Abstract

How are allocation results affected by information that another anonymous participant intends to be more or less generous? We explore this experimentally via two participants facing the same allocation task with only one actually giving after possible adjustment of own generosity based on the other’s intended generosity. Participants successively face three game types, the ultimatum, yes-no and impunity game, or (between subjects) in the reverse order. Although only the impunity game appeals to intrinsic generosity, we confirm conditioning even when sanctioning is possible. Based on our data, we distinguish two major types of participants in all three games: one yielding to the weakest social influence and the other immune to it and offering much less. This is particularly interesting in the impunity game where other-regarding concerns are minimal.

1. Introduction

Generosity is an important aspect of human social interaction usually attributed to intrinsic motivation like impure or warm glow altruism (see e.g., Andreoni [1,2]). However generosity can be affected by social and strategic influence (e.g., via conformity seeking, reputation formation, etc. see Vesterlund [3] for a survey). Our aim is to shed new light on how others’ intentions can affect one’s own generosity when wanting to help.

To this end, we run an experiment in which participants are matched in pairs of allocator candidates who both state their generosity intention although only one is randomly selected as actual allocator and solely responsible for a needy participant. Before knowing the own actual role, each participant states her independent generosity intention and can adjust it via conditioning on information that the other’s generosity intention is larger or smaller. Will one allocator candidate condition her offer on an anonymous other’s intention when this is purely counterfactual, since not being implemented? It is this very weak social influence on which we focus.

In order to assess how others’ behavior can affect one’s own generosity, we experimentally implement a sequence of three successive games: first, the ultimatum game, second, the yes-no game, and third, the impunity game, or (between subjects) in the reverse order. All three games involve a proposer making an offer and a responder accepting or rejecting it.1 Changing the game type does not question the basic innovation of our design, namely conditioning on the counterfactual offer intention of somebody with whom one surely will not interact. So all three game types are embedded in the same conditioning framework but differ in how generosity intentions and behavior may be affected by strategic concerns: hardly at all in case of impunity, quite a bit in yes-no games with veto power but without monitoring the offer and finally in ultimatum bargaining granting both, veto power and monitoring. The advantage of studying such closely related games with increasing strategic influence of responders is to test whether and how weakest social influence varies when strategic considerations become more important.

By allowing to condition only on purely counterfactual and therefore outcome-irrelevant intentions of others, we study the, in our view, weakest social influence and we confirm that such influence of others on own generosity intentions is surprisingly strong. This suggests a context-dependency of individual choices which is usually overlooked by data on actual outcomes, specifically those who fail to record the effect of purely counterfactual intentions of others, learned through communication devices. Such social effects cannot be detected and tested via sequential or recursive donation experiments admitting sanctioning, reciprocity, peer pressure, conformity, reputation formation, competition in helping and generosity.

Although the impunity game2 is most suitable for eliciting intrinsic generosity intentions, we also investigate conditional generosity in case of sanctioning power via ultimatum and yes-no games. Compared to the impunity game (IG), the yes-no (YN) and the ultimatum game (UG) both grant sanctioning power to the responder but differ in information when possibly sanctioning:3 the responder does (not) know the offer in the ultimatum (yes-no) game and can sanction the proposer via refusing the offer implying zero profit for both. In the impunity game, the responder cannot sanction the proposer but can still refuse the offer. All three games allow intrinsically motivated allocator candidates to display generosity and only differ in how offers are confounded by strategic considerations. Will conditioning in generosity prevail even when disciplined by veto power with or without being able to monitor the offer? And how do actual offers compare to usual ultimatum (YN or IG game) offers?4

Our experimental setup applies to many field situations where help can only be provided by one individual only. If somebody suddenly becomes needy, e.g., due to losing a job, a sudden health problem, etc., only someone nearby may learn about such an emergency and being able to help. Thus, in the jargon of the literature on bystander effects in prosocial behavior (see Fisher et al. [8] for a review), we focus on the case of a single bystander. A reason for a single bystander might also be that victims of bad luck or circumstance often are ashamed and hide their neediness as much as possible beyond revealing their fate to a single bystander.

Another crucial aspect of our experimental design is that generosity intentions can only be compared qualitatively. In our view, this appeals to field situations where each potential bystander would provide specific services and donation which can be compared only qualitatively via “more or less generous than what I intended to offer”. Specific examples could be that, in case of a job loss, one bystander offers advice for finding a new job whereas another potential bystander helps out with money. In case of a health problem, one bystander might accompany the victim to the hospital whereas another might help out with food and related services. In such situation we often can judge who helps more, respectively less, however without being able to specify the conditions for both potential bystanders providing exactly the same help. Our experimental setup captures the qualitative comparability of generosity intentions by maintaining their numerical measurability.

With regard to reciprocity (e.g., Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger [9] and Levine [10]), it is not social dependence per se but the fact that it is triggered by the weakest social influence what we want to investigate and confirm experimentally by allowing subjects to condition their own offers on intended offers of others. Therefore we confirm that generosity is not only dependent on intrinsic or strategic characteristics. Relating our study to the literature on peer effects (see, for instance, Gächter et al. [11] and Gächter et al. [12]), the novelty is that we do not condition on the behavior of peers but only on the counterfactual intention of just one anonymous other.5 Moreover, in our experiment, allocator candidates receive feedback information only on their own outcomes to discourage conformity seeking (see Carpenter [13] and Bardsley and Sausgruber [14]).

Our design excludes joint generosity6 since only one of two allocator candidates is randomly selected to actually help: when helping, help by others is excluded, i.e., our design excludes competition in generosity. Moreover, our design has its focus on conditional generosity and not on conditional cooperation7 since we (i) randomly match participants in each interaction, (ii) give them the possibility to condition on the purely counterfactual generosity intention of an anonymous other and (iii) finally feature the receiver as a third participant.

The data confirm that the intrinsic generosity concerns of most participants are influenced by weakest social influence: most of them adjust their offers upwards as well as downwards depending on another’s intended offer in all three games. Thus intrinsic generosity concerns are cognitively generated on the spot depending on the game played as well as on those played before. The evidence of conditional generosity is surprisingly strong, even in the worst-case scenario for conditioning with the weakest form of social influence, i.e., in IG games. However, significant immunity also occurs in the form of not reacting to social influence and maintaining one’s own independent offers, as well as a self-serving tendency in conditioning via larger adjustments downwards than upwards, i.e., participants react asymmetrically to a larger than a lower counterfactual generosity intention.

Our results question the stability of “social preferences” (see the survey by Cooper and Kagel [18]) which would rule out conditioning on an other’s intended offer which is purely counterfactual and payoff-irrelevant. Moreover, belief-based other-regarding concerns such as let-down aversion would have to argue that counterfactual intentions signal what responders expect to be offered.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 formally describes the social environment based on the three game types with the impunity game as the main condition. The experimental protocols and research questions are described in Section 3. The main findings are reported and statistically confirmed in Section 4, which is largely devoted to evidence for conditional generosity. Section 5 reports on acceptance rates and payoffs, while Appendix A distinguishes between behavioral patterns. Appendix B concludes. In Appendix A, the translated version of the Instructions is reported for one treatment only (since the other treatment differs only in the order in which the games are played).

2. The Social Environment

Participants are matched in pairs of allocator candidates. Each pair consists of one allocator candidate (e), whose offers to the non-endowed responder are even integers ranging from €0 to €22, and one allocator candidate (o) whose offers are odd integers ranging from €1 to €23.8 Being even (respectively odd) is randomly selected by the computer and privately communicated to participants before they choose their strategy vector. While not yet knowing whether they are actually endowed, each candidate chooses an intended offer and two adjusted offers, and ; the former higher than or equal to, and the latter lower than or equal to the own intended offer . Which of the two adjusted offers and will be actually granted when candidate i is endowed depends on whether the other candidate intends to offer more () or less (). In addition to their offer profiles (,,), allocator candidates choose their response depending on the game type:

- in IG and UG, each sets an acceptance threshold (respectively ) based on the same integer restrictions for ; and

- in YN, each decides between unconditional acceptance () and rejection ().

Thereafter, each allocator candidate i in a pair is randomly selected with probability 1/2 as proposer and endowed with either or depending on (respectively o). This endowed proposer (e or o) confronts an opposite (o or e) non-endowed candidate of another pair in the responder role so that an even (odd) offer is accepted or rejected according to an odd (even) acceptance threshold in IG and UG. Since intended offers are never equal within a pair of allocator candidates,9 the factual offer of the actual proposer is either the downward adjusted offer or the upward adjusted offer , with j denoting the non-endowed candidate in i’s pair. Participants’ payoffs depend on the game type as follows:

- in UG, proposer i, with either or , earns , and responder j, with , earns when the offer is accepted, that is when ; both, proposer and responder, earn zero when the offer is rejected, that is, when ;

- in YN, proposer i, with either or , earns , and responder j, with , earns when the offer is unconditionally accepted, that is, when ; both proposer and responder earn zero when the offer is unconditionally rejected, that is, when ;

- in IG, proposer i, with either or , earns irrespective of the responder’s acceptance threshold, and responder j, with , earns when and zero otherwise.

Compared to UG and YN, the responder in IG has no material punishment power but rather, has the power in determining and “voice”, which is granted by informing the allocator whether or applies.10 The benchmark solutions, based on common monetary opportunism and (at most) once repeated elimination of weakly dominated strategies, are:

- in IG and UG, responder i sets when and when , while in YN responder i, with , sets ;

- in each game type, proposer i, with , sets and if and if ;

- finally, anticipating leads to for and for optimal.

For all games the outcome predicts little or no generosity by proposers who rely on the lowest positive offer (in YN, also the second lowest).11,12 The choice of is ambiguous: if not actually offering, one’s choice of is payoff irrelevant. If selected as the actual proposer, one can implement the optimal offer via and not adapt, but may also adapt to any final offer via and by choosing an extreme offer intention ( when or when ). Anticipating how one’s own offer intention may influence another’s actual offer with is not captured by the benchmark prediction due to its assumption of commonly known opportunism in the sense of own payoff maximization.

If predicting common(ly known) rationality, one would not expect conditioning on another’s counterfactual intention about which one is only qualitatively informed, nor outcome dependence on game types as well as on their sequence and learning by playing the same game repeatedly. When planning the design, on the contrary, we were quite confident that fairness is a social norm and that therefore generosity maybe affected by the generosity (intention) of an (anonymous) other. Rather than confirming stable (payoff-based) social preferences, we expected all of the above aspects to matter. Especially, we hypothesized that

- the overwhelming tendency of participant is conditioning in the sense of , meaning that one anticipates to be influenced by another’s intention;

- downward adjustments, , to be on average larger than upward adjustments, , i.e., when participants adjust, they do so in a self-serving way;

- a significantly positive minority of participants does not adjust at all either due to or by avoiding information about another’s intention via , implying that is implemented, respectively via , implying that is implemented.

Whereas these hypotheses were predicted to hold across (sequences of) game types and rounds of playing the same game, we expected

- a lower frequency of and, if so, an average decrease of with sanctioning power in YN than IG and when it lowest frequency when sanctioning is based on monitoring as in UG;

- persistent heterogeneity of adaptation patterns in case of , e.g., more than , and more so in IG than in YN than in UG;

- a decline of average intended generosity and actual offers across the nine successive rounds of play which are stronger for IG than for YN than for UG.

Relating our setup and hypotheses to studies allowing for “moral wiggle room”13 and confirming aversion to appear “unfair” either by seeking for circumstances where own self-servingness is less transparent, e.g., by avoiding information about others’ neediness, respectively about more generosity of other donors (Spiekermann and Weiss [21]), or to exploit such circumstances when confronting them (Dana et al. [7] and Dana et al. [22]). What remains intransparent for the needy recipient in our setup is how the actual offer came about: is it due to “object norm complying” (Spiekermann and Weiss [21]) in the form of or and , respectively and , or to adapting to another’s intention in case of ? In our setup profiles and which of the two offers or in case of determined the actual offer remains hidden for recipients. So if proposers want to justify self-servingness, they can only appeal to the intransparency of how their actual offer came about. For example, they may argue that their offer intention has been more generous but that another’s lower generosity intention has triggered their meager offer rather than their more generous offer .

3. Experimental Protocol

Each subject is confronted with all three game types whose sequences monotonically vary (between-subjects) in veto power: in treatment T1 with UG→YN→IG veto power is decreasing, and in treatment T2 with the reverse order, veto power is increasing. Games with the strongest (respectively with no) sanctioning power of responders, that is, UG (respectively IG) are played first in order to exclude path dependence or last in order to assess experience effects with the two other game types. To distinguish spillover effects from experiences with related games from learning when the same game is played repeatedly, each game type is encountered in three successive rounds before switching to another game type, or when reaching the last (ninth) round.14 Only one randomly selected round of the nine successive rounds is paid (to avoid experimental house-money effects).

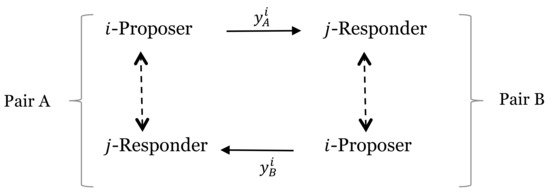

In order to guarantee newly formed pairs of allocator candidates in each round of playing the same game type the software matches two participant pairs, A and B (see Figure 1), whose members are matched as even-odd (respectively odd-even), and therefore subjected to different integer restrictions.15 The randomly endowed candidate and actual proposer i, with , in one pair confronts the non-endowed candidate j, with and , of the other pair as "needy", that is, as non-endowed responder. So the factual offer by the proposer i in pair A (denoted in Figure 1) is accepted or rejected by the responder j in pair B, and the factual offer by the proposer i in pair B (denoted in Figure 1) is accepted or rejected by the responder j in pair A. Conditioning is based on comparing intended offers within a pair (the dashed bi-directed arrows in Figure 1), whereas offers are made across pairs (the one-direction bold arrows in Figure 1). Obviously this allows for each member of such a group with four participants to confront a new allocator candidate in the three successive rounds with the same game type.

Figure 1.

The matching within and between pairs. Notes: Solid arrows represent the factual offers by the proposers, while bi-directed arrows represent the conditioning on offers within pair A and pair B.

In each round, participants are privately informed about their current (odd or even) integer restrictions. Then, their offers in the proposer role and their acceptance behavior , or in the responder role are elicited (strategy vector method).16 Finally, participants are informed about their role (endowed proposer or needy responder) in the current round. Via feedback information, responders learn the actual offer when accepting it: when rejecting, only their own payoff (zero) is communicated. Proposers learn about their own payoff and the acceptance or rejection of their offer. The latter is explicitly disclosed to the proposers in the (non-private) IG, who in UG and YN can usually (for ) infer their offer’s rejection from the 0-payoff. Proposers remain unaware of the acceptance threshold or . Both actual players know after playing how much each of them has earned and in which role (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Feedback by treatments.

In total, 144 participants were recruited from a pool of (under)graduate students in Economics, Law and Political Science at Luiss Guido Carli University in Rome using Orsee (Greiner [24]). No subject participated in more than one session. Between-subject treatments T1 and T2 used the same protocol in the reverse order. The software is based on z-Tree (Fischbacher [25]). The experimenter read aloud the written instructions (see the translated instructions in Appendix A) before subjects could privately ask questions and then begin with the experiment. The experiment is compliant with the laboratory ethical code approved by the ethical board.17

4. Data Analysis and Empirical Findings

Since participants provide in each of the three rounds of each game type an offer profile and a response decision whose format depends on the type of game, the data comprises nine successively elicited strategy vectors of each participant of which, due to feedback information between rounds only the initial ones are independent.18

We therefore focus our data analysis on controlling interdependence via individual and group-level error terms. The latter are based on (across nine successive rounds) constantly applied rematching groups with four participants each, each of whom confront a new partner in all each of the three rounds within the same game type (see Figure 1), which is then repeated for the later game type(s). This obviously guarantees independence from group-level data comprising -strategy vectors. Since there are 36 groups our data file contains strategy vectors which will be statistically analyzed either globally or by distinguishing the game type sequence of game types. Our main findings, especially for conditioning in generosity revealed by offer profiles () with , are analyzed first with descriptive and graphical data analysis of behavioral adjustments, controlling for statistical significance using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test (WRST hereafter) for independent samples and Wilcoxon Signed Rank-Sum test (WSRST hereafter) for matched samples, applied across all game types or separately for each game type. The choice dynamic is analyzed by tobit estimation; we control for group effect through multi-level analysis and panel regression. Due to our focus on conditional generosity, we concentrate on offer profiles, especially when distinguishing behavioral patterns, and deal with acceptance behavior and its payoff and efficiency implications only marginally.

4.1. Confirming Conditional Offering

Our data show that most participants condition their own offers on another’s purely counterfactual generosity intention: offer profiles with account for 831 out of 1296 observations ().19

In Table 2 average offer profiles (), acceptance behavior (), and difference between independent and adjusted offers ( and ) for all games, and separately for UG, YN, and IG, and treatments T1 and T2 are reported.

Table 2.

Average offers , acceptance behavior and differences , .

When all games and both treatments are considered, the average20 upward adjustment is equal to (see Table 2, All Games) and reveals that reacting to another’s generosity intention can considerably increase one’s own sacrifice. Since the average downward adjustment is equal to , offer profiles with display an average difference equal to .

Result 1.

Across all game types nearly two thirds of all offer profiles () leave substantial room via positive for reacting to another’s generosity intention.

Another consistent feature of offer profiles across all game types and treatments is that participants behave in a self-serving manner, by adjusting more strongly downward than upward. In fact, is significant for all game types in both treatments (see Table 2, last column; WSRST, p-value ).

Result 2.

Most offer profiles allowing for conditioning adjust in a self-serving way, more downward than upward.

When looking at offer profiles within each game, we confirm that they leave substantial room for reacting to another’s generosity intentions via positive . Furthermore, the self-serving behavior in adjusting ) is confirmed in IG and YN, both across and within treatments (see Table 2, last column; WSRST, p-value ; for IG in T2, p-value ). In UG, on the contrary, there is no significant difference in average downward and upward adjustments neither across nor within treatments. This suggests that strategic concerns, which are largest in UG, dampen the reactivity of conditioning and may question (weak) social influence.

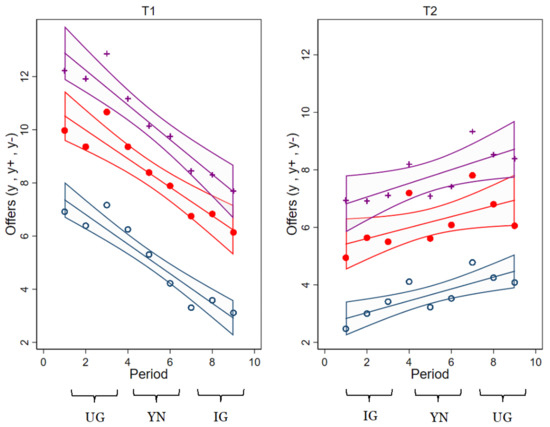

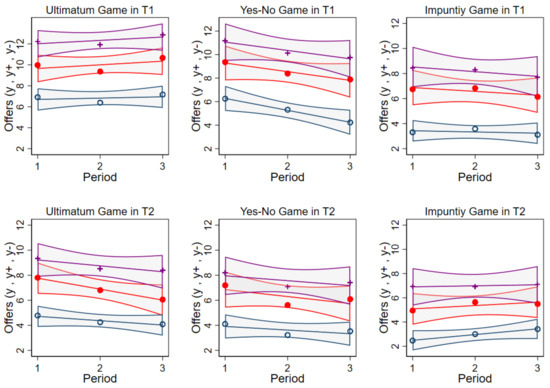

Looking at the average independent and adjusted offers within game types, we find that in UG they are higher that those in YN, which are in turn higher than those in IG, and this finding is consistent with the decreasing sanctioning power of responders. Furthermore, we find no treatment effect on offers in IG whereas average offers in UG are lower in treatment T2 than in treatment T1 (see Table 2, WRST, p-value ). Thus, fairness concerns in UG are weaker when played after the other game types. Similarly, in YN average offers are significantly smaller when the game is preceded by IG rather than UG (see Table 2, WRST, p-value ). Figure 2 and Figure A1 (Appendix B) illustrate the evolution of independent and adjusted offer profiles across the three successive rounds of the three game types for both treatments. They confirm no treatment effect on offers in IG and that average offers and in UG and YN are lower in treatment T2 than in treatment T1. We expected dominance of conditioning but less reactivity (at least in adjustment size) in case of sanctioning power, as strategic concerns may question weak social influence. However, due to conditional generosity, in IG downward and upward adjustments do not significantly differ from those in UG and YN (except for upward adjustments in UG and treatment T1).

Figure 2.

Independent offer and adjustments by treatment. Notes: Average values per period are indicated by + for , • for y, and ∘ for while lines represent linear prediction plots along with a confidence interval (CI 95%).

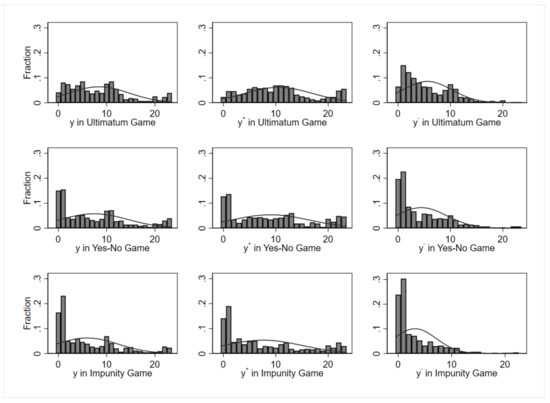

Looking at the fraction of offers across games in Figure 3, the reaction to the downward adjustment is more evident in IG (WSRST, p-value in Table 2) but it is relevant in all games. The figure also reveal that all offer types display a low single peak for YN and IG, whereas for UG this applies only to downward adjusting offers .21 More interestingly, the figure reveals that in IG a large share (54%) of downward adjusted offer are at the minimum level (either zero or one).

Figure 3.

Fraction of offers . Notes: The range of offer profiles is from 0 to 23 to encompass both odd and even offers. The graph encloses normal density curve for each histogram.

As far as response behavior is concerned, IG responders (with no veto power) state systematically lower acceptance thresholds (on average 2.315) than UG responders (on average 3.639) who claim nearly twice as much in treatment T1 (see Table 2, 4.685 respect to 2.593, WRST, p-value ). Whereas there is no treatment effect on response behavior in IG: acceptance thresholds in treatment T1 (2.454) and treatment T2 (2.176) do not significantly differ (see Table 2, WRST, p-value ).22 The acceptance share in YN is close to 100%, in line with earlier YN-experiments (see Güth and Kocher [26]).

These results show that conditioning in IG is a stable inclination which emerges even with the weakest social influence, but also that conditioning is game dependent. The latter justifies our more systematic attempt to assess conditioning not only in case of impunity but also when sanctioning is possible. Nevertheless, most participants, overall allow themselves to be influenced by whether another’s intent to help more (respectively less). In our view, this suggests that (intrinsic) generosity concerns are usually cognitively generated on the spot, depending on the game type presently played as well as on treatment, i.e., on the game that is played before.

Result 3.

The treatment effect is game dependent:

- (i)

- for IG differences in offers and acceptance thresholds when played first or last are minor and mostly insignificant;

- (ii)

- for UG average offers and acceptance thresholds are much and significantly smaller when UG is played last; and

- (iii)

- for YN it does not matter for response behavior whether it is preceded by UG or IG but average offers are significantly smaller when YN is preceded by IG rather than by UG.

The regression analysis of the dynamics of offer profiles across rounds is presented in Table 3 and Table 4. The analysis is based on twelve normalized offer levels .2324 Looking at the three games separately, Table 3 shows that in IG being a proposer in the previous round (L.proposer)25 has a positive effect on offers in the next round, implying that one is willing to offer more when having been endowed before, whereas this is not significant in UG. Past profits (L.Profit)26 have a negative effect on offers in IG and YN: one becomes greedier after having earned more. Checking whether being an odd or even allocator candidate has an impact on offers reveals that when odd, there are more downward adjustments toward the minimum level, which for odd is still positive (and therefore seemingly more tolerable).27

Table 3.

Choice dynamic by Game (1).

Table 4.

Choice dynamic by Game (2).

In Table 4 we perform a similar tobit estimation controlling for being a successful proposer in the previous round (L.Success×L.Proposer).28 The significance of this variable in UG shows that being a proposer has a positive effect on offers in the following round, only when one’s proposal has been previously accepted, whereas when proposals were rejected, offers in the following round are lower. Round variable accounts for the effect of the last period and it is never significant.

4.2. Efficiency Analysis

We assess the average acceptance rate across games and the associated efficiency: in IG the only efficiency loss is associated to rejected offers, while in YN and UG the whole endowment , with , is lost when the offer is rejected. Table 5 lists the average payoff by acceptance rate in the three game types (‘Total’ refers to both accepted and rejected offers). There is less acceptance in IG (36%) than in UG (29%) and in UG than in YN (1.4%). Although the rejection rate in IG is higher, its average payoff is higher (21.128) as its proposers are not harmed by rejection. Nevertheless, when considering the average proposer payoff in case of acceptance, proposers earn more in IG than in UG ( versus , WRST, p-value ) and, non-significantly, in YN ( versus , WRST, p-value ), while responder payoffs are higher when accepting in UG ( versus in IG and in YN, WRST, p-value .).

Table 5.

Payoff analysis by acceptance rate (actual plays).

To analyze efficiency independently of random role selection, we simulated the payoffs for all possible pairs of factual offers and acceptance threshold (respectively ) of the corresponding responder (Table 6).2930 The simulated average results—relying only on the first round with independent individual choices—include all possible pair matchings of participants and provide a robustness check of our efficiency analysis. The simulated plays confirm (see Table 6) that the rejection rate is higher in IG (44%) than in UG (25%);31 proposer payoffs in the case of acceptance are higher in IG (16.8) than in UG (12.0); whereas responder payoffs are higher in UG (10.5) than in IG (5.7) (WRST, p-value in both cases).

Table 6.

Payoff analysis by acceptance rate (simulated data).

4.3. Categorization of Offer Profiles and Individual Types

Our data confirm the dominance of other-regarding concerns but also reveal considerable heterogeneity. In our setting, heterogeneity in conditioning can be assessed via individual offer profiles by distinguishing the following mutually exclusive patterns:

- -

- Reactive (R): if and , one adjusts upward as well as downward.

Reactive offer profiles can be further differentiated via:

- -

- Reactive selfserving (Rs): , that is, one reacts more strongly downward than upward;

- -

- Reactive non-selfserving (Rns): if , that is, one abstains from conditioning in a self-serving manner.

A participant who is non-reactive may still adjust the intended offer, however only in one direction. We distinguish:

- -

- Adapting Downward (D): if ; and

- -

- Adapting Upward (U): if .

Finally, the immunity pattern (I) means to not adapt at all:

- -

- Immune (I): if .

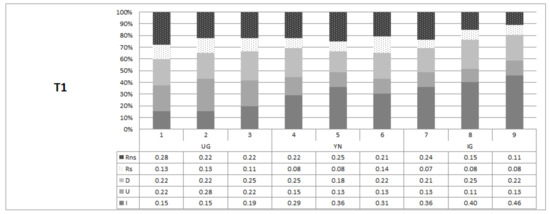

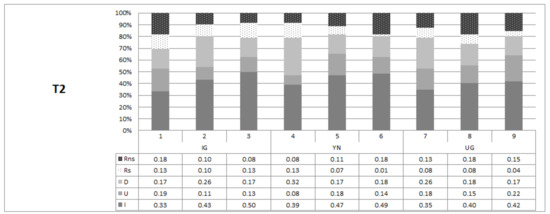

Figure 4 and Figure 5 visualize how the shares of these different categories of participants evolve across the nine rounds for treatments T1 and T2. In IG, as expected, the immunity share is larger than in the other games, both in treatment T1 (46% in the last round) and T2 (50% in the last round). Furthermore, the immunity share is rather stable in IG (reacting and adapting pattern together account for at most only 50%). In UG, on the other hand, the immunity share is larger in T2 (42% in its third round) than in T1 (19% in the last round). Overall, conditioning survives the repeated play of different game types, irrespective of their sequence.

Figure 4.

Distribution of types by period in treatment T1. Notes: Each cell entry report the share of choices based on the individual offer profile types: Reactive non-selfserving (Rns), Reactive selfserving (Rs), Adapting Downward (D), Adapting Upward (U), and Immune (I) in Treatment 1.

Figure 5.

Distribution of types by period in treatment T2. Notes: Each cell entry report the share of choices based on the individual offer profile types: Reactive non-selfserving (Rns), Reactive selfserving (Rs), Adapting Downward (D), Adapting Upward (U), and Immune (I) in Treatment 2.

On the individual level, we distinguish participants who are consistently either of the I- or R-type in all three rounds of a given game type. Always I-participants are 43 in IG (129 observations) respectively, 39 in YN (117 observations), and 24 in UG (72 observations) whereas always R-participants are 19 (57 observations) in IG, 22 in YN (66 observations), and 16 (48 observations) in UG (see Table 7). As expected, the average I-type offer is particularly low in IG and increases when the game becomes more strategic, in the sense of possible sanctioning and (not) monitoring the offer in (YN, ) UG (). Reactive participants have a similar frequency in IG and UG; moreover, their initial offers are similar in the two game types (respectively and ). However, average offers are adjusted more in IG than in UG, both upward and downward.

Table 7.

Immune and reacting participants average offers and acceptance behavior.

5. Conclusions

Our data confirm conditional generosity: most participants condition their own offers based on another’s purely counterfactual generosity intention in all three different game types we have considered. This even holds for the weakest social influence setup with no room for reciprocity (like in impunity games) and no competition in helping (since only one of the two allocator candidates will be the actual proposer) . The evidence is revealed by positive offer differences , and across all three games and both sequence treatments and is surprisingly strong: participants are influenced by whether another intends to help more (respectively less). Note that this predominance of conditioning questions that stating one’s generosity intention is not behaviorally irrelevant. Strategic manipulations via offer intentions are possible and likely successful.32 We also found that conditioning is game and treatment dependent and survives the weakest social influence (in particular it survives even in the last round of the impunity game, in both sequences). In particular, participants in IG and YN adjust more downwards than upwards while strategic concerns in UG provide larger and symmetric adjustments.

Most importantly, participants, who are socially influenced, display greater fairness concerns by offering considerably more than the participants immune to social influence.

Altogether, our results confirm the intuition that (intrinsic) generosity is more often than not prone to social influence, even if very weak. Our results suggest that social preferences are not given and stable but have to be generated in a context dependent way, where context can include rumors about others’ intentions, even if only qualitatively comparable, but also incorporate strategic aspects, such as sanctioning and monitoring of offers. Hopefully our data can help in understanding how one’s own (intrinsic or also strategic) generosity intentions are possibly questioned and adjusted when learning about another’s intentions, either only qualitatively (as in our setup and likely in the field) or quantitatively. In spite of the field relevance of our experimental setup to clearly confirm such results required some rather special aspect like ruling out competition in helping the needy and endowing only one allocator candidate. Avoiding such aspects would enrich the social context what could trigger confounding effects which we wanted to avoid. In this sense our setup is admittedly stylized.

Acknowledgments

The research in this paper was financed by the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, Bonn, Germany.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A.

Translated instruction for treatment T2.

Instructions to Participants

Introduction

Welcome to our experiment! During this experiment, you as well as the other participants will have to take several decisions. Please read the instructions carefully. Your decisions, as well as the decisions of the other participants will determine your payoff according to rules, which will be explained shortly. The earnings during the experiment are expressed in euros (€). In addition to the earnings obtained over the course of the experiment, you will receive a show-up fee of €3.00. Please note that hereafter any form of communication between the participants is strictly prohibited. If you violate this rule, you will be excluded from the experiment with no payment. If you have any questions, please raise your hand. The experimenter will come to you and answer your questions individually.

Description of the Experiment

This experiment is fully computerized. After reading the instructions, before starting the experimental task, you will have to answer to few control questions; these questions are going to help you to understand the experimental task, and they have no effect on your final earnings.

The experiment is composed by 5 control questions (to help you understanding the experiment), three phases (Phase I, Phase II and Phase III) and a final questionnaire. Each phase lasts 3 rounds and in each round you can be a proposer or a responder. Your role will be randomly selected by the computer with probability equal to 1/2 and communicated at the end of each round.

The proposer will be endowed with an initial amount of euros which can be shared with a responder in the experiment. A responder will have no endowment and can accept or reject the offer of the proposer.

Note: Your task in each round is to make choices that pertain your role as a proposer and your role as a responder. Beware that you will have to take your decisions before knowing if you will be a proposer or a responder.

Phase I

At the beginning of each round in Phase I, you will be selected either as O(dd) participant or as an E(ven) participant with probability 1/2. If you are E your initial endowment is €22 and you can allocate only even values. If you are O your initial endowment is €23 and you can allocate only odd values. After that, you will be randomly paired with another participant, whose identity will not be disclosed to you. If you are an O(dd) participant, you will be paired with an E(ven) participant; similarly, if you are an E(ven) participant, you will be paired with an O(dd) participant. The paired participant will always be different from the one in the previous round.

Both you and your paired participant are asked to take the following decisions:

- first, you have to decide, individually and independently, how much of your endowment you to want to give to a responder (different from your paired participant) if you will be selected as a proposer. If you are an O(dd) participant, you can choose one between these numbers . If you are an E(ven) participant, you can choose one of the numbers .Observe that both types of participants have the same number of possible choices, i.e., twelve, and that the difference between the minimum and the maximum choice, i.e., 22€, is the same for both types of participant.

- Second, you have to decide, individually and independently, how much you want to update your initial proposal if you will be selected as a proposer in the two following situations:

- –

- the proposal of your paired participant is larger than yours; in this case you can either confirm or increase your initial proposal;

- –

- the proposal of your paired participant is smaller than your; in this case you can either confirm or decrease your initial proposal.

Remember that in each of the two cases, your updated proposal can only be an odd number or even number depending on whether you are an O or an E candidate.Note: Beware that you will be asked to update your initial proposal before knowing if the other has decided to propose more than you or less than you. - Third, you have to decide, individually and independently, what proposals you will accept if you will be selected as a responder. In particular, you have to decide an acceptance threshold such that all proposals larger than the threshold will be accepted and all proposals lower than the threshold will be rejected.Remember that the acceptance threshold can only be an odd number or even number depending on whether you are an O or an E candidate.

After all participants have taken their decisions regarding the initial proposal, the updated proposals and the acceptance threshold, the computer will

- adjust the proposals of each participant depending on whether the initial proposal of the paired participant is larger or smaller than the own one;

- select, for each pair of participant, who is the proposer and who is the responder;

- randomly match each proposer with a responder from a different pair than the initial one and, similarly, randomly match each responder with a proposer from a different pair than the initial one.

Observe that:

- –

- O(dd) proposers will be matched with E(ven) receivers and that E(ven) proposers will be matched with O(dd) receivers;

- ●

- the proposal communicated to the receiver will be the adjusted one (and not the initial one).

Your payoff in Phase I will be calculated as follows:

- if you are a proposer, your payoff will be equal to your endowment minus your offer both in case the offer is above or below the responder’s acceptance threshold.

- if you are a receiver, your payoff will be equal to

- ∘

- the proposer’s proposal if this is larger than your acceptance threshold;

- ∘

- equal to zero if the proposal is smaller than your acceptance threshold.

Summing up, at the end of each round the computer communicates:

- –

- if you are proposer or responder;

- –

- if your are a proposer, you will be communicated that you were selected as a proposer and you will be informed about your final payoff and the payoff of the responder who received your proposal;

- –

- if you are a receiver, you will be communicated that you were selected as a receiver and you will be informed about your final payoff.

Note: The computer will not inform you about the initial proposal of the paired participant with whom you interact at the beginning of each round.

Phase II

In Phase II, proposers are asked to take the same type of decision described in Phase I, therefore, the same instructions apply in this case.

The decision that you have to take for the case in which you will be selected as receiver is different in this Phase. In particular, in Phase II you have to state, individually and independently, if you want to accept or refuse the proposal you will receive by selecting one of the two options Yes, No.

Remember that you have to state your decision without knowing the proposal you will receive.

Your payoff in each round of Phase II will be calculated as follows:

- if you are a proposer, your payoff is

- ∘

- the initial endowment minus you proposal if the receiver selected the Yes option;

- ∘

- zero if the receiver selected the No option;

- if you are a receiver, your payoff

- ∘

- is the proposer’s proposal whether you accepted the offer;

- ∘

- zero whether you refused the offer.

Summing up, at the end of each round the computer communicates:

- –

- if you are proposer or responder;

- –

- your final payoff.

Phase III

In Phase III, proposers are asked to take the same type of decision described in Phase I and Phase II, therefore, the same instructions apply in this case.

The decision that you have to take for the case in which you will be selected as receiver is different in this Phase. In particular, in Phase III you have to state, individually and independently, what proposals you will accept if you will be selected as a responder. In particular, you have to decide an acceptance threshold such that all proposals larger than the threshold will be accepted and all proposals lower than the threshold will be rejected.

Your payoff in Phase III will be calculated as follows:

- if you are a proposer, your payoff will be equal to

- ∘

- your endowment minus your offer when your offer is above the responder’s acceptance threshold;

- ∘

- Zero, when you offer is below the responder’s acceptance threshold;

- if you are a receiver, your payoff will be equal to

- ∘

- the proposer’s proposal if this is larger than your acceptance threshold;

- ∘

- equal to zero if the proposal is smaller than your acceptance threshold.

Summing up, at the end of each round the computer communicates:

- –

- if you are proposer or responder;

- –

- your final payoff.

Your Final Earning for This Experiment

After completing the experiment, a lottery administrated by the computer will randomly select one round to be considered for payment. Each round hs the same probability to be selected (1/9). The result will be display it on your screen the corresponding payoff you made in that round.

Your total payoff from the experiment will be equal to the sum of:

- –

- the payoff that you realised in the selected round;

- –

- the participation fee of €3.

After having finished the experiment, but before receiving your payoff, you will be asked also to fill up a short questionnaire about your demographics and other few questions. Please remain at your cubicle until asked to come forward and receive payment for the experiment.

Appendix B.

Figure A1.

Independent offer and adjustments by game and treatment. Notes: Average values per period are indicated by + for , • for y, and ∘ for while lines represent linear prediction plots along with a confidence interval (CI 95%).

Table A1.

Choice dynamic by Game (1)-controlling for single sessions.

Table A1.

Choice dynamic by Game (1)-controlling for single sessions.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UG | YN | IG | UG | YN | IG | UG | YN | IG | |

| L.Proposer | 0.59 | 1.39 * | 5.13 *** | 0.38 | 1.50 * | 6.37 *** | 0.52 | 1.38 ** | 4.51 *** |

| (0.39) | (0.79) | (1.48) | (0.40) | (0.84) | (1.57) | (0.33) | (0.68) | (1.32) | |

| L.Profit | −0.01 | −0.13 ** | −0.31 *** | −0.03 | −0.15 ** | −0.40 *** | −0.04 * | −0.14 *** | −0.30 *** |

| (0.03) | (0.06) | (0.08) | (0.03) | (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.02) | (0.05) | (0.07) | |

| Round | 0.16 | −0.09 | −0.36 | 0.25 | −0.16 | −0.29 | 0.25 | −0.38 | −0.15 |

| (0.26) | (0.29) | (0.28) | (0.21) | (0.27) | (0.27) | (0.25) | (0.25) | (0.32) | |

| Odd | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.94 | 0.13 | −0.25 | −1.34 ** | −1.03 *** | −0.39 | −1.14 ** |

| (0.41) | (0.52) | (0.60) | (0.38) | (0.54) | (0.62) | (0.32) | (0.42) | (0.50) | |

| Treatment | −2.54 *** | −2.50 * | −1.24 | −1.97 ** | −3.02 ** | −1.45 | −1.60 ** | −0.91 | 0.11 |

| (0.94) | (1.40) | (1.56) | (0.93) | (1.50) | (1.80) | (0.68) | (1.09) | (1.25) | |

| Session 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | |

| Session 2 | 0.46 | 0.77 | 0.46 | −0.18 | 1.39 | 0.76 | −0.07 | 0.66 | 0.38 |

| (0.84) | (1.42) | (1.45) | (0.86) | (1.39) | (1.66) | (0.72) | (1.14) | (1.14) | |

| Session 3 | 0.34 | −0.63 | −0.77 | 0.66 | −0.73 | −0.93 | −0.01 | 0.45 | 0.27 |

| (0.88) | (1.32) | (1.43) | (0.87) | (1.42) | (1.55) | (0.59) | (0.98) | (1.07) | |

| Session 4 | 0.65 | 1.25 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 1.24 | 0.67 | 1.49 | 1.07 |

| (0.77) | (1.16) | (1.29) | (0.77) | (1.27) | (1.36) | (0.51) | (0.97) | (1.00) | |

| Session 5 | 1.89 * | 1.38 | 0.89 | 1.35 | 1.67 | 1.66 | 0.66 | −0.03 | 0.12 |

| (0.97) | (1.61) | (1.65) | (1.04) | (1.61) | (1.82) | (0.73) | (1.18) | (1.23) | |

| Session 6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | |

| Cons | 6.32 *** | 6.37 *** | 5.13 ** | 6.72 *** | 8.58 *** | 6.51 ** | 4.28 *** | 3.44 * | 1.15 |

| (1.53) | (2.25) | (2.37) | (1.47) | (2.42) | (2.66) | (1.14) | (1.75) | (2.06) | |

| cons | 3.22 *** | 4.75 *** | 4.76 *** | 3.24 *** | 4.87 *** | 5.12 *** | 2.53 *** | 3.62 *** | 3.60 *** |

| (0.19) | (0.30) | (0.35) | (0.16) | (0.28) | (0.31) | (0.15) | (0.28) | (0.31) | |

| N | 288 | 288 | 288 | 288 | 288 | 288 | 288 | 288 | 288 |

| LL | −708.49 | −652.48 | −608.18 | −736.86 | −698.38 | −666.38 | −611.11 | −529.90 | −466.66 |

| pseudo | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| F | 3.49 | 2.06 | 2.80 | 3.75 | 1.87 | 3.84 | 4.45 | 2.28 | 3.28 |

Notes: Tobit estimation with robust errors (clustered on individuals) censored at the lowest value (0). The dependent variable is the twelve normalized offer levels . when and when when and when when and when Covariates included in the regression are the lagged profit and role, the “odd” dummy to specify whether the participant is asked to set an odd rather than an even offer, and the treatment. “Round” variable refers to the three periods of each phase, but due to the lagged period analysis the variable accounts for the effect of period 3. Session 6 is dropped for collinearity with Treatment variable. * indicates pvalue<.1, ** pvalue<.05, *** pvalue<.01.

Table A2.

Choice dynamic by Game (2)-controlling for single sessions

Table A2.

Choice dynamic by Game (2)-controlling for single sessions

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UG | IG | UG | IG | UG | IG | |

| L.Proposer | −1.30 * | 4.63 ** | −1.75 ** | 5.68 ** | −1.34 ** | 2.81 |

| (0.76) | (2.25) | (0.72) | (2.46) | (0.58) | (1.85) | |

| L.success | −0.70 | 0.97 | −0.41 | 1.52 | −1.00 * | 0.81 |

| (0.67) | (0.96) | (0.72) | (1.06) | (0.57) | (0.75) | |

| L.success×L.Prop | 2.97 *** | 0.56 | 3.43 *** | 0.77 | 2.83 *** | 1.67 |

| (0.93) | (1.54) | (0.87) | (1.69) | (0.70) | (1.20) | |

| L.Profit | −0.07 | −0.31 *** | −0.12 *** | −0.39 *** | −0.08 ** | −0.27 *** |

| (0.04) | (0.09) | (0.04) | (0.10) | (0.04) | (0.08) | |

| Round | 0.17 | −0.31 | 0.26 | −0.23 | 0.25 | −0.07 |

| (0.27) | (0.29) | (0.22) | (0.28) | (0.26) | (0.34) | |

| Treatment | −2.56 *** | −1.13 | −1.99 ** | −1.27 | −1.62 ** | 0.23 |

| (0.91) | (1.52) | (0.89) | (1.73) | (0.63) | (1.20) | |

| Odd | −0.19 | −0.79 | 0.04 | −1.12 * | −1.11 *** | −0.94 * |

| (0.41) | (0.60) | (0.37) | (0.62) | (0.31) | (0.49) | |

| Session 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | |

| Session 2 | 0.48 | 0.48 | −0.16 | 0.79 | −0.06 | 0.40 |

| (0.81) | (1.42) | (0.83) | (1.61) | (0.68) | (1.09) | |

| Session 3 | 0.36 | −0.53 | 0.74 | −0.56 | −0.02 | 0.57 |

| (0.83) | (1.42) | (0.82) | (1.54) | (0.56) | (1.06) | |

| Session 4 | 0.66 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 1.19 | 0.66 | 1.02 |

| (0.73) | (1.28) | (0.71) | (1.33) | (0.47) | (0.97) | |

| Session 5 | 1.94 ** | 1.09 | 1.40 | 1.97 | 0.68 | 0.42 |

| (0.95) | (1.60) | (1.01) | (1.74) | (0.68) | (1.15) | |

| Session 6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | (.) | |

| Cons | 7.19 *** | 4.11 * | 7.55 *** | 4.94 * | 5.25 *** | 0.06 |

| (1.54) | (2.45) | (1.46) | (2.62) | (1.15) | (2.09) | |

| cons | 3.16 *** | 4.73 *** | 3.15 *** | 5.04 *** | 2.46 *** | 3.51 *** |

| (0.19) | (0.35) | (0.16) | (0.31) | (0.15) | (0.30) | |

| N | 288 | 288 | 288 | 288 | 288 | 288 |

| LL | −708.49 | −608.18 | −736.86 | −666.38 | −611.11 | −466.66 |

| pseudo | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| F | 3.93 | 3.27 | 5.00 | 4.85 | 5.72 | 4.26 |

Notes: Tobit estimation with robust errors (clustered on individuals) censored at the lowest value (0). The dependent variable is the twelve normalized offer levels . when and when when and when when and when Covariates included in the regression are the lagged profit, the lagged role and success (as well as their interaction), “odd” dummy to specify whether the participant is asked to set an odd rather than an even offer, and the treatment. “Round” variable refers to the three periods of each phase, but due to the lagged period analysis the variable accounts for the effect of period 3. * indicates pvalue<.1, ** pvalue<.05, *** pvalue<.01.

References

- Andreoni, J. Giving with impure altruism: Applications to charity and Ricardian equivalence. J. Polit. Econ. 1989, 97, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. Econ. J. 1990, 100, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesterlund, L. Using Experimental Methods to Understand Why and How We Give to Charity. In The Handbook of Experimental Economics; Kagel, J.H., Roth, A.E., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016; Volume 2, ISBN 978-0-691-13999-9. [Google Scholar]

- Selten, R. Die strategiemethode zur erforschung des eingeschränkt rationalen verhaltens im rahmen eines oligopolexperiments. In Beiträge zur Experimentellen Wirtschaftsforschung; Sauerman, H., Ed.; JCB Mohr (Paul Siebeck): Tübingen, Germany, 1967; ISSN 00442550. [Google Scholar]

- Güth, W.; Huck, S. From Ultimatum Bargaining to Dictatorship—An experimental Study of Four Games Varying in Veto-Power. Metroeconomica 1997, 48, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, G.E.; Katok, E.; Zwick, R. Dictator Game Giving: Rules of Fairness versus Acts of Kindness. Int. J. Game Theory 1998, 27, 269–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, J.; Weber, R.A.; Kuang, J.X. Exploiting moral wiggle room: experiments demonstrating an illusory preference for fairness. Econ. Theory 2007, 33, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.; Krueger, J.I.; Greitemeyer, T.; Vogrincic, C.; Kastenmüller, A.; Frey, D.; Kainbacher, M. The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufwenberg, M.; Kirchsteiger, G. A Theory of Sequential Reciprocity. Games Econ. Behav. 2004, 47, 268–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.K. Modeling altruism and spitefulness in experiments. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 1998, 1, 593–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gächter, S.; Nosenzo, D.; Sefton, M. Peer effects in pro-social behavior: Social norms or social preferences? J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2013, 11, 548–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gächter, S.; Gerhards, L.; Nosenzo, D. The importance of peers for compliance with norms of fair sharing. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2017, 97, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.P. When in Rome: Conformity and the provision of public goods. J. Socio Econ. 2004, 33, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardsley, N.; Sausgruber, R. Conformity and reciprocity in public good provision. J. Econ. Psychol. 2005, 26, 664–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereby-Meyer, Y.; Niederle, M. Fairness in bargaining. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 2005, 56, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U.; Gächter, S.; Fehr, E. Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ. Lett. 2001, 71, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U.; Gächter, S. Social Preferences, Beliefs, and the Dynamics of Free Riding in Public Goods Experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.J.; Kagel, J.H. Other-Regarding Preferences: A Selective Survey of Experimental Results. In The Handbook of Experimental Economics; Kagel, J.H., Roth, A.E., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016; Volume 2, ISBN 978-0-691-13999-9. [Google Scholar]

- Di Cagno, D.; Galliera, A.; Güth, W.; Panaccione, L. A hybrid public good experiment eliciting multi-dimensional choice data. J. Econ. Psychol. 2016, 56, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, J.; Horite, Y.; Takagishi, H. The private rejection of unfair offers and emotional commitment. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 11520–11523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiekermann, K.; Weiss, A. Objective and subjective compliance: A norm-based explanation of moral wiggle room? Games Econ. Behav. 2016, 96, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, J.; Cain, D.M.; Dawes, R.M. What you don’t know won’t hurt me: Costly (but quiet) exit in dictator games. Org. Behav. Hum. Decis. Proc. 2006, 100, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizzo, D.J. Experimenter demand effects in economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 2010, 13, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, B. Subject Pool Recruitment Procedures: Organizing Experiments with ORSEE. J. Econ. Sci. Assoc. 2015, 1, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U. z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güth, W.; Kocher, M.G. More than thirty years of ultimatum bargaining experiments: Motives, variations, and a survey of the recent literature. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 2014, 108, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | Due to the strategy vector method (see Selten [4]), each participant determines independent and conditional offers in the role of proposer as well as an acceptance threshold in the role of responder. |

| 2. | See, for example, Güth and Huck [5] and Bolton et al. [6]. |

| 3. | Dictator game experiments—except when especially interested in the “moral wiggle room” (see Dana et al. [7] —unnecessarily deprive the recipient of voice and choice in addition to excluding sanctioning power, for example, when comparing them with those of ultimatum game experiments. |

| 4. | Note that UG-equilibrium multiplicity is avoided by YN as well as by IG. |

| 5. | Gächter et al. [12] focus on uni-dimensional influence based on actual donations of two successively donating dictators in three-person dictator experiments. |

| 6. | Joint generosity is explored by running charitable donation experiments in which conditioning is investigated via providing information about other earlier donations, for example, by distinguishing larger (smaller) earlier donations (see Bereby-Meyer and Niederle [15]). |

| 7. | As in Fischbacher et al. [16] and Fischbacher and Gächter [17]. |

| 8. | Due to the available amount differs between o and e so as to allow both o and e to offer the whole endowment. Moreover, the fact that paired candidates have different headings (e, respectively, o) avoids the possibility of equal intentions in sharing. |

| 9. | Although equal intentions are often maintained (see Di Cagno et al. [19]), we opted against eliciting reactions to the equality of intentions since this questions qualitative comparability. |

| 10. | In the terminology of Yamagishi et al. [20] we have implemented a non-private IG. |

| 11. | For in YN both acceptance and rejection are best responses, that is, there are two (pure strategy) equilibria. |

| 12. | UG has other equilibria with other, also fair, outcomes. These, however, rely on weakly dominated response strategies which would not survive once repeated elimination. |

| 13. | We thank one of our referee for this suggestion. |

| 14. | All three sharing games were easily understood by participants and three rounds seemed sufficient to indicate learning. |

| 15. | Participants were informed about random rematching in each round but not about its specific details. |

| 16. | Participants are first asked for an intended offer and then to submit new offers conditional on the possible qualitative information about the other’s intended offer. We try to limit experimenter demand effects (see Zizzo [23]) for a comprehensive discussion on the experimenter demand effects) by neutral instructions. Furthermore, the analysis on differences between adjustments and learning analysis should partially account for it since strategic concerns are likely to weaken demand effects. |

| 17. | Details on the committee as well as the ethical code can be found on the Cesare laboratory web-page (http://economiaefinanza.luiss.it/en/research/research-centers/cesieg/cesare-centre-experimental-economics/cesare-rent). |

| 18. | Thus, guaranteed independence of the initial profiles can only be explored in case of IG and UG as YN is never the game type played first. |

| 19. | Since offer profiles with are impossible. |

| 20. | In what follows, will denote average values. |

| 21. | This is in line with previous experiments without conditioning (see Güth and Kocher [26], for references). |

| 22. | Whether or holds allows to verify participants’ consistency, in that they would not otherwise accept their own offer. Such consistency is higher in UG (71% of adjusted offers satisfy ) than in IG (43% of adjusted offers satisfy ). |

| 23. | The offers are rescaled via when and when . In this way, each offer is associated with a value between 1 and 11, consistent with the choices ranging either from 0 to 22 or from 1 to 23. |

| 24. | We estimated all models with panel data regression. The analysis is consistent when we consider the twelve possible allocations or the full offer profiles for even and odd participants; nevertheless the censored regression model was more accurate for the current analysis. We ran also a multilevel analysis to account for different groups: the likelihood ratio test (testing for the multilevel model) rejects the between-group variations. Finally, we check for sessions effects: the multilevel analysis rejects between-session variation for YN and IG, while is weakly significant for UG: when wee pool results, we reject sessions variations. |

| 25. | L.Proposer is a variable equal to 1 for those participants who are actual proposer in the previous round. |

| 26. | L.Profit is a variable which measure profits earned in the previous round. |

| 27. | Odd is a variable equal to 1 for the participants and equal to zero otherwise. |

| 28. | L.Success is a variable equal to 1 if the offer is accepted in the previous round, both for proposer and responder, and 0 otherwise. Note that L.Success is equal to 0 for proposer in IG when the offer had been refused in the previous round even though this does not have an effect on the proposer’s payoffs. |

| 29. | We rely on participants for UG and participants for IG. A participant is paired with half () of the other allocator candidates, namely those of the other type (o and e) which determines the adjusted offers of this participant. Each of them is paired with the remaining other allocator candidates () which determines the acceptance threshold of responders. In total, this yields 1,260 combinations for each individual in the first round. |

| 30. | Recall that randomly selecting a proposer candidate in one pair also selects the proposer candidate of the other pair since each interacting pair involves an and an player. |

| 31. | Since YN is never played first, there is no simulation for this game type. |

| 32. | If, for instance, an o-allocator candidate does not want to offer more than necessary, e.g. in case of impunity, but would like to trigger more generosity by the e-allocator candidate, o might strategically choose and . Thus, the robust evidence of conditioning allows to manipulate the other’s actual generosity by guaranteeing when allocator candidate e (and not o) is actually endowed. For e-allocator candidates, the corresponding behavior, namely and , would be very costly: if e is actually endowed and confronts an allocator candidate o choosing , the actual offer of e would be . |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).