Research Advances in Maize Crop Disease Detection Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

Foundational Definitions—ML (Machine Learning) and DL (Deep Learning)

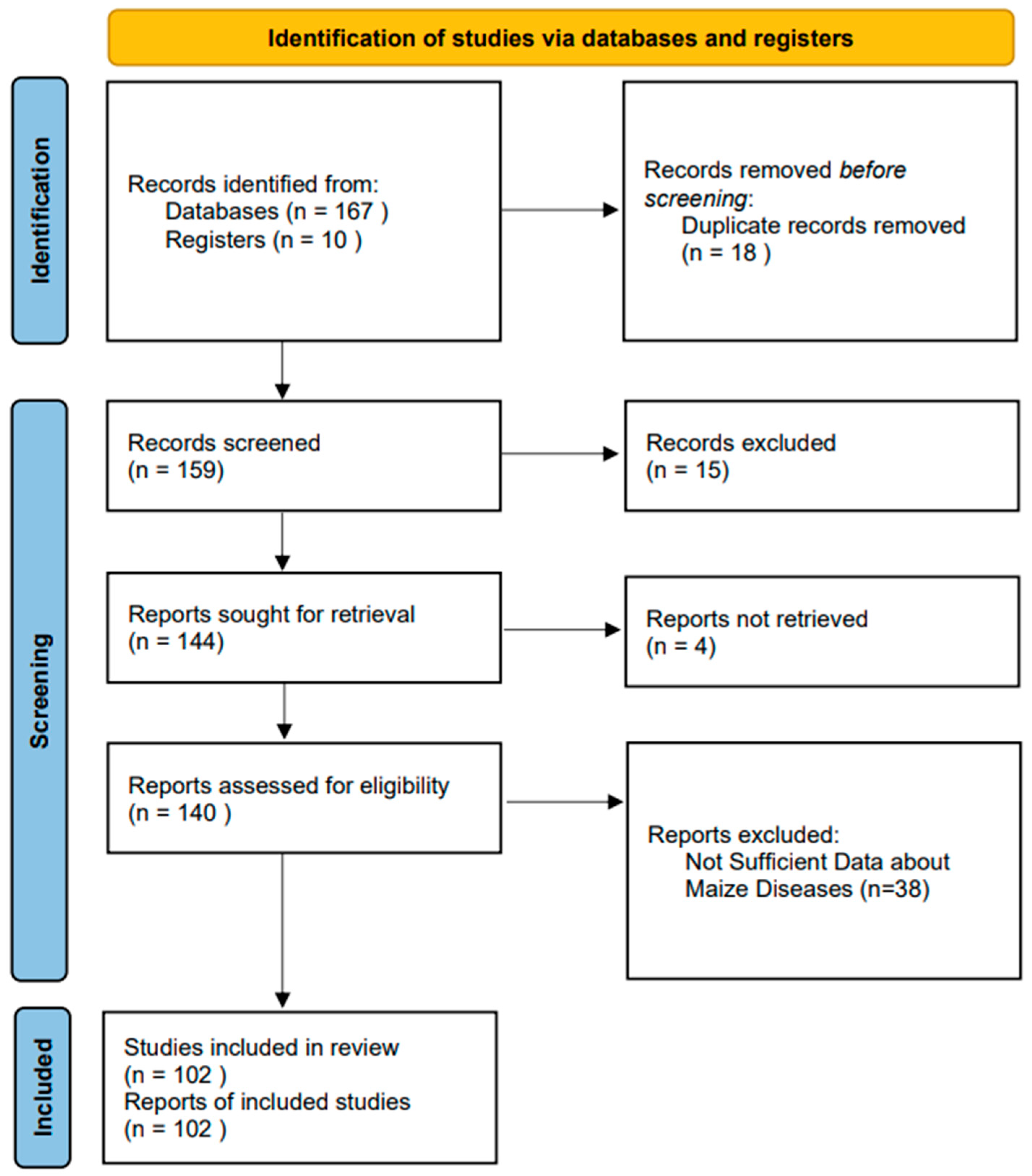

2. Research Methodology

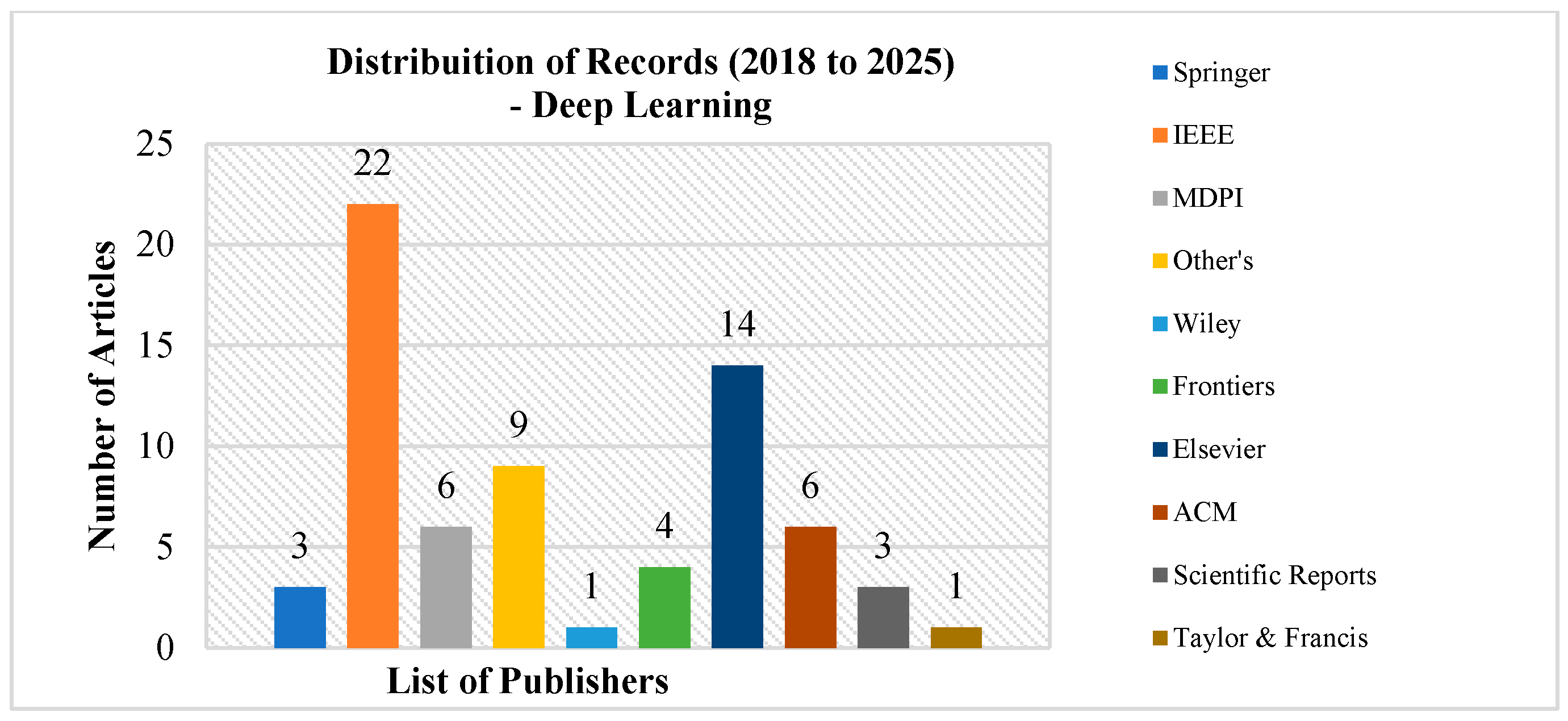

2.1. Risk of Bias and Evaluation of Study Quality

2.2. Examining Literature and Determining Eligibility

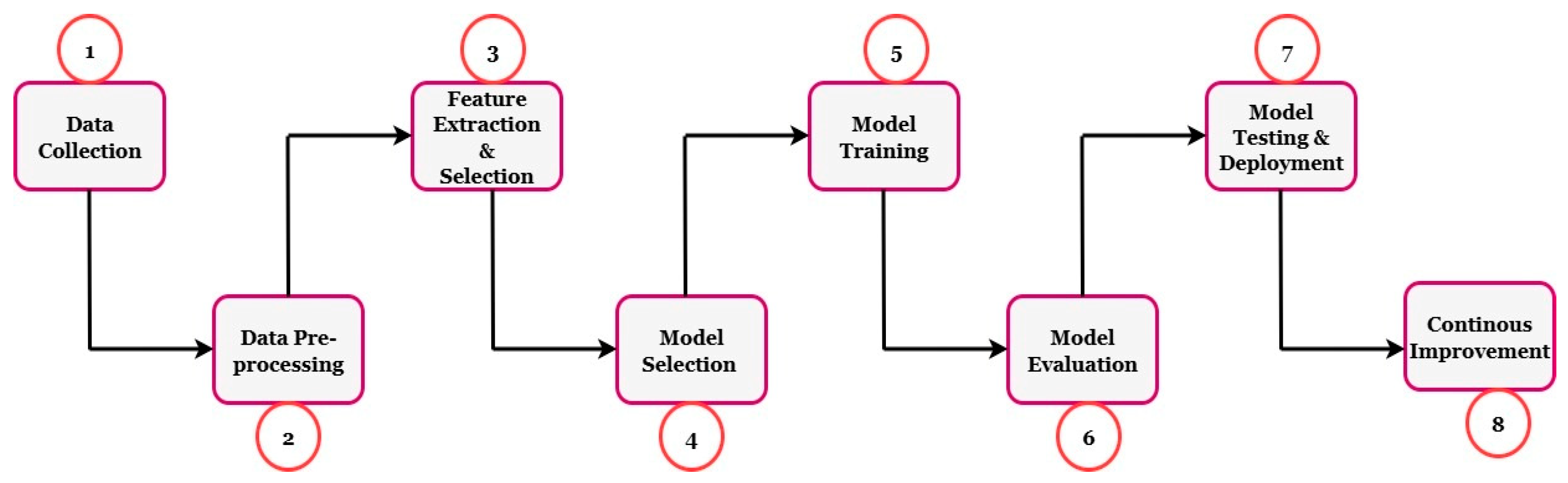

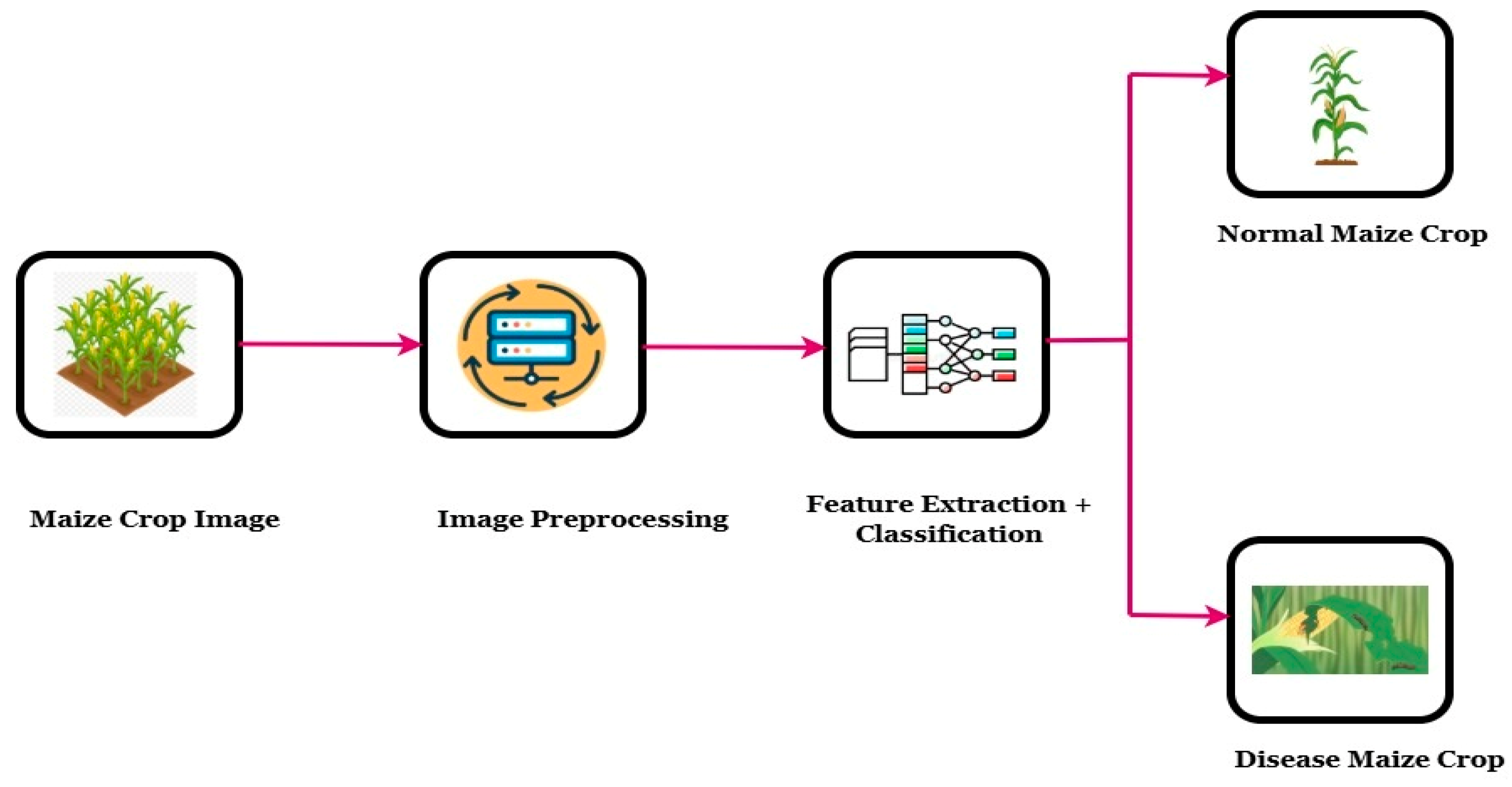

2.3. Conceptual Structure for DL and ML-Based Maize Disease Identification

2.4. Taxonomy of Learning Paradigms, Tasks, and Model Architectures for Maize Leaf Disease Detection

2.5. Scope and Limitations of the Review

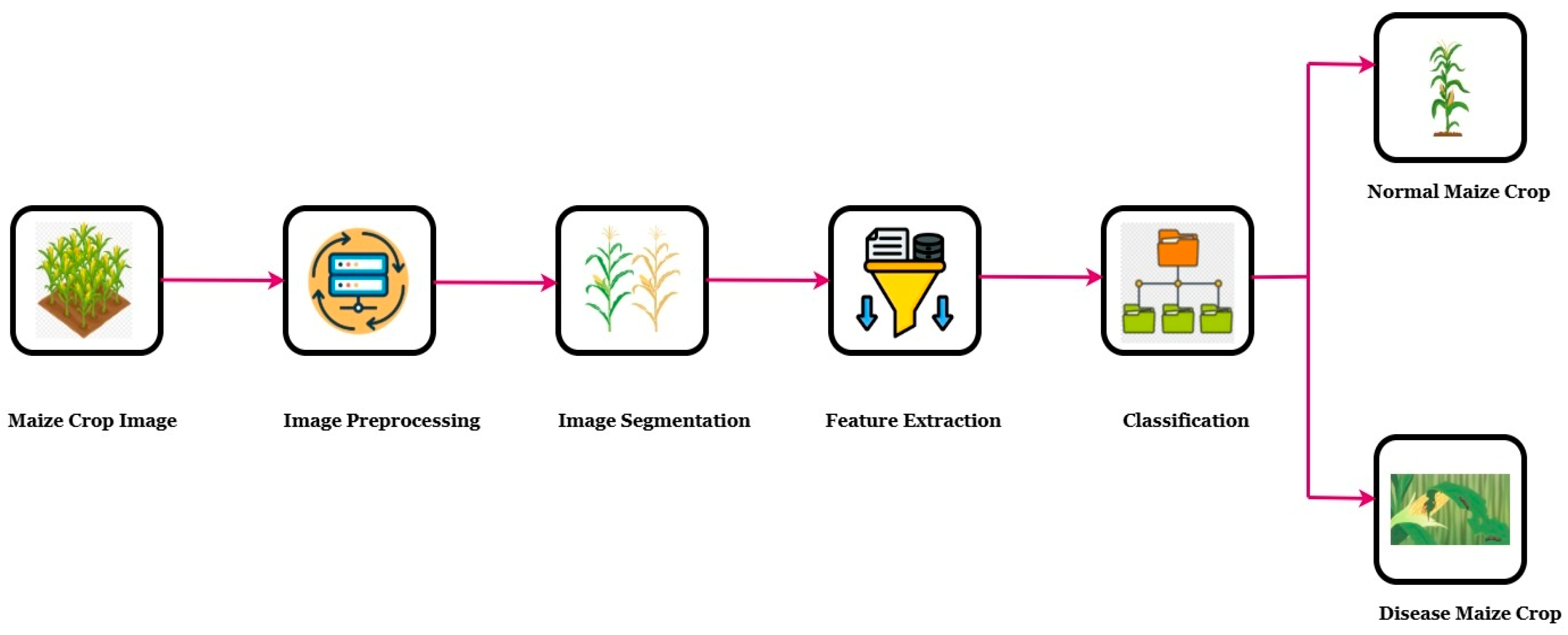

3. Maize Crop Disease Types and Datasets

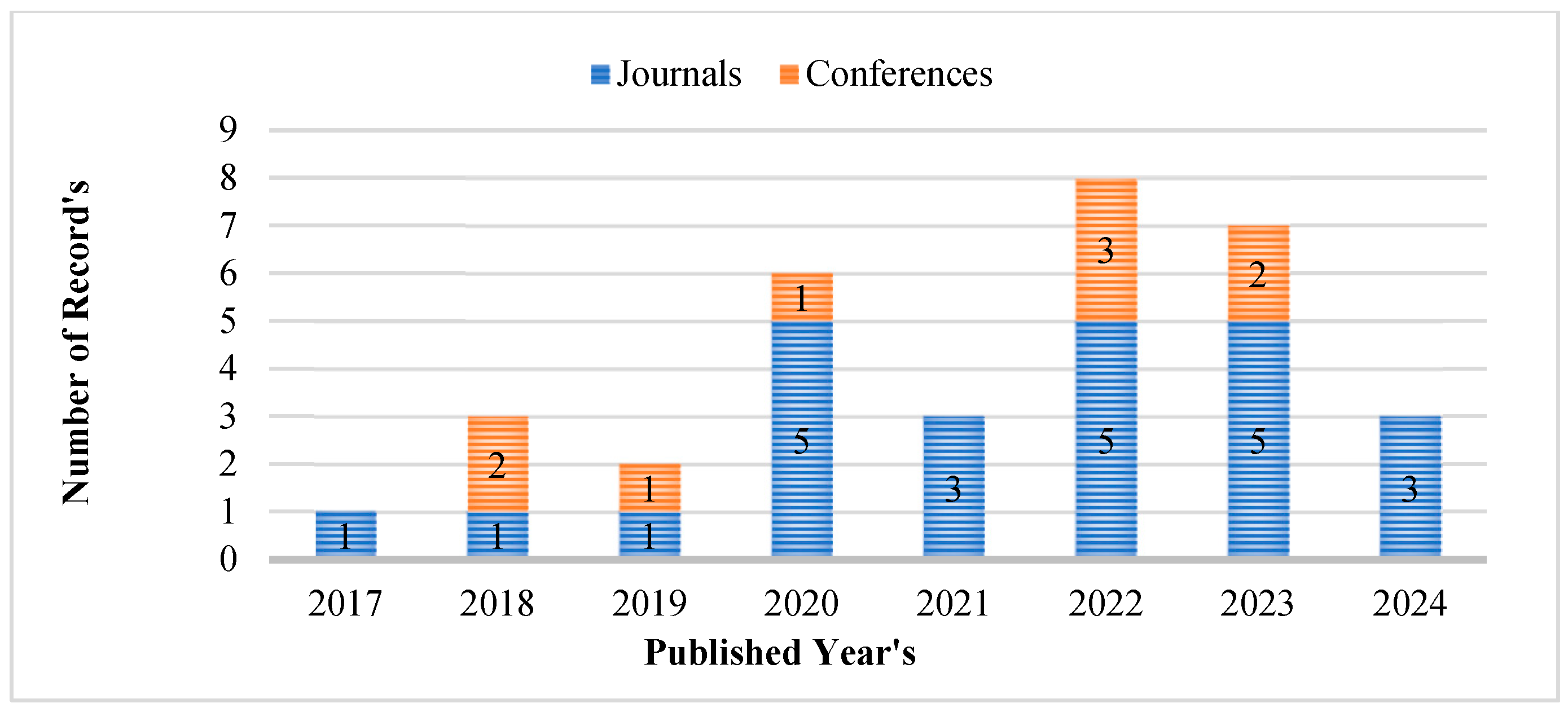

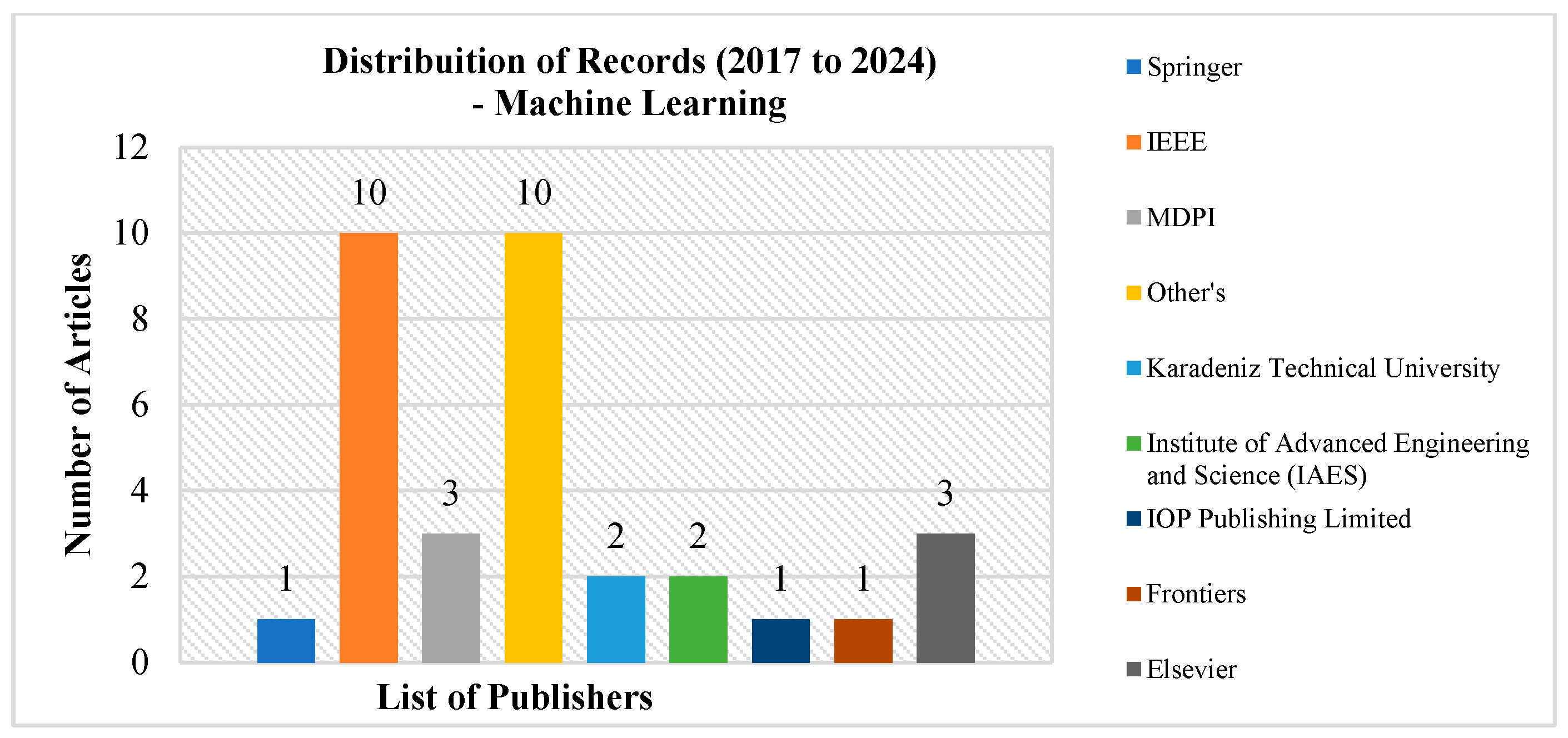

4. Machine Learning-Based Maize Crop Disease Detection

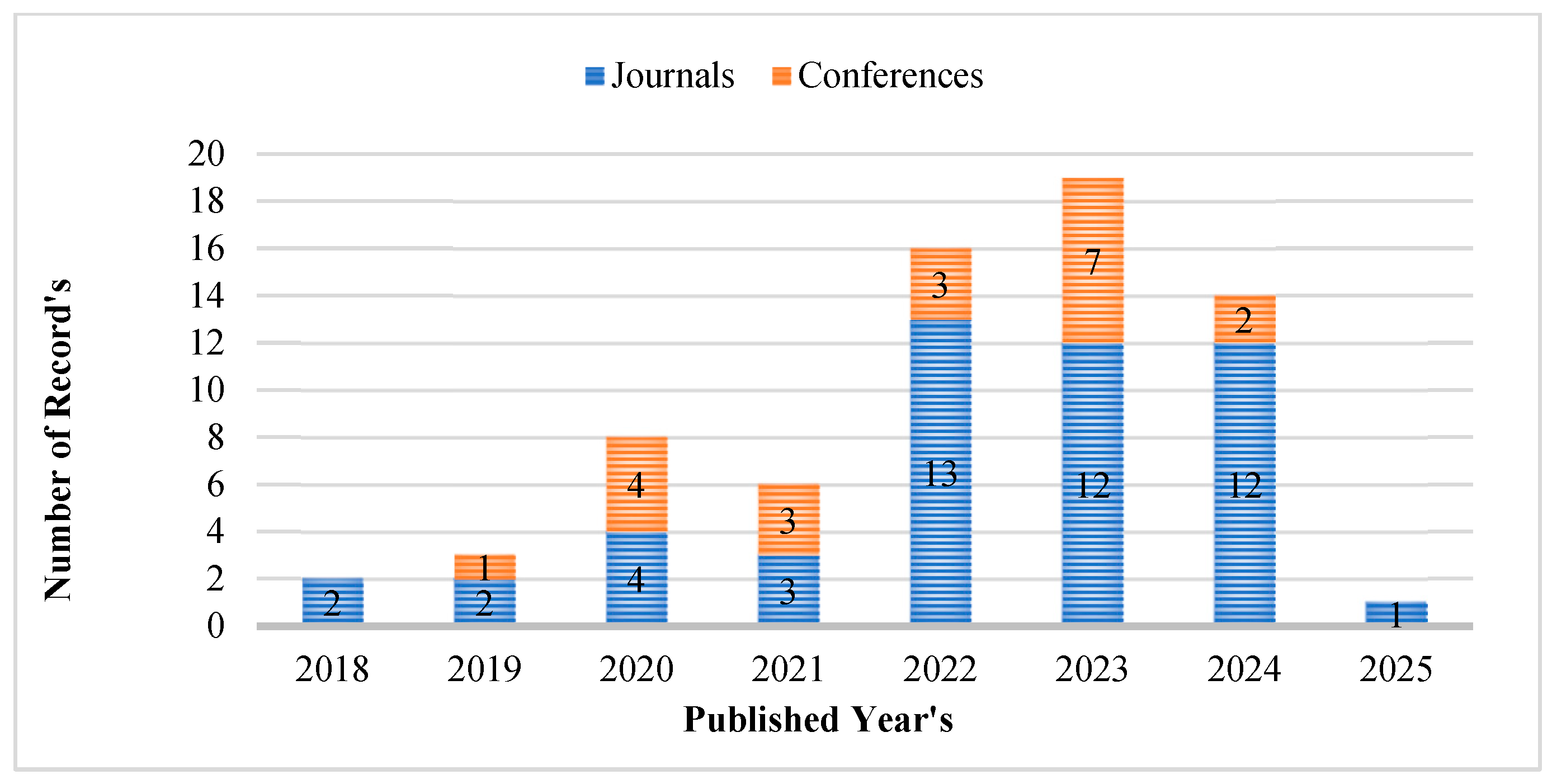

5. Deep Learning-Based Maize Crop Disease Detection

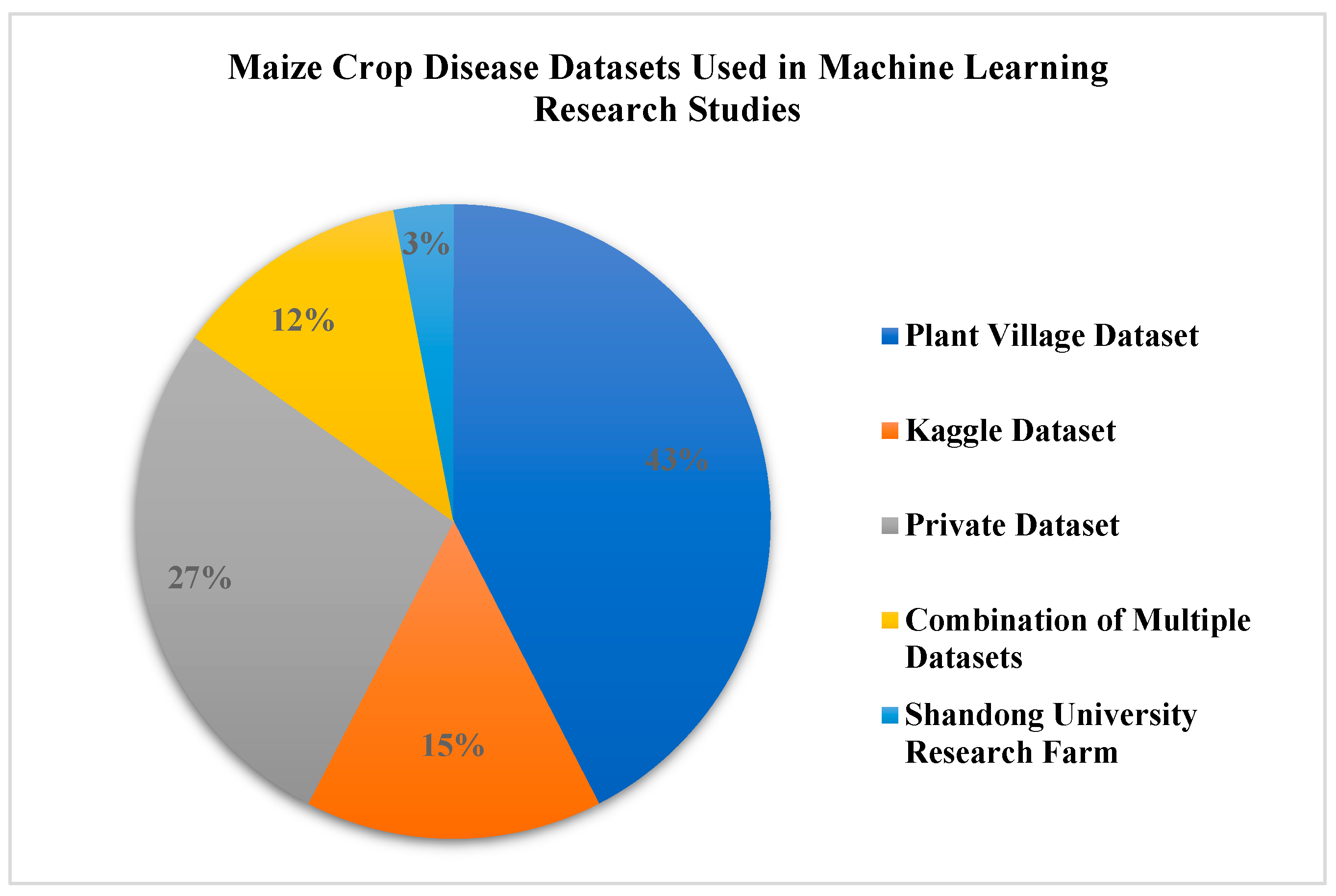

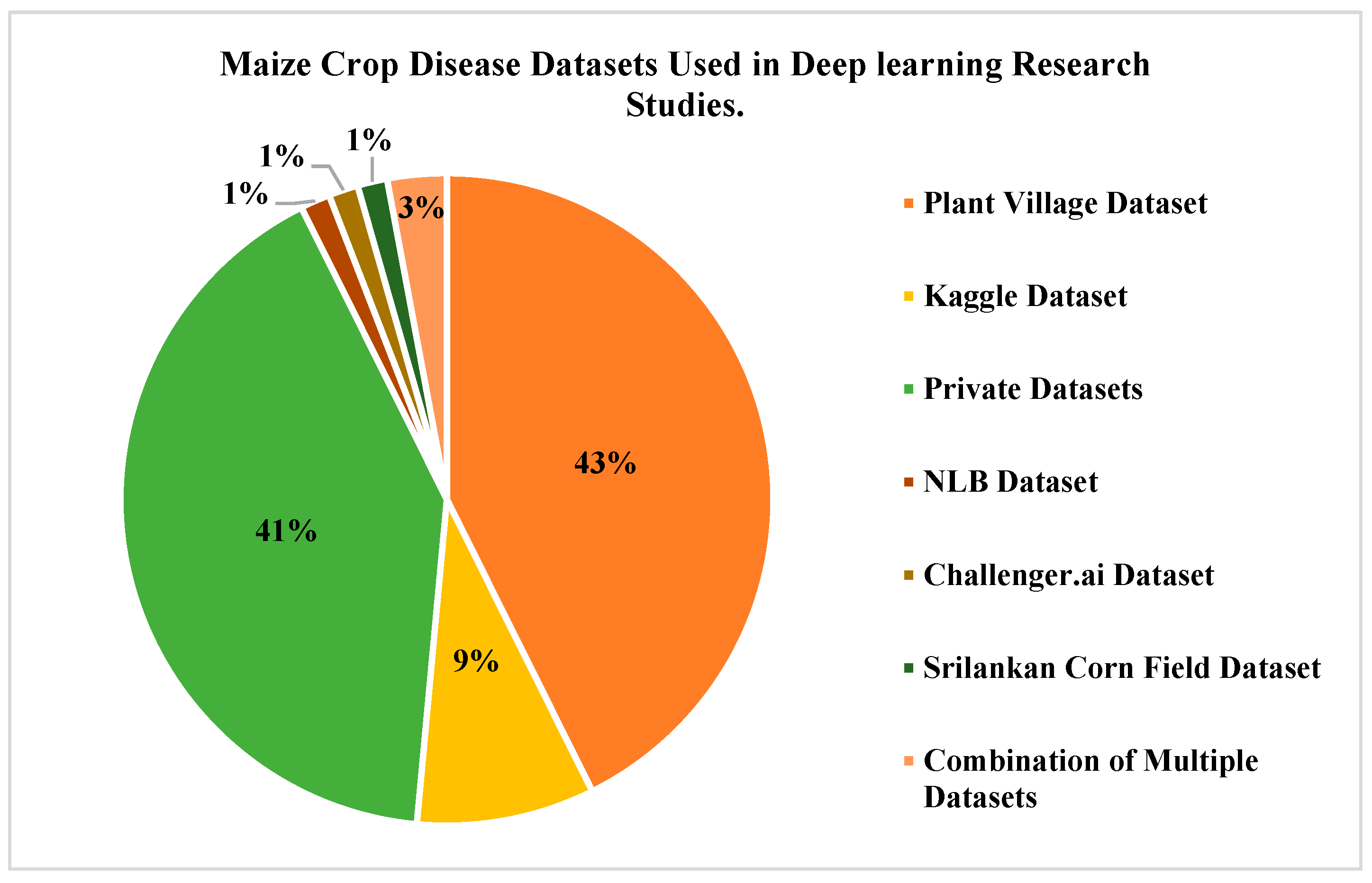

5.1. Research Findings—Datasets Focused

5.2. Research Findings—Diseases and DL Techniques Focused

6. Challenges in Using Maize Disease Detection Models in the Real World

6.1. Difficulties in Using Maize Disease Detection Systems in the Field

6.2. Limitations Impacting the Robustness of Real-World Models

6.3. Assessment Difficulties Caused by Class Imbalance

6.4. Study Region and Determined Restrictions

7. Discussion

7.1. Opportunities and Gaps in Multimodal Maize Disease Identification

7.2. Implications of Maize Disease Detection Systems for Ethics and Society

7.3. Quantitative Evaluation of Dependency on Datasets

7.4. Quantitative Evaluation of Metric Reporting Procedures

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Donatelli, M.; Magarey, R.D.; Bregaglio, S.; Willocquet, L.; Whish, J.P.; Savary, S. Modelling the impacts of pests and diseases on agricultural systems. Agric. Syst. 2017, 155, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruthi, U.; Nagaveni, V.; Raghavendra, B.K. A review on machine learning classification techniques for plant disease detection. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Advanced Computing & Communication Systems (ICACCS), Coimbatore, India, 15–16 March 2019; pp. 281–284. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Liu, W.; Feng, P.; Ye, T.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Z. Improving spatial disaggregation of crop yield by incorporating machine learning with multisource data: A case study of Chinese maize yield. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Gehman, K.; Yang, H.; Yang, Y. Prediction of the global occurrence of maize diseases and estimation of yield loss under climate change. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 5759–5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asibe, F.A.; Ngegba, P.M.; Mugehu, E.; Afolabi, C.G. Status and management strategies of major insect pests and fungal diseases of maize in Africa. A review. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2023, 19, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saquee, F.S.; Norman, P.E.; Saffa, M.D.; Kavhiza, N.J.; Pakina, E.; Zargar, M.; Diakite, S.; Stybayev, G.; Baitelenova, A.; Kipshakbayeva, G. Impact of different types of green manure on pests and disease incidence and severity as well as growth and yield parameters of maize. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Zhou, G.; He, M.; Chen, A.; Zhang, W.; Hu, Y. Maize leaf disease identification based on feature enhancement and DMS-robust AlexNet. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 57952–57966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilumbu, C.; Huang, Q.-X.; Sun, H.-M. Utilizing a DenseSwin Transformer Model for the Classification of Maize Plant Pathology in Early and Late Growth Stages. A Case Study of Its Utilization Among Zambian Farmers. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2024, 9, 1860–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Chen, S.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, B.; Li, A.; Cui, L.; Dai, R.; Zeng, Q. Tracking the impact of typhoons on maize growth and recovery using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data. A case study of Northeast China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 359, 110266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, L.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Luo, D.; Mu, J. A research review on deep learning combined with hyperspectral imaging in multiscale agricultural sensing. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 217, 108577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamparia, A.; Saini, G.; Gupta, D.; Khanna, A.; Tiwari, S.; de Albuquerque, V.H.C. Seasonal crop disease prediction and classification using a deep convolutional encoder network. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 39, 818–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Trivedi, V.; Sheth, V.; Shah, A.; Chauhan, U. ResTS. Residual deep interpretable architecture for plant disease detection. Inf. Process. Agric. 2022, 9, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshipour, A.; Jafari, A. Evaluation of support vector machine and artificial neural networks in weed detection using shape features. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 145, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, M.; Adil, K.; Rozina, C.; Saif, H.K.; Muhammad, S.M. Plant disease detection using deep learning. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2020, 9, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, S.A.; Harikrishnan, R. Comparison of Plant Leaf Classification Using Modified AlexNet and Support Vector Machine. Trait. Signal 2021, 38, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.S.; Khanna, P.; Sheorey, T.; Ojha, A. Trends in vision-based machine learning techniques for plant disease identification: A systematic review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 208, 118117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doutoum, A.S.; Tugrul, B. A review of leaf diseases detection and classification by deep learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 119219–119230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafik, W.; Tufail, A.; Namoun, A.; De Silva, L.C.; Apong, R.A.A.H.M. A systematic literature review on plant disease detection. Motivations, classification techniques, datasets, challenges, and future trends. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 59174–59203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Sarsaiya, S.; Wu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Shi, J. A review of plant leaf fungal diseases and their environmental speciation. Bioengineered 2019, 10, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Dong, B.; Zhu, B.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, J.; Song, K. A survey on deep learning-based object detection for crop monitoring: Pest, yield, weed, and growth applications: H. Lu et al. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 10069–10094 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, L.; Nagpal, J. A systematic review of recent machine learning techniques for plant disease identification and classification. IETE Tech. Rev. 2023, 40, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaki, J.; Ghosh, D. Deep Learning in Leaf Disease Detection (2014–2024): A Visualization-Based Bibliometric Analysis. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 95291–95308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.; Singh, A.P.; Chug, A.; Singh, D. A systematic literature review of machine learning techniques deployed in agriculture: A case study of the banana crop. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 87333–87360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinshaw, N.T.; Assefa, B.G.; Mohapatra, S.K.; Beyene, A.M. Applications of computer vision on automatic potato plant disease detection. A systematic literature review. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 7186687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simhadri, C.G.; Kondaveeti, H.K.; Vatsavayi, V.K.; Mitra, A.; Ananthachari, P. Deep learning for rice leaf disease detection: A systematic literature review on emerging trends, methodologies, and techniques. Inf. Process. Agric. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Ghosh, A.; Chakraborty, C.; De, J.N.; Mishra, D.P. Rice leaf disease identification and classification using machine learning techniques. A comprehensive review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, D.G., Jr.; Pinto, F.A.C.; Queiroz, D.M.; Viana, P.A. Fall armyworm damaged maize plant identification using digital images. Biosyst. Eng. 2003, 85, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.N.; Yang, B. Research on recognition of maize disease based on mobile internet and support vector machine technique. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 905, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishengoma, F.S.; Rai, I.A.; Said, R.N. Identification of maize leaves infected by fall armyworms using UAV-based imagery and convolutional neural networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 184, 106124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ak Entuni, C.J.; Zulcaffle, T.M.A. Simple Screening Method of Maize Disease using Machine Learning. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. (IJITEE) 2019, 9, 464–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwanosike, M.R.O.; Mabagala, R.B.; Kusolwa, P.M. Effect of northern leaf blight (Exserohilum turcicum) severity on yield of maize (Zea mays L.) in Morogoro, Tanzania. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2015, 4, 465–474. [Google Scholar]

- DeChant, C.; Wiesner-Hanks, T.; Chen, S.; Stewart, E.L.; Yosinski, J.; Gore, M.A.; Nelson, R.J.; Lipson, H. Automated identification of northern leaf blight-infected maize plants from field imagery using deep learning. Phytopathology 2017, 107, 1426–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyomwungere, D.; Mwangi, W.; Rimiru, R. Multi-task neural networks convolutional learning model for maize disease identification. In Proceedings of the IST-Africa Conference (IST-Africa), Virtual, 16–20 May 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, M. Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm for Disease Detection in Maize Leaf using Machine Learning Techniques. J. Phys. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 14, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabavathy, K.; Kumar, C.H.; Sairahul, N.S.; Johnson, S. Multi-Modal Transfer Learning with DenseNet and Random Forest for Accurate Detection of Powdery Mildew in Rice & Maize Crops. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC), Salem, India, 4–6 May 2023; pp. 978–983. [Google Scholar]

- Mduma, N.; Laizer, H. Machine learning imagery dataset for maize crop. a case of Tanzania. Data Brief 2023, 48, 109108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Zhang, D.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, X. Detection of corn and weed species by the combination of spectral, shape, and textural features. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, R.; Lv, Z.; Yan, J.; Chen, G.; Zhao, F.; Zeng, L.; Xu, B. Development of Spectral Disease Indices for Southern Corn Rust Detection and Severity Classification. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Zhi, Z.; Shi, Y.; Liu, G.; Ou, Q. Diagnosis of corn leaf diseases by FTIR spectroscopy combined with machine learning. Vib. Spectrosc. 2024, 135, 103744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokey, T.; Jain, S. Quality assessment of crops using machine learning techniques. In Proceedings of the Amity International Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AICAI), Dubai, Saudi Arabia, 4–6 February 2019; pp. 259–263. [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, K.P.; Das, H.; Sahoo, A.K.; Moharana, S.C. Maize leaf disease detection and classification using machine learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing, Analytics, and Networking, Big Island, HI, USA, 17–20 February 2020; pp. 659–669. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, D. Detection of maize disease using random forest classification algorithm. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. (TURCOMAT) 2021, 12, 715–720. [Google Scholar]

- Pitchai, R.; Vaishnavi, P.; Supraja, P.; Shirisha, C.; Madhubabu, C. Automatic Classification and Detection of Maize Leaf Diseases Using Machine Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Augmented Intelligence and Sustainable Systems (ICAISS), Trichy, India, 23–25 August 2023; pp. 406–410. [Google Scholar]

- Leena, N.; Saju, K.K. Classification of macronutrient deficiencies in maize plants using machine learning. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. (IJECE) 2021, 8, 4197–4203. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumo, B.S.; Heryana, A.; Mahendra, O.; Pardede, H.F. Machine learning-based automatic detection of corn-plant diseases using image processing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer, Control, Informatics and Its Applications (IC3INA), Tangerang, Indonesia, 1–2 November 2018; pp. 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Aurangzeb, K.; Akmal, F.; Khan, M.A.; Sharif, M.; Javed, M.Y. Advanced machine learning algorithm-based system for crop leaf disease recognition. In Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Data Science and Machine Learning Applications (CDMA), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 4–5 March 2020; pp. 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.C.; Ji, Y.; Wei, L.; Hu, H. A New Image Classification Approach to Recognizing Maize Diseases. Recent Adv. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2020, 13, 331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Agustiono, W. An ensemble-of-classifiers approach for corn leaf-based diseases detection. In Proceedings of the 7th Information Technology International Seminar (ITIS), Surabaya, Indonesia, 6–8 October 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.; Mishra, R.; Sharma, A. Maize Plant Leaf Disease Classification Using Supervised Machine Learning Algorithms. Fusion Pract. Appl. 2023, 13, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilaru, R.; Raju, K.M. Prediction of maize leaf disease detection to improve crop yield using machine learning based models. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Recent Trends in Computer Science and Technology (ICRTCST), Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, 11–12 February 2022; pp. 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.; Dutta, M.K. An automated image processing method for segmentation and quantification of rust disease in maize leaves. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computational Intelligence & Communication Technology (CICT), Ghaziabad, India, 9–10 February 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Resti, Y.; Irsan, C.; Amini, M.; Yani, I.; Passarella, R. Performance improvement of decision tree model using fuzzy membership function for classification of corn plant diseases and pests. Sci. Technol. Indones. 2022, 7, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, J.; Agrawal, U. Classification of Maize leaf diseases from healthy leaves using Deep Forest. J. Artif. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noola, D.; Basavaraju, D.R. Corn leaf image classification based on machine learning techniques for accurate leaf disease detection. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. (IJECE) 2022, 12, 2509–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, V.; Kirubakaran, G. Comprehensive Analysis of Corn and Maize Plant Disease Detection and Control Using Various Machine Learning Algorithms and Internet of Things. Philipp. J. Sci. 2023, 152, 2245–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipindu, L.; Mupangwa, W.; Mtsilizah, J.; Nyagumbo, I.; Zaman-Allah, M. Maize kernel abortion recognition and classification using binary classification machine learning algorithms and deep convolutional neural networks. AI 2020, 1, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noola, D.A.; Basavaraju, D.R. Corn Leaf Disease Detection with Pertinent Feature Selection Model Using Machine Learning Technique with Efficient Spot Tagging Model. Rev. Intell. Artif. 2021, 35, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Singh, V.; Gourisaria, M.K.; Sharma, A.; Das, H. Comparative analysis of CNN Architectures for maize crop disease. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Technology-Signal and Information Processing, Nagpur, India, 29–30 April 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Chen, A.; Cai, W.; Wang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Li, L. Multi-channel feature fusion networks with hard coordinate attention mechanism for maize disease identification under complex backgrounds. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 203, 107486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, W.; Rochman, E.M.S.; Satoto, B.D.; Rachmad, A. Machine learning and deep learning for maize leaf disease classification: A review. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2406, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, S.I.U.; Raza, A.; Lan, Y.; Wang, S. Identification of Pest Attack on Corn Crops Using Machine Learning Techniques. Eng. Proc. 2023, 56, 183. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Xing, Z.; Wang, H.; Gao, X.; Dong, X.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Classification and localization of maize leaf spot disease based on weakly supervised learning. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1128399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gookyi, D.A.N.; Wulnye, F.A.; Arthur, E.A.E.; Ahiadormey, R.K.; Agyemang, J.O.; Agyekum, K.O.-B.O.; Gyaang, R. TinyML for Smart Agriculture. Comparative Analysis of TinyML Platforms and Practical Deployment for Maize Leaf Disease Identification. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Sohail, S.S.; Madsen, D.Ø.; Khare, B.K. Deep transfer learning for fine-grained maize leaf disease classification. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qiao, Y.; Meng, F.; Fan, C.; Zhang, M. Identification of maize leaf diseases using improved deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 30370–30377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahila Priyadharshini, R.; Arivazhagan, S.; Arun, M.; Mirnalini, A. Maize leaf disease classification using deep convolutional neural networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 8887–8895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zhang, S.; Wang, P.; Xu, G.; Wang, D.; Qian, Y. The identification of corn leaf diseases based on transfer learning and data augmentation. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering, Beijing, China, 22–24 May 2020; pp. 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, K.P.; Sahoo, A.K.; Das, H. A CNN approach for corn leaves disease detection to support digital agricultural system. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), Tirunelveli, India, 15–17 June 2020; pp. 678–683. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Wiesner-Hanks, T.; Stewart, E.L.; DeChant, C.; Kaczmar, N.; Gore, M.A.; Nelson, R.J.; Lipson, H. Autonomous detection of plant disease symptoms directly from aerial imagery. Plant Phenome J. 2019, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.N.; Ghosh, H.; Rahat, I.S.; Reddy, C.V.R. Advanced Deep Learning Models for Corn Leaf Disease Classification: A Field Study in Bangladesh. Eng. Proc. 2023, 59, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner-Hanks, T.; Stewart, E.L.; Kaczmar, N.; DeChant, C.; Wu, H.; Nelson, R.J.; Lipson, H.; Gore, M.A. Image set for deep learning. Field images of maize annotated with disease symptoms. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richey, B.; Majumder, S.; Shirvaikar, M.V.; Kehtarnavaz, N. Real-time detection of maize crop disease via a deep learning-based smartphone app. In Real-Time Image Processing and Deep Learning; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; Volume 11401, pp. 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Yang, Y.; He, X.; Wu, X. Northern maize leaf blight detection under complex field environment based on deep learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 33679–33688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syarief, M.; Setiawan, W. Convolutional neural network for maize leaf disease image classification. Telkomnika (Telecommun. Comput. Electron. Control) 2020, 18, 1376–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanksha, E.; Sharma, N.; Gulati, K. OPNN: Optimized probabilistic neural network-based automatic detection of maize plant disease. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Coimbatore, India, 20–22 January 2021; pp. 1322–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, D.; Zeb, A.; Nanehkaran, Y.A. Attention embedded lightweight network for maize disease recognition. Plant Pathol. 2021, 70, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Marwaha, S.; Arora, A.; Paul, R.K.; Hooda, K.S.; Sharma, A.; Grover, M. Image-based identification of maydis leaf blight disease of maize (Zea mays) using deep learning. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 91, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthi, M.; Sankavi, R.S.; Aishwarya, V.; Chithra, B. Maize Leaf Diseases Identification using Data Augmentation and Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICO-SEC), Trichy, India, 7–9 October 2021; pp. 1672–1677. [Google Scholar]

- Sibiya, M.; Sumbwanyambe, M. Automatic fuzzy logic-based maize common rust disease severity predictions with thresholding and deep learning. Pathogens 2021, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, C.; Heidari, A.A.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H.; Mafarja, M.; Turabieh, H. Corn leaf diseases diagnosis based on K-means clustering and deep learning. IEEE Access 2022, 9, 143824–143835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasrotia, S.; Yadav, J.; Rajpal, N.; Arora, M.; Chaudhary, J. Convolutional neural network based maize plant disease identification. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 218, 1712–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, A. Ensemble-based ERDNet model for leaf disease detection in rice and maize crops. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Paradigm Shifts in Communications Embedded Systems, Machine Learning and Signal Processing (PCEMS), Nagpur, India, 5–6 April 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Waheed, A.; Goyal, M.; Gupta, D.; Khanna, A.; Hassanien, A.E.; Pandey, H.M. An optimized dense convolutional neural network model for disease recognition and classification in corn leaf. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 175, 105456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri Wahyuningrum, R.; Kusumaningsih, A.; Putra Rajeb, W.; Eddy Purnama, I.K. Classification of Corn Leaf Disease Using the Optimized DenseNet-169 Model. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information Technology: IoT and Smart City, Guangzhou, China, 22–25 December 2022; pp. 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bachhal, P.; Kukreja, V.; Ahuja, S. Maize leaf diseases classification using a deep learning algorithm. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), Belgaum, India, 26–28 May 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mafukidze, H.D.; Owomugisha, G.; Otim, D.; Nechibvute, A.; Nyamhere, C.; Mazunga, F. Adaptive thresholding of CNN features for maize leaf disease classification and severity estimation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.-Q.; Qiao, J.-F.; Wang, R.; Yu, H.-L.; Wang, C.; Taylor, K.; Pan, H.-Y. Intelligent diagnosis of northern corn leaf blight with deep learning model. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Tiwari, A.; Gupta, R.K. Deep transfer modeling for classification of maize plant leaf disease. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 6051–6067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahli, S.; Masood, M. Efficient attention-based CNN network (EANet) for multi-class maize crop disease classification. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1003152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.; Darwish, A.; Hassanien, A.E.; Soliman, M. End-to-end deep learning model for corn leaf disease classification. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 31103–31115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chy, M.S.R.; Mahin, M.R.H.; Islam, M.F.; Hossain, M.S.; Rasel, A.A. Classifying Corn Leaf Diseases using Ensemble Learning with Dropout and Stochastic Depth Based Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Machine Learning Technologies, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–12 March 2023; pp. 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, A.; Sethy, P.K.; Behera, S.K. Maize disease identification based on optimized support vector machine using deep feature of DenseNet201. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Marwaha, S.; Deb, C.K.; Nigam, S.; Arora, A.; Hooda, K.S.; Soujanya, P.L.; Aggarwal, S.K.; Lall, B.; Kumar, M.; et al. Deep learning-based approach for identification of diseases of maize crop. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jajoo, P.; Jain, M.K.; Jangir, S. Plant Disease Detection Over Multiple Datasets Using AlexNet. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Management & Machine Intelligence, Jaipur, India, 23–24 December 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, C.; Yang, G.; Ye, Q. One-stage disease detection method for maize leaf based on multi-scale feature fusion. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craze, H.A.; Pillay, N.; Joubert, F.; Berger, D.K. Deep learning diagnostics of gray leaf spot in maize under mixed disease field conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Vishnoi, J.; Rao, A.S. Disease detection in maize plant using deep convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 22–24 June 2022; pp. 1330–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Wei, H.; Lu, Y.; Ling, B.; Qin, Y. A survey of deep learning-based object detection methods in crop counting. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 215, 108425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Adil, M.A.A.; Talukder, M.A.; Ahamed, M.K.U.; Uddin, M.A.; Hasan, M.K.; Sharmin, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Debnath, S.K. DeepCrop: Deep learning-based crop disease prediction with web application. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Zafar, N.; Tahir, M.N.; Aqib, M.; Waheed, H.; Haroon, Z. A mobile-based system for maize plant leaf disease detection and classification using deep learning. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1079366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Lee, J. Detection of Northern Corn Leaf Blight Disease in Real Environment Using Optimized YOLOv3. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26–29 January 2022; pp. 0475–0480. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, G.; Liu, L. Study on target detection of maize leaf disease based on YOLOv5-MC. In Proceedings of the 3rd Guang-dong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area Artificial Intelligence and Big Data Forum, Guangzhou, China, 22–24 September 2023; pp. 436–440. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, C.; Zeng, T.; Zhang, H.; Fu, W.; Wang, L.; Yao, S. Maize small leaf spot classification based on improved deep convolutional neural networks with a multi-scale attention mechanism. Agronomy 2022, 12, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, M.C.A.; Gonzales, M.A.C.; Pasia, J.C.G.; Tolentino, E.B.; Mandap, J.A.L.; Macasero, J.B.M. Detection of Corn Leaf Diseases Using Image Processing and YOLOv7 Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Intelligent Information Technology, Xi’an, China, 23–25 February 2024; pp. 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Vani, R.; Sanjay, G.H.; Sathish, M.; Praveena, M. An Innovative Method for Detecting Disease in Maize Crop Leaves Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Automation, Computing and Renewable Systems (ICACRS), Pudukkottai, India, 11–13 December 2023; pp. 890–895. [Google Scholar]

- Bachhal, P.; Kukreja, V.; Ahuja, S.; Lilhore, U.K.; Simaiya, S.; Bijalwan, A.; Al-roobaea, R.; Algarni, S. Maize leaf disease recognition using PRF-SVM integration: A breakthrough technique. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Rana, A.; Gupta, A.; Sharma, R.; Kukreja, V. An enhanced CNN-LSTM based hybrid deep learning model for corn leaf eye spot disease classification. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies (CSNT), Bhopal, India, 8–9 April 2023; pp. 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, P.S.; Sheorey, T.; Ojha, A. VGG-ICNN. A Lightweight CNN model for crop disease identification. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Bao, R.; Yan, B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, S. LSANNet. A lightweight convolutional neural network for maize leaf disease identification. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 248, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Su, Q.; Guo, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, G. Semi-Supervised One-Stage Object Detection for Maize Leaf Disease. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, R.; Aslam, W.; Aziz, R. An Early and Smart Detection of Corn Plant Leaf Diseases Using IoT and Deep Learning Multi-Models. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 23149–23162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padshetty, S.; Umashetty, A. Agricultural innovation through deep learning: A hybrid CNN-Transformer architecture for crop disease classification. J. Spat. Sci. 2024, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhu, R. Maize leaf disease recognition based on TC-MRSN model in sustainable agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 221, 108915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwini, C.; Sellam, V. An optimal model for identification and classification of corn leaf disease using hybrid 3D-CNN and LSTM. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 92, 106089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Tripathi, A.K.; Daga, P.; Nidhi, M.; Mittal, H. ClGanNet. A novel method for maize leaf disease identification using ClGan and deep CNN. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2024, 120, 117074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong-Dang, V.-L.; Thai, H.-T.; Le, K.-H. TinyResViT. A lightweight hybrid deep learning model for on-device corn leaf disease detection. Internet Things 2025, 30, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerthagiri, P.; Ruby, A.U.; Chandran, J.G.C.; Sardar, T.H.; Ahamed Shafeeq, B.M. Deep SqueezeNet learning model for diagnosis and prediction of maize leaf diseases. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, H. Maize leaf disease recognition based on improved MSRCR and OSCRNet. Crop Prot. 2024, 183, 106757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Wang, L.; Xie, Q.; Gao, R.; Su, Z.; Li, Y. A novel deep learning method for maize disease identification based on small sample-size and complex background datasets. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 75, 102011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, M.; Nawaz, M.; Nazir, T.; Javed, A.; Alkanhel, R.; Elmannai, H.; Dhahbi, S.; Bourouis, S. MaizeNet. A deep learning approach for effectively recognizing maize plant leaf diseases. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 52862–52876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, F.; Song, Y.; Yu, X.; Nie, C.; Liu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zou, D.; Wang, C.; Yin, D.; Yang, W.; et al. A novel method for maize leaf disease classification using the RGB-D post-segmentation image data. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1268015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourish, A.; Batra, S.; Sharoon, K.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, M. A Study of Deep Learning based Techniques for the Detection of Maize Leaf Disease. A Short Review. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), Madurai, India, 17–19 May 2023; pp. 134–141. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, H.; Udayangani, H.; Umesha, K.; Lankasena, N.; Liyanage, C.; Thambugala, K. Maize leaf disease detection using convolutional neural network: A mobile application based on pre-trained VGG16 architecture. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2024, 53, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Sachan, R.; Rajpal, D. Deep convolutional neural network-based detection system for real-time corn plant disease recognition. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 167, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, M.U.; Rho, S.; Paul, A.; Seo, S. Detection of plant diseases in the images using Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 16–18 December 2020; pp. 738–739. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, L.; Li, K. Deep learning-based identification of maize leaf diseases is improved by an attention mechanism. Self-attention. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 864486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnoi, S.; Persis, J. Intelligent crop management system for improving yield in maize production. Evidence from India. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2024, 73, 3319–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Sun, S.; Huang, W.; Sheng, B.; Li, P.; Feng, D.D. EAPT: Efficient attention pyramid transformer for image processing. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2021, 25, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ren, G. Intelligent leaf disease diagnosis: Image algorithms using Swin Transformer and federated learning. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 4815–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraddi, S.; Desai, S.; Deshpande, A. Deep learning for agricultural plant disease detection. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Data Science, Machine Learning and Applications, Pune, India, 21–22 November 2020; pp. 864–871. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, N.; Rani, G.; Dhaka, V.S.; Gupta, K.; Nayaka, S.C.; Vocaturo, E.; Zumpano, E. Disease detection, severity prediction, and crop loss estimation in MaizeCrop using deep learning. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2022, 6, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Li, H.; Hu, G.; Liang, D. Identification of maize leaf diseases using the SKPSNet-50 convolutional neural network model. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2022, 35, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyanth, L.G.; Ahmad, A.; Saraswat, D. A two-stage deep-learning based segmentation model for crop disease quantification based on corn field imagery. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 3, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Kukreja, V.; Srivastava, P. Agriculture Breakthrough: Federated ConvNets for Unprecedented Maize Disease Detection and Severity Estimation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Circuit Power and Computing Technologies (ICCPCT), Kollam, India, 10–11 August 2023; pp. 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, P.; Sharma, A.; Ali, F.; Kukreja, V. CNN and Random Forest for Maize Diseases Identification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Automation and Computation (AUTOCOM), Dehradun, India, 14–16 March 2024; pp. 91–94. [Google Scholar]

| Ref | Crop | Region | Paper Count | Period Covered | Dataset | Proposed Model | Results | Summarize | Best Model | Research Gap | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [19] | Major Plants (Including Maize Crop) | Global Issues | 45 | 2004 to 2019 |  | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | 2019 |

| [23] | Banana Crop | 10 regions—major producers of bananas in the World | 60 | 2009 to 2021 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 2022 |

| [24] | Potato Plant | Global Issues | 105 | 2005 to 2022 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | 2022 |

| [16] | Major Plants (Including Maize Crop) | Global Issues | 76 | 2005 to 2022 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | 2022 |

| [17] | Major Plants (Including Maize Crop) | Global Issues | 256 | 2006 to 2022 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 2023 |

| [21] | Major Plants (Including Maize Crop) | Global Issues | 55 | 2006 to 2022 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 2023 |

| [18] | Major Plants (Including Maize Crop) | Global Issues | 176 | 2010 to 2022 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | 2023 |

| [22] | Major Plants (Including Maize Crop) | Global Issues | 57 | 2014 to 2024 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | 2024 |

| [25] | Rice Crop | Global Issues | 166 | 2011 to 2024 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 2024 |

| [26] | Rice Crop | Global Issues | 127 | 1999 to 2022 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | 2025 |

| Our Work | Maize Crop | Global Issues (India, Tanzania- Majority) | 102 | 2017 to 2025 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 2025 |

Partially Reported.

Partially Reported.| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Transparency in Datasets | Sources, size, class distribution, preprocessing, and any ambiguous or insufficient description of the dataset should all be clearly disclosed. |

| Validation of Robustness | Single train-test split or robust validation (cross-validation or independent test set). |

| Metric Completeness | Only accuracy was presented, along with other metrics (precision, recall, F1-score, and confusion matrix). |

| Field Validation | Evaluation of images taken in real life (Field) or photos taken only in a laboratory. |

| Class Imbalance Handling | Explicitly comment on the use of (Resampling/Weighting/Augmentation) or Not mentioned. |

| Metric | Minimum (%) | Median (%) | Maximum (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 72 (approx.) | 92–95 | 99.9 (approx.) |

| Precision | 70 (approx.) | 90–93 | 99 (approx.) |

| Recall | 68 (approx.) | 89–92 | 99 (approx.) |

| F1-Score | 69 (approx.) | 90–93 | 99 (approx.) |

| Abbreviation | Full Form | Abbreviation | Full Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network | EANet | External Attention Transformer |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network | SKPSNet | Select Kernel Point Switch Network |

| DL | Deep Learning | SFTA | Segmented Fractal Texture Analysis |

| ML | Machine Learning | SDI | Stress-Related Vegetation Indices |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory | SCR | Southern Corn Rust |

| DT | Decision Tree | NB | Naïve Bayes |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine | GCH | Global Color Histogram |

| KNN | K–K-Nearest Neighbor | CCV | Color Coherence Vector |

| LR | Logistic Regression | LBP | Local Binary Pattern |

| SL | Supervised Learning | CPDA | Color Processing Detection Algorithm |

| CART | Classification and Regression Tree | SPLD | Spot Tagging Leaf Disease |

| RF | Random Forest | PFS | Pertinent Feature Selection |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once | CAM | Class Activation Mapping |

| VGG | Visual Geometry Group | EKNN | Enhanced K-Nearest Neighbor |

| HOG | Histogram of Gradients | ACO | Ant Colony Optimization |

| GLCM | Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix | LVCEL | Least Validation Cross-Entropy Loss |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis | NLB | Northern Leaf Blight |

| HCA | Hard Coordinated Attention | SLB | Southern Leaf Blight |

| LTP | Local Ternary Patterns | OPNN | Optimized Probabilistic Neural Network |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network | CBAM | Convolutional Block Attention Modules |

| DCNN | Deep Convolutional Neural Network | GLS | Gray Leaf Spot |

| PSPNet | Pyramid Scene Parsing Network | NLS | Northern Leaf Spot |

| MSRCR | Multi-Scale Retinex with Color Restoration | UAV | Uncrewed Aerial Vehicle |

| OSCRNet | Octave and Self-Calibrated ResNet | SSD | Single Shot Multi-Box Detector |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network | mAP | Mean Average Precision |

| Ref | Disease Type | Key Visual Symptoms | Typical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| [30] | Northern Leaf Blight (NLB) | Long gray-green lesions along veins | Reduced photosynthesis |

| [31] | Gray Leaf Spot (GLS) | Rectangular gray/brown lesions | Yield reduction |

| [30] | Rust | Yellowish–brown pustules | Premature leaf senescence |

| [32] | Grouped leaf diseases | Overlapping lesion patterns | Label ambiguity |

| [28,29] | General infections | Discoloration, wilting, stunting | Reduced vigor |

| [30,31] | Healthy leaf | Uniform green texture | Reference class |

| S. No | Disease Type | Disease Name | Disease Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fungal Diseases | Gray Leaf Spot |  | Gray Leaf Spot (GLS) is a fungal disease caused by the fungus Cercospora zeae-maydis. It can lead to significant yield losses in maize, especially in humid, hot regions. It can reduce maize yield by up to fifty percent, with the potential for even greater losses if infection occurs early in the growing season. |

| 2 | Northern and Southern Corn Leaf Blight |  | Northern Corn Leaf Blight and Southern Corn Leaf Blight are serious foliar diseases of maize caused by pathogenic fungi. These diseases can significantly reduce maize yields, potentially leading to total crop loss. Under favorable conditions, economic losses from these diseases may also occur. | |

| 3 | Common Rust |  | Rust, a fungal disease, can significantly impact maize production and cause widespread financial losses. | |

| 4 | Cercospora Leaf Spot |  | Another fungal pathogen, Fox Spot, caused by the pathogen Cercospora sorghi var. maydis in maize, exhibits similar symptoms and has comparable damaging effects on the crop as Gray Leaf Spot, with potential yield and financial losses for producers. | |

| 5 | Physoderma maydis |  | This pathogen, also known as Physoderma brown spot or Physoderma leaf spot, threatens maize crops, especially in warm, moist regions. | |

| 6 | Helminthosporium turcicum (Exserohilum turcicum) |  | This fungal pathogen causes Northern Corn Leaf Blight (NCLB) disease in maize. It causes foliar diseases in maize and is a significant problem in regions with a climate conducive to disease development. Infected crops may exhibit visible signs of nutrient deficiencies due to poor nutrient absorption. | |

| 7 | Maydis Leaf Blight |  | The disease is usually associated with the fungus Exserohilum turcicum, but can also be linked to the virus maize leaf blight virus (MLBV). Infected plants may experience deficiencies because the disease can damage roots and impair nutrient uptake. | |

| 8 | Powdery Mildew |  | This fungal disease can infect many plants and crops, including maize (corn), and can slow their growth, leading to smaller plants and reduced grain yields. | |

| 9 | Dark Spot Diseases |  | Diseases such as northern and southern corn leaf blight can significantly reduce photosynthesis and harm plants, thereby lowering maize yields. | |

| 10 | Viral Diseases | Maize Streak Virus (MSV) |  | This viral disease infects maize in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, especially in Africa. Infection with maize streak virus can weaken maize crops and impair their nutrient uptake, leading to reduced health and productivity. |

| 11 | Mosaic Virus |  | In maize (Zea mays), the term “mosaic virus” generally refers to viruses that cause symptoms such as dark and light leaf streaks, which can even appear as bright emerald green. Infected plants may exhibit poor nutrient uptake and utilization, leading to nutritional deficiencies and reduced growth and productivity. | |

| 12 | Maize Eyespot Disease |  | It is related to the Maize Eyespot Virus (MEV). Although the virus receives less attention than some other maize viral infections, it can still significantly reduce yields. Affected plants will show nutritional deficiencies due to decreased nutrient uptake and overall health decline. | |

| 13 | Bacterial Diseases | Goss’s Wilt (Goss’s Bacterial Wilt) |  | This bacterially induced disease can negatively affect the maize plant. Infected plants often experience nutrient deficiencies, leading to reduced absorption, uptake, growth, and yield. |

| 14 | Other Diseases | Armyworm Pest |  | Armyworms, especially the Fall Armyworm, can damage maize leaves, reducing yields and causing significant crop losses, especially when infestations occur during the early stages of plant development. |

| 15 | Maize Kernel Abortion |  | Maize abortion results in an inadequate harvest when developing kernels abort and fail to mature during the grain-filling period, which determines yield. This can happen due to diseases, unhealthy plants, or adverse environmental conditions. As a result, there is a lower kernel number per ear and a decrease in overall yield. | |

| 16 | Maize Foliar Diseases |  | A variety of foliar diseases, including Common Rust, SCLB, and NCLB, can significantly impact maize growth and yield by disrupting nutrient uptake and overall plant health. | |

| 17 | Mendeley Leaf Disease |  | The field is often mistaken for other maize (Zea mays) diseases based on observed leaf symptoms. Research shows that these symptoms are not associated with any unusual disease classification. Leaf diseases can lead to fewer ears or smaller kernels, which results in lower yields and less profit for growers. |

| Ref | Dataset Source | Dataset Size | No. of Classes | Lab vs. Real | Environmental Diversity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [33] | PlantVillage/public datasets | Large | Multiple | Lab-controlled | Low–Moderate |

| [34] | Kaggle maize datasets | Medium | Multiple | Mixed | Moderate |

| [35] | Field-collected datasets | Small–Medium | Varies | Real-field | High |

| [36] | Large public maize datasets | Large | Multiple | Mixed | Moderate–High |

| Ref | Dataset (Source and Size) | Disease Classes | Ml Method (Features + Classifier) | Performance and Observations | Drawbacks | Improvement Opportunities | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [37] | 100 hyperspectral images (corn and weed plants); 70% training/30% test; collected using an imaging spectrometer | Corn and weed species (weed identification task) | Decision tree classifiers and boosting methods using hyperspectral imaging features | Global accuracy >95% with high kappa coefficients for distinguishing corn vs. weed species | Limited sample size (100 images); task focuses on weed identification, not maize disease; hyperspectral hardware may reduce deployment feasibility | Validate on larger and more diverse field datasets; test transferability to maize disease symptoms; assess lightweight alternatives for practical deployment | 2017 |

| [45] | Plantvillage maize subset; 3823 images | GLS, Common Rust, NLB, Healthy | RGB, SIFT, SURF, ORB, HOG FEATURES; CLASSIFIERS: SVM, DT, RF, NB | Best Performance: RGB With SVM | Reliance on handcrafted features; results likely influenced by controlled dataset characteristics | Evaluate robustness on real-field images; include cross-dataset testing; combine feature selection and augmentation to improve generalization | 2018 |

| [51] | Plantvillage: 120 images (60 healthy, 60 rust) | Rust vs. Healthy | Automated image processing with Rust segmentation/quantification | Computational Time: 0.48 S | Small dataset and binary setting limits generalization; PlantVillage may not reflect field variability | Expand to multi-class diseases and larger datasets; test under varying lighting/background; report accuracy/precision/recall for completeness | 2018 |

| [30] | Plantvillage: 30 images (maize leaf diseases) | Powdery Mildew, Dark Spot, Rust | Fuzzy c-means for severity/spot identification | Runtime: 19.28 S; Poi Reported (68.54% In Text) | Minimal dataset; disease set appears mixed across plants in description; limited reporting of standard classification metrics | Clarify crop-specific evaluation (maize only); increase sample size; add quantitative metrics (accuracy/f1) and validation on field images | 2019 |

| [40] | Plantvillage: 54,306 images | Common Rust, Common Smut, Fusarium Ear Rot | Supervised ML: Linear SVM, Medium Tree, Quadratic SVM, Cubic SVM | Best: Quadratic SVM, 83.3% Accuracy | Accuracy lower than many benchmark reports; model sensitivity to dataset imbalance/background not specified | Add feature selection and preprocessing analysis; report precision/recall/f1 and confusion matrix; test cross-domain generalization beyond PlantVillage | 2019 |

| [53] | Multiple datasets from different domains; includes a small maize leaf dataset (12 images reported for evaluation) | Gray Leaf Spot, Common Rust, NLB | Deep Forest Algorithm | Achieved 96.25% Accuracy on Maize Leaf Disease Classification; Outperformed, according to established definitions, Traditional ML and CNN, RNN, and transformer-based models on Small Datasets | Evaluation partly based on small-scale datasets; performance on large, real-field datasets not fully explored | Validate on large, diverse field datasets; compare computational cost with deep learning models; assess scalability | 2020 |

| [46] | Plantvillage dataset; resized RGB images (256 × 256); corn and potato leaf images | Common Rust, Early Blight, Late Blight | Handcrafted features (HOG, SFTA, LTP) with PCA for dimensionality reduction | Accuracy Ranged From 92.8% to 98.7%, Outperforming Existing Methods | Evaluated on benchmark dataset only; handcrafted features increase pipeline complexity | Extend evaluation to real-field maize images; reduce feature engineering dependency; integrate automated feature learning | 2020 |

| [56] | Dataset of 66 maize kernel images; 75% training, 25% testing | Maize Kernel Abortion | Binary ML classifiers (LR, SVM, ADB, CART, KNN) and deep CNN | SVM and LR achieved 100% Accuracy; Other ML methods > 95%; CNN also reached 100% Accuracy | Minimal dataset; task focuses on kernel abortion rather than leaf disease | Increase dataset size; evaluate robustness across varieties; extend approach to leaf disease detection | 2020 |

| [38] | Data collected from multiple field sites using vegetation indices | Southern Corn Rust (SCR) | SVM using stress-related vegetation indices (vis) | Achieved an Overall Accuracy of 87% for Detection and 70% for Severity Classification; the Scr-Sdi Model Outperformed Baseline | Accuracy for severity classification is relatively low; it relies on spectral indices | Combine image-based features with vis; integrate multispectral or hyperspectral imaging; improve severity estimation models | 2020 |

| [41] | Plantvillage dataset; 3823 images (healthy: 1192; rust: 513; nlb: 956; gls: 1162) | Common Rust, Northern Leaf Blight, Gray Leaf Spot, Healthy | Supervised ML classifiers: NB, DT, KNN, SVM, RF | Random Forest Achieved the Highest Accuracy of 79.23% | Moderate accuracy compared to recent studies; sensitivity to dataset imbalance not addressed | Incorporate feature optimization and balancing strategies; evaluate ensemble or hybrid approaches; test cross-dataset generalization | 2020 |

| [47] | Images from various sources; random split (70% training, 30% testing) | Spot, Streak, Rust | GLCM texture features and SHV color features with SVM classifier; K-means clustering for segmentation | Accuracy: Color Features 90.4%, Texture Features 80.9%, Combined Features 85.7% | Performance varies significantly by feature type; segmentation is sensitive to noise and background | Improve robustness using adaptive segmentation; integrate feature selection or ensemble strategies; validate on larger field datasets | 2020 |

| [48] | Plantvillage dataset: over 8500 cornstalk leaf images | Northern Leaf Blight, Common Rust, Cercospora Leaf Spot (Gls), Healthy | Global Color Histogram (GCH), CCV, and LBP features with an ensemble voting classifier (CART-based) | Precision 82.92%, Recall 82.55%, F1-Score 82.6% | Moderate performance compared to recent studies; handcrafted features limit adaptability | Explore automated feature learning; expand to field images; optimize ensemble depth and feature fusion | 2021 |

| [42] | Maize plant database; 3823 images | Common Rust, Gray Leaf Spot, Northern Leaf Blight, Healthy | Supervised ML: NB, DT, KNN, SVM, RF with feature extraction (shape, color, texture) | Random Forest Achieved the Highest Accuracy of 80.68% | Accuracy remains moderate; limited analysis of environmental variability | Integrate feature optimization; test ensemble or hybrid methods; evaluate robustness on real-field images | 2021 |

| [44] | Own dataset: 100 maize leaf images | Gray Leaf Spot, Common Rust, Northern Leaf Blight | KNN and SVM classifiers | KNN Achieved 95.06% Accuracy | Small dataset size limits generalization; field conditions are not specified | Increase dataset diversity; include cross-validation; test performance under varying environmental conditions | 2021 |

| [57] | Own dataset; UCI machine learning repository | Late Blight, Septoria | SPLDPFS-MLT feature selection model with machine learning classifiers | Classification Accuracy Of 97% | Focus not exclusively on maize; disease scope differs from maize leaf diseases | Adapt model specifically for maize diseases; evaluate scalability and field applicability | 2021 |

| [58] | Hybrid dataset combining plantvillage and plantdoc; 4188 images (80% training, 5% validation, 15% testing) | Common Rust, Gray Leaf Spot, Blight, Healthy | Comparison of fifteen CNN architectures for feature learning and classification | Best-Performing Model Achieved 94.99% Accuracy. | Evaluation relies mainly on curated datasets; there is a limited discussion of field robustness | Validate on real-field maize images; analyze computational efficiency and deployment feasibility | 2022 |

| [59] | Plantvillage dataset: seven classes with 7794 observations | Gray Spot, Rust, NLB, Scorch (And Related Classes) | HCA-Mffnet architecture with attention-based feature extraction and segmentation | Achieved Peak Accuracy of 97.75% And F1-Score of 97.03% | Model complexity may limit lightweight deployment; training cost is not discussed | Explore model compression and pruning; test performance on resource-constrained platforms | 2022 |

| [50] | Plantvillage dataset; 3823 images | Common Rust, Gray Leaf Spot, Northern Leaf Spot | YOLO-based segmentation; DWT and GLCM feature extraction; classifiers: SVM, RF, KNN, DT, NB | SVM Achieved Highest Accuracy of 97.25% | Dependence on handcrafted features increases pipeline complexity | Integrate end-to-end learning; evaluate robustness under varying field conditions | 2022 |

| [34] | Kaggle dataset; 3200 images (rust: 800, leaf blight: 800, healthy: 1600) | Common Rust, Leaf Blight, Healthy | Supervised ML with Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) combined with RF, SVM, KNN, NB, and LR | ACO–RF Achieved Highest Accuracy of 99.40% | Performance validated on benchmark dataset only; field generalization not assessed | Test cross-dataset generalization; assess robustness to noise and lighting variation | 2022 |

| [33] | Plantwise and Kaggle datasets; 2636 images with imbalanced classes | Common Rust, NLB, Gray Leaf Spot | Multi-Task Learning CNN (MTL-CNN) with early stopping and transfer learning | Accuracy Improved From 77.44% To 85.22% Using Transfer Learning | Class imbalance remains a challenge; moderate accuracy compared to recent dl models | Incorporate advanced balancing strategies; expand dataset diversity; explore hybrid dl–ml frameworks | 2022 |

| [54] | Plantvillage dataset: 3820 images of healthy and diseased maize leaves | Common Rust, NLB Cercospora Leaf Spot | Enhanced K-Nearest Neighbor (EKNN) with GLCM and Gabor feature extraction | Eknn Achieved 99.86% Accuracy, 99.60% Sensitivity, 99.88% Specificity, Auc 99.75% | Evaluated on a curated dataset; dependence on handcrafted texture features | Validate on field-acquired images; assess scalability and computational cost for real-time deployment | 2022 |

| [52] | Digital photographs; 761 images used for training | Leaf Rust, Downy Mildew, Leaf Blight (Disease And Pest Detection) | Fuzzy membership functions integrated with a decision tree model | Improvements Over Baseline Dt: Recall + 12.88%, Kappa + 11.13%, F-Score + 10.68% | Overall accuracy remains low; the method is sensitive to discretization choices | Integrate advanced feature extraction; test on larger, diverse maize-specific datasets | 2022 |

| [60] | Plantvillage maize leaf dataset; 2226 images per class (healthy and infected) | Common Rust, NLB, Cercospora Leaf Spot | ML classifiers (SVM, RF, LR, DT, KNN), CNN, and Deep Forest (DF) | Accuracy: SVM 79.25%, Deep Forest 96.25%; CNN outperformed traditional ML methods according to established definitions. | Mixed ML and DL evaluation may complicate fair comparison | Standardize evaluation protocols; isolate ML vs. DL performance; expand to real-field datasets | 2022 |

| [61] | Shandong University research farm; ~7000 images | Armyworm Pest (Maize-Related Insect Attack) | Deep learning CNN models (VGG-16, Conv2D) compared with AlexNet, ResNet, and YOLO variants | Achieved 99.9% Classification Accuracy | Focus on pest detection rather than leaf disease; dl-heavy approach, not lightweight | Extend to disease-specific datasets; evaluate ml–dl hybrid models for efficiency | 2023 |

| [36] | Public maize leaf dataset; 18,148 images collected in Tanzania | Streak Virus And Other Maize Leaf Diseases | Machine learning applied to computer vision tasks (classification, segmentation, detection) | Largest Publicly Available Maize Leaf Dataset; Performance Metrics Not Fully Specified | Limited reporting of classifier-specific accuracy | Encourage standardized benchmarking; apply advanced ML/DL models for comparative evaluation | 2023 |

| [49] | Plantvillage: corn (maize) gray leaf spot dataset: 513 images (80% train, 20% test) | Common Rust, Gray Leaf Spot | Feature extraction: GLCM and Gabor filters; classifiers: SVM, KNN, DT, GB | Glcm (135°) Achieved 95.05% Accuracy for DT and GB | The dataset focuses on a limited subset (513 images); the evaluation is restricted to PlantVillage. | Expand to multi-disease maize datasets; validate on field images; report broader metrics (precision/recall/f1) consistently across classifiers | 2023 |

| [43] | Plantvillage website; maize dataset: 2800 leaf images across four disease classes | Common Rust, NLB (And Related Maize Diseases In The Dataset) | Supervised ML: Random Forest (RF), SVM; feature extraction (color, texture, shape) mentioned | SVM Achieved Best Results; Overall System Accuracy Reported as less than 90% | Overall performance remains less than90%; generalization beyond PlantVillage has not been established | Improve preprocessing and feature optimization; evaluate imbalance handling; test cross-dataset and field generalization | 2023 |

| [55] | Kaggle maize dataset: 4188 images | Common Rust, Blight, Gray Leaf Spot, Healthy | Multiple ML/DL models (Google Colab): SVM, DT, RF, KNN, CNNs, gbts, LSTM, GA-based ensemble, Adaboost, XGBoost; best: XGBoost + KNN | Best Accuracy 98.77%; Precision/Recall/F1/Auroc Rated Excellent | Many models are listed without a single standardized evaluation protocol described; benchmarking may be inconsistent | Standardize train/val/test split and metrics across models; report computational cost; validate on external/field datasets | 2023 |

| [35] | High-resolution images of powdery mildew on rice and maize; minimum resolution 224 × 224 | Powdery Mildew (Rice and Maize) | Transfer learning feature extraction with densenet (pretrained on imagenet) | Accuracy 97%, Precision 96.5%, Specificity 97%, Sensitivity 97% | Disease scope is specific (powdery mildew) and includes a multi-crop setting | Extend to maize-specific multi-disease settings; evaluate robustness under field conditions; compare with lightweight backbones for deployment | 2023 |

| [62] | Combined datasets: maculates dataset (T. Wiesner-Hanks) + Kaggle; merged into a comprehensive maize leaf dataset | Maize Foliar Disease Observations (Susceptible Areas/Disease Types as Described) | Weakly supervised learning with lightweight CNNs; evaluation via MIou using image-level tags; CAM-based interpretation | Maximum Miou Reported As 55.302% | Miou indicates moderate localization performance; weak supervision may limit fine-grained accuracy | Increase pixel-level annotations for stronger supervision; improve segmentation/localization; benchmark against fully supervised baselines | 2023 |

| [63] | Datasets from Mendeley, Harvard Dataverse, and Kaggle; pre-processed/segmented on edge impulse; deployment tested on MCU simulation | Common Rust, Gray Leaf Spot, Blight, Healthy, Streak Virus | CNN-based Maize Disease Detection (MDD); Edge Impulse vs. TensorFlow for tinyml deployment | 94.60% Accuracy; MCU Simulation: 7.60 Ms Latency, 726.60 Kb RAM, 344.70 KB Classifier Flash | Performance is reported mainly in a platform-specific deployment context; dataset composition by class is not fully detailed. | Provide class-wise performance and confusion matrix; test on additional field datasets; evaluate robustness under varying capture conditions | 2024 |

| [64] | Plantvillage dataset (various plant images, including maize types) | Physoderma Maydis, Curvularia Lunata (As Described) | Deep transfer learning: inceptionv3, resnet-50, VGG-Net, Inception-resnet-V2 | Best: Resnet-50 With 87.51% Accuracy; Precision 90.33%, Recall 99.80% | The dataset is not exclusively maize-focused; potential domain bias from curated imagery | Evaluate maize-only subsets and field images; include cross-dataset validation; compare lightweight transfer models for deployment | 2024 |

| [39] | Private dataset; FTIR spectra (4000–400 cm−1); train/val: 80% (156 gls, 125 NCLB, 135 healthy); test: 20% (34 gls, 29 NCLB, 42 healthy) | NCLB, GLS, Healthy | FTIR spectroscopy + ML; VIP algorithm with RF for feature selection; VIP-KNN best among 12 models | VIP-KNN Accuracy 97.46%, Sensitivity 96.08%, Precision 95.06%; Classified Using 615 Significant Data Points; RF Models Avg Precision 93.41% | Requires spectroscopy equipment (not image-only pipeline); evaluation limited to specific fungal diseases | Combine spectral + image modalities; test scalability across regions/varieties; validate robustness under broader field sampling | 2024 |

| Naïve Bayes | CART |

|---|---|

| Decision Tree | Feature Selection |

| KNN | AdaBoost |

| SVM | GLCM |

| Random Forest | HOG |

| K-Means Clustering | PCA |

| XGBoost | HCA |

| Enhanced KNN | LR |

| Fuzzy C-Means Clustering | LTP |

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Data Collection | A substantial dataset of maize plant images, including healthy and diseased plants displaying various disease types, is needed. Field or existing datasets can be used to accomplish this task. |

| Data Preprocessing | Clean and preprocess the collected images, including resizing, cropping, and normalizing them for training the deep learning model. |

| Dataset Split | Once the dataset is prepared, it must be partitioned into train, validation, and test sets. The train dataset is to train the deep learning model. The validation dataset is used to tune the hyperparameters of the learning algorithm. The test dataset is to evaluate model performance, based on the trained and tuned model. |

| DL Model Selection | Reviewed studies typically use CNN-based architectures for image classification tasks because they are effective at learning spatial features. |

| Model Training | Train the selected deep learning model using the preprocessed training dataset. Training involves passing the images through the network and optimizing the model weights using an optimizer of the choice (e.g., stochastic gradient descent), repeating until the loss on the loss function is acceptable. |

| Model Validation | Evaluate the performance of the model previously trained on the validation dataset so that relevant performance metrics (i.e., accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score) can subsequently be computed and reported for the timing and efficiency of maize crop disease detection. |

| Model Optimization | Several studies further improved performance (e.g., learning rate, batch size, and network architecture) by optimizing hyperparameters using strategies such as grid search or random search. |

| Model Evaluation | Assess the performance of the final trained model using metrics on the test dataset, thereby establishing its effectiveness in detecting maize crop diseases. |

| Data Collection | A substantial dataset of maize plant images, including healthy and diseased plants displaying various disease types, is needed. Field or existing datasets can be used to accomplish this task. |

| Data Preprocessing | Clean and preprocess the collected images, including resizing, cropping, and normalizing them for training the deep learning model. |

| Type | Group | Overview | Representative Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task Type | Image Classification | Disease identification on maize leaves or plants | ResNet, EfficientNet, DenseNet |

| Object Detection | Identification and classification of the disease areas in maize leaf or plant images | YOLOv5, YOLOv7, Faster R-CNN | |

| Image Segmentation | Pixel-based outlining of areas of disease-affected maize leaves or plants. | U-Net, DeepLabv3+, PSPNet | |

| Architecture Type | CNN-based Architectures | Using Convolutional Networks to extract features from images of maize leaves or plants. | VGG, ResNet, Inception |

| RNN-based Architectures | Sequential or temporal modeling of extracted features from images of maize leaves or plants. | CNN–LSTM, CNN–RNN | |

| Transformer-based Architectures | Global attention-based representation learning using images of maize leaves or plants. | Vision Transformer (ViT), Swin Transformer | |

| Learning Model | Supervised Learning | Fully labeled datasets for training using images of maize leaves or plants. | CNN-based classifiers |

| Transfer Learning | Use of pre-trained backbones for maize disease classification tasks. | ResNet-50, MobileNet, VGG16 | |

| Semi-/Self-Supervised Learning | Learning from small or no-labeled image datasets for detecting diseases in maize plants or leaves. | Contrastive CNNs, Autoencoders |

| Ref | Dataset (Source and Size) | Disease Classes | Ml Method (Features + Classifier) | Performance and Observations | Drawbacks | Improvement Opportunities | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [71] | Annotated field images of maize leaves captured using UAV (sUAS), boom-mounted camera, and smartphone (size not specified) | Northern Leaf Blight (NLB) | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for lesion detection using annotated field images | CNN effectively detected NLB lesions in field images; emphasis on high-quality expert annotation (quantitative accuracy not specified) | Dataset size limited; evaluation focused on a specific disease | Expand and diversify the annotated dataset to support broader real-world applications. | 2018 |

| [65] | Google images and PlantVillage dataset, 500 maize leaf images | Gray leaf spot, NLB, rust, brown spot, round spot, healthy (9 classes) | Deep CNN models (Cifar10 and GoogleNet) | High recognition accuracy of 98.8% (Cifar10) and 98.9% (GoogleNet) | Computational resource requirements are not discussed in detail | Reduce computational complexity to enable deployment on resource-constrained systems. | 2018 |

| [66] | PlantVillage maize leaf dataset (size not specified) | Gray leaf spot, NLB, common rust, healthy | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Classification accuracy of 97.89% achieved on maize leaf diseases | Evaluation limited to the controlled dataset | Not specified. | 2019 |

| [69] | Field-acquired maize leaf images captured via UAV across 10 flights (sub-images used for training; size not specified) | Northern Leaf Blight (NLB) | CNN trained on UAV-derived sub-images for field-based disease detection | Achieved 95.1% accuracy when tested on field images | Did not evaluate performance on larger or multi-disease datasets | Validate the model using larger and more diverse datasets. | 2019 |

| [130] | Plant disease image dataset (source and size not specified) | Multiple plant diseases (not maize-specific) | CNN-based deep learning approach trained using GPUs | Reported high detection accuracy (exact value not specified) | Disease- and crop-specific performance is not detailed | Improve model generalization across different plant species and disease types. | 2020 |

| [125] | Kaggle crop disease dataset (size not specified) | Leaf diseases (crop-specific classes not detailed) | Faster R-CNN for disease detection | Detection accuracy exceeding 97%, enabling early-stage disease identification | Dataset characteristics and disease granularity are not fully described | Enhance the framework to support real-time disease detection applications. | 2020 |

| [67] | PlantVillage dataset, 50,000 plant images (4354 maize leaf images) | NLB, gray leaf spot, common rust, healthy | CNN with transfer learning and data augmentation | Recognition accuracy of 97.6% with improved classification speed | Evaluation limited to controlled PlantVillage images | Not specified. | 2020 |

| [124] | PlantVillage dataset + field images from Sultanpur and Raebareli districts (size not specified) | Leaf blight, rust, healthy | Deep Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | An accuracy of 88.46% achieved using optimized pooling and hyperparameters | Performance lower than later DL approaches; dataset size not clearly specified | Incorporate additional maize disease datasets to improve robustness. | 2020 |

| [68] | PlantVillage dataset, 3823 maize leaf images | Common rust, NLB, Cercospora leaf spot, healthy | CNN-based deep learning model | High accuracy of 98.78%, with reduced training time | Limited evaluation beyond the PlantVillage dataset | Integrate and compare additional deep learning architectures to enhance performance. | 2020 |

| [72] | PlantVillage dataset + annotated NLB dataset (≈1100 images) | Healthy vs. NLB-damaged leaves | Pre-trained ResNet-50 (transfer learning) | Accuracy ≈99% and F1-score ≈99% on unseen data | Focused mainly on NLB; limited disease diversity | Improve application usability and extend functionality to other crops. | 2020 |

| [73] | Open-source NLB dataset (size not specified) | Northern maize leaf blight (NLB) | CNN-based Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) with multi-scale feature fusion | Mean Average Precision (mAP): 91.83%, outperforming single-stage models | Evaluated primarily on the NLB only | Extend the detection framework to multiple diseases and optimize real-time processing. | 2020 |

| [74] | Maize leaf image dataset (4 classes, 50 images per class; resolution 256 × 256) | Common rust, NLB, healthy | CNN feature extraction (AlexNet, GoogLeNet, InceptionV3, ResNet, VGG) + ML classifiers | Best accuracy 93.5% using AlexNet with SVM | Small dataset size limits generalization | Test the model under more diverse environmental conditions and datasets. | 2020 |

| [83] | Maize leaf image dataset, 12,332 images (250 × 250 pixels) | NLB, Cercospora leaf spot, common rust, healthy | DenseNet CNN architecture | Optimized accuracy of 98.06% with fewer parameters than other CNNs | Evaluation focused on a single dataset | Evaluate the proposed architecture on multiple datasets to assess generalization. | 2020 |

| [75] | Leaf spot, rust, gray spot | Not specified | Optimized Probabilistic Neural Network (OPNN) with Artificial Jelly Optimization (AJO) | Accuracy up to 95.5% | Automated plant leaf disease detection | Improve discrimination between visually similar disease classes. | 2021 |

| [76] | Maize eyespot, common smut, southern rust, Goss wilt | PlantVillage + open maize dataset | CNN with transfer learning (Mobile-DANet) | Average accuracy 95.86%; 98.50% on the open maize dataset | Practical and feasible maize disease identification | Enhance usability for real-time field deployment. | 2021 |

| [77] | Maydis leaf blight | Private dataset | Deep CNN based on GoogleNet architecture | Classification accuracy 99.14% | High classification accuracy on independent test data | Validate the proposed methodology across a broader range of datasets. | 2021 |

| [78] | Common rust, NLB, gray leaf spot, brown spot | Google and Kaggle datasets (4149 images) | CNN using the GoogleNet architecture | Training accuracy 99.87%; testing accuracy 98.55% | Improved diagnostic accuracy for multiple maize diseases | Develop a software or web-based interface to visualize prediction results. | 2021 |

| [79] | Common rust (severity levels: early, middle, late, healthy) | PlantVillage | CNN with the VGG-16 network | Validation accuracy 95.63%; testing accuracy 89% | Effective severity-level classification | Improve accessibility by simplifying image processing and implementation requirements. | 2021 |

| [84] | Common rust, leaf blight, leaf spot | PlantVillage + field data (Madura, Indonesia) | Modified DenseNet-169 CNN with Adam optimizer | Average accuracy 99.32% (Adam > SGD) | Enhanced feature representation with deeper architecture | Conduct broader comparisons across multiple optimization strategies. | 2021 |

| [89] | NLB, common rust, Cercospora leaf spot | PlantVillage | CNN with Efficient Attention Network (EANet) | Training 99.89%, testing 98.94% | Attention highlights diseased regions while suppressing noise | Extend classification to additional categories of maize leaf diseases. | 2022 |

| [90] | Gray spot, common rust, NLB | PlantVillage (Kaggle subset) | End-to-end DL with EfficientNetB0 + DenseNet121 | Accuracy up to 98.56% | Improved feature representation via concatenation | Expand the model to support a wider range of plant diseases. | 2022 |

| [96] | Gray leaf spot | Field + PlantVillage datasets | CNN with Mask R-CNN background removal | Accuracy 94.1% | Background removal enhances detection | Introduce more dynamic and diverse datasets to improve adaptability. | 2022 |

| [97] | Leaf blight, leaf rust, leaf spots | Own dataset | DCNN with transfer learning | Accuracy 97.93% | Reliable disease identification | Further refine and optimize the proposed model architecture. | 2022 |

| [93] | Maydis leaf blight, TLB, banded leaf and sheath blight | Own dataset | Deep CNN | Accuracy 95.99%, recall 95.96% | Effective for multiple diseases | Integrate the model into a smartphone-based diagnostic application. | 2022 |

| [94] | Leaf diseases (multiple crops) | PlantVillage, Mendeley, Kaggle | AlexNet | Accuracy 93.16% | Multi-dataset robustness | Explore alternative preprocessing techniques to enhance efficiency. | 2022 |

| [131] | Turcicum leaf blight, rust | ICAR AICRP field dataset | Deep learning architecture | Accuracy 98.50% | Severity prediction and crop loss estimation | Validate performance across larger and more diverse datasets. | 2022 |

| [95] | Maize leaf diseases | Kaggle | CNN with multi-scale feature fusion | High accuracy | Improved disease identification | Enhance global contextual awareness beyond standard convolution operations. | 2022 |

| [86] | Gray spot, common rust, NLB | PlantVillage | CNN with transfer learning | Accuracy 99% | Adaptive thresholding-based disease quantification | Need to improve training data and training time | 2022 |

| [87] | Northern corn leaf blight (NLB) | Jilin Province and greenhouse datasets | DCNN (pre-trained GoogleNet) | Accuracy 99.94% | Intelligent diagnosis capability | To expand the method to other plant species | 2022 |

| [126] | SCLB, GLS, southern corn rust | PlantVillage + field images | CNN-based model | Accuracy 98.7% | High speed and accuracy | Need to improve computational complexity | 2022 |

| [88] | Common rust, leaf spot | PlantVillage | CNN with AlexNet | Accuracy 99.16% | Automatic feature extraction from raw images | Not specified | 2022 |

| [101] | Northern leaf blight (NLB) | Private field dataset | YOLOv3 with dense blocks and CBAM | AP: 0.774/0.806/0.821 | Reduced time consumption in detection | Need to improve research methods for numerous datasets | 2022 |

| [103] | Maize small leaf spot | Private dataset | DISE-Net deep CNN | Accuracy 97.12% | High convergence and superior accuracy | Need to improve research methods for numerous datasets | 2022 |

| [80] | Gray spot, leaf spot, rust | Challenger.ai dataset | K-means clustering + deep learning | Average accuracy 93% | Effective clustering and classification | To extend the approach to other maize diseases | 2022 |

| [132] | Northern leaf spot | PlantVillage | SKPSNet-50 CNN | Accuracy 92.9% | Effective for multiple diseases | To focus on agricultural research after optimization | 2022 |

| [85] | Gray leaf spot | PlantVillage | CNN models (EfficientNetB7 best) | Accuracy 98.77% | High diagnostic precision | To improve the same method for other plant species | 2023 |

| [91] | NLB, GLS, rust | PlantVillage (38 classes) | Deep neural network-based “half-and-half learning” strategy | Accuracy 98.36% | Highly effective disease classification | Need to improve the testing and validation of a variety of plants | 2023 |

| [92] | GLS, blight, common rust | PlantVillage + Kaggle maize leaf images (4988 images; 4 maize varieties) | DenseNet201 feature extraction + optimized SVM | Accuracy 94.6% | Effective feature extraction and classification | Improve early disease detection in maize plants | 2023 |

| [133] | GLS, NLB, NLS | Proprietary field dataset (ACRE, Purdue University), 1050 leaf images under varied conditions | Two-stage semantic segmentation (SegNet, U-Net, DeepLabv3+) for lesion segmentation + severity prediction | Overall R2 = 0.96 (0.92–0.97 across classes) | High precision under complex field conditions; supports severity prediction | Extend to multiple diseases and improve real-time processing | 2023 |

| [102] | Leaf spot | MDID dataset: 10,000 annotated maize disease images (LabelImg); train 70%/val 30% | YOLOv5-MC object detection | Accuracy 89.9%; recall 91.6% | Addresses difficult detection/localization points | Need to improve AP results | 2023 |

| [98] | Pests and disease (crop counting context) | Multiple crop counting datasets (GWHD, MinneApple, Tassels Made of Maize) | Survey/review of DL models (YOLO, Faster R-CNN, SSD) for crop counting | YOLOv4 and Faster R-CNN reported ~95% in reviewed works | Comprehensive insights into DL object detection for counting | Real-time deployment challenges | 2023 |

| [99] | Bacterial leaf blight, brown spot (leaf disease detection) | Not specified | CNN-based disease detection with web application; models include CNN, VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50 | CNN 98.60%, VGG16 92.39%, VGG19 96.15%, ResNet50 98.98% | Web-based and accessible for farmers | Expand detectable diseases; enhance usability | 2023 |

| [81] | NLB, GLS, rust | PlantVillage maize crop dataset | CNN with preprocessing (CLAHE per RGB channel + HSV conversion) | Max accuracy 96.76% | Improved image quality and disease identification performance | Need to explore different plant species for disease identification | 2023 |

| [100] | Blight, mosaic virus, leaf spot | Real-world dataset from university research farm (Koont) | YOLO object detection (tested YOLOv3-tiny, v4, v5s, v7s, v8n) | Best mAP 99.04% (YOLOv8n) | Better performance; lower loss | Need to improve research methods for numerous datasets | 2023 |

| [82] | Phaeosphaeria spot, maize eyespot, GLS, Goss bacterial wilt | PlantVillage (primary source) | Soft ensemble model combining DenseNet121 + ResNet50 | Maize accuracy 90.9% (also rice 96.7% reported) | Ensemble is effective across crops | Improve with IoT device setup | 2023 |