Collaborative AI-Integrated Model for Reviewing Educational Literature †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context and Participants

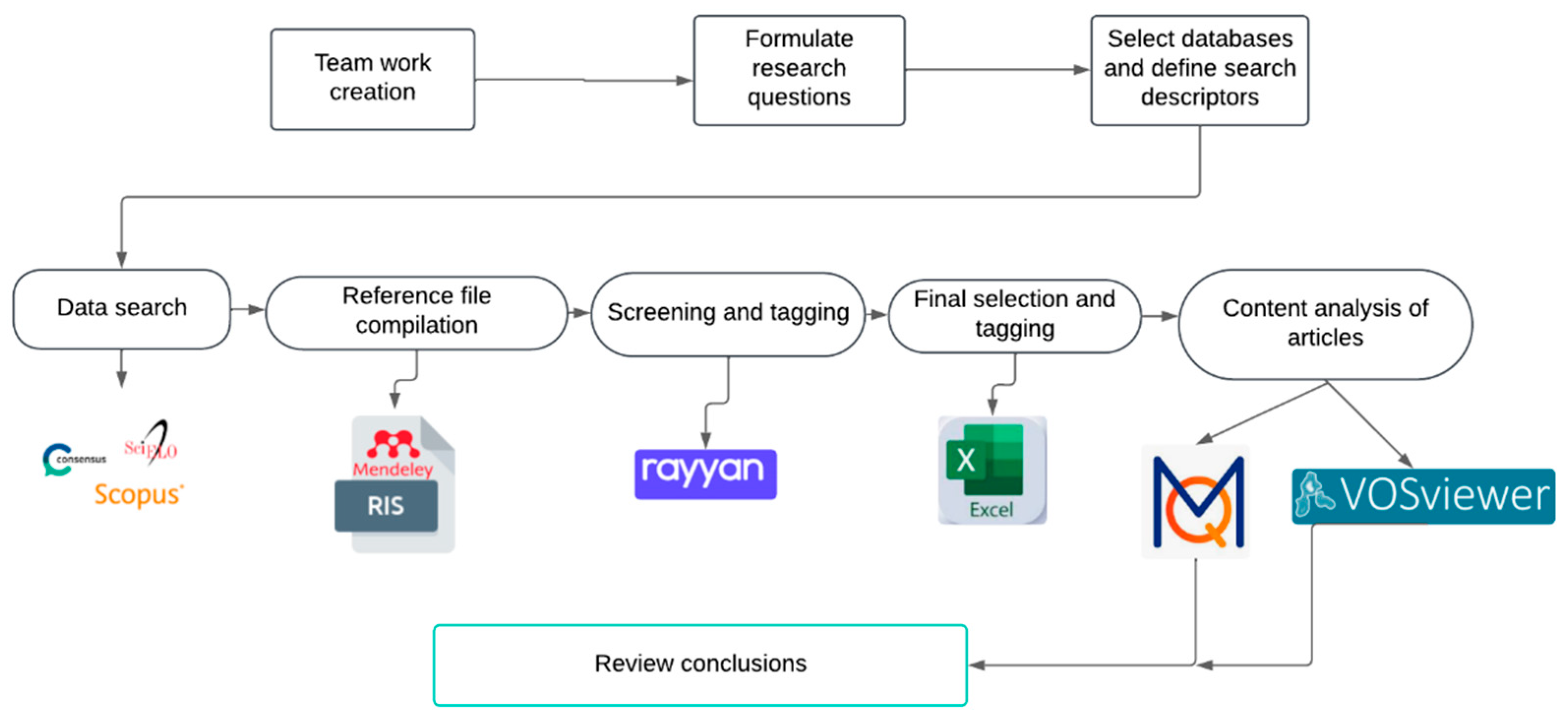

2.2. Model Design and Piloting

2.3. Instrument and Data Analysis

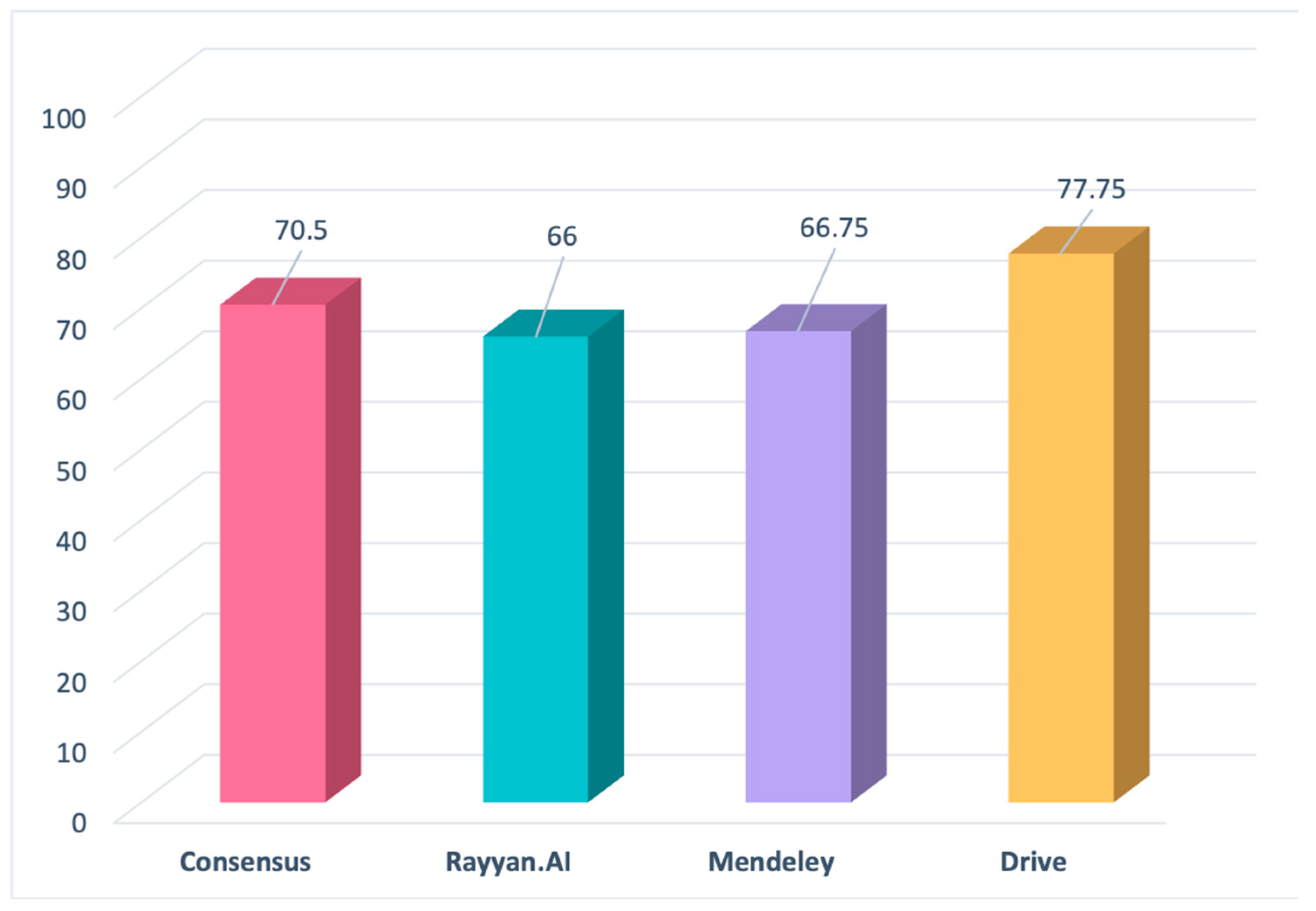

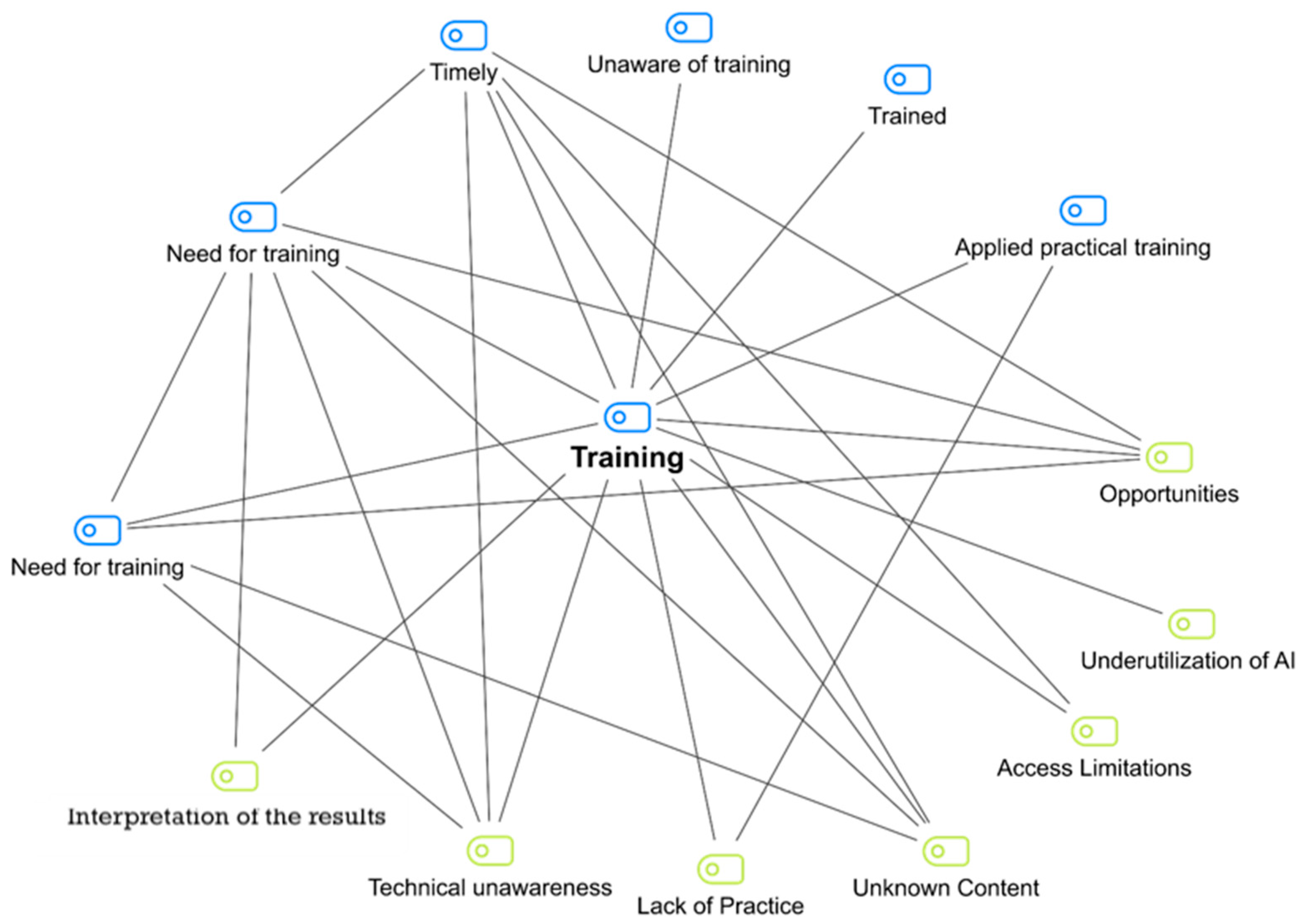

3. Results

“Efficiency for the systematization of information, i.e., filter the articles most related to the object of study, or if it is for a literature review for those that meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria.”(ID7, pos. 6, 2025)

“Automation of the research, analysis and data generation process allows researchers to focus on data interpretation. Processing large volumes of information minimizes human error, facilitates decision-making, and speeds up research. Personalization, synchronization, interdisciplinary and international collaboration”.(ID6, Pos. 5, 2025)

“Need to receive training to make proper use of the tools for collaborative work and efficient use of the tools”.(ID7, pos. 2, 2025)

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

Appendix A

References

- Baker, T.; Smith, L. Educ-AI-Tion Rebooted? Exploring the Future of Artificial Intelligence in Schools and Colleges; Nesta Foundation: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/Future_of_AI_and_education_v5_WEB.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- López de Mántaras, R.; Brunet, P. ¿Qué es la inteligencia artificial? Papeles 2023, 164, 1–9. Available online: https://www.fuhem.es/papeles_articulo/que-es-la-inteligencia-artificial/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Salas-Pilco, S.Z.; Yang, Y. Artificial intelligence applications in Latin American higher education: A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2022, 19, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, M.; Torrington, J.; Lai, J.W.; Petocz, P.; Alfano, M. How should we change teaching and assessment in response to increasingly powerful generative Artificial Intelligence? Outcomes of the ChatGPT teacher survey. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 15403–15439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocen, S.; Elasu, E.; Majeri, S.; Olupot, C. Artificial intelligence in higher education institutions: Review of innovations, opportunities and challenges. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Karadeniz, A.; Baneres, D.; Guerrero-Roldán, A.-E.; Rodríguez, M.E. Artificial Intelligence and Reflections from Educational Landscape: A Review of AI Studies in Half a Century. Sustainability 2021, 13, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, K.; Joshith, V.P. The Transformative Trajectory of Artificial Intelligence in Education: The Two Decades of Bibliometric Retrospect. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2024, 52, 376–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine Learning: Trends, Perspectives, and Prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, H. Nobel Turing Challenge: Creating the engine for scientific discovery. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 2021, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.C. Métodos e Técnicas de Pesquisa Social, 5th ed.; Atlas: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos, E.M.; Marconi, M.A. Fundamentos de Metodología Científica, 6th ed.; Atlas: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, W.C.; Colomb, G.G.; Williams, J.M. The Craft of Research, 3rd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre-López, J.; Ramírez, A.; Romero, J.R. Artificial intelligence to automate the systematic review of scientific literature. Computing 2024, 105, 2171–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TechTitute. Análisis de Datos con Inteligencia Artificial en la Investigación Clínica. 2023. Available online: https://www.techtitute.com/inteligencia-artificial/experto-universitario/experto-analisis-datos-inteligencia-artificial-investigacion-clinica (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- García-Peñalvo, F.J. Desarrollo de estados de la cuestión robustos: Revisiones Sistemáticas de Literatura. Educ. Knowl. Soc. 2022, 23, e28600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, L. Revisiones de la Literatura Con el uso de Inteligencia Artificial: Propuesta de un Nuevo Marco de Trabajo. 2025. Available online: https://www.lluiscodina.com/revisiones-literatura-ia/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Bolaños, F.; Salatino, A.; Osborne, F.; Motta, E. Artificial intelligence for literature reviews: Opportunities and challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajal-Degante, E.; Gutiérrez, M.H.; Sánchez-Mendiola, M. Hacía revisiones de la literatura más eficientes potenciadas por inteligencia artificial. Investig. Educ. Médica 2023, 12, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A.; Alani, N. Can generative AI reliably synthesise literature? Exploring hallucination issues in ChatGPT. AI Soc. 2025, 40, 6799–6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohery, M. ChatGPT in Academic Writing and Publishing: A Comprehensive Guide; Zenodo: Bruxelles/Brussel, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, J.; De Souza, M.; De Andrade Neto, A.; De Souza, B. An analysis of the generative ai use as analyst in qualitative research in Science Education. Rev. Pesqui. Qual. 2024, 12, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabashvili, I. The impact and applications of ChatGPT: A Systematic Review of Literature Reviews. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.18086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, G.; Young, P. Herramientas de inteligencia artificial en la investigación académica y científica: Normativas, desafíos y principios éticos. Medicina 2024, 84, 1036–1038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Issues and dilemmas in teaching research methods courses in social and behavioural sciences: US perspective. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2003, 6, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pole, K. Diseño de Metodologías Mixtas. Una Revisión de las Estrategias para Combinar Metodologías Cuantitativas y Cualitativas; Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente: Tlaquepague, Mexico, 2009; Available online: https://rei.iteso.mx/server/api/core/bitstreams/ee397b99-bb24-4c3e-ba94-b9dde4563026/content (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Raposo-Rivas, M.; Gallego-Arrufat, M.J.; Cebrián de la Serna, M. RedTICPraxis. Red Sobre las TIC en Prácticum y Prácticas Externas. XV Symposium Internacional Sobre el Prácticum y las Prácticas Externas. REPPE. 2019. Available online: https://riuma.uma.es/xmlui/handle/10630/18103 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Martín Cuadrado, A.M.; Pérez Sánchez, L.; Latorre Medina, M.J.; do Carmo Duarte-Freitas, M.; Sgreccia, N.; González Fernández, M.O. Generación de comunidades de conocimiento el trabajo de la RedTICPraxis. Rev. Pract. 2023, 8, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadros-Flores, P.; González-Fernández, M.O.; Pérez-Torregrosa, A.B.; Raposo-Rivas, M. Inteligencia artificial para el análisis referencial: Una experiencia colaborativa de investigación en red. In Proceedings of the P.PIC’25. Porto Pedagogical Innovation Conference, Porto, Portugal, 17–18 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- González-Fernández, M.O.; Pérez-Torregrosa, A.B.; Quadros-Flores, P.; Raposo-Rivas, M. Networking using artificial intelligence to search and classify information. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Teacher Education, Cambridge, UK, 12–14 December 2025; pp. 302–307. Available online: https://cloud.ipb.pt/f/478639e6f95346559b0b/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Brooke, J. SUS: A Quick and Dirty Usability Scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Jordan, P.W., Thomas, B., Weerdmeester, B.A., McClelland, I.L., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 1996; pp. 189–194. Available online: https://hell.meiert.org/core/pdf/sus.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Hedlefs Aguilar, M.I.; Garza Villegas, A.A. Análisis comparativo de la Escala de Usabilidad del Sistema (EUS) en dos versiones. RECI Rev. Iberoam. Cienc. Comput. Inform. 2016, 5, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R. The System Usability Scale: Past, Present, and Future. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018, 34, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, N.; Gupta, A.; Bhambra, N.; Luu, B.; Wong, S.; Maaz, M.; Fiedorowicz, J.G.; Smith, A.L.; Solmi, M. How to optimize the systematic review process using AI tools. JCPP Adv. 2024, 4, e12234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, B.; Kanbach, D.K.; Kraus, S.; Breier, M.; Corvello, V. On the use of AI-based tools like ChatGPT to support management research. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Country | University | Gender | Age | Teaching Experience | Research Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Argentina | National University of Rosario | Woman | 45 | 23 | Mathematics Education |

| 2 | Spain | University of Granada | Woman | 46 | 23 | Teacher training |

| 3 | Spain | CEU Cardenal Spinola | Woman | 55 | 30 | Education |

| 4 | Spain | University of Vigo | Woman | 56 | 30 | ICT, Practicum |

| 5 | Spain | University of Jaén | Woman | 33 | 3 | ICT, Teacher training |

| 6 | Mexico | University of Guadalajara | Woman | 51 | 24 | Education, ICT, Finance |

| 7 | Mexico | University of Guadalajara | Woman | 47 | 23 | Education, ICT |

| 8 | Mexico | University of Guadalajara | Man | 48 | 21 | ICT |

| 9 | Peru | Catholic University Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo | Woman | 47 | 27 | Education, ICT |

| 10 | Portugal | ESE Instituto Politecnico de Porto | Women | 60 | 13 | ICT, Innovation |

| Code/Subcode | Percentages | Code/Subcode | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weaknesses | 8.85% | Threats | 8.85% |

| Weaknesses > Technological | 0.00% | Threats > Restriction of access to tools | 1.77% |

| Weaknesses > Technological > Access restrictions | 1.77% | Threats > Learning to use tools | 0.88% |

| Weaknesses > Technological > Technical–Connectivity issues | 0.88% | Threats > Reliability of results/biases | 3.54% |

| Weaknesses > Skilles | 0.00% | Threats > Constructive critical attitude | 0.88% |

| Weaknesses > Skilles > Lack of knowledge | 1.77% | Threats > Absence of threat | 1.77% |

| Weaknesses > Skilles > Insufficient practice | 0.88% | Threats > Adaptation | 0.88% |

| Weaknesses > Skilles > Technical unawareness | 2.65% | ||

| Weaknesses > Interpretation of results | 0.88% | ||

| Weaknesses > Underutilization | 0.88% | ||

| Strengths | 8.85% | Opportunities | 8.85% |

| Strengths > Guidance | 0.88% | Opportunities > Ethical use | 0.88% |

| Strengths > Efficiency in data management | 3.54% | Opportunities > Automation and efficiency | 1.77% |

| Strengths > Collaborative work | 2.65% | Opportunities > Personalization | 0.88% |

| Strengths > Process automation | 1.77% | Opportunities > Data processing | 5.31% |

| Strengths > Optimization | 3.54% | Opportunities > Socialization | 2.65% |

| Opportunities > AI as assistants | 0.88% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Fernández, M.-O.; Raposo-Rivas, M.; Pérez-Torregrosa, A.-B.; Quadros-Flores, P. Collaborative AI-Integrated Model for Reviewing Educational Literature. Computers 2025, 14, 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120562

González-Fernández M-O, Raposo-Rivas M, Pérez-Torregrosa A-B, Quadros-Flores P. Collaborative AI-Integrated Model for Reviewing Educational Literature. Computers. 2025; 14(12):562. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120562

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Fernández, María-Obdulia, Manuela Raposo-Rivas, Ana-Belén Pérez-Torregrosa, and Paula Quadros-Flores. 2025. "Collaborative AI-Integrated Model for Reviewing Educational Literature" Computers 14, no. 12: 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120562

APA StyleGonzález-Fernández, M.-O., Raposo-Rivas, M., Pérez-Torregrosa, A.-B., & Quadros-Flores, P. (2025). Collaborative AI-Integrated Model for Reviewing Educational Literature. Computers, 14(12), 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120562