1. Introduction

This paper aims to highlight a particular legislative tool in the public contracts sector, the so-called “White List”. This instrument was introduced by the legislator to preserve clients from disputes included in the production cycle, called “Bad Company”. These disputes in some cases have also caused serious damage to the contracting company in the public sector. In the current setting, the “White Lists” are lists of companies set up at each Italian Prefecture. These lists include firms working in sectors considered to be at the highest risk of mafia infiltration, and they must register. According to the latest legislative provisions, registration on these lists has become mandatory for companies that want to participate in invitations to tender for the award of Public Contract. The aim of the legislator, with the introduction of the “White List”, is to achieve a balance of interests: suppressing crime and protecting the public interest in the exact conduct of procedures and the fulfilment of contracts.

In this paper, we propose an economic and legislative view of the “White List” and use descriptive analyses to ask some questions, such as what can, and must, firms do before registration on the lists? Can the “White List” represent a valid tool to contrast mafia and an incentive for companies that participate in public tenders?

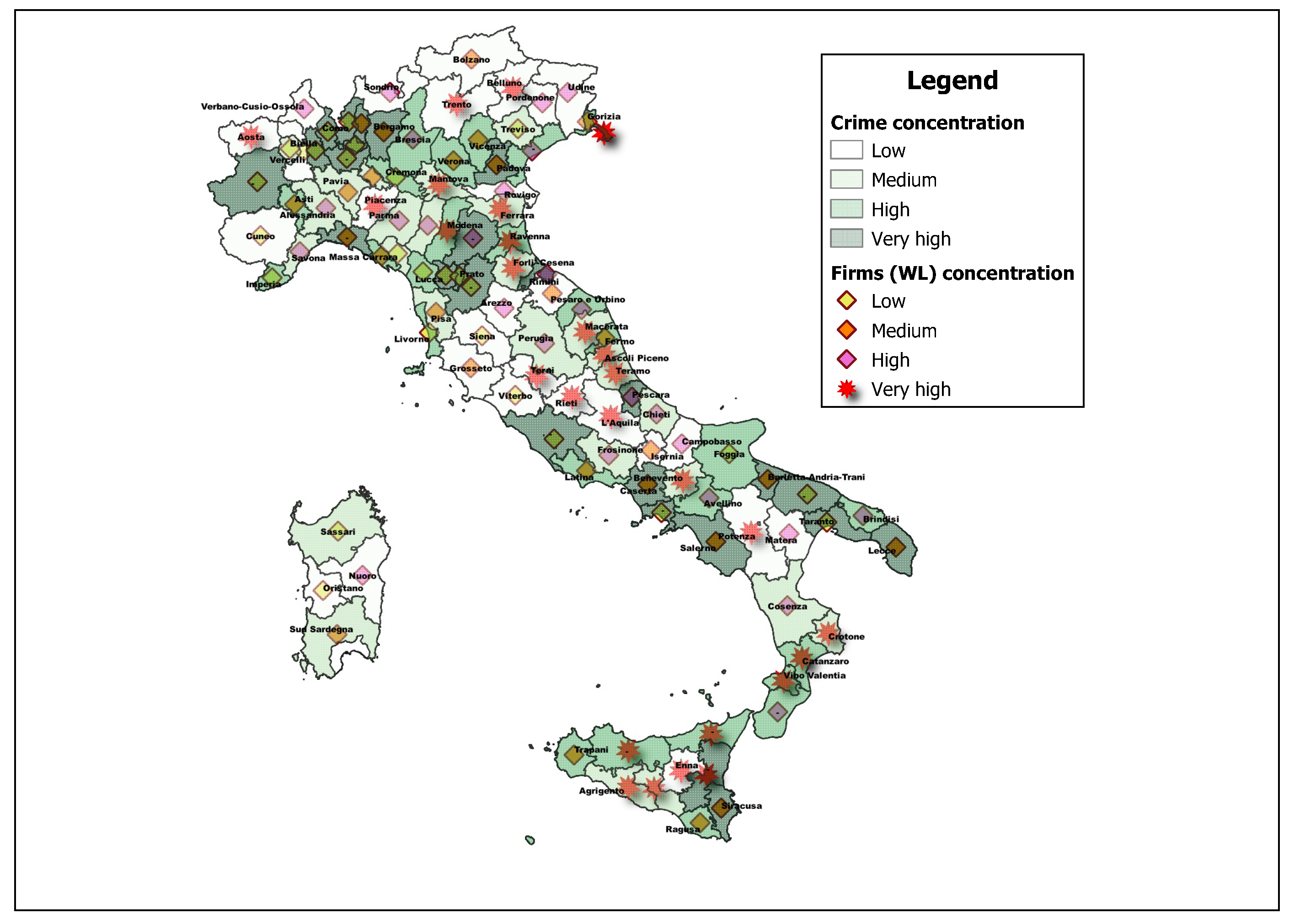

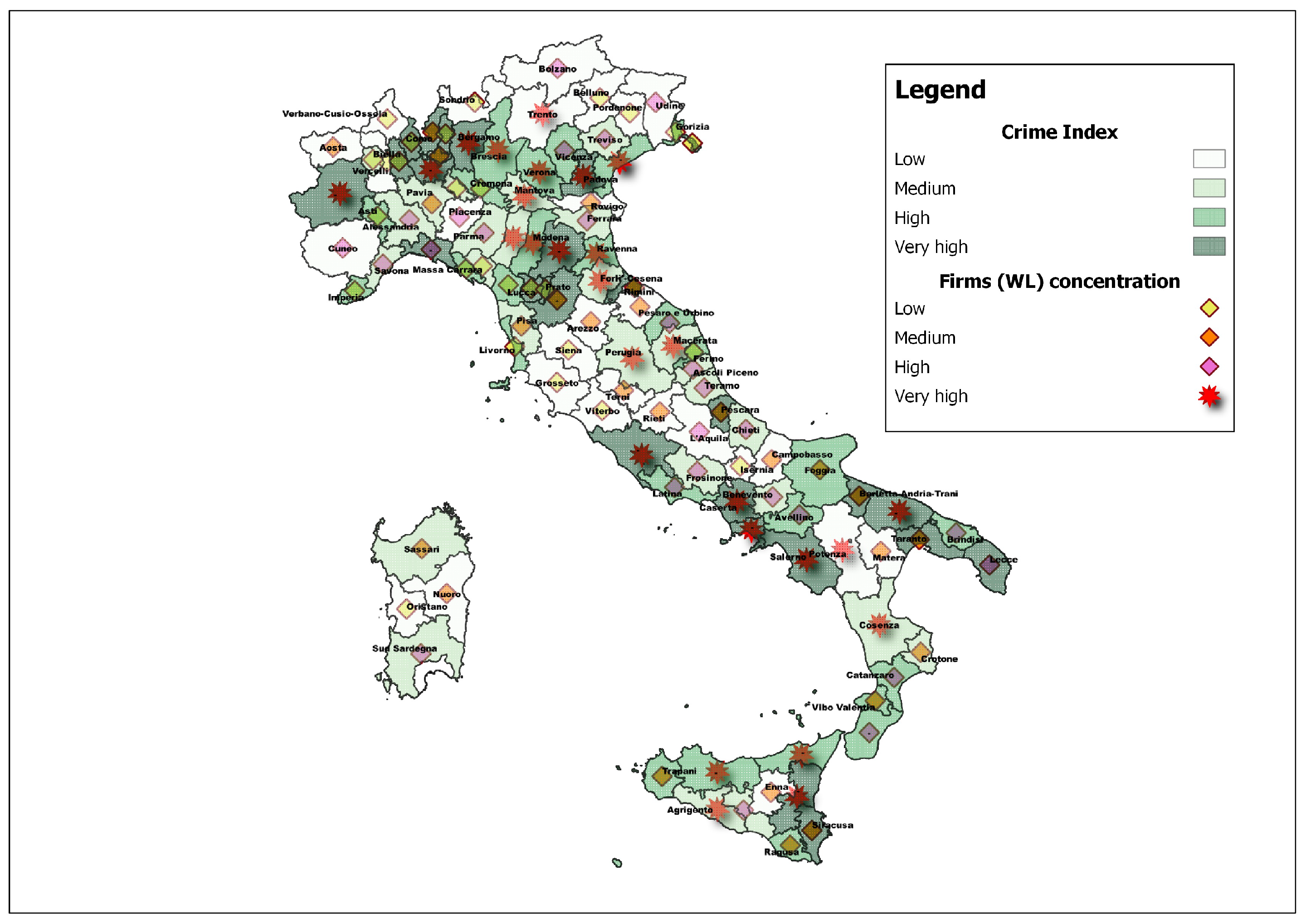

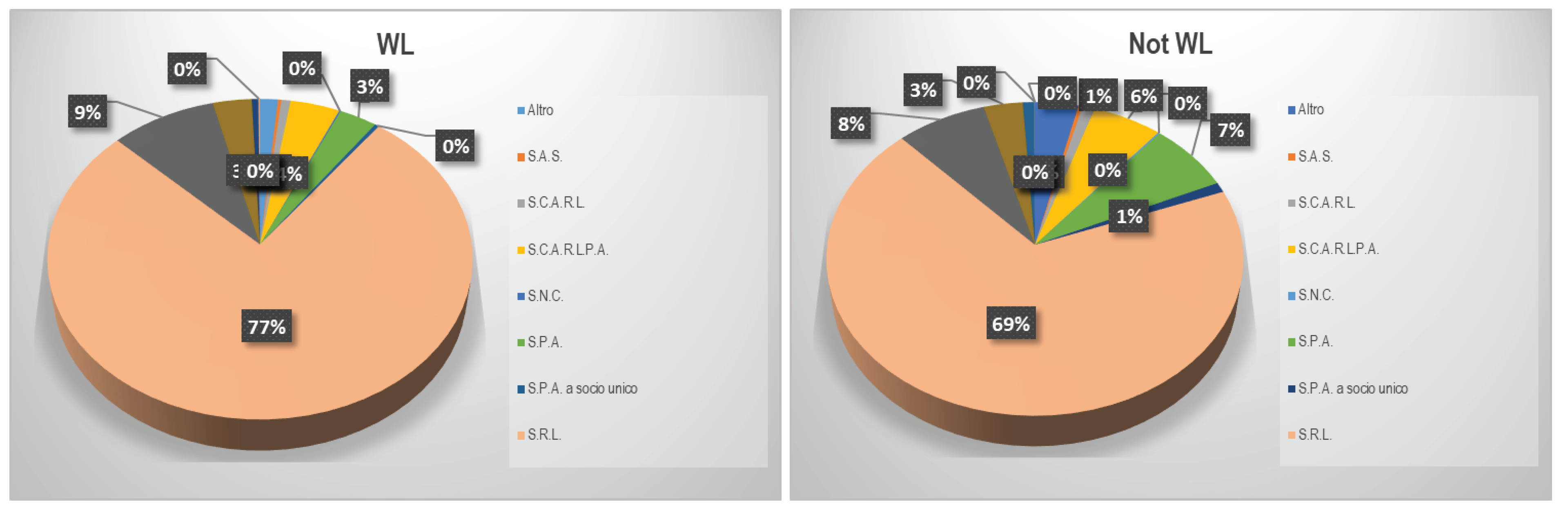

The issues of this project are constantly evolving because of its innovative nature, and this research represents the turning point of a series of partial explorations. The economic literature has not yet carried out any significant studies on these new instruments and, for this reason, it is necessary to expose the provisions of the law and its economic application. We propose a descriptive comparison between the enterprises that possess this instrument and the enterprises that do not possess the inscription in the prefecture lists also. The statistical descriptive analysis was conducted on two levels, the first on all the firms belonging to the “White List”, and the second on a representative sample of such firms. Using some performance indicators, we tried to compare two samples of firms in the period 2013–2020. The results, although preliminary, represent a valid starting point for deepening the issue of the “White List” as an essential tool for the certification of legality for businesses. The results show that, compared to the selected sample of firms belonging to the same sector, the “White List”’s firms are certainly smaller in terms of size and have better profitability and a lower recourse to third-party capital. Furthermore, to understand if the “White List” could represent a valid tool for overcoming the obstacles on the part of companies to participate in public tenders, especially in sectors characterised by strong roots in criminal organisations, we initially thought of mapping these companies with georeferencing techniques and observing whether they are located in areas with a high or low concentrations of crime. The results show that the highest concentration of firms on the “White List” are found in those territories where the concentration of crime is lower, except for the provinces of the Apulia region (in particular Crotone, Catanzaro and Vibo Valentia) and the Sicily region (Messina, Palermo and Catania). These findings are the result of descriptive comparisons, and certainly to an attentive reader they can be biased. In fact, registration on the White List is voluntary, and it is possible that the firms that request registration on the “White List” are the ones that have the best performance, not that the firms perform better because they are on the “White List”. This work does not aim to analyse the causal relationship between the certification of legality and business performance, but its goal is to contextualize this instrument of legality in the Italian business system, in particular, to understand where the White List’s firms are located, their characteristics and the context in which they operate.

Before deepening the quantitative aspect, it is necessary to frame the

“White List” tool starting from the original regulations in the field of instruments devoted to fighting against organised crime [

1].

At first, the definition of the term “crime” related to the economic context dates to 1940 when the American criminologist E.H. Sutherland spoke of “economic crime”. Economic crime or criminal entrepreneurship is defined as unlawful behaviour by economic operators in an organisation, typically a business [

2], but it should be remembered that “there is no generally accepted definition of economic crime, nor a distinct segment of theoretical and practical literature on economic crime” [

3]. It may be good to focus on specific aspects of the phenomenon when considering formulating a study instrument. Early studies focused mainly on game theory [

4], although not much later some scholars argued that economic instruments and models could be essential to the evaluation of criminal behaviour and the search for anti-crime strategies [

5], as well as the creation of a model of choice between legal and illegal activity [

6], adopted in a state of uncertainty. Many reflections underline the positive interrelationship between economic growth and the spread of economic/administrative crime/illegality. Schneider and Enste [

7] point out that the presence of irregular economies also means higher consumption in favour of the legal economy. In contrast, Choi and Thum [

8] point out that the irregular economy is predominantly complementary, and not a substitute for the legal one. Both theories tacitly accept the phenomenon. However, one of the most important aspects that the theoretical framework provides us with is that the tolerance of illegal behaviour and the ineffective fight against the violation of the rules leads to a reduction in confidence in the market and the state, and favours the persistence of mafias [

9]. In this context, we first focus on the public economic perspective and public procurement. Public procurement is considered by the legislator a strategic instrument, and it implements a more innovative and more inclusive system at European and national and regional levels [

10] in compliance with the principles of transparency, economy and equal treatment. The legislation on public procurement with the legislative decree 50/2016 imposes specific behaviour on the subjects who meet the Public Administration or the contracting authority. Compliance with procedural rules does not necessarily guarantee the continuation of the expected result in the public sector but, on the other hand, the public sector can select the bidder in a more economically advantageous manner for the administration, and ensure particularly necessary valuation in the public sector, such as the performance of the companies and the anti-mafia valuation. Many contributions from the economic literature are devoted to the analysis of how the private bidder is selected in public procurement. There are three variables to consider: (i) the subject matter of the contract; (ii) constraints on the action of the PA; (iii) the objectives that the administration intends to achieve [

11], and this process ensures that the choice is made optimally. This mechanism overcomes the asymmetric information between PAs and enterprises and intervenes in what is known in the economic literature as the ’allocative efficiency’ of the auction mechanism [

12]. In short, the PA aims to evaluate, select and choose the private bidder who complies with the law, but it is not the only request. In fact, in the literature on the most appropriate choices about public procurement [

13,

14,

15,

16], the principle of reputation was first introduced in the 1990s by Steven Kelman. Kelman (1990) argues that the failures in public are the consequence of a bad decision taken at the government level. For example, at a time when comprehensive regulation was being introduced to prevent corruption, it became a rule and, at the same time, the regulatory framework has become more complex and articulated. These failures are labeled by Kelman as a direct consequence of the rules in favour of open competition in public procurement and suggested that the legislature never introduce so-called negative rules but should introduce set out that respect the public action. It, therefore, argued that more discretionary standards should be used in the bidder selection process, considering the past performance of potential suppliers. Carroll [

17] in the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) literature talks about four social responsibilities of companies, and the “legal” one consists precisely of compliance with local, national, and international laws. In this way, the company is increasingly interested in demonstrating its “legality”: it becomes a strategic choice aimed at improving reputation [

18] and consequently also performance. To promote competition, it is important that enterprises respect the legal principles and adopt contagious behaviour that enhances their reputation [

19].

While, on the one hand, we considered the way in which companies act, it is necessary to define how the public sector reacts and what instruments it proposes. Public intervention to combat illegalities is essentially expressed in ex post activities, repression and the punishment of crimes already committed. Recently, the public economy has implemented three valuable instruments for the suppression crime and the promotion of legality: Rating di Legalità, Rating d’Impresa and White List.

Rating di Legalità was designed as an ex-ante intervention, to encourage economic operators, through a series of economic benefits and reputation, to have respect for the law. Stronger are the economic incentives linked to the adoption of legal behaviour, and the deterrence of illegal behaviour is more effective [

20]. The

Rating di Legalità is valid for two years. The literature collected so far is characterised by the brevity of the observations available, so much so that we have only been able to analyse the economic incentives relating to the legal effect determined by the performance of businesses. In particular, the study conducted by Alfano et al from 2019 to 2016 made it possible to verify in the context of Italy that the impact exerted on the

Rating di Legalità is particularly important in Central and Southern Italy: certifying legality is a sign of correct behaviour.

The Rating d’Impresa is a particular tool, introduced by the National Anti-Corruption Regulatory Authority (ANAC). This tool used for measuring the reliability of firms was initially introduced compulsorily with a series of indicators to support it. ANAC, based on an evaluation system that rewarded companies on the basis of their behaviour both in the phase of participation in a tender and in the execution of a public contract, and assigned them a score. The higher the score, the greater the advantages that can be obtained for the purpose of participating in a public tender. The scoring system to assign the rating consists of 40% reputational requirements and 60% of the performance obtained in the execution of public contracts in the last five years, issued by the PAs.

Finally, the “White List” originated in 2011 as an experimental project (cc. dd. “lists of virtuous enterprises”) designed to solve the intrusion of crime and corruption into particular activities considered sensitive. Subsequently, to speed up and simplify administrative procedures in terms of anti-Mafia control, they were established at the national level to promote legality in the public sector and the context of public contracts. Currently, the “White List” is divided into 10 sections referring to specific sectors, mostly dedicated to public construction works and waste disposal. ANAC, with Resolution No. 48 of 29 May 2019, specified that “inclusion in the “White List” is a real subjective requirement for the company that intends to participate in the tender, the failure of which therefore determines the inability to contract with the public administration”. This statement eliminates any previous doubts: there is an obligation to consult the “White List” on the one hand (for contracting stations) and the obligation to register on the other (for the bidders participating in the tenders). The aim is to achieve a balance of interests: to pursue public security and to suppress crime, and to protect the public interest in the exact conduct of procedures and the fulfilment of contracts.

From the starting point of traditional criminal repression, we have witnessed a significant expansion of crime suppression through the help of the administrative instruments that realize a prevention policy. The basic idea is to introduce

“Rating di Legalità”,

the Rating d’Impresa and the

“White List” as preventive instruments to support transparency: these, in fact, inevitably play a role of promoting the culture of legality [

21] The paper is organised as follows. The next section presents the legislative context in which the instrument of the

“White List” operates.

Section 3 describes the data and methodology,

Section 4 presents the results of the descriptive statistics, and

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. The “Lists of Virtuous Companies” as a Tool for Anti-Mafia Controls

It is recognised that the Italian territory has been fighting for a long time against crime and corruption and this aspect has affected every situation and circumstance. Originally, the “White List” was created as an experimental project designed to solve problems relating to the assignment of works and the supply of some activities considered particularly sensitive. These are specific contexts such as: (a) post-earthquake reconstruction in Abruzzo; (b) the extraordinary prison plan; (c) the works relating to the 2015 Milan EXPO; (d) post-earthquake reconstruction in Emilia. Lists of virtuous enterprises were created to combat the mafia phenomenon. The logic was to guarantee to those subjects who voluntarily underwent rigorous checks on the transparency of the organisational and functional structures, as well as the control of all contribution and tax obligations and for which the traceability of financial flows was possible, a series of reward incentives in terms of preference in awarding the planned works. The main requirement derives from the observation that some territories tend to absorb realities steeped in corruption. The Legislative Decree 159/2011, the “Anti-Mafia Code ”, provides for two different types of anti-mafia documentation: anti-mafia communication and anti-mafia information. The Anti-Mafia Code outlines, in art. 83, paragraph 1, the subjects who must acquire the anti-mafia documentation before being able to proceed with the stipulation of contracts and subcontracts relating to works, services and public supplies. The legislator recognizes the need to understand what relationships exist between these companies and the mafia infiltrations. With the Development Decree, the legislator makes effective the use of “White List”s to make anti-mafia controls more efficient. A list of suppliers and service providers not subject to the risk of mafia pollution is expected to be set up in each Prefecture. After the main experiments in fact, the so-called ““White List”s Special Law no. 6/2014” of suppliers and service providers not subject to the risk of mafia pollution were set-up in the Prefecture of Naples.

2.1. The National Institution of the “White List”: Law n° 190 of 6 November 2012

Although the “White List”s had been considered as an emergency solution for particularly sensitive local situations, the Legislator quickly expressed the need for implementation at national level. With the enactment of the Anti-Corruption Law (L. 190/2012), finally “White List”s have been established in each Italian Prefecture.

In particular, two important innovations are introduced: the first is constituted by the fact that the “White List”s are established for the effectiveness of anti-mafia controls exclusively for companies operating in the sectors at risk of mafia infiltration; the second novelty instead provides, through the provisions contained in the Anti-Corruption Law, that companies that intend to request registration must meet the requirements for the anti-mafia information necessary for the exercise of the related activity with an exemplary effect of the checks themselves. The Prime Ministerial Decree of 18 April 2013 in fact expressly provides that registration is voluntary: the Prefectures provide for registration within 90 days of receiving the applications; companies must only indicate the sector of activity for which they want to register and their email address and attach the necessary documentation; In Article 53 of the Anti-Corruption Law, and based on the amendments to Article 4-bis, paragraph 2, Law 40/2020, the following activities are defined as those most exposed to the risk of mafia infiltration:

extraction, supply and transport of land and inert materials;

packaging, supply and transport of concrete and bitumen;

cold rental of machinery;

supply of wrought iron;

hot freight;

autotransporter on behalf of third parties;

construction site guardian;

funeral and cemetery services;

catering, canteen management and catering;

environmental services, including collection, national and cross-border transport activities, including on behalf of third parties, waste treatment and disposal, as well as remediation and reclamation activities and other services related to waste management;

extraction, supply and transport of land and inert materials;

packaging, supply and transport of concrete and bitumen.

With the “Liquidity Decree” on 4 June 2020, the Senate, with the opinion of the Ecomafie commission, confirmed the amendment concerning a system of so-called ““White List”—Verdi”. It has been provided that all the companies that deal with “environmental services” will have to register in the ad hoc lists to participate in public procurement. Until now, the environmental activities included in the “White List”s were the activities around the management of plants and landfills and those that deal with remediation, and for the waste sector only for waste transport and disposal companies on behalf of third parties. Now, with the new amendment alongside Article 53 of the Anti-Corruption Law, all companies whose activities fall under ATECO codes 38 and 39 (waste collection, treatment and disposal, material recovery and remediation activities and other services) must register. This introduces an instrument to counter the ecomafia.

2.2. Administrative Simplification in Terms of Compulsory Registration

The real turning point occurs when the legislator, with Article 29 of Legislative Decree 90/2014, introduces the compulsory acquisition of communication and anti-mafia information regarding the release of companies operating in the sectors at risk of mafia infiltration, as identified by paragraph 53 of the Anti-Corruption Law, through the “White List”s. In particular, public administrations and entities, also constituted in single contracting stations, entities and companies supervised by the State or by another public body, and companies or enterprises in any case controlled by the State or by another public institution, as well as concessionaires of works or public services, are obliged to consult the lists of companies registered and requesting registration in the “White List”s on the institutional website of the competent Prefecture, in order to proceed the award of contracts. Until now, the provisions dictated by the law did not provide for any mandatory use of the lists either for anti-mafia checks or for the award of the related contracts. In fact, the Prime Ministerial Decree of 24 November 2016 provided that, for the subjects referred to in art. 83, there is an obligation to check in advance whether the company awarded the contract is registered in the “White List” of the relevant Prefecture, regardless of the value of the contract to be stipulated. In this way, an administrative simplification of the checks was made: the mandatory consultation of the “White List” creates an advantage in terms of controls thanks to the prior receipt of anti-mafia documentation. It also introduces the possibility for undertakings that have obtained registration for a given activity to be able to extend the registration-control effect to other economic activities other than those for which it was arranged. Consulting the lists at the Prefectures is not the only way to access the anti-mafia release certificates necessary for the award of contracts. It should be remembered that the Anti-Mafia Code had already been established in 2011 in the single national database for anti-mafia documentation (BDNA), which became active from 7 January 2016. The aim was to centralize in a single source the anti-mafia communications and information that contracting authorities and other operators must acquire, to protect the processing of sensitive data, before approving or authorising public contracts and subcontracts. The release of the documentation to the applicant takes place immediately and electronically. The BDNA has not yet entered full capacity, but it certainly represents an important tool which could, over time, allow the abandonment of the “White List” to operate an additional administrative simplification. This tool would allow time optimisation and an opportunity to avoid the unnecessary duplication of documentation. In conclusion, we can affirm that, although the registration in the “White List” remains an optional preventive transparency tool, its obligation arises and becomes a necessity when companies intend to sign contracts in the sectors considered at risk of mafia infiltration with the public administrations. The context in which the “White Lists” have become the most used tool is precisely that of public procurement.

2.3. Public Procurement

The “White List” system encourages private companies to work in the public sector if they are “censored” and, for this reason, we are concerned with the prevention of both administrative and public corruption. Regarding this, the former President of the National Anti-Corruption Authority, Raffaele Cantone, stated that the fight against (public) corruption moves on three different levels: the identification of specific risks in the individual administrations (or in particular sectors within it) and the adoption of anti-corruption plans capable of eliminating them or, at least, reducing them as much as possible; the implementation of the transparency of the procedures, so as to make the commission of offences more complicated; the sterilisation of conflicts of interest, which could undermine the impartiality of those called to take certain decisions or measures. This aspect, combined with the list tool, is embodied in the discipline of public procurement. The Public Contracts Code defines the public work contract as a contract between one or more contracting stations and one or more economic operators (i.e., companies in their broadest generality) having as its object:

- 1.

the execution of related works to one of the activities referred to in Annex I of Legislative Decree 50/2016 (construction, demolition, recovery, restructuring, restoration, maintenance, works);

- 2.

the execution or the executive planning and execution of a work;

- 3.

the realisation, by any means, of a work corresponding to the requirements specified by the contracting authority or the contracting entity which exercises a decisive influence on the type or design of the work.

When Public administrations (so-called Contracting authority) need to carry out public works or to acquire goods, services, or supplies, they cannot propose a contract to a particular company but it is necessary to follow a very specific procedure. The general principles on which the public sector is founded lie in transparency, the principles of good administration and due process, and the principle of impartiality. The administration, in line with its principles, launches a “public tender”, so defined because it is aimed at an indefinite number of potential companies which, based on the tender, offer their goods or services at a certain price. The company that respects the needs of the administration, even in terms of the most economically advantageous offer, wins the tender: only now can the relative contract be stipulated. As we learned, the contracting authorities are obliged to consult the “White List” in the Prefectures to proceed with the award of the related procurement contracts. We have come to the positive conclusion that the obligation takes place for the company that intends to participate in the tender. There have been many resolutions by ANAC, the National Anti-Corruption Association, to underline this necessity. Recently, the Authority specified that the inclusion in the “White List” is a real subjective requirement for the company that intends to participate in the tender: the lack determines the inability to contract with the public administration. As already mentioned, this is a way to balance interests between obligation to consult the “White List” and the obligation to register for the companies participating in tenders.