Abstract

We conduct an artefactual field experiment to compare the individual preferences and propensity to cooperate of three pools of subjects: Undergraduate students, temporary workers and permanent workers. We find that students are more selfish and contribute less than workers. Temporary and permanent contract workers have similar other-regarding preferences and display analogous contribution patterns in an anonymous Public Good Game.

JEL Classification:

C72; C93; D23; H41; J54

1. Introduction

Undergraduate university students can be easily recruited for experiments and are the typical object of inquiry in the experimental social sciences. One critical issue linked to this admittedly specific population concerns whether the experimental results obtained with students are robust to using other populations, such as workers or older age people [1,2,3,4]. To address this issue, the literature has compared the behavior of undergraduate students with different types of workers, such as nurses [5], Chief Executive Officers [6], workers in a publishing distribution warehouse [7], bicycle messengers [8], and clerical workers [9].

Our paper relates to this stream of research and it investigates, using an artefactual field experiment [10] and a sample of subjects living in an Italian region with high social capital, whether and to what extent the other-regarding preferences and cooperative behavior of undergraduate university students differ from those of workers, and how these preferences translate into behavior in a strategic setting. We further study whether there exists a link between the type of worker’s contractual arrangement (temporary or permanent contract) and her social preferences and behavior. The answer to the latter question is still an open issue which has not been fully addressed so far. Yet, this line of inquiry deserves investigation, due to the rapid diffusion of temporary employment (i.e., a work situation where an employee is hired for a pre-determined time limit) in many industrialized countries, in particular in countries providing high levels of employment protection [11].

From a firm’s perspective, temporary employment reflects the need for a flexible labor demand which can be quickly adjusted to workload fluctuations. It also makes it easier for a firm to replace less productive people with more productive ones, and may as well favor the inflow of innovative ideas. This type of contractual arrangement can however also have negative effects. A high turnover may in fact hinder social cohesion, cooperative spirit, organizational commitment and trust in the workplace, and increase the probability of opportunistic behavior [12]. In addition, workers who compete in the labor market for short-term positions compete more often with other workers for a job, and they may therefore display a more competitive attitude. All these factors can lead to substantial economic costs and inefficiencies which may cancel out the benefits of a flexible labor demand.

Since the propensity to cooperate and the other-regarding preferences of permanent workers may vary substantially, depending on the type of firm and the business culture of a company, we selected a benchmark which we expected to be associated with the highest propensity to cooperation and level of pro-sociality. Accordingly, we recruited permanent workers of a co-operative (co-op). 1 The importance of cooperation is one of the distinctive features of a co-op, together with the importance given to the values of self-help, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity and solidarity. Hence, one would expect co-op permanent workers to be particularly prone to cooperation (see, e.g., [8]), with significant and sizeable differences with respect to non-co-op workers, in particular temporary workers who are not members of a co-op. A priori, this makes the sample of permanent co-op workers a reasonable upper-bound benchmark to be compared with the preferences and behavior of the other two samples. Students, instead, are expected to be the lower bound benchmark for the propensity to cooperate and the other-regarding preferences of temporary and permanent workers, as documented in the experimental literature showing that students are in general less prosocial than non-students (e.g., [6,8,13,14]).

In our experiment, subjects played a Dictator Game, a Decomposed Game and a Public Good Game. These are standard tasks used in the experimental literature to investigate other-regarding preferences and cooperative behavior.

Our results on the behavior of undergraduate students are similar to those reported in the literature with similar subject pools (e.g., [5,8,15,16,17,18]). Temporary workers, instead, are significantly more cooperative and less opportunistic. In addition, they are also more other-regarding than students and their behavior and preferences are very much similar to those of co-op permanent workers. This result is notable as temporary workers did not know each other, and they shared very little common experiences, either in terms of education, training on the job or specialization. Moreover, the probability of meeting again in subsequent occasions was small, which makes reputation a rather weak argument for inducing cooperation in a repeated interaction perspective. On the contrary, permanent workers knew each other and interacted together on a daily basis in the same workplace. 2 In addition, they worked for the same co-operative, and were constantly exposed to the values of the institution they worked for.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper which, in addition to the comparison between students and workers, also applies the experimental methodology to investigate preferences and propensity to cooperate of temporary and permanent workers. 3 This paper provides complementary evidence to the literature studying workers’ effort provision in a real work environment (e.g., [24,25]) and to more traditional sources of information, such as those based on surveys and questionnaires (e.g., [26,27]). In particular, we obtain information on the preferences and propensity to cooperate of co-op workers, on which previous experimental investigation is surprisingly scarce. A noteworthy exception is Burks et al. [8], who provide field experimental evidence that employees at firms that pay for performance are significantly less cooperative than those who are members of cooperatives. The comparison between temporary and permanent (co-op) workers is a useful starting point to understand whether these differences are driven by a different propensity to cooperate of workers in general, and whether the possible differences in preferences and behavior may be linked to the specific type of contractual arrangement.

2. The Subject Pools

The subjects taking part in the experiment were recruited from three different populations: undergraduate students of the University of Bologna, temporary employees and permanent employees.

Students. We recruited 96 undergraduate students with an Economics major from the Forlì Campus of the University of Bologna, using the subject pools maintained through ORSEE [28].

Temporary workers. The pool of temporary workers that participated to the experiment was supplied by Obiettivo Lavoro (OL), a large recruitment agency that operates mainly in Italy, with branches operating also in Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Poland, Romania, Paraguay and Peru. OL operates in sectors such as health care and social assistance, cleaning and logistics, construction, large scale retail, hotel, catering, and tourism, with yearly total revenue of 308 million euros (operating revenue in 2012). It manages more than 1,400,000 profiles of workers to be hired to firms or institutions demanding labor force. Originally established as a co-operative company in 1997, OL was converted into a public limited company in 2003. It has adopted an Ethics Code and in 2007 it obtained the SA8000 certification for its Corporate Responsibility practices. 4 The 72 subjects which OL supplied for the experiment were temporary workers who had never participated in an economic experiment like ours, nor ever had relations with OL before 2003.

Permanent workers. The pool of cooperative members that took part in the experiment was supplied by Formula Servizi (FS), a workers co-operative company founded in 1975, which operates in five Italian regions (mainly in Emilia Romagna, where 75% of its revenue is raised). It supplies several services, mainly in sectors such as cleaning, catering, maintenance and logistics, with a yearly total revenue of 55 million euros (operating revenue in 2012). FS has obtained the SA8000 certification for its Corporate Responsibility practices in 2003, and has adopted an Ethical Code in 2012. The total number of workers in 2012 is 1892, with a prevalence of women (83%) and an average age of 47 years. Among these workers, 892 are members of the cooperative (“soci”), 890 are employees, while 110 are outsourced workers. For our experiment, we recruited 84 subjects only among cooperative members, therefore choosing to focus on the most “permanent” set of workers, and we excluded both employees and outsourced staff. None of the permanent workers had participated in economic experiments before.

The details about the socio-demographic characteristics (collected in a questionnaire at the end of the experiment) of the three subject pools are in the Appendix. Students differ in many dimensions compared to both permanent and temporary workers. Most notably, students are younger, less religious, less likely to be married, with a higher education and characterized by a smaller proportion of women. There are also a few differences between permanent and temporary workers. In particular, permanent workers are older, more likely to be married, more likely to be Christian, and with more years of work experience than temporary workers. In all the other dimensions, we do not detect any statistically significant difference between temporary and permanent workers. Because of these differences between our subject pools, we will also control in the data analysis for the socio-demographic characteristics of subjects (especially, those which were significantly different across the three samples) in order to ensure that our results are not due to differences between the characteristics of the three populations. 5

3. Experimental Design

The experiment is composed of two stages: A classification stage and a main stage. In the classification stage, subjects are required to perform three tasks which are widely employed in the experimental literature to study other-regarding preferences. The subjects first play a one-shot Dictator Game, then they play a Public Good Game to assess their conditional willingness to contribute to a public good (Strategy Method) and finally they play a Decomposed Game. In the main stage, subjects play a repeated anonymous linear Public Good Game (12 repetitions). The experiment was incentivized and fully computerized with the software z-Tree [29]. Anonymity was guaranteed both during the game and the payment procedures.

In the one-shot Dictator Game, each subject is randomly matched with another individual, and has to decide how to divide an endowment of 300 experimental tokens between herself and her matched subject. After each subject has made her decision, a random mechanism establishes whether her proposal or the proposal of the counterpart is implemented. This game provides a measure of fair behavior for each participant. Subjects who give less than 100 tokens are classified as self-centered, while those who give 100 or more are classified as beneficent (for a similar classification, see [17]).

In the second task, subjects are classified according to their behavior in a linear one-shot Public Good Game using the Strategy Method Technique [30,31]. Subjects are randomly allocated to groups of four individuals. An endowment of 200 tokens is to be allocated by each subject between a “private” and a “public” account. The individual payoff is determined according to the following function:

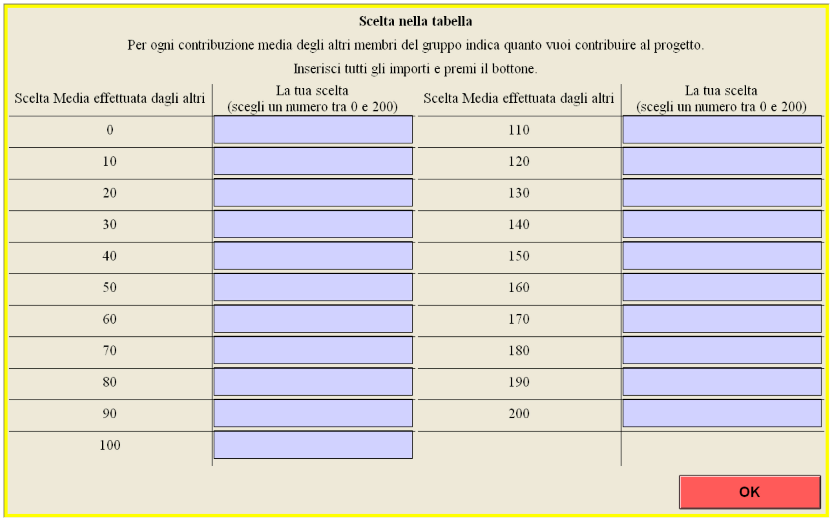

where is player i’s contribution to the public account and the contribution by the other members of the group. Since the contributions of the group to the public account are doubled and equally divided among the group participants, the marginal individual benefit from contributing to the public good is 0.5. Subjects are first asked to make an unconditional contribution to the public good, and then to indicate their willingness to contribute to the public account, conditional upon different possible contributions of the other group members. The possible average contributions range from 0–200, and are listed as multiples of 10 tokens. After the choices are made, one subject per each group is randomly selected and paid according to her conditional contribution to the unconditional contributions of the other three members. The remaining players are paid according to their unconditional contributions. This task provides a measure of subjects’ cooperativeness.

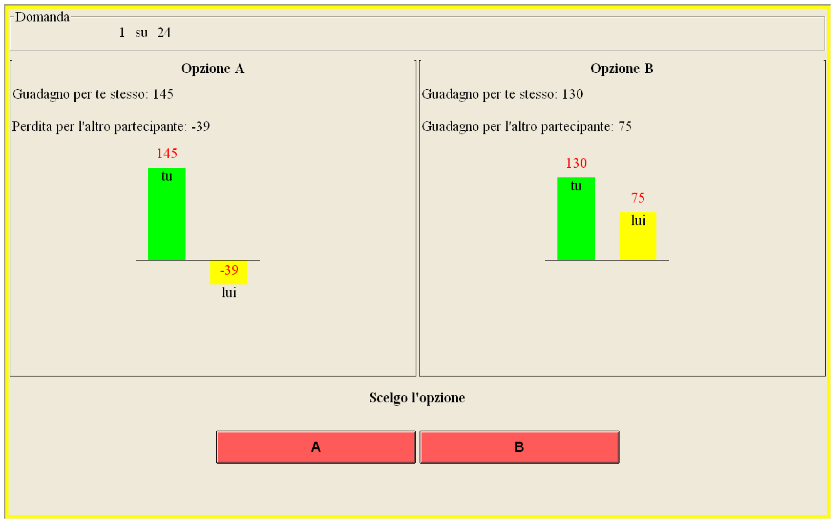

In the third classification task, we employ a Decomposed Game Technique, a classificatory task used both in the economic and psychological literature to study the distributional preferences of subjects (e.g., [17,18,31,32,33]). Participants are asked to choose between two possible allocations of money. For example, a subject must choose whether she prefers an allocation where she receives 130 tokens and the other participant receives 75 tokens, or an allocation where she receives 145 tokens and the other participants loses 39 tokens. Subjects are randomly and anonymously matched in couples and asked to make 24 choices between pairs of allocations. The individual earnings are equal to the sum of the payoffs of the 24 choices made by the subject and by her co-participant, who remains the same throughout the 24 choices (for more details, see [17,18,31]).

No feedback about the co-participants’ choices is provided to the subjects during the classification stage: The subjects only receive information about their earnings at the end of the experiment. In addition, the order of the classification tasks is the same for all the subjects, and, therefore, it cannot explain possible across-sample differences.

After the classification stage, the subjects enter the main stage of the experiment and play a repeated linear 4-player Public Good Game (12 rounds). At the beginning of the first round, subjects are randomly matched in groups of four which remain the same over all rounds. The payoff function is identical to the one used in the Strategy Method, except for the individual endowment (20 tokens instead of 200 tokens). At the end of each round, each subject receives feedback about her contribution to the group account, the single contributions of the other members (whose identities are hidden), 6 and her total earnings. Comprehension and familiarity with the experimental setup is obtained by requiring subjects to enter three forced inputs. 7 After the first 12 rounds, the subjects engage in additional experimental tasks which we do not consider in this paper. 8 After all tasks are completed, subjects are informed about their earnings and are required to complete a demographic questionnaire (reported in the Appendix).

The experiment was conducted at the LES (Laboratorio di Economia Sperimentale, Forlì campus of the University of Bologna, Italy) and at the BLESS (Bologna Laboratory for Experiments in Social Science, Bologna campus of the University of Bologna, Italy) in the period July 2009–January 2011 (details about dates and places of each session are in the Appendix). We ran a total of 18 sessions, with either 12 or 24 subjects per session. Each session was composed by homogeneous subject pools, for a total of 72 temporary workers, 84 permanent workers and 96 students, none of which had previously participated in a similar experiment. No subject could participate in more than one session. The participants were randomly assigned to computer terminals, which were separated by partitions in order to avoid facial or verbal communication between subjects. Before proceeding with each task, subjects filled in a control questionnaire designed to check their understanding of the instructions. Clarifications were individually given to subjects who answered incorrectly. The experiment used a fictional currency, with one token being equal to one euro cent. The exchange rate was not differentiated among the three pools. 9 At the end of the experiment, subjects were paid for all tasks, on top of a show-up fee of €2. On average, subjects earned €20.93 (approximately 28 US dollars). To secure anonymity in the lab, assistants paid the participants privately at their desks. Each session lasted on average 2 h, including instructions and check questions to verify the understanding of the rules by the participants. The experimental instructions were as neutral as possible, and made available both on screen and on paper at the beginning of each experimental task. To ensure common knowledge, instructions were also read out aloud by the experimenter.

4. Results

In this section, we report the results of the classification tasks (Dictator Game, Public Good Game with Strategy Method and Decomposed Game Technique) and of the repeated linear Public Good Game. 10

4.1. Dictator Game

Following [17], we classify subjects as beneficent when they donate one third or more of their endowment to the other player, and we classify them as self-centered otherwise. The results are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Beneficent and self-centered subjects in the Dictator Game.

| Temporary | Permanent | Student | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 72 | 84 | 96 | 252 |

| Average offer | 40% (121) | 45% (135) | 23% (70) | 35% (106) |

| Self-centered | 25% (n = 18) | 14.3% (n = 12) | 55.2% (n = 53) | 32.9% (n = 83) |

| Beneficent | 75% (n = 54) | 85.7% (n = 72) | 44.8% (n = 43) | 67.1% (n = 169) |

We can reject the hypothesis that being beneficent is independent of whether a subject is a temporary worker, a permanent worker or a student (Chi-squared test, p < 0.001). 11 The proportion of beneficent subjects among temporary and permanent workers is significantly larger than among students (Chi-squared test, p < 0.001). In comparison with the literature, note that the share of beneficent subjects among our undergraduate students is lower than the one found in [17], where the majority of subjects (61%, i.e., 43 out of 71) was classified as beneficent. However, the average offer by students is in line with the literature (see, e.g., [35]). Although beneficent subjects are more common among the permanent workers than among the temporary workers, the difference is only weakly significant (Chi-squared test, p = 0.091) and disappears once we control for other covariates (see next paragraph on the regression analysis). 12 This allows stating the following:

Result 1: In the Dictator Game student are less beneficent than workers. Temporary and permanent workers do not differ.

Table 2 reports the results from the regression analysis. Regression 1 is a Tobit regression where the dependent variable is the amount offered in the Dictator Game; Regression 2 is a Probit regression on the likelihood of being a beneficent subject. In both regressions the explanatory variables include age and dummies identifying the experimental sample (using temporary workers as baseline category), gender (Male = 1 for male subjects), marital status (Married = 1 for married subjects), religious affiliation (NoReligion = 1 for atheist or agnostic subjects), and educational background (Degree = 1 for subjects with a university degree). 13

Table 2.

Regression analysis (Dictator Game).

| Regression 1 | Regression 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Std. Err. | p > z | dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | |

| Student | −53.557 *** | 12.35 | 0 | −0.181 *** | 0.06 | 0.005 |

| Permanent | 3.082 | 15.77 | 0.845 | 0.037 | 0.09 | 0.684 |

| Male | 4.264 | 11.3 | 0.706 | −0.020 | 0.06 | 0.725 |

| Married | 5.092 | 12.75 | 0.69 | 0.028 | 0.09 | 0.748 |

| NoReligion | −21.08 | 12.99 | 0.106 | −0.059 | 0.07 | 0.379 |

| Degree | 10.108 | 11.08 | 0.363 | 0.042 | 0.06 | 0.478 |

| Age | 0.945 | 0.64 | 0.144 | 0.009 ** | 0.00 | 0.031 |

| Constant | 86.641 *** | 22.18 | 0 | |||

| Obs | 252 | 252 | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.021 a | 0.141 | ||||

| Prob > F | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

Notes: Regression 1: Tobit regression with robust standard errors, the dependent variable is the offer in the Dictator Game; Regression 2: Probit regression with robust standard errors on the likelihood of being a beneficent (in the table, we report the average marginal effects of the independent variables). a This is the McFadden’s pseudo R-squared. Obs = observations. Prob > F = p-value of F-test. dy/dx = marginal effects. ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

We detect a significant effect of age in Regression 2. In particular, older subjects are more likely to be beneficent than younger. Once we control for the individual characteristics, the regression analysis is consistent with Result 1.

4.2. Public Good Game with Strategy Method

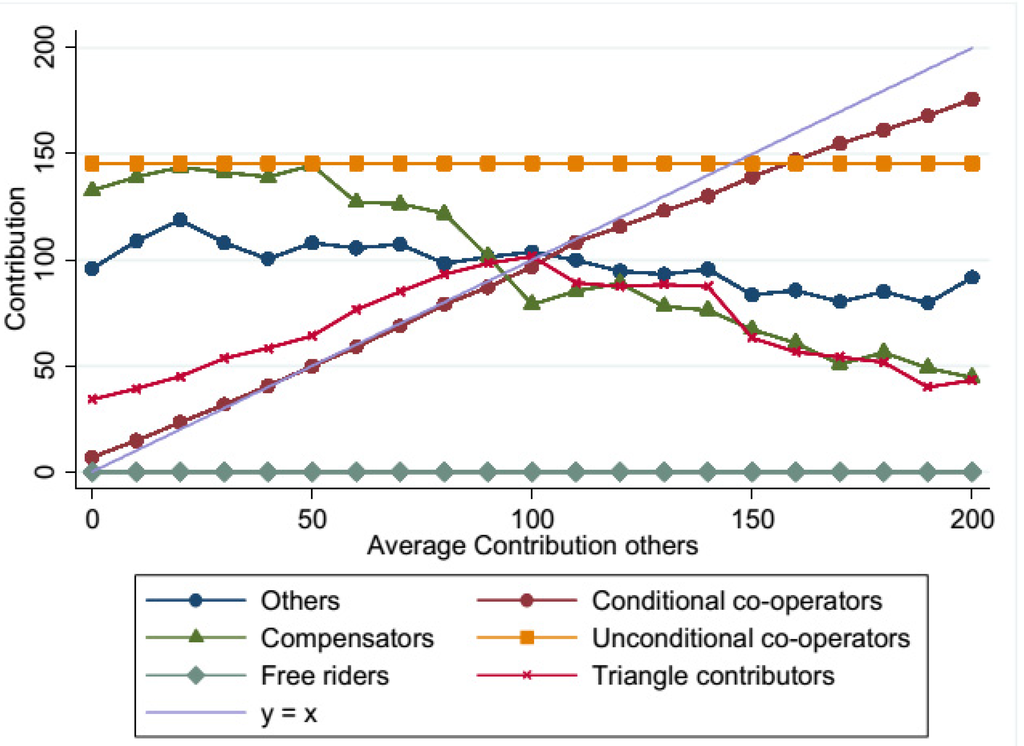

Using the Strategy Method, subjects are classified in six categories depending on their conditional contributions in the Public Good Game. Similar to [30] we classify as Conditional Cooperators those subjects that display a significant monotonically increasing pattern between their conditional contribution and the average contribution of the other group members (Spearman rank correlation ρ > 0, p < 0.01); as Free Riders those who always contribute zero, and as Triangle contributors those who display a significant monotonically increasing pattern up to a maximum (Spearman ρ > 0, p < 0.01) and a significant monotonically decreasing pattern after that maximum (Spearman ρ < 0, p < 0.01). We also add two categories. Subjects who contribute a positive amount irrespective of the others’ contributions are classified as Unconditional Cooperators, whereas subjects who display a significant monotonically decreasing pattern (Spearman ρ < 0, p < 0.01) are classified as Compensators, as they seem to counterbalance low contributions by the others. All remaining subjects are pooled in a residual category called Others. In Figure 1, we report the average contribution of each type of subject, conditional on the average contribution of the other group members.

Figure 1.

Average contribution (Strategy method), all subjects (n = 252).

Table 3 shows the frequencies of the different types of subjects in the three samples and in the whole data set.

We find that the share of conditional cooperators is the largest in all the three samples, which suggests a general tendency to reciprocate and to conform to the choices of the other group members. When considering students, however, some differences deserve to be mentioned. The share of conditional cooperators among students is significantly higher than among permanent workers (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.029). Moreover, the share of unconditional cooperators is the lowest among students (p = 0.040 when comparing with the permanent workers, and p = 0.012 with the temporary workers). 14 The finding that conditional cooperators are the largest share of the sample is consistent with [30], in which they report 50% of the sample (n = 44) to be conditionally cooperative, which is admittedly much lower than the results reported in Table 3. In our experiments, the remaining categories do not cover large shares of the population; in contrast Fischbacher et al. [30] find that 30% of their subjects behave as a free rider and 14% is a “triangular” subject (called “hump shaped” in their paper). A possible reason for these discrepancies may be due to the different payoff function, and in particular, to a public good multiplier equal to 0.4, instead of 0.5 as in our design.

Table 3.

Classification of types in the three samples (Strategy method).

| Type | Temporary | Permanent | Student | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional cooperator | 70.8% (n = 51) | 64.3% (n = 54) | 78.1% (n = 75) | 71.4% (n = 180) |

| Unconditional cooperator | 9.7% (n = 7) | 7.1% (n = 6) | 1.0% (n = 1) | 5.6% (n = 14) |

| Free rider | 1.4% (n = 1) | 3.6% (n = 3) | 5.2% (n = 5) | 3.6% (n = 9) |

| Triangular | 1.4% (n = 1) | 3.6% (n = 3) | 2.1% (n = 2) | 2.4% (n = 6) |

| Compensator | 5.6% (n = 4) | 5.9% (n = 5) | 2.1% (n = 2) | 4.4% (n = 11) |

| Others | 11.1% (n = 8) | 15.5% (n = 13) | 11.5% (n = 11) | 12.7% (n = 32) |

| Total | 100% (n = 72) | 100% (n = 84) | 100% (n = 96) | 100% (n = 252) |

A priori we expected permanent workers to display a larger share of cooperators (either conditional or unconditional) with respect to temporary workers. Interestingly, this is not the case as the share of cooperators is not statistically different between the two samples of workers (p > 0.1).

Table 4.

Multinomial logit (Strategy method).

| Compensator | Conditional | Free Rider | Triangular | Unconditional | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | |

| Student | −0.021 | 0.04 | 0.554 | 0.091 | 0.09 | 0.292 | 0.010 | 0.03 | 0.768 | 0.005 | 0.03 | 0.878 | −0.109 * | 0.06 | 0.077 |

| Permanent | −0.022 | 0.03 | 0.499 | −0.113 | 0.08 | 0.165 | 0.099 ** | 0.05 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.03 | 0.287 | −0.020 | 0.04 | 0.636 |

| Male | −0.006 | 0.02 | 0.797 | −0.051 | 0.06 | 0.386 | 0.015 | 0.02 | 0.542 | 0.020 | 0.02 | 0.396 | 0.010 | 0.03 | 0.748 |

| Married | 0.065 * | 0.03 | 0.051 | 0.341 *** | 0.12 | 0.005 | −0.388 *** | 0.12 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.02 | 0.352 | −0.030 | 0.03 | 0.357 |

| NoReligion | 0.009 | 0.03 | 0.772 | 0.055 | 0.07 | 0.460 | 0.026 | 0.03 | 0.335 | −0.011 | 0.02 | 0.666 | −0.007 | 0.04 | 0.854 |

| Degree | −0.016 | 0.04 | 0.644 | −0.031 | 0.07 | 0.657 | 0.010 | 0.03 | 0.721 | 0.033 | 0.03 | 0.269 | −0.045 | 0.04 | 0.264 |

| Age | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.902 | 0.003 | 0.00 | 0.509 | −0.008 ** | 0.00 | 0.019 | −0.000 | 0.00 | 0.964 | 0.001 | 0.00 | 0.540 |

| Obs | 252 | ||||||||||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.088 | ||||||||||||||

| Prob > F | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

Note: Multinomial logit regression with robust standard errors. The table reports the average marginal effects of the independent variables for each category of the dependent variable. Obs = observations. Prob > F = p-value of F-test. dy/dx = marginal effects. * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Result 2: The shares of conditional and unconditional cooperators do not differ among temporary and permanent workers.

We also ran a multinomial logit regression where the dependent variable is the strategy method classification and where we control for the socio-demographic characteristics of the subjects. 15 For certain categories the sample size is very small, and, therefore, the results should be taken with care. In Table 4, we report the average marginal effects of the independent variables for each classification category. Compared to temporary workers, students are less likely to be unconditional co-operators, while permanent workers are more likely to be free riders. Interestingly, married people are more likely to be conditional cooperators and less likely to be free riders. Consistent with the literature, we also detect an effect of age whereby older subjects are less likely to be free-riders, although the effect is small in magnitude.

4.3. Decomposed Game Technique

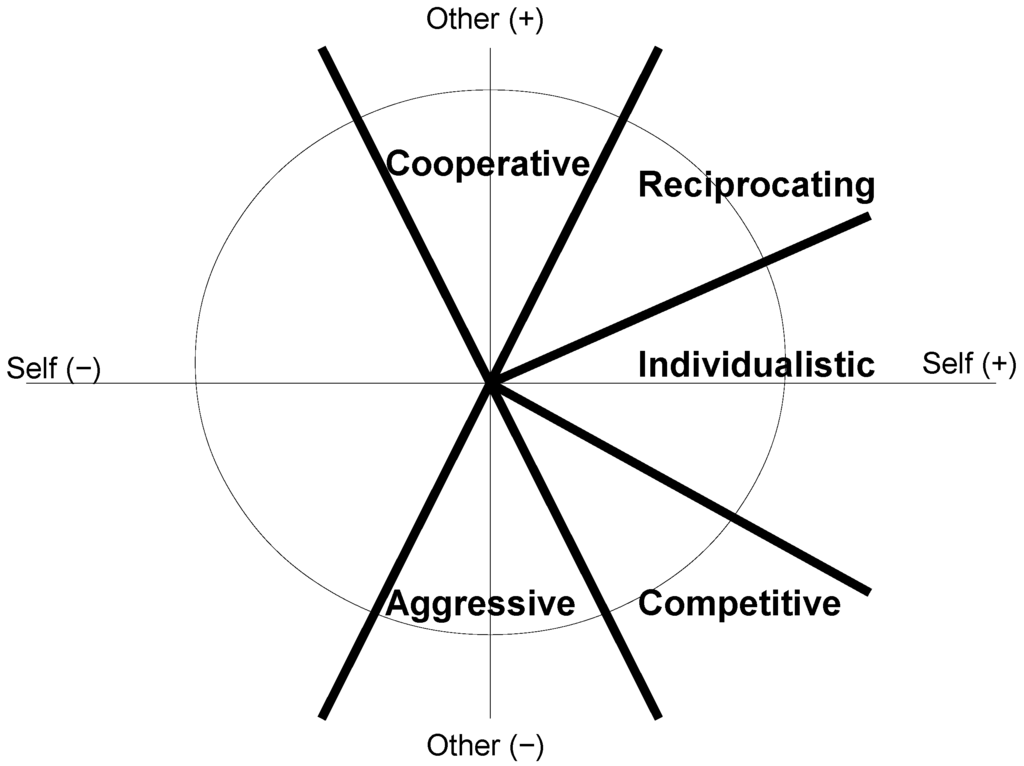

The Decomposed Game Technique allows classifying subjects in five categories (Aggressive, Competitive, Individualistic, Reciprocating and Cooperative) depending on their choices across 24 pairs of allocations. To classify subjects, we consider the total amount of tokens x each person allocated to herself in the 24 choices, and the total amount of tokens y she allocated to her partner. The classification depends on a measure, called the motivational vector that is calculated as the inverse tangent of the ratio y/x (see [36,37]). Geometrically, this measure represents the slope of the line passing for the origin and the point (x, y). Subjects are classified as Aggressive if the motivational vector has a slope between −112.5 and −67.5 degrees, Competitive if it is between −67.5 and −22.5, Individualistic if between −22.5 and 22.5, Reciprocating if between 22.5 and 67.5, and Cooperative if between 67.5 and 112.5. Finally, subjects are classified as Others if the length of their vector is less than 75 (see [17,18]). 16

The results of this classification are reported in Table 5. Comparing the proportion of each type of subject across the three samples, the share of Competitive, Cooperative, Reciprocating and Individualistic subjects statistically differ across the three samples (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.039, 0.038, 0.071, and 0.000, respectively).

Two categories collect more than 75% of the subjects in each sample: Individualistic and Reciprocating. Considering these two categories, the shares are unbalanced, as there are more Reciprocating subjects among permanent workers and more Individualistic subjects among students. Comparing permanent workers and students, the difference in the share of Individualistic subjects is statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001), while comparing permanent and temporary workers the share of Individualistic subjects is lower among the former category, although the difference is only weakly significant (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.088). When comparing students and temporary workers, the share of Individualistic subjects is higher among students, although the difference is only weakly significant (Fisher’s one sided test, p = 0.080).

Table 5.

Distribution of types in the three samples.

| Type | Temporary | Permanent | Student | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressive | 0% (n = 0) | 1.2% (n = 1) | 2.0% (n = 2) | 1.2% (n = 3) |

| Competitive | 4.2% (n = 3) | 10.7% (n = 9) | 2.0% (n = 2) | 5.6% (n = 14) |

| Cooperative | 2.8% (n = 2) | 5.9% (n = 5) | 0% (n = 0) | 2.8% (n = 7) |

| Individualistic | 41.7% (n = 30) | 22.6% (n = 19) | 55.2% (n = 53) | 40.5% (n = 102) |

| Reciprocating | 44.4% (n = 32) | 54.8% (n = 46) | 37.5% (n = 36) | 45.2% (n = 114) |

| Others | 6.9% (n = 5) | 4.8% (n = 4) | 3.1% (n = 3) | 4.8% (n = 12) |

| Total | 100% (n = 72) | 100% (n = 84) | 100% (n = 96) | 100% (n = 252) |

Focusing on the students’ pool, our results are compatible with those reported in [17], who finds that Individualistic people are the majority (59.9% of her sample) and Reciprocating (which in her taxonomy are called “cooperative”) is the second largest category (37.3%).

We can also check whether the information on distributional and motivational characteristics is consistent among the different classification tasks employed in the experiment. Overall, there is a good degree of consistency although correlations are not perfect. For example, being classified as Beneficent in the Dictator Game is positively correlated to being classified as Reciprocating (Spearman ρ = 0.268), 17 and negatively related to being classified as Individualistic (ρ = −0.282) or as a Free rider (ρ = −0.318) in the Decomposed Game. Being classified as a Beneficent in the Dictator Game is also negatively correlated to being a Free Rider (ρ = −0.138) in the Strategy Method. Considering each group separately, we observe additional differences. In the permanent workers sample, being classified as Reciprocating in the Decomposed Game is negatively related to being classified as Free rider (ρ = −0.239) in the Strategy Method. Interestingly, being classified as an Individualistic in the Decomposed Game is also positively related to being classified as Free rider (ρ = 0.265) in the Strategy Method. In the temporary workers sample, instead, correlations between the different classifications are not significant at the 5% level.

We also ran a multinomial logit regression where the dependent variable is the Decomposed Game Technique classification and where we control for the socio-demographic characteristics of the subjects. 18 For certain categories the sample size is very small, and, therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Table 6 reports the marginal effects, for each category of subjects, of this regression. The results confirm that workers are more likely to be cooperative compared to students.

Table 6.

Multinomial logit (Decomposed).

| Aggressive | Competitive | Cooperative | Individualistic | Reciprocating | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | |

| Student | 0.185 * | 0.11 | 0.090 | −0.034 | 0.06 | 0.582 | −0.369 *** | 0.13 | 0.006 | 0.117 | 0.10 | 0.243 | 0.092 | 0.12 | 0.437 |

| Permanent | 0.195 * | 0.12 | 0.092 | 0.054 | 0.05 | 0.231 | 0.009 | 0.02 | 0.590 | −0.246 ** | 0.11 | 0.021 | 0.035 | 0.10 | 0.730 |

| Male | −0.182 * | 0.11 | 0.089 | −0.045 | 0.04 | 0.259 | 0.035 * | 0.02 | 0.060 | 0.096 | 0.08 | 0.231 | 0.107 | 0.08 | 0.160 |

| Married | −0.184 * | 0.11 | 0.093 | 0.018 | 0.04 | 0.610 | −0.023 | 0.02 | 0.276 | 0.074 | 0.10 | 0.466 | 0.103 | 0.10 | 0.292 |

| NoReligion | −0.179 * | 0.11 | 0.089 | −0.004 | 0.05 | 0.948 | −0.375 *** | 0.13 | 0.004 | 0.185 * | 0.10 | 0.055 | 0.345 *** | 0.11 | 0.002 |

| Degree | 0.014 | 0.01 | 0.305 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.793 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.865 | 0.073 | 0.07 | 0.268 | −0.062 | 0.07 | 0.395 |

| Age | −0.001 | 0.00 | 0.297 | −0.002 | 0.00 | 0.337 | 0.002 ** | 0.00 | 0.044 | −0.001 | 0.00 | 0.777 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.924 |

| Obs | 252 | ||||||||||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.101 | ||||||||||||||

| Prob > F | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

Note: Multinomial logit regression with robust standard errors. The table reports the average marginal effects of the independent variables for each category of the dependent variable. Obs = observations. Prob > F = p-value of F-test. dy/dx = marginal effects. * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

4.4. Linear Public Good Game

The classification tasks reveal that the shares of Unconditional cooperators, Conditional cooperators and Free riders differ among the three samples. In a repeated strategic game this allows making some predictions on the behavior of the subjects, since in the presence of conditional cooperators, feedback on the others participants choices and own earnings should induce adaptation to the behavior of other players and, possibly, learning. In particular, since there is a higher share of Unconditional cooperators among the permanent and temporary workers, as well as a lower share of Free riders, we would expect higher initial levels of contributions in the samples of workers than in the sample of students. Furthermore, we would expect Conditional cooperators to provide high levels of contribution in the subsequent rounds. In contrast, since in the student sample there is a higher share of Free riders, we would expect lower initial contributions, which in turn should induce Conditional cooperators to lower their contributions over time.

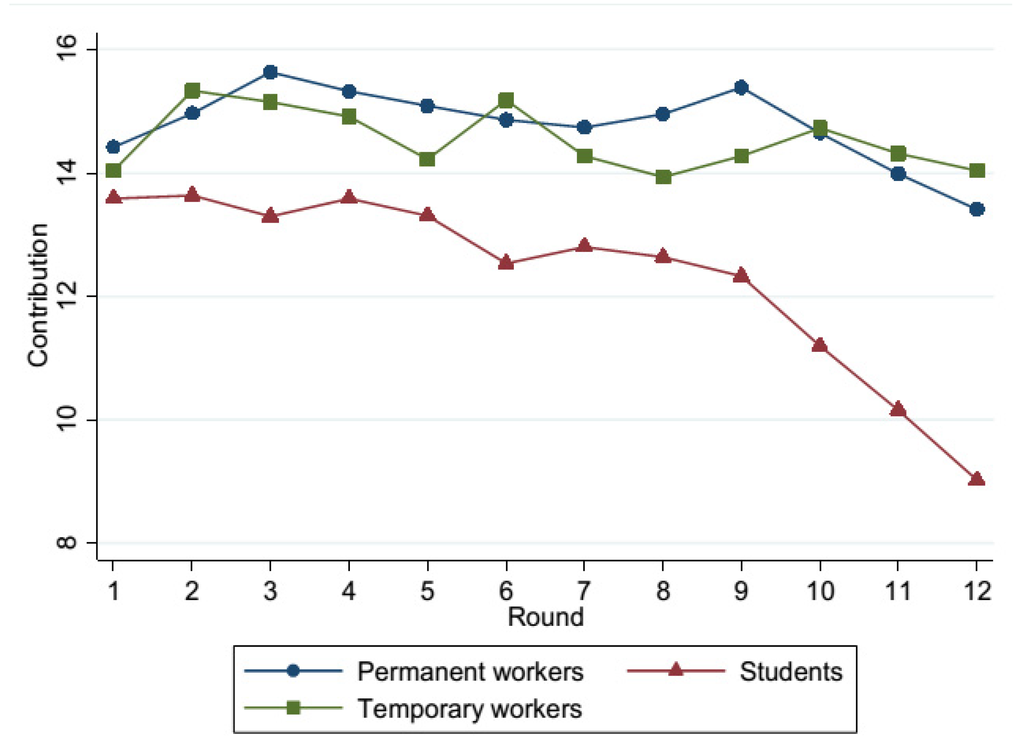

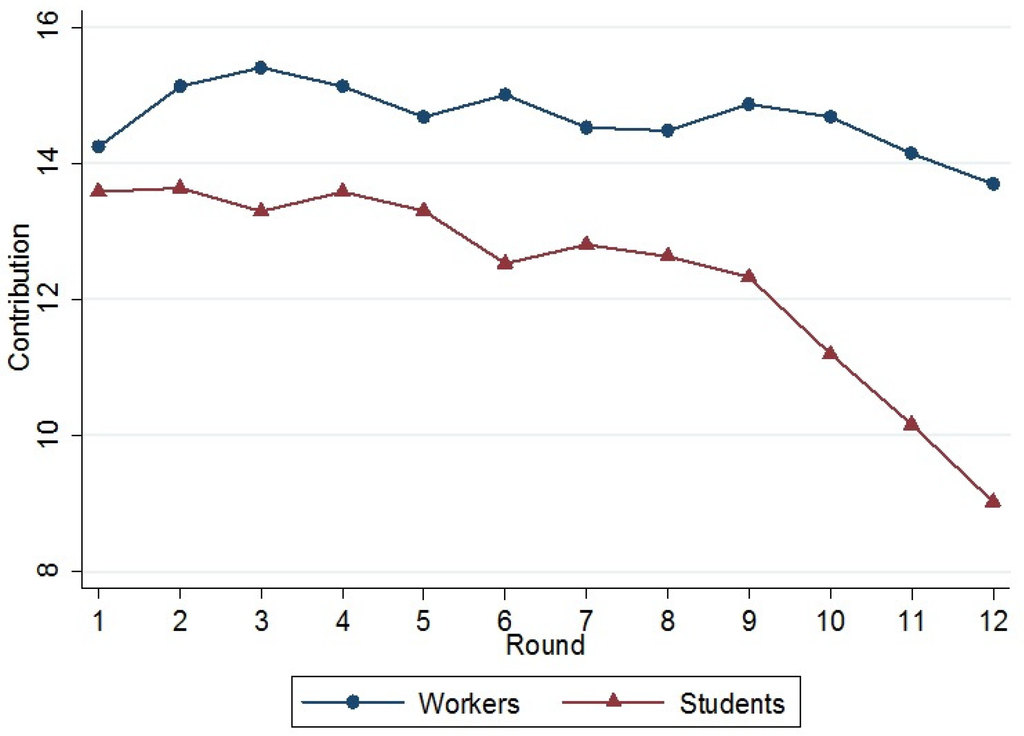

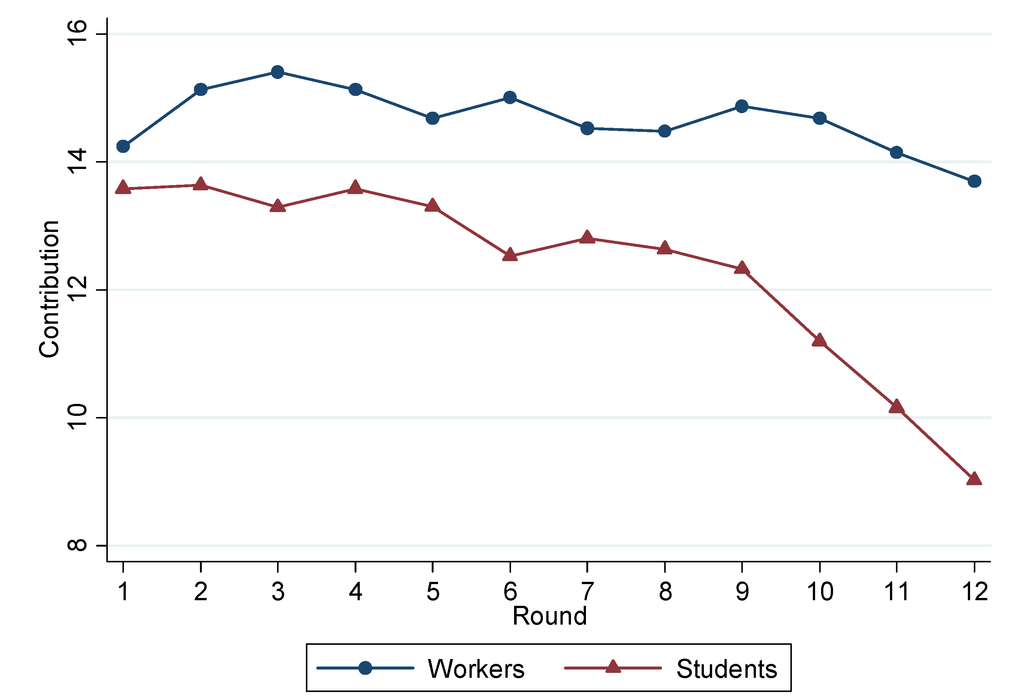

Figure 2 shows the average contribution in the first 12 rounds of the Linear Public Good Game for each subject pool (students, permanent workers, and temporary workers). In Figure 3 we pool workers to highlight the differences between workers and students. Initial contributions do not differ significantly, although we can observe some differences as the game unravels. In the students’ sample, average contributions per round and total average contributions are below those by permanent and temporary workers. Comparing the contributions across the three samples for each round, 19 we reject the hypothesis that the three samples come from the same population only for the last two rounds (Kruskal Wallis test, p = 0.084 and 0.026, respectively). Students contributed significantly less in the last rounds of the Public Good Game compared to permanent (round 10, 11, 12; Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.090, 0.053, and 0.024, respectively) and temporary workers (round 11, 12; p = 0.069, and 0.020, respectively), but we do not detect any significant difference in the average contribution of permanent and temporary workers (p > 0.1). The students’ contributions significantly decrease over time (Spearman ρ = −0.192, p < 0.001). This is a recurrent finding in the literature (see, e.g., [15,16,35]). Interestingly, there is no significant downward trend for temporary and permanent workers (Spearman ρ = −0.016 and −0.060, p = 0.820 and 0.343), with an average contribution that remains quite constant throughout the 12 rounds of the Public Good Game. Hence, we can state the following:

Result 3: Students contribute less than workers and their contributions decrease over time. Temporary and permanent workers contribute on average more than 70% of their endowment and their contributions remain stable over time.

To study how contributions depend on the history of the game, we employ a Poisson-logit maximum-likelihood hurdle model to separate the decision of contributing in two steps (see, e.g., [38]). First, with a logit model we study whether the subjects decide to contribute or not, then with a zero-truncated Poisson model we study the decision about the amount of the contribution, conditional on contributing a positive amount.

Figure 2.

Evolution of average contributions over time (students, permanent, and temporary workers).

Figure 3.

Evolution of average contributions over time (students vs. workers).

Table 7 displays the results of this estimation. In a first model (Hurdle model 1), the independent variables are the sample dummies (the baseline category is “temporary”), a time variable, the positive and negative deviations of i’s contribution from the average group contribution in period t−1, the individual i’s contributions made in t−1 and t−2, and, as in previous regressions, the socio-demographic characteristics of the subjects. In a second model (Hurdle model 2), we also include the classification dummies obtained from the classification tasks. In particular, we consider being Individualistic, Competitive or Reciprocating in the Decomposed Game, Beneficent in the Dictator Game, and being Conditional, Unconditional or a Free rider in the Strategy Method.

Table 7.

Poisson-logit maximum-likelihood hurdle model.

| Hurdle Model 1 | ||||||

| Decision to Contribute | Decision of How Much to Contribute | |||||

| dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | |

| Permanent | −0.032 | 0.022 | 0.134 | −0.459 * | 0.266 | 0.085 |

| Student | −0.043 ** | 0.018 | 0.016 | −0.085 | 0.264 | 0.749 |

| Contribution t−1 | 0.007 *** | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.738 *** | 0.045 | 0.000 |

| Contribution t−2 | 0.003 *** | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.247 *** | 0.027 | 0.000 |

| Positive deviation t−1 | −0.015 *** | 0.002 | 0.000 | −0.305 *** | 0.046 | 0.000 |

| Negative deviation t−1 | −0.010 *** | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.521 *** | 0.113 | 0.000 |

| Period | −0.009 *** | 0.002 | 0.000 | −0.030 | 0.024 | 0.211 |

| Male | −0.015 | 0.013 | 0.278 | 0.131 | 0.209 | 0.531 |

| Married | 0.044 * | 0.026 | 0.092 | −0.030 | 0.241 | 0.899 |

| NoReligion | −0.028 * | 0.016 | 0.075 | -0.086 | 0.256 | 0.738 |

| Degree | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.127 | −0.640 *** | 0.240 | 0.008 |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.235 | 0.029 ** | 0.013 | 0.024 |

| Obs | 2520 | 2292 | ||||

| Hurdle Model 2 | ||||||

| Decision to Contribute | Decision of How Much to Contribute | |||||

| dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | dy/dx | Std. Err. | p > z | |

| Permanent | −0.033 * | 0.019 | 0.093 | −0.369 | 0.286 | 0.197 |

| Student | −0.034 * | 0.017 | 0.052 | −0.086 | 0.281 | 0.758 |

| Contribution t−1 | 0.007 *** | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.732 *** | 0.045 | 0.000 |

| Contribution t−2 | 0.002 ** | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.245 *** | 0.027 | 0.000 |

| Positive deviation t−1 | −0.015 *** | 0.002 | 0.000 | −0.306 *** | 0.046 | 0.000 |

| Negative deviation t−1 | −0.009 *** | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.513 *** | 0.113 | 0.000 |

| Period | −0.009 *** | 0.002 | 0.000 | −0.031 | 0.024 | 0.202 |

| Male | −0.017 | 0.012 | 0.171 | 0.107 | 0.214 | 0.618 |

| Married | 0.033 | 0.024 | 0.167 | −0.051 | 0.244 | 0.835 |

| NoReligion | −0.016 | 0.014 | 0.274 | −0.121 | 0.258 | 0.639 |

| Degree | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.535 | −0.592 ** | 0.242 | 0.015 |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.453 | 0.028 ** | 0.014 | 0.048 |

| Beneficent | 0.026 * | 0.013 | 0.054 | 0.023 | 0.256 | 0.929 |

| Reciprocating | −0.110 ** | 0.051 | 0.032 | 0.699 | 0.472 | 0.138 |

| Individualistic | −0.115 ** | 0.051 | 0.026 | 0.578 | 0.485 | 0.233 |

| Competitive | −0.067 | 0.060 | 0.259 | −0.165 | 0.686 | 0.810 |

| Conditional | −0.005 | 0.017 | 0.774 | 0.062 | 0.259 | 0.812 |

| Free rider | −0.091 *** | 0.025 | 0.000 | −0.866 | 1.147 | 0.450 |

| Unconditional | −0.023 | 0.022 | 0.310 | 0.394 | 0.491 | 0.422 |

| Obs | 2520 | 2292 | ||||

Notes: The decision to contribute is estimated with a logit model with clustered standard errors at individual level. The decision of how much to contribute is estimated with a zero-truncated Poisson model with clustered standard errors at individual level. In the table, we report the average marginal effects of the independent variables. Obs = observations. Prob > F = p-value of F-test. dy/dx = marginal effects. * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

The results of the estimation appear to be consistent with our expectations based on the shares of Free riders, Unconditional and Conditional co-operators detected in the classification task (in particular, in the Strategy Method). From the first model, we observe that students are less likely to contribute a positive amount compared to temporary and permanent workers. This result may be explained by the larger proportion of Free Riders and the smaller proportion of Unconditional contributors among students. Indeed, once we include the classification dummies in the regressions (Hurdle model 2), the point estimate for the variable students decreases and becomes only weakly significant, whereas the variable Free Rider is negative and strongly significant, suggesting that subjects who are classified as Free Riders in the Strategy Method are less likely to contribute to the public good. 20 In both the first and second models, we also find that the probability of not contributing to the public good significantly increases across periods, and it increases if the subject’s contribution in the previous period had not matched the average contribution of her group. There is also evidence that subjects are more likely to contribute a positive amount the higher their contribution in the previous rounds (this effect is small, but highly significant). 21 When considering the decision of how much to contribute (conditional on contributing a positive amount), in both models we observe that current contributions are positively correlated to past contributions, and they increase if the subject’s contribution in the previous period was smaller than the average contribution of the group. Furthermore, subjects who contributed above the average in the previous period adjust their decision and reduce their contribution in the current round, and older and more educated subjects contribute more than younger subjects. Finally, in the first model we also have some weakly significant evidence that, conditional on contributing a positive amount, permanent workers contribute less than temporary workers.

5. Discussion

In this paper, we investigate two main research questions. First, we study whether we can detect differences in behavior and social preferences between undergraduate students and workers. Second, focusing on the sample of workers, we investigate whether temporary contract and permanent contract workers behave similarly, or whether the type of contractual arrangement is correlated with observable differences.

With respect to the first research question, we find that students tend to be more self-oriented, and less willing to cooperate in a public good game. This result is consistent with similar findings in the literature (for a recent review and a methodological discussion see, e.g., [39]). For instance, using a public good game, Gächter and Herrmann [40] show that students are less prosocial than rural and urban citizens, and Cardenas [41] shows that they extract more resources than rural villagers in a common pool resources experiment. Similar findings are observed when comparing students with workers, such as nurses [5], bicycle messengers [8], shrimp fishermen [13], and white-collar workers [42]. Previous studies suggest that students seem to be at the lower bound of other-regarding preferences. In this paper, we confirm this finding, thereby contributing a little further to the robustness of the results presented in the literature using undergraduate subjects.

Also, we find that there are marked differences between students and workers in the patterns of contributions in the repeated public good game, which suggests that different preferences translate in substantial differences in behavior in strategic settings. The reasons for the observed differences between students and non-students can be attributed to a variety of reasons. For example, in a field study, List [2] suggests that age might play a crucial role, since he finds that younger and middle-aged subjects tend to contribute to a public good at rates consistent with extant laboratory data, whereas older subjects contribute larger amounts of their endowment. Similarly, cooperation rates in prisoner’s dilemma games are greater among older than among younger subjects. The existing experiments contrasting students and workers also suggest that the exposition to a working environment might endogenously affect the propensity to cooperate. Which factors lead workers to be more cooperative or to become more opportunistic may in principle depend on several reasons, including the work climate, the type of job, the type of employee or the type of contractual arrangement.

Before running the experiment to address the second research question, we expected to find a significantly lower propensity to cooperate in the group of temporary workers with respect to the group of permanent (co-op) workers, as the former are less likely to know each other and they have received no specific training on the values of cooperation and mutualism. In addition, in terms of social distance co-op permanent workers are closer to each other than temporary workers [43]. The experimental results show, instead, that temporary and permanent workers contribute substantially and in a very similar way to the public good over the 12 rounds of the game. This result holds even if temporary workers tend to be slightly more individualistic than permanent workers.

This finding is suggestive and it deserves a deeper discussion, with the caveat that our study has some limitations. In particular, due to the difficulties in recruiting workers as experimental subjects and to the data availability, we cannot provide clean comparisons between the two categories of workers. Taking into account these limitations, we can still make some conjectures on the reasons why the two samples do not differ as much as expected. A possible explanation for the results in the Public Good Game relies on the large proportion of Unconditional contributors in both the temporary and permanent workers samples (and, analogously, on the low proportion of Free Riders). This may have helped a sustained high level of cooperation for Conditional contributors, thereby maintaining high average contribution rates. In contrast, the higher share of Free Riders among students might have induced Conditional cooperators to lower their contributions over time in response to the low contributions of Free Riders. This interpretation is consistent with the results shown in Table 7, which allows joining and comparing the information on the distributional preferences of the subjects obtained in the Classification stage of the experiment with the Strategic behavior observed in the repeated Public Good Game.

A second possible explanation is that workers, irrespective of whether they are employed under a temporary or permanent contract, are less selfish than students. This explanation would suggest that socialization processes due to working experiences and age could be major factors. If workers have learnt that cooperating provides long-run benefits, they may have brought this experience into the lab and use it when contributing in the Public Good Game. Students, instead, are more used to individual rather than team work and have less experience with repeated interactions and the related reputational concerns. Moreover, students participating in lab experiments may be a selected population with a stronger focus on earning money [31]. Unfortunately, our design does not allow disentangling this kind of selection issues. 22

Subjects only knew that the pools were homogeneous. This might have induced an in-group bias. For example, temporary workers may have chosen their contributions based on mutual insurance considerations. Accordingly, they might have contributed to the public good knowing that the other group members were also temporary workers, and this may have stimulated high contributions. However, this effect should be stronger among the permanent workers, as they work for the same cooperative and meet each other daily, but we detect no significant difference with respect to temporary workers. This result shows that temporary and permanent arrangements do not affect the propensity to cooperate to a public good when workers are part of a homogeneous group. As far as we know, this is the first experimental evidence showing this finding. A different, but related, question which we leave for future investigation is whether heterogeneous groups composed by both temporary and permanent workers display the same levels and trends of contributions.

Our a priori expectation of a higher contribution rate among permanent workers was based on the fact that they know each other, that they work in the same place, and that the common employer is a co-op which actively emphasizes the values of mutualism and cooperation. It is however possible that some other factors may have driven the behavior of permanent workers toward an unexpected direction. Knowing each other is not a guarantee per se of a high social capital and willingness to cooperate, as human relationships can improve, but as well deteriorate over time. Analogously, being constantly exposed to the values of mutualism does not ensure these values are internalized by workers, since these values may possibly be rejected. If this were the case, we should observe low contribution rates. The result that the observed contribution rates of permanent workers are significantly higher than those of students and that they remain quite high over time (about 60% of the initial endowment), however, does not support this hypothesis.

The high degree of cooperative and other-regarding behavior observed among temporary workers may be due to positive selection and signaling effects. As observed by Engellandt and Riphahn [24], temporarily employed workers may have below average risk-aversion and accept temporary jobs to signal their ability and qualify for permanent positions. In a similar fashion, social and labor psychologists refer to impression management, as the systematic attempt by temporary workers to behave in a way that pleases the employee [44]. Such an attitude might have been brought by the temporary workers into the lab, and push them to cooperate. Although this possibility cannot be excluded a priori, we made very clear that the participation to our experiment was a one-shot experience, and that in no way we would have communicated the results of their individual choices to the recruitment agency.

It is possible that the common social environment in which both temporary and permanent workers live has played a major role for working people. The social environment can overwhelm the role of investments in the values of cooperation by the co-operative, or the possible differences induced by permanent and temporary work arrangements. This can be the case, as the places where the experiments were conducted (located within the Emilia-Romagna region, Italy) are characterized by high levels of social capital and generalized trust [42]. This may have shaped in a similar way the behavior of both temporary and permanent workers, as well as that of the students raised in Emilia-Romagna. However, this conjecture is not consistent with the finding that students display significantly lower contribution rates even when controlling for age. Hence, if the reason for the scant difference in the contribution rates of temporary and permanent workers relies on the existence of a high social capital at the regional level, one should also explain why this seems to affect more workers than students. This requires additional data aimed at understanding whether our results also hold in regions where social capital is low. 23

6. Conclusions

Assessing the robustness of results obtained in a controlled environment using different subject pools is key for the evaluation of the external validity of experimental studies. We address this issue by running an artefactual field experiment using three different subject pools: undergraduate students, temporary contract workers, and permanent contract workers.

The results obtained when contrasting students with workers are consistent with the findings available in the literature: students tend to be less prosocial than workers. We find, instead, only minor differences in the distributional preferences of the two groups of workers, and a very similar behavior in a Public Good Game. Workers, irrespective of the type of their contractual arrangement, begin with high levels of contribution to the public good, and contributions remain high over time. In the sample of students, instead, contributions begin at high levels, but then decline considerably over time.

While the latter result is in line with the previous experimental evidence on the Public Good game, the high and steady level of contributions by workers is a less common finding. A possible explanation for this result is that the different contractual arrangements, and the consequent economic and psychological effects, play a minor role with respect to other factors. For example, socialization and learning on the job may have induced both temporary and permanent workers to behave similarly and avoid free-riding opportunities. Also, in-group and mutual insurance considerations may have driven workers to contribute to the public good. In either case, our paper documents that, in our sample of subjects, students cooperate less than workers, and that temporary and permanent workers cooperate at similar rates. This is a novel and somehow unexpected result which deserves further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Formula Servizi and Obiettivo Lavoro for their precious assistance in recruiting the experimental subjects. We thank Maria Bigoni, Stefania Bortolotti, Marco Casari, Caterina Giannetti, Vera Negri Zamagni, the participants at the 2011 BEELab conference in Florence (Italy), two anonymous referees, and the guest editor Ananish Chaudhuri for comments and suggestions. Financial support from the PRIN 2007/B8SC7A_002, the University of Bologna Strategic Project “Ethical Values and Competitiveness of Italian Cooperative Companies”, CFICEI (Centro di Formazione e Iniziativa sulla Cooperazione e l’Etica d’Impresa) and AICCON is gratefully acknowledged. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author Contributions

All the authors contributed equally to this article.

Appendix

A. Participants, Sessions, and Additional Analysis

A.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

Table A1.

Subjects’ socio-demographic characteristics.

| Characteristics | Permanent | Student | Temporary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | (n = 84) | (n = 96) | (n = 72) |

| Female | 58 (69.05%) | 52 (54.17%) | 43 (59.72%) |

| Male | 26 (30.95%) | 44 (45.83%) | 29 (40.28%) |

| Age | (n = 84) | (n = 96) | (n = 72) |

| Mean | 41.64 | 23.94 | 31.67 |

| St. dev. | 9.19 | 4.57 | 9.39 |

| Marital Status | (n = 84) | (n = 96) | (n = 72) |

| Married | 44 (52.38%) | 1 (1.04%) | 13 (18.06%) |

| Unmarried | 40 (47.62%) | 95 (98.96%) | 59 (81.94%) |

| Nationality | (n = 84) | (n = 96) | (n = 72) |

| non-Italian a | 7 (8.33%) | 5 (5.21%) | 8 (11.11%) |

| Italian | 77 (91.67%) | 91 (94.79%) | 64 (88.89%) |

| Religion | (n = 84) | (n = 96) | (n = 72) |

| Agnostic/Atheist | 9 (10.71%) | 28 (29.17%) | 15 (20.83%) |

| Christian | 71 (84.52%) | 64 (66.67%) | 42 (58.33%) |

| Other b | 4 (4.76%) | 4 (4.17%) | 15 (20.83%) |

| Education | (n = 84) | (n = 96) | (n = 72) |

| Lower Secondary School or less | 56 (66.67%) | 95 (98.96%) | 52 (72.22%) |

| Upper Secondary School or more | 27 (32.14%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (19.44%) |

| Other | 1 (1.19%) | 1 (1.04%) | 6 (8.33%) |

| Years of work | (n = 36) c | (n = 72) | |

| Mean | 19.42 | 10.22 | |

| St. dev. | 10.59 | 9.01 | |

| Years of work in cooperative | (n = 36) c | ||

| Mean | 10.01 | ||

| St. dev. | 6.88 | ||

| Years of work as temporary | (n = 72) | ||

| <1 | 41 (56.94%) | ||

| >1 | 31 (43.06%) | ||

| Working days as temporary worker (last 12 months) | (n = 72) | ||

| Mean | 46.04 | ||

| St. dev. | 87.55 | ||

| Working days as temporary worker (total) | (n = 72) | ||

| Mean | 92.22 | ||

| St. dev. | 189.96 | ||

| Months worked in cooperative | (n = 71) d | ||

| Mean | 14.2 | ||

| St. dev. | 83.97 | ||

| Student status | (n = 72) | ||

| Only worker | 58 (80.56%) | ||

| Lower Secondary School or less | 1 (1.39%) | ||

| Upper Secondary School or more | 11 (15.28%) | ||

| Other | 2 (2.78%) |

Notes: a Seven were Albanian, 1 Brazilian, 2 Moldavian, 1 Polish, 5 Romanian, 2 Senegalese, 1 Serb, and 1 Hungarian. b Two were Buddhist, 1 Indu, 6 Muslim, and 14 did not specify. c This information was collected only for a subset of permanent workers. d One subject did not specify how many months she worked in a cooperative.

If we compare the proportion of males and females across the three samples, we do not detect any statistically significant difference (Chi-squared test, p = 0.122). In pairwise comparisons, the only statistically significant different occurs between permanent workers and students. In particular, the proportion of females is significantly lager in the permanent workers sample compared to the students sample (p = 0.041). There is no statistically significant difference in the proportion of females between temporary and permanent workers, and temporary workers and students (p = 0.224 and 0.472 respectively). The three samples statistically significantly differ with respect to age (Kruskal Wallis test, p < 0.001). In particular, permanent workers are significantly older than students and temporary workers (Mann-Whitney p < 0.001 for both, pairwise comparison), and temporary workers are significantly older than students (p < 0.001). If we look at the marital status of the subjects, the three samples statistically significantly differ both in aggregate (Chi-squared test, p < 0.001) and in pairwise comparisons (p < 0.001). In particular, the proportion of permanent workers who are married is significantly larger than students and temporary workers. Similarly, the proportion of married subjects in the temporary workers sample is significantly larger than in the students’ sample. Almost the totality of the participants is Italian (92%). Only few subjects are not from Italy. Those who are not Italian are Albanian, Brazilian, Moldavian, Polish, Romanian, Senegalese, Serb, or Hungarian. If we compare the proportion of non-Italian across the three samples, we do not detect any statistically significant difference (Chi-squared test, p = 0.370). A similar result is obtained in pairwise comparisons (p > 0.1). If we look at the religious affiliation, subjects statistically significantly differ in their religious beliefs across samples (Chi-squared test, p< 0.001). This evidence is also supported in pairwise comparisons (Chi-squared test, p < 0.01). More specifically, the fraction of Christians is larger among permanent workers than temporary workers and students. Students are generally more agnostic/atheist. The proportion of participants who are neither Christian nor agnostic/atheist is larger among temporary workers compared to students and permanent workers. In general, permanent workers are more religious than students (p = 0.002) and temporary workers (p = 0.081). In contrast, temporary workers are not statistically significantly more religious than students (p = 0.221). If we compare the level of education, the three samples statistically significantly differ (Chi-squared test, p < 0.001). In particular, a higher proportion of students possess a higher degree compared to permanent and temporary workers (Chi-squared test, p < 0.001). No statistically significant difference occurs between temporary and permanent workers on the level of education (Chi-squared test, p = 0.124). If we compare the years of work of permanent and temporary workers, permanent workers have more years than temporary workers (Mann-Whitney p < 0.001).

A.2. Details of the Sessions

Table A2.

Details of the sessions.

| Session | Sample Pool | Number of Participants | Date (Day/Month/Year) | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Students | 12 | 29/07/2009 | Forli |

| 2 | Students | 12 | 29/07/2009 | Forli |

| 3 | Permanent workers | 12 | 03/09/2009 | Forli |

| 4 | Permanent workers | 12 | 03/09/2009 | Forli |

| 5 | Permanent workers | 12 | 04/09/2009 | Forli |

| 6 | Students | 24 | 14/04/2010 | Forli |

| 7 | Permanent workers | 12 | 14/04/2010 | Forli |

| 8 | Permanent workers | 12 | 16/04/2010 | Forli |

| 9 | Students | 24 | 16/04/2010 | Forli |

| 10 | Permanent workers | 12 | 16/04/2010 | Forli |

| 11 | Permanent workers | 12 | 21/04/2010 | Forli |

| 12 | Students | 12 | 24/02/2011 | Forli |

| 13 | Students | 12 | 24/02/2011 | Forli |

| 14 | Temporary workers | 12 | 24/02/2011 | Bologna |

| 15 | Temporary workers | 12 | 25/02/2011 | Forli |

| 16 | Temporary workers | 12 | 25/02/2011 | Forli |

| 17 | Temporary workers | 12 | 04/03/2011 | Forli |

| 18 | Temporary workers | 12 | 25/03/2011 | Bologna |

| 19 | Temporary workers | 12 | 21/06/2011 | Bologna |

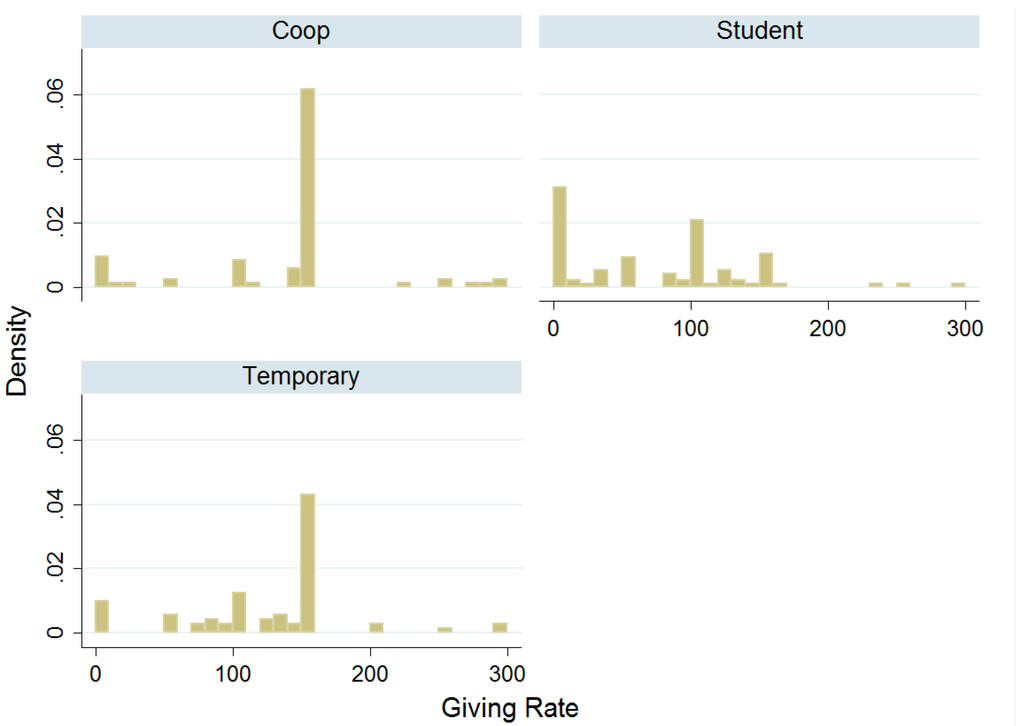

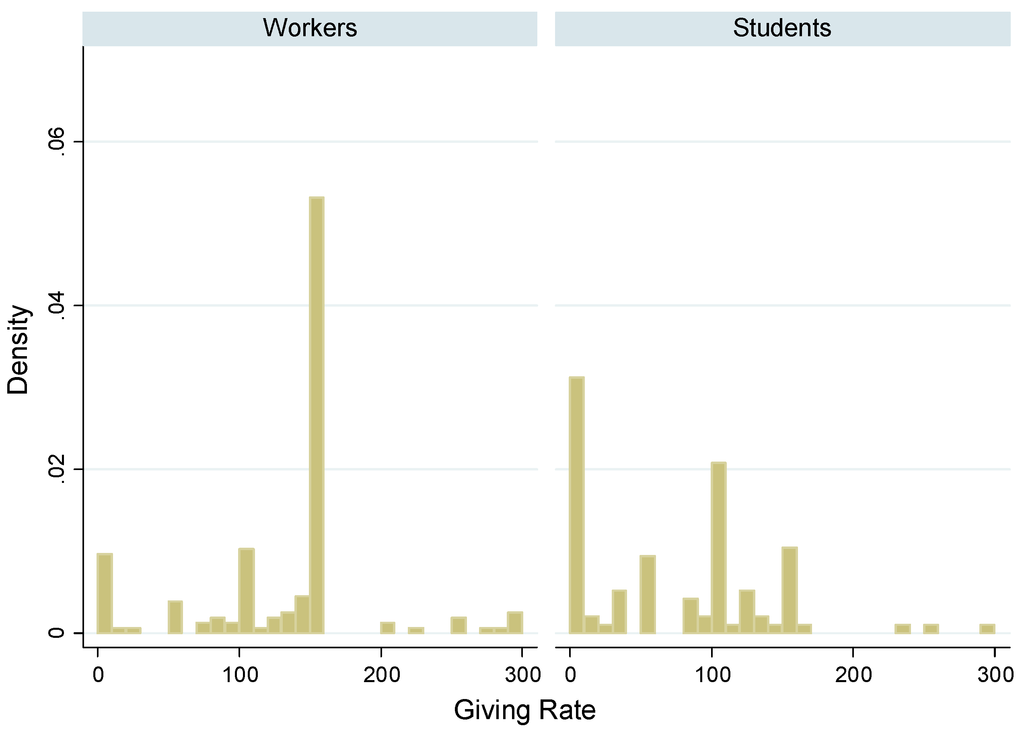

A.3. Distribution of Offers in the Dictator Game

Figure A1 shows the distribution of the offers per sample. Comparing the distributions of the offers between permanent workers and students, we reject the null hypothesis that they are the same (Epps-Singleton test, p < 0.001). A similar result holds when comparing temporary workers and students (Epp-Singleton test, p < 0.001). When we compare the sample distributions of the offers between temporary and permanent workers, we only weakly reject the hypothesis that they have been drawn from the same population (Epps-Singleton p = 0.077).

Figure A1.

Dictator Game: distribution of offers.

A.4. Unconditional Contributions and Beliefs in the Strategy Method

If we look at the unconditional contributions in the Strategy Method (Table A3), they weakly statistically differ across samples (Kruskal Wallis test, p = 0.061). In particular, if we conduct pairwise comparisons, students contributed on average less than permanent and temporary workers. However, the difference is statistically significant only when comparing students with permanent workers (Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.021). The beliefs do not significantly differ across samples, or in pairwise comparisons. Interestingly, the average contributions of both permanent and temporary workers are statistically higher than their beliefs about the contribution of the others (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p < 0.001 and 0.001, respectively), whereas contributions and beliefs of students do not statistically differ (Wilcoxon signed-rank test p = 0.609). This result support the evidence that permanent and temporary workers are more likely to be unconditional co-operators compared to students, i.e., they contribute no matter what is the contribution of the others.

Table A3.

Unconditional contributions and beliefs.

| Sample | Contribution | Belief | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Err. | Mean | Std. Err. | |

| Permanent (n = 84) | 118.99 | 57.54 | 102.34 | 54.05 |

| Student (n = 96) | 97.88 | 60.18 | 105.71 | 47.10 |

| Temporary (n = 72) | 112.13 | 53.75 | 101.19 | 46.27 |

| Total (n = 252) | 108.99 | 58.02 | 103.30 | 49.14 |

We also ran a Tobit regression where the dependent variable is the unconditional contribution. Independent variables include dummy variables for the experimental sample (using the temporary workers as baseline category), age, gender (Male = 1 for male subjects), relationship status (Married = 1 for married subjects), religious affiliation (NoReligion = 1 for atheist or agnostic subjects), educational background (Degree = 1 for subjects with a university degree), and beliefs. Table A4 displays the results of the regression. When covariates are controlled for, we observe that students contribute significantly less than temporary workers, whereas the unconditional contributions of permanent workers do no statistically differ from those of temporary workers. In addition, there is strong evidence that the contribution is positively related to the beliefs about the contribution of the others. This result does not surprise since about 70% of the subjects were classified as conditional co-operators.

Table A4.

Tobit regression (unconditional choice).

| β | Std. Err. | p > z | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belief | 0.991 *** | 0.08 | 0.000 |

| Student | −20.937 ** | 8.71 | 0.017 |

| Permanent | 6.864 | 9.05 | 0.449 |

| Male | −4.767 | 7.41 | 0.521 |

| Married | −12.099 | 9.11 | 0.185 |

| NoReligion | −9.649 | 9.24 | 0.298 |

| Degree | 8.562 | 7.95 | 0.282 |

| Age | 0.574 | 0.38 | 0.129 |

| Constant | 2.708 | 15.12 | 0.858 |

| Obs | 252 | ||

| ll | −1113.4 | ||

| Prob > F | 0 |

Note: Tobit regression with robust standard errors. Obs = observations. Prob > F = p-value of F-test. ll = log-likelihood. ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

A.5. Decomposed Prisoner’s Dilemma

Table A5.

Choice of allocations.

| Question | Option A | Option B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self | Other | Self | Other | |

| 1 | 150 | 0 | 145 | 39 |

| 2 | 144 | −39 | 130 | −75 |

| 3 | 130 | −45 | 106 | −106 |

| 4 | 106 | −106 | 75 | −130 |

| 5 | 75 | −130 | 39 | −145 |

| 6 | 39 | −145 | 0 | −150 |

| 7 | 0 | −150 | −39 | −145 |

| 8 | −39 | −145 | −75 | −130 |

| 9 | −75 | −130 | −106 | −106 |

| 10 | −106 | −106 | −130 | −75 |

| 11 | −130 | −75 | −145 | −39 |

| 12 | −145 | −39 | −150 | 0 |

| 13 | −150 | 0 | −145 | 39 |

| 14 | −145 | 39 | −130 | 75 |

| 15 | −130 | 75 | −106 | 106 |

| 16 | −106 | 106 | −75 | 130 |

| 17 | −75 | 130 | −39 | 145 |

| 18 | −39 | 145 | 0 | 50 |

| 19 | 0 | 150 | 39 | 145 |

| 20 | 39 | 145 | 75 | 130 |

| 21 | 75 | 130 | 106 | 106 |

| 22 | 106 | 106 | 130 | 75 |

| 23 | 130 | 75 | 145 | 39 |

| 24 | 145 | 39 | 150 | 0 |

Figure A2.

The “value orientation circle”.

A.6. Instructions 24

Introduction

Welcome to the Laboratory of Experimental Economics of the University of Bologna.

You will participate in a study on individual behavior of about one hour and a half. If you read these instructions carefully, you can, depending on your decisions, earn some money. For your convenience, instructions are provided both on screen and on paper.

Your earnings will be calculated in florins and will be converted into Euros at the end of today’s session. Every florin equals 1 euro cent. Payment will be made in cash at the end of this session and it will be done in such a way that no other participant will know how much you have earned.

The experiment is divided into various stages. At each stage you will be asked to make some decisions or to answer a few simple questions.

From now on it is forbidden to talk to the other participants, or communicate in any other way. If you want to ask a question, raise your hand.

STAGE ONE

Situation

In this stage each of you is randomly matched with another participant. The identity of the participant with whom you are matched remains anonymous. You will never know with whom you are matched.

For each pair of participants, the computer assigns 300 florins, which are randomly given to only one of the two members of the couple. The other participant gets nothing.

Those who receive the 300 florins can decide whether to keep them all or give part of the florins to the other participant they are matched with. Those who have not received the 300 florins, instead, can only receive florins from their partner.

You cannot currently know whether you are one of those who will receive the 300 florins, because those who will receive 300 florins will be randomly selected at the end of stage seven.

What you should do in stage one

At this stage we ask you to indicate how you would divide 300 florins between you and the other person, in case you are randomly selected to receive the 300 florins. If, at the end of stage seven, you actually receive the 300 florins, then your choice will be implemented. If, instead, your partner will be selected, her/his choice will be implemented, and you will receive the amount of florins indicated by her/him.

Push the button “Continue” and make your choice.

STAGE TWO

Situation

In this stage, each of you is randomly matched with three other participants to form a group of four persons. The identity of the other participants is anonymous and you will not know with whom you are matched.

Each person receives 200 florins and must decide how many florins to put in her/his own personal account and how many to invest in a project. The overall payoff is given by the personal account plus the earnings resulting from the project.

Earnings from the personal account: For each florin you put in your personal account you will earn exactly one florin.

For example, if you put 200 florins in your personal account (and therefore you do not invest in the project), you will earn exactly 200 florins. If you put 60 florins in your personal account, you will earn 60 florins.

Earnings from the project: The earnings resulting from the project depend on your choices and the choices of the other members of the group. For each member of the group, the earnings from the project will be determined as follows:

- 1)

- All florins given by the group members are summed up.

- 2)

- The sum is doubled.

- 3)

- The doubled sum is divided into four equal parts and assigned to each group member.

Now let’s see two examples to better understand how the earnings from the project are calculated:

Example 1: If the sum of all contributions to the project is 300 florins, each group member will receive individually:

(300 florins multiplied by 2 and then divided by 4) = 150 florins from the project.

Example 2: If the four members of the group invest 25 florins each, and then the sum of their investment is 100 florins, each group member will receive:

(100 florins multiplied by 2 and then divided by 4) = 50 florins from the project.

Practice in stage two

Please answer the following questions. The purpose is to practice with the computation of the earnings you will get. The answers you give to these questions will not affect your final earnings. (If you like, you can use the electronic calculator that you can activate by pressing the small button at the bottom of the screen).

- Each member of the group has 200 florins at his disposal. Suppose that none of the four members of the group (including you) contributes to the project.

- How much will your total earnings be (income + personal project)?

- What will the individual earnings of the others members of the group be?

- Each member of the group has 200 florins at his disposal. Suppose you put 200 florins in the project and each of the other members of the group puts 200 florins.

- How much will your total earnings be (income + personal project)?

Start of Stage Two

Now the choice situation we have just described begins. You will be given 200 florins and you will decide how much you want to put in your personal account and how much in the project. The mechanism for calculating earnings is the one just described.

What you should do in stage two

In this stage you will make two kinds of choices: we will call the first “single choice” and the second “choice in the table”. Your earning in this stage depends both on what you have chosen in the “single choice”, and on what you have chosen in the “choice in the table”.

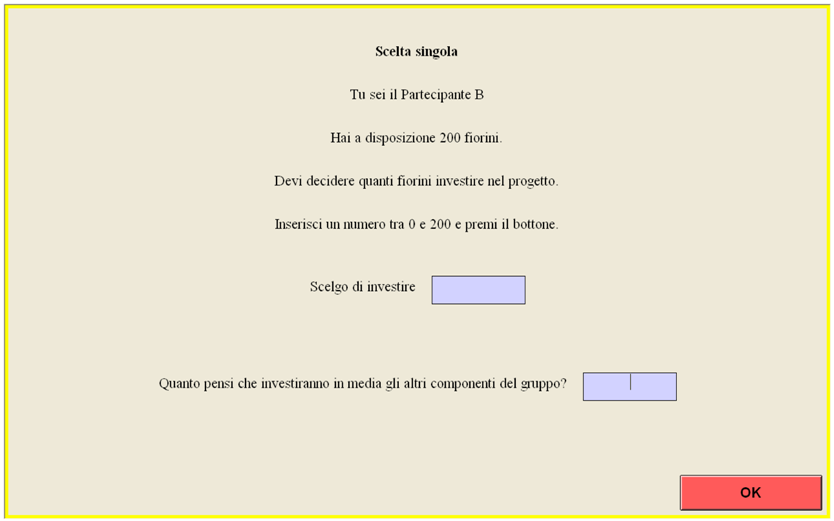

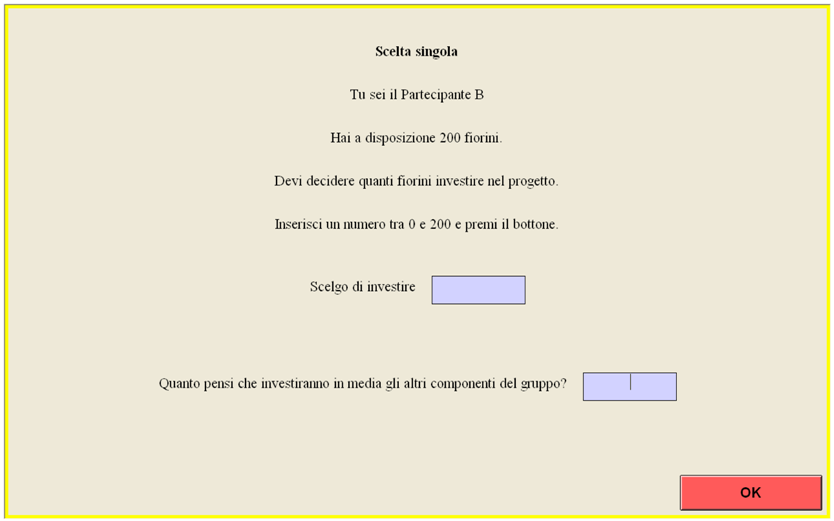

Single Choice

With the single choice you have to decide how many of the 200 florins you want to put in the project.

You also have to indicate how much you think that others are investing in the project. If your guess is at 3 florins or closer from the actual average, you earn 3 extra florins.

On your screen you will see this:

After pressing the “OK” button, you will go to the “choice in the table”.

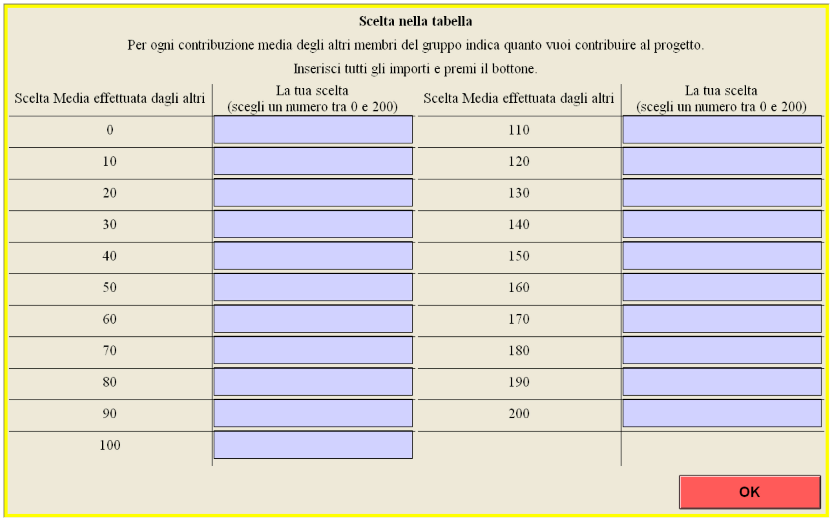

Choice in the table: The screen for the “choice in the table” will look like this:

For example, in the third cell of the first column you are asked to indicate how much you would like to contribute to the project if the average contribution of each of other members of your group is 20 florins. Or, in the third cell of the second column you are asked to indicate how much you would like to contribute if each of the other group members contributes (on average) 130 florins.

Results of stage two

After all participants to the experiment have given their answers, the computer will randomly select a person in each group.

The computer will take the choices made by the other 3 people in the “single choice” and it will compute the average of their contributions. Then it will consider what is the contribution choice indicated by the fourth person in the “choice in the table” in correspondence of the average contribution of the other three members.

By combining this information, the computer:

- Will compute the total contribution of the group by adding the three individual contributions (single choice) and the contribution given by the selected person (choice in the table);

- Will determine the earnings from the project, by doubling the total amount of the contributions to the project;

- Will give a quarter of the doubled sum to each member of the group.

Since you do not know who will be selected by the computer to determine the choice in the table, when you have to fill in the single-choice and the choice in the table, you have to think carefully about both types of choice because both can prove to be decisive in the determination of your earnings.

The computer draw and the result of these computations will be communicated at the end of stage seven. Press the “Continue” button to begin.

STAGE THREE

Situation

At this stage you have to choose between two options, Option A and Option B. The two options are related to sums of money that you and another participant will earn. For example, you may be asked to choose between two options, A and B, where Option A is a gain of 145 florins for you and a loss of 39 florins for another participant, while Option B means a gain of 130 florins for you and a gain of 75 for the other participant. The other participant will have to choose from the same options. An example of the choice between A and B is the following:

There is a total of 24 pairs of choices, and you will be matched with the same participant (selected at random by the computer at the beginning of stage three) for all 24 pairs of choice. The identity of the other participant will remain anonymous, and no one will know who has been matched with.

Your payoff depends on your choices and on those of the other participant, and it is given by the sum of the choices made by you and the other participant.

Going on with the previous example, if you choose Option A (a gain of 145 florins for you, a loss of 39 loss for your partner), and the other chooses Option B (a gain of 130 florins for her/himself and a gain of 75 florins for you), you will earn 145 + 75 = 220 florins, while the other participant will earn −39 + 130 = 91 florins. If, instead, also the other chooses Option A, you will earn 145 + 75 = 220 florins, while the other participant will earn −39 + 130 = 91 florins. If, instead, the other also choses Option A, you will earn 145 − 39 = 106.

What you should do in stage three

In this stage we ask you to make 24 choices between Options A and B. The options will be different each time.

Results

The overall outcome of your choices will be known only at the end of stage seven. In any case, you will be paid privately and you will not know the identity of the other participant, nor she/he will know yours.

Before starting with stage three, we ask you to answer some questions. The purpose is to practice with the computations of the earnings you will get. The answers you give to these questions will not affect your final earnings.

In the situation described below:

- If both choose Option B

- How much do you earn?

- How much does the other participant earn?

- If you choose Option B, while the other participant chooses A

- How much do you earn?

- How much does the other participant earn?

STAGE FOUR

Situation