Exploring the Impact of Affective Pedagogical Agents: Enhancing Emotional Engagement in Higher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Animated Pedagogical Agents

1.2. Cognitive Feedback

1.3. Affective Feedback

1.4. Wrapping Up

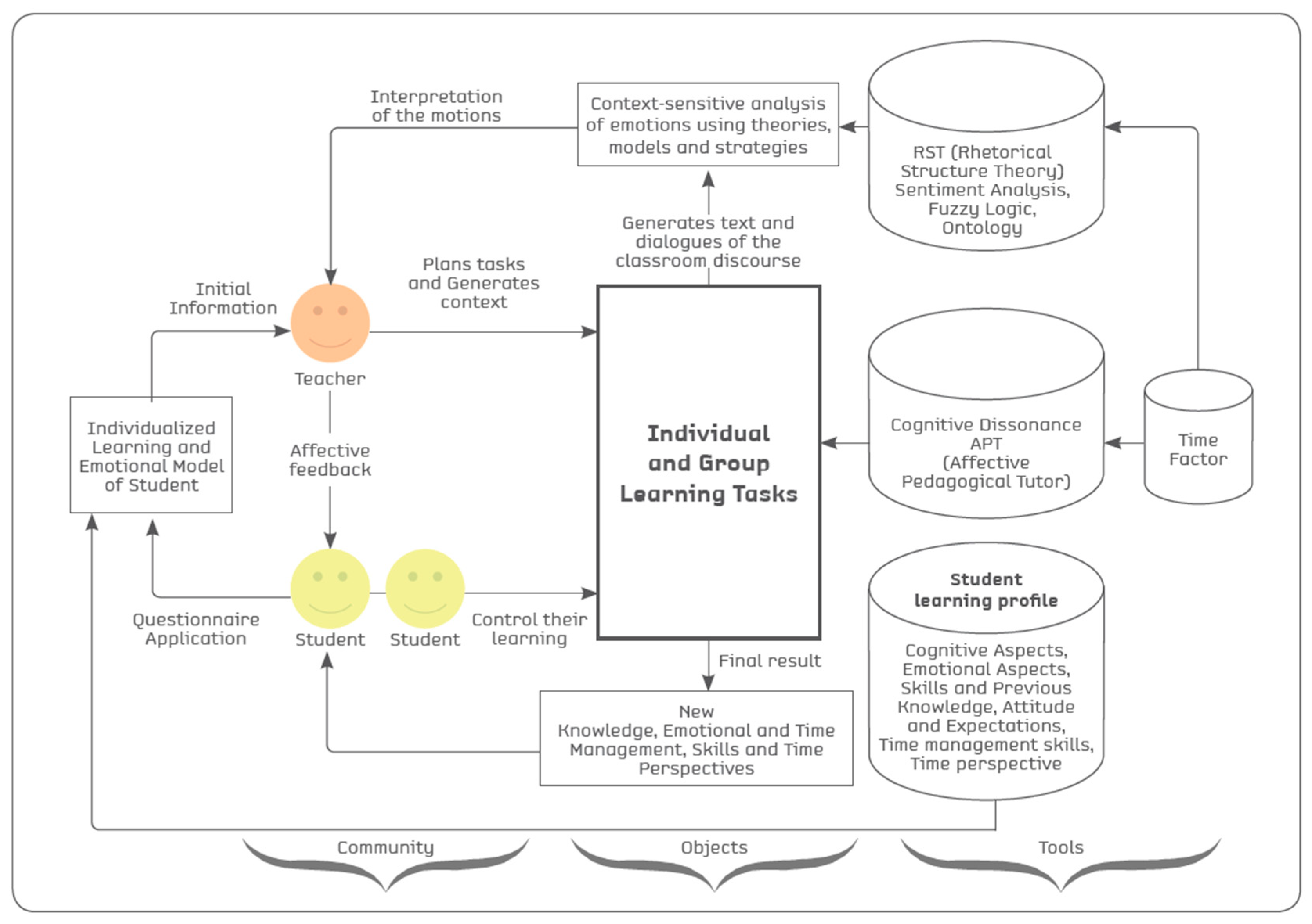

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Aims

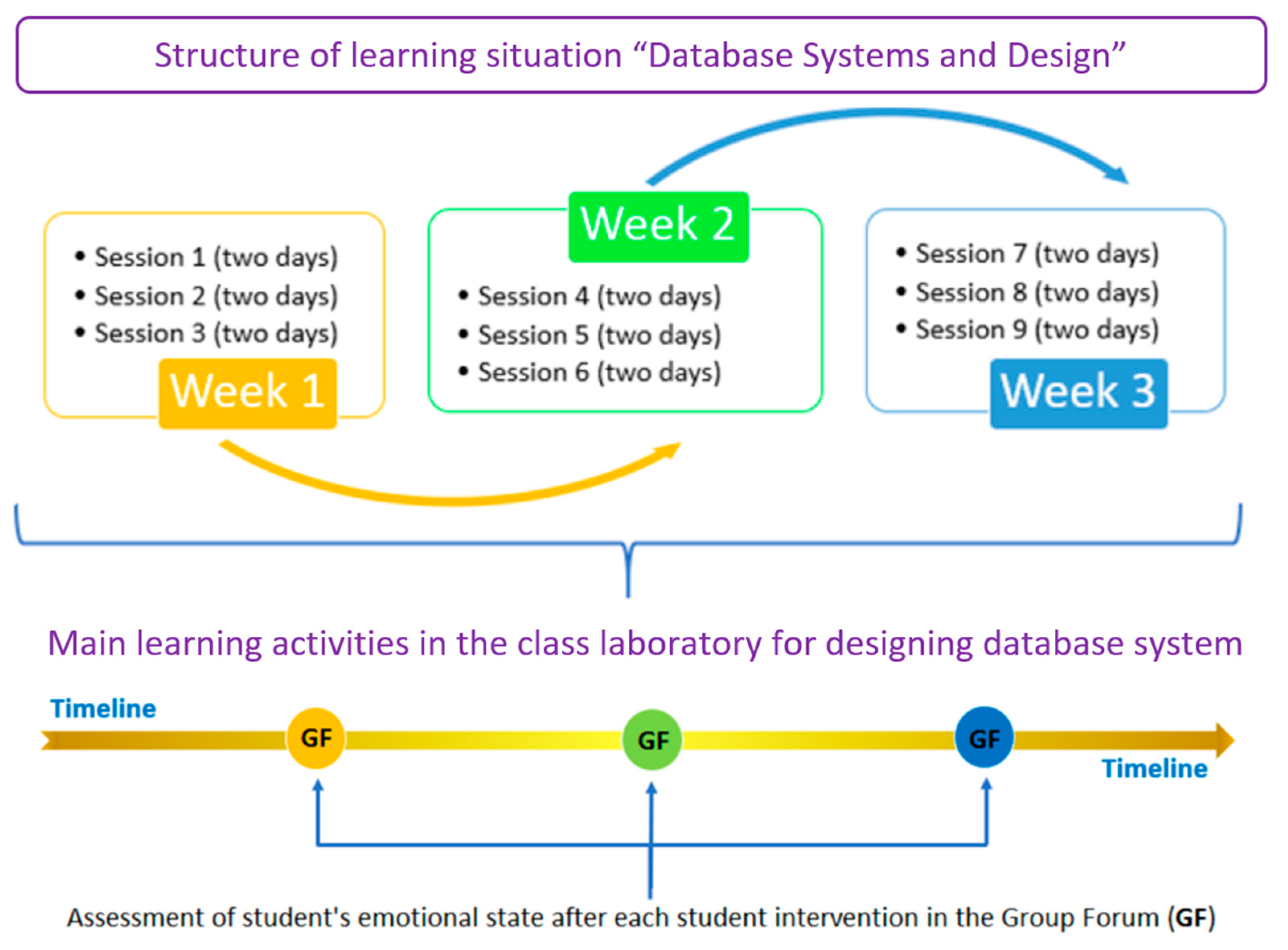

2.1.1. Learning Scenario and Course Context

2.1.2. Research Questions

2.1.3. Definition of Variables for the Learning Situation

2.2. Method

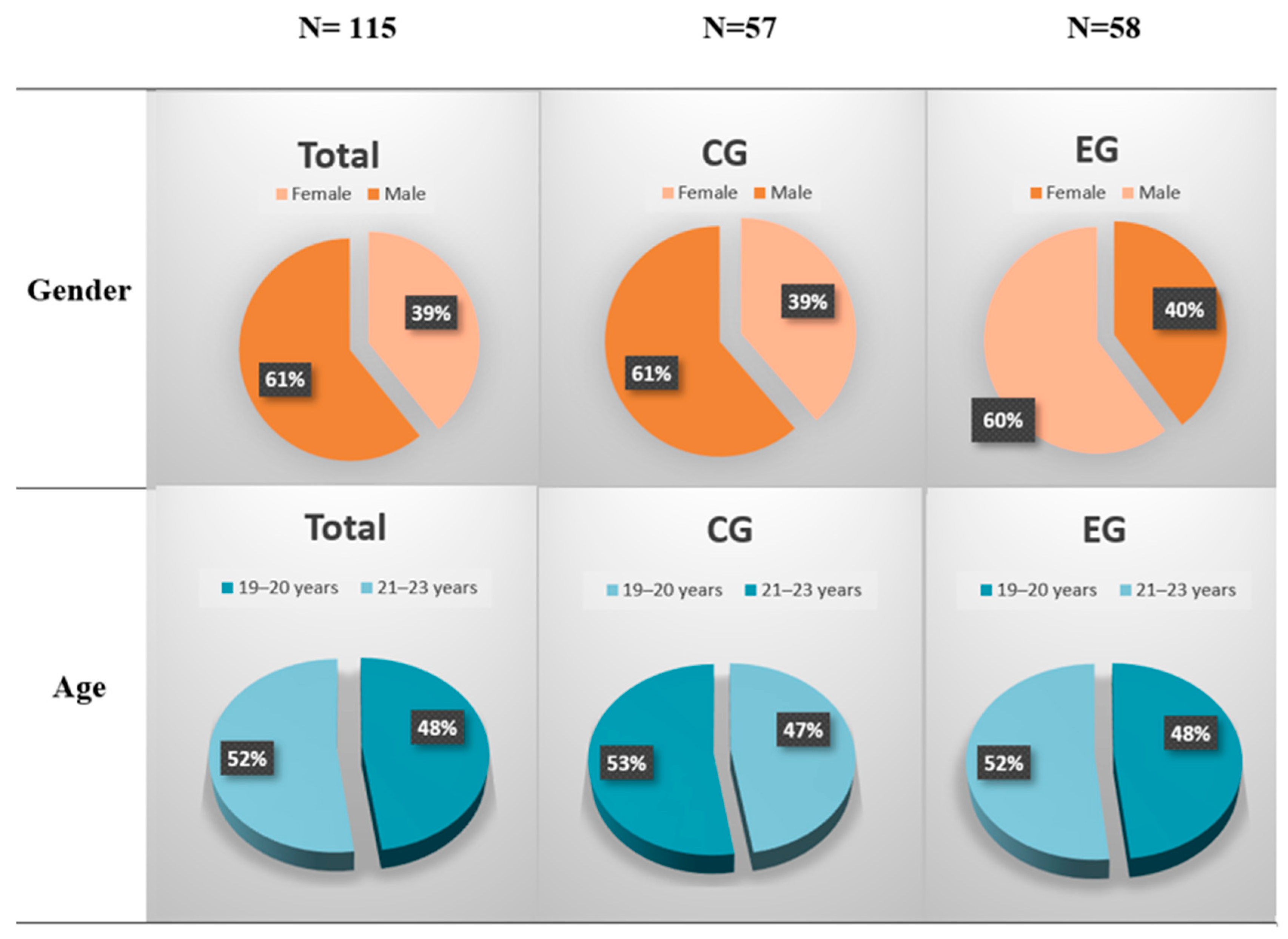

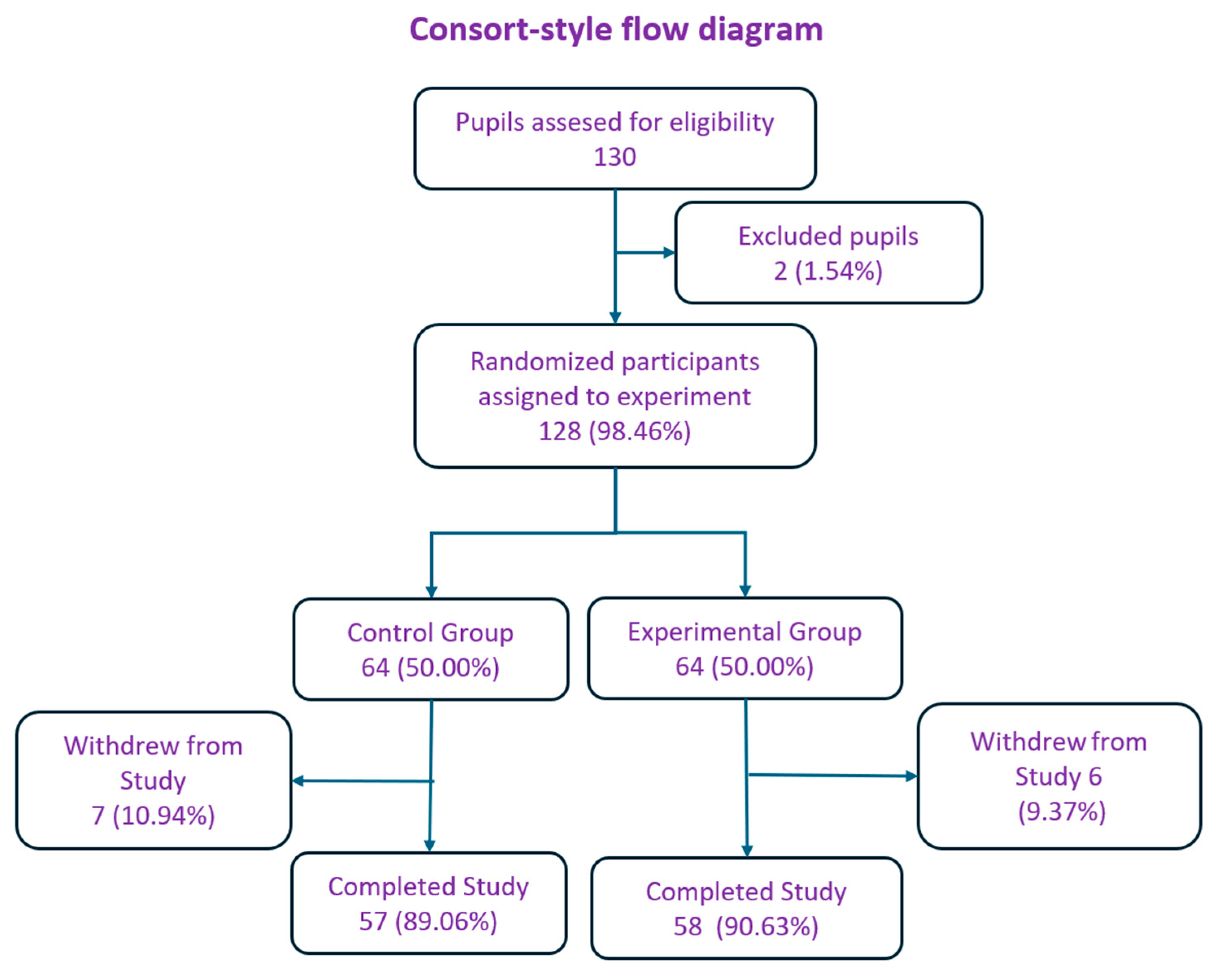

2.2.1. Participant Profile and Research Procedure

| Main Teaching Session Involving Student-Centered Learning Activities | |

|---|---|

| Independent Variables | A = Affective Feedback; C = Cognitive Feedback |

| Dependent Variables | E = Students’ emotional states (we focus on those emotional states that maintain students’ interest toward the activities and learning, as shown in Table 4b) |

| Category | Initial Sample (n = 128) | Final Sample (n = 115) | CG (n = 57) | EE (n = 58) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19–20 years | 61 (47.7%) | 55 (47.8%) | 27 (47.4%) | 28 (48.3%) |

| 21–23 years | 67 (52.3%) | 60 (52.2%) | 30 (52.6%) | 30 (51.7%) | |

| Mean age (SD) | — | 20.4 (±1.1) | 20.4 (±1.1) | 20.4 (±1.1) | 20.5 (±1.1) |

| Gender | Female | 50 (39.0%) | 45 (39.1%) | 22 (38.6%) | 23 (39.7%) |

| Male | 78 (61.0%) | 70 (60.9%) | 35 (61.4%) | 35 (60.3%) | |

| Academic year | 2nd-year undergraduate | 128 (100%) | 115 (100%) | 57 (100%) | 58 (100%) |

| The Cognitive and Affective Feedback Types Provided in the Teaching Sessions 1–9 (a) | |

| Cognitive Feedback | Affective Feedback |

| Make the course objectives clearer and more understandable (3.1) | Create a satisfactory working climate in the group (3.9) |

| Provide students with appropriate and complementary information to increase their ability to complete their work (3.2) | Be subtle enough not to interfere and affect the duration of the course negatively (3.11) |

| Organize and present the contents in a more orderly manner (3.3) | Guide students to better communicate their individual results in the group (3.12) |

| Build on students’ existing knowledge based on their level and needs (3.4) | Help students complete the activity successfully (3.13) |

| Enrich the knowledge presented with novel elements (3.5) | Support students to deal with the final evaluation successfully (3.15) |

| Enable students to work more effectively in small groups (3.6) | Help students acquire skills and attitudes (3.16) |

| Foster individualized learning within working groups (3.7) | Enable students to better face their difficulties (3.17) |

| Provide more support to practical aspects (3.8) | Offer students possibilities to make the best decision in cases of doubt (3.18) |

| Support students’ learning with effective instructional procedures (3.10) | Trigger and maintain students’ interest in the activity and their learning (3.19) |

| Ensure the accomplishment of the learning objectives according to the criteria set by the course (3.14) | — |

| Students’ Emotional States (b) | |

| Code | Emotional State |

| E.1 | Motivated |

| E.2 | Curious |

| E.3 | Confident |

| E.4 | Pleased |

| E.5 | Optimistic/Challenging (Stimulated) |

| E.6 | Insecure or Embarrassed |

| E.7 | Bored |

| E.8 | Anxiety or dismayed |

| E.9 | Outraged |

2.2.2. Instrument Design and Data Collection Procedure

2.2.3. Statistical Assumptions and Research Analyses

3. Results

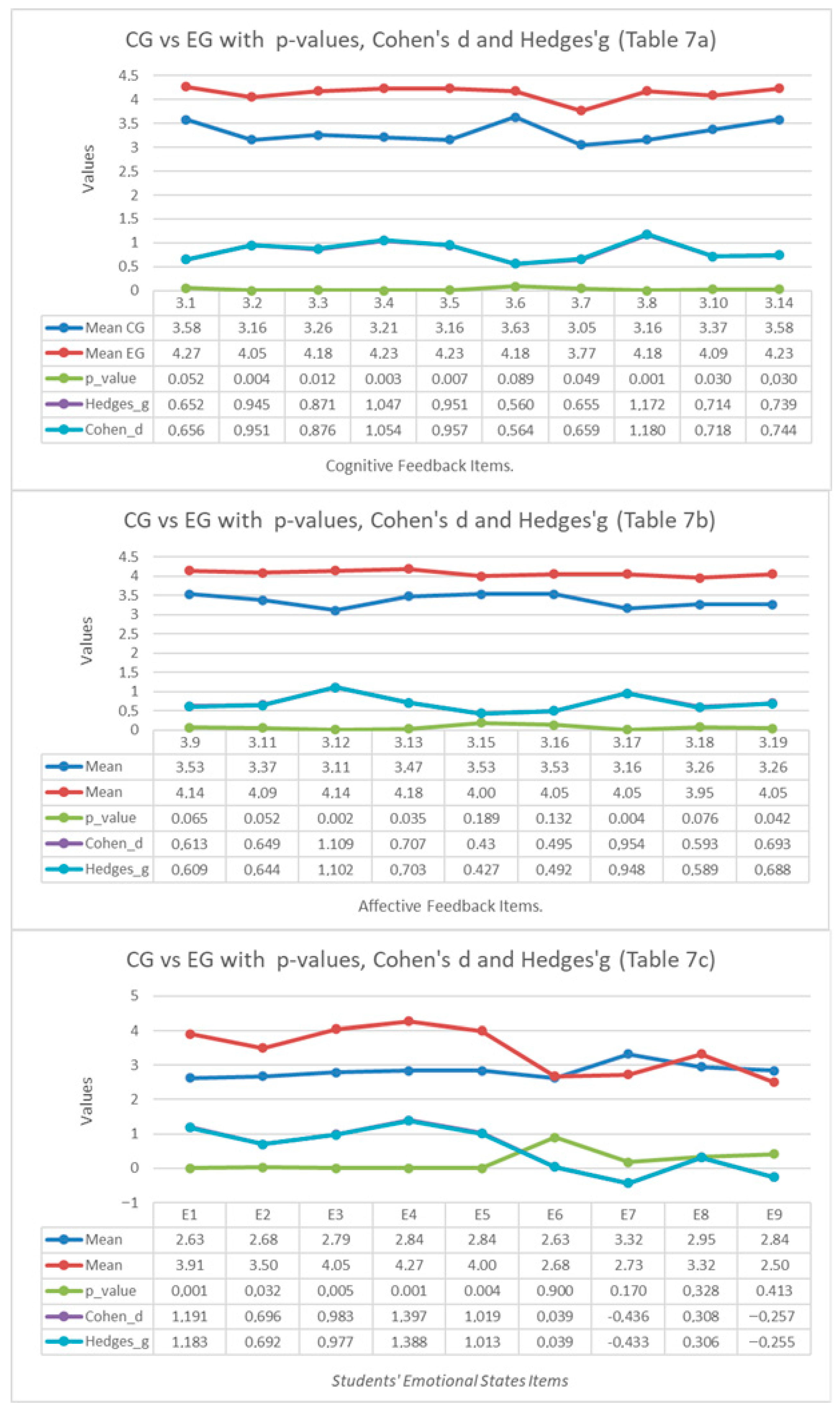

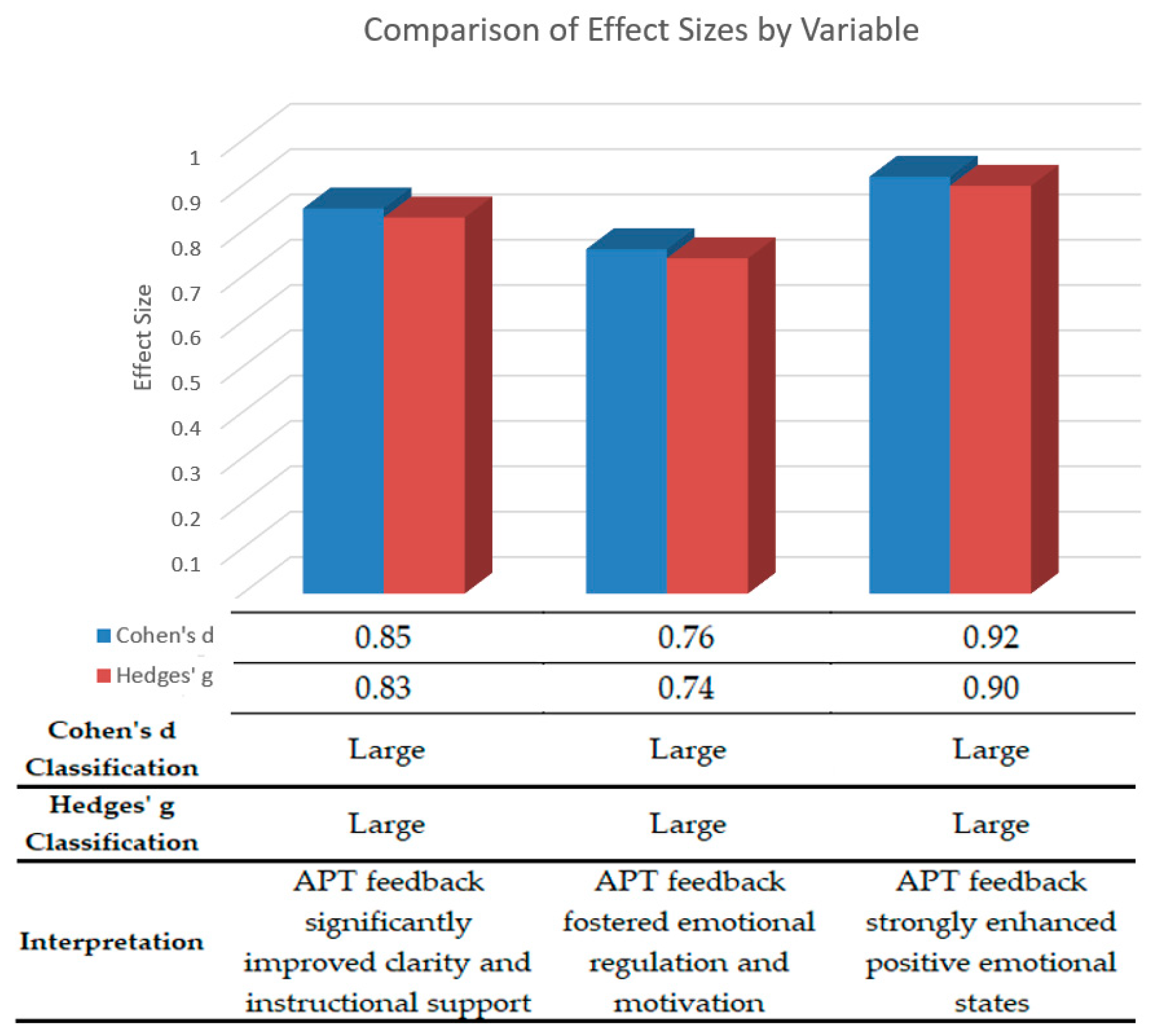

3.1. The Results Regarding RQ1: Have Both the Affective and Cognitive APT Feedback Supported Significantly Student’s Emotional Engagement Compared to Human Teacher’s Feedback?

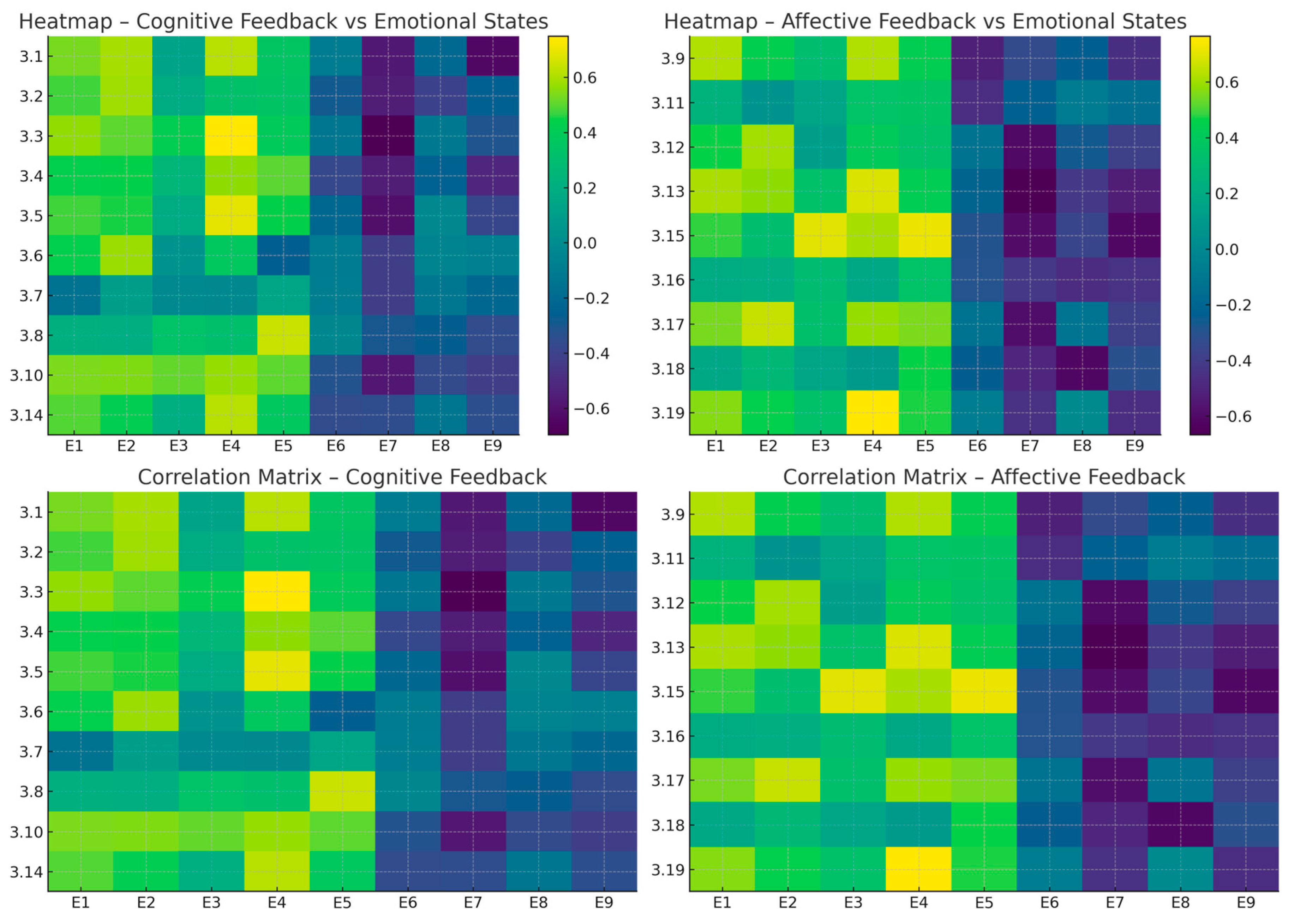

3.2. The Results Regarding RQ2: Is There a Significant Relationship Between All APT Cognitive and Affective Feedback Types and Students’ Emotional States?

3.2.1. Bivariate Analysis

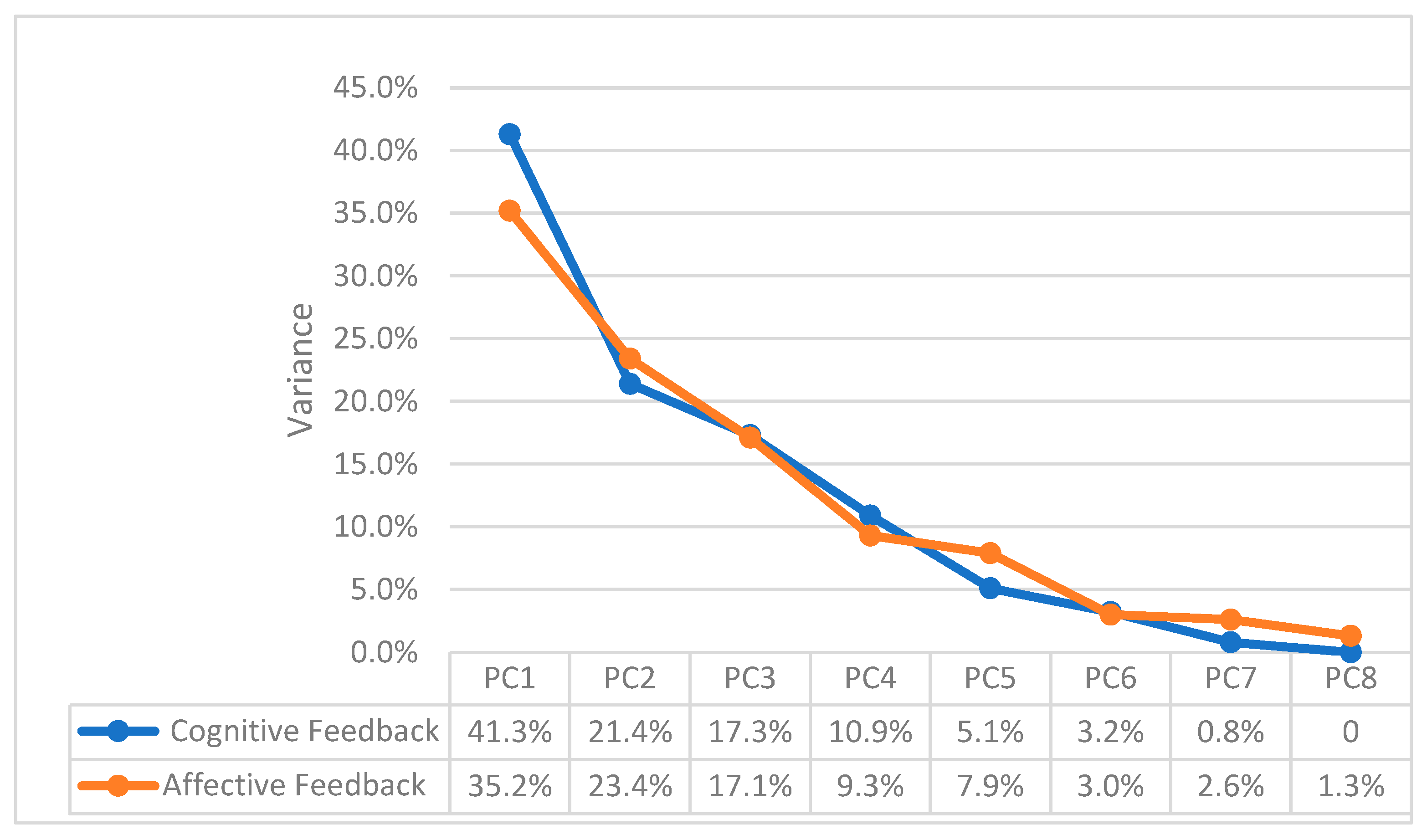

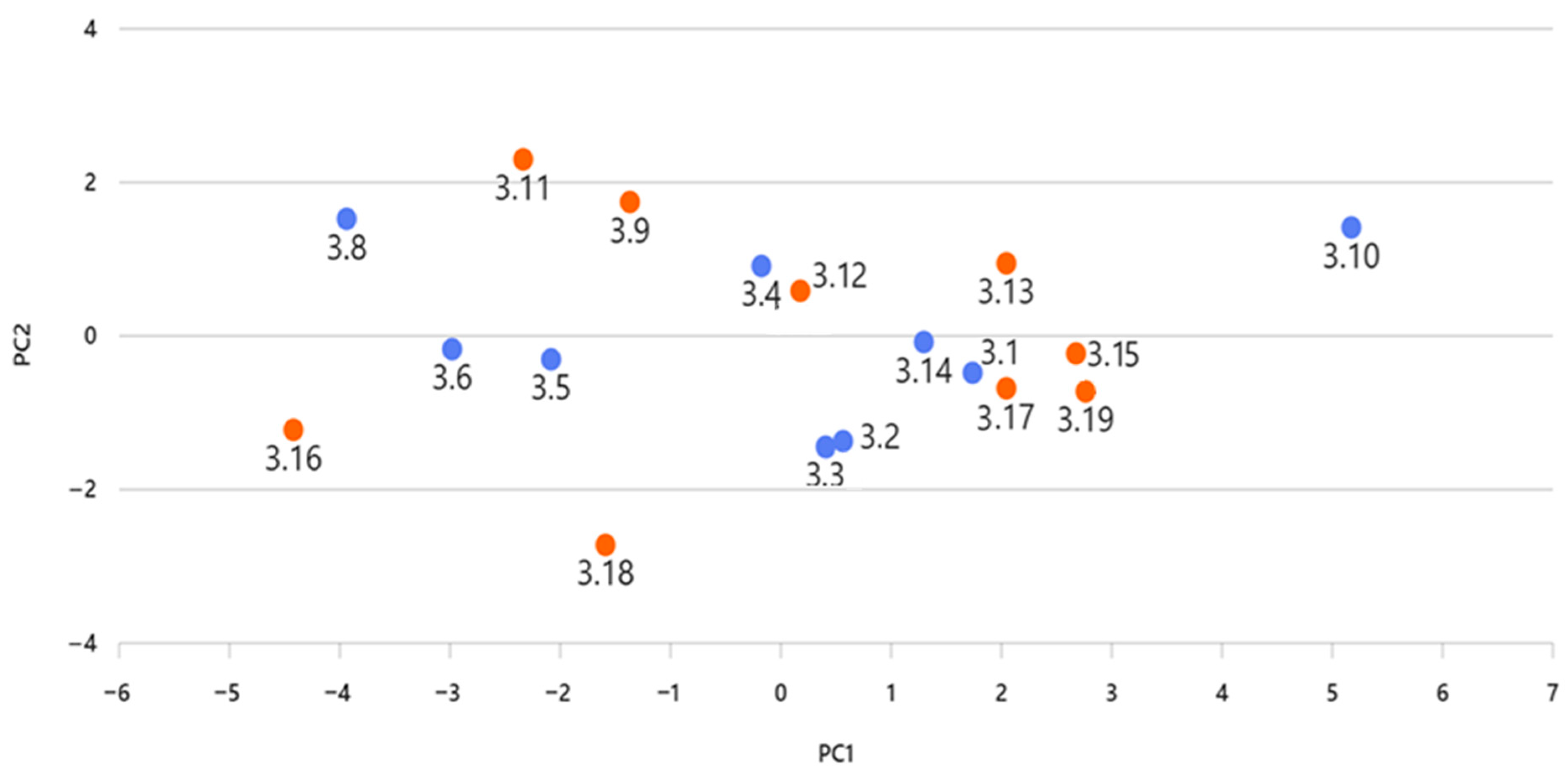

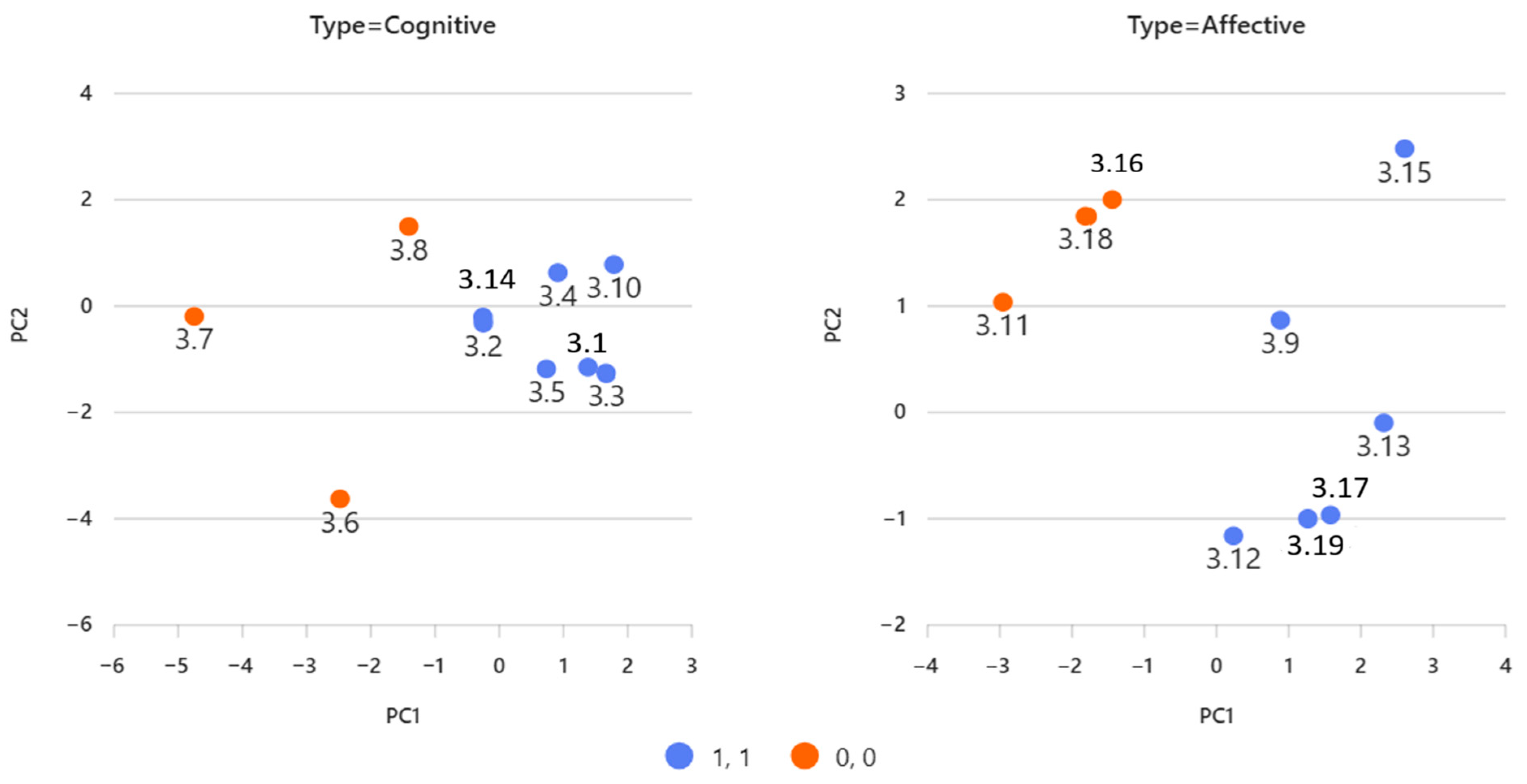

3.2.2. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of RQ1 Findings

4.2. Discussion of RQ2 Findings

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| E.1 | Motivated |

| E.2 | Curious |

| E.3 | Confident |

| E.4 | Pleased |

| E.5 | Optimistic/Challenging (Stimulated) |

| E.6 | Insecure or Embarrassed |

| E.7 | Bored |

| E.8 | Anxiety or dismayed |

| E.9 | Outraged |

| PAD | Pleasure-Arousal-Dominance |

| E | Students’ Emotional States |

| C | Cognitive Feedback |

| A | Affective Feedback |

| CG | Control Group |

| EG | Experimental Group |

| APT | Affective Pedagogical Tutor |

| CPA | Conversational Pedagogical Agents |

Appendix A

- make the course objectives clearer and more understandable to you?

- provide you appropriate and complementary information to increase your ability to complete your work?

- organize and present the contents in a more orderly manner?

- build on your existing knowledge based on your level and needs?

- enrich the knowledge presented with novel elements?

- make you work more effectively in your group?

- foster individualized learning while working in your group?

- provide you more support to practical aspects?

- support your learning with effective instructional procedures?

- ensure the accomplishment of the learning objectives according to the criteria set by the course?

- create a satisfactory working climate in your group?

- be subtle enough not to interfere and affect the duration of the course negatively?

- guide you to better communicate your individual results in your group?

- help you complete the activity successfully?

- support you to deal with the final evaluation successfully?

- help you acquire skills and attitudes?

- make you face your difficulties better?

- offer you possibilities to make the best decision in case of doubt?

- trigger and maintain your interest in the activity and learning?

- motivated you to carry out the activity.

- inspired your curiosity in the activity and the course.

- build your confidence in attaining the activity better.

- brought you joy or satisfaction to keep on with the activity.

- helped you feel more optimistic, challenged or stimulated in your efforts to complete the activity.

- helped you overcome insecurity or embarrassment while doing the activity.

- assisted you to cope with feelings of boredom when they arose during the activity.

- relieved anxiety or feelings of stuck and dismay during the activity.

- helped you deal with your anger or with issues that made you feel outraged.

Appendix B. Box–Cox Transformation Procedure

- represents the original variable (requiring strictly positive values),

- is the transformed variable, and

- is an exponent parameter estimated via maximum likelihood.

- Verification of positive values:All variables were checked to ensure that the raw values were strictly positive, satisfying the requirements of the Box–Cox transformation.

- Estimation of λ:An optimal was computed for each item using maximum likelihood optimization.

- Application of the transformation:Each variable was transformed using its corresponding estimated .

- Post-transformation diagnostics:

- ○

- The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to the transformed variables.

- ○

- Skewness and kurtosis values were computed to assess distributional symmetry and tail behavior.

- ○

- The transformed items demonstrated improved conformity to normality, with non-significant K–S results for nearly all variables (see Table 3).

Appendix C. Complete Statistical Tables for RQ1

| Mean Values of Students’ Learning Outcomes and t-Test Related to Cognitive Feedback (a) | |||||||||||

| Control Group (n = 57) | Experimental Group (n = 58) | Levene’s Test (1) | t-Test for Equality of Means (2) | ||||||||

| Item | Mean (SD) | Min–Max | Mean (SD) | Min–Max | F | p-Value | t | df | p-Value | Cohen’s d | Hedges’ g |

| 3.1 | 3.58 (1.387) | 1–5 | 4.27 (0.550) | 3–5 | 11.416 | <0.001 (b) | −1.975 | 72.934 | 0.052 | 0.656 | 0.652 |

| 3.2 | 3.16 (1.068) | 1–5 | 4.05 (0.785) | 2–5 | 2.243 | 0.137 (a) | −2.938 | 113 | 0.004 | 0.951 | 0.945 |

| 3.3 | 3.26 (1.368) | 1–5 | 4.18 (0.588) | 3–5 | 11.416 | 0.001 (b) | −2.574 | 75.729 | 0.012 | 0.876 | 0.871 |

| 3.4 | 3.21 (1.228) | 1–5 | 4.23 (0.612) | 3–5 | 7.844 | 0.006 (b) | −3.059 | 81.882 | 0.003 | 1.054 | 1.047 |

| 3.5 | 3.16 (1.463) | 1–5 | 4.23 (0.612) | 3–5 | 11.416 | <0.001 (b) | −2.773 | 74.745 | 0.007 | 0.957 | 0.951 |

| 3.6 | 3.63 (1.212) | 1–5 | 4.18 (0.664) | 3–5 | 9.202 | 0.003 (b) | −1.720 | 86.514 | 0.089 | 0.564 | 0.560 |

| 3.7 | 3.05 (1.353) | 1–5 | 3.77 (0.752) | 2–5 | 7.546 | 0.007 (b) | −1.996 | 87.262 | 0.049 | 0.659 | 0.655 |

| 3.8 | 3.16 (1.119) | 1–4 | 4.18 (0.501) | 3–5 | 10.010 | 0.002 (b) | −3.421 | 77.290 | 0.001 | 1.180 | 1.172 |

| 3.10 | 3.37 (1.165) | 1–5 | 4.09 (0.811) | 2–5 | 3.925 | 0.050 (b) | −2.202 | 99.802 | 0.030 | 0.718 | 0.714 |

| 3.14 | 3.58 (1.121) | 1–5 | 4.23 (0.528) | 3–5 | 10.010 | 0.002 (b) | −2.210 | 79.374 | 0.030 | 0.744 | 0.739 |

| Mean Values of Students’ Learning Outcomes and t-Test Related to Affective Feedback (b) | |||||||||||

| Control Group (n = 57) | Experimental Group (n = 58) | Levene’s Test (1) | t-Test for Equality of Means (2) | ||||||||

| Item | Mean (SD) | Min–Max | Mean (SD) | Min–Max | F | p-Value | t | df | p-Value | Cohen’s d | Hedges’ g |

| 3.9 | 3.53 (1.219) | 1–5 | 4.14 (0.710) | 2–5 | 6.369 | 0.013(b) | −1.868 | 89.762 | 0.065 | 0.613 | 0.609 |

| 3.11 | 3.37 (1.383) | 1–5 | 4.09 (0.750) | 2–5 | 10.010 | 0.002 (b) | −1.970 | 85.991 | 0.052 | 0.649 | 0.644 |

| 3.12 | 3.11 (1.150) | 1–5 | 4.14 (0.640) | 2–5 | 5.479 | 0.021 (b) | −3.186 | 87.330 | 0.002 | 1.109 | 1.102 |

| 3.13 | 3.47 (1.219) | 1–5 | 4.18 (0.733) | 2–5 | 5.763 | 0.018 (b) | −2.140 | 91.517 | 0.035 | 0.707 | 0.703 |

| 3.15 | 3.53 (1.389) | 1–5 | 4.00 (0.690) | 2–5 | 11.416 | 0.001 (b) | −1.325 | 81.733 | 0.189 | 0.430 | 0.427 |

| 3.16 | 3.53 (1.264) | 1–5 | 4.05 (0.785) | 2–5 | 6.102 | 0.015 (b) | −1.520 | 93.326 | 0.132 | 0.495 | 0.492 |

| 3.17 | 3.16 (1.015) | 1–4 | 4.05 (0.844) | 2–5 | 1.934 | 0.167 (a) | −2.938 | 113 | 0.004 | 0.954 | 0.948 |

| 3.18 | 3.26 (1.485) | 1–5 | 3.95 (0.722) | 2–5 | 11.416 | <0.001 (b) | −1.797 | 80.759 | 0.076 | 0.593 | 0.589 |

| 3.19 | 3.26 (1.447) | 1–5 | 4.05 (0.722) | 3–5 | 11.416 | 0.001 (b) | −2.066 | 81.937 | 0.042 | 0.693 | 0.688 |

| Mean Values of Students’ Emotional States and t-Test Outcomes Related to Students’ Emotional States (E) (c) | |||||||||||

| Control Group (n = 57) | Experimental Group (n = 58) | Levene’s Test (1) | t-Test for Equality of Means (2) | ||||||||

| Item | Mean (SD) | Min–Max | Mean (SD) | Min–Max | F | p-Value | t | df | p-Value | Cohen’s d | Hedges’ g |

| E1 | 2.63 (1.212) | 1–5 | 3.91 (0.921) | 1–5 | 3.395 | 0.068 (a) | −3.379 | 113 | <0.001 | 1.191 | 1.183 |

| E2 | 2.68 (1.250) | 1–5 | 3.50 (1.102) | 1–5 | 1.066 | 0.304 (a) | −2.171 | 113 | 0.032 | 0.696 | 0.692 |

| E3 | 2.79 (1.548) | 1–5 | 4.05 (0.950) | 2–5 | 6.865 | 0.010 (b) | −2.876 | 92.655 | 0.005 | 0.983 | 0.977 |

| E4 | 2.84 (1.344) | 1–5 | 4.27 (0.550) | 3–5 | 11.416 | <0.001 (b) | −3.427 | 73.981 | <0.001 | 1.397 | 1.388 |

| E5 | 2.84 (1.425) | 1–5 | 4.00 (0.756) | 2–5 | 11.416 | <0.001 (b) | −2.959 | 84.884 | 0.004 | 1.019 | 1.013 |

| E6 | 2.63 (1.257) | 1–5 | 2.68 (1.287) | 1–4 | 0.374 | 0.542 (a) | −0.126 | 113 | 0.900 | 0.039 | 0.039 |

| E7 | 3.32 (1.493) | 1–5 | 2.73 (1.202) | 1–4 | 1.366 | 0.245 (a) | 1.381 | 113 | 0.170 | −0.436 | −0.433 |

| E8 | 2.95 (1.268) | 1–5 | 3.32 (1.129) | 1–5 | 0.177 | 0.675 (a) | −0.982 | 113 | 0.328 | 0.308 | 0.306 |

| E9 | 2.84 (1.344) | 1–5 | 2.50 (1.300) | 1–4 | 0.081 | 0.777 (a) | 0.822 | 113 | 0.413 | −0.257 | −0.255 |

References

- Arguedas, M.; Daradoumis, T.; Xhafa, F. Analyzing how emotion awareness influences students’ motivation, engagement, self-regulation, and learning outcome. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2016, 19, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T.; Titz, W.; Perry, R.P. Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 37, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kort, B.; Reilly, R. Analytical models of emotions, learning, and relationships: Towards an affect-sensitive cognitive machine. In Proceedings of the Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems, Biarritz, France and San Sebastian, Spain, 2–7 June 2002; pp. 955–962. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R. Progress and open problems in educational emotion research. Learn. Instr. 2005, 15, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, S.K.; Taylor, R.S.; Graesser, A.C. Monitoring affective trajectories during complex learning. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Nashville, TN, USA, 1–4 August 2007; pp. 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Johnson, S.D. Relationship between students’ emotional intelligence, social bond, and interactions in online learning. Internet High. Educ. 2012, 15, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Devis-Rozental, C.; Eccles, S.; Mayer, P. Developing socio-emotional intelligence in higher education learners. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2017, 41, 146–162. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R.K. Optimizing learning from examples using animated pedagogical agents. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 94, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daradoumis, T.; Arguedas, M. Cultivating students’ reflective learning in metacognitive activities through an affective pedagogical agent. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2020, 23, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ammar, M.B.; Neji, M.; Alimi, A.M.; Gouarderes, G. Emotional multi-agent system for e-learning. Int. J. Knowl. Soc. Res. 2010, 1, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Scholten, M.R.M.; Kelders, S.M.; Van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E.W.C. Self-guiding eHealth to support standardized health care and knowledge dissemination: A concept design. Health Policy Technol. 2017, 6, 356–364. [Google Scholar]

- Heidig, S.; Clarebout, G. Do pedagogical agents make a difference to students’ motivation and learning? Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, N.L.; Adesope, O.O.; Gilbert, R.B. A meta-analytic review of the modality and contiguity effects in multimedia learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 25, 569–590. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, N.L.; Romine, W.L.; Craig, S.D. Cognitive load, split attention, and the impact of technology on mathematics achievement. Comput. Educ. 2017, 105, 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dinçer, S.; Doğanay, A. The effects of multiple-pedagogical-agent learning environments on academic achievement, motivation, and cognitive load. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 74, 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Martha, S.G.; Santoso, H.B. The effectiveness of pedagogical agents in learning: A systematic review. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2019, 14, 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J.; Timperley, H. The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, E.R. Providing feedback on computer-based algebra homework in middle school classrooms. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 108, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narciss, S. Designing and evaluating informative tutoring feedback for digital learning environments. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2013, 22, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Timmers, C.F.; Walraven, A.; Veldkamp, B.P. The effect of feedback on metacognition, self-regulation, and performance: A systematic review of studies in secondary and higher education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 14, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, B.; Thomas, R.C.; Rawson, K.A. Learning more from feedback: Elaborating feedback with examples enhances concept learning. Learn. Instr. 2018, 54, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachner, A.; Burkhart, C.; Nückles, M. Mind the gap! Automated concept mapping supports memory and transfer of knowledge from expository science texts. Learn. Instr. 2017, 49, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe, E.R.; Rittle-Johnson, B. Feedback both helps and hinders learning: The causal role of prior knowledge. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 108, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kleij, F.M.; Feskens, R.C.W.; Eggen, T.J.H.M. Effects of feedback in computer-based learning environments: A meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2015, 85, 475–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Atkinson, R.K.; Christopherson, M.; Joseph, S.S.; Harrison, C. Verbal feedback by animated pedagogical agents and its impact on learners. Comput. Educ. 2013, 62, 263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Attali, Y.; Laitusis, C.; Stone, E. Feedback content and learning outcomes. Educ. Assess. 2016, 21, 344–363. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Gong, J.; Xu, J.; Hu, X. The role of elaborated feedback in learning: A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 763–781. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.; Li, Z. Implementing emotion-based user-aware e-learning. In Proceedings of the CHI’09 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 4–9 April 2009; pp. 3787–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, J.L.; McQuiggan, S.W.; Lester, J.C. Modeling task-based vs. affect-based feedback behavior in pedagogical agents: A quantitative analysis. In Proceedings of the 2009 Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education: Building Learning Systems that Care: From Knowledge Representation to Affective Modelling, Brighton, UK, 6–10 July 2009; pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- D’Mello, S.K.; Lehman, B.; Graesser, A.C. A motivationally supportive affect-sensitive intelligent tutoring system. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2011, 21, 77–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.R.; Goh, D.H.L. Evaluation of affective embodied agents in an information literacy game. Comput. Educ. 2016, 103, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, T.W.; Mat Zin, N.A.; Sahari, N. Exploring the affective, motivational and cognitive effects of pedagogical agent enthusiasm in a multimedia learning environment. Hum.-Centric Comput. Inf. Sci. 2017, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Ginns, P.; Wang, T.; Zhang, P. Pedagogical agents in educational contexts: A meta-analysis of their effects on learning and affective outcomes. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2020, 36, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, M.; Mustafa, M.B.; Lahsasna, A. A review of emotion regulation in intelligent tutoring systems. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2015, 18, 435–445. [Google Scholar]

- Cabestrero, R.; Crespo, A.; Pérez-Sánchez, M.; Fernández-Escribano, M.; Ledesma, J.C. Effects of encouraging feedback on student engagement: A field study. Learn. Instr. 2018, 56, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrie, C.R.; Halverson, L.R.; Graham, C.R. Measuring student engagement in technology-mediated learning: A review. Comput. Educ. 2015, 90, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.; Mavrikis, M.; Hansen, A.; Grawemeyer, B. Purpose and Level of Feedback in an Exploratory Learning Environment for Fractions. In Artificial Intelligence in Education; AIED 2015; Conati, C., Heffernan, N., Mitrovic, A., Verdejo, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grawemeyer, B.; Mavrikis, M.; Holmes, W.; Gutiérrez-Santos, S.; Wiedmann, M.; Rummel, N. Affective learning: Improving engagement and enhancing learning with affect-aware feedback. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2017, 27, 119–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, R.; Iyer, S.; Murthy, S. Personalized affective feedback to address students’ frustration in ITS. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2018, 12, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayordomo, R.M.; Espasa, A.; Guasch, T.; Martínez-Melo, M. Perception of online feedback and its impact on cognitive and emotional engagement with feedback. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 7947–7971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.L.; Wang, T.H.; Lin, H.C.K.; Lai, C.F.; Huang, Y.M. The influence of affective feedback adaptive learning system on learning engagement and self-directed learning. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 858411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Herrero, J. Evaluating recent advances in affective intelligent tutoring systems: A scoping review of educational impacts and future prospects. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y.; Miettinen, R.; Punamäki, R.L. Perspectives on Activity Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguedas, M.; Casillas, L.; Xhafa, F.; Daradoumis, T.; Peña, A.; Caballé, S. A fuzzy-based approach for classifying students’ emotional states in online collaborative work. In Proceedings of the 2016 10th International Conference on Complex, Intelligent, and Software Intensive Systems (CISIS), Fukuoka, Japan, 6–8 July 2016; pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguedas, M.; Xhafa, F.; Casillas, L.; Daradoumis, T.; Peña, A.; Caballé, S. A model for providing emotion awareness and feedback using fuzzy logic in online learning. Soft Comput. 2018, 22, 963–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguedas, M.M.; Daradoumis, T. Exploring learners’ emotions over time in virtual learning. eLearn Cent. Res. Pap. Ser. 2013, 6, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; O’Reilly, E. Effects of personality and situational variables on communication accuracy. Psychol. Rep. 1980, 46, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluck, G.; Johnson, H.L. Stimulating curiosity to enhance learning. Educ. Sci. Psychol. 2011, 19, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Icekson, T.; Roskes, M.; Moran, S. Effects of optimism on persistence and motivation in goal pursuit. Motiv. Emot. 2014, 38, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D.; Marshall, M.A. The three faces of self-esteem. In Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Group Processes; Hogg, M., Tindale, R., Eds.; Blackwell: London, UK, 2001; pp. 232–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.C. Hope, problem-solving ability, and coping in a college student population: Some implications for theory and practice. J. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 54, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 10th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gravetter, F.J.; Wallnau, L.B. Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 8th ed.; Wadsworth Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L.V.; Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arguedas, M.; Daradoumis, T.; Caballé, S. Measuring the effects of pedagogical agent cognitive and affective feedback on students’ academic performance. Front. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 1495342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beege, M.; Schneider, B. Emotional design of pedagogical agents: The influence of enthusiasm and model-observer similarity. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2023, 71, 859–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lang, Y.; Gong, S.; Xie, K.; Cao, Y. The impact of emotional and elaborated feedback of a pedagogical agent on multimedia learning. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 810194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, Y.; Gong, S.; Hu, X.; Xiao, B.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, T. The roles of pedagogical agent’s emotional support: Dynamics between emotions and learning strategies in multimedia learning. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2024, 62, 1485–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ochoa, E.; Arguedas, M.; Daradoumis, T. Empathic pedagogical conversational agents: A systematic literature review. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55, 886–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Jiang, L.; Liu, G.; Li, H. The interaction effect of pedagogical agent and emotional feedback on effective learning: A 2 × 2 factorial experiment in online formative assessment. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1610550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ji, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, T.; Xu, W. A Data-Driven Adaptive Emotion Recognition Model for College Students Using an Improved Multifeature Deep Neural Network Technology. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 1343358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khediri, N.; Ben Ammar, M.; Kherallah, M. A real-time multimodal intelligent tutoring emotion recognition system (MITERS). Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 57759–57783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Krieglstein, F.; Beege, M.; Rey, G.D. The impact of video lecturers’ nonverbal communication on learning–An experiment on gestures and facial expressions of pedagogical agents. Comput. Educ. 2022, 176, 104350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabestrero, R.; Quirós, P.; Santos, O.C.; Salmeron-Majadas, S.; Uria-Rivas, R.; Boticario, J.G.; Arnau, D.; Arevalillo-Herráez, M.; Ferri, F.J. Some insights into the impact of affective information when delivering feedback to students. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 37, 1252–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, H.; Money, A.; Daylamani-Zad, D. Pedagogical AI conversational agents in higher education: A conceptual framework and survey of the state of the art. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2025, 73, 815–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E.P.; Cox, D.R. An analysis of transformations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1964, 26, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Sessions/Week | Description of Activities | Instructor Role | APT Role | Data Collected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1—Orientation and initial briefing | Session 1, Week 1 | Overview of objectives, emotional-engagement concepts, tools. Baseline info collected. | Leads introduction, collects baseline info. | Not active. | Prior SQL experience, initial motivation responses. |

| Step 2—Baseline instruction and initial practice | Sessions 2–3, Week 1 | Intro SQL tasks. CG: instructor-only feedback. EG: APT cognitive and affective feedback. | Monitors task completion and provide feedback to CG. | Analyzes text and triggers feedback in EG. | Completion times, help requests, APT outputs, emotional-linguistic indicators. |

| Step 3—Collaborative project development | Sessions 4–6, Week 2 | Team SQL project. Emotional states monitored every 15 min. | Facilitates teamwork, evaluates SQL. | Detects frustration/engagement and issues feedback. | Forum messages, SQL errors, emotional timestamps, APT interventions. |

| Step 4—Consolidation and reflection | Sessions 7–8, Week 3 | Advanced SQL tasks and reflection. Threshold-based feedback. | Supports reflection and monitor’s progress. | Triggers feedback at emotional thresholds. | Reflective notes, emotional updates, performance indicators, intervention logs. |

| Step 5—Post-test evaluation | Session 9, Week 3 | Final surveys on emotional engagement and feedback perception. | Supervises assessment. | Not active. | Survey responses, interaction logs, emotional-state data export. |

| Cognitive Feedback | Affective Feedback | Students’ Emotional States | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | EG | CG | EG | CG | EG | |||

| Variable | p-Value | p-Value | Variable | p-Value | p-Value | Variable | p-Value | p-Value |

| 3.1 | 0.3756 | 0.5340 | 3.9 | 0.6934 | 0.246 | E.1 | 0.2290 | 0.7122 |

| 3.2 | 0.3223 | 0.6344 | 3.11 | 0.0230 | 0.2383 | E.2 | 0.7780 | 0.7999 |

| 3.3 | 0.8239 | 0.2007 | 3.12 | 0.9414 | 0.5375 | E.3 | 0.4293 | 0.5486 |

| 3.4 | 0.6922 | 0.4315 | 3.13 | 0.4675 | 0.8211 | E.4 | 0.8857 | 0.0231 |

| 3.5 | 0.2276 | 0.5522 | 3.15 | 0.3847 | 0.1454 | E.5 | 0.8885 | 0.2224 |

| 3.6 | 0.1819 | 0.8702 | 3.16 | 0.2438 | 0.7254 | E.6 | 0.7305 | 0.5581 |

| 3.7 | 0.4488 | 0.8588 | 3.17 | 0.3951 | 0.3981 | E.7 | 0.8104 | 0.5046 |

| 3.8 | 0.2931 | 0.6593 | 3.18 | 0.1332 | 0.2723 | E.8 | 0.7190 | 0.2898 |

| 3.10 | 0.5911 | 0.5809 | 3.19 | 0.5580 | 0.8034 | E.9 | 0.8481 | 0.5915 |

| 3.14 | 0.1652 | 0.2593 | ||||||

| Cognitive Feedback | Variable | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.10 | 3.14 | |

| CG | Skewness | −0.19 | −0.31 | −0.36 | −0.46 | −0.09 | 0.19 | −0.53 | −0.27 | −0.11 | −0.12 | |

| Kurtosis | −0.92 | −0.99 | −1.14 | −0.86 | −0.91 | −1.06 | −1.03 | −1.09 | −1.01 | −0.92 | ||

| EG | Skewness | −0.28 | −0.14 | −0.4 | −0.35 | −0.08 | 0.22 | −0.39 | −0.33 | −0.1 | −0.24 | |

| Kurtosis | −0.84 | −1.02 | −0.89 | −0.78 | −0.96 | −0.97 | −1.06 | −1.01 | −1.05 | −0.96 | ||

| Affective Feedback | Variable | 3.9 | 3.11 | 3.12 | 3.13 | 3.15 | 3.16 | 3.17 | 3.18 | 3.19 | ||

| CG | Skewness | −0.19 | 0.39 | −0.45 | −0.24 | −0.21 | −0.11 | 0.05 | 0.1 | −0.11 | ||

| Kurtosis | −0.99 | −0.63 | −0.87 | −0.89 | −1.03 | −0.95 | −1.12 | −0.96 | −0.87 | |||

| EG | Skewness | −0.25 | 0.11 | −0.31 | −0.19 | −0.35 | −0.27 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.13 | ||

| Kurtosis | −0.99 | −0.84 | −0.91 | −0.93 | −1.08 | −0.93 | −1.04 | −0.87 | −0.89 | |||

| Students’ emotional states | Variable | E.1 | E.2 | E.3 | E.4 | E.5 | E.6 | E.7 | E.8 | E.9 | ||

| CG | Skewness | −0.33 | −0.41 | −0.27 | −0.06 | −0.12 | −0.19 | −0.17 | −0.28 | −0.29 | ||

| Kurtosis | −0.81 | −0.92 | −0.87 | −0.73 | −0.91 | −0.99 | −0.94 | −0.97 | −0.95 | |||

| EG | Skewness | −0.35 | −0.43 | −0.29 | 0.14 | −0.18 | −0.21 | −0.24 | −0.27 | −0.22 | ||

| Kurtosis | −0.85 | −0.91 | −0.88 | −0.54 | −0.83 | −0.91 | −0.98 | −0.95 | −0.91 |

| Mean Values of Students’ Learning Outcomes and t-Test Related to Cognitive Feedback (a) | |||||||

| Control Group (n = 57) | Experimental Group (n = 58) | t-Test for Equality of Means | |||||

| Item | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p_Value | Cohen_d | Hedges_g |

| 3.1 | 3.58 | 1.387 | 4.27 | 0.550 | 0.052 | 0.656 | 0.652 |

| 3.2 | 3.16 | 1.068 | 4.05 | 0.785 | 0.004 | 0.951 | 0.945 |

| 3.3 | 3.26 | 1.368 | 4.18 | 0.588 | 0.012 | 0.876 | 0.871 |

| 3.4 | 3.21 | 1.228 | 4.23 | 0.612 | 0.003 | 1.054 | 1.047 |

| 3.5 | 3.16 | 1.463 | 4.23 | 0.612 | 0.007 | 0.957 | 0.951 |

| 3.6 | 3.63 | 1.212 | 4.18 | 0.664 | 0.089 | 0.564 | 0.560 |

| 3.7 | 3.05 | 1.353 | 3.77 | 0.752 | 0.049 | 0.659 | 0.655 |

| 3.8 | 3.16 | 1.119 | 4.18 | 0.501 | 0.001 | 1.180 | 1.172 |

| 3.10 | 3.37 | 1.165 | 4.09 | 0.811 | 0.030 | 0.718 | 0.714 |

| 3.14 | 3.58 | 1.121 | 4.23 | 0.528 | 0.030 | 0.744 | 0.739 |

| MEAN values of Students’ Learning Outcomes and t-Test Related to Affective Feedback (b) | |||||||

| Control Group (n = 57) | Experimental Group (n = 58) | t-Test for Equality of Means | |||||

| Item | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p_Value | Cohen_d | Hedges_g |

| 3.9 | 3.53 | 1.219 | 4.14 | 0.710 | 0.065 | 0.613 | 0.609 |

| 3.11 | 3.37 | 1.383 | 4.09 | 0.750 | 0.052 | 0.649 | 0.644 |

| 3.12 | 3.11 | 1.15 | 4.14 | 0.640 | 0.002 | 1.109 | 1.102 |

| 3.13 | 3.47 | 1.219 | 4.18 | 0.733 | 0.035 | 0.707 | 0.703 |

| 3.15 | 3.53 | 1.389 | 4.00 | 0.690 | 0.189 | 0.43 | 0.427 |

| 3.16 | 3.53 | 1.264 | 4.05 | 0.785 | 0.132 | 0.495 | 0.492 |

| 3.17 | 3.16 | 1.015 | 4.05 | 0.844 | 0.004 | 0.954 | 0.948 |

| 3.18 | 3.26 | 1.485 | 3.95 | 0.722 | 0.076 | 0.593 | 0.589 |

| 3.19 | 3.26 | 1.447 | 4.05 | 0.722 | 0.042 | 0.693 | 0.688 |

| Mean Values of Students’ Emotional States and t-Test Outcomes Related to Students’ Emotional States (E) (c) | |||||||

| Control Group (n = 57) | Experimental Group (n = 58) | t-Test for Equality of Means | |||||

| Item | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p_Value | Cohen_d | Hedges_g |

| E1 | 2.63 | 1.212 | 3.91 | 0.921 | 0.001 | 1.191 | 1.183 |

| E2 | 2.68 | 1.25 | 3.50 | 1.102 | 0.032 | 0.696 | 0.692 |

| E3 | 2.79 | 1.548 | 4.05 | 0.950 | 0.005 | 0.983 | 0.977 |

| E4 | 2.84 | 1.344 | 4.27 | 0.550 | 0.001 | 1.397 | 1.388 |

| E5 | 2.84 | 1.425 | 4.00 | 0.756 | 0.004 | 1.019 | 1.013 |

| E6 | 2.63 | 1.257 | 2.68 | 1.287 | 0.900 | 0.039 | 0.039 |

| E7 | 3.32 | 1.493 | 2.73 | 1.202 | 0.170 | −0.436 | −0.433 |

| E8 | 2.95 | 1.268 | 3.32 | 1.129 | 0.328 | 0.308 | 0.306 |

| E9 | 2.84 | 1.344 | 2.50 | 1.300 | 0.413 | −0.257 | −0.255 |

| Pearson Correlations Between APT Cognitive Feedback and Students’ Emotional Engagement in Experimental Group (EG, n = 58) (a) | |||||||||

| Total Number of Students of Experimental Group | |||||||||

| E.1 | E.2 | E.3 | E.4 | E.5 | E.6 | E.7 | E.8 | E.9 | |

| 3.1 | 0.531 * | 0.592 ** | 0.137 | 0.618 ** | 0.358 | −0.094 | −0.576 ** | −0.203 | −0.634 ** |

| 3.2 | 0.477 * | 0.581 ** | 0.189 | 0.328 | 0.346 | −0.285 | −0.556 * | −0.404 | −0.253 |

| 3.3 | 0.565 * | 0.506 * | 0.421 | 0.749 ** | 0.393 | −0.134 | −0.696 ** | −0.120 | −0.308 |

| 3.4 | 0.428 | 0.444 | 0.258 | 0.560 * | 0.496 * | −0.379 | −0.553 * | −0.242 | −0.517 * |

| 3.5 | 0.473 * | 0.454 | 0.187 | 0.691 ** | 0.439 | −0.208 | −0.609 ** | −0.025 | −0.382 |

| 3.6 | 0.432 | 0.579 ** | 0.045 | 0.372 | −0.261 | −0.094 | −0.424 | −0.049 | −0.072 |

| 3.7 | −0.157 | 0.109 | −0.021 | −0.026 | 0.149 | −0.086 | −0.421 | −0.128 | −0.209 |

| 3.8 | 0.209 | 0.197 | 0.341 | 0.313 | 0.644 ** | −0.035 | −0.298 | −0.268 | −0.352 |

| 3.10 | 0.535 * | 0.542 * | 0.507 * | 0.571 * | 0.506 * | −0.320 | −0.582 ** | −0.362 | −0.422 |

| 3.14 | 0.493 * | 0.415 | 0.202 | 0.617 ** | 0.373 | −0.353 | −0.348 | −0.134 | −0.341 |

| Pearson Correlations Between APT Affective Feedback and Students’ Emotional Engagement in the Experimental Group (EG, n = 58). (b) | |||||||||

| Total Number of Students of Experimental Group | |||||||||

| E.1 | E.2 | E.3 | E.4 | E.5 | E.6 | E.7 | E.8 | E.9 | |

| 3.9 | 0.628 ** | 0.444 | 0.327 | 0.630 ** | 0.435 | −0.519 * | −0.341 | −0.233 | −0.455 |

| 3.11 | 0.251 | 0.071 | 0.168 | 0.362 | 0.370 | −0.461 * | −0.221 | −0.083 | −0.146 |

| 3.12 | 0.468 * | 0.605 ** | 0.138 | 0.407 | 0.350 | −0.125 | −0.603 ** | −0.263 | −0.384 |

| 3.13 | 0.614 ** | 0.578 ** | 0.350 | 0.692 ** | 0.429 | −0.206 | −0.667 ** | −0.414 | −0.528 * |

| 3.15 | 0.485 * | 0.325 | 0.700 ** | 0.612 ** | 0.718 ** | −0.296 | −0.594 ** | −0.362 | −0.608 ** |

| 3.16 | 0.206 | 0.217 | 0.315 | 0.182 | 0.357 | −0.291 | −0.417 | −0.467 * | −0.439 |

| 3.17 | 0.547 * | 0.655 ** | 0.341 | 0.590 ** | 0.556 * | −0.126 | −0.585 ** | −0.123 | −0.388 |

| 3.18 | 0.180 | 0.287 | 0.170 | 0.105 | 0.467 * | −0.243 | −0.491 * | −0.612 ** | −0.312 |

| 3.19 | 0.565 * | 0.448 | 0.348 | 0.765 ** | 0.479 * | −0.066 | −0.452 | 0.008 | −0.463 * |

| Domain | Empirical Pattern (CG vs. EG) | Statistical Evidence Reported | Substantive Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive feedback items (Table 7a) | EG shows higher mean scores than CG across all cognitive feedback items. | Several items show statistically significant differences in favor of EG, with moderate to large effect sizes (Cohen’s d, Hedges’ g), as reported in Table 7a. | APT cognitive feedback improves clarity, organization and perceived instructional support compared to human-teacher feedback. |

| Affective feedback items (Table 7b) | EG consistently reports higher affective feedback ratings than CG. | Multiple items present significant differences with moderate to large effect sizes, as shown in Table 7b. | APT affective feedback enhances students’ motivation and emotional regulation, supporting higher emotional engagement. |

| Positive emotional states (E1–E5, Table 7c) | EG reports higher levels of motivation, curiosity, confidence, pleasure and stimulation. | Significant differences and large effect sizes for several positive emotions in favor of EG, as indicated in Table 7c. | APT feedback is strongly associated with increases in positive emotional engagement. |

| Negative emotional states (E6–E9, Table 7c) | Differences between CG and EG are smaller and often non-significant. | Effect sizes are small and p-values non-significant for some negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, boredom), as shown in Table 7c. | APT feedback helps students cope with negative states, but improvements are more subtle than positive emotions. |

| Feedback–emotion associations (Table 8a,b) | Strong links between specific feedback items and emotional states within EG. | Significant Pearson correlations between cognitive/affective feedback and emotional items, reported in Table 8a,b. | Emotional engagement is systematically related to both cognitive and affective feedback components. |

| Engagement profiles (PCA + clustering) | Two dominant profiles: one highly engaged with positive feedback and one with lower engagement and more negative emotions. | PCA and cluster analysis identify two main patterns of emotional engagement, as described in Section 3.2.2 and related figures. | APT feedback contributes to differentiating high-engagement vs. low-engagement student profiles. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arguedas, M.; Daradoumis, T.; Caballe, S.; Conesa, J.; Ortega-Ochoa, E. Exploring the Impact of Affective Pedagogical Agents: Enhancing Emotional Engagement in Higher Education. Computers 2025, 14, 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120542

Arguedas M, Daradoumis T, Caballe S, Conesa J, Ortega-Ochoa E. Exploring the Impact of Affective Pedagogical Agents: Enhancing Emotional Engagement in Higher Education. Computers. 2025; 14(12):542. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120542

Chicago/Turabian StyleArguedas, Marta, Thanasis Daradoumis, Santi Caballe, Jordi Conesa, and Elvis Ortega-Ochoa. 2025. "Exploring the Impact of Affective Pedagogical Agents: Enhancing Emotional Engagement in Higher Education" Computers 14, no. 12: 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120542

APA StyleArguedas, M., Daradoumis, T., Caballe, S., Conesa, J., & Ortega-Ochoa, E. (2025). Exploring the Impact of Affective Pedagogical Agents: Enhancing Emotional Engagement in Higher Education. Computers, 14(12), 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120542