1. Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (Industry 4.0) has fundamentally altered the competency profile required for modern engineering professionals [

1,

2]. The recent literature suggests that AI-driven analytics and connectivity are becoming central to industrial efficiency, transforming how knowledge is applied across sectors [

3]. Beyond traditional technical skills, engineers in fields such as Industrial, Environmental, and Electrical engineering are now expected to possess distinct digital capabilities, particularly in the Internet of Things (IoT), Cloud Computing, and Big Data acquisition [

4,

5]. This paradigm shift demands that higher education institutions move beyond theoretical instruction to provide hands-on experiences that simulate complex, real-world ecosystems [

6,

7].

However, the pedagogical integration of these technologies into non-computer science curricula remains a complex challenge. While Computer Science students typically possess a strong foundation in logic and syntax, students from other engineering disciplines often perceive programming as an auxiliary tool rather than a core competency [

8,

9]. This gap is critical, as sustainable development in industrial engineering now relies heavily on these digital skills [

10]. Consequently, traditional “bottom-up” teaching methods, which focus heavily on syntax before application, often lead to high attrition rates and low motivation among non-CS majors [

11,

12].

Project-Based Learning (PBL) has emerged as the dominant methodological framework to bridge this gap [

13,

14]. By situating technical learning within the context of real-world problem solving, PBL aims to increase motivation and relevance. Recent studies in IEEE Access and MDPI Education Sciences have highlighted the effectiveness of PBL in IoT education for fostering scientific creativity and decision-making skills [

15,

16]. Nevertheless, the current literature tends to treat “engineering students” as a monolithic group, often overlooking the distinct cognitive styles and professional expectations inherent to different engineering specializations [

17,

18]. A “one-size-fits-all” approach to teaching IoT may fail to resonate equally with an Industrial Engineer focused on process optimization and an Environmental Engineer focused on ecosystem monitoring [

19].

Moreover, the democratization of Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) technologies through Open-Source Hardware (OSH) has created a unique pedagogical opportunity. Historically, training in industrial automation relied on expensive Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) and proprietary SCADA systems, often restricting hands-on access to a few laboratory sessions per semester. However, the emergence of high-performance, low-cost microcontrollers like the ESP32—which features dual-core processing and integrated Wi-Fi/Bluetooth—allows for a “one-kit-per-student” model [

20,

21].

The shift from shared laboratory equipment to personal, portable hardware is not merely a logistical convenience; it represents a fundamental change in the learning ecosystem. It enables “ubiquitous experimentation,” where students can test, fail, and debug their systems in real-world environments (e.g., their homes or local gardens) rather than idealised laboratory conditions [

22]. Yet, despite the availability of this hardware, the pedagogical strategies to effectively deploy it across non-computer engineering disciplines remain underexplored. A critical question arises: does the sheer availability of low-cost technology translate automatically into competency acquisition, or does it require a discipline-specific scaffolding to prevent cognitive overload, validated through computational thinking assessments [

23]?

This study aims to analyze the implementation of an IoT-focused PBL module across three distinct student cohorts (NRCs) at Universidad Continental in Huancayo, Peru. The intervention involved second- and third-year students from Industrial, Environmental, Enterprise, and Electrical Engineering programs. Unlike abstract simulations, students were tasked with developing low-cost ESP32-based solutions for the agricultural and beekeeping sectors in the Junín region, sectors critical to the local economy and aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) [

24,

25].

We present a comparative analysis of student outcomes, technical adherence, and satisfaction rates across three distinct course sections (NRC-33561, NRC-33562, and NRC-33563). By leveraging evidence derived from 95 active participants and their final prototype deployments, this paper provides empirical evidence that the “success” of IoT education depends heavily on tailoring the pedagogical approach to the specific engineering discipline [

26,

27].

2. Theoretical Framework

Project-Based Learning (PBL) is recognized as a learner-centred pedagogical approach where students construct knowledge by engaging with real-world challenges [

13,

28]. In engineering education, PBL is particularly effective because it simulates professional practice, shifting the focus from passive content absorption to active problem resolution. Recent meta-analyses indicate that PBL significantly improves long-term retention of STEM concepts compared to traditional lecturing [

29].

For non-computer science majors, PBL serves as a scaffold that lowers the barrier to entry for complex topics like programming and electronics, allowing students to contextualize code as a tool for solving disciplinary problems rather than an end in itself [

8,

30].

2.1. Industry 4.0 and the “T-Shaped” Engineer

The rise of Industry 4.0 has created a demand for “T-shaped” professionals: engineers who possess deep knowledge in their specific vertical discipline (e.g., Industrial processes or Environmental systems) but also have broad, horizontal skills in digital technologies such as IoT and Big Data [

4,

31]. Integrating IoT competencies into the curriculum requires addressing three distinct layers of abstraction:

- 1.

Physical Layer: Understanding sensors and actuators [

4].

- 2.

Network Layer: Managing data transmission (e.g., Wi-Fi, MQTT) [

32].

- 3.

Application Layer: Making decisions based on data [

33].

Research by [

34] indicates that engineering students often struggle to integrate these layers without a coherent pedagogical model. By utilizing low-cost modular hardware (such as ESP32 and Arduino), educators can demystify the “black box” of technology [

4,

35].

2.2. Disciplinary Variations in Technology Adoption

A critical yet often overlooked aspect of engineering education is the epistemological difference between disciplines [

36].

Industrial Engineers view technology as a means to optimize efficiency, focusing on the systemic impact of data [

37].

Environmental Engineers view technology as a tool for monitoring, prioritizing data accuracy and sensor reliability [

38].

Electrical/Electronic Engineers focus on the intrinsic operation, prioritizing circuit efficiency [

39].

This study posits that these disciplinary predispositions influence how students perceive and succeed in a unified IoT course [

19].

2.3. Cognitive Dissonance in Non-Computer Science Majors

A significant barrier to IoT adoption in traditional engineering disciplines is the cognitive dissonance experienced when transitioning from deterministic physical systems to stochastic digital systems [

4]. In traditional curricula, such as Civil or Environmental Engineering, models are often static or governed by visible physical laws (e.g., fluid dynamics, thermodynamics). In contrast, IoT systems introduce layers of abstraction (firmware, network protocols, and cloud APIs) where failures are often invisible (e.g., a memory leak or a dropped MQTT packet).

Recent pedagogical studies suggest that this “invisibility of failure” causes higher anxiety in students accustomed to tangible feedback [

8]. For an Industrial Engineer, a process bottleneck is visible; for an Electrical Engineer, a short circuit is measurable. However, for a novice IoT developer, a segmentation fault in C++ (common in ESP32 programming) provides no immediate physical feedback. Therefore, the pedagogical framework must not only teach syntax but also “epistemic fluency”, the ability to switch between knowing how to wire a sensor and knowing why a data packet failed to transmit. This study posits that the dashboard serves as the bridge for this epistemic gap, rendering the invisible software processes visible through real-time data visualization.

From a computational thinking perspective, the intervention engaged students in core practices such as decomposition (separating sensing, communication, and decision logic), abstraction (mapping physical phenomena to digital representations), and algorithmic thinking (designing conditional control logic). The technical rubric operationalized these practices by rewarding modular firmware design, non-blocking control structures, and evidence-based decision rules, thereby linking computational thinking directly to observable artefact-level outcomes.

3. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at Universidad Continental (Huancayo, Peru) during the academic semester 2024-I. The intervention was embedded within regular semester-long courses, with an average workload of 4 contact hours per week (2 h of lectures and 2 h of laboratory sessions), complemented by independent project work. None of the participating students had received formal instruction in IoT systems prior to the course; however, all cohorts had previously completed at least one introductory programming course and basic electronics modules according to their respective curricula (no first-year students were included in the study).

The intervention was embedded in regular semester coursework (16 weeks) and followed the official syllabus for each NRC. The weekly workload comprised 4 contact hours (lectures and guided laboratory sessions) and an estimated 8 h of autonomous teamwork devoted to prototyping, debugging, and dashboard configuration. Student teams were formed with 3–4 members and worked on a single ESP32-based solution from problem framing to field validation.

Across all cohorts, students were expected to have completed foundational coursework in introductory programming and basic electronics prior to enrolment. The intervention did not assume prior expertise in IoT platforms; instead, it introduced the sensing-to-cloud pipeline during the first half of the semester through guided exercises (sensor reading, Wi-Fi connectivity, and basic telemetry publishing). To improve comparability across NRCs, the instructional modules on modular firmware design and non-blocking control structures were standardized (

Section 3.1).

Although students shared formal prerequisites, we did not administer a dedicated pre-intervention diagnostic test on IoT-specific competencies. This is a limitation that may affect the granularity of baseline comparability across cohorts. To mitigate this threat, the intervention standardized the core technical instruction (e.g., non-blocking logic, modular firmware structure, and telemetry publishing) and evaluated learning outcomes through artefact-based rubric scoring and post-intervention survey measures.

The total sample consisted of 95 students (

). To analyze the impact of disciplinary background, the analysis was stratified across three distinct academic sections (NRCs), detailed in

Table 1. Participants were enrolled in discipline-specific IoT-related courses typically offered in the second and third year of their degree programs, according to each curriculum.

To address potential confounding variables regarding the `Mixed’ composition of Group B (NRC-33562), it is important to note that this cohort was composed of 26 Electrical Engineering students and 6 Mechatronics Engineering students. Given that both curricula share a strong foundation in circuit theory and low-level logic, they were treated as a single unit of analysis with a hardware-centric profile.

3.1. Pedagogical Design: The PBL Framework

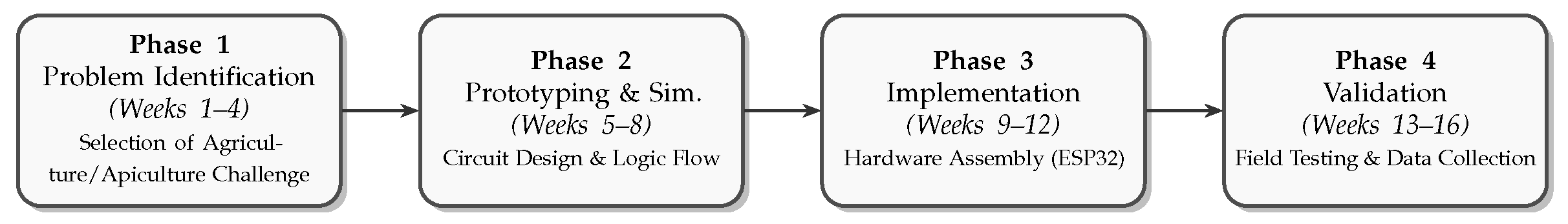

The intervention followed a four-stage PBL framework designed to transition students from abstract conceptualization to physical validation, spanning 16 weeks (

Figure 1). This structure aligns with the CDIO (Conceive–Design–Implement–Operate) initiative tailored for IoT education.

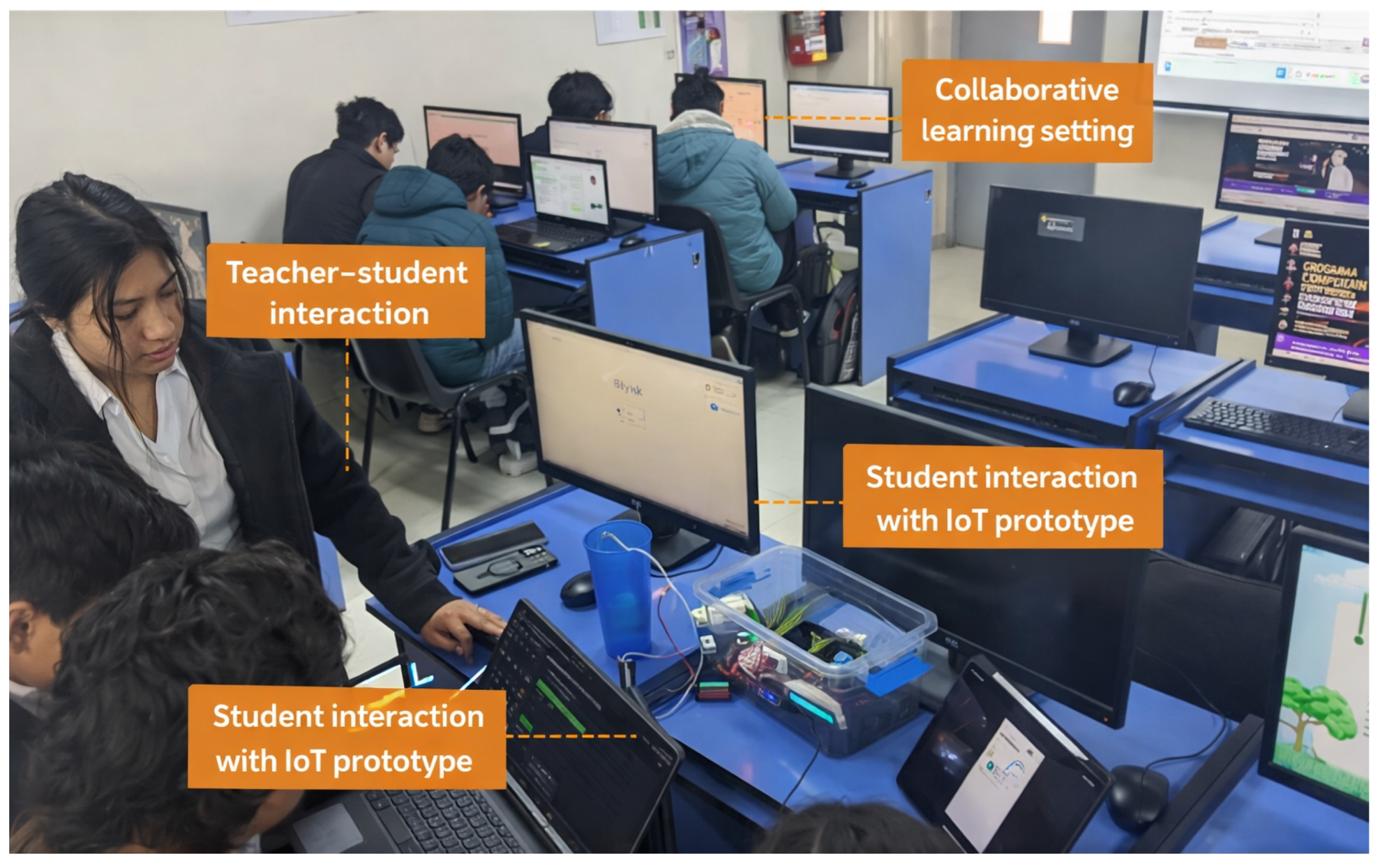

Figure 2 illustrates the authentic instructional setting in which the Project-Based Learning (PBL) intervention was implemented. The image captures multiple student teams working concurrently under a one-kit-per-team model, combining hands-on interaction with ESP32-based IoT hardware, real-time monitoring through cloud dashboards, and collaborative problem-solving activities. This visual evidence contextualizes the experimental deployment within a regular classroom environment, highlighting the integration of physical prototyping, digital interfaces, and instructor–student interaction that characterized the learning experience.

During Phase 1, students engaged with local stakeholders in the Junín region to elicit domain requirements and contextual constraints for their IoT solutions.

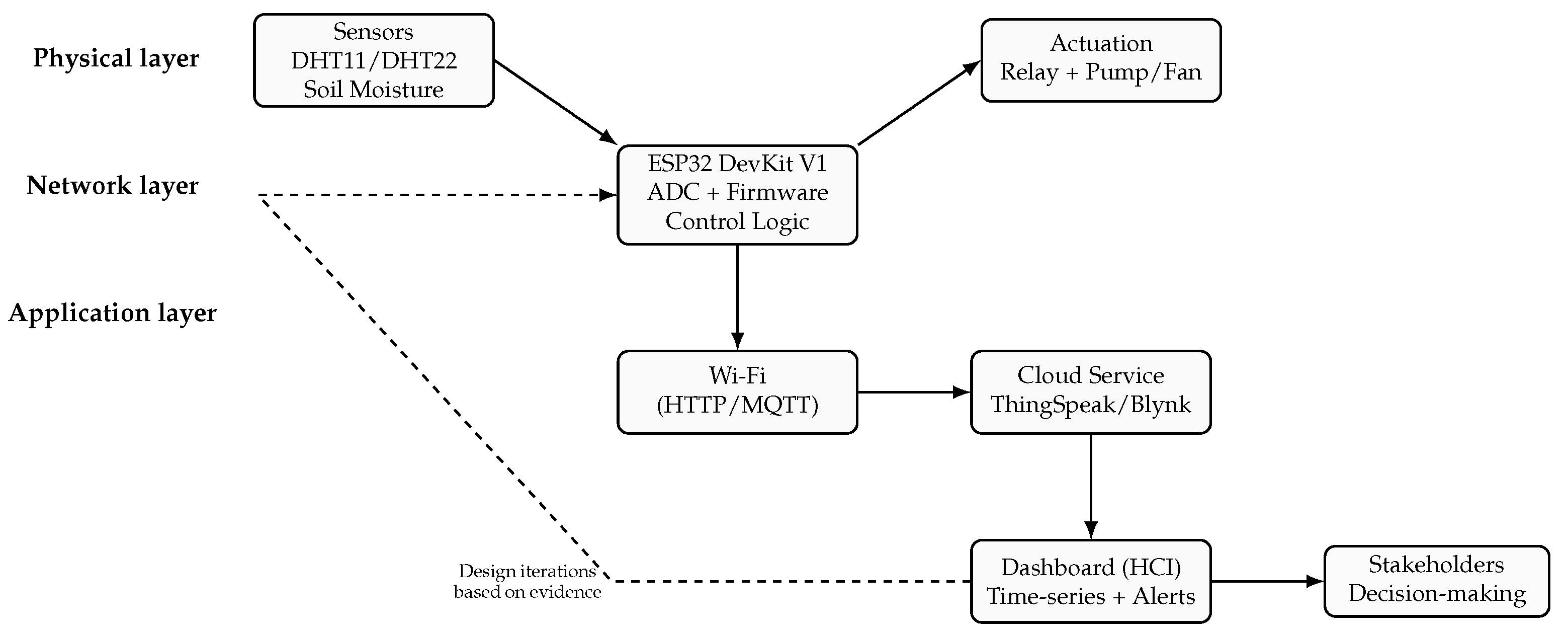

Figure 3 summarizes the complete sensing-to-cloud pipeline implemented during the intervention, from data acquisition at the physical layer to stakeholder interaction at the application layer. The mandatory use of cloud platforms such as ThingSpeak or Blynk was intentionally enforced to ensure hands-on learning of network communication protocols and data transmission mechanisms [

40,

41].

All course sections employed an equivalent dashboard structure and interaction logic, differing only in project-specific variables and alert thresholds. This design choice ensured that observed differences in performance and learning outcomes could be attributed to disciplinary background and problem framing rather than disparities in interface availability or system functionality.

To ensure the internal validity of the study, the instructional material delivered during the ’Prototyping & Simulation’ phase was standardized across all sections. Specifically, the modules covering non-blocking code structures (transitioning from delay()to millis()) were identical in duration and content for all three NRCs, isolating student disciplinary background as the primary independent variable for the observed differences in code structure.

3.2. Hardware Architecture

To minimize confounding variables, all teams utilized a standardized Low-Cost IoT Kit based on the ESP32 DEVKIT V1 [

42]. This microcontroller is increasingly preferred in academic settings over Arduino due to its dual-core architecture and native Wi-Fi/Bluetooth capabilities [

20,

43].

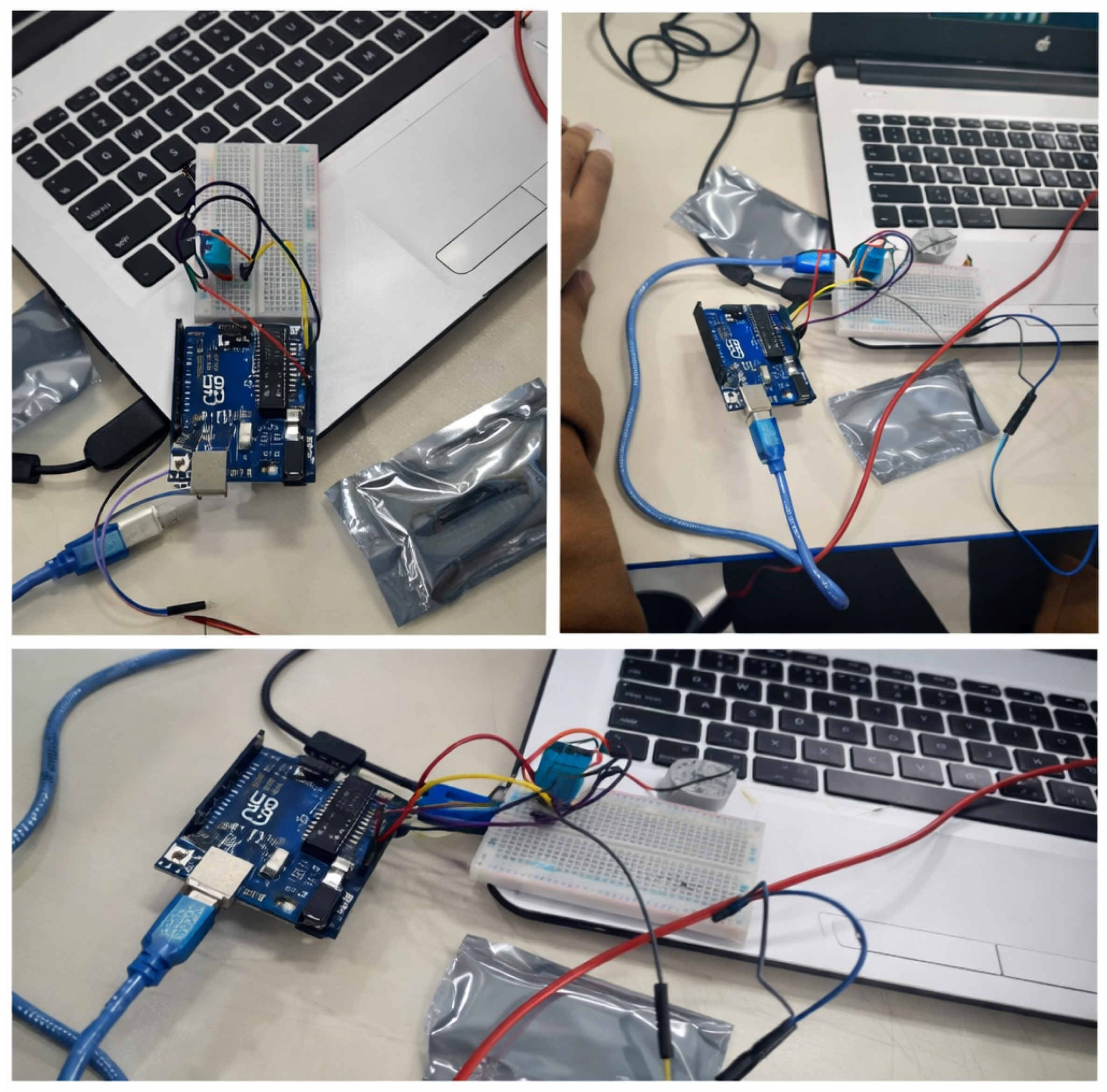

Figure 4 shows representative bench-top prototypes developed by student teams. The figure is included to illustrate typical implementations under the shared ESP32 sensing-to-cloud architecture, while allowing variation in sensors and actuation components according to each project’s agricultural or apicultural context. The figure is not intended to rank prototypes, but to document implementation diversity under a standardized kit.

3.3. Assessment Instruments and Validation

To ensure the reliability of the comparative analysis, two distinct evaluation instruments were designed and validated prior to the intervention: a Technical Rubric for the artefacts and a Psychometric Survey for student perception.

3.3.1. Technical Evaluation Rubric

The physical prototypes and their associated code were evaluated using a weighted rubric designed to measure competency across the three IoT layers (Physical, Network, Application). The rubric (detailed in

Table 2) was calibrated to penalize “spaghetti code” and reward modularity, a critical skill for Industry 4.0 scalability. Instructors performed a double-blind grading process on a random sample of 20% of the projects to ensure inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s Kappa

).

Importantly, the rubric was designed to assess integration and implementation quality rather than reproduction of a provided template. Instruction covered the underlying principles (e.g., modular design and non-blocking execution), but students were not given a complete reference implementation for the final system. Teams developed their own firmware architecture, reconnection strategies, telemetry payload structures, and dashboard logic, which resulted in observable variance across cohorts. The weighting emphasizes firmware quality and data integration because these competencies are central to scalability and reliability in Industry 4.0-oriented IoT solutions.

Although the assessment criteria were identical across sections, the rubric was intentionally designed to capture differences in how students operationalized these competencies, rather than their mere exposure to them.

3.3.2. Survey Validation

The perception instrument comprised 12 items adapted from the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) to capture students’ perceived competence and interest/enjoyment throughout the PBL intervention. Prior to full deployment, the questionnaire was piloted with an independent group of students (

) to verify clarity and internal consistency. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding

, which indicates good internal consistency for the intended constructs. Descriptive summaries of the survey responses are reported in

Section 4, while inferential comparisons across cohorts are presented separately in

Section 4.2.

4. Results

This section presents both aggregated and cohort-specific empirical findings derived from the structured survey (), rubric-based evaluations, and classroom observations. Internal consistency of the survey instrument was verified (Cronbach’s ).

4.1. Progression of Perceived Learning (RQ1)

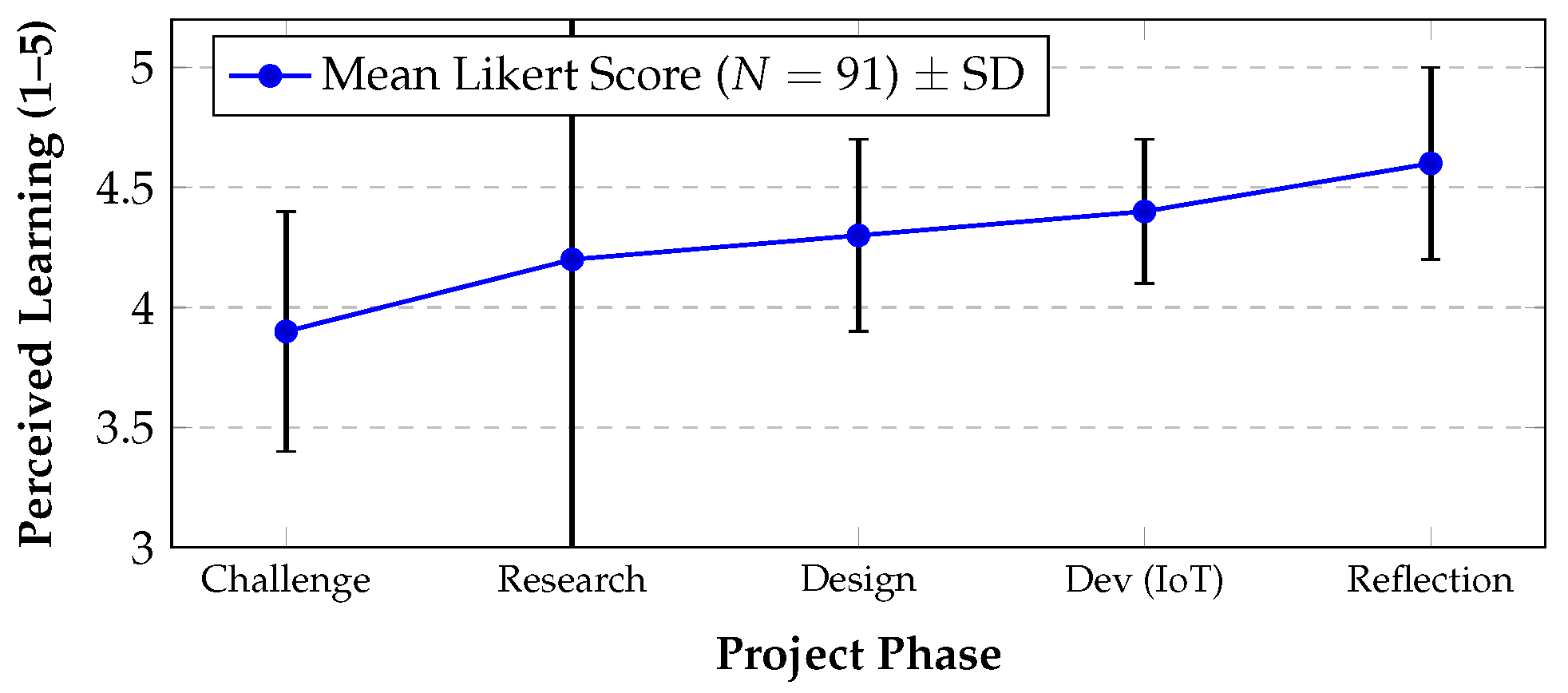

Students rated their perceived learning at the conclusion of each PBL phase. As hypothesized (

), the integration of the IoT architecture resulted in a sustained increase in perceived competence [

44].

Figure 5 illustrates this trajectory, showing a peak during the “Development” (

) and “Reflection” (

) phases, consistent with findings by [

15].

In addition to descriptive trends, inferential tests were conducted to evaluate whether observed differences across course sections (NRC-33561/33562/33563) were statistically supported (

Section 4.2).

4.2. Inferential Statistical Analysis

To complement the descriptive findings, inferential statistical tests were conducted to assess whether the observed differences across course sections (NRC-33561, NRC-33562, and NRC-33563) were statistically supported. Depending on distributional assumptions, one-way ANOVA or the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to rubric-derived scores and survey outcomes. When omnibus tests reached significance, post hoc comparisons were performed (Tukey HSD for ANOVA; Dunn’s test with Holm correction for Kruskal–Wallis). Effect sizes were estimated using or , respectively, with a significance threshold of . Normality assumptions were evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test together with visual inspection of Q–Q plots, while homoscedasticity was assessed using Levene’s test. When these assumptions were violated, the Kruskal–Wallis test was selected as a non-parametric alternative.

As summarized in

Table 3, statistically significant differences were observed across cohorts for key technical dimensions, particularly firmware quality and data integration. In contrast, overall course recommendation rates showed weaker or non-significant differences between sections. These results provide inferential support for the discipline-specific performance patterns identified in the descriptive analysis.

4.3. Dashboards as Cognitive Artefacts (RQ2)

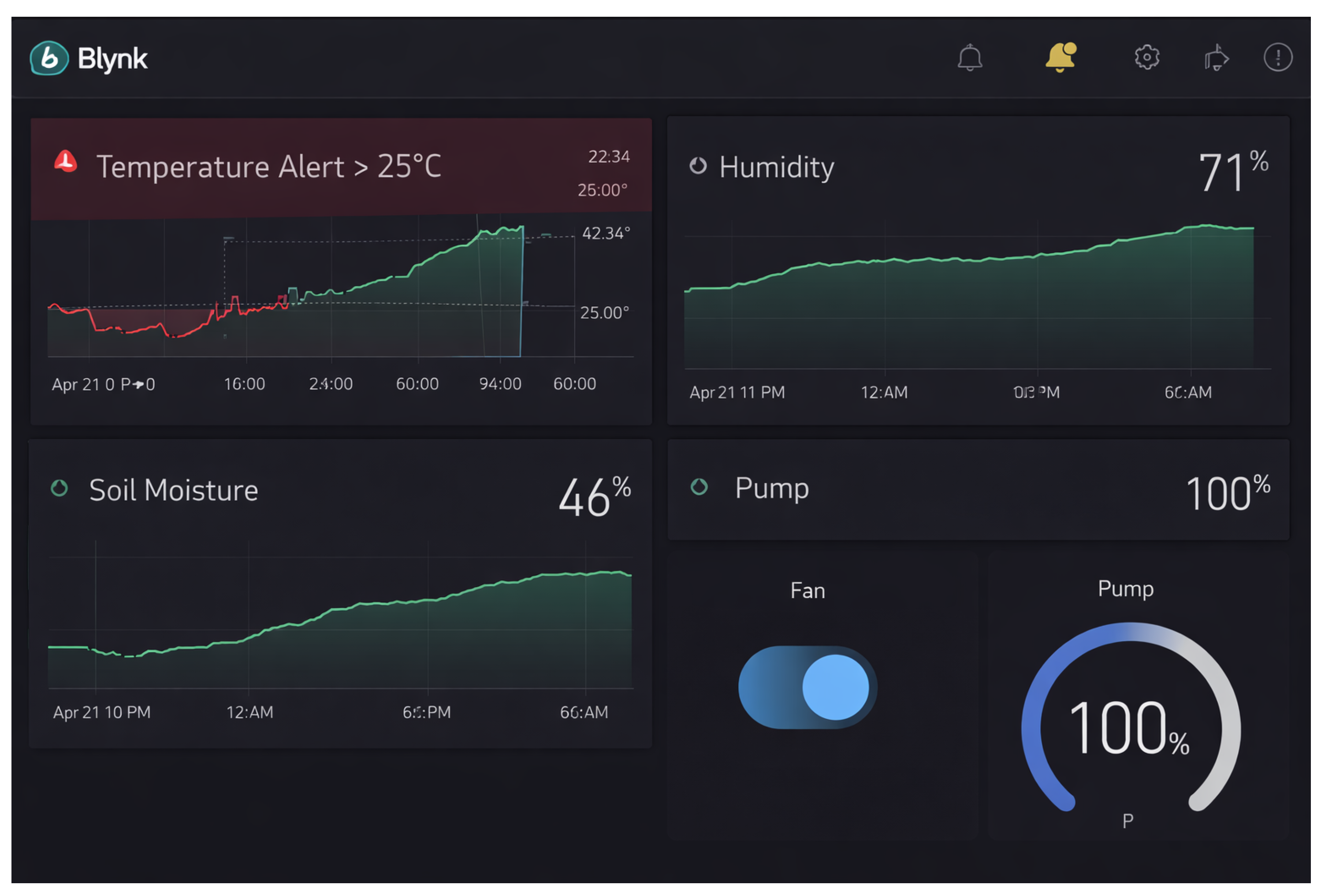

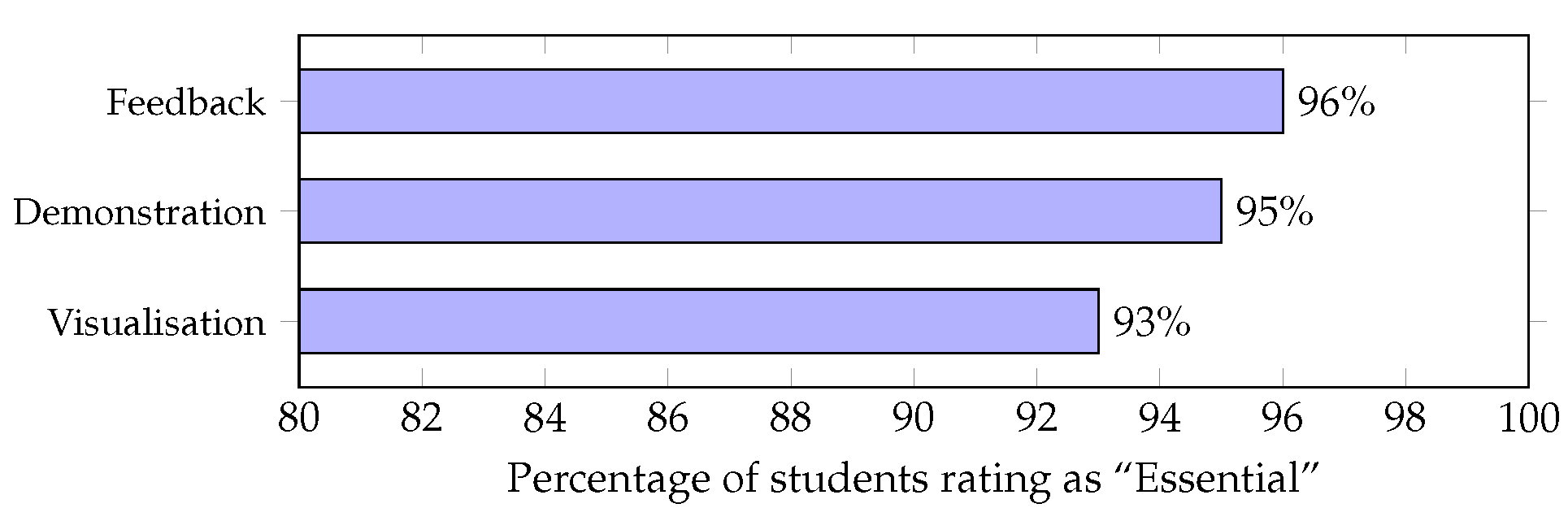

Figure 6 illustrates a representative cloud-based dashboard configuration employed by student teams across all cohorts during the validation phase. The dashboard acted as a cognitive artefact rather than a passive visualization tool, supporting the interpretation of time-series data, the identification of threshold conditions, and the implementation of logic-based decisions related to system actuation.

Because the use of dashboards as communication and reasoning tools was consistent across all cohorts,

Figure 7 reports aggregated results. Group-specific differences related to technical implementation are instead analyze in

Section 4.2 and in the subsequent error pattern analysis.

4.4. Competency Development (RQ3)

The intervention fostered transversal competencies, as detailed in

Table 4. The high scores in “Scientific Reasoning” (

) suggest that the shared IoT architecture fostered necessary interdependence, a key factor in collaborative engineering education [

45,

46].

4.5. Disciplinary Divergence in Technical Failures

Beyond the self-reported metrics, an analysis of the final source code submissions revealed distinct failure patterns correlated with the students’ disciplinary backgrounds. This “error analysis” provides critical insights for curricular adaptation.

Industrial Engineering Cohort (NRC-33563): The most frequent technical deficit in this group was the misuse of blocking functions. Approximately 65% of the code submissions relied heavily on delay() functions, which compromised the ESP32’s ability to multitask (e.g., reading sensors while maintaining Wi-Fi connection). This aligns with their disciplinary focus on linear process flows rather than concurrent event handling. However, this group excelled in the Application Layer, designing the most intuitive and business-logic-oriented dashboards (e.g., calculating projected crop yield based on humidity data).

Environmental Engineering Cohort (NRC-33561): This cohort demonstrated superior performance in the Physical Layer. Their calibration of soil moisture sensors and DHT11 modules was significantly more rigorous compared to other groups, often implementing hardware-based noise filtering (capacitors). Conversely, they struggled with the Network Layer, specifically with JSON serialization for data transmission, viewing the cloud connectivity as a “black box” obstacle rather than a networking component.

Electrical/Mixed Cohort (NRC-33562): As expected, this group produced the most electrically robust prototypes, with near-zero incidents of short circuits or voltage drops. However, their focus was often overly narrow on the “device” rather than the “system.” While their firmware was efficient, their cloud dashboards were often rudimentary, displaying raw data values without context or actionable thresholds, highlighting a gap in data analytics competencies.

5. Discussion

The results support the hypothesis (

) that integrating full-stack IoT architectures into Project-Based Learning enhances the development of scientific and technical competencies. These findings are consistent with prior work on the educational value of microcontrollers in physics education [

47], while extending this evidence to a multidisciplinary engineering context.

5.1. From Syntax Debugging to System Debugging

The development phase represented a clear cognitive turning point for students. Unlike isolated simulations, the open-ended nature of the implemented IoT architecture required learners to distinguish between sensor noise, network latency, and environmental variation [

48]. This shift reflects a transition from localized syntax debugging toward system-level reasoning, where faults emerge from interactions between hardware, firmware, and network components [

49].

5.2. Dashboards as Human–Computer Interfaces (HCI) for Reasoning

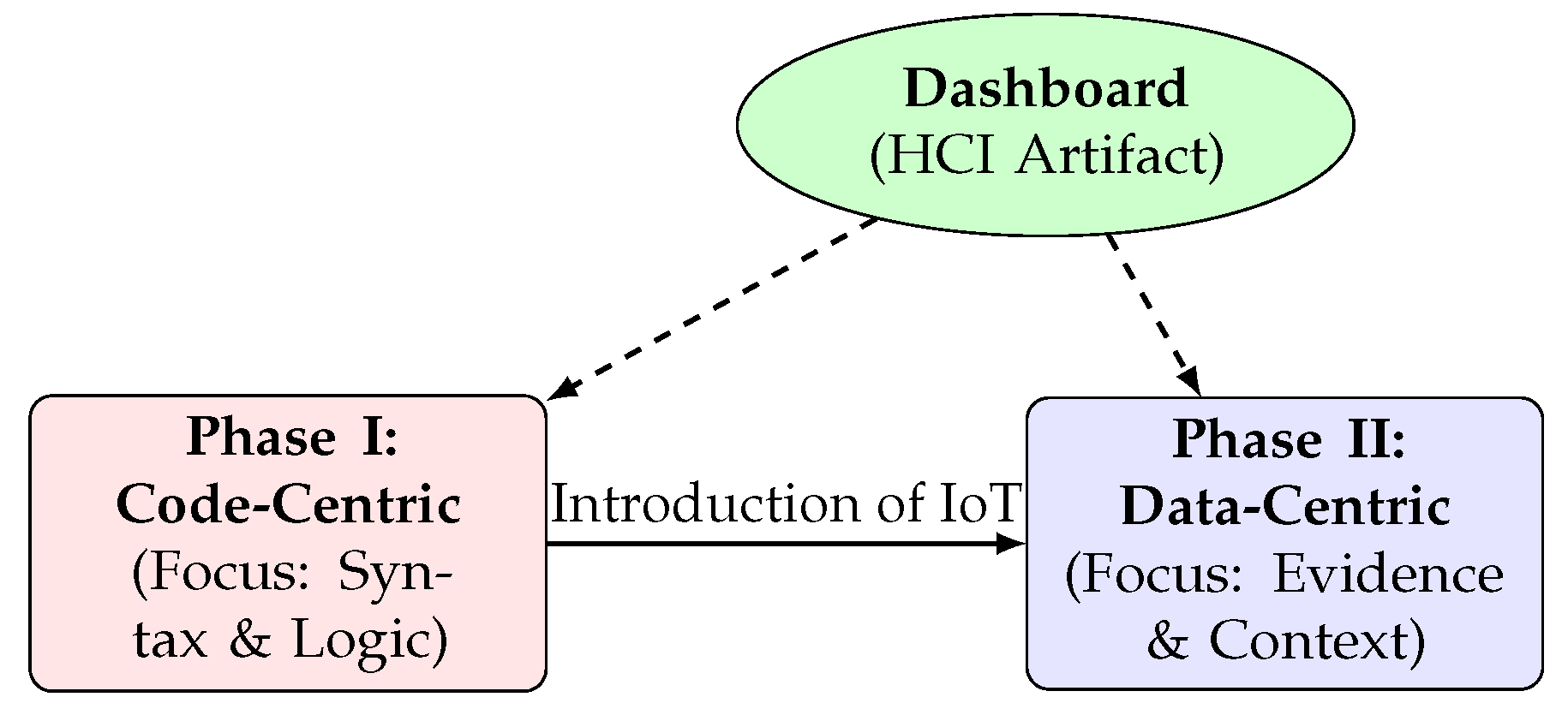

One of the central findings related to RQ2 concerns the role of dashboards as shared cognitive artefacts within the learning process. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the introduction of real-time data visualization progressively redirected students’ attention from a predominantly code-centric perspective—focused on syntax correctness and isolated logic—to a data-centric mode of reasoning grounded in contextual interpretation and evidence-based decision making.

Rather than acting as passive visualization tools, dashboards functioned as mediating Human–Computer Interfaces (HCI) that shaped how students framed problems, interpreted system behavior, and iteratively refined their solutions. This form of technological mediation aligns with core Industry 4.0 competencies by fostering analytical reasoning, situational awareness, and decision making supported by continuous data streams [

50].

5.3. Generalizability and Contextual Limitations

The findings should be interpreted within the institutional and regional context of the study. The intervention was conducted at a single university in the Peruvian Andes, and projects were explicitly aligned with local agricultural and apicultural challenges. These contextual factors may influence student motivation and perceptions of technological relevance.

Despite this specificity, the underlying pedagogical principles—namely the use of low-cost open-source hardware, full-stack IoT architectures, and Project-Based Learning—are transferable to other engineering programs operating in comparable socio-economic environments. Further multi-institutional studies are required to assess the robustness of the proposed framework across diverse educational settings.

5.4. Comparison with Related Work

Table 5 situates the present study within recent IoT-focused educational interventions. While prior work has emphasized introductory programming or isolated platform use [

4,

51], the current study integrates the complete sensing-to-cloud pipeline to support scientific reasoning and data-driven argumentation.

Taken together, these contrasts suggest that the main contribution of the present work lies in combining low-cost full-stack IoT prototyping with comparative evidence across engineering disciplines under a unified PBL design.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the design, implementation, and evaluation of a full-stack IoT architecture aimed at fostering computing competencies in undergraduate engineering students enrolled primarily in the second and third years of their programs. The results demonstrate that transitioning from local, offline coding exercises to sensing-to-cloud workflows significantly enhances students’ ability to interpret and reason with data.

The adoption of a complete IoT stack functioned not only as a technical solution but also as a cognitive scaffold. It encouraged students to engage with the systemic characteristics of Industry 4.0, shifting their focus from isolated execution errors toward broader considerations of system performance, latency, and data integrity.

Cloud-based dashboards emerged as a central Human–Computer Interface for scientific reasoning. These visualization tools acted as cognitive artefacts that supported a transition from intuitive assumptions to evidence-based argumentation grounded in time-series data. This confirms the role of real-time telemetry in bridging abstract programming logic with physical environmental processes.

Finally, the findings demonstrate that low-cost open-source hardware such as the ESP32 can replicate key functionalities of industrial monitoring systems in an educational context. This supports a scalable and accessible model for engineering education, particularly in regions where access to high-end infrastructure remains limited. Future work will explore the integration of Edge AI techniques (e.g., TinyML) and extend the study to multiple institutions to further assess the generalizability of the proposed framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.G. and C.V.-S.; methodology, C.V.-S.; software, M.T.-Y.; validation, V.G., M.T.-Y. and C.V.-S.; formal analysis, C.V.-S.; investigation, V.G. and M.T.-Y.; resources, V.G.; data curation, M.T.-Y.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V.-S.; writing—review and editing, V.G., M.T.-Y. and C.V.-S.; visualization, C.V.-S.; supervision, C.V.-S.; project administration, V.G. and C.V.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution; Currency: Surry Hills, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jaroodi, J.; Mohamed, N.; Abukhousa, E. Health 4.0: On the Way to Realizing the Healthcare of the Future. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 211189–211210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, Z.; Guan, Y. AI-Driven Intelligent Data Analytics and Predictive Analysis in Industry 4.0: Transforming Knowledge, Innovation, and Efficiency. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 864–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupac-Yupanqui, M.; Vidal-Silva, C.; Pavesi-Farriol, L.; Sánchez Ortiz, A.; Cárdenas-Cobo, J.; Pereira, F. Exploiting Arduino Features to Develop Programming Competencies. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 20602–20615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, B.A.; Garay, L.I.; Ruiz, E.F. Implementación del aprendizaje basado en proyectos como herramienta en asignaturas de ingeniería aplicada. RIDE Rev. Iberoam. Investig. Desarro. Educ. 2018, 9, 20–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Zhang, G.; Meqdad, M.N.; Chen, S. A systematic and comprehensive review and investigation of intelligent IoT-based healthcare systems in rural societies and governments. Artif. Intell. Med. 2023, 146, 102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, I.; Calderon, A. Challenges in the Teaching of Industry 4.0 to Non-IT Engineering Students. Comput. Educ. 2022, 186, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Silva, C.; Guevara, V.; Tupac-Yupanqui, M. Enhancing Computational Thinking in Higher Education through Interaction with Real-Time Data. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sütőová, A.; Vykydal, D.; Vargova, S.; Palacka, R.; Kočiško, R. Competence gap analysis of early-career Quality Engineers in the field of Quality 4.0. TQM J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.; Azevedo, M.L.d.R.; Godinho Filho, M.; Ganga, G.M.D.; Lizarelli, F.L. Industry 4.0 Skills in Industrial Engineering Courses: Contributing to the Role of Universities Toward Sustainable Development. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 8369–8387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terroso, T.; Pinto, M. Programming for Non-Programmers: An Approach Using Creative Coding in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the Third International Computer Programming Education Conference (ICPEC 2022), Open Access Series in Informatics (OASIcs); Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik: Dagstuhl, Germany, 2022; Volume 102, pp. 13:1–13:8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez de Dampierre, M.; Gaya-López, M.C.; Lara-Bercial, P.J. Evaluation of the Implementation of Project-Based-Learning in Engineering Programs: A Review of the Literature. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmos, A.; Fink, F.K.; Krogh, L. (Eds.) The Aalborg PBL Model: Progress, Diversity and Challenges; Aalborg University Press: Aalborg, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lavado-Anguera, S.; Velasco-Quintana, P.J.; Terrón-López, M.J. Project-Based Learning (PBL) as an Experiential Pedagogical Methodology in Engineering Education: A Review of the Literature. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abichandani, P.; Sivakumar, V.; Lobo, D.; Iaboni, C.; Shekhar, P. Internet-of-Things Curriculum, Pedagogy, and Assessment for STEM Education: A Review of Literature. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 38351–38369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozcu Cakir, N.; Guven, G. Enhancing engineering design, scientific creativity, and decision-making skills in prospective science teachers through engineering design-based robotics coding applications. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumina, S.; Patten, K.; Gerdes, J. The evolution of IoT education within an IT curriculum. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 6723–6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.K. Reflexive Praxis in Curriculum Transformation: The Case of Engineering Education in the Global South. In North American and European Perspectives on Sustainability in Higher Education; Leal Filho, W., Newman, J., Lange Salvia, A., Viera Trevisan, L., Corazza, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Mieles, J.; Tupac-Yupanqui, M.; Mari-Loardo, S.; Vidal-Silva, C. Integrating ESP32-Based IoT Architectures and Cloud Visualization to Foster Data Literacy in Early Engineering Education. Computers 2026, 15, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.; Sharp, T. Comparative Analysis of ESP32 and Arduino for IoT Education. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 112234–112245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercog, D.; Lerher, T.; Truntič, M.; Težak, O. Design and Implementation of ESP32-Based IoT Devices. Sensors 2023, 23, 6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, J.C.K.; Verhulsdonck, G. Smart Education in Smart Cities: Layered Implications for Networked and Ubiquitous Learning. IEEE Trans. Technol. Soc. 2023, 4, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirzado, F.A.; Ahmed, A.; Hussain, S.; Ibarra-Vázquez, G.; Terashima-Marin, H. Assessing Computational Thinking in Engineering and Computer Science Students: A Multi-Method Approach. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danieli, P.P.; Addeo, N.F.; Lazzari, F.; Manganello, F.; Bovera, F. Precision Beekeeping Systems: State of the Art, Pros and Cons, and Their Application as Tools for Advancing the Beekeeping Sector. Animals 2024, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowla, M.N.; Mowla, N.; Shah, A.F.M.S.; Rabie, K.M.; Shongwe, T. Internet of Things and Wireless Sensor Networks for Smart Agriculture Applications: A Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 145813–145852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Al-Rizzo, H. Enhancing Student Engagement in IoT Courses through Real-World Case Studies. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnawar, S.T. A Comprehensive Review on PBL and Digital PBL in Engineering Education: Status, Challenges and Future Prospects. J. Eng. Educ. Transform. 2025, 37, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmqvist, J.; Lundqvist, U.; Rosén, A.; Edström, K. The CDIO Syllabus 3.0: An Updated Statement of Goals. In Proceedings of the 18th International CDIO Conference, Reykjavik, Iceland, 13–15 June 2022; Reykjavik University: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2022. Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-316352 (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Zhang, L.; Ma, Y. A study of the impact of project-based learning on student learning effects: A meta-analysis study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1202728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potharalanka, L. Low-Code Platforms in Public Education: Opportunities and Challenges for Equitable Access. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2025, 7, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystakidis, S. Deep Meaningful Learning in IoT Education. Sensors 2021, 21, 4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodali, R.K.; Soratkal, S. MQTT based home automation system using ESP8266. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Region 10 Humanitarian Technology Conference (R10-HTC); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzis, D.; Angelopoulos, J. Design and Development of an IoT-based Monitoring System for Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2021, 96, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah, A.; Ghani, A.; Daud, A.; Jalal, A.; Bilal, M.; Crowcroft, J. Towards Smart Education through Internet of Things: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisnapati, P.; Wardana, I. ESP32-based Smart Garden System with IoT for Education. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2450, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, M.; Ginzburg, T.; Erduran, S. Nature of Engineering. Sci. Educ. 2024, 33, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño-Elizondo, B.L.; García-Reyes, H. What does Industry 4.0 mean to Industrial Engineering Education? Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 217, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, P.; Ruiz, L. IoT in Environmental Engineering: A Project-Based Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapriyan, R.; Raj, L.; Selvi, T.; Raj, G. Literature Review on Augmented Reality in Electrical Engineering Education. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference for Innovation in Technology (INOCON); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkonis, P.; Giannopoulos, A.; Trakadas, P.; Masip-Bruin, X.; D’Andria, F. A Survey on IoT-Edge-Cloud Continuum Systems: Status, Challenges, Use Cases, and Open Issues. Future Internet 2023, 15, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariah, T.; Klugman, N.; Dutta, P. ThingSpeak in the Wild: Exploring 38K Visualizations of IoT Data. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems (SenSys ’22); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plauska, I.; Liutkevičius, A.; Janavičiūtė, A. Performance Evaluation of C/C++, MicroPython, Rust and TinyGo Programming Languages on ESP32 Microcontroller. Electronics 2023, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, R.; Jahromi, H.D.; Sedaghat, S. Design and Implementation of a Near Real-Time Human Detection Robot Using YOLO Framework and IoT Technologies. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 175960–175983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, S.; Diaz, A. Measuring Student Satisfaction in IoT Courses: A Structural Equation Model. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Vidal-Silva, C.; Mancilla, G.; Tupac-Yupanqui, M.; Rubio, J. Sustainable e-Learning by Data Mining—Successful Results in a Chilean University. Sustainability 2023, 15, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Chan, C.K.Y. Evaluating technological interventions for developing teamwork competency in higher education: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2024, 83, 101382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherifi, T.; Salag, A.; Kerrouchi, S. Development of an Educational Low-Cost and ESP32-Based Platform for Fundamental Physics. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2023, 31, 1796–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilian, A.; Ahmed, K. From Soil to Software: Experience from a STEM Workshop on Smart Plant Care and Teachable Machines. In Proceedings of the SC ’25 Workshops of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis (SC Workshops ’25); Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troya, J.; Segura, S.; Burgueño, L.; Wimmer, M. Model Transformation Testing and Debugging: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coners, A.; Matthies, B.; Vollenberg, C.; Koch, J. Data Skills for Everyone! (?)–An Approach to Assessing the Integration of Data Literacy and Data Science Competencies in Higher Education. J. Stat. Data Sci. Educ. 2025, 33, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelke, S.A.; Kohen-Vacs, D.; Khomyakov, M.; Rosienkiewicz, M.; Helman, J.; Cholewa, M.; Molasy, M.; Górecka, A.; Gómez-González, J.-F.; Benis, A. Enhancing Lessons on the Internet of Things in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Medical Education with a Remote Lab. Sensors 2024, 24, 6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The four-stage Project-Based Learning (PBL) methodological framework implemented during the semester.

Figure 1.

The four-stage Project-Based Learning (PBL) methodological framework implemented during the semester.

Figure 2.

Classroom setting during the Project-Based Learning intervention. The image illustrates student teams collaboratively engaging with ESP32-based IoT kits, cloud-based monitoring dashboards, and instructor guidance within a regular teaching environment. The figure is provided for contextual and illustrative purposes and does not introduce additional quantitative data beyond those analyzed in the experimental results.

Figure 2.

Classroom setting during the Project-Based Learning intervention. The image illustrates student teams collaboratively engaging with ESP32-based IoT kits, cloud-based monitoring dashboards, and instructor guidance within a regular teaching environment. The figure is provided for contextual and illustrative purposes and does not introduce additional quantitative data beyond those analyzed in the experimental results.

Figure 3.

Sensing-to-cloud IoT architecture implemented in the PBL intervention. Solid arrows represent the operational data and control flow, including sensor data acquisition, firmware-based processing, wireless communication, cloud storage, dashboard visualization, and actuation commands. Dashed arrows indicate the pedagogical feedback loop, where insights derived from dashboard visualizations and stakeholder interpretation inform iterative redesign and firmware adjustments.

Figure 3.

Sensing-to-cloud IoT architecture implemented in the PBL intervention. Solid arrows represent the operational data and control flow, including sensor data acquisition, firmware-based processing, wireless communication, cloud storage, dashboard visualization, and actuation commands. Dashed arrows indicate the pedagogical feedback loop, where insights derived from dashboard visualizations and stakeholder interpretation inform iterative redesign and firmware adjustments.

Figure 4.

Representative bench-top prototypes illustrating implementation diversity under the standardized ESP32 sensing-to-cloud kit (sensor and actuator configurations vary by project context).

Figure 4.

Representative bench-top prototypes illustrating implementation diversity under the standardized ESP32 sensing-to-cloud kit (sensor and actuator configurations vary by project context).

Figure 5.

Evolution of student perceived learning across the PBL lifecycle. Error bars represent Standard Deviation.

Figure 5.

Evolution of student perceived learning across the PBL lifecycle. Error bars represent Standard Deviation.

Figure 6.

Representative cloud dashboard used during the intervention to support data interpretation and decision-making. Line charts display real-time environmental variables, where color coding differentiates sensor states and threshold conditions (e.g., normal operation versus alert-triggering values). Numeric indicators summarize current readings, while toggle and gauge elements visualize actuator states such as pump and fan activation. The figure is provided for illustrative purposes and does not introduce additional quantitative results beyond those analyzed in the study.

Figure 6.

Representative cloud dashboard used during the intervention to support data interpretation and decision-making. Line charts display real-time environmental variables, where color coding differentiates sensor states and threshold conditions (e.g., normal operation versus alert-triggering values). Numeric indicators summarize current readings, while toggle and gauge elements visualize actuator states such as pump and fan activation. The figure is provided for illustrative purposes and does not introduce additional quantitative results beyond those analyzed in the study.

Figure 7.

Student valuation of communication artefacts.

Figure 7.

Student valuation of communication artefacts.

Figure 8.

Cognitive shift enabled by the full-stack IoT architecture. Solid arrows indicate the transition between instructional phases, from a code-centric focus to a data-centric reasoning approach following the introduction of IoT technologies. Dashed arrows represent the mediating role of the dashboard as an HCI artefact, influencing students’ cognitive processes across both phases by supporting reflection, interpretation, and iterative reasoning based on real-time data.

Figure 8.

Cognitive shift enabled by the full-stack IoT architecture. Solid arrows indicate the transition between instructional phases, from a code-centric focus to a data-centric reasoning approach following the introduction of IoT technologies. Dashed arrows represent the mediating role of the dashboard as an HCI artefact, influencing students’ cognitive processes across both phases by supporting reflection, interpretation, and iterative reasoning based on real-time data.

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of participants by course section (NRC).

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of participants by course section (NRC).

| Group | NRC | Dominant Discipline | Male | Female | Total |

|---|

| A | 33561 | Environmental Eng. | 18 | 12 | 30 |

| B | 33562 | Electrical/Mixed | 24 | 8 | 32 |

| C | 33563 | Industrial Eng. | 26 | 7 | 33 |

Table 2.

Technical Assessment Rubric used to evaluate the IoT Prototypes (Max Score: 20).

Table 2.

Technical Assessment Rubric used to evaluate the IoT Prototypes (Max Score: 20).

| Dimension | Criteria Description | Weight |

|---|

| Hardware Robustness (30%) | The circuit is physically stable, using proper pull-up/pull-down resistors. Sensor readings are consistent (no floating pins). The ESP32 is powered correctly (separation of power rails for relays). | 6 pts |

| Firmware Quality (40%) | Code is modularized into functions (voids). Avoidance of delay() in favour of millis() for non-blocking operations. Correct handling of Wi-Fi reconnection events. Use of libraries is efficient and commented. | 8 pts |

| Data Integration (30%) | Successful transmission of telemetry to the cloud (ThingSpeak/Blynk). Dashboard displays real-time data with appropriate units. Implementation of at least one logic-based alert (e.g., “If Temp > 30, turn on Fan”). | 6 pts |

Table 3.

Inferential comparison across cohorts supporting the descriptive findings.

Table 3.

Inferential comparison across cohorts supporting the descriptive findings.

| Outcome | Test | Statistical Result |

|---|

| Rubric total score (0–20) | ANOVA/Kruskal–Wallis | Significant differences detected () |

| Firmware quality subscore | ANOVA/Kruskal–Wallis | Significant differences detected () |

| Data integration subscore | ANOVA/Kruskal–Wallis | Significant differences detected () |

| Course recommendation (Yes/No) | test | No statistically significant differences |

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of self-reported competency development.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of self-reported competency development.

| Competency | Mean | SD | Observed Behavioural Indicator |

|---|

| Autonomy | 4.0 | 0.6 | Searching for datasheets independently. |

| Collaboration | 4.2 | 0.5 | Effective division of lobar. |

| Sci. Reasoning | 4.1 | 0.5 | Using graphs to explain anomalies. |

| Problem Solving | 4.1 | 0.5 | Diagnosing wiring errors via dashboards. |

Table 5.

Comparison with recent IoT-focused educational interventions.

Table 5.

Comparison with recent IoT-focused educational interventions.

| Study | Platform | Pedagogical Focus | Key Differentiator |

|---|

| [47] | ESP32 | Physics experiments | Uses microcontrollers to support inquiry activities; focuses on domain-specific experimentation. |

| [51] | IoT + cloud | Hybrid learning | Emphasizes cloud dashboards and remote interaction rather than full-stack prototyping. |

| [4] | Arduino | Introductory programming | Focuses on foundational coding skills; limited integration of full sensing-to-cloud workflows. |

| This study | ESP32 + cloud | PBL in multidisciplinary engineering | Integrates a complete sensing-to-cloud pipeline and uses dashboards as cognitive artefacts to support scientific reasoning and data-driven argumentation. |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |