Abstract

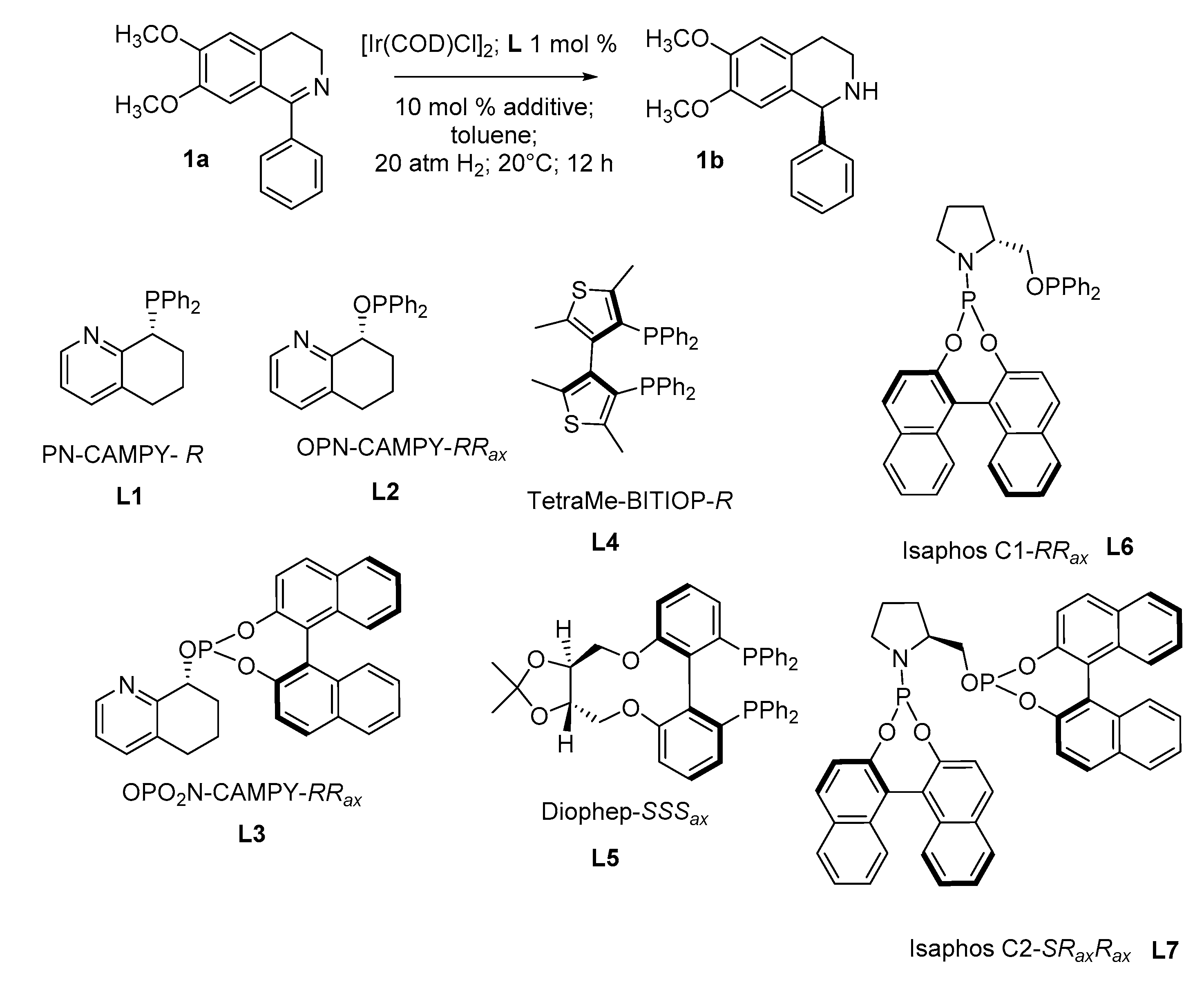

Starting from the chiral 5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinolin-8-ol core, a series of amino-phosphorus-based ligands was realized. The so-obtained amino-phosphine ligand (L1), amino-phosphinite (L2) and amino-phosphite (L3) were evaluated in iridium complexes together with the heterobiaryl diphosphines tetraMe-BITIOP (L4), Diophep (L5) and L6 and L7 ligands, characterized by mixed chirality. Their catalytic performance in the asymmetric hydrogenation (AH) of the model substrate 6,7-dimethoxy-1-phenyl-3,4-dihydroisoquinoline 1a led us to identify Ir-L4 and Ir-L5 catalysts as the most effective. The application of these catalytic systems to a library of differently substituted 1-aryl-3,4-dihydroisoquinolines afforded the corresponding products with variable enantioselective levels. The 4-nitrophenyl derivative 3b was obtained in a complete conversion and with an excellent 94% e.e. using Ir-L4, and a good 76% e.e. was achieved in the reduction of 2-nitrophenyl derivative 6a using Ir-L5.

1. Introduction

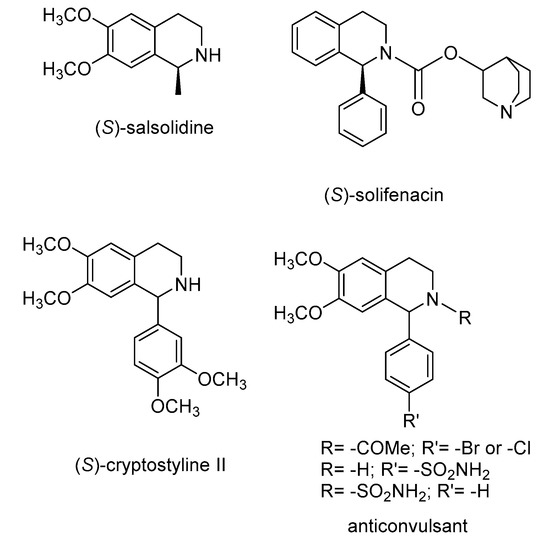

Many pharmaceutically active compounds owe their physiological activity to the presence of an aminic group in their structure. In particular, 1,2,3,4–tetrahydroquinolines and their analogs are very important building blocks for the synthesis of biologically active compounds [1,2,3] such as salsolidine [4,5,6,7] and carnegine [8], solifenacin [9], cryptostyline [10], complex alkaloids [11,12,13,14] and new derivatives active as anti-HIV agents [15] and as anticonvulsants (as an inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase [16] or as a non-competitive antagonist via interaction with the glutamate ionotropic AMPA receptor complex) [17] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representative bioactive compounds based on tetrahydroquinolines

The traditional organic methods for the synthesis of tetrahydroquinoline are based on condensation, the cyclization/reduction sequence and intramolecular nucleophilic addition [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Many efforts have been made to improve the synthetic approach via catalytic methods [7,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Considering the convenience in terms of efficiency and atom economy, asymmetric hydrogenation (AH) of prochiral imines, using phosphine-based metal complexes as catalysts, was evinced as the most practical application. It is well known that the steric hindrance of the ligands plays an important role in the asymmetric reduction of this substrate, and matching the hindrance of both catalyst and substrate could enhance the performance of the asymmetric reduction. Among the very first works in the asymmetric hydrogenation of such a class of substrates [32,33], Zhang’s group [28] and Ratovelomanana-Vidal’s group [34,35] have made a breakthrough, setting up an innovative strategy for the reduction of dihydroisoquinolines. The atropoisomerism, stemming from a restricted rotation around aryl–aryl bonds, constitutes the structural feature accounting for the selectivity in many diphosphine ligands, both as binaphane-type ligands and as classic chiral ones [36,37]. On the contrary, the amino-monophosphine ligands bearing a 1,1′-bi-2-naphthol as an additional source of chirality have been less studied. In this work, we compared three different types of phosphine ligands bearing an atropoisomeric chirality in iridium (III) complexes for the reduction of substituted cyclic aromatic 1-aryl imines.

2. Results and Discussion

Atropoisomerism is a special characteristic that, based on the 1,1′-bi-2-naphthol moiety, furnishes one of the most common and efficient sources of chirality in the pool of phosphine ligands.

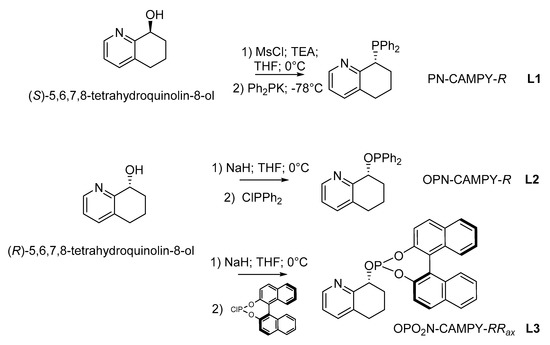

Based on our experience in the use of the chiral 8-amino-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinoline scaffold and its derivatives as ligands in transition metal complexes, and considering their employment as sources of chirality in organometallic catalysts for asymmetric reduction or for C–B bond formation reactions [38,39,40], we decided to focus our attention on the synthesis of three amino monophosphine ligands: amino-phosphine (L1), -phosphinite (L2) [41,42] and -phosphite (L3). For the synthesis of amino monophosphines, we started from the chiral 5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinolin-ol, the enantiomers of which were successfully separated through enzymatic DKR by Candida antarctica lipase B with high yield and purity [43]. The synthesis of the three different types of amino monophosphines proceeded as reported in Scheme 1. These ligands were synthesized with the aim of evaluating the importance of the atropoisomeric scaffold when starting from an amino-phosphine in order to afford ligand L3, in which the 1,1′-bi-2-naphthol moiety resulted in an additional source of chirality or/and of additional steric hindrance.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 8-(diphenylphosphanyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinoline, PN-CAMPY-R L1, (R)-8-((diphenylphosphanyl)oxy)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinoline, OPN-CAMPY-R L2 and (8R)-8-(((4R)-dinaphtho[2,1-d:1′,2′-f][1,3,2]dioxaphosphepin-4-yl)oxy)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinoline, OPO2N-CAMPY-RRax L3.

In the case of the monophosphine L1, the synthesis proceeded without racemization at the chiral center at position 8 of the tetrahydroquinoline, as evinced by chiral HPLC analysis (see SI). These monophosphines were used in comparison with other atropoisomeric phosphines known from the literature, in each of which atropoisomerism assumed peculiar features: in L4 [44,45] and L5 [46], the heterobiaryl moiety afforded the core of the diphosphines, introducing an axial chirality element comparable to the one arising from a 1,1′-bi-2-naphthol, although with a different steric hindrance. Moreover, L5 provided mixed stereogenic elements similar to L6 and L7 [47] in which the ligands comprise one stereogenic sp3 carbon atom backbone and the stereogenic axis of the biaryl moiety (Table 1).

Table 1.

Screening of different iridium complexes bearing L1–7.

The catalytic investigation was applied to the asymmetric hydrogenation of a series of synthesized cyclic aromatic 1-aryl imines under different reaction conditions, employing Ir-precatalysts generated in situ. For a preliminary screening, the commercially available 6,7-dimethoxy-1-phenyl-3,4-dihydroisoquinoline 1a was used as a model substrate in order to set up the reaction.

Among the variables of the conditions taken into consideration, the ones able to impact the outcome of the reaction included the use of different types of additives (1,3-dichloro-5,5-dimethylhydantoin, DCDMH [48], FeCl3, N-bromosuccinimide, NBS, N-chlorosuccinimide [32] or H3PO4 [9]) and of the solvent employed (THF, toluene, CH2Cl2) [49] (see SI, Table S1; data refer to substrate 1a). In the reactions in which L1, L2, L3 and L7 were used as ligands, the presence of an additive proved mandatory (Table 1, entries 1, 3, 5 and 17). From the obtained results, the optimized protocol for the AH reaction comprised a 100/1 substrate/catalyst ratio in toluene under 20 atm of molecular hydrogen in the presence of 10% molar of additive at 20°C for 12 h. Neither the increase in temperature nor a higher hydrogen pressure allowed significant variations to be obtained in terms of enantioselectivity.

The obtained data underlined that the best results in terms of conversion and enantioselectivity were achieved by using NBS as an additive for all ligands (Table 1, entries 2, 4, 6, 9, 11, 13, 16 and 18). Regarding the phosphorous ligands, the amino-monophosphines L1-L3 proved less active, and only modest enantiomeric excesses accompanied the reaction (20–39% e.e., Table 1, entries 2, 4 and 6), although the addition of the 1,1′-bi-2-naphtol moiety in the ligand slightly increased the enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 6). The same results were obtained in the presence of ligands L6 and L7, in which the mixed types of chirality (sp3 and axial) did not match (Table 1, entries 16 and 18). The best results were obtained by the classical atropoisomeric diphosphines L4 and L5 (Table 1, entries 9 and 13). In particular, in the presence of tetraMe-BITIOP as the ligand, good enantioselectivity was achieved with either NBS or DCDMH as the additive, although the conversion was completed only in the presence of NBS within 12 h (Table 1, entry 7 vs. entry 9). An increase in the substrate/catalyst ratio to 250/1 did not affect the enantioselectivity of the reaction, with only a minimum erosion in terms of conversion within the settled reaction time (12 h) (Table 1, entry 11).

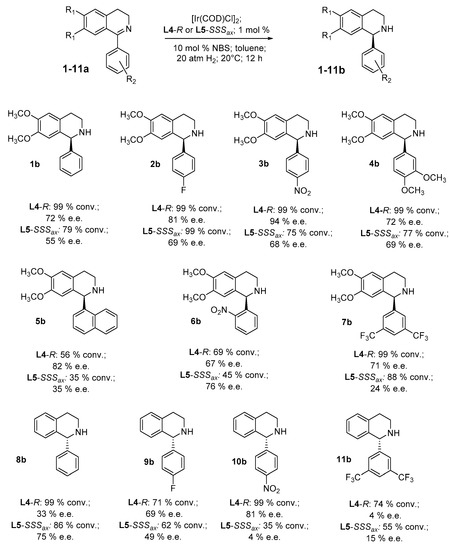

The synthesis of differently substituted derivatives of the standard substrate 1a was accomplished following the well-known Bischler–Napieralski cyclodehydration [50]. All the obtained products were fully characterized by NMR and MS analysis results in accordance with the data reported in the literature, with the exception of 1-(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3,4-dihydroisoquinoline, 11a, here reported for the first time to the best of our knowledge. Considering that the best performances were obtained using atropoisomeric diphosphines L4 and L5 in situ coordinated with the iridium(III) metal center (see Table S1 in SI for comparison), the asymmetric hydrogenation of the substrates reported below was carried out under the following optimized reaction conditions established for the standard substrate 1a: substrate/catalyst ratio of 100/1 (final substrate concentration of 10 mM) in toluene in the presence of 10% molar of NBS as an additive under 20 atm of hydrogen pressure at 20 °C for 12 h. This allowed a comparison of the reactivity of the catalytic systems to be made relative to the structural and electronic differences of the substrates.

As evinced by the data reported in Figure 2, for all the 1-aryl imines, the best results in terms of enantioselectivity and conversion were afforded by using the L4 ligand, providing an e.e. of up to 94% along with 99% conversion for the substrate 3a. The only exceptions were obtained in the reduction of 1-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline, 8a, for which L5 raised the enantiomeric excess to 75% with a good conversion of 86%, and in the reduction of the substrate 6a, for which a 76% e.e. was reached, although with a modest conversion of 45%. Indeed, the reduction of the substrates 8a-11a, characterized by the absence of the two methoxy groups on the quinoline ring, confirmed the pivotal role of the p-NO2 group in furnishing enantiodiscrimination in the reaction when Ir-L4 was used as the catalyst, allowing it to obtain 10b with 81% e.e. The differences in both enantioselectivity and conversion rate between the two diphosphines could be due to the basicity and, consequently, to the more electron-rich properties of L4 compared with L5 and, conversely, to the steric hindrance of L5, which is greater than that of L4.

Figure 2.

Asymmetric hydrogenation of different 1-aryl imines using L4 and L5 as ligands.

3. Experimental

General:1H-, 13C- and 31P-NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 or C6D6 on Bruker DRX Avance 400 and 300 MHz equipped with a non-reverse probe. Chemical shifts (in ppm) were referenced to the residual solvent proton/phosphorous peak. MS analyses were performed by using a Thermo Finnigan (MA, USA) LCQ Advantage system MS spectrometer with an electrospray ionization source and an ‘Ion Trap’ mass analyzer. The MS spectra were obtained by direct infusion of a sample solution in MeOH under ionization, ESI positive. Catalytic reactions were monitored by HPLC analysis with Merck-Hitachi L-7100 equipped with Detector UV6000LP and a chiral column (Chiralcel OD-H, Chiralpak AD, Lux Cellulose-2 or Lux Amylose-2).

3.1. General Procedure for Synthesis of Substrates

The synthesis of substrates was conducted as reported in the literature. To a solution of 2-arylethylamine (1.0 eq.) and triethylamine (1.5 eq.) in CH2Cl2 (40 mL) at 0 °C, carbonyl chloride (1.0 eq.) was slowly added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight, and then it was concentrated in vacuo. EtOAc (30 mL) was added, and the solution was washed with saturated NH4Cl solution (30 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL), and the combined organic layers were washed with brine (50 mL) and dried with anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated, and the residue was used without further purification. To a solution of N-acyl-2-arylethylamine (1.0 eq.) and 2-chloropyridine (1.2 eq.) in CH2Cl2 (25 mL) cooled at −78 °C, trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride (1.1 eq.) was added dropwise. Then, the mixture was slowly warmed to room temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction was quenched with saturated NaHCO3 solution and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine and dried with anhydrous Na2SO4. After that, the solvent was reduced in vacuo, and the obtained product was purified by flash chromatography (yield: 50–85%). All the obtained substrates were characterized, and the analytical results matched those reported in the literature [25,50,51,52,53,54].

1-(3,5-Bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3,4-dihydroisoquinoline, (11a): pale yellow oil, yield 53%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.12 (s, 2H), 7.97 (s, 1H), 7.44 (dt, J = 7.5 Hz J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.27 (m, 2H), 7.15 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 3.94–3.89 (m, 2H), 2.87–82 (m, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 164.9, 141.0, 138.8, 131.6 (q, 2JCF = 33 Hz, 2C), 131.4, 129.0 (q, 3JCF = 3.0 Hz, 2C), 127.9, 127.7, 127.0, 126.9, 126.8 (q, 1JCF = 273 Hz, 2C), 123.0 (q, 3JCF = 3.8 Hz), 47.9, 26.0 ppm. FTIR (NaCl) ν = 3072.04, 2941.10, 1624.11, 1609.56, 1389.17, 1278.13, 1183.71, 1128.18, 890.92, 745.80 cm−1; MS (ESI) for C17H11F6N: m/z 344.01 [M+H]+.

3.2. Synthesis of (R)-8-(Diphenylphosphanyl)-5,6,7,8-Tetrahydroquinoline, L1

The chiral 5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinoline-8-ol was obtained as previously reported with a yield of 89% for the (R)-enantiomer (99% e.e.) and 87% for the (S)-enantiomer (96% e.e.) [43]. To a solution of (S)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinoline-8-ol (1 mmol) in 5 mL of anhydrous THF at 0 °C, TEA (2.5 eq.) was added. Methanesulfonyl chloride (1.5 eq.) was added dropwise, and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min. The temperature was decreased to −78 °C, and potassium diphenylphosphide solution (0.5 M) in THF (1.7 eq.) was added within 15 min. The mixture was stirred for 6 h, and the temperature was warmed to room temperature. At the end of the reaction, 5 mL of diethyl ether and HCl (2M) was added until the solution reached an acid pH. The organic phase was extracted with 3 × 5 mL of diethyl ether and washed with a saturated solution of Na2CO3 until it reached a basic pH. The aqueous phase was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 5 mL). Combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, and the solvent was evaporated. The obtained product did not need further purification. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ: 8.23 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.53–7.21 (m, 11H), 6.99–6.95 (m, 1H), 3.93–3.88 (m, 1H), 2.75 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.08–1.98 (m, 1H), 1.90–1.77 (m, 2H), 1.73–1.62 (m, 1H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 158.6, 147.3, 137.0, 135.1, 134.8, 134.2 (2C), 133.9 (2C), 129.4, 129.0 (2C), 128.9 (2C), 128.4 (2C), 121.6, 41.7, 29.1, 26.8, 22.2 ppm; 31P-NMR (CDCl3, 160 MHz): δ 2.76 ppm; MS (ESI) for C21H20NP: m/z 318.23 [M+H]+.

3.3. Synthesis of (R)-8-((Diphenylphosphanyl)oxy)-5,6,7,8-Tetrahydroquinoline and (8R)-8-(((4R)-Dinaphtho[2,1-d:1′,2′-f][1,3,2]Dioxaphosphepin-4-yl)oxy)-5,6,7,8-Tetrahydroquinoline, L2 and L3

The chiral 5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinolin-8-ol and (R)-(+)-1,1′-binaphthyl-2,2′-diylphosphite chloride were obtained as previously reported. To a solution of NaH (1.1 eq.) in 5 mL of anhydrous THF at 0°C was added (S)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinolin-8-ol (1 mmol). The suspension was stirred for 30 min, and chlorodiphenylphosphine or (R)-(+)-1.1′-binaphthyl-2,2′-diylphosphite chloride (1.1 eq.) was added. The mixture was then stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Then, 10 mL of diisopropyl ether was added, and the formed precipitate, containing the inorganic salts, was filtered off. The solvent was evaporated, and the obtained white solid did not need further purification.

L2: 1H-NMR (C6D6, 400 MHz) δ: 8.30 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.78–7.63 (m, 2H), 7.50–7.10 (m, 10H), 4.74 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 2.76–2.65 (m, 2H), 2.16–1.68 (m, 4H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 152.6, 146.3, 137.0, 133.4, 132.8, 134.6, 131.8 (4C), 131.2 (2C), 128.7 (2C), 127.8 (2C), 121.9, 43.2, 28.4, 23.8, 20.7 ppm; 31P-NMR (C6D6, 160 MHz): δ 111.4 ppm; MS (ESI) for C21H20NOP m/z 334.43 [M+H]+.

L3: 1H-NMR (C6D6, 400 MHz) δ: 7.96–7.02 (m, 14H), 6.84 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.92 (m, 1H), 2.72–2.61 (m, 3H), 2.28–2.23 (m, 1H), 1.92–1.89 (m, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.0, 150.1 (2C), 145.3, 137.6, 134.6, 134.1, 133.7, 132.8, 131.8, 128.8 (2C), 128.4 (2C), 128.0 (2C), 127.7 (2C), 124.1 (2C), 123.2 (2C), 121.7, 117.9 (2C), 43.3, 28.8, 24.1, 20.8 ppm; 31P-NMR (C6D6, 160 MHz): δ 145.3 ppm; MS (ESI) for C29H22NO3P: m/z 464.57 [M+H]+.

3.4. General Procedure for Asymmetric Hydrogenation

[Ir(COD)Cl]2 (0.5 eq.) was added to a solution of phosphine (1 eq.) in 5 mL of solvent, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The additive (10 eq.) was added and, after stirring for an additional 15 min, the imine (100 eq.) was added to the reaction mixture. The solution was transferred to a stainless-steel autoclave (50 mL) with a cannula. The autoclave, equipped with temperature control and magnetic stirrer, was purged five times with hydrogen and then pressurized at 20 atm, and the temperature was set to 20 °C. At the end, the autoclave was vented, and the mixture was analyzed by HPLC equipped with a chiral column (for analytical conditions, see below).

3.5. Analytical Conditions

The products were analyzed by 1H NMR to determine the molar conversion, whereas the enantiomeric excess was evaluated by HPLC analysis, and the absolute configuration was assigned by comparison with literature references [25,55].

6,7-Dimethoxy-1-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline1b [25]: R-isomer: 12.1 min (min); S-isomer: 17.3 min (maj); column: Chiralcel OD-H, eluent: 2-propanol/hexane = 30/70 (0.01% DEA), flow = 0.7 mL/min, λ = 220 nm.

1-(4-Fluorophenyl)-6,7-dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline2b [25]: R-isomer: 21.0 min (min); S-isomer: 23.9 min (maj); column: Chiralpak AD, eluent: 2-propanol/hexane = 10/90, flow = 0.8 mL/min, λ = 220 nm.

6,7-Dimethoxy-1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline3b [54]: R-isomer: 25.7 min (min); S-isomer: 32.5 min (maj); column: Chiralcel OD-H, eluent: 2-propanol/hexane = 30/70 (0.01% DEA), flow = 0.7 mL/min, λ = 285 nm.

1-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-6,7-dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline4b [25]: R-isomer: 23.7 min (min); S-isomer: 33.0 min (maj); column: Chiralcel OD-H, eluent: 2-propanol/hexane = 30/70 (0.01% DEA), flow = 0.7 mL/min, λ = 285 nm.

6,7-Dimethoxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline5b [35]: 1 isomer: 14.7 min (min); 2 isomer: 16.4 min (maj); column: Chiralcel OD-H, eluent: 2-propanol/hexane = 30/70 (0.01% DEA), flow = 0.7 mL/min, λ = 285 nm.

6,7-Dimethoxy-1-(2-nitrophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline6b [24]: 1 isomer: 8.6 min (min); 2 isomer: 15.0 min (maj); column: Chiralcel OD-H, eluent: 2-propanol/hexane = 30/70 (0.01% DEA), flow = 0.7 mL/min, λ = 240 nm.

1-(3,5-Bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-6,7-dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline7b [56]: 1 isomer: 7.5 min (maj); 2 isomer: 8.5 min (min); column: Lux Amilose-2, eluent: 2-propanol/hexane = 10/90 (0.01% DEA), flow = 0.8 mL/min, λ = 220 nm.

1-Phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline8b [25]: S-isomer: 13.1 (min); R-isomer: 15.4 (maj); column: Chiralpak AD, eluent: 2-propanol/hexane = 4/96, flow = 0.8 mL/min, λ = 240 nm.

1-(4-Fluorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline9b [25]: S-isomer: 5.5 (min); R-isomer: 7.1 (maj); column: Lux Amylose-2, eluent: 2-propanol/hexane = 10/90, flow = 1.0 mL/min, λ = 220 nm.

1-(4-Nitrophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline10b [26]: S-isomer: 15.9 (min); R-isomer: 20.9 (maj); column: Lux Amylose-2, eluent: 2-propanol/hexane = 10/90 (0.01% DEA), fl ow = 0.8 mL/min, λ = 254 nm.

1-(3,5-Bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (11b): yellow solid, yield 61 %; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.84 (s, 1H), 7.80 (s, 2H), 7.36–7.32 (m, 1H), 7.20–7.21 (m, 2H), 7.12–07 (m, 1H), 5.25 (s, 1H), 3.20–3.13 (m, 2H), 2.91–2.82 (m, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 147.9, 136.8, 135.9, 132.0 (q, 2JCF = 33 Hz, 2C), 129.9, 129.6 (q, 3JCF = 3.3 Hz, 2C), 128.1, 127.4, 126.4, 123.3 (q, 1JCF = 273 Hz, 2C), 121.9 (q, 3JCF = 3.8 Hz), 61.8, 42.7, 29.9 ppm. FTIR (NaCl) ν = 3035.13, 2901.08, 1571.24, 1350.12, 1228.89, 1165.04, 1153.73, 873.20, 778.63 cm−1; MS (ESI) for C17H13F6N: m/z 346.21 [M+H]+. HPLC: 1 isomer: 8.2(min); 2 isomer: 12.0 (maj); column: Lux Cellulose-2, eluent: 2-propanol/hexane = 5/110, flow = 0.6 mL/min, λ = 220 nm.

4. Conclusions

Different types of chiral phosphines serving as a source of chirality in an atropoisomeric moiety due to the presence of axial biaryl asymmetry were evaluated in the reduction of a standard cyclic imine, 6,7-dimethoxy-1-phenyl-3,4-dihydroisoquinoline 1a. By this preliminary screening, the classical atropoisomeric diphosphines, L4 and L5, proved the most effective ligands in iridium complexes for the asymmetric hydrogenation of this substrate, while the amino-monophosphines L1, L2 and L3 were less stereoselective as ligands despite the presence of the additional 1,1′-bi-2-naphthol moiety. The ligands L6 and L7, comprising both the stereogenic sp3 carbon atom backbone and the stereogenic axis of the biaryl moiety, resulted in poor enantioselectivity. With the optimal reaction conditions in hand, we were able to extend the scope of the reaction to a series of 1-aryl cyclic imines, different from an electronic point of view for the presence of electron-withdrawing or electron-donor groups on the 1-phenyl substituent. An excellent 94% e.e. was achieved in the AH of the substrate 3a using the Ir-L4 complex, with a complete conversion for substrate 7a, although with a lower but still good 71% e.e. A remarkable point is the 82% e.e. reached in the reduction of the steric-hindered imine 5a. The Ir-catalytic system, [Ir(COD)Cl]2 and the L5 ligand, afforded the best results in the AH of the 1-(2-nitro)phenyl-substituted substrate 6a with a 76% e.e. and in the AH of the simple but demanding substrate 8a, affording the product with a good e.e. of 75% and with 86% conversion.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4344/10/8/914/s1, Table S1: Preliminary screening with L1-L7.

Author Contributions

These authors contributed equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Scott, J.D.; Williams, R.M. Chemistry and Biology of the Tetrahydroisoquinoline Antitumor Antibiotics. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 1669–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, K.; Saitoh, T.; Horiguchi, Y.; Utsunomiya, I.; Taguchi, K. Synthesis and Neurotoxicity of Tetrahydroisoquinoline Derivatives for Studying Parkinson’s Disease. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 1355–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.R.; Safo, M.K.; Abraham, D.J. Identification of a series of tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives as potential therapeutic agents for breast cancer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 2581–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinto, T.; Schwizer, F.; Zimbron, J.M.; Morina, A.; Köhler, V.; Ward, T.R. Expanding the Chemical Diversity in Artificial Imine Reductases Based on the Biotin-Streptavidin Technology. ChemCatChem 2014, 6, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyori, R.; Ohta, M.; Hsiao, Y.; Kitamura, M.; Ohta, T.; Takaya, H. Asymmetric synthesis of isoquinoline alkaloids by homogeneous catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 7117–7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwizer, F.; Okamoto, Y.; Heinisch, T.; Gu, Y.; Pellizzoni, M.M.; Lebrun, V.; Reuter, R.; Köhler, V.; Lewis, J.C.; Ward, T.R. Artificial Metalloenzymes: Reaction Scope and Optimization Strategies. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 142–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchetti, G.; Rimoldi, I. 8-Amino-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinoline in iridium(iii) biotinylated Cp* complex as artificial imine reductase. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 18773–18776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, S.G.; Bloem, P.; Chapman, S.L.; Dixon, C.E.; Griffith, R. Chiral sulfur compounds. 9. Stereochemistry of the intermolecular and intramolecular conjugate additions of amines and anions to chiral (E)- and (Z)-vinyl sulfoxides. Total syntheses of (R)-(+)-carnegine and (+)- and (-)-sedamine. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ružič, M.; Pečavar, A.; Prudič, D.; Kralj, D.; Scriban, C.; Zanotti-Gerosa, A. The Development of an Asymmetric Hydrogenation Process for the Preparation of Solifenacin. Org. Process Res. Dev 2012, 16, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Xu, Z.; Ding, W.; Liu, S.; Shi, X.; Lu, X. Efficient and Practical Syntheses of Enantiomerically Pure (S)-(−)-Norcryptostyline I, (S)-(−)-Norcryptostyline II, (R)-(+)-Salsolidine and (S)-(−)-Norlaudanosine via a Resolution-Racemization Method. Chin. J. Chem. 2014, 32, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhurakulov, S.N.; Babkin, V.A.; Chernyak, E.I.; Morozov, S.V.; Grigor’ev, I.A.; Levkovich, M.G.; Vinogradova, V.I. Aminomethylation of 1-Aryl-6,7-Dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroisoquinolines by Dihydroquercetin. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2015, 51, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guranova, N.I.; Varlamov, A.V.; Novikov, R.A.; Aksenov, A.V.; Borisova, T.N.; Sorokina, E.A.; Voskressensky, L.G. Reaction of benzyne with 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolines as an access to 1H-3-benzazepines. Mendeleev Commun. 2018, 28, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrzanowska, M.; Rozwadowska, M.D. Asymmetric Synthesis of Isoquinoline Alkaloids. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3341–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, K.W. β-Phenylethylamines and the isoquinoline alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006, 23, 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, P.; Huang, N.; Jiang, Z.-Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Y.T.; Chen, J.J.; Zhang, X.M.; Ma, Y.B. 1-Aryl-tetrahydroisoquinoline analogs as active anti-HIV agents in vitro. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 2475–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, E.; Buemi, M.R.; De Luca, L.; Ferro, S.; Monforte, A.M.; Supuran, C.T.; Vullo, D.; De Sarro, G.; Russo, E.; Gitto, R. In Vivo Evaluation of Selective Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors as Potential Anticonvulsant Agents. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 1812–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitto, R.; Ferro, S.; Agnello, S.; De Luca, L.; De Sarro, G.; Russo, E.; Vullo, D.; Supuran, C.T.; Chimirri, A. Synthesis and evaluation of pharmacological profile of 1-aryl-6,7-dimethoxy-3,4-dihydroisoquinoline-2(1H)-sulfonamides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 3659–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.N.; Singh, P.; Kaur, M.; Sharma, E. Intermolecular Nucleophilic Addition of N-Diaminophosphinoyl-Protected α-Carbanions Derived from Secondary Amines to Arynes: Synthesis of 1-Aryl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolines. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 2213–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesnot, T.; Gershater, M.C.; Ward, J.M.; Hailes, H.C. Phosphate mediated biomimetic synthesis of tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 3242–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Eynden, M.J.; Kunchithapatham, K.; Stambuli, J.P. Calcium-Promoted Pictet-Spengler Reactions of Ketones and Aldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 8542–8549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Eynden, M.J.; Stambuli, J.P. Calcium-Catalyzed Pictet−Spengler Reactions. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5289–5291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doi, S.; Shirai, N.; Sato, Y. Abnormal products in the Bischler–Napieralski isoquinoline synthesis. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1997, 15, 2217–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Adili, A.; Seidel, D. Redox-Annulations of Cyclic Amines with Electron-Deficient o-Tolualdehydes. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 1845–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedejs, E.; Trapencieris, P.; Suna, E. Substituted Isoquinolines by Noyori Transfer Hydrogenation: Enantioselective Synthesis of Chiral Diamines Containing an Aniline Subunit. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 6724–6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, H.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, X.; Wei, Z.; Yao, L.; Zhou, G.; Wang, P.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, S. Josiphos-Type Binaphane Ligands for Iridium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Hydrogenation of 1-Aryl-Substituted Dihydroisoquinolines. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 8641–8645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Václavíková, B.; Budinská, A.; Václavík, J.; Matoušek, V.; Kuzma, M.; Červený, L. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of 1-Aryl-3,4-Dihydroisoquinolines Using a Cp*Ir(TsDPEN) Complex. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 5131–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.M.; Wang, Y.Q.; Han, X.W.; Zhou, Y.G. Asymmetric hydrogenation of quinolines and isoquinolines activated by chloroformates. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2006, 118, 2318–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Li, W.; Zhang, X. A Highly Efficient and Enantioselective Access to Tetrahydroisoquinoline Alkaloids: Asymmetric Hydrogenation with an Iridium Catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10679–10681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Ye, Z.S.; Cao, L.L.; Guo, R.N.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Y.G. Enantioselective Iridium-Catalyzed Hydrogenation of 3,4-Disubstituted Isoquinolines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 8286–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Tan, R.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, X. Strong Bronsted acid promoted asymmetric hydrogenation of isoquinolines and quinolines catalyzed by a Rh-thiourea chiral phosphine complex via anion binding. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 3047–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, R.; Togni, A. P-Trifluoromethyl ligands derived from Josiphos in the Ir-catalysed hydrogenation of 3,4-dihydroisoquinoline hydrochlorides. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 19566–19575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, M.; Shi, L.; Zhou, Y. Dual Stereocontrol for Enantioselective Hydrogenation of Dihydroisoquinolines Induced by Tuning the Amount of N-Bromosuccinimide. Chin. J. Chem. 2018, 36, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Ji, Y.; Shi, L.; Sun, L.; Zhou, Y. A Method Catalyzed by Iridium and Used for Bidirectional Enantioselective Synthesis of Chiral Tetrahydroisoquinoline. CN107540606 A, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berhal, F.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ayad, T.; Ratovelomanana-Vidal, V. Enantioselective Synthesis of 1-Aryl-tetrahydroisoquinolines through Iridium Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3308–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Wu, Z.; Scalone, M.; Ayad, T.; Ratovelomanana-Vidal, V. Enantioselective Synthesis of 1-Aryl-Substituted Tetrahydroisoquinolines Through Ru-Catalyzed Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2015, 6503–6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusè, M.; Rimoldi, I.; Cesarotti, E.; Rampino, S.; Barone, V. On the relation between carbonyl stretching frequencies and the donor power of chelating diphosphines in nickel dicarbonyl complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 9028–9038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusè, M.; Rimoldi, I.; Facchetti, G.; Rampino, S.; Barone, V. Exploiting coordination geometry to selectively predict the σ-donor and π-acceptor abilities of ligands: A back-and-forth journey between electronic properties and spectroscopy. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2397–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimoldi, I.; Facchetti, G.; Cesarotti, E.; Pellizzoni, M.; Fuse, M.; Zerla, D. Enantioselective transfer hydrogenation of aryl ketones: Synthesis and 2D-NMR characterization of new 8-amino-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinoline Ru(II)-complexes. Curr. Org. Chem. 2012, 16, 2982–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, R.; Facchetti, G.; Christodoulou, M.S.; Fusè, M.; Meneghetti, F.; Rimoldi, I. Cascade Reaction by Chemo and Biocatalytic Approaches to Obtain Chiral Hydroxy Ketones and anti 1,3–Diols. ChemistryOpen 2018, 7, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchetti, G.; Ferri, N.; Lupo, M.G.; Giorgio, L.; Rimoldi, I. Monofunctional PtII Complexes Based on 8-Aminoquinoline: Synthesis and Pharmacological Characterization. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 2019, 3389–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, S.; Smidt, S.P.; Pfaltz, A. Iridium Catalysts with Bicyclic Pyridine–Phosphinite Ligands: Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Olefins and Furan Derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 5194–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.B.; Yu, C.B.; Zhou, Y.G. Synthesis of tunable phosphinite–pyridine ligands and their applications in asymmetric hydrogenation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 4733–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uenishi, J.; Hamada, M. Synthesis of Enantiomerically Pure 8-Substituted 5,6,7,8-Tetrahydroquinolines. Synthesis 2002, 2002, 0625–0630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benincori, T.; Brenna, E.; Sannicolò, F.; Trimarco, L.; Antognazza, P.; Cesarotti, E.; Demartin, F.; Pilati, T. New Class of Chiral Diphosphine Ligands for Highly Efficient Transition Metal-Catalyzed Stereoselective Reactions: The Bis(diphenylphosphino) Five-membered Biheteroaryls. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 6244–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchetti, G.; Cesarotti, E.; Pellizzoni, M.; Zerla, D.; Rimoldi, I. “In situ” Activation of Racemic RuII Complexes: Separation of trans and cis Species and Their Application in Asymmetric Reduction. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 2012, 4365–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarotti, E.; Abbiati, G.; Rossi, E.; Spalluto, P.; Rimoldi, I. DIOPHEP, a chiral diastereoisomeric bisphosphine ligand: Synthesis and applications in asymmetric hydrogenations. Tetrahedron 2008, 19, 1654–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarotti, E.; Araneo, S.; Rimoldi, I.; Tassi, S. Aminophosphonite-phosphite and aminophosphonite-phosphinite ligands with mixed chirality: Preparation and catalytic applications in asymmetric hydrogenation and hydroformylation. J. Mol. Catal. A 2003, 204-205, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchetti, G.; Bucci, R.; Fusè, M.; Rimoldi, I. Asymmetric Hydrogenation vs Transfer Hydrogenation in the Reduction of Cyclic Imines. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 8797–8800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, X.; Liu, R.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Jiang, R.; Nie, H.; Zhang, S. Josiphos-type binaphane ligands for the asymmetric Ir-catalyzed hydrogenation of acyclic aromatic N-aryl imines. Catal. Commun. 2020, 136, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, L.; Yang, W.; Weng, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y. A Method for Bischler–Napieralski-Type Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydroisoquinolines. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 2574–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Luo, S. Mechanistic Studies on Bioinspired Aerobic C–H Oxidation of Amines with an ortho-Quinone Catalyst. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 2542–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Yi, H.; Lei, A. Electrochemical Acceptorless Dehydrogenation of N-Heterocycles Utilizing TEMPO as Organo-Electrocatalyst. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 1192–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Trieu, T.H.; Li, F.L.; Zhu, X.L.; He, Y.G.; Fan, Q.Q.; Shi, X.X. Copper-Catalyzed Benign and Efficient Oxidation of Tetrahydroisoquinolines and Dihydroisoquinolines Using Air as a Clean Oxidant. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 8243–8252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucena-Serrano, C.; Lucena-Serrano, A.; Rivera, A.; López-Romero, J.M.; Valpuesta, M.; Díaz, A. Synthesis and dopaminergic activity of a series of new 1-aryl tetrahydroisoquinolines and 2-substituted 1-aryl-3-tetrahydrobenzazepines. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 80, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.W.; Ji, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Q.A.; Shi, L.; Zhou, Y.G. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Isoquinolines and Pyridines Using Hydrogen Halide Generated in Situ as Activator. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 4988–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hati, S.; Sen, S. Cerium Chloride Catalyzed, 2-Iodoxybenzoic Acid Mediated Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Multiple Heterocycles at Room Temperature. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 1277–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).