R2 = 0.9857) min−1, 0.0244 (R2 = 0.9857) min−1, 0.0153 (R2 = 0.9857) min−1, and 0.0094 (R2 = 0.9857) min−1 with potassium iodide, chloroform, tert-butanol, furfuryl alcohol, and phenol, respectively, as presented in Figure S15. Previous studies on catalytic PI-activated systems for the degradation of organic pollutants have reported comparable outcomes [22,72]. In future work, electron spin resonance (ESR) measurements and chemical probe analyses will be integrated with scavenging experiments to provide further confirmation of the degradation mechanism.

Figure 9.

(a) ATZ degradation efficiency using the BC/PI process with various scavengers (Conditions: pH = 7, [ATZ]o = 7.3 mg/L, T = 25 ± 0.5 °C, [quencher]o = 50 mM, [BC]o = 0.55 g/L, and [PI]o = 2.7 mM) and (b) proposed ATZ degradation mechanism by the BC/PI system.

2.9. Possible ATZ Degradation Mechanism

The structural and surface properties of the courgette-derived BC play a vital role in facilitating electron transfer from the BC surface to PI ions during the activation process. The partially graphitized carbon structure and interconnected porous morphology observed in the SEM image (Figure 1a) facilitate efficient electron mobility across the BC surface, promoting rapid charge transfer during PI activation [12]. Moreover, the EDS analysis (Figure 1b) revealed a significant presence of potassium, which facilitates electron transfer within the BC/PI system. Potassium can interact with the surface oxygen groups, improving charge delocalization. Further, its electrostatic effect enhances polarization between the BC and PI ions, thereby accelerating electron transfer within the BC/PI system [54]. Additionally, FTIR analysis (Figure 2) confirmed the presence of abundant oxygen-containing functional groups (–OH, C=O, and C–O), which serve as redox-active sites capable of donating electrons to PI ions. This electron donation promotes the reduction in PI and the efficient generation of various ROS, thereby achieving superior ATZ degradation performance [6]. Electron transfer from the biochar to periodate ions initiates their activation and subsequent decomposition, leading to the formation of •IO3 and •OH radicals that facilitate pollutant degradation, Equations (1) and (2) [17,71]. Further, O2• − could be produced through the reaction of dissolved oxygen (O2), IO4−, and hydroxyl ions (OH−) or the reaction between OH− and IO4− only, as shown in Equations (3) and (4) [18]. Moreover, 1O2 can be generated through the interaction between O2• − and water molecules (H2O), and IO4− or the reaction of O2• −, H2O only, as depicted in Equations (5) and (6) [18]. Ultimately, the generated ROS could degrade ATZ into CO2, H2O, and intermediate products. Figure 9b provides an overview of the ATZ decomposition mechanism in the BC-catalyzed PI process.

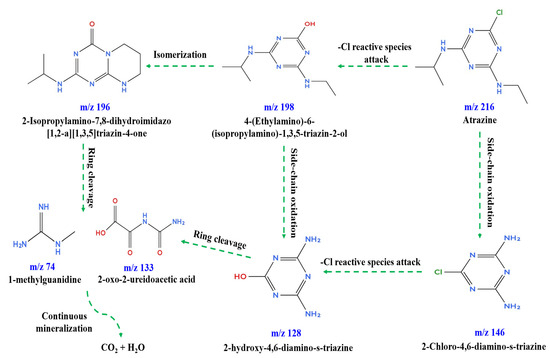

2.10. Proposed ATZ Degradation Pathways

The m/z peaks of the intermediates formed during ATZ degradation in the BC/PI system are shown in Figure S16, and the corresponding compound details are summarized in Table S4. Based on the identified degradation intermediates, the possible ATZ degradation pathways were proposed, as illustrated in Figure 10. The formation of product P6 (m/z = 198) is attributed to the ROS-induced dechlorination of ATZ (P7, m/z = 216), while isomerization of P6 produced the by-product P5 (m/z = 196) [73,74]. Side-chain oxidation of ATZ generated the intermediate P4 (m/z = 146) [2]. The by-product P2 (m/z = 128) formed from either side-chain oxidation of P6 or ROS attack and dechlorination of P4 [75]. Ring cleavage of P2 and P5 by-products produced the intermediates P3 (m/z = 133) and P1 (m/z = 74), respectively [5]. Successive radical attacks on the generated by-products could lead to their mineralization to CO2 and H2O [6,76]. The evaluation of the toxicity of the generated by-products was performed using the toxicity estimation software tool (TEST) (version 5.1.2) towards Daphnia magna and fathead minnow by estimating the half-lethal concentration (LC50) as shown in Table S5. The results in Table S5 indicate that the generated intermediates have lower toxicity compared to ATZ, except for P4 in the case of Daphnia magna. The reduction in toxicity demonstrates the potential of the degradation system to convert the toxic organic pollutants to intermediates with limited toxicity.

Figure 10.

Proposed ATZ degradation pathways.

2.11. Environmental Significance and Practical Application

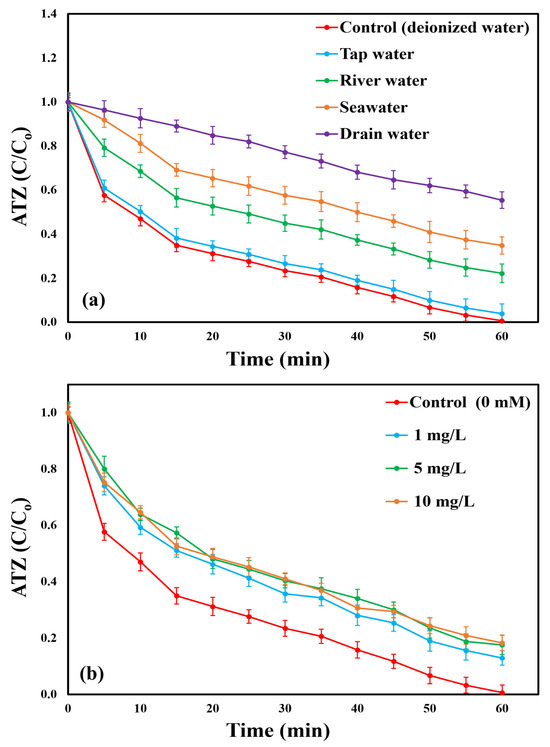

2.11.1. Effect of Coexisting Water Components

Real wastewater typically contains a complex mixture of inorganic ions and organic substances that can interfere with the catalytic degradation of organic pollutants [77]. To simulate real treatment conditions, several natural water matrices, including ultrapure water, tap water, seawater, lake water, and drain water, were employed as reaction media for the degradation of ATZ in the BC/PI system. The sampling locations of the collected wastewater are provided in Text S1, and their corresponding physicochemical properties are summarized in Table S6. All experiments were conducted for 60 min at pH 7 and a reaction temperature of 25 ± 0.5 °C. A volume of 100 mL from each water matrix was used as the reaction medium in place of ultrapure water (control). Each sample was spiked with identical concentrations of ATZ (10 mg/L), catalyst (0.5 g/L), and PI (2 mM) to initiate the degradation process. In comparison with a 99.35% ATZ removal ratio in ultrapure water, degradation ratios declined to 96.09, 77.8, 65.15, and 44.6% for tap water, river water, seawater, and drain water, respectively (Figure 11a). Correspondingly, reaction rate constants decreased from 0.0601 (R2 = 0.9462) min−1 in ultrapure water to 0.0478 (R2 = 0.9857) min−1, 0.0257 (R2 = 0.9917) min−1, 0.0179 (R2 = 0.9964) min−1, and 0.0094 (R2 = 0.9967) min−1, respectively, as illustrated in Figure S17. The reduced ATZ degradation observed in these real water matrices is likely due to the inhibitory effects of coexisting dissolved organic matter, inorganic ions (reflected by TDS and electrical conductivity), and turbidity [78]. Dissolved organics can compete with ATZ for ROS, reducing the availability of ROS for ATZ degradation [79]. Furthermore, inorganic ions may react with ROS to produce radicals with lower oxidation potential, decreasing the system’s overall reactivity [53]. Additionally, organic compounds and inorganic ions may block active sites on the BC surface, slowing down ROS generation and consequently reducing ATZ degradation [5]. Suspended particulate matter responsible for turbidity can scavenge or physically adsorb ROS and pollutants. It may also obstruct active sites on the BC surface, limiting the number of available catalytic sites. Furthermore, particulate matter can hinder effective interactions between the organic pollutant, catalyst, and oxidant. These combined effects ultimately lead to a reduction in the apparent degradation rate [80]. A statistical comparison between the measured matrix properties and removal efficiencies reveals a very strong inverse relationship with dissolved organic content: as TOC increases across the matrices (ultrapure 4.16 → tap 18.27 → river 52.06 → seawater 71.35 → drainage 123.28 mg/L), ATZ removal declines almost monotonically. This trend aligns with the competitive scavenging behavior of ROS by dissolved organic matter. High ionic strength is further implicated in the reduced reactivity observed for seawater and drainage samples. Seawater exhibits very high conductivity and TDS (1618.27 μS/cm and 2815.65 mg/L, respectively), while drainage water also shows elevated values (523.52 μS/cm; 939.87 mg/L). These mechanisms likely explain the pronounced decrease in rate constants and overall removal in seawater and drainage matrices relative to ultrapure water. In addition, turbidity exhibited a clear negative correlation with degradation performance. Water matrices with higher turbidity levels, such as drainage (29.49 NTU) and river water (16.26 NTU), showed significantly lower rate constants and removal efficiencies. The strong inverse relationship observed in our dataset indicates that turbidity plays a major inhibitory role in the degradation process. By contrast, pH differences among matrices in our study are small (ranging from 6.57 to 8.43) and show no clear systematic relationship with removal efficiency in this dataset. While pH can modulate radical speciation and catalyst surface charge, the dominant inhibitory factors here appear to be dissolved organic matter and matrix ionic/particulate load. Taken together, these findings indicate that TOC content and turbidity are the main factors responsible for the reduced ATZ removal efficiency in real water matrices, while elevated TDS and conductivity further contribute to inhibition in saline or highly mineralized waters. Despite these inhibitory factors, the BC/PI system exhibited notable resilience when tested with real water samples, highlighting its potential applicability for tertiary treatment processes in real wastewater management. However, to enhance the performance of the BC/PI system in complex real water environments, it is essential to apply appropriate pre-treatment methods (e.g., coagulation, flocculation, filtration, or adsorption) or implement process optimization strategies (e.g., increasing oxidant/catalyst dosage, extending contact time, or employing staged treatment).

Figure 11.

(a) ATZ degradation ratios utilizing the BC/PI system with different water matrices and (b) ATZ degradation ratios using the BC/PI system at different HA acid concentrations (Conditions: pH = 7, [ATZ]o = 7.3 mg/L, T = 25 ± 0.5 °C, [BC]o = 0.55 g/L, and [PI]o = 2.7 mM).

Coexisting water components such as NOM, inorganic anions, and inorganic cations can inhibit the catalytic breakdown of organic pollutants in natural water bodies [81,82]. Therefore, the effects of representative substances frequently present in real aquatic environments on the oxidative degradation of ATZ were investigated. Small amounts of the tested substances according to the examined concentration were introduced into the reaction solution before initiating the degradation process. HA, representing NOM, was tested at 1, 5, and 10 mg/L doses. The tested inorganic anions, including Cl−, SO42−, NO3−, CO32−, HCO3−, HPO42−, and H2PO42− ions, were examined at concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 mM. Further, the effects of common cations, including Na+, K+, Mg2+, Cu2+, and Fe2+ ions, were assessed at a concentration of 10 mM.

Figure 11b and Figure S18 explain the effect of HA on ATZ degradation efficiency and kinetic rate constants in the BC/PI system, respectively. The addition of a small concentration of HA (1 mg/L) reduced the ATZ removal efficiency to 87.09%. This represents a decrease of approximately 12% compared to the control (sample without additions), which achieved a removal efficiency of 99.35%. At an increased HA concentration of 5 mg/L, ATZ removal efficiency declined further to 82.47%, showing an additional 5% reduction. At 10 mg/L HA, a negligible decrease (<1%) was observed, resulting in an ATZ removal efficiency of 81.75%. The increase in HA concentration to 5 mg/L and 10 mg/L did not adversely decrease the degradation efficiency due to the saturation of the biochar’s surface by HA at specific concentration of HA. Thus, adding higher concentrations did not show significant inhibition confirming that the inhibition in the case of HA was mainly due to the catalyst surface interaction with HA. The adsorption of hydroxyl and carboxyl groups from HA onto the BC surface could block its’ reactive locations, diminishing ATZ removal efficiency [26,83]. Additionally, the competition between ATZ and HA for ROS consumption might slightly inhibit the degradation efficiency [3,84]. The pseudo-first-order rate constants were 0.0335 (R2 = 0.9929) min−1, 0.0293 (R2 = 0.9929) min−1, and 0.0291 (R2 = 0.9914) min−1 for 1, 5, and 10 mg HA/L, respectively, compared to 0.0601 (R2 = 0.9462) min−1 in the control. Yang et al. [19] obtained similar results using nitrogen and magnesium codoped biochar to degrade bensulfuron methyl herbicide in a PI activation system.

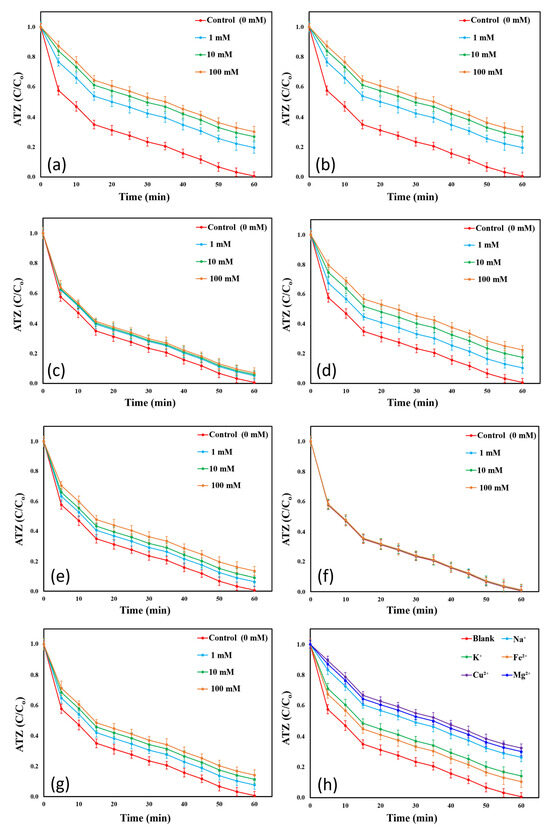

The impact of varying concentrations of inorganic ions on ATZ degradation in the BC/PI system is illustrated in Figure 12, while kinetic rate constants are presented in Figure S20. A summary of ATZ degradation ratios and K values at different concentrations of the tested inorganic anions is shown in Table S7. The strong inhibitory effect of NO3− on ATZ degradation was evident, with ATZ removal efficiency decreasing to 89.58% at a NO3− concentration of 1 mM and continuing to decline as NO3− concentration increased. A similar trend was reported in a study by Chen et al. [14], who utilized N-doped carbon nanotubes encapsulating cobalt as a PI activator for the removal of tetracycline from aqueous solutions. Although SO42− and H2PO4− anions exhibited a significant inhibitory effect on the system, ATZ removal efficiency remained above 85% even at high concentrations (100 mM). Xu et al. [24] reported a similar inhibitory effect of H2PO4− (5 mM) on the degradation of acid orange 7 dye in a visible light/PI-activated system. Conversely, Eslami et al. [21] observed a negligible SO42− inhibition in para-nitrophenol removal using a simultaneous UV and ultrasound system for PI activation.

Figure 12.

Impacts of various present inorganic ions on ATZ removal in the BC-catalyzed PI system: (a) HCO3−, (b) CO32−, (c) Cl−, (d) NO3−, (e) SO42−, (f) HPO42−, (g) H2PO4−, and (h) different cations at 10 mM (Conditions: pH = 7, [ATZ]o = 7.3 mg/L, T = 25 ± 0.5 °C, [BC]o = 0.55 g/L, and [PI]o = 2.7 mM).

The BC/PI system demonstrated strong adaptability to Cl− and HPO42−. At a concentration of 1 mM Cl−, the ATZ removal ratio declined by only 4.5%. Increasing the Cl− concentration to 10 and 100 mM resulted in minimal further decreases in ATZ degradation. Xu et al. [24] noted a slight inhibitory effect of Cl− at a concentration of 5 mM on the degradation of azo dye, in a PI-activated system. ATZ removal ratios decreased by only 0.7% to an HPO42− concentration of 100 mM, making it the anion with the lowest inhibitory effect on ATZ degradation in the BC/PI system. Similarly, Wang et al. [17] reported an insignificant effect of HPO42− on sulfisoxazole degradation in a PI-based process. Bicarbonate ions exhibited the highest inhibition effect on ATZ removal in the BC/PI system. Upon adding HCO3−, the ATZ degradation efficiency decreased to 74.34%, 67.59%, and 62.32% at HCO3− concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 mM, respectively, with corresponding kinetic constants of 0.0233 (R2 = 0.9928) min−1, 0.0192 (R2 = 0.9955) min−1, and 0.0162 (R2 = 0.9973) min−1. Xiong et al. [10] reported that, among various anions tested, HCO3− exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect on the degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride, in a CuFeS2/PI system. The inhibition effect of 100 mM CO32− resulted in an ATZ degradation ratio of 69.77% and a K value of 0.0204 (R2 = 0.9946) min−1. These findings align with previous studies by Elmitwalli et al. [18] and Xiong et al. [10]. The observed decline in ATZ removal efficiency after the addition of various inorganic components can result from several contributing factors. Adsorption of inorganic compounds on the catalyst surface can form an inorganic layer that reduces or blocks active sites. This blockage impedes the diffusion of PI and ATZ, diminishing its removal efficiency [19,85]. Additionally, inorganic ions might compete with ATZ for the generated ROS, thus reducing the ATZ degradation percentage [86,87]. Further, HCO3− introduction into the reaction solution increased the pH, which is less favorable in the BC/PI system because it promotes the formation of less ROS, which reduces the system’s overall efficiency [20,58]. Furthermore, certain inorganic anions, including Cl−, CO32−, HCO3−, and NO3−, exhibit quenching effects on some of the generated ROS, leading to the formation of radicals with lower oxidation potential. These low-reactivity radicals can partially deplete the ROS, thereby reducing the ATZ degradation [18,81]. Chloride ions can react with OH• and IO3•, forming less reactive chlorine species such as OHCl−, Cl•, and Cl2• −, as shown in Equations (16)–(20) [65,66]. Hydroxyl radicals may be scavenged by NO3−, resulting in the formation of nitrate radicals (NO3•) with a lower oxidation potential, as indicated in Equation (21) [88,89]. Bicarbonate ions are potent scavengers of OH• and IO3•. Their reaction with these species results in the formation of carbonate radicals (CO3• −), which exhibit a substantially lower oxidation potential, as illustrated in Equations (22) and (23) [28,90]. Similarly, CO32− can react with IO3• to form CO3• −, as shown in Equation (24) [91]. In addition, CO32− can quench OH•, resulting in the release of carbon dioxide (CO2), as illustrated in Equations (25) and (26) [92,93]. Notably, the negligible inhibitory impact of certain coexisting inorganic ions on the oxidative performance of the BC/PI system suggests that these ions were either easily oxidized by the BC/PI system or did not substantially interfere with the activity of the primary reactive species [17,89].