1. Introduction

The telecommunications sector is facing growing challenges due to the rapid expansion of mobile networks, the Internet of Things (IoT), and increasing data traffic. Maintaining quality of service, ensuring network security, and optimizing operational efficiency are crucial objectives for telecommunications companies. Identifying and mitigating anomalies in the network has become a critical aspect of achieving these objectives. While some anomalies may be harmless, such as temporary spikes in usage, others can lead to serious issues like service disruptions or network failures. Therefore, early detection of anomalies is pivotal to preventing a decline in performance and reliability.

Anomaly Detection (AD) is a key technique used in this context to identify unusual patterns that could signal problems in the network. AD refers to the process of detecting data points, entities, or events that significantly deviate from what is expected. These deviations, or anomalies, can indicate significant underlying issues such as fraud, errors, or other unusual occurrences. The process plays a crucial role in data analysis and machine learning, helping uncover instances that are different from typical patterns.

In general, defining what constitutes an anomaly is challenging. In data science, we do not have an explicit definition of normalcy, which means anomalies are often defined as rare events. This approach assumes that the majority of data is normal and that anomalies are infrequent, which can lead to complications, such as assuming all rare events are problematic. In practice, AD is an unsupervised problem since we lack a clear definition of what constitutes an anomaly. Nonetheless, anomalies can provide actionable insights across various fields, such as fraud detection in finance, where unusual transactions may indicate fraudulent activity [

1], or cybersecurity, where anomalous network traffic patterns may signal malicious intrusions [

2]. In time series data, AD plays a particularly important role. It focuses on detecting abnormal patterns over time, either in a single variable (univariate time series) or in multiple variables simultaneously (multivariate time series). In multivariate settings, joint anomalies may only become apparent through interactions between different variables. Time series AD is vital for applications like health monitoring, where unusual patterns in medical data can signal health issues [

3], and industrial fault detection, where anomalies in manufacturing processes can indicate faults or breakdowns [

4]. The data generated within telecommunications networks exhibit unique characteristics that distinguish them from other types of data. Understanding these characteristics is essential for effectively analyzing and managing network data, particularly for tasks such as AD, traffic management, and performance optimization. Network data is typically structured as time series data, where data points are collected and ordered sequentially over time. This type of data represents the variation of a specific metric as a function of time [

5]. Network data is collected at defined intervals, such as every 5 min, 15 min, or one hour, based on the requirements and capabilities of the monitoring systems [

6]. Furthermore, network usage often follows daily cycles, with peaks and troughs corresponding to human activity. For example, internet traffic might peak during the evening when people are home and online, and dip during early morning hours. This is why some metrics can exhibit seasonality, so understanding and analyzing these seasonal patterns are essential for effective AD [

7]. Also, some metrics are highly correlated, meaning that they increase or decrease together. For example, network traffic and latency might be positively correlated; as traffic increases, latency often increases too [

8]. Finally, network data is contextual, which means that raw data is accompanied by some additional information and metadata that provide some context, enhancing its meaning and usability especially for AD. For instance, anomalies at night might be normal values during the day, so contextual network data provides valuable insights that go beyond what raw data can offer, enabling more effective network management and optimization [

9].

Since network data has these characteristics, some issues could arise in the AD process. For example, seasonal data can lead to false positive detected cases, where normal seasonal variations might be flagged as anomalies, and conversely, to false negative cases where actual anomalies might be overlooked due to masking by seasonal patterns [

10]. Moreover, correlation in network data presents some challenges, as it can mask critical patterns and lead to misleading conclusions in AD systems. When features are highly correlated, it can result in overfitting, where the model becomes too tailored to the training data, reducing its generalization to unseen data. Properly handling correlated features is crucial for building robust predictive models, accurate AD systems, and effective network management strategies. By using appropriate techniques to manage correlation, organizations can improve their analytical capabilities and make more informed decisions, leading to better network performance and reliability [

11]. Recent research has shown a growing interest in using Mahalanobis-based methods for detecting anomalies in modern 5G networks. These approaches have been applied to log anomaly detection [

12], KPI time-series classification [

13], and streaming data analysis [

14], with new work also extending the method to handle non-Gaussian data [

15]. Together, these studies highlight how Mahalanobis Distance remains a practical and effective tool for identifying multivariate anomalies in telecommunications networks.

The problem addressed in this article centers on improving AD in the telecommunications domain, particularly in time series data representing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). The challenges of dealing with false positives and false negatives are especially relevant, as incorrect detection can lead to unnecessary investigations, wasted resources, and potentially compromised performance. Conversely, missed anomalies can have serious consequences, resulting in network failures or security breaches. This article discusses strategies for addressing these challenges, focusing on both proactive and reactive measures, and introduces an advanced method for AD aimed at reducing false positives and false negatives while maintaining network reliability and optimizing operational efficiency. The composition of this paper is as follows. We begin with a review of related work in

Section 2, summarizing key approaches and techniques relevant to AD in telecommunications. In

Section 3, we describe the materials and methods used in this study, focusing on the application of Mahalanobis Distance (MD) in networks. This section includes a description of the network data, the preprocessing steps, and the mathematical formulation of the MD, along with SHAP values for interpretability. We conclude the section by outlining the model workflow and explaining how results are aggregated from the lowest to the highest network level. In

Section 4, we present and analyze the results of our model, beginning with a review of initial experiments and leading into a benchmark comparison with baseline AD methods: Isolation Forest (IF), Local Outlier Factor (LOF) and One-Class Support Vector Machines (SVM). Several use-case examples are also provided. Finally, in

Section 5, we conclude the paper and discuss potential future perspectives.

Introduction of an Unsupervised MD Framework: We propose a scalable AD methodology that leverages MD to analyze multivariate relationships in KPIs without requiring labeled datasets.

Effective Hierarchical Aggregation Strategy: We introduce a novel approach that aggregates anomaly scores at different network levels (cells, sectors, and sites) to localize and prioritize issues effectively, enabling actionable insights for telecom operators.

Incorporation of Data Preprocessing Techniques: The methodology adjusts KPI ratios by accounting for contextual factors like sample size and normalizing feature distributions, improving detection accuracy while maintaining proportionality between metrics.

Dimensionality Reduction for Performance Optimization: We implement a systematic feature selection process that identifies the most relevant KPIs, balancing model efficiency and accuracy while maintaining broad anomaly coverage.

Comprehensive Comparative Analysis: We benchmark the MD-based approach against IF, LOF and One-Class SVM, demonstrating superior computational efficiency and competitive detection accuracy, particularly for large-scale datasets.

Cross-Dataset Validation: We validate the generalization capability of the MD approach across datasets from different time periods (summer, winter, spring), demonstrating that the correlation structure of KPIs remains stable across seasonal variations.

Practical Use Case Demonstration: Real-world examples illustrate the model’s ability to detect critical anomalies, such as decreases in the RACH success rate, and guide operators in addressing network performance issues effectively.

2. Related Work

AD in network traffic has been the focus of extensive research, with various techniques developed to address the unique challenges of telecommunications environments [

16]. These methods can be broadly categorized based on their learning paradigm and underlying algorithmic approach.

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of the main AD families, highlighting their key characteristics and applicability to network monitoring.

Given the scarcity of labeled anomaly data in operational telecommunications networks, this study focuses on unsupervised methods. Within this category, three techniques have emerged as widely adopted baselines: IF, which isolates anomalies through efficient tree-based partitioning and has demonstrated scalability in production systems [

29]; LOF, which detects outliers by measuring local density deviations; and One-Class SVM, which learns a decision boundary around normal data in high-dimensional spaces [

30].

However, these methods face challenges when applied to telecommunications KPI data, which exhibits high dimensionality, strong feature correlations, and multivariate dependencies. MD addresses these limitations by explicitly modeling the covariance structure of normal data, providing a statistically principled measure of deviation that accounts for inter-feature relationships. Unlike distance-based methods that treat features independently or density-based approaches that may struggle with varying-density regions, MD leverages the full covariance matrix to assess how unusual a data point is relative to the expected multivariate distribution.

To validate the effectiveness of the MD-based approach, we benchmark it against IF, LOF, and One-Class SVM—the current state-of-the-art in unsupervised network anomaly detection. This comparative analysis evaluates detection accuracy, computational efficiency, and practical applicability in the context of large-scale telecommunications monitoring.

3. Material and Method

3.1. Overall Process

The general workflow of our AD model is illustrated in

Figure 1. The process consists of two key phases: the training phase and the prediction phase.

In the training phase, the model begins by loading historical network data, followed by preprocessing steps to clean and prepare the data. This includes handling missing values, and building some features. Then a method for removing irrelevant or noisy features is applied to improve accuracy. Finally, final parameters such as the mean, covariance matrix, relevant features, and the distance distribution are calculated and saved. These parameters are essential for detecting anomalies in the subsequent prediction phase.

In the prediction phase, new data is loaded and preprocessed using the same steps applied during training to ensure consistency. The model then retains only the relevant features, as determined during the training phase, and computes the MD for each data point. This distance measures how far each point deviates from the distribution of normal data. Based on the computed distance, each data point is classified into different risk levels (high, medium, or low), helping to assess whether it represents an anomaly. For data points identified as anomalies, we compute the top contributing factors, offering insights into the causes of the detected anomalies. Results are aggregated from the lowest network element level to the highest, enabling a hierarchical approach to identifying and addressing network issues.

3.2. Loading Data

The data is structured at two granular levels: element IDs and datetime keys. An element ID represents a specific network component, such as a cell or sector, while a datetime key corresponds to a defined timestamp, typically representing 15-min intervals.

3.2.1. Training Phase

During the training phase, the model loads historical data over a specified range of datetime keys. This data can include all element IDs or a selected subset based on operational requirements. For each element ID, the data contains KPIs recorded at each datetime key, enabling the model to capture temporal patterns and spatial relationships across network components.

3.2.2. Prediction Phase

In the prediction phase, which operates in real time, the model processes batches of element IDs corresponding to each incoming datetime key. For each element ID, the model calculates an anomaly score using the MD, assigns a score classification (low, medium, or high risk), and identifies the top contributing factors for instances classified as high-risk anomalies.

3.3. Preprocessing

Preprocessing is a crucial step in preparing data for analysis, modeling, and AD. The preprocessing method presented in this work applies specific adjustments to the rate metrics to align with business requirements.

The method is inspired by the rule of succession, a principle in probability theory that estimates the likelihood of an event occurring, particularly when dealing with small sample sizes or when an event has not been observed. This principle provides a framework for handling cases with limited or no prior data [

31].

The preprocessing approach updates metrics representing KPIs, such as success rates and drop rates. The success rate is defined as the ratio of successes to the total number of attempts, while the drop rate is defined as the ratio of failures to the total number of attempts.

Technically, the process begins by converting the success rate into a drop rate, where the number of failures is calculated as the total number of attempts minus the number of successes. A constant is then added to the denominator (number of attempts), and a constant is subtracted from the numerator (number of failures). This adjustment enables the model to distinguish between, for example, a drop call rate based on 5 calls and a drop call rate based on 50 calls. As a result, the model interprets drop rate values differently depending on the number of attempts, ensuring the AD process accounts for varying sample sizes.

The constants used for these adjustments are learned from the model by analyzing the distribution of the number of failures and attempts for each KPI.

3.4. Feature Selection by Noise Reduction

This method focuses on identifying and removing noisy features that may mislead the model during AD.

The process begins with a sample of raw data labeled by subject matter experts (SMEs). Each row is annotated to indicate whether it represents an anomaly. The model generates an anomaly score for each row, and by comparing these scores to the labels, it computes a performance metric: the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUC-ROC) curve.

The AUC-ROC curve is a graphical representation of the diagnostic ability of a binary classifier. It is generated by plotting the True Positive Rate (TPR), defined as the ratio of correctly predicted positive instances to the actual positives, against the False Positive Rate (FPR), defined as the ratio of incorrectly predicted positive instances to the actual negatives, across various threshold settings [

32]. The AUC value represents the probability that the classifier will rank a randomly chosen positive instance higher than a randomly chosen negative instance. For instance, an AUC of

indicates an

likelihood of correct ranking between a positive and negative instance.

Once the original AUC value is computed using all features, the method iteratively evaluates the impact of each feature. In each iteration, one feature is removed, and the AUC value is recalculated without that feature. If the new AUC value exceeds the original AUC value, the removed feature is considered noisy. By iterating over all features, the process identifies both the relevant and noisy features, ensuring that only the most informative features are retained in the model.

3.5. Mahalanobis Distance

The MD is a context-aware metric that measures how far a data point deviates from the mean of a distribution, accounting for correlations among variables and differences in variable scales. Unlike the Euclidean distance, which treats each feature independently, MD provides a multivariate perspective by considering the relationships between variables [

32].

MD extends the concept of standard deviations in a univariate distribution to multiple dimensions. The distance is zero when a point

P coincides with the mean of the distribution

D and increases as

P deviates from the mean along principal component axes [

33]. The MD between a point

x and the mean

of a distribution with covariance matrix

S is defined as:

where:

x is the observation vector,

is the mean vector of the distribution,

S is the covariance matrix of the distribution,

T denotes the transpose of the vector,

is the inverse of the covariance matrix.

A higher MD value indicates that a data point is more dissimilar from the mean, accounting for variable correlations, and may suggest a potential anomaly.

While MD effectively identifies outliers in multivariate data, its aggregated nature limits its ability to reveal individual feature contributions to the overall distance. To address this limitation, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values are proposed for computing the contribution of each feature, offering more detailed insights into AD (next section).

3.6. SHAP Values

SHAP values provide a consistent and interpretable measure of feature importance, derived from cooperative game theory [

34]. Unlike traditional methods that yield a single aggregated score, SHAP values offer detailed insights into the contribution of each feature to specific predictions, facilitating the diagnosis and understanding of anomalies in the data.

More specifically, SHAP values are based on the Shapley value from cooperative game theory and are used to explain the outputs of machine learning models. They quantify the contribution of each feature to a model’s prediction by evaluating all possible combinations of features. The SHAP value for a given feature represents its average marginal contribution across these combinations, ensuring a fair and consistent attribution of the prediction to individual features.

This approach enables both:

By offering these levels of interpretability, SHAP values make complex models more understandable and their predictions more transparent [

34].

3.7. Anomaly Detection Workflow

The AD workflow consists of two phases: training and prediction.

3.7.1. Training Phase

The training phase utilizes a dataset comprising one month of data with 165 element IDs, where metrics are recorded at 15-min intervals. The features representing KPIs undergo preprocessing steps, including filling missing values and categorizing KPIs into three groups: success KPIs, drop KPIs, and normal KPIs. Success KPIs are converted into drop KPIs, and both success and drop KPIs are adjusted to meet business requirements, as described in

Section 3.3. Normal KPIs remain unchanged.

Using a labeled sample consisting of three days of data and 20 element IDs, the workflow identifies relevant features by applying the feature selection method outlined in

Section 3.4. After filtering the data to retain only relevant features, the MD is computed for each row in the training set. The following parameters are saved for use during the prediction phase:

List of relevant features,

Mean vector of the features,

Covariance matrix of the features,

Distribution of the MD values.

3.7.2. Prediction Phase

During the prediction phase, incoming data undergoes the same preprocessing steps as in the training phase. The data is then restricted to the relevant features identified during training. The MD is computed for each data point, serving as the anomaly score. Based on the saved MD distribution, the anomaly score is categorized as low, medium, or high using predefined quantile thresholds. Data points with high anomaly scores are flagged as potential anomalies.

For each flagged anomaly, SHAP values are computed to determine the contribution of each feature to the anomaly. By focusing the SHAP value calculation solely on high anomaly scores, the workflow enhances computational efficiency, as SHAP value computation can be resource-intensive.

This workflow combines a distance-based AD technique with labeled data to improve accuracy and interpretability. It is designed to efficiently identify anomalies while providing insights into their root causes.

3.8. Aggregation

The model computes anomaly scores per cell and datetime across multiple KPIs simultaneously. When an anomaly is detected, a SHAP analysis determines the KPI contributing most significantly to the anomaly.

These anomaly scores are aggregated at different levels using a straightforward averaging procedure, enabling insights across various network layers. The aggregation hierarchy follows the structure: Cell → Site → Time. For instance, to compare the level of anomalies across all sites at a given time, the MD scores are first averaged by cell and then by site.

This hierarchical aggregation provides tailored insights depending on the use case. By maintaining this structure, the procedure effectively narrows down relevant insights at each level, aiding network troubleshooting and analysis. Further details on how these aggregated scores are applied are provided in

Section 4.8.

4. Results and Discussions

This section presents the results of our study, which includes a description of the dataset and the outcomes of multiple experiments designed to evaluate the performance of the proposed AD approach. The experiments aim to:

Evaluate the impact of different data representations on AD performance.

Assess the effect of incorporating KPI denominators (e.g., number of attempts) as features.

Investigate the benefits of applying smoothing adjustments to KPI ratios.

Compare detection accuracy and computational efficiency against baseline unsupervised methods (IF, LOF, One-Class SVM).

Demonstrate practical applicability through real-world network use cases.

4.1. Data Description

The dataset used in this study consists of time series data collected from a telecommunications network, capturing network performance metrics at 15-min intervals. Each record corresponds to a specific network element, identified by a unique element ID, and includes several KPIs relevant to network monitoring and AD.

The dataset’s primary fields are:

Element ID: Uniquely identifies each network element.

Datetime Key: Represents the specific 15-min interval during which the KPIs were recorded.

KPI Values: Reflect the performance of the element at the given time.

Additionally, the dataset provides contextual information about each element, including its corresponding sector and site, allowing for granular analyses. Elements can be grouped by sector or site to gain insights into localized network performance.

Example KPIs include:

Success Rate KPIs: Metrics such as connection and establishment success rates.

Drop KPIs: Metrics such as session drops and packet losses.

Throughput KPIs: Metrics for both downlink and uplink performance.

Each success and drop KPI is calculated as a ratio of successes or drops (numerator) to the number of attempts (denominator). This structure supports comprehensive, time-based evaluations of network behavior, aiding in AD and optimization tasks.

4.2. Evaluating the Impact of Data Representations on Mahalanobis Distance Performance for Anomaly Detection

The primary objective of this section is to explore the influence of different data representations on the performance of MD for AD. Although the MD is theoretically optimal under the assumption of multivariate normality, strict normality is not required for it to perform effectively in practice. MD has been shown to remain robust in detecting anomalies even when data deviate from Gaussianity, provided that the covariance structure captures meaningful relationships between features [

33,

35,

36]. In this study, the KPIs are based on counters and ratios, which may not strictly follow normal distributions but exhibit stable statistical behavior across time and cells. This makes MD a suitable and reliable approach for identifying multivariate deviations in telecom networks without relying on strong parametric assumptions. Since MD is sensitive to the distribution and relationships between features, variations in how data is represented can significantly impact its effectiveness in detecting anomalies. The experiments in this section evaluate the model’s performance across different representations and identify the most effective approach.

4.2.1. Experiment 1: Exploring Data Representations

In the first experiment, we apply MD to a training dataset comprising one month of data, including around 3000 element IDs. Three distinct data representations are tested:

Method 1: Using raw KPI values at a specific time t.

Method 2: Combining the KPI values at time t with values 24 h earlier ().

Method 3: Using residuals obtained after seasonal decomposition of KPI values.

Experimental Setup

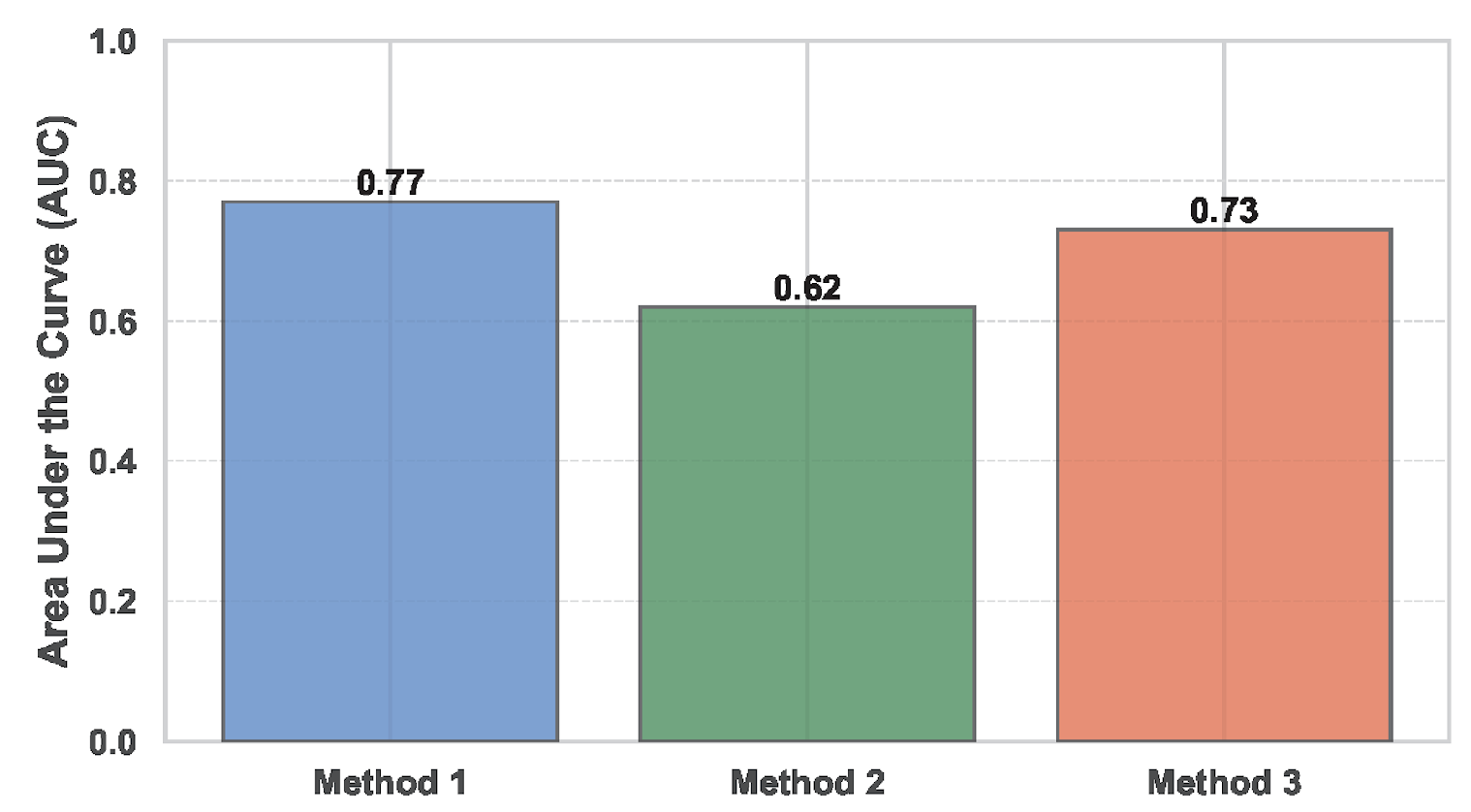

We evaluate these methods using a labeled dataset containing three days of data and 20 element IDs. We assess the model’s performance with AUC, which measures its ability to distinguish between normal and anomalous data points.

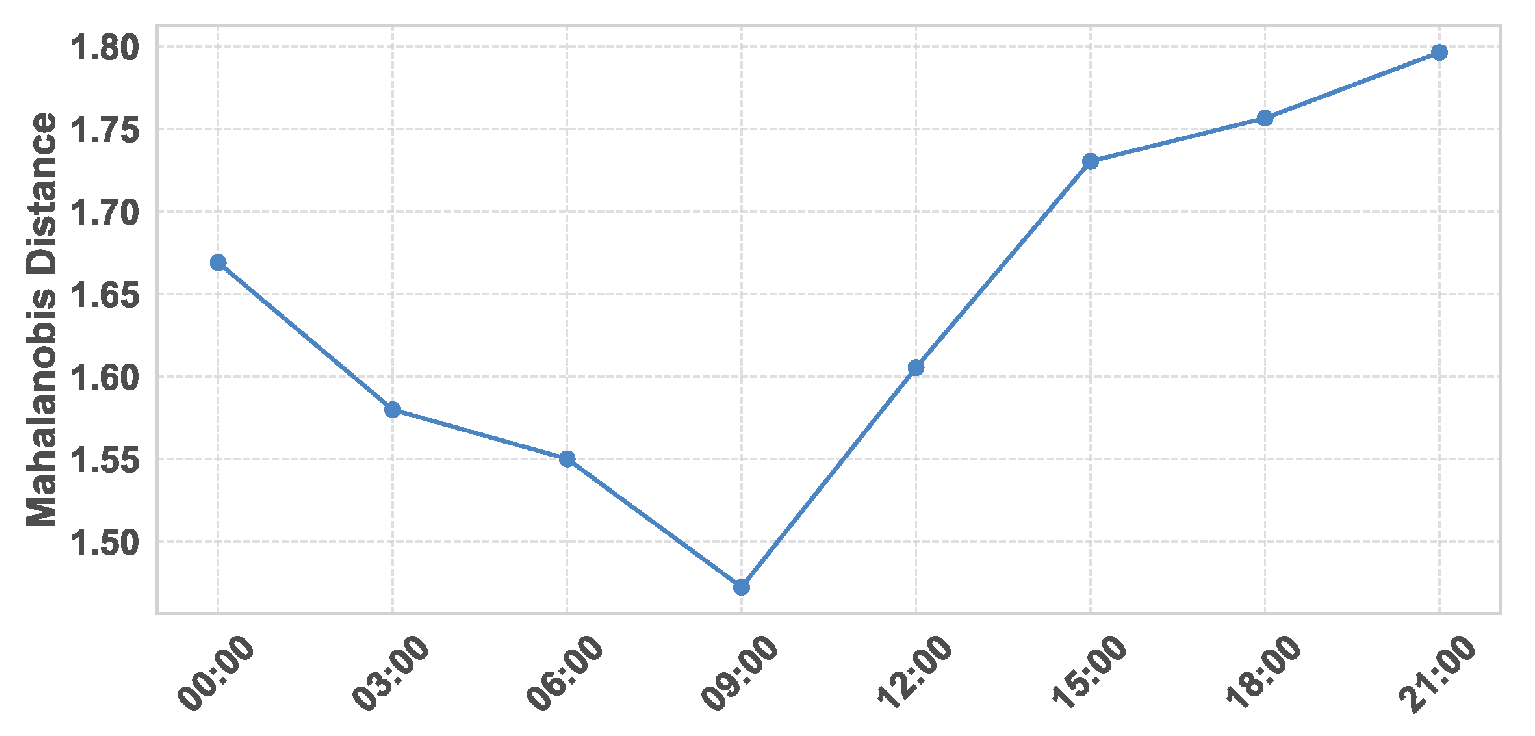

Figure 2 summarizes the results for each method.

Results and Observations

Method 1 (Raw KPI values): This approach achieves the highest AUC of 0.77. The raw data representation captures the intrinsic relationships between features without introducing additional complexity, making it effective for AD.

Method 2 (Including KPI values from ): Adding temporal dependencies reduces the AUC to 0.62. The additional features likely introduce noise and redundancy, diminishing the model’s ability to detect anomalies effectively.

Method 3 (Residuals from seasonal decomposition): This method yields an AUC of 0.73. While removing seasonal patterns helps the model focus on abnormal variations, some useful information may be lost during decomposition.

In summary, Method 1 performs best, demonstrating that raw KPI values provide sufficient information for effective AD in this dataset.

4.2.2. Experiment 2: Incorporating KPI Denominators

In this experiment, we hypothesize that adding the denominator of KPIs (i.e., the number of attempts) as a feature can improve performance by providing additional context for interpreting KPI ratios.

Experimental Setup

We use the same dataset and three methods from Experiment 1, including the denominator values as additional features. We measure the impact on AUC and present the results in

Table 2.

Results and Observations

Method 1 (Raw KPI values): AUC improves from 0.77 to 0.86. The additional denominator information helps the model differentiate between similar KPI ratios derived from different sample sizes, enhancing AD accuracy.

Method 2 (Including KPI values from ): AUC increases from 0.62 to 0.69, but this method still underperforms compared to others due to the noise introduced by temporal dependencies.

Method 3 (Residuals from seasonal decomposition): AUC rises from 0.73 to 0.80, indicating that the denominators provide valuable context even when seasonal components are removed.

The results confirm that adding KPI denominators significantly enhances performance across all methods, with

Method 1 maintaining its superiority (

Table 2). Moving forward, we focus on optimizing Method 1.

4.2.3. Experiment 3: Adjusting KPI Ratios

Building on the previous experiments, we explore the impact of regularizing KPI ratios by adding a fixed constant to the denominator. This adjustment aims to reduce sensitivity to small denominators, which can disproportionately amplify anomalies.

where:

n is the numerator (e.g., successes or failures),

d is the denominator (e.g., total attempts),

c is the fixed constant added to the denominator.

Experimental Setup

Three variations of Method 1 are tested:

Raw KPI ratios without adjustments (from Experiment 2).

KPI ratios adjusted by adding a fixed constant to the denominator.

KPI ratios adjusted by adding a fixed constant to the denominator and including denominators as features.

The constant is chosen based on statistical analysis of the training data, guided by domain expertise. The AUC values for each approach are presented in

Table 3.

Results and Observations

Adjusted KPI ratios: Adding a constant to the denominator slightly increases AUC to 0.88. While this adjustment mitigates the impact of small denominators, it may introduce minor distortions in other cases.

Adjusted KPI ratios with denominators: Combining adjustments with denominator inclusion yields the highest AUC of 0.93, demonstrating the complementary benefits of these modifications.

4.2.4. Experiment 4: Optimizing KPI Adjustments

In this experiment, we test three variations of the adjustment methods to refine the KPI representations further by using a dataset of one month of data and 165 element IDs and using denominators as features.

Experimental Setup

We evaluate three approaches inspired by the rule of succession, which provides a theoretical foundation for smoothing ratio estimates [

37]. While the classical Laplace rule adds a fixed constant (typically +1) to both numerator and denominator, telecommunications KPIs exhibit vastly different scales—ranging from tens to millions of attempts per time period. A fixed constant would be ineffective for such heterogeneous data. Therefore, we adapt the theoretical framework by deriving constants empirically from the operational data distribution, ensuring that smoothing adjustments are proportional to the actual scale of each KPI.

Adding a constant to the denominator: The denominator constant is computed as follows: (1) for each time window, aggregate the total attempts across all network elements; (2) divide by the number of unique elements to obtain the average attempts per element; (3) average these values across all time windows. This data-driven constant represents the typical attempt volume and prevents extreme ratio fluctuations caused by small denominators. For example, if the mean attempt volume is 10,000, adding this constant ensures that a cell with only 10 attempts is smoothed appropriately, whereas a fixed +1 would have negligible effect.

Subtracting a constant from the numerator: For success KPIs, we first convert them to failure format by computing (failures), while drop KPIs retain their original numerator n. The numerator constant is determined through the following procedure: (1) aggregate failure counts per time window and calculate the mean across all windows for each KPI; (2) identify the KPI with the lowest mean as the reference; (3) for the reference KPI, analyze the 99th quantile of its distribution and map it to a baseline constant based on its range (e.g., if the 99th quantile falls between 1 and 2 in a 0–10 range, the reference constant is set to 2); (4) for other KPIs, scale the constant proportionally: ; (5) apply a log10 transformation to prevent extreme constant values while maintaining proportionality across KPIs. This approach ensures that the constant removed from each KPI is appropriate to its operational baseline, effectively reducing noise from low-level failures.

Combining adjustments to both numerator and denominator: This method applies both the denominator and numerator adjustments simultaneously, using the data-driven constants derived above. The goal is to evaluate whether combined smoothing provides additional benefits over individual adjustments.

Results and Observations

Adding a constant to the denominator: Achieves an AUC of 0.98, indicating substantial improvement in smoothing KPI variability.

Subtracting a constant from the numerator: Delivers the best performance with an AUC of 0.99, effectively reducing false positives caused by outliers.

Combining adjustments: Results in an AUC of 0.96, indicating that the combined application of both adjustments does not lead to improved efficiency.

The results are summarized in

Table 4, demonstrating the superior performance of the subtracting a constant from the numerator method.

4.2.5. Key Insights on Optimal Data Representation

Through these experiments, we gain a clearer understanding of the strategies that contribute to effective MD-based AD:

Raw KPI values (Method 1) serve as a practical starting point, capturing relationships between features without introducing additional complexity.

Including denominators provides valuable context by anchoring KPI ratios to their sample sizes. This step helps the model interpret variability more accurately, particularly when data is drawn from diverse conditions.

Regularizing KPI ratios reduces sensitivity to extreme values caused by small denominators. This adjustment works well in combination with denominator inclusion, improving the model’s reliability in detecting patterns.

Adjustments to numerator offer a more nuanced representation of the data, allowing the model to balance its focus across different types of metrics.

Incorporating seasonality, either by using larger time windows or removing seasonal components, did not show significant benefits. While these methods aim to account for temporal patterns, they introduce noise or lead to the loss of critical information, ultimately reducing the model’s ability to detect anomalies effectively.

In the next sections, we build on these findings to refine the model and compare its performance to other standard methods for unsupervised AD.

4.3. Comparative Analysis with Baseline Methods

To evaluate MD’s performance, we compare it against three widely-used unsupervised baselines: IF [

25], LOF [

24], and One-Class SVM [

26]. As discussed in

Section 2, these methods represent different detection paradigms—isolation-based, density-based, and boundary-based, respectively—making them suitable benchmarks for assessing MD’s multivariate covariance-based approach. Our goal is to evaluate their detection accuracy and computational efficiency across datasets of varying sizes.

4.3.1. Experimental Setup

We conducted the analysis using a new dataset to validate the consistency of MD’s performance metrics. The experiment focused on three types of training datasets:

Small dataset: 15 days of data.

Medium dataset: One month of data.

Large dataset: Two months of data.

The datasets included 165 element IDs, and the experiment evaluated both training and prediction phases. We worked on all 44 original features. The analysis measured the following:

Accuracy: Evaluated using AUC.

Computational efficiency: Measured as the time required for score computation during the training phase, prediction phase, and SHAP value calculation for contributor analysis.

The goal was to compare the computational performance and AD capability of MD, IF, LOF and One-Class SVM across different dataset sizes.

4.3.2. Results and Observations

Prediction Time and Accuracy on Test Data

During the prediction phase on the test set and using all features, MD demonstrated significantly faster computation times compared to all three other methods, especially for larger datasets. Additionally, MD consistently achieved higher AUC values across all dataset sizes, highlighting its superior detection capability in this context (

Table 5 and

Table 6). These findings, observed consistently across different training set sizes, indicate that the approach exhibits stable behavior with reliable detection patterns and performance relative to baseline AD methods.

4.4. Cross-Dataset Validation

To evaluate generalization across different time periods, we tested the MD approach using training sets collected during different seasons and evaluated on a common test set.

4.4.1. Experimental Setup

We trained the MD model using two training sets of one month each, collected during summer and winter periods. Both models were evaluated on the same spring test set, requiring the patterns learned from summer or winter data to transfer to a different seasonal context. The datasets included 165 element IDs and all 44 original features.

4.4.2. Results and Observations

Across both seasonal training sets, MD achieved prediction times of 1.32 s (summer) and 2.09 s (winter), with AUC values of 0.89 and 0.91, respectively (

Table 7). These results are within the range observed in the original experiments (AUC: 0.86–0.9, prediction time: 1.12–1.87 s). The method demonstrates consistent detection performance across datasets from different time periods.

We hypothesize that this result is due to MD’s reliance on covariance structure rather than absolute feature values. The multivariate relationships between KPIs remain relatively stable across different time periods, even as the absolute values of traffic volumes and individual KPI magnitudes vary. This structural stability allows the covariance-based approach to maintain consistent detection performance across seasonal datasets.

4.5. Feature Selection

This section evaluates the impact of dimensionality reduction on the performance and efficiency of the MD model. By systematically eliminating less relevant features, we aim to assess whether this approach improves AD accuracy and reduces computational overhead.

4.5.1. Experimental Setup

The analysis focuses on the MD model and considers the updated KPIs, examining the importance of doing KPI adjustments and the effect of feature reduction on execution time and AUC. Starting with all features, individual features are iteratively removed. At each step, the remaining features are evaluated, and the corresponding AUC, execution time, and number of features are recorded. This allows us to track changes in model performance and efficiency as noisy or redundant features are filtered out.

4.5.2. Results and Observations

Table 8 summarizes the changes in AUC and execution time as features are progressively removed. The process begins with 30 updated features, where initial AUC and execution time are noted. As feature reduction progresses, the number of features decreases, and the model’s performance and efficiency are recalculated.

The results highlight the benefits of feature reduction in improving AUC and reducing execution time across different training sizes. Initial filtering steps yield noticeable improvements in AUC, particularly when transitioning from 30 to the following number of features. However, further reduction in the number of features beyond this point leads to diminishing returns, suggesting that most noisy or redundant features are removed early in the process.

From a computational perspective, feature reduction reduces execution time significantly, especially for larger datasets. This demonstrates the potential of this approach to balance accuracy and efficiency, making it suitable for various training sizes and complexities.

It is worth noting, however, that the removal of certain features may limit the model’s ability to detect anomalies associated with those features. This creates a trade-off between improved performance and efficiency on one hand, and the ability to detect a broader range of anomalies on the other. Additionally, since this procedure is supervised, the removed features are selected based on past anomalies, which may introduce bias towards detecting previously observed anomalies. It is also important to note that the decision to remove features is optional, allowing users the flexibility to retain specific features if necessary.

4.6. Key Insights

Through a series of experiments, we derive the following key insights regarding the use of MD and baseline methods for AD in network performance data:

Performance Comparison: For the telecommunications KPI anomaly detection task evaluated in this study, MD consistently outperforms baseline methods, achieving higher AUC values across various training dataset sizes. This demonstrates the effectiveness of MD in capturing anomalies in scenarios where multivariate relationships among features are critical, such as correlated network performance metrics.

Computational Efficiency: MD exhibits significantly faster prediction times compared to baseline AD methods, with the performance gap becoming more pronounced as the training dataset size increases. The matrix-based computation of MD scales more efficiently than the tree-based structure of IF, the density-based computations required by LOF, and the boundary-optimization process used by One-Class SVM. This computational advantage is particularly important in network AD contexts, where models must process high-dimensional KPI data across thousands of network elements in near real time to enable timely operational responses.

Impact of Feature Selection: The dimensionality reduction process improves both the detection accuracy and computational speed of MD by eliminating noisy features. However, this comes with a trade-off: the model’s ability to detect anomalies is limited to the retained features, meaning anomalies that manifest primarily in excluded KPIs will go undetected.

Role of Denominators and Cross-Dataset Generalization: Incorporating denominators (e.g., the number of attempts) into KPI calculations enhances the accuracy of MD by providing essential context. This approach mitigates the influence of small denominators, which can otherwise exaggerate anomalies. Furthermore, MD demonstrates consistent detection performance across datasets from different time periods, with models trained on summer or winter data maintaining comparable AUC values (0.89–0.91) when evaluated on spring data. This generalization capability suggests that the correlation structure between KPIs remains stable across seasonal variations, despite changes in absolute traffic volumes.

Aggregation and Analysis: Aggregating MD scores across temporal and spatial dimensions facilitates the identification of anomalous sites, sectors, and cells. This approach provides actionable insights by narrowing the scope for troubleshooting and linking anomalies to specific KPIs.

4.7. Discussion

While the proposed MD–based approach effectively captures multivariate deviations, it is particularly suited for detecting multivariate point anomalies, where individual observations deviate jointly across several KPIs. However, the method does not explicitly model temporal patterns, which means it may miss certain contextual or collective anomalies. For example, values that appear normal during nighttime but become abnormal during peak traffic hours, or gradual performance drifts that remain within statistical thresholds at each time step but accumulate over time. In practice, however, such contextual or collective anomalies are less frequent in telecom networks, where point anomalies are the predominant type of issues. It is also important to note that the superior performance of the raw KPI input observed in this study reflects the specific datasets used in our experiments and may not generalize to all network scenarios. In future work, hybrid methods that integrate multivariate anomaly detection with temporal modeling techniques (e.g., rolling baselines, time-aware thresholds, or temporal embeddings) could be explored to address these limitations more effectively.

4.8. Use Case Analysis

This section demonstrates the practical application of our aggregation approach to network AD. We describe the concepts of aggregations, followed by two specific use cases to illustrate how the methodology aids in identifying and analyzing network issues across different levels.

4.8.1. Aggregation Concepts

Anomaly scores are computed per cell and datetime across multiple KPIs simultaneously. When an anomaly is detected, a SHAP analysis identifies the KPI contributing most significantly to the anomaly. This approach enables anomaly score aggregation across various network levels, providing tailored insights based on the hierarchy: Cell → Site → Time.

The aggregation procedure follows these principles:

Averaging: Scores are averaged sequentially by cell, then by site, and finally by time. For example, to compare anomalies across all sites at a specific time, the MD scores are first averaged by cell and then aggregated to the site level.

Hierarchical Insights: The layered structure ensures insights are aligned with specific use cases, narrowing down anomalous behavior at the desired network level.

Use Case Alignment: This aggregation methodology adapts to diverse use cases, as demonstrated in subsequent examples, enabling AD and troubleshooting.

4.8.2. Use Case: Identifying Key Anomalies on June 29 Through KPI Analysis

Context and Intent

A network troubleshooter aims to investigate anomalies on a daily basis, focusing on time periods with the highest aggregated MD scores. The goal is to identify and analyze the specific cells and KPIs contributing to anomalous behavior for effective troubleshooting.

Procedure

- 1.

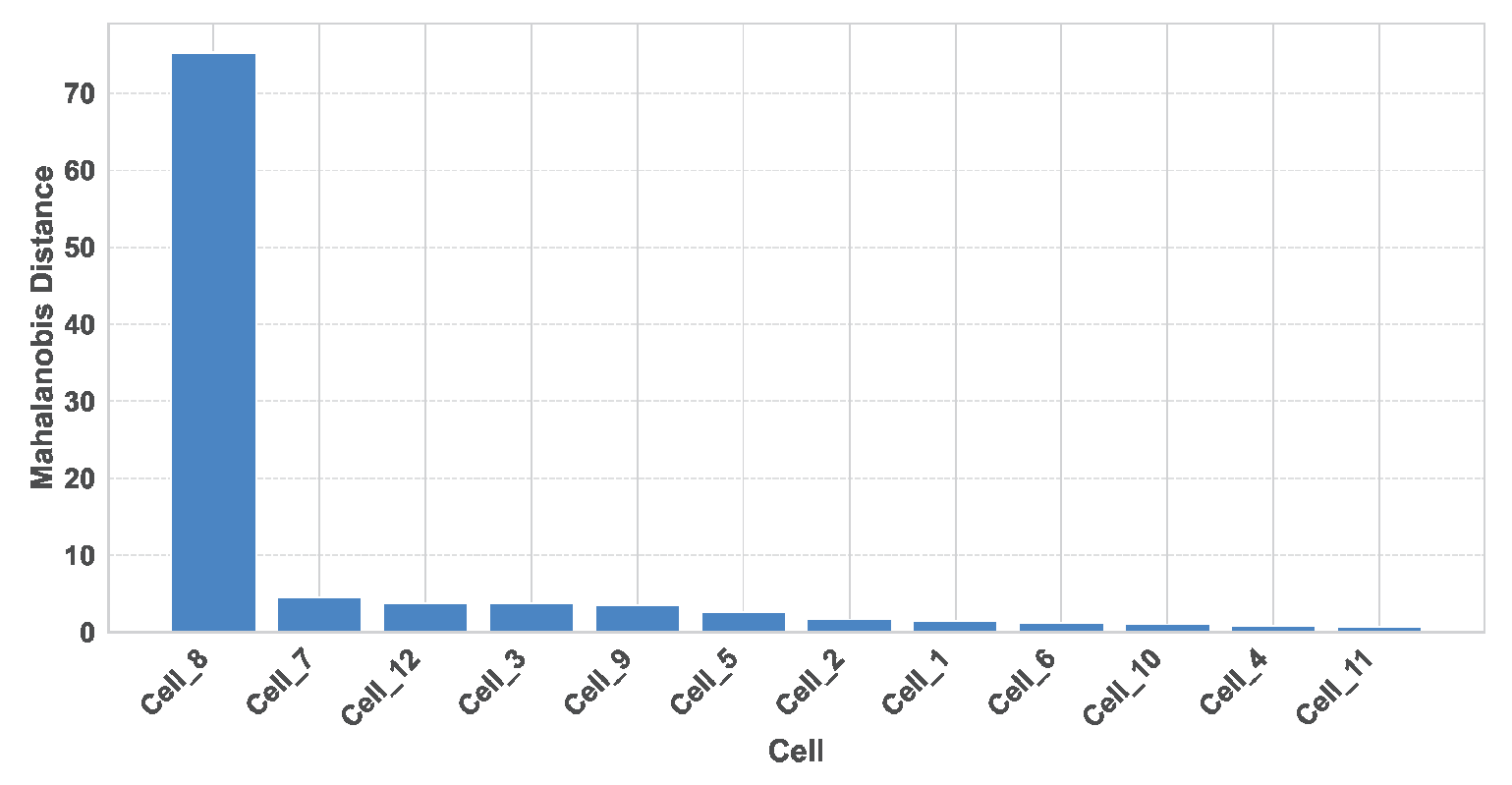

Identify the time period with the highest aggregated MD score across all sites (

Figure 3).

- 2.

Drill down to the site with the highest aggregated MD score for the identified time period (

Figure 4).

- 3.

Analyze the MD scores of individual cells within the most anomalous site to pinpoint the top-contributing cell (

Figure 5).

- 4.

Perform a KPI-level analysis of the identified cell using SHAP values to determine the main contributor to the anomaly (

Figure 6).

Figure 3.

Mean MD score aggregated by site for 29 June 2024. Each point represents the mean MD score for the corresponding 3-h bucket starting at the time indicated on the X-axis.

Figure 3.

Mean MD score aggregated by site for 29 June 2024. Each point represents the mean MD score for the corresponding 3-h bucket starting at the time indicated on the X-axis.

Figure 4.

Mean MD score aggregated by site for 29 June 2024, between 21:00 and 24:00. Each site is represented by its mean MD score.

Figure 4.

Mean MD score aggregated by site for 29 June 2024, between 21:00 and 24:00. Each site is represented by its mean MD score.

Figure 5.

MD score per cell for site Site_1 during 29 June 2024, between 21:00 and 24:00.

Figure 5.

MD score per cell for site Site_1 during 29 June 2024, between 21:00 and 24:00.

Figure 6.

Temporal variations in the RACH success rate for Cell_8 on 29 June 2024. Red highlights indicate high failure rates detected by the MD analysis.

Figure 6.

Temporal variations in the RACH success rate for Cell_8 on 29 June 2024. Red highlights indicate high failure rates detected by the MD analysis.

Results

On 29 June 2024, the aggregated results identify the period from 21:00 to 24:00 as the most anomalous interval of the day, with the highest MD scores observed across sites (

Figure 3). During this period, Site_1 exhibits the highest aggregated MD score, making it the focal point for further investigation (

Figure 4).

Within this site, cell Cell_8 stands out with the highest MD score, signaling a significant anomaly localized to this network element (

Figure 5). A subsequent SHAP analysis of this cell attributes the anomaly primarily to a degradation in the RACH success rate, as indicated by a marked increase in failures during the anomalous period (

Figure 6). (The RACH success rate (Random Access Channel success rate) is a KPI in telecom networks that measures the percentage of successful random access attempts made by user devices to establish a connection with the network).

Conclusion

The analysis highlights a significant decrease in the RACH success rate for Cell_8 during the anomalous period on 29 June 2024, as shown in

Figure 6. This decline suggests potential issues with network accessibility, aligning with the high MD scores observed.

To address such a drastic decrease, telco operators are advised to verify and adjust RACH parameters to ensure efficient access procedures. Additionally, they should assess congestion levels and consider redistributing traffic or allocating resources to mitigate overload. Evaluating interference levels and optimizing the radio environment may also be necessary. Finally, operators should inspect hardware and software configurations to identify and resolve potential issues, ensuring the network’s accessibility and reliability are restored.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we explore the use of MD for AD in telecommunications networks, emphasizing its efficiency and performance compared to baseline AD methods including IF, LOF, and One-Class SVM. Our approach demonstrates the ability of MD to effectively identify anomalies by leveraging domain-specific preprocessing techniques and refined feature representations. By applying dimensionality reduction to eliminate noisy features, we achieve consistent improvements in detection accuracy and computational efficiency, even as the size of the dataset increases. Notably, MD exhibits significantly faster prediction times—ranging from 1–2 s compared to minutes or hours for baseline methods—making it particularly suitable for operational networks where high-dimensional KPI data from thousands of network elements must be processed in near real time.

Cross-dataset validation experiments demonstrate that MD maintains consistent detection performance across datasets from different time periods (summer, winter, spring), with AUC values ranging from 0.89 to 0.91. This generalization capability indicates that the correlation structure between KPIs remains stable across seasonal variations, despite changes in absolute traffic volumes.

Through practical use cases, we validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach in isolating problematic network elements and pinpointing KPIs responsible for anomalies. In particular, the case study of the RACH success rate highlights how the method enables deeper insights into the root causes of network issues, guiding telecom operators toward actionable resolutions.

The unsupervised nature of the MD approach eliminates the need for labeled datasets, making it adaptable to various AD scenarios across dynamic and large-scale networks. This adaptability ensures that the approach remains relevant as networks evolve and data complexities increase.