The Loser’s Bliss in Auctions with Price Externality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory

2.1. Setting and Theoretical Properties

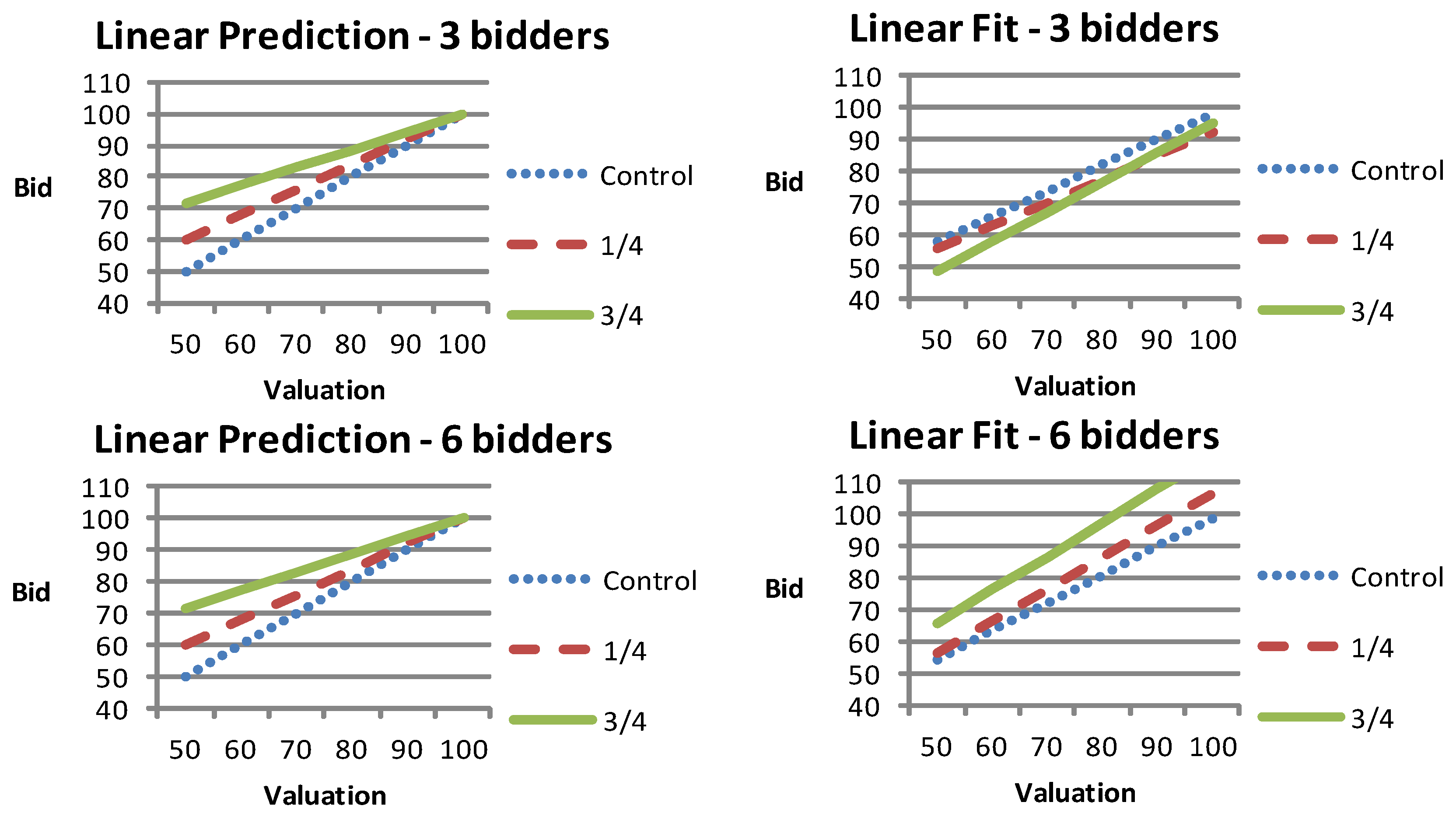

- Property 1. The bids in auctions with price externality are increasing in the multiplier (α).

- Property 2. Auctions with price externality are efficient.

- Property 3. The bids in auctions with price externality do not depend on the number of bidders (n).

2.2. Hypotheses

2.2.1. Hypothesis 1. Individual Bids and Revenues Increase in the Multiplier

2.2.2. Hypothesis 2. Auctions with Price Externality are Efficient

2.2.3. Hypothesis 3. Bidders’ WTP is Unchanging in the Number of Other Bidders

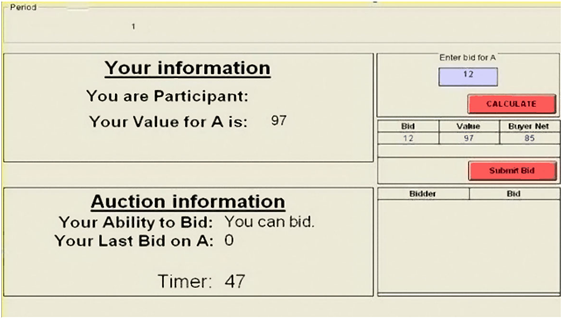

3. Experimental Design

| Multiplier | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Format | # Bidders | 0 | ¼ | ¾ |

| SPSB | 3 bidders | “3-bidder m = 0” 15 sessions | “3-bidder m = ¼” 19 sessions | “3-bidder m = ¾” 13 sessions |

| SPSB | 6 bidders | “6-bidder m = 0” 4 sessions | “6-bidder m = ¼” 6 sessions | “6-bidder m = ¾” 5 sessions |

| English | 3 bidders | “3-bidder m = 0” 13 sessions | “3-bidder m = ¼” 25 sessions | “3-bidder m = ¾” 17 sessions |

| English | 6 bidders | “6-bidder m = 0” 6 sessions | “6-bidder m = ¼” 15 sessions | “6-bidder m = ¾” Sessions |

4. Experimental Results

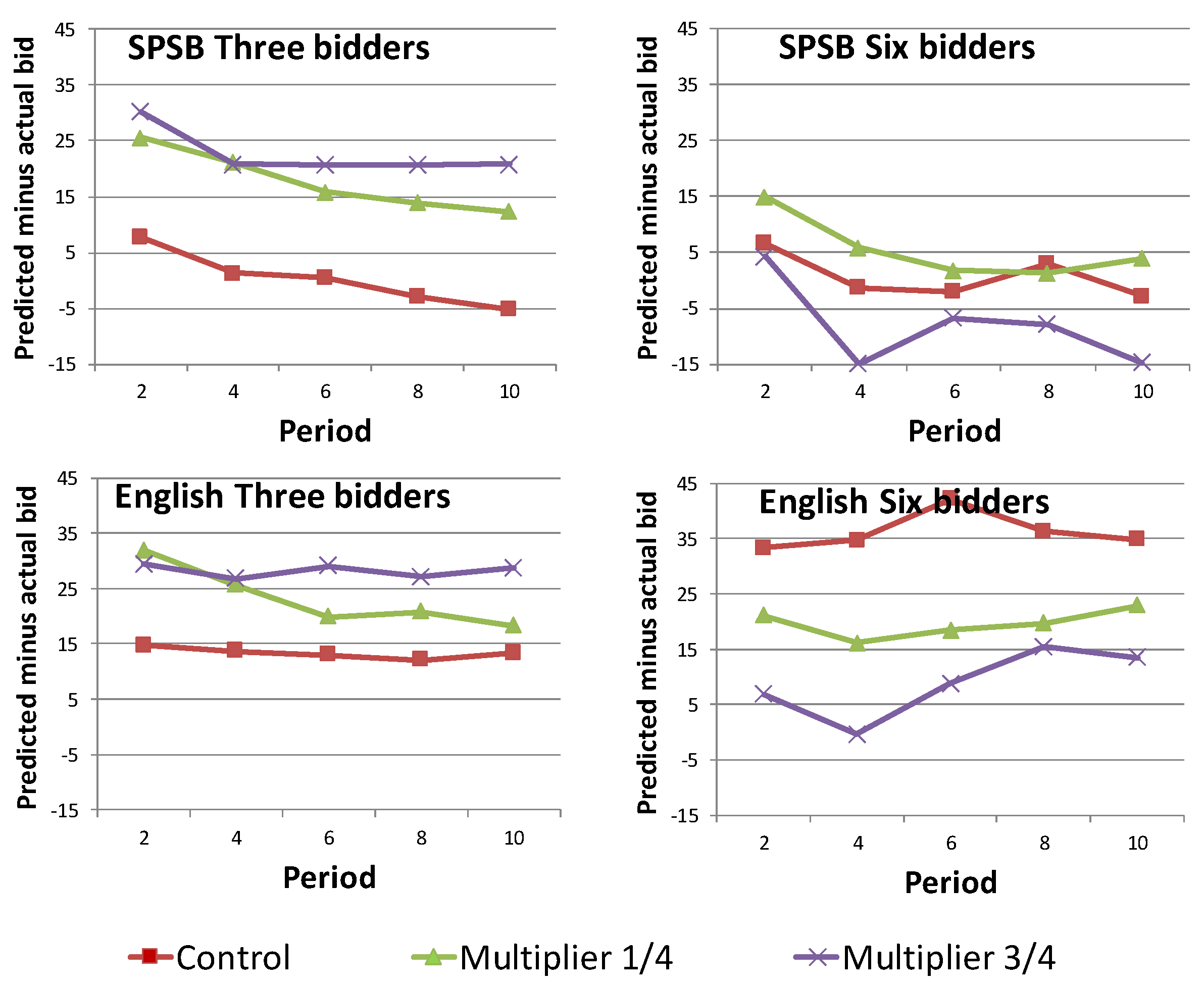

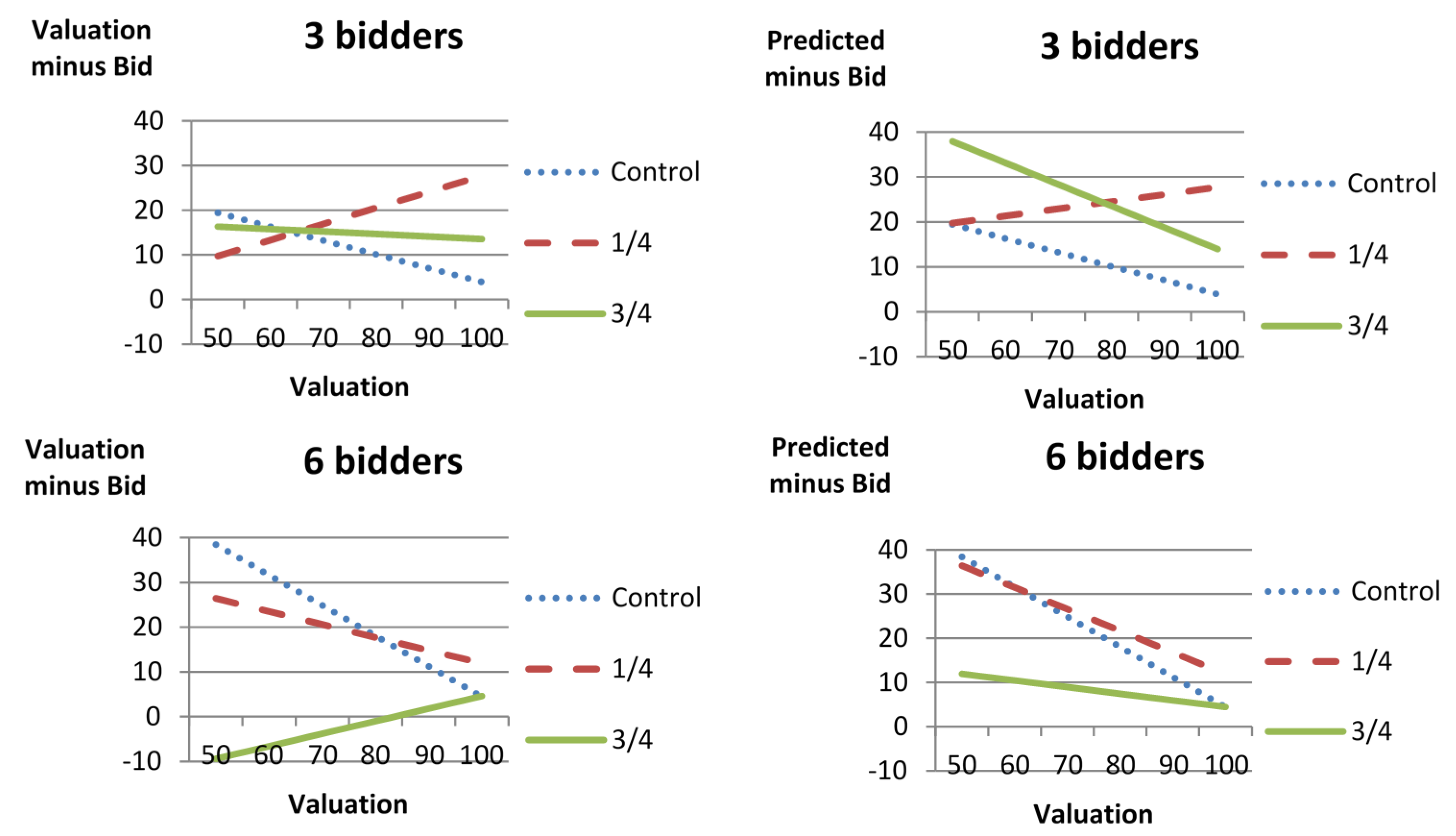

4.1. The Effect of the Multiplier on Individual Bids and Revenues

| Results SPSB Auctions | Results English Auctions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | 1. Predicted Bid Minus Bid a | 2. Valuation Minus Bid a | 3. Revenue | 4. Efficiency b | 5. Predicted Bid Minus Bid a | 6. Valuation Minus Bid a | 7. Revenue | 8. Efficiency b |

| 3-bidder, m = 0 | $−2.90 (1.43) | $−2.90 (1.43) | $93.44 (1.35) | 63.80 (5.10) | $13.24 (2.11) | $13.24 (2.11) | $75.13 (0.82) | 84.28 (4.68) |

| 3-bidder, m = ¼ | 8.45 (3.32) | 3.49 (3.32) | 95.77 (3.68) | 56.93 (4.51) | 22.60 (1.99) | 16.58 (2.02) | 71.49 (1.33) | 64.57 (3.73) |

| 3-bidder, m = ¾ | 14.66 (3.35) | 3.65 (3.29) | 90.61 (3.38) | 65.95 (4.99) | 27.75 (2.17) | 14.66 (2.16) | 78.33 (0.71) | 69.50 (4.06) |

| 6-bidder, m = 0 | 0.70 (5.30) | 0.70 (5.30) | 101.65 (3.79) | 55.00 (11.90) | 23.92 (1.36) | 23.92 (1.36) | 86.17 (1.52) | 68.33 (7.17) |

| 6-bidder, m = ¼ | 5.53 (4.79) | 0.572 (4.83) | 110.37 (7.54) | 36.67 (6.15) | 24.48 (1.29) | 19.34 (1.28) | 96.35 (0.88) | 49.33 (4.09) |

| 6-bidder, m = ¾ | −8.01 (5.09) | −18.56 (5.03) | 151.50 (14.96) | 30.00 (4.47) | 8.83 (8.90) | −2.72 (8.97) | 128.44 (20.03) | 38.75 (8.95) |

| Results SPSB Auctions | Results English Auctions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | 1. Predicted Minus Bid a | 2. Valuation Minus Bid a | 3. Revenue | 4. Efficiency b | 1. Predicted Bid Minus Bid a | 2. Valuation Minus Bid a | 3. Revenue | 4. Efficiency b |

| T-test for: 3 bidders 0 vs. ¼ | T = 2.87 p = 0.005 | T = 1.62 p = 0.109 | T = 0.54 p = 0.590 | T = 1.01 p = 0.315 | T = 2.54 p = 0.010 | T = 0.79 p = 0.180 | T = 1.70 p = 0.090 | T = 3.18 p = 0.002 |

| T-test for: 3 bidders¼ vs. ¾ | T = 1.27 p = 0.207 | T = 0.03 p = 0.974 | T = 0.98 p = 0.328 | T = 1.32 p = 0.190 | T = 1.90 p = 0.060 | T = 0.46 p = 0.650 | T = 4.08 p < 0.001 | T = 1.12 p = 0.270 |

| T-test for: 3 bidders0 vs. ¾ | T = 5.06 p < 0.001 | T = 1.91 p = 0.059 | T = 0.82 p = 0.416 | T = 0.30 p = 0.766 | T = 4.32 p < 0.001 | T = 0.42 p = 0.673 | T = 2.80 p = 0.007 | T = 2.28 p = 0.025 |

| T-test for: 6 bidders 0 vs. ¼ | T = −0.66 p = 0.527 | T = 0.02 p = 0.987 | T = 0.88 p = 0.404 | T = 1.51 p = .170 | T = 0.11 p = 0.913 | T = 0.90 p = 0.377 | T = 3.74 p = 0.001 | T = 3.14 p = 0.005 |

| T-test for: 6 bidders¼ vs. ¾ | T = 1.93 p = 0.086 | T = 2.73 p = 0.023 | T = −2.59 p = 0.029 | T = 0.84 p = 0.421 | T = 2.05 p = 0.053 | T = 2.88 p = 0.009 | T = 2.21 p = 0.038 | T = 1.31 p = 0.205 |

| T-test for: 6 bidders 0 vs. ¾ | T = 1.17 p = 0.279 | T = 2.61 p = 0.035 | T = −2.88 p = 0.024 | T = 2.15 p = 0.068 | T = 1.43 p = 0.179 | T = 2.51 p = 0.028 | T = 1.81 p = 0.096 | T = 2.75 p = 0.018 |

4.2. The Effect of the Multiplier on Auction Revenues

4.3. Efficiency in Auctions with Price Externalities

4.4. The Effect of the Number of Bidders on WTP

| H1. Individual Bids Increase in the Multiplier | H1. Revenues Increase in the Multiplier. | H2. Auctions with Price Externality are Efficient. | H3. Bidders’ WTP is Unchanging in Number of Other Bidders. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPSB–3 bidders | Not Supported | Not Supported | Not Supported (same as m = 0) | Not Supported |

| SPSB–6 bidders | Supported (only for m = ¾) | Supported (only for m = ¾) | Not Supported (same as m = 0) | |

| English–3 bidders | Not Supported | Supported (only for m = ¾) | Not Supported (less efficient then m = 0) | Supported (for ¼ multiplier) Not Supported (for ¾ multiplier) |

| English–6 bidders | Supported (only for m = ¾) | Supported | Not Supported (less efficient then m = 0) |

4.5. Analysis of Heterogeneous Population Models

| Three Bidders SPSB | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Control | One-Fourth | Three-Fourth |

| Segment 1–Alpha | 0.40 ** | 0.52 ± | 0.14 ** |

| Segment 1–Beta | 0.36 ** | 0.34 ± | 0.00 |

| Segment 2–Alpha | 0 | 0.22 ** | 0.06 ** |

| Segment 2–Beta | 0.07 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.00 |

| Segment 3–Alpha | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Segment 3–Beta | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Proportion Segment 1 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.23 |

| Proportion Segment 2 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.28 |

| Proportion Segment 3 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.49 |

| Log-Likelihood | −1739 | −2535 | −1648 |

| Six Bidders SPSB | |||

| Parameter | Control | One-Fourth | Three-Fourth |

| Segment 1–Alpha | 0.582 ** | 0 | 0 |

| Segment 1–Beta | 0 | 0.227 ** | 0.383 ** |

| Segment 2–Alpha | 0.166 ** | 0.132 ** | 0 |

| Segment 2–Beta | 0.192 ** | 0 | 0 |

| Proportion Segment 1 | 0.874 ** | 0.673 ** | 0.652 ** |

| Log-Likelihood | −1441 | −1599 | −1756 |

| Three Bidders English–Only Pivotal Bids (Second Price) Used | |||

| Parameter | Control | One-Fourth | Three-Fourth |

| Segment 1–Alpha | 0.24 ** | 1.16 ** | 0.91 ** |

| Segment 1–Beta | 0.07 | 0.81 ** | 0.70 ** |

| Segment 2–Alpha | −0.01 | 0 | −0.02 |

| Segment 2–Beta | −0.02 | 0 | 0 |

| Proportion Segment 1 | 0.62 ** | 0.71 ** | 0.70 ** |

| Log-Likelihood | −372 | −1021 | −583 |

| Six Bidders English–Only Pivotal Bids (Second Price) Used | |||

| Parameter | Control | One-Fourth | Three-Fourth |

| Segment 1–Alpha | 0.087 ** | 0 | 0 |

| Segment 1–Beta | 0 | 0.158 ** | 0.623 ** |

| Segment 2–Alpha | 0.012 ** | 0.954 ** | 0 |

| Segment 2–Beta | 0 | 0.949 ** | 0.151 ** |

| Proportion Segment 1 | 0.75 ** | 0.87 ** | 0.82 ** |

| Log-Likelihood | −117 | −521 | −681 |

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Derivation and Proofs

Appendix B. Experiment Instructions

Instructions for Research Study

References

- Steitzer, S. Online School Auctions Curtail Hassles but Also the Socializing. Available online: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB1020806782944385080 (accessed on 12 February 2014).

- Navarro, P. Why do corporations give to charity? J. Bus. 1988, 61, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, P.R.; Menon, A. Cause-related marketing: A coalignment of marketing strategy and corporate philanthropy. J. Market. 1988, 52, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.R.; Drumwright, M.E.; Braig, B.M. The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. J. Market. 2004, 68, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Market. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahilevitz, M.; Myers, J.G. Donations to charity as purchase incentives: How well they work may depend on what you are trying to sell. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracejus, J.W.; Olsen, G.D.; Brown, N.R. On the prevalence and impact of vague quantifiers in the advertising of cause-related marketing (CRM). J. Advert. 2003, 32, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelman, J.M.; Arnold, S.J. The role of marketing actions with a social dimension: Appeals to the institutional environment. J. Market. 1999, 63, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Market. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Market. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht-Wiggans, R. Auctions with price-proportional benefits to bidders. Games Econ. Behav. 1994, 6, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.M.; Pevnitskaya, S.; Salmon, T.C. Do preferences for charitable giving help auctioneers? Exp. Econ. 2010, 13, 14–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, T.C.; Isaac, R.M. Revenue from the saints, the showoffs and the predators: Comparisons of auctions with price-preference values. Res. Exp. Econ. 2006, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Engers, M.; McManus, B. Auctions with price externality. Int. Econ. Rev. 2007, 48, 953–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, V.; Rapoport, A.; Seale, D. Sequential search by groups with rank-dependent payoffs: An experimental study. Org. Behav. Hum. Dec. Processes 2014, 124, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkowski Leszczyc, P.T.; Pracejus, J.W.; Shen, Y. Why more can be less: An inference-based explanation for hyper-subadditivity in bundle valuation. Org. Behav. Hum. Dec. Processes 2008, 105, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U.M.; Basuroy, S.; Soltysinski, K. Auction or agent (or both)? A study of moderators of the herding bias in digital auctions. Int. J. Res. Market. 2002, 19, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariely, D.; Simonson, I. Buying, bidding, playing, or competing? Value assessment and decision dynamics in online auctions. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyman, J.E.; Orhun, Y.; Ariely, D. Auction fever: The effect of opponents and quasi-endowment on product valuations. J. Interact. Market. 2004, 18, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruvy, E.; Popkowski Leszczyc, P.T. Bidder motives in cause-related auctions. Int. J. Res. Market. 2009, 26, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkowski Leszczyc, T.L.; Rothkopf, M.H. Charitable motives and bidding in auctions with price externality. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.M.; Tor, A. The N-effect: More competitors, less competition. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischbacher, U. z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithammer, R.; Adams, C. The sealed-bid abstraction in online auctions. Market. Sci. 2010, 29, 964–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortaçsu, A.; Nielsen, E.R. Commentary—Do bids equal values on eBay? Market. Sci. 2010, 29, 994–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K.; Wang, X. Commentary: Bidders’ experience and learning in online auctions: Issues and implications. Market. Sci. 2010, 29, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, P.; Murnighan, J.K. Learning to avoid the winner’s curse. Org. Behav. Hum. Dec. Processes 1996, 67, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.B.; Bazerman, M.H.; Carroll, J.S. An evaluation of learning in the bilateral winner’s curse. Org. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 48, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. Giving with impure altruism: Applications to charity and Ricardian equivalence. J. Polit. Econ. 1989, 97, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. Econ. J. 1990, 100, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A.; Eshed-Levy, D. Provision of step-level public goods: Effects of greed and fear of being gypped. Org. Behav. Hum. Dec. Processes 1989, 44, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.M.; Walker, J.M. Group size effects in public goods provision: The voluntary contribution mechanism. Quart. J. Econ. 1988, 53, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, V.; Rapoport, A. The price of anarchy in social dilemmas: Traditional research paradigms and new network applications. Org. Behav. Hum. Dec. Processes 2013, 120, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfenbein, D.W.; McManus, B. A greater price for a greater good? Evidence that consumers pay more for charity-linked products. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2010, 2, 28–60. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, J.; Holmes, J.; Matthews, P.H. Auctions with price externality: A field experiment. Econ. J. 2008, 118, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeree, J.K.; Maasland, E.; Onderstal, S.; Turner, J.L. How (not) to raise money. J. Polit. Econ. 2005, 113, 897–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A.; Rajan, U. Cause marketing: Spillover effects of cause-related products in a product portfolio. Manag. Sci. 2009, 55, 1469–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazer, A.; Konrad, K.A. A signaling explanation for charity. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 10, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, R.; Yildirim, H. Why charities announce donations: A positive perspective. J. Public Econ. 2001, 81, 423–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Meier, S. Social comparisons and pro-social behavior: Testing “conditional cooperation” in a field experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 1717–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.M.; Salmon, T.C.; Zillante, A. An experimental test of alternative models of bidding in ascending auctions. Int. J. Game Theory 2005, 33, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1 There is a growing body of research in marketing that has concluded that linking product purchases with donations to charities has a positive impact on perceptions [4,5,6,7]. However, these positive effects are not universal, since several researchers have shown that in certain instances it may lead to a reduction in purchase intention [8,9,10].

- 2 Isaac et al. (2010) [12] encountered a hint of this effect in second price sealed bid auctions. They found that charitable preferences of the type investigated here do not significantly increase individual bids or auction revenues, thus identifying a puzzle. In their carefully designed second price sealed bid experiment, four decision makers played 40 auction rounds with multipliers of 0 in a benchmark condition, 0.15 in a low bonus condition or 0.50 in a high bonus condition (different decision makers in each condition). From their plots, bids in the 0.5 multiplier (second price basic charity) condition are on average lower than theoretical predictions, and this gap is quite substantial.

- 3 The intent was to calibrate earnings to be roughly the same for different sessions—in the $15 range per subject including a show up fee. We varied the exchange rate within treatments to test for exchange rate effect. No exchange rate effect was found.

- 4 Note that revenue (equal to the winning price) in condition m = ¾ with 6 bidders is significantly above the maximum bidder valuation of 100, which is nevertheless below the theoretical prediction for this condition.

- 5 Some underbidding in the control treatment is expected. The predicted bid for a losing bidder is at one’s valuation. Any bid above one’s valuation in the zero-multiplier condition results in a loss conditional on winning regardless of bidding strategy or beliefs. So any bidder deviation from prediction should be below the predicted bid. Deviations could be due to any number of reasons including bidders bidding intermittently, jump bidding, or simply truncated errors.

- 6 Foreman and Murnighan (1996) [27] investigated whether feedback and relevant experience over four weeks could help alleviate overbidding in common value auctions (known as the winner’s curse). They found that while some learning occurred, the overbidding was remarkably persistent over time.

- 8 Elsewhere in this literature, theoretical predictions do not seem to hold very well. For example, [35] report the results of four sealed bid auctions with price externality for four different preschools, comparing revenues of a first price, second price and all-pay auctions. In contrast to the theoretical work [35,36], they find that first price auctions revenues are highest followed by second price and finally all-pay auctions. They attribute this discrepancy to endogenous bidder participation.

- 9 This observation could imply predictions in either direction—depending on whether individuals are altruistic towards the charities or towards other bidders. It is reasonable to assume that when bidding in auctions with price externality auctions with price externality, the bidder’s altruism towards the charity dominates.

- 10 There might also be an added small bid increment which is conveniently ignored here.

- 11 In other words, there is no additional utility per se from being the price setter.

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haruvy, E.; Popkowski Leszczyc, P.T.L. The Loser’s Bliss in Auctions with Price Externality. Games 2015, 6, 191-213. https://doi.org/10.3390/g6030191

Haruvy E, Popkowski Leszczyc PTL. The Loser’s Bliss in Auctions with Price Externality. Games. 2015; 6(3):191-213. https://doi.org/10.3390/g6030191

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaruvy, Ernan, and Peter T. L. Popkowski Leszczyc. 2015. "The Loser’s Bliss in Auctions with Price Externality" Games 6, no. 3: 191-213. https://doi.org/10.3390/g6030191

APA StyleHaruvy, E., & Popkowski Leszczyc, P. T. L. (2015). The Loser’s Bliss in Auctions with Price Externality. Games, 6(3), 191-213. https://doi.org/10.3390/g6030191