User Experience in Mobile Augmented Reality: Emotions, Challenges, Opportunities and Best Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Defining Mobile User Experience

2.2. Mobile Augmented Reality and User Experience

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Questions

- How do users perceive two MAR case study applications emotionally?

- What are the major opportunities and challenges associated with MAR UX?

- What are the best practices for MAR UX?

3.2. Participants

3.3. Research Methods: Case Study 1

3.3.1. Data Collection

- Question #1: What was your first impression when you saw the cat?

- Question #2: Did you find it difficult to test the application and bring the cat to the screen?

- Question #3: Would you like to have this type of application in your daily life?

- Question #4: How would you change this application?

3.3.2. Data Analysis

3.4. Research Methods: Case Study 2

3.4.1. Data Collection

3.4.2. Data Analysis

4. Case Studies

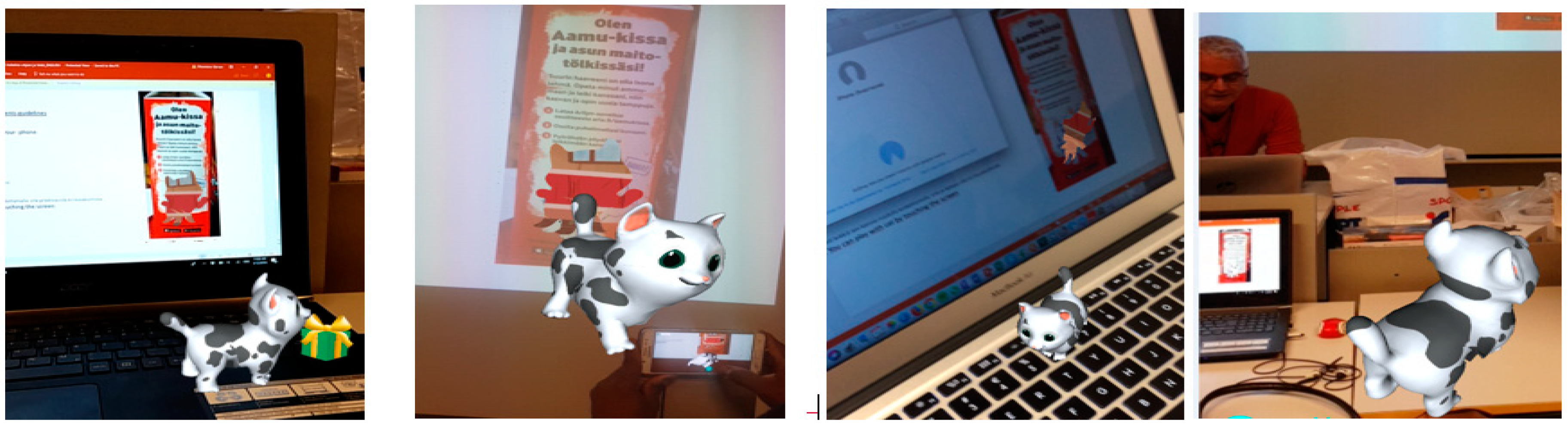

4.1. Case Study 1: Aamu Cat

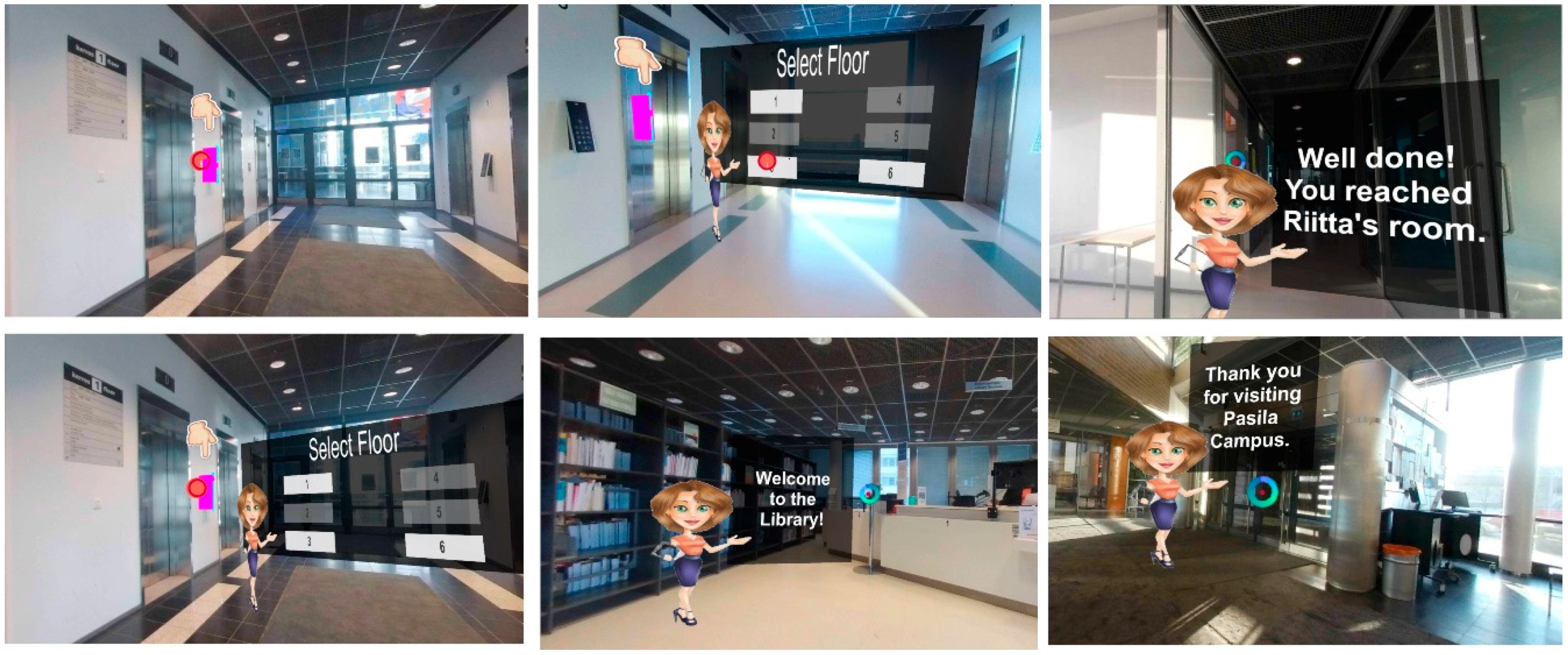

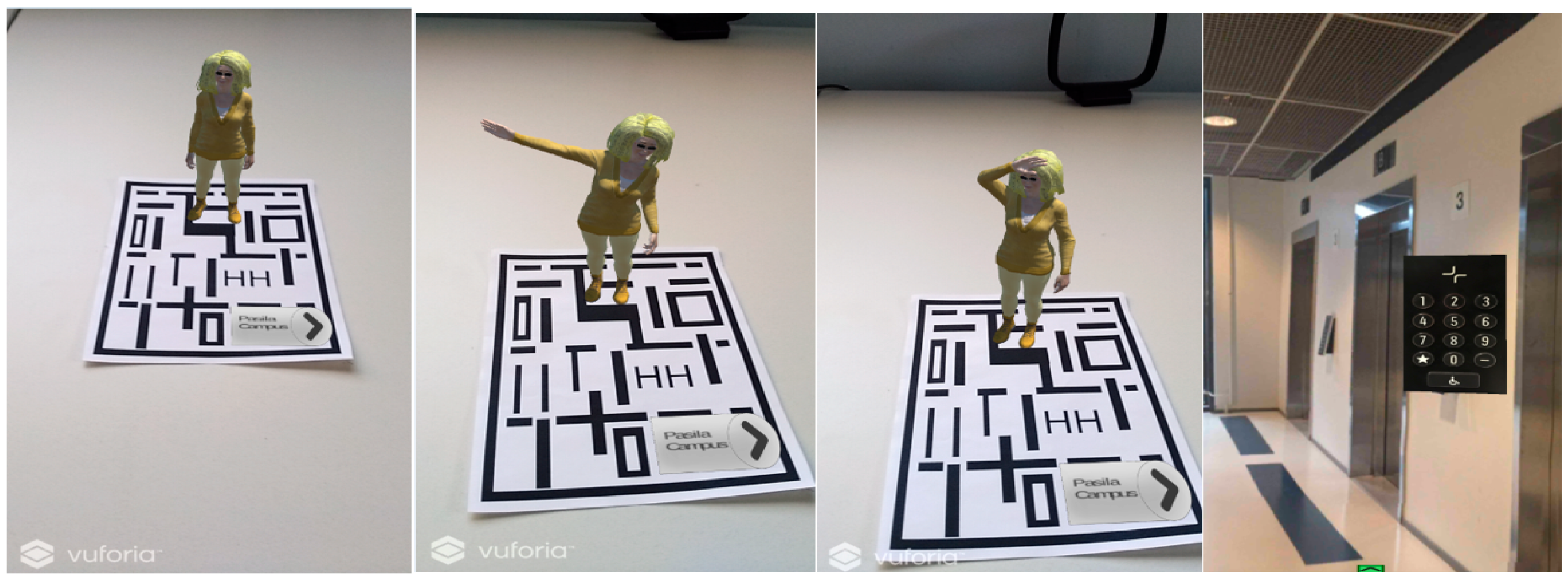

4.2. Case Study 2: Virtual Campus Tour

5. Results

5.1. Case Study 1: Aamu Cat

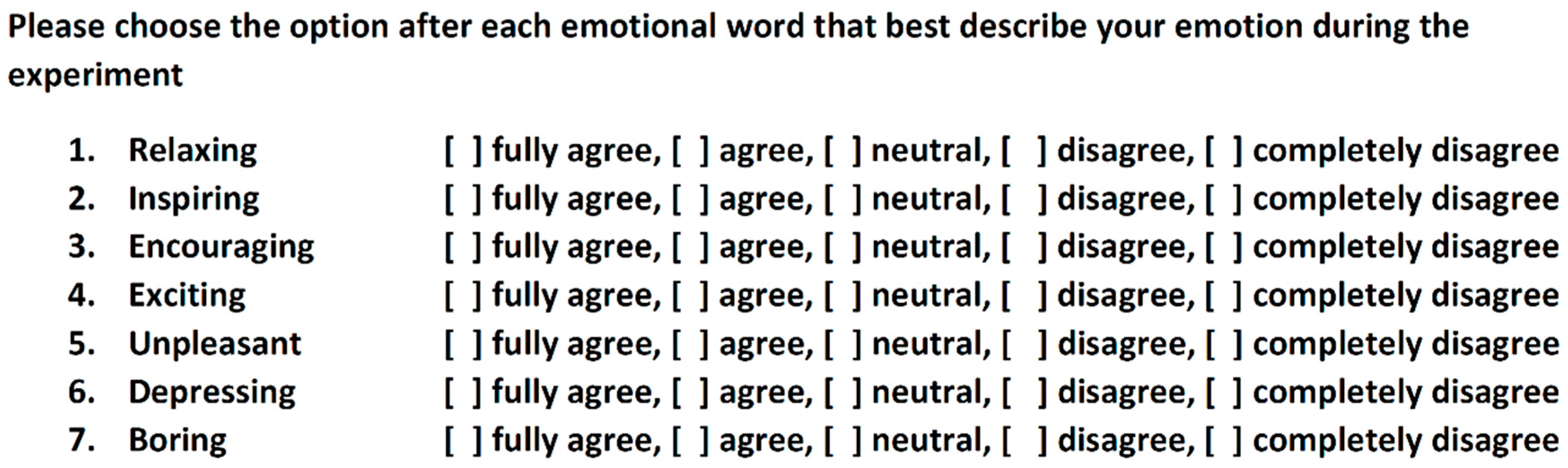

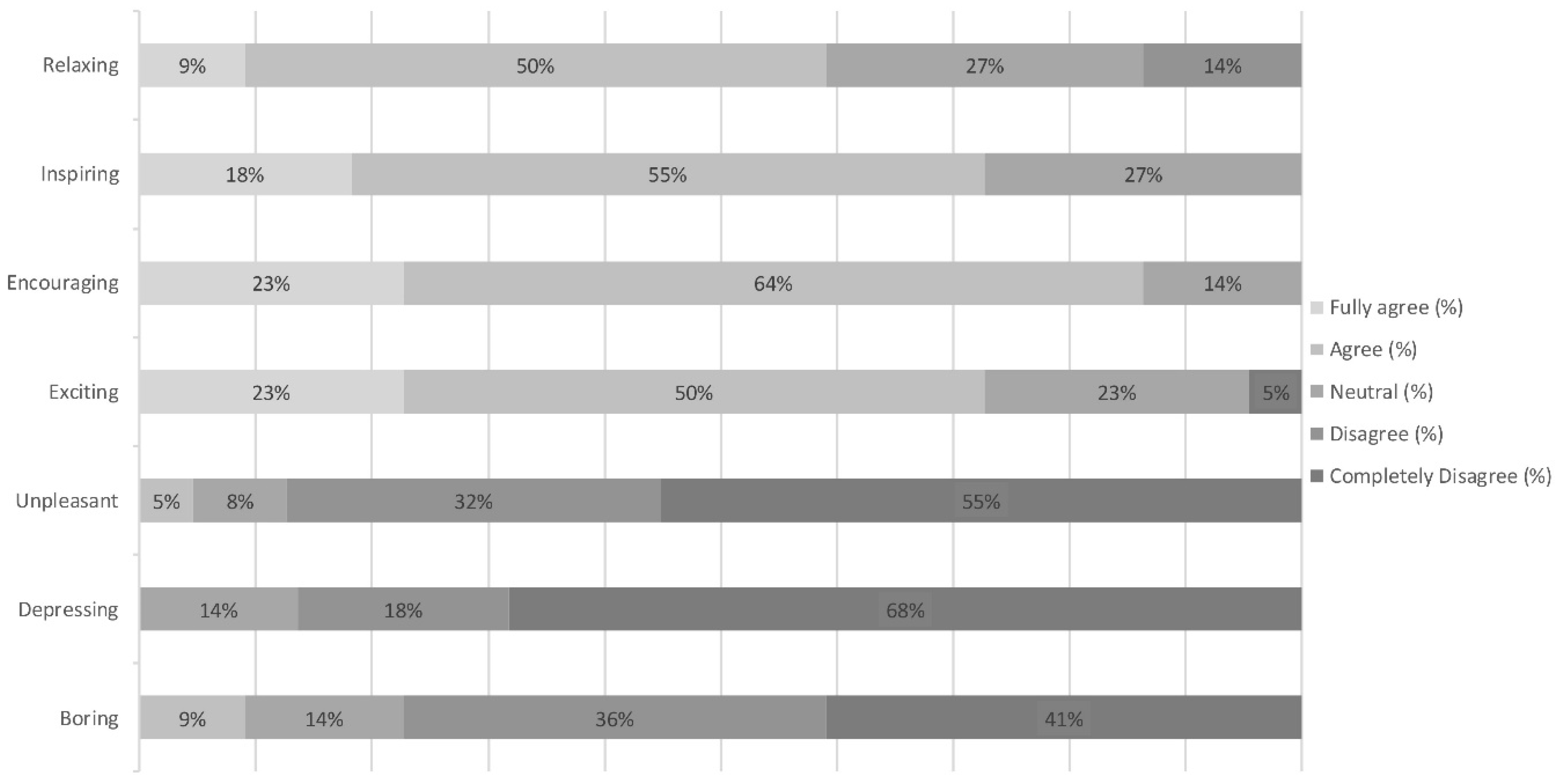

5.1.1. Questionnaire Results

5.1.2. Interview Results

“I really like its simple interactions. Cannot wait for it to kick off in everyday public places.”(Outi, 18, Female)

“The interaction was engaging and with fun, I almost knew how I should play with the cat.”(Outi, 18, Female)

“It was emotionally interesting and delightful, and having a real connection with the object, through getting it working took a while.”(Timo, 27, Male)

“Getting the cat out of the box for the first time was cool […] and its fun for a short time.”(Anastasia, 28, Female)

“The cat jumping out of the box was surprising.”(Joan, 21, Female)

“AR is more interactive, and I feel involved.”(Mia, 26, Female)

“AR is about feeling the objects.”(Timo, 27, Male)

“I’ve tried AR in a language learning application, but I dropped the language course [where the AR learning application was used], so I cannot say whether it is helpful. I prefer the normal two-dimensional (2D) view when it comes to language learning. MAR drains battery way faster.”(Janne, 24, Male)

“Maybe kids want to play with cats for minutes if not hours, I do not like to spend time with a virtual pet in my phone.”(Alexey, 21, Male)

“Choose the figure.”(Sara, 21, Female)

“Different animal, more colorful surroundings.”(Mia, 26, Female)

“More entertainment actions.”(Outi, 18, Female)

“I guess some alert that it would popup is good to have.”(Timo, 27, Male)

“Feel like this is a beta version, I want to have a more realistic figure. Seems that the cat moves very slow.”(Ivan, 21, Male)

“My first AR experience wasn’t surprising because the app lagged a bit but the cat on class today was really nice.”(Sara, 21, Female)

5.2. Case Study 2: Virtual Campus Tour

5.3. Positive Emotions Experienced in the Case Studies

6. Challenges, Opportunities and Best Practices for MAR UX

6.1. Challenges of MAR UX

6.2. Opportunities of MAR UX

6.3. Best Practices for MAR UX Design

6.4. Applying Best Practices to Virtual Campus Tour

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scholz, J.; Smith, A.N. Augmented reality: Designing immersive experiences that maximize consumer engagement. Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipper, G.; Rampolla, J. Augmented Reality: An Emerging Technologies to Guide AR; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Laine, T.H. Educational Mobile Augmented Reality Games: A Systematic Literature Review and Two Case Studies. Computers 2018, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacca, J.; Baldiris, S.; Fabregat, R.; Graf, S.; Kinshuk, D. Augmented Reality Trends in Education: A Systematic Review of Research and Applications. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2014, 17, 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.K. Augmented Reality in Education and Training. TechTrends 2012, 56, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, I. Augmented reality in education: A meta-review and cross-media analysis. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2014, 18, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lee, S.W.; Chang, H.; Liang, J. Current status, opportunities and challenges of augmented reality in education. Comput. Educ. 2013, 62, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunleavy, M.; Dede, C. Augmented Reality Teaching and Learning. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology; Spector, J., Merrill, M., Elen, J., Bishop, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 735–745. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, K.-H.; Tsai, C.-C. Affordances of Augmented Reality in Science Learning: Suggestions for Future Research. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2013, 22, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.L.; Brandt, H.; Swensen, H. Augmented Reality in science education—Affordances for student learning. Nord. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2016, 12, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotaris, P.; Pellas, N.; Kazanidis, I.; Smith, P. A systematic review of Augmented Reality game-based applications in primary education. In Proceedings of the 11th European Conference on Game Based Learning, Graz, Austria, 5–6 October 2017; pp. 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Ahonen, T. Tomi Ahonen Calls Out: Augmented Reality is the 8th Mass Medium. VR World. 2012. Available online: http://vrworld.com/2012/04/11/tomi-ahonen-calls-out-augmented-reality-is-the-8th-mass-medium/ (accessed on 20 May 2018).

- Billinghurst, M.; Clark, A.; Lee, G. A Survey of Augmented Reality. Pres. Teleoper. Virt. Environ. 2015, 8, 73–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekni, M.; Lemieux, A. Augmented Reality: Applications, Challenges and Future Trends. In Proceedings of the 13th Applied Computer and Applied Computational Science, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 23–25 April 2014; pp. 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Althoff, T.; White, R.W.; Horvitz, E. Influence of Pokémon Go on Physical Activity: Study and Implications. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tateno, M.; Skokauskas, N.; Kato, T.A.; Teo, A.R.; Guerrero, A.P.S. New game software (Pokémon Go) may help youth with severe social withdrawal, hikikomori. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 246, 848–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirin, A. From Usability to User Experience in Mobile Learning Application; Aalto University: Helsinki, Finland, 2016; p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- Paavilainen, J.; Korhonen, H.; Alha, K.; Stenros, J.; Koskinen, E.; Mayra, F. The Pokémon GO Experience. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems—CHI ’17, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 2493–2498. [Google Scholar]

- Rasche, P.; Schlomann, A.; Mertens, A. Who Is Still Playing Pokémon Go? A Web-Based Survey. JMIR Ser. Games 2017, 5, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritsos, P.; Ritsos, D.; Gougoulis, A. Standards for Augmented Reality: A User Experience perspective. Stand. Meet. 2011, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, T.; Lagerstam, E.; Kärkkäinen, T.; Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K. Expected user experience of mobile augmented reality services: A user study in the context of shopping centres. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2013, 17, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roto, V.; Law, E.; Vermeeren, A.; Hoonhout, J. User Experience White Paper—Bringing Clarity to the Concept of User Experience. Available online: http://www.allaboutux.org/files/UX-WhitePaper.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2018).

- Tokkonen, H.; Saariluoma, P. How User Experience is Understood? In Proceedings of the Science and Information Conference (SAI), London, UK, 7–9 October 2013; pp. 791–795. [Google Scholar]

- Carlos, J.; Nicolás, O.; Aurisicchio, M. A Scenario of User Experience. Design 2011, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hassenzahl, M. User experience (UX): Towards an experiential perspective on product quality. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference Association Francophone d’Interaction Homme-Machine—IHM ’08, Metz, France, 2–5 September 2008; pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hassenzahl, M.; Tractinsky, N. User experience—A research agenda. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2006, 25, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, L.T. User experience evaluation methods for mobile devices. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Innovative Computing Technology, London, UK, 29–31 August 2013; pp. 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Väätäjä, H.; Roto, V. Mobile questionnaires for user experience evaluation. In Proceedings of the 28th of the international conference extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems—CHI EA ’10, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–15 April 2010; p. 3361. [Google Scholar]

- Pelet, J.-É.; Taieb, B. Enhancing the Mobile User Experience Through Colored Contrasts. In Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology, 4th ed.; 2018; pp. 6070–6082. [Google Scholar]

- Dirin, A.; Nieminen, M. mLUX: Usability and User Experience Development Framework for M-Learning. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2015, 9, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, S.; Rohaya Bt Awang Rambli, D. User experience of mobile augmented reality: A review of studies. In Proceedings of the 2014 3rd International Conference on User Science and Engineering (i-USEr), Shah Alam, Malaysia, 2–5 September 2014; pp. 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Arth, C.; Grasset, R.; Gruber, L.; Langlotz, T.; Mulloni, A.; Wagner, D. The History of Mobile Augmented Reality. Comput. Graph. Vis. 2015, 2, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Prochazka, D.; Stencl, M.; Popelka, O.; Stastny, J. Mobile augmented reality applications. In Proceedings of the Mendel 2011 17th International Conference on Soft Computing, Brno, Czechoslovakia, 15–17 June 2011; pp. 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, R.A.; Mohamed, H.; Hussin, A.R.C. Mobile Augmented Reality Tourism Application Framework. In Recent Trends in Information and Communication Technology: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference of Reliable Information and Communication Technology (IRICT 2017); Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, T.; Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K. Expected User Experience with Mobile Augmented Reality Services. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Stockholm, Sweden, 30 August–2 September 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, T.; Chung, N.; Leue, M.C. The determinants of recommendations to use augmented reality technologies: The case of a Korean theme park. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J. A framework for context immersion in mobile augmented reality. Autom. Constr. 2013, 33, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, S.; Awang Rambli, D.R. Multi-layered Mobile Augmented Reality Framework for Positive User Experience. In Proceedings of the The 2th International Conference in HCI and UX on Indonesia 2016—CHIuXiD ’16, Jakarta, Indonesia, 13–15 April 2016; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, A.; Sharma, N.K.; Gupta, P.; Saxena, P.; Kumar Pal, R.; Mehrotra, S.; Nair, P.; Wadhwa, M. Mobile Application Development with Augmented Reality. Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2014, 2, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. How many test users in a usability study. 2012. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-many-test-users/ (accessed on 20 May 2018).

- Falk, E.B.; O’Donnell, M.B.; Tompson, S.; Gonzalez, R.; Dal Cin, S.; Strecher, V.; Cummings, K.M.; An, L. Functional brain imaging predicts public health campaign success. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldana, J. An Introduction to Codes and Coding. In The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2015; p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, G.C.; Vogel, R.S.; Coffman, S.G. Think-aloud approaches to cognitive assessment and the articulated thoughts in simulated situations paradigm. J. Consul. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 65, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmigniani, J.; Furht, B.; Anisetti, M.; Ceravolo, P.; Damiani, E.; Ivkovic, M. Augmented reality technologies, systems and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2011, 51, 341–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case Study | Participants | N | Males | Females | Age (Average) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Study 1 | Haaga-Helia students | 22 | 13 | 9 | 18–31 (23) |

| Case Study 2 | Haaga-Helia students (4) and other students (2) | 6 | 2 | 4 | 20–34 (25) |

| Plan category | Details |

|---|---|

| Equipment: | Mobile phone (Samsung Galaxy A8, Android), test instructions |

| Observations: | Notes of the user’s actions and the time it takes for the user to complete the tasks. |

| Pre-test: | Introduction and application orientation |

| Tasks: | Go to Riitta’s room on the 6th floor. Proceed to the library and be welcomed by the guide Go to the 1st floor lobby entrance/ exit door |

| Test Method: | Facilitator instructs the users of the tasks. |

| Data Collection: | Video and audio recording, written notes, think-aloud, interviews |

| Interview questions: | Comments about the hardware Comments about the app. What would they change? Negative and positive aspects? Comments about how users felt while accomplishing the tasks. Emotions? Is it fun to use, interesting, anything surprising? Other comments |

| Introduction: | 5 min |

| Test Tasks: | 4–15 min (Usability and UX) |

| Debriefing: | 5–10 min |

| Reporting | 120 min |

| Total: | 15–30 min per user 1.5–3 h for 6 users |

| Emotional Impact | Case Studies |

|---|---|

| Relaxing | The cat made the participants feel relaxed while they interacted with the application. Aligned with this, Riitta’s avatar in Case Study 2 provided a friendly and relaxing environment to the participants. |

| Inspiring | The cat avatar and the augmented objects inspired the participants to explore more the functionalities of the application. This is one reason why it is recommended to use avatars to engage users emotionally. |

| Encouraging | The participants were encouraged to try and explore further interaction with the cat or wait to see what the cat avatar does next. Similarly, in the second case study, the avatar helped the participants feel that somebody was there to help, thus encouraging them to explore further and not being afraid of making mistakes or being lost. |

| Exciting | The participants found the MAR applications exciting. The excitement in the first case study was on the user expectation as to what the cat avatar might do next. The excitement in the second case study was based on the avatar’s behavior and interaction with users. |

| Delightful | The evaluation results demonstrate that a well-designed interactive avatar and virtual objects made the participants delighted. |

| Fun | In the first case study, almost all participants (except one) pointed out the fact that they had fun working with the application because of the cat. |

| Surprising | The participants were surprised by MAR and the virtual objects (e.g., Aamu cat). |

| Challenges | Description |

|---|---|

| Physical | Often, almost the whole body needs to be involved while interacting with a MAR application. Users need to interact and communicate with the application by clicking, tapping, moving, gesturing or giving voice commands. In non-MAR applications, tapping or gestures are typically used. |

| Mental | New MAR applications often require that the user installs them first and possibly require special glasses. For example, in the first case study, the participants had to install Arilyn before they were able to scan the cat. Installing new and possibly unknown applications requires extra effort and trust from users. The user should be convinced of the necessity of installing the application. Another mental challenge is the cognitive load caused by the bridging of the virtual and the real world via rich multimedia content. Moreover, the new way of thinking about content and interacting with it can also be mentally exhausting. |

| Prototyping | Technologies for supporting MAR application design are still in an early phase despite recent developments. For example, we still lack rapid prototyping tools to design low- and high-fidelity prototypes. |

| Technical | There still are many technical challenges associated with MAR UX that may affect the emotions experienced by the user, including, but not limited to battery drain, required processing power (i.e., how to make it available on low-end devices), screen size and the type of tracking (e.g., marker-based, markerless). |

| User interface | Designers have already managed to construct user interface and interaction metaphors for non-AR mobile applications. All mobile application design metaphors are not necessarily applicable to MAR applications; hence, new interface and interaction metaphors specific for MAR applications are needed. |

| Development | To develop a robust MAR application, application developers must utilize multiple integrated development environments. For example, in the second case study, we worked with Unity 3D, Vuforia AR and Visual Studio. |

| UX design | The mindset change from mobile application to MAR concept design is associated with some challenges. Designers are required to adjust their design approaches, which are based on 2D sketching of non-AR objects using a pen and paper or mock-up tools, towards sketching of 3D scenes and objects that are viewed through a 2D perspective (i.e., the camera). Connected to this, as mentioned above, MAR UX designers lack robust prototyping tools to create prototypes for MAR objects and interaction. |

| Timing | The experiment demonstrated that the participants get frustrated if MAR objects take too much of their time, especially when the application’s purpose is to entertain the user. The optimal presentation time needs to be carefully assigned depending on the context and the target user group. |

| Opportunity | Description |

|---|---|

| Marketing Potential | MAR creates a unique opportunity for practitioners to promote products and services. Applying MAR in product advertisements helps users perceive the product better. Furthermore, it helps users become attached to and involved more closely with the product. For example, the cat avatar aims to establish emotional engagement towards the milk brand. Traditionally, this type of emotional engagement with tangible products has been feasible to achieve through video advertisements. MAR can enable this emotional engagement through richer, two-directional interaction (e.g., eyes, ears, hands). |

| Emotional Engagement | Emotional engagement, as mentioned above, is a key deliverable that MAR can bring to the user. Emotional engagement was also evident in our evaluation results. For example, some participants in the first case study were observed to be holding an empty milk package with smiles on their faces. |

| User Interface | MAR provides unique opportunities to create novel user interfaces. Voice commands and touching MAR objects (e.g., virtual buttons) are examples of novel UI components that can be associated with MAR applications. |

| Interaction | AR enables unique interaction experiences for mobile applications that previously were not feasible, such as voice commands, natural communication with an avatar and rich visualization of UI instead of having text-only labels and 2D graphics to guide the user. |

| Experience Development | MAR enables designers to create context-sensitive illusions that ease the cognitive process for complex tasks, such as when an interior designer is fitting furniture in a room or when an architect is illustrating architectural models on top of a real-world view of a vacant plot. |

| Best Practice | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial correspondence | MAR object dimensions and location should match the intended target used on top of the real world. | In Case Study 2, the MAR panel dimensions and locations were inaccurate, thus causing inconvenience to the participants. |

| Tolerance to movement | MAR objects should be tolerant to camera movement. For example, if the marker goes out of the camera view, the MAR object should remain visible for a period of time. | In Case Study 1, the cat avatar was sensitive to movement, as it disappeared from the screen when the participants slightly moved their smartphones. |

| Object detail | The details of MAR objects should be sufficiently high (within the limits of the target hardware) to make them recognizable and appealing. | The avatar in Case Study 2 was a 2D cartoon object. The cat avatar in Case Study 1 occupied the screen properly, which makes the impression to the participants that the cat is the only interactive object in the screen. |

| Object correspondence | Establishing a correspondence between a MAR object and a real-world object creates a metaphorical link that increases familiarity and might also lower the learning curve. | The avatar in Case Study 2 had very little resemblance to Riitta, the academic advisor at Haaga-Helia. |

| Natural interaction | Allow users to interact with MAR content by multiple natural methods (e.g., speech, touch, gestures), thus promoting realism. | The interaction in the first and second case studies was based on a touch-based user interface, which is a typical approach in MAR applications [3]. |

| Personalized experience | Making the MAR experience personal to each user increases the likelihood for emotional engagement. This can be done, for example, by allowing the user to customize the application or automatically adapting the application based on the user’s context and preferences. | Both case studies provided a one-size-fits-all experience to all users. The participants were not able to change preferences or otherwise customize the content. In Case Study 1, some participants suggested to add a personalization feature, such as choosing a dog avatar instead of a cat avatar. |

| Emotion-evoking avatar | It is recommended to include an avatar in MAR applications to make interaction with the application more natural. Moreover, the avatar should have emotion-evoking properties, such as pleasing appearance and body language that signal how the avatar feels. | The cat in the first case study was found to be appealing and was able to evoke emotions among the participants. In Case Study 2, the Riitta avatar did not achieve this, possibly due to the avatar design and lack of interaction. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dirin, A.; Laine, T.H. User Experience in Mobile Augmented Reality: Emotions, Challenges, Opportunities and Best Practices. Computers 2018, 7, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers7020033

Dirin A, Laine TH. User Experience in Mobile Augmented Reality: Emotions, Challenges, Opportunities and Best Practices. Computers. 2018; 7(2):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers7020033

Chicago/Turabian StyleDirin, Amir, and Teemu H. Laine. 2018. "User Experience in Mobile Augmented Reality: Emotions, Challenges, Opportunities and Best Practices" Computers 7, no. 2: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers7020033

APA StyleDirin, A., & Laine, T. H. (2018). User Experience in Mobile Augmented Reality: Emotions, Challenges, Opportunities and Best Practices. Computers, 7(2), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers7020033