1. Introduction

African swine fever (ASF) has significantly impacted the global swine industry in recent years [

1]. The lack of effective vaccines or treatments for ASF has underscored the critical need for robust biosecurity management [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Despite the high stakes, many pig farms continue to rely on manual, paper-based records for personnel tracking. This practice is not only prone to error but also hinders the transition toward comprehensive digital management systems. In response to the 2018 ASF outbreak, Wang Q et al. outlined biosecurity measures, including the implementation of enclosed management on large-scale farms [

6], and strict exit-only policies for personnel in affected regions [

7].

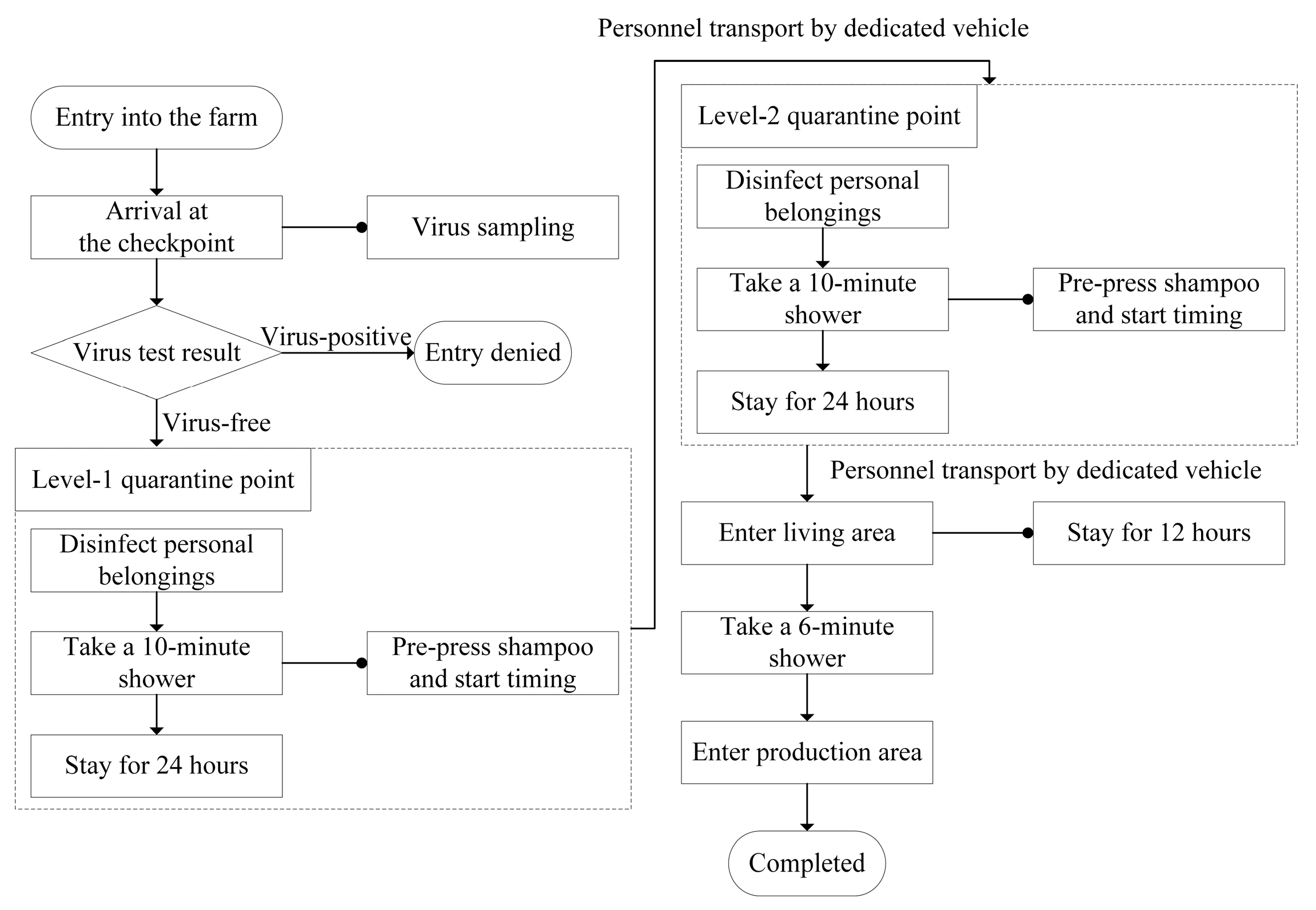

Taking the swine production base of DABEINONG GROUP (DBN) located in Zhaoqing, Guangdong as an example, its personnel entry management follows a standardized procedure, as illustrated in

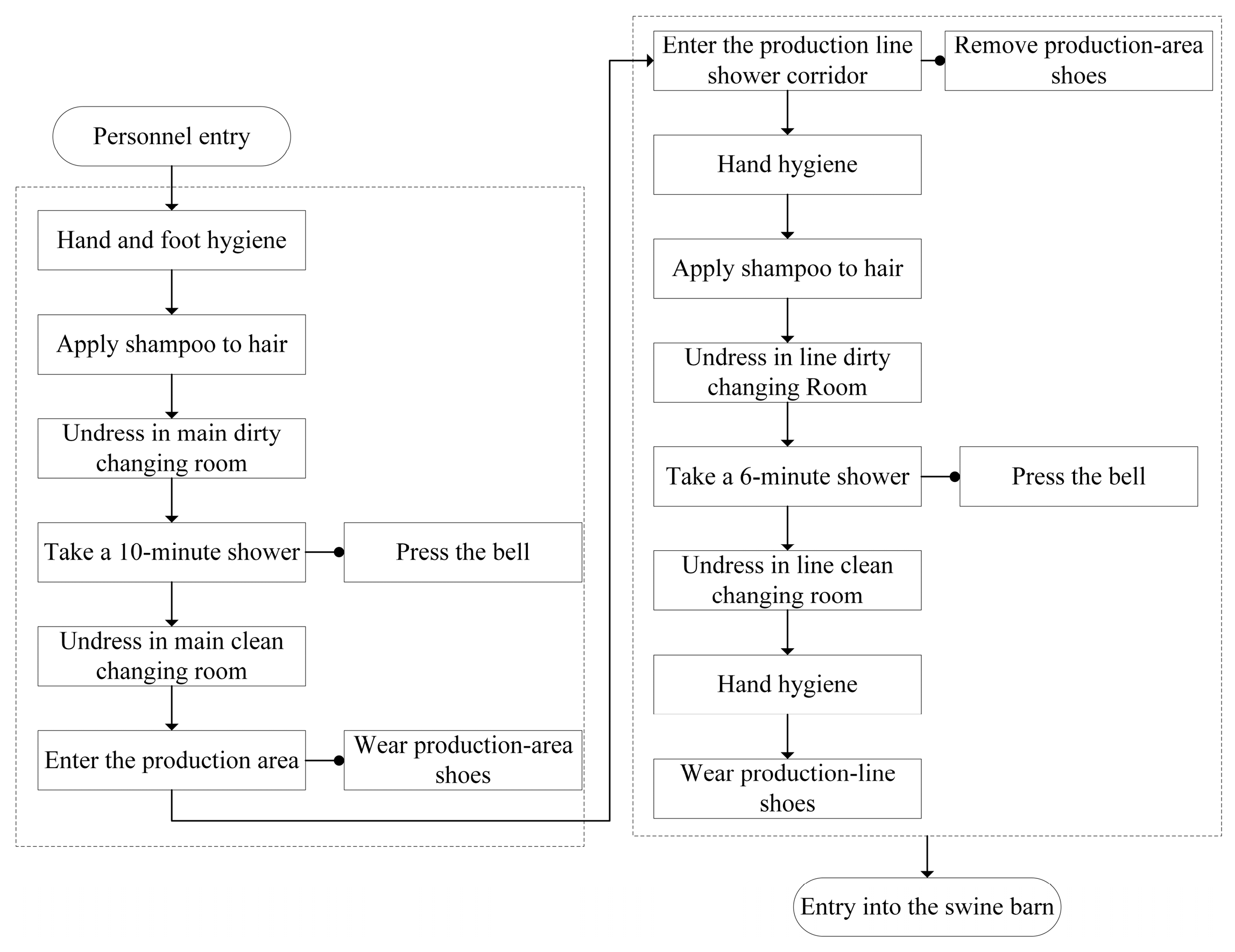

Figure 1. The swine production base of WENS GROUP(WENS) has a more detailed and stringent procedure for personnel entering the pig houses from the living quarters, as illustrated in

Figure 2 [

8].

In recent years, the application of digital technologies in pig farming has been a significant area of research. Li B. M. et al. reviewed advancements in intelligent equipment and information technologies for livestock and poultry farming [

9]. They noted that digitization in pig housing primarily relies on IoT technologies to collect, analyze, and predict environmental conditions and feed volumes, thereby reducing operational costs and improving efficiency [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Sungju Lee et al. applied computer vision techniques to monitor pig growth [

15,

16]. Their system utilizes embedded devices for computationally efficient visual object detection; the collected data is then transmitted to a cloud-based IoT platform for further processing, analysis, and generation of early warnings [

17]. The overarching goal of such technologies is to reduce labor workload and enhance production efficiency [

18].

Concurrently, research has specifically targeted biosecurity control systems. Liu Zhanqi et al. developed a visual recognition algorithm using YOLO-series and ResNet models to detect non-compliance with workwear regulations, thereby enhancing biosecurity management [

19,

20,

21]. In another approach, Zhang Zhiyong et al. developed a PLC-based smart shower management system. This system uses magnetically locked doors, monitors water flow and shower duration to enforce proper showering procedures during transitions from dirty to clean zones, ensuring biosecurity compliance [

22]. Nicholas J. Black et al. investigated the relationship between personnel movement in sow facilities and the number of piglets weaned per sow using an internal monitoring system [

23]. The system used beacon sensors to track personnel movement and dwell time in individual pens [

24]. Data were transmitted to a central controller and aggregated weekly. Their results showed that higher movement frequency between pens was associated with fewer piglets weaned per sow and reduced biosecurity [

25,

26,

27]. Sykes Abagael L. used machine learning to analyze livestock demographic data from cattle farms and historical disease records from 139 swine herds, demonstrating that staff numbers, turnover, surrounding building density, and external contacts significantly influenced disease outbreak risk [

28,

29].

Despite these advancements, IoT applications for farm personnel biosecurity management remain at a relatively primitive stage. Both Wens and DBN groups have established standardized procedures for personnel entry management, yet these processes still rely on manual recording and lack IoT integration. The PLC-based intelligent shower system proposed by Zhang Zhiyong et al. enhances procedural compliance but lacks IoT connectivity for comprehensive personnel movement records [

22]. In contrast, the IoT-based access control system developed by Lin Junqiang et al. enables personnel tracking but operates without a cloud data platform, nor has it been deployed in pig farm environments [

30]. Similarly, the workwear recognition algorithm developed by Liu Zhanqi has not been widely deployed in large-scale farms because of inadequate real-time performance and excessive computational requirements [

19]. Consequently, critical parameters such as shower duration and isolation times are still predominantly recorded manually, increasing both labor costs and the risk of human error. Furthermore, the movements of external personnel, technical staff, and managers remain difficult to monitor, thereby creating persistent biosecurity vulnerabilities. However, none of the existing systems provide an integrated solution that simultaneously supports biometric identification, cross-terminal synchronization, and cloud-level personnel movement supervision within swine-farm biosecurity workflows.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a digital personnel management system that supports large-scale deployment and ensures stable operation under poor network conditions. It captures personnel movement via fingerprint modules, calculates shower duration based on the interval between check-ins at different changing rooms, and integrates data through local controllers and a cloud platform. In addition, the system’s performance was evaluated under high-load CAN and MQTT communication conditions. The proposed system aims to reduce manual workload and errors, improves the precision and transparency of biosecurity management, and offers an efficient, scalable, and sustainable solution for large-scale swine farming enterprises.

2. Materials and Methods

To achieve comprehensive and accurate tracking of personnel movement within swine farms, a three-tier architecture was developed. This architecture consists of STM32-based distributed identification terminals, Qt-based local central controllers and a Python-based cloud-based data platform. This integrated architecture acquires personnel information and thereby enables comprehensive digital management. The system utilizes a local database on the central controller for immediate data storage and a centralized master database on a remote cloud server for long-term data retention. Personnel information includes personnel attendance records, fingerprint templates, shower duration, and personnel movement records. At the same time, it prevents biosecurity breaches caused by personnel errors.

2.1. The Architecture of the System

The digital personnel management system comprises three core components: integrates distributed identification terminals, local central controllers, and a cloud-based data platform. The shower corridor consists of a dirty-area changing room, a shower room, and a clean-area changing room. Terminals are installed in both changing rooms, and the central controller is located in the clean area changing-room. Terminals are interconnected and communicate with the central controller via a robust CAN bus network. The local central controllers, in turn, communicate with the cloud-based data platform using the MQTT protocol. The terminals acquire attendance records through fingerprint identification; the central controller derives shower duration from these records, and the cloud platform computes personnel movement trajectories.

The system supported the following key functions:

- (1)

Distributed Identification Terminal: Deployed in the changing-room, these terminals perform personnel identification and record personnel attendance.

- (2)

Local Central Controller: This unit acts as a local data aggregator within each shower corridor. It collects personnel attendance records and fingerprint templates from all connected terminals via the CAN bus. The data is temporarily stored in a local database, processed locally for analysis and visualization, and is purged only after successful synchronization with the cloud platform, ensuring data integrity even during network outages.

- (3)

Data Platform: This platform receives data from central controllers via MQTT. It processes this information and serves as the permanent repository for personnel information enabling long-term analysis.

Figure 3 illustrates the system architecture.

2.2. Design of Distributed Identification Terminal

The terminal uses the STM32F103 series (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) as its control core and incorporates peripheral circuits for power supply, personnel identification, human–machine interaction, and data communication. These components form a comprehensive and well-structured hardware platform that provides the foundation for subsequent software control and system implementation.

The power supply module uses an external 220 V AC input to accommodate the future addition of temperature control for changing-room environments. It is designed with AC–DC conversion, voltage regulation, and filtering functions. At its core is the LH10-23B05R2 power conversion module (Mornsun Guangzhou Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China), which works together with a JK250-120U fuse (ShenZhen JinRui Electronic Material Co.,Ltd, Shenzhen, China) to ensure electrical safety for the control box. The power conversion and regulation circuit is illustrated in

Figure 4. The first stage converts 220 V AC to 5 V DC, while the second stage provides voltage regulation as well as electrostatic and surge protection.

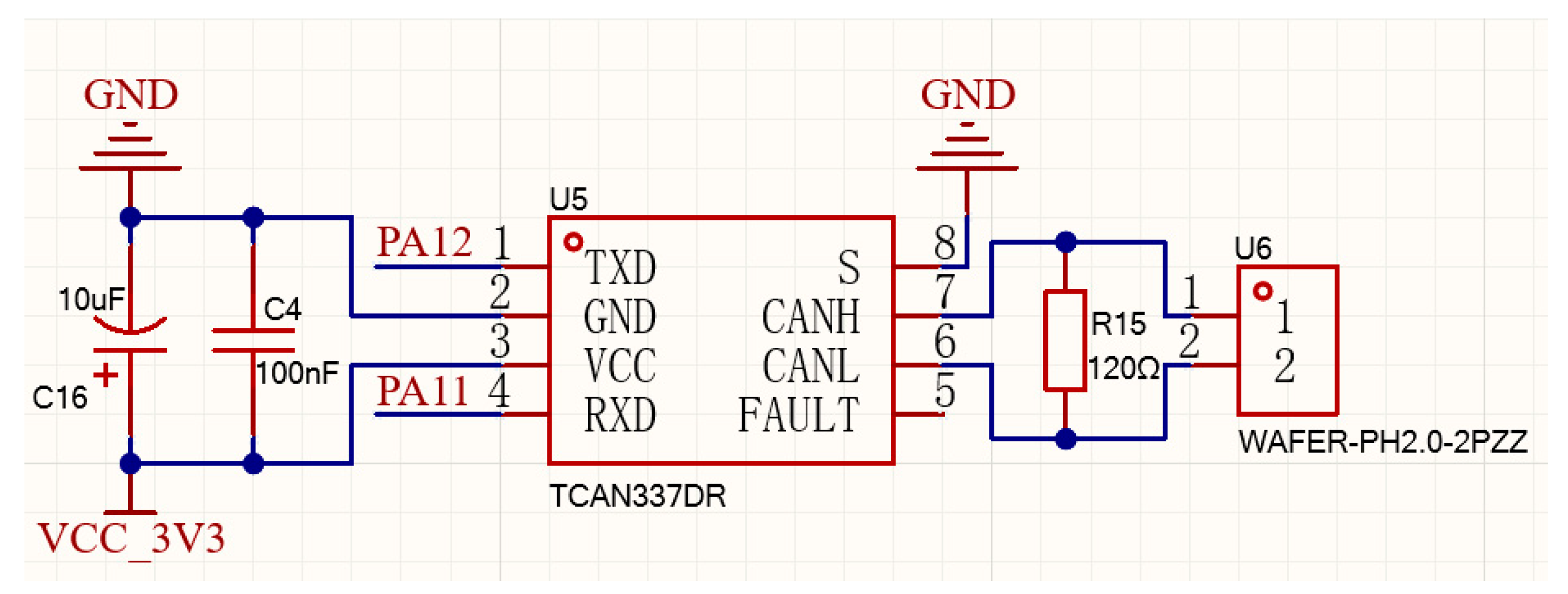

In this system, the clean changing-room terminal and the central controller are installed in the clean changing room, while the dirty changing-room terminal is placed in the dirty changing room. The distance between the two terminals is approximately 2–10 m. The system is planned to integrate multiple shower-function sub-controllers in subsequent deployments. In multi-device communication scenarios, the CAN bus offers higher stability and overall performance compared with RS485 and other fieldbus options. So, the data communication circuit adopts a CAN bus, which offers support for multiple devices, high reliability, strong real-time performance, and good noise immunity, though it has certain limitations when transmitting large volumes of data. The circuit is built around the TCAN337DR transceiver (Texas Instruments Incorporated, Dallas, TX, USA), which can operate reliably in harsh environments and supports the CAN FD protocol, providing dependable support for future fingerprint-data transmission. The use of a CAN bus network also enables the expansion of additional shower terminal devices and facilitates the development of a custom CAN communication protocol to address high-volume data transfer. The data communication circuit is shown in

Figure 5.

A custom enclosure was designed to house the terminal’s electronics and provide a basic Human–Machine Interface (HMI). The enclosure features mounting points for the circuit board, a cutout for an OLED display on its top surface, and four spring-loaded push buttons for user interaction. The design of the control box is illustrated in

Figure 6.

For personnel identification and attendance records, the system employed an AS608 fingerprint module (Hangzhou Synochip Data Security Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China). The module supported fingerprint identification and enrollment [

31]. Finger contact was detected via the WAK signal pin, while the Tx and Rx pins facilitated USART-based communication with external devices. It included a 72 KB image buffer and a 512-byte feature template buffer, where features were generated from processed fingerprint image data. The fingerprint module captured fingerprint images through integrated detection and collection circuitry [

32].The fingerprint enrollment process generates a feature template and stores it in the module’s database, associating it with a unique ID. Verification is performed by comparing a newly captured template against all reference templates stored in the database. Both processes were carried out via USART serial communication between the terminal and the fingerprint module. When a terminal completes fingerprint enrollment, it sends the feature templates along with the timestamp and location to the central controller via the CAN bus. When a terminal completes verification, it sends the personnel ID together with the timestamp and location to the central controller via the CAN bus.

To ensure consistent fingerprint data across the facility, the system supported the cross-terminal synchronization of fingerprint templates. Due to the high storage and transmission demands of raw fingerprint images, the system used mathematically derived feature templates as compact and transferable biometric representations for enrollment and verification. When a fingerprint was enrolled at a terminal, the generated feature template was transmitted to the central controller via the CAN bus for permanent storage. For cross-terminal registration, the new terminal requests the user’s template from the central controller, which then transmits it over the CAN bus. This architecture allows for seamless biometric access across a distributed system. All data synchronization operations between terminals and the central unit rely on CAN bus communication [

33,

34].

The feature extraction process is illustrated in

Figure 7.

2.3. Software Design of the Central Controller

The central controller functions as the coordination and data-management hub for all distributed identification terminals. Its primary role is to overcome the limited storage, computing capacity, and user-interaction capabilities of embedded devices by providing centralized data aggregation, cross-device synchronization, and on-site visualization. The HMI software (version 1.1) was developed in C++ using the Qt 6.3 GUI framework, a cross-platform toolkit compatible with both desktop and embedded systems [

35]. The software interface is illustrated in

Figure 8.

To ensure responsiveness during high-frequency communication, the software employs a multi-threaded and decoupled design. In this architecture, each major sub-thread operates independently and communicates through message queues.

The CAN communication thread is responsible for receiving raw CAN frames, validating CRC, reconstructing multi-frame packets, and forwarding them to the database thread.

The database thread handles transactional batch writes to minimize I/O contention. This thread ensures that CAN and MQTT data are inserted atomically, preventing partial or inconsistent records.

The MQTT communication thread manages cloud connectivity, message publication, and retrieval of policy or template updates. All transmitted data is formatted in JSON, and queuing mechanisms decouple local processing from network delays.

The main thread is dedicated exclusively to rendering user-interface elements and processing operator input. It does not directly handle I/O, preventing blocking during high-load conditions. The separation of communication, storage, and interface logic is essential for maintaining predictable performance under varying load conditions, especially when multiple terminals transmit high-frequency data simultaneously.

To maintain data integrity and minimize bandwidth usage, the central controller stores all data in a local SQLite database containing three logically independent tables: AttendanceRecords, FingerprintTemplates, and DeviceStatusLogs. The MQTT transmission layer used JSON payloads—a lightweight, hierarchical structure enabling simultaneous transmission of metadata and core data [

36].

All data received by the central controller from the terminals is stored in a local SQLite database. The database thread calculates each individual’s shower duration based on the attendance data stored in the AttendanceRecords table and writes the results back into the same table. The controller then processes the data according to predefined instructions and provides it to the main thread for display.

After 9 p.m., the system begins continuously monitoring network status, and once a stable connection is detected, it uploads the data from the local SQLite database to the cloud platform. To ensure the uniformity of personnel fingerprint templates and to reduce the need for repeated fingerprint enrollment, the central controller implements a template-distribution mechanism. It ensures that when a user registers a fingerprint at one terminal, the template is propagated to all relevant terminals via the controller.

The central controller performs three core functions:

- (1)

Multi-terminal coordination over CAN.

It manages the exchange of personnel movement, fingerprint templates, and device-status frames across all terminals. A dedicated communication layer handles frame parsing, multi-frame reassembly, and error checking to ensure reliable message delivery in noisy electrical environments typical of livestock facilities.

- (2)

Local buffering and data integrity assurance.

Because network availability on farms is often unstable, the central controller maintains a local database that temporarily stores attendance records, equipment status reports, and biometric templates. Data are synchronized with the cloud platform only after connectivity is restored. This store-and-forward mechanism prevents data loss and ensures consistency across terminals.

- (3)

Real-time monitoring and visualization.

The controller provides a graphical interface for displaying personnel entry events, device states, and communication diagnostics. Operators can review recent activity, inspect abnormal events, or initiate manual synchronization. This interface also enables per-site configuration such as terminal registration and zoning rules.

2.4. Design of Data Transmission Protocol

To ensure the scalability and long-term reliability of the system, a CAN bus is adopted as the communication method. However, the CAN bus has the inherent limitation of supporting only small data payloads. To address this constraint, a custom communication protocol is developed on top of the CAN bus to enhance data transmission capability.

Communication protocols serve as standardized frameworks for message exchange between data acquisition endpoints and collection systems. In personnel movement management, they play a crucial role by defining structured data encapsulation. Custom protocols optimize parsing efficiency by tailoring communication structures to specific operational needs [

37].

The system used a custom 8-byte payload protocol over the CAN bus to facilitate communication between the terminals and the central unit. The data frame format is illustrated in

Figure 9. To ensure data accuracy, a CRC check frame was appended after the transmission of each data frame to verify data integrity. The CRC check frame was generated by performing a bitwise inversion of the original data frame [

38].

Due to the complexity of fingerprint feature template transfers, the system used a multi-frame transmission protocol. The data format structure is illustrated in

Figure 10.

The Preliminary Frame, ID Frame, Data Initiation Frame, and Data Termination Frame follow the standard format. In Multiple Data Frames, all eight bytes are dedicated to payload data. A complete data transmission consists of 840 frames. For fingerprint data, only a fingerprint-specific CRC check frame needs to be appended at the end. The fingerprint CRC check frame is generated by performing a bitwise inversion of the corresponding ID frame content.

The fingerprint feature template payload inherently includes USART start and end field, which are preserved intact by the central controller without parsing. The controller buffers all received frames in sequence and forwards them over the CAN network in their original order. The terminal then reconstructs the complete template by reassembling the frames sequentially.

2.5. Design of the Data Platform

The data platform integrates the equipment status data, attendance records, and shower duration collected from multiple distributed local central controllers. The platform is deployed on Tencent Cloud with the following configuration: dual-core CPU, 2 GB RAM, 50 GB storage, and 3 Mbps bandwidth. The operating system is Ubuntu.

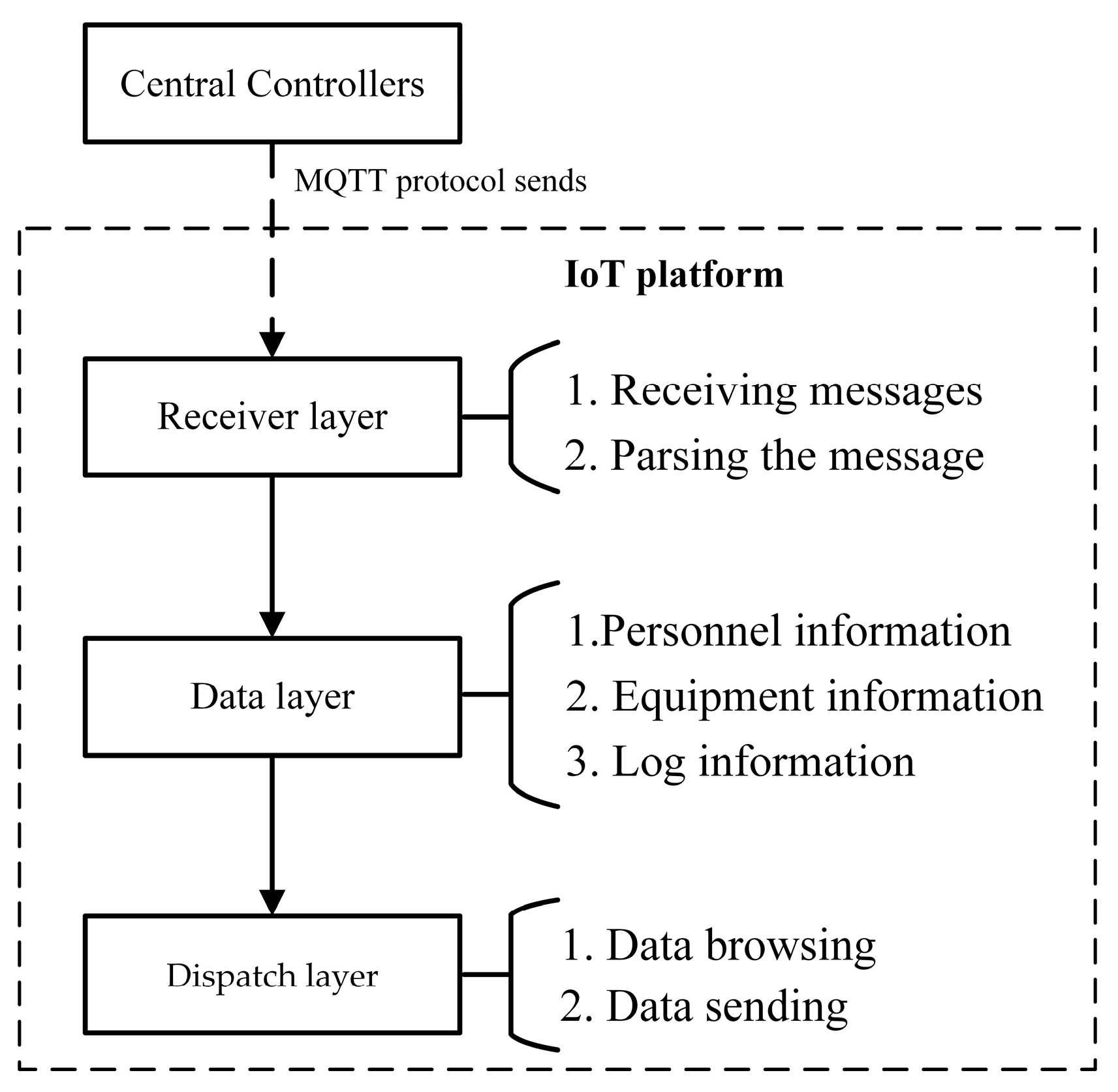

The data platform comprises three components: the reception layer, the data layer, and the dispatch layer [

39]. The reception layer collects and parses JSON-formatted message data uploaded by central controllers via the MQTT protocol. The data layer stores the equipment operational status and attendance data and provides query interfaces. The dispatch layer receives commands from the central controller via MQTT and retrieves the corresponding data from the data layer to send back to the controller.

The reception layer and the dispatch layer, developed in Python 3.12.3, ran as a persistent system service to ensure stable, long-term operation. The data layer employed SQLite databases with dedicated tables for attendance records and fingerprint templates. Using the complete attendance records maintained in the data layer, the system reconstructs personnel movement trajectories and commits the resulting records to the database.

Figure 11 illustrates the data platform’s layered architecture and its desktop interface.

2.6. Test Metrics

For this system, the accuracy of fingerprint recognition is critical, as it directly determines whether the raw attendance records are correctly captured. In addition, the communication performance of both the CAN bus and the MQTT protocol is essential, as it affects the reliability of system operation and the integrity of personnel information recording.

2.6.1. Fingerprint Recognition Accuracy Metrics

The accuracy of the fingerprint recognition system is a critical performance indicator, as it directly impacts the reliability of personnel attendance records. This was quantified using the success rate, calculated with Equation (1). A higher success rate indicates superior recognition performance.

where

—Success rate (%);

—Number of successful recognition attempts;

—Total number of recognition attempts.

2.6.2. CAN Bus Communication Performance Metrics

The system requires frequent communication between multiple terminals and the central controller over the CAN bus. The performance of this communication was evaluated based on two primary criteria:

- (1)

The reception performance of the central controller when terminals transmit multi-frame data, focusing on data integrity and processing latency;

- (2)

The reception accuracy at the terminals when the central controller transmits multi-frame data, focusing on data integrity and response latency.

Data integrity was measured using the Packet Loss Rate (

PLR), calculated as shown in Equation (2). Latency was measured as the time difference between transmission and reception, as defined in Equation (3).

where

—Packet loss rate (%);

—Total number of data frames transmitted;

—Total number of data frames successfully received.

where

—Response latency ();

—Data transmission timestamp;

—Data reception timestamp.

2.6.3. MQTT-Based Network Communication Performance Metrics

Personnel management across the enterprise relies on the central controller to both upload and retrieve data from the cloud-based IoT platform. Therefore, it is essential to verify whether the cloud IoT platform meets the system’s operational requirements. The performance of this network communication was evaluated based on the following metrics:

- (1)

Response time for connection initialization.

- (2)

Packet loss rate, response time, and processing latency during data uploads from the central controller to the cloud.

- (3)

Packet loss rate, response time, and processing latency during data retrieval requests initiated by the central controller.

2.7. Test Procedures

The experiment was conducted under normal indoor conditions, ensuring that the fingerprint modules were clean, the CAN bus connection distance was within 2–10 m, and the central controller’s network was operating smoothly.

2.7.1. Fingerprint Recognition and Template Transmission Test

A typical shower corridor in a swine farm usually accommodates ten employees. This test evaluated both the biometric accuracy of the fingerprint module and the reliability of the template synchronization process.

Fingerprint recognition test was conducted collaboratively by the terminal and the central controller. For this test, ten participants were enrolled in the system, each with a unique ID and two registered fingerprint templates (20 templates total). Enrollment was conducted under controlled conditions, ensuring participants’ fingers and the sensor surface were clean.

The evaluation protocol consisted of two stages. The first stage, single-user continuous authentication test, involved one participant completing 20 consecutive identification attempts, alternating between their two enrolled templates. The second stage, a multi-user queued authentication test, required all ten participants to perform identification sequentially, each using either of their two templates for verification. These stages assessed the accuracy and robustness of the fingerprint recognition system under both repeated single-user and multi-user conditions.

For the template transmission test, two terminals (A and B) were connected to the central controller. Ten fingerprint templates were enrolled on Terminal A. These templates were then transmitted to the central controller and subsequently forwarded to Terminal B. The successful reception and correctness of the templates on Terminal B were verified. This entire cycle was repeated five times to assess the stability and consistency of the data transfer mechanism.

2.7.2. CAN Bus Communication Performance Test

This experiment was designed to stress-test the CAN bus communication under high-load conditions, simulating the transfer of personnel records and fingerprint templates. In this experiment, the terminals transmitted dummy data packets—equivalent in size to actual fingerprint templates—to the central controller at varying frequencies and numbers of transmission attempts. To accommodate high data volumes received within short timeframes, the central controller employed a signal–slot mechanism to route CAN thread data to an SQL thread for storage. Transactional batch processing was used for SQLite database operations to ensure data integrity and efficiency.

The test configurations included the following parameters:

- (1)

Number of transmission attempts: 500, 1000, 2000, and 3000.

- (2)

Transmission frequencies: 5 Hz, 10 Hz, 20 Hz, 50 Hz, and 100 Hz.

The 5 Hz transmission rate reflects real operational conditions, where multiple terminals periodically report status or identification events. Higher frequencies (50–100 Hz) were intentionally used as stress-testing conditions to evaluate the system’s robustness under dense data loads or multi-terminal simultaneous communication—scenarios that may occur in large-scale farms. Each combination of parameters was tested in three independent repetitions to evaluate the system’s reliability and performance under different load conditions.

2.7.3. MQTT Network Communication Performance Test

The consolidation of personnel movement records across multiple pig farms and the enforcement of biosecurity protocols depended on stable network transmission. Therefore, comprehensive network communication testing was conducted using three designed protocols.

The first experiment evaluated data response time under single-link connectivity. Response time was defined as the interval between transmission initiation and acknowledgment reception at the central controller. In this test, the central controller transmitted 1085 initialization signals to the cloud IoT platform.

The second experiment assessed the transmission performance of the central controller under high-frequency conditions, simulating scenarios in which multiple records were transmitted simultaneously. A total of 1200 attendance records were transmitted from the central controller to the cloud IoT platform under various transmission frequencies and attempt counts. All transmitted data were stored on the cloud IoT platform via transactional batch processing. The test parameters were set as follows: (1) transmission attempts: 10, 20, 50, and 100; (2) transmission frequencies: 5 Hz, 10 Hz, 50 Hz, and 100 Hz. Each parameter combination was tested over three cycles. The central controller’s response time and the cloud platform’s processing time were measured to evaluate system performance.

Finally, the third experiment evaluated the request performance of the central controller when retrieving data from the cloud, simulating scenarios involving simultaneous record requests. In this test, the central controller transmitted 100 data requests at four different frequencies: 5 Hz, 10 Hz, 50 Hz, and 100 Hz. Response data were stored locally on the central controller via transactional batch processing. Each frequency was tested across three cycles. System performance was assessed by measuring cloud processing time, Qt response time, and Qt processing time for specific data requests initiated by the central controller.

These three experiments were designed to reflect both the typical operational conditions and the stress conditions encountered in large-scale swine farms. Under normal usage, personnel-entry events are generated at low frequency, and the central controller transmits sparse attendance records to the cloud. Therefore, low-frequency transmission tests (e.g., 5–10 Hz) were included to verify that the system maintains stable, real-time operation in everyday farm environments. Similarly, the request-retrieval experiment reflects situations in which multiple controllers query the cloud platform concurrently, such as during centralized auditing, large-scale personnel scheduling, or system-wide policy updates. Evaluating cloud-to-edge request performance under different frequencies ensures that the platform can support enterprise-level supervision without compromising response time.

3. Results

3.1. Fingerprint Recognition and Template Transmission Performance

The test results are summarized in

Table 1. In the initial test on a single terminal (Controller A), 210 verification attempts were performed, which included 20 failures, yielding a recognition success rate of 90.5%. The reliability of the cross-terminal template synchronization was then evaluated. All 50 template transmissions from Controller A to Controller B were completed successfully, achieving a 100% transmission rate. Of these, 46 templates were correctly processed and stored on Terminal B, resulting in a functional recording success rate of 92%. Across all tests, a total of 256 verification attempts were conducted, with 236 successful outcomes, corresponding to an overall system verification success rate of 91.4%.

Qualitative analysis revealed that the majority of recognition failures were attributed to significant positional deviations of the finger on the sensor between the enrollment and verification stages. Crucially, no false positive identifications (i.e., User misidentifications) were observed during the tests, ensuring that user-specific activities were logged with high integrity.

A qualitative review of failure cases indicates that most mismatches were caused by finger placement inconsistencies between enrollment and verification (e.g., shifts in angle or contact area). Importantly, no false positive identifications were observed, ensuring the integrity of user-specific activity logs.

3.2. CAN Bus Communication Performance

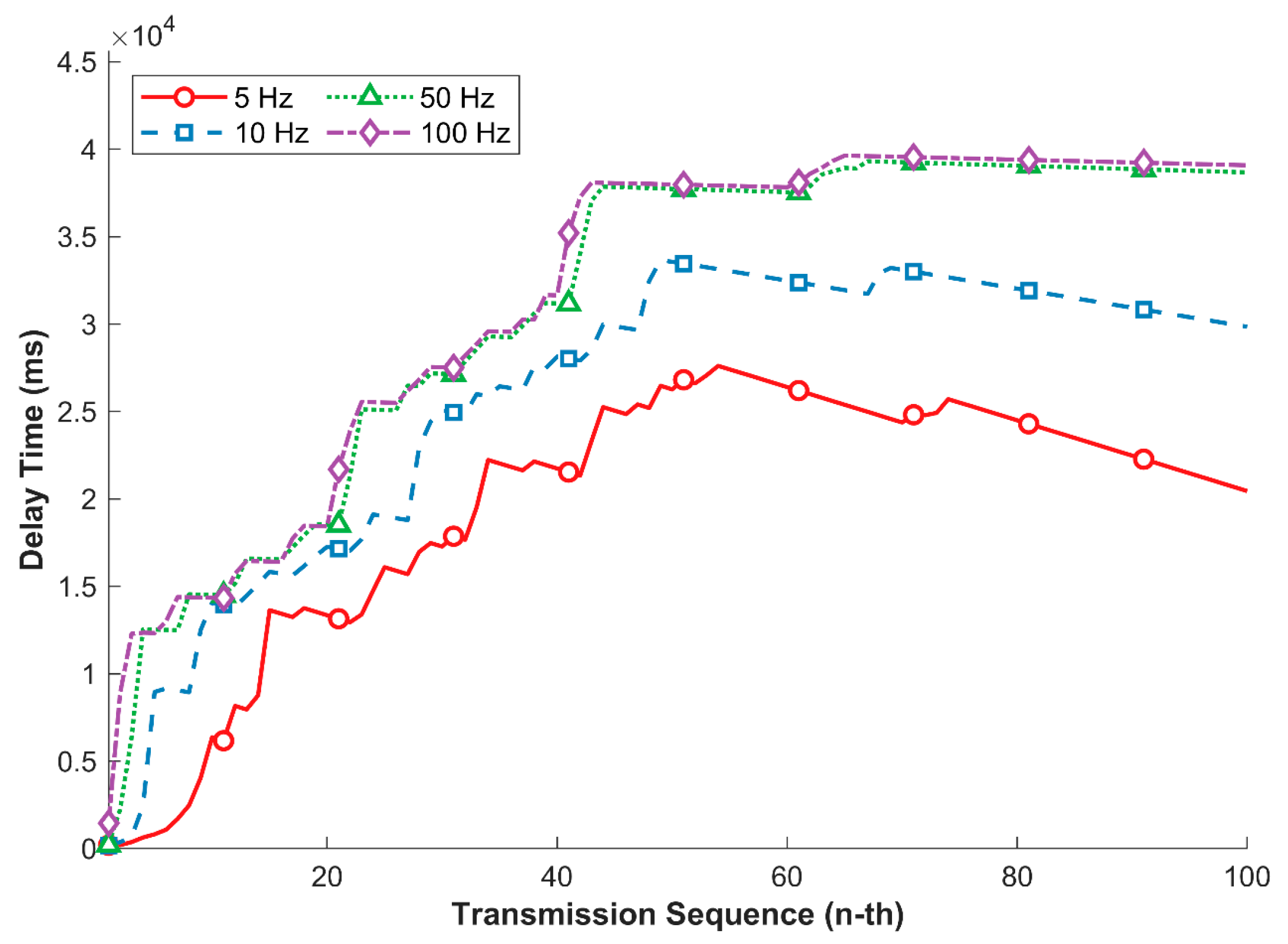

The test results are summarized in

Figure 12. This test evaluated the performance of the central controller when receiving high-frequency data streams over the CAN bus. Across all test configurations, no packet loss was observed, indicating perfect data integrity at the transport layer.

The mean processing delay for each data packet at the central controller was 99.96 ms. However, the stability of this processing delay, measured by its standard deviation, was highly dependent on the transmission frequency. At a low frequency of 5 Hz, the standard deviation remained consistently below 3 ms, indicating stable and predictable performance. In contrast, at higher frequencies (10 Hz, 50 Hz, and 100 Hz), the standard deviation exhibited significant fluctuations, reaching values as high as 30 ms. This suggests that while the system can handle high data rates without data loss, the processing latency becomes less predictable under heavy load.

These results indicate that while the system is capable of sustaining high-frequency CAN traffic without data loss, latency jitter grows substantially under heavy load, revealing a potential performance limit of the embedded controller’s processing architecture.

3.3. MQTT-Based Network Communication Performance

3.3.1. Data Upload Performance to the Cloud Platform

The network performance was first evaluated for connection establishment and then under high-frequency data upload conditions. In the connection latency test, 1085 initialization signals were sent to the cloud platform. The mean response time was 21.95

with a standard deviation of 4.25 ms. The maximum and minimum response times were 70 ms and 14 ms, respectively, indicating a stable and responsive connection suitable for practical operations.

The results of the high-frequency upload tests are detailed in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14.

Figure 13 illustrates that under the condition of 100 fixed transmission attempts, the total processing time on the central controller (Qt application) increased as more requests were made sequentially. In stark contrast, the cloud-side processing time remained stable and efficient across all test conditions. The peak average processing time per record on the cloud was only 70.7 ms, with a standard deviation not exceeding 13.75 ms. No packet loss was recorded during any upload tests. These findings indicate that the performance bottleneck during large-scale uploads stems from the limited processing capacity of the local central controller and the MQTT protocol service, rather than the cloud platform.

These results suggest that the performance bottleneck during large-scale uploads arises primarily from the local controller’s processing capacity and the MQTT protocol service, rather than from cloud-side limitations.

3.3.2. Data Retrieval Performance from Cloud-Based IoT Platform

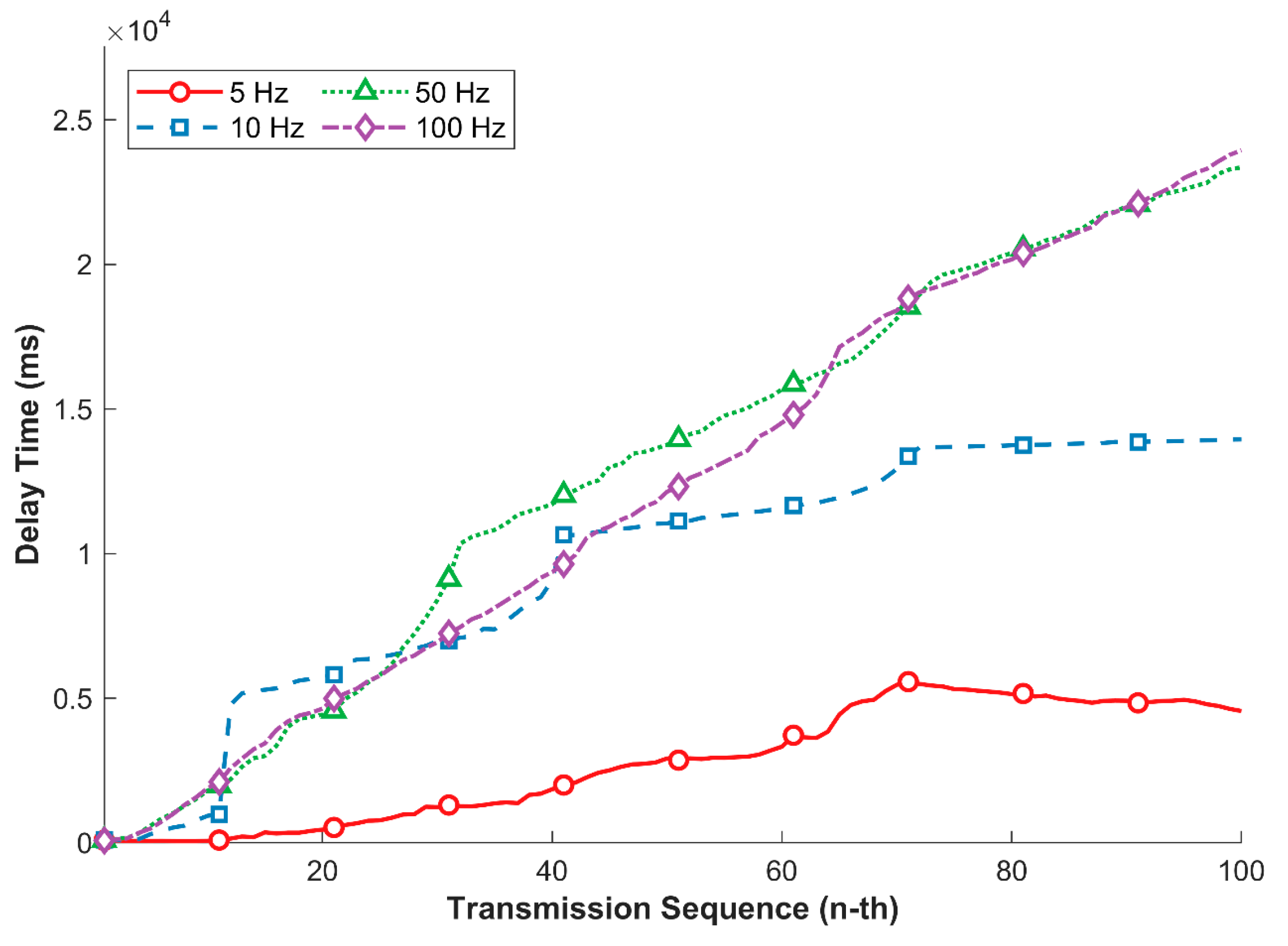

The performance of data retrieval from the cloud is presented in

Figure 15 and

Table 2. Similarly to the upload tests, the cumulative response time on the central controller (Qt) increased as more requests were made sequentially (

Figure 15). At higher frequencies (10 Hz, 50 Hz, and 100 Hz), the delay accumulated rapidly, reaching approximately 10,000 ms after only 41 requests.

Table 2 provides a statistical summary of the processing latencies. The cloud processing time remained consistently low and stable across all frequencies, with a peak average of 27.3 ms and a maximum standard deviation of 5.9 ms. Conversely, the processing time on the local controller, while averaging between 162 ms and 189 ms, showed significant instability. Notably, at 10 Hz, the standard deviation reached an exceptionally high 605.1 ms, indicating the presence of sporadic, high-latency events. No packet loss was observed during data retrieval. This highlights a potential performance issue on the client side during intensive data retrieval, suggesting that the controller’s software architecture is the primary limiting factor.

No packet loss occurred during retrieval tests, confirming the reliability of the network channel. However, the highly unstable controller-side latency under heavy load highlights a software-architecture bottleneck in the local controller, particularly within its event-handling and MQTT processing routines.

4. Discussion

The digital personnel management system developed in this study demonstrated solid performance in enhancing biosecurity within swine farms, with key strengths in personnel identification, data transmission reliability, and cross-device synchronization. Nevertheless, a detailed analysis of the test results also highlights several limitations that must be considered for practical deployment and further system optimization.

4.1. Performance Insights

The fingerprint recognition accuracy of 90.5% for an individual terminal and 92% for cross-device synchronization highlights the system’s effectiveness in biometric identification. These results are important for ensuring secure and accurate personnel movement tracking, which is a key aspect of biosecurity management. However, the success rate could be further improved by addressing potential issues, such as variations in fingerprint positioning during verification, which caused a small number of failed attempts. Future versions of the system could integrate advanced fingerprint enhancement algorithms or multi-modal biometric systems to reduce these errors and enhance user experience.

The communication reliability between the terminal and the central controller was assessed with a processing delay of 99.96 ms and no packet loss at a 5 Hz transmission frequency. This performance is well within acceptable limits for biosecurity applications, where timely data exchange is essential. However, as the transmission frequency increased (e.g., to 50 Hz or 100 Hz), the delay exhibited significant fluctuations, indicating that the system’s performance may degrade under high-frequency conditions. A typical shower corridor in a swine farm usually accommodates ten employees. Experimental results indicate that at 5 Hz, the system exhibits relatively low latency. This suggests that while the system is reliable under normal operating conditions, challenges may arise when handling large data volumes, particularly in larger farm environments or during peak operation periods.

The MQTT protocol communication between the central controller and the cloud platform demonstrated stable performance under typical conditions, with a peak average cloud processing time of 70.7 ms. Despite this, high-frequency and high-volume data transmission resulted in notable latency, with the central controller’s processing delay peaking at 188.6 ms. These findings underline the importance of optimizing the communication channels to ensure scalability as farm operations expand. While cloud platforms offer significant advantages in data storage and accessibility, their performance may be affected by network congestion or high-frequency transmission demands.

4.2. Limitations of the Current System

Despite the promising performance, the current system faces several limitations that need to be addressed for broader deployment:

- (1)

Client-Side Processing Bottleneck: While the cloud IoT platform can handle normal transmission loads, it experiences significant delays at higher frequencies. The peak processing delay observed at 100 Hz is above the acceptable threshold for real-time applications. This limitation is likely due to both network latency and the cloud’s processing capacity, which may struggle with high-frequency data streams.

- (2)

Scalability in Multi-site Operations: As more farms and production lines are integrated into the system, managing data flow between locations becomes increasingly complex. Although the current system supports cross-farm data transmission, the reliability and speed of these transmissions may degrade when multiple central controllers transmit data simultaneously.

4.3. Future Optimization Directions

To overcome these limitations and enhance the system’s overall performance, several optimization strategies should be considered:

- (1)

Batch Data Upload and Edge Computing: One potential solution to reduce high-frequency transmission delays is implementing batch data uploads. Instead of transmitting real-time data continuously, the system could temporarily buffer the data at local devices (e.g., attendance-environmental control terminals) and transmit it in bulk during low-traffic periods. This approach would reduce the load on both local and cloud systems, ensuring more stable performance.

- (2)

Enhanced Fingerprint Recognition Algorithms: To improve biometric recognition accuracy, especially under challenging conditions (e.g., poor fingerprint placement), advanced machine learning algorithms could be integrated into the system. These algorithms could dynamically adapt to different user behaviors and environmental conditions, increasing the success rate and reducing verification failures.

- (3)

Real-time Monitoring and Anomaly Detection: To further bolster the system’s biosecurity capabilities, integrating real-time anomaly detection based on personnel movement trajectory could enhance early-warning capabilities. Machine learning models could be deployed to detect unusual behavior or violations of biosecurity protocols, such as unauthorized personnel entering sensitive areas, and trigger immediate alerts for corrective action.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a digital personnel management system designed specifically for the changing-room environment that forms the core of biosecurity workflows in modern swine farms. The system integrates distributed biometric identification terminals, a local central controller, and a cloud-based IoT platform to provide reliable identity verification, cross-device fingerprint template synchronization, and continuous data availability under unstable network conditions.

Experimental evaluation confirms that the system achieves high fingerprint recognition accuracy, lossless multi-frame data transmission over CAN, and stable end-to-end communication over MQTT. These results demonstrate that the proposed architecture is technically feasible and offers a practical digital alternative to manual personnel movement records, providing improved traceability and enhanced biosecurity supervision for large-scale swine enterprises.

At the same time, the study identifies several limitations, including performance degradation under high-frequency communication loads and scalability challenges in multi-farm deployments. These findings suggest that further optimization—particularly in transmission strategies, biometric recognition algorithms, and intelligent behavioral monitoring—will be essential to fully realize the system’s potential in large, distributed farm networks.