Abstract

We consider a market setting where a consumer holds either a naive or sophisticated perception of their preference over products. We introduce the concept of a cognitive equilibrium, in which the consumer can transition between the cognitive states of naiveté and sophistication depending on the degree of exploitation in the market. We compare market outcomes under monopoly and competition. While competition unambiguously improves market outcomes when the consumer’s cognitive state is exogenous, it can strictly lower gains from trade when cognitive states are endogenously determined.

1. Introduction

There often exists a wedge between the preferences of an individual and their perception of these preferences. The economics literature has successfully incorporated such naive individuals into their models in order to explain empirical observations in a broad range of contexts1. Alternatively, individuals may have a sophisticated understanding of their true preferences. Whether an individual is naive or sophisticated is usually modeled as a fixed characteristic or ‘type’ of the individual in question2. There is psychological evidence, however, that suggests that movement between these cognitive states is more fluid3. In line with this idea, we provide a novel equilibrium concept called cognitive equilibrium in which a consumer can transition between naiveté and sophistication depending on the benefits and costs associated with doing so. We show that allowing for endogenous determination of the consumer’s cognitive state leads to novel findings in terms of how the degree of competition affects market outcomes relative to the exogenous case.

Consider the following motivating example. A consumer seeks to enter into a new phone plan. Each plan has a number of features, such as the number of minutes for making calls, number of texts that can be sent, the amount of data included, etc. The value of each plan to the consumer will depend on the extent to which she will use each of these features (e.g., how often she will make phone calls, send text messages, and watch videos). At the time of selecting the plan, she expects to utilize each feature more than she actually will (i.e., is naive). The phone provider wants to take advantage of this misperception by offering more and more seemingly attractive features, even if they are not of use to the consumer. At the same time, however, the provider recognizes that, if they try to exploit the consumer too much, then they may become aware of their misperception and avoid entering the plan (i.e., become sophisticated). As such, the phone provider needs to take into account the consumer’s motivation to correct any preference misperception when designing plans. We develop an equilibrium theory that captures such potential for the consumer to endogenously transition from naiveté to sophistication.

The model is as follows. A set of firms offer menus of products to a consumer. Products provide the consumer with a level of a provision of some good at a price. The consumer is either naive or sophisticated. If naive, they overvalue products relative to their sophisticated counterpart by perceiving that the good is more valuable to them than it actually is. Instead, if sophisticated, they correctly perceive their preference over products. The consumer starts out naive but can endogenously transition from naiveté to sophistication by investing in costly cognition. Specifically, the consumer makes this transition if the difference between the true utility received if they are sophisticated (and able to make an optimal decision) and that which they receives if naive (and make a sub-optimal decision) exceeds some cognitive cost. We introduce a solution concept called cognitive equilibrium in which firms take into account the effect that the products they design have on the consumer’s motivation to hold correct beliefs over preferences.

We examine how the degree of competition affects market outcomes in our setting. We start by comparing monopoly to competition when the consumer’s cognitive state is exogenous (i.e., the consumer is deterministically sophisticated or naive). In this case, we find that competition is an unambiguous improvement over monopoly: competition increases consumer surplus at no cost to market efficiency. This is because competition erodes profits and transfers these rents to consumers, providing them with all gains from trade.

Next, we compare cognitive equilibrium outcomes under monopoly and competition and show that the profit-reducing effect of competition can actually negatively impact on market outcomes. In particular, we derive the unique cognitive equilibrium outcome under monopoly and compare this to a natural cognitive equilibrium under competition. In this case, we show that total surplus is strictly higher under monopoly relative to competition; that is, monopoly can be strictly more efficient than competition when the consumer is able to transition from naiveté to sophistication. This occurs because competition erodes profits, which incentivizes competing firms to offer relatively inefficient products that are very attractive to a naive consumer in an attempt to earn profits. Instead, since the monopolist can earn profits, they are willing to offer a product more in-line with the consumer’s true preference.

These findings have important policy implications. Since monopoly is more efficient than competition when the consumer’s cognitive state is endogenously determined, alternative policies, such as lump-sum redistributions from a monopolist to consumers, can improve on competitive outcomes. As such, competition is not the most effective tool at mitigating poor market outcomes resulting from consumer naiveté. Instead, if one makes the standard assumption that cognitive states are exogenously determined, one reaches the conclusion that competition unambiguously improves market outcomes. Hence, policymakers should display caution when proposing competition as a one-size-fits-all solution to the issues created by consumers exhibiting behavioral biases if such biases are endogenously determined. As such, the findings of this paper constitute important novel predictions that warrant further empirical investigation.

The paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2 we discuss the related literature. In Section 3 we provide the details of the model. Section 4.1 investigates market outcomes when consumer’s cognitive state is exogenously determined. Section 4.2 allows for the consumer to endogenously transition from naiveté to sophistication and compares the cognitive equilibrium outcomes of monopoly to competition. Section 5 concludes. All proofs are provided in Appendix A.

2. Related Literature

There is a large literature investigating consumer naiveté in market settings. Some examples include work that looks at naiveté in self-control problems [8] and work in which consumers ignore hidden add-on prices [6,10,11,12]. A common finding in this literature is that competition does not correct the inefficiencies created by the presence of naive consumers, but often increases consumer surplus by transferring gains from trade from firms to consumers. This literature, however, assumes that naiveté is a fixed characteristic of the consumer. We contribute to this literature by showing that when the consumer’s cognitive state is endogenously determined, competition can strictly decrease efficiency.

There is a selection of papers that find that competition can have negative consequences on market outcomes when consumers are naive. Herweg and Rosato argue that competition can increase inefficiency when a deceptive firm enters the market to compete against a transparent retailer [13]. This relies on the fact that competing firms can create market segmentation by taking advantage of the consumer’s naiveté. In our paper, instead, all firms are identical and, as such, the environment is perfectly competitive. As such, we show that competition can be surplus-reducing even though all gains from trade are transferred from firms to the consumer. Jimenez-Gomez establishes that competition may reduce consumer welfare when firms can ‘phish’ consumers by introducing a wedge between their experienced utility and their decision utility [14]. This is because competition lowers prices, which can induce consumers to make make purchases that they otherwise should avoid. Instead, the driving force in our paper is that competing firms create large distortions in an attempt to earn profits, while a profit-making monopolist is more willing to align provision with true fundamentals.

This paper also relates to the literature on contract design with either naive consumers or other cognitive considerations. Salant and Siegel provide a model where a consumer is subject to framing effects that increase the attractiveness of products [15]. The authors consider a form of consumer protection that is ex-post in nature: the frame can wear off and the consumer can return the product. Instead, we consider a form of consumer protection that is ex-ante in nature: the consumer’s cognitive state is determined before they select a product and is determined as a function of the products offered. Moreover, we consider the role of competition while Salant and Siegel focus on the case of monopoly. Eliaz and Spiegler investigate how a monopolist would effectively screen agents that have private information regarding their degree of naiveté [16]. Instead, we focus on how market structure affects market outcomes in a complete information environment where the consumer can transition between naiveté and sophistication. Finally, Tirole provides a model where parties to a contract can choose to keep some default, potentially sub-optimal, contract or to invest in cognition to investigate whether the contract can be improved upon [17]. In their paper, the contracting parties hold a sophisticated understanding of the environment, so that no party is exploited in equilibrium. Instead, we speak to exploitation in markets as our consumer can endogenously end up misperceiving their preference.

The paper also relates to other notions of naiveté applied in other economic contexts. For example, receivers may naively interpret signals in communication settings [18,19]. Again, these papers model naiveté as a type of the receiver, while we consider the role of endogenous naiveté. Finally, Martin considers a naive buyer who does not properly understand equilibrium strategies in a strategic pricing game, but can acquire information about this strategy at cost [20]. Our model is similar in that our consumer may misperceive how they should behave, but is less likely to behave in this way the greater the benefits to avoiding doing so. Our focus, however, is on both the efficiency of, and the degree of exploitation in, the market, while Martin focuses on the informativeness of equilibrium prices.

Finally, the paper contributes to the literature on motivated beliefs (see [21] for a detailed review). This literature generally seeks to rationalize the underlying motivations for why an individual may hold biased, self-serving beliefs [22,23,24]. This paper, on the other hand, takes biased beliefs as given and instead focuses on whether the individual is motivated to correct this misperception. This allows us to explore how firms manipulate a consumer’s motivation to be sophisticated.

3. The Model

3.1. Formal Details

The Environment: There are profit-maximizing firms that each provide a finite menu of products to a consumer. A product is a bundle , where denotes the quality or level of provision of some good and is the price. Providing a product at quality q costs firm i, , where C is strictly increasing, strictly convex, differentiable, and . Let h denote the inverse of (the derivative of C), which exists since C is strictly convex4.

If the consumer chooses product from firm i, firm i earns profits equal to . Else, if the consumer does not purchase from firm i, firm i earns zero profits. Let denote the finite product menu designed by firm i and let denote the entire set of products that the consumer can choose from. We assume that the consumer chooses only one product from 5.

Consumer Preferences: The consumer decides whether to select a product from or not. If the consumer has preference parameter , the consumer values product according to

Instead, if the consumer does not purchase a product from , they receive reservation utility of zero, which is equivalent to selecting the product for all . Hence, we assume without loss of generality that .

Sophistication and Naiveté: The consumer will be in one of two cognitive states: they will either be sophisticated or naive. More precisely, assume that the true preference parameter of the consumer is given by . If the consumer is sophisticated (denoted by S), they understand that their true preference parameter is and, as such, value product x according to . Instead, if the consumer is naive (denoted by N), they misperceive their preference over products by overvaluing provision of the good relative to its price. Specifically, they perceive that their preference parameter is given by , , so that they value product x according to . We call the consumer’s degree of naiveté as it captures the extent to which a naive consumer misperceives their true preference. Notice that for any product with . Hence, the naive consumer over-values products relative to their sophisticated counterpart.

Endogenous Naiveté: The consumer is initially naive but can endogenously transition from naiveté to sophistication through an investment in cognition. If they do not choose to make this investment, then the consumer utilizes the misperceived preference to make decisions. Formally, let denote the cognitive investment decision of the consumer, where implies an investment in cognition (i.e., a decision to become sophistication). We assume that such an investment is costly: the consumer incurs a cognitive cost of if and only if they choose .

Suppose that the consumer faces menu of products . Let denote a product that the consumer in cognitive state selects; that is, . Then, the consumer’s true utility from choosing to be in cognitive state when facing menu is given by

where is an indicator function. It is optimal for the consumer to invest in cognition if and it is optimal for the consumer not to invest in cognition when .

Cognitive Equilibria: We now define the relevant equilibrium concept that we use to make predictions, which we call a cognitive equilibrium. To do so, let denote a selection rule for the consumer in cognitive state and a cognitive-investment strategy from an arbitrary menu . Let denote the expected profit of firm i when offering menu , given that the rest of the firms offer jointly menu and the consumer’s selection rules are given by , and cognitive strategy is . A notion of equilibrium in which the consumer’s cognitive state is endogenously determined is now defined.

Definition 1.

The tuple is a cognitive equilibrium if, for all finite menus of products ,

- (i)

- only if for ; and

- (ii)

- only if ,

and maximizes for each firm .

Essentially, a cognitive equilibrium is a subgame perfect equilibrium of a market game in which, first, each firm simultaneously designs a menu of products and, given the menu of products faced, the consumer decides whether or not to invest in cognition and makes a product selection given the realized cognitive state. Condition (i) of Definition 1 requires the consumer to only select products that are optimal from the perspective afforded by each cognitive state that may realize. Instead, condition (ii) requires that the cognitive-investment decision is determined optimally given how the consumer would behave in each cognitive state. The final requirement is that the product-menu provided by a given firm constitutes a best response to other firms’ menus given the consumer’s decision rules.

3.2. Efficient and Exploitative Good Provision

We now define the market outcome variables that are of interest in this paper. Let denote the maximal achievable total surplus when the preference parameter of the consumer is given by ; that is, . The maximizer of this problem is , so that is the efficient level of provision of the good if the consumer has preference parameter . Since the true preference parameter of the consumer is , we have the following natural definitions of both an efficient product and an efficient market.

Definition 2.

A product is efficient if . A market is efficient if it generates total surplus equal to .

Note that there always exists an efficient product that the consumer is willing to accept even if they are naive6. As such, the market can be efficient only if the consumer does not invest in cognition. Instead, if the consumer invests in cognition, the highest surplus that such a market can attain is .

Next, we define what is meant by consumer exploitation in our framework. Recall that the consumer can guarantee herself a reservation utility of at least zero by choosing the outside option. This leads to the following natural definition of consumer exploitation in the market.

Definition 3.

The market is exploitative if the true utility of the consumer is strictly lower than zero.

Definition 3 states the market is exploitative if the consumer earns true utility lower than their reservation level. This can happen either because the consumer naively chooses an exploitative product (i.e., one in which they overpay for provision) or because the consumer incurs cognitive costs that exceed the benefit of whichever product is selected under sophistication.

3.3. Discussion of Key Modeling Assumptions

We have modeled the consumer’s misperception in a relatively general way: the consumer simply over-values provision of the good relative to their true preference. This could be for a number of reasons. For example, the consumer may be subject to framing or advertising effects that make them over-value the product [15], the consumer may not be paying attention to certain factors that affect their preference for the good [25], or may have alternative self-serving motivations to hold biased beliefs (e.g., thinking that they are more likely to go to the gym as it allows them to feel motivated to get fit). We do not take a stand on precisely the reason for this misperception and instead focus on the consumer’s incentives to correct this bias through costly cognitive investment.

Regarding cognition, we have assumed the consumer has access to a very simple cognitive technology: if they invest in cognition they learn their true preference, , (i.e., become sophisticated), while if they do not make this investment they make decisions using the misperception, (i.e., stay naive). We do this to starkly illustrate how cognitive investment can serve as a bridge between naive decision-making and its sophisticated counterpart.

4. Results

4.1. Exogenous Cognitive States

We first present results for a benchmark model in which the consumer’s cognitive state is determined exogenously; that is, the consumer’s cognitive state is fixed at either sophistication or naiveté and the firms know the realization of this cognitive state. Equivalently, we solve for a cognitive market equilibrium where the consumer’s cognitive cost is either (i.e., the consumer is always sophisticated) or (the consumer is always naive). The first proposition describes the outcome under monopoly.

Proposition 1.

Under monopoly, a consumer in exogenously-known cognitive state selects

- (a)

- the efficient product if sophisticated; and

- (b)

- the inefficient product if naive.

According to Proposition 1, the consumer is provided an efficient level of the good when sophisticated and is over-provided the good when naive. This is intuitive since the consumer over-values the good when naive and so the monopolist increases provision in order to satiate this preference and extract extra rents. This results in exploitation of the naive consumer.

We now compare this outcome under monopoly to the competitive outcome. First, we derive the products selected by the consumer in each cognitive state in a competitive environment. To this end, suppose that there are firms that all know the consumer’s cognitive state. The following proposition describes the equilibrium outcome in this competitive environment.

Proposition 2.

Under competition, a consumer in exogenously-known cognitive state selects

- (a)

- the efficient product if sophisticated; and

- (b)

- the inefficient product if naive.

Proposition 2 states that, similar to the case of monopoly, provision is efficient to a sophisticated consumer but the good is inefficiently over-provided to a naive consumer. Thus, competition does not correct the inefficiency created by naive consumers. It does, however, affect the price that the consumer pays for provision. A full comparison of market outcomes under monopoly and competition are provided in the following proposition.

Proposition 3.

If the consumer’s cognitive state is exogenously known, then

- (a)

- total surplus under monopoly and competition coincide; and

- (b)

- consumer surplus is strictly higher under competition relative to monopoly.

Proposition 3 establishes that the degree of competition has no effect on market efficiency when the consumer’s cognitive state is exogenously determined. Specifically, under both monopoly and competition, a sophisticated consumer selects a product with efficient provision of the good, , while the naive consumer is over-provided the good at level .

The intuition for this result is as follows. Under both competition and monopoly, market forces incentivize the maximization of total surplus as if the consumer’s preference parameter was that which they actually perceive. In the case of sophistication, this results in efficient provision. Instead, when the consumer believes their preference parameter is greater than it is, the resulting provision in the market aligns with this misperception.

The main difference between monopoly and competition is the transfer the consumer makes to firms for this common level of good provision. Specifically, part (b) of Proposition 3 states that the consumer is strictly better off under competition relative to monopoly. This is because competition drives down the price of provision which, consequently, increases the gains from trade realized by the consumer. This effect is present regardless of whether the consumer is sophisticated or naive: all surplus (whether efficient or inefficient) accrues to the consumer under perfect competition.

In summary, one can conclude that competition unambiguously improves market outcomes when the consumer’s cognitive state is common knowledge. This is broadly consistent with findings in the behavioral economics literature that suggests that competition does not necessarily increase market efficiency in the presence of exogenously naive agents but, rather, serves to transfer (inefficient) surplus from firms to consumers [6,8]. As such, competition is an effective policy tool to mitigate naiveté-based exploitation in this case. When the consumer’s cognitive state is endogenously determined, however, we will see that such a clear dominance relation cannot be established. We explore this in the next section.

4.2. Cognitive Equilibrium

In this section, we consider the model described in Section 3 in which the consumer’s cognitive state is endogenously determined. We first derive the unique cognitive equilibrium outcome under monopoly. Then, we derive a natural cognitive equilibrium under competition and, finally, compare monopoly and competitive cognitive equilibrium outcomes.

4.2.1. Monopoly

We first consider the case where there is monopolistic provision of the good to the consumer. Since the consumer is only ever in one of two cognitive states, the monopolist needs to design only two products: which the consumer selects as a sophisticate, and which the consumer selects as a naif. Moreover, it is without loss of generality to assume that the consumer does not invest in cognition; that is, the consumer is incentivized by the monopolist to remain naive and select product . This is because the optimal product to offer a sophisticate is (derived in Proposition 1), which also satisfies the participation constraint of the naive consumer7. As such, we can write the monopolist’s optimization problem as follows:

subject to

Constraints (IC-S) and (IC-N) ensure that the sophisticated and naive consumers, respectively, are willing to select the products designed for them. Instead, constraint (No-Think) ensures that the consumer does not invest in cognition but, rather, makes their product choice holding biased beliefs. The following proposition describes the product that the consumer selects in the cognitive equilibrium under monopoly.

Proposition 4.

Let and . The product selected by the consumer in the cognitive equilibrium under monopoly, , has

The consumer is exploited for all cognitive costs .

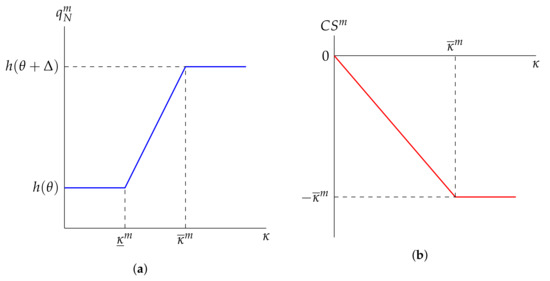

Proposition 4 describes the product that the consumer selects in the unique cognitive equilibrium outcome under monopoly. The left panel of Figure 1 illustrates the level of good provision, , to the consumer as a function of cognitive costs, . When is large, the monopolist provides the same product that is provided to an exogenously naive consumer (Proposition 1). Instead, when is small, the consumer is provided with an efficient level of the good, . Finally, for intermediate levels of , provision in the monopolist’s optimal product is strictly in-between the levels provided to exogenously naive (i.e., ) and exogenously sophisticated (i.e., ) consumers. Thus, provision to an endogenously naive consumer is always closer to the efficient level than to their exogenously naive counterpart.

Figure 1.

Graphical depiction of the cognitive equilibrium outcome under monopoly. Panel (a) displays how good provision, , varies with cognitive cost , while panel (b) displays how consumer surplus, , varies with cognitive cost .

The intuition for this result is as follows. There are two main constraints that the monopolist must consider when designing the optimal product: (1) the participation constraint of the naive consumer and (2) the constraint that ensures the consumer does not invest in cognition. The participation constraint pushes provision towards the naif-optimal level, , as it utilizes the consumer’s misperception, . Instead, the (No-Think) constraint pushes provision towards the efficient level, , as it is determined by the consumer’s true preference parameter, . When is sufficiently large, the former dominates and the consumer is over-provided the good. Instead, when is sufficiently small, the latter dominates and provision is efficient. Finally, for intermediate both constraints bind and optimal provision falls between these two levels.

Proposition 4 also states the consumer is exploited as long as the cost of becoming sophisticated is strictly positive. Thus, the monopolist is still able to take advantage of the fact that the consumer is bounded in their rationality. At the same time, the fact that the consumer can transition to sophistication does reduce exploitation, at least when the cost of cognition is small. This is because the threat of becoming sophisticated forces the monopolist to decrease exploitation in order to depress incentives to invest in cognition. The right panel in Figure 1 illustrates consumer surplus in the cognitive equilibrium outcome under monopoly as a function of .

4.2.2. Competition

We now consider the case where firms compete for the consumer’s attention. We focus on a natural cognitive equilibrium under competition, which we call the -cognitive equilibrium. Recall the products and that are offered to sophisticates and naifs, respectively, in a competitive environment with exogenously known cognitive states (Proposition 2). The following proposition establishes that it is also a cognitive equilibrium under competition for each firm to offer precisely the menu of products .

Proposition 5.

Let . It is a cognitive equilibrium under competition for all firms to offer the menu of products . In this equilibrium, the consumer:

- (a)

- invests in cognition and selects for ; and

- (b)

- does not invest in cognition and selects for .

The market is never efficient in this cognitive equilibrium and the consumer is exploited if θ is sufficiently small.

The -cognitive equilibrium under competition is a natural equilibrium to focus on as the consumer is provided only products that are optimal given her cognitive state, subject to firms earning non-negative profits. As such, it is likely that this would constitute a natural long-run outcome of competition with endogenous cognitive states.

In this equilibrium, the product is optimal for the consumer to choose since their true preferenece parameter is . However, is more attractive under misperception . As such, the consumer becomes sophisticated and selects only when is small. Instead, when is large, investment in cognition is not of sufficient value and so the consumer remains naive and selects product . The intuition for why this constitutes an equilibrium is as follows. Competition erodes profits on any viable product to zero which, in turn, incentivizes the competing firms to offer products that are maximally attractive to the consumer in an attempt to earn positive profits: to a sophisticated consumer and to a naive consumer. Since no other products exist that earn positive profits that the consumer values more, it follows that this is a cognitive equilibrium.

Recall that the consumer was always exploited in the cognitive equilibrium under monopoly (Proposition 4). Proposition 5 establishes that, while exploitation is less prevalent under competition, it is not necessarily eliminated. Specifically, this occurs when the consumer does not particularly value the good ( is small). In such a situation, the consumer is exploited because (1) they invest in cognition and select a good that is less valuable than the cognitive cost incurred or (2) they do not invest in cognition and instead overpay for the good relative to its utility generated under their true preference.

Finally, we conclude by noting that the market is never efficient in the -cognitive equilibrium under competition. This is because the consumer either selects the inefficient product when is large, or selects the efficient product only after incurring wasteful cognitive cost when is small. Since the cognitive equilibrium outcome under monopoly was sometimes efficient (Proposition 4), it follows that, at least in some region of the parameter space, monopoly can outperform competition in terms of total surplus maximization.

4.2.3. Comparing Monopoly to Competition

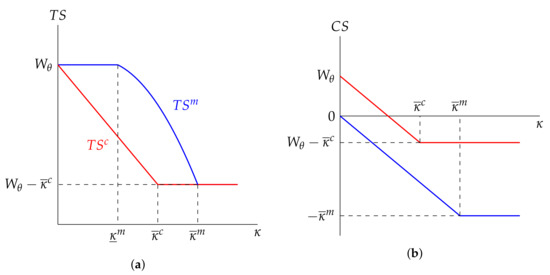

In the previous section, we analyzed a natural cognitive equilibrium under competition and showed that competition tended to decrease exploitation but generate inefficiencies relative to monopoly, at least in some regions of the parameter space. The following proposition establishes that these observations hold in general when comparing the monopoly cognitive equilibrium outcome to the -cognitive equilibrium under competition.

Proposition 6.

Comparing the cognitive equilibrium under monopoly to the -cognitive equilibrium under competition:

- (a)

- monopoly is more efficient; and

- (b)

- consumer surplus is higher under competition.

Figure 2 displays graphically how both total surplus (left-hand panel) and consumer surplus (right-hand panel) vary with under both monopoly and competition. As one can see, total surplus is always higher under monopoly; strictly so when cognitive costs are relatively small. Instead, consumer surplus is larger under competition at every level of .

Figure 2.

Graphical comparison of cognitive equilibrium outcomes under monopoly and competition. Panel (a) compares total surplus as a function of cognitive cost , while panel (b) compares consumer surplus as a function of cognitive cost .

The intuition for this finding is as follows. As discussed in the previous section, competitive pressure erodes profits which induces firms to offer products that are maximally attractive to the consumer. For the naive consumer, since this product is aligned with biased beliefs, this implies that they are offered is relatively inefficient. The consumer then either selects this inefficient product or incurs cognitive costs to avoid doing so. The monopolist, instead, is able to earn profits and, as such, does not face as strong an incentive to satiate the naive consumer’s misperceived preference. Rather, they offer the consumer a more efficient product in order to reduce incentives to invest in cognition. It follows that total surplus is higher under monopoly. At the same time, competition transfers all gains from trade from firms to the consumer, while the monopolist is able to extract all gains from trade. This transfer makes the consumer strictly better off in the competitive environment, even though the total gains from trade are smaller in aggregate.

While the introduction of consumer surplus decreases exploitation, it (1) does not necessarily eliminate it (Proposition 5) and (2) it comes at the cost of lower aggregate gains from trade (Proposition 6). This implies that there may exist alternative policies that are more effective than competition policy at ameliorating naiveté-based discrimination. Indeed, since monopoly leads to higher total surplus, a policymaker can find a lump-sum transfer (which does not distort good provision) from the monopolist to the consumer such that monopoly actually Pareto dominates competition; that is, both profits and consumer surplus are higher under monopoly after the imposition of transfers than the competitive outcome. This stands in contrast to the setting in which the consumer’s cognitive state was exogenously determined, where the competition dominated monopoly across all market outcomes. As such, allowing the consumer to endogenously transition between cognitive states has important policy implications.

As stated previously, it is commonly found that competition does not neccessarily increase market efficiency in the presence of exogenously naive consumers [6,8]. We strengthen this finding by showing that increasing competition can actually strictly decrease total surplus when the consumer is endogenously naive. This finding also fits with the idea of a “phishing” equilibrium, as proposed by Akerlof and Shiller [26]. The idea of a phishing equilibrium is that competitive environments are brutal for firms that are trying to earn profits. This may lead firms to compete along more nefarious dimensions (like taking advantage of consumer naiveté), rather than by offering better products. Here, we see this quite starkly. It is precisely this competitive pressure which erodes profits earned on efficient products and, thus, induces firms to offer inefficient products attractive only due to the naif’s biased beliefs. Instead, the monopolist does not face such pressure because he is able to earn profits on products aligned with true underlying fundamentals.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

This paper has explored a market setting in which firms design products for a consumer that holds either a naive or sophisticated understanding of their preference. The novel contribution of the paper was to introduce the idea that sophistication for the consumer should come only through costly cognitive investment. As such, the products that are designed for the consumer determine whether they are motivated to become sophisticated. To this end, we introduced the solution concept of cognitive equilibrium, in which the cognitive state of the consumer is endogenously determined as a function of the products present on the market.

We explored the role that the degree of competition plays in determining market outcomes. We showed that, when the market is in cognitive equilibrium, monopoly could actually outperform competition in terms of market efficiency. This is because competitive pressure incentivizes firms to offer relatively inefficient products that the naive consumer finds attractive in an attempt to earn profits. The large inefficiency then results from the fact that the consumer either selects this relatively inefficient product or invests in wasteful cognition to avoid doing so. The monopolist, instead, can earn profits on more efficient products and, therefore, does not find it optimal to distort provision to as large an extent. We believe that this novel interaction between market outcomes and the determination of the consumer’s cognitive state warrants further empirical investigation to understand whether the mechanism we have identified exists in the data.

We emphasized the importance of modeling the consumer’s cognitive state as being endogenously determined. Specifically, we showed that if we model the consumer’s cognitive state as a fixed characteristic, then one would conclude that competition unambiguously improves market outcomes. This is not the case when the consumer can transition between cognitive states. As such, policy-makers should be careful when proposing competition as a ‘one-size-fix-all’ solution for dealing with poor market outcomes resulting from consumer naiveté. Rather, other policies may be more suitable. For example, we have already identified that lump-sum redistributions from a monopolist to consumers can improve upon competitive outcomes. However, other policies, such as directing resources towards educating consumers to identify exploitation in the market may also constitute more effective policy than competition. Such policies would serve to decrease cognitive costs, which always leads to an increase in both total and consumer surplus.

Naturally, there are some limitations to the study that we have conducted. First, we have considered only two cognitive states: naiveté and sophistication. In reality, the consumer may exhibit a richer set of cognitive states which include the possibility of partial awareness of any preference misperception [3]. One could extend the notion of cognitive equilibrium to more cognitive states but should expect this to only minimal impact on the model’s predictions. Second, we have assumed that the consumer’s cognitive ability (i.e., cognitive costs) is known to each firm, while this may not be such an unreasonable assumption in the world of ‘big data’, in reality firms may still face some residual uncertainty over the cognitive ability of a particular consumer. Future research should investigate whether such asymmetric information considerations significantly impact on our findings.

We conclude by commenting briefly on the cognitive equilibrium concept we have introduced. While we have used this notion to explore consumer naiveté in a goods market, it is a portable concept that can be applied to any other environment where individuals may behave in a naive fashion, such as when needing to predict their own future behavior, when interpreting signals in communication settings, or in models of over-optimism. Future work will apply the concept of cognitive equilibrium in such settings. This will allow us to understand both the settings in and extent to which assuming that cognitive states are determined exogenously is a restrictive assumption, while also identifying situations where predictions are sufficiently different so that one must consider whether cognitive equilibrium constitutes a more suitable solution concept.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Proof of Proposition 1.

Suppose the consumer exogenously believes that their preference parameter is . The monopolist offers a product that solves the problem

subject to . Clearly, the consumer’s participation constraint binds and the first order condition for an optimum is . Thus, sophisticates are offered the product , while naifs are offered the product . □

Proof of Proposition 2.

Suppose that there are firms. We show that the consumer with preference parameter must select the product . First, we show that any product selected by the consumer with positive probability must earn zero profits. Let denote the set of products that the consumer selects with positive probability and take . Suppose, by contradiction, that . Note that at least one firm must make profits strictly lower than . Suppose this firm offers product . Then is strictly preferred by the consumer to . Moreover, for sufficiently small, this product earns profits arbitrarily close to . As such, constitutes a profitable deviation. It follows that for all .

Now, we show that the consumer selects a product with provision . Suppose instead the consumer selects a product with . Then the consumer with preference parameter receives surplus equal to . Consider a firm that instead offers the product with and , where . This gives the consumer utility which is strictly larger than for sufficiently small. Moreover, the deviating firm earns profits equal to . Combining this with the fact that firms earn zero profits in equilibrium, a consumer with preference parameter must select product . □

Proof of Proposition 3.

Part (a) of the proposition is clear: regardless of the degree of competition, a sophisticated consumer selects an efficient product, while a naive consumer selects an inefficient product at provision level . Hence, total surplus is equal to for under both monopoly and competition. Part (b) follows from the fact that for (since strictly increases in and equals zero when ). Hence, the transfer made by the consumer is strictly larger under monopoly relative to competition. □

Proof of Proposition 4.

Let denote the optimal product selected by the consumer if in cognitive state . First, note that . If not, then it holds that . Then, the monopolist could offer the products which, for sufficiently small , satisfy the incentive compatibility constraints and (No-Think). Thus, . Moreover, it is without loss of generality to assume . Indeed, if is a part of an optimal menu, then offering instead satisfies all constraints (since ) without affecting the monopolist’s profits (since is never selected in equilibrium).

The preceding argument implies the monopolist offers only a single product. This product solves the optimization problem

subject to and . Let denote the Lagrange multiplier on the first constraint and the multiplier on the second. The Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions are sufficient for a global optimum since this is a strictly concave problem with linear constraints and are given by

where with strict inequality only if the corresponding constraint binds.

We have that and is a solution, so that , if and only if or . Instead, we have that and , so that , if and only if or . Finally, if , both and so that both constraints bind and .

Finally, we have that consumer surplus under monopoly (denoted by ) is equal to

Clearly, this is strictly less than zero as long as and , so that the consumer is always exploited in equilibrium under monopoly. □

Proof of Proposition 5.

It is simple to argue that every firm offering the menu of products constitutes a cognitive equilibrium under competition. Indeed, by definition, maximizes the utility of the consumer in cognitive state . Hence, there does not exist an alternative product that the consumer would be willing to select in either cognitive state that earns strictly positive profits.

Consumer surplus in this equilibrium, , is given by

Since and , it follows that for sufficiently small (since implies that and ). □

Proof of Proposition 6.

(a): Let denote the total surplus in the cognitive equilibrium under competition described in Proposition 5, which is given by

Instead, from Proposition 4, total surplus under monopoly (denoted ) is given by

First, note that if and only if , which holds since . Comparing (A4) and (A5), if , then total surplus under monopoly and maximal total surplus under competition coincide. Instead, if , since monopoly is efficient in this region and competition is never efficient.

The final case to consider is . If , we have that

since and is strictly decreasing in z for . Instead, if , we have that while, under monopoly, the consumer receives true surplus equal to . Thus, the proof is complete if the monopolist earns profits larger than . This holds due to the fact that

where the first inequality follows from the fact that and is strictly increasing in z for .

(b): Let denote consumer surplus in the -cognitive market equilibrium under competition, which is given in (A3), and let denote consumer surplus under monopoly, which is given in (A2). For , we have that

since . Instead, for , we have that

where the second last inequality holds if . Thus, . □

Notes

| 1 | Naiveté has been used to explain why people procrastinate [1,2,3], over-estimate future gym attendance [4,5], struggle to avoid hidden add-ons or fees [6], and deviate from their self-set goals [7]. It has also been used to explain market-based phenomena. For example, DellaVigna and Malmendier use naiveté to explain the prevalence of sign-up bonuses coupled with above marginal cost pricing for leisure goods (such as credit cards) and the prevalence of high sign-up costs with lower-than marginal cost pricing for investment activities (such as attending a health club) [8]. |

| 2 | For example, all the papers cited in Footnote 1 make this assumption. |

| 3 | For example, in their influential book “Thinking Fast and Slow”, Kahneman describes a dual-system of decision-making in which System 1 is a fast, intuitive thinker potentially prone to bias and System 2 is a slow, contemplative thinker that effectively optimizes [9]. He argues that, most of the time, System 1 is in control of our decisions but System 2 will take over when the situation is warranted. |

| 4 | This will be useful notation for describing equilibrium provision of the good to the consumer. |

| 5 | Since each is finite, is also finite. As a result, the consumer will always be able to make an optimal choice from . |

| 6 | For example, the product is such that . |

| 7 | Indeed, the utility of a naive consumer from product is

|

References

- Akerlof, G.A. Procrastination and Obedience. Am. Econ. Rev. 1991, 81, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue, T.; Rabin, M. Doing it Now or Later. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, T.; Rabin, M. Choice and Procrastination. Q. J. Econ. 2001, 116, 121–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaVigna, S.; Malmendier, U. Paying Not to Go to the Gym. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 694–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acland, D.; Levy, M.R. Naiveté, Projection Bias, and Habit Formation in Gym Attendance. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaix, X.; Laibson, D. Shrouded Attributes, Consumer Myopia, and Information Suppression in Competitive Markets. Q. J. Econ. 2006, 121, 505–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Self-Control and Optimal Goals: A Theoretical Analysis. Mark. Sci. 2009, 28, 1027–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaVigna, S.; Malmendier, U. Contract Design and Self-Control: Theory and Evidence. Q. J. Econ. 2004, 119, 353–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heidhues, P.; Koszegi, B. Exploiting Naivete about Self-Control in the Credit Market. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 2279–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidhues, P.; Koszegi, B.; Murooka, T. Exploitative Innovation. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2016, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidhues, P.; Koszegi, B. Naiveté-Based Discrimination. Q. J. Econ. 2017, 132, 1019–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweg, F.; Rosato, A. Bait and Ditch: Consumer Naïveté and Salesforce Incentives. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2020, 29, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Gomez, D. Nudging and Phishing: A Theory of Behavioral Welfare Economics. 2018. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3248503 (accessed on 20 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Salant, Y.; Siegel, R. Contracts with Framing. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2018, 10, 315–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliaz, K.; Spiegler, R. Contracting with Diversely Naive Agents. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2006, 73, 689–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirole, J. Cognition and Incomplete Contracts. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009, 99, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, M.; Squintani, F. Naive Audience and Communication Bias. Int. J. Game Theory 2006, 35, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Perturbed Communication Games with Honest Senders and Naive Receivers. J. Econ. Theory 2011, 146, 401–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. Strategic Pricing with Rational Inattention to Quality. Games Econ. Behav. 2017, 104, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénabou, R.; Tirole, J. Mindful Economics: The Production, Consumption, and Value of Beliefs. J. Econ. Perspect. 2016, 30, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénabou, R.; Tirole, J. Self-Confidence and Personal Motivation. Q. J. Econ. 2002, 117, 871–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eil, D.; Rao, J.M. The Good News-Bad News Effect: Asymmetric Processing of Objective Information About Yourself. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2011, 3, 114–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.H.; Huang, W.; Zhao, X. Motivated False Memory. J. Political Econ. 2020, 128, 3913–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C.A. Implications of Rational Inattention. J. Monet. Econ. 2003, 50, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G.A.; Shiller, R.J. Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).