1. Introduction

The rapid progress of generative AI and large language models (LLMs) has redefined machine intelligence benchmarks, producing outputs often indistinguishable from those of humans. Transformer architectures and retrieval-augmented pipelines now provide contextual awareness and access to vast information sources, giving experts tools no single individual could fully master [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Yet, despite their utility, these systems remain architecturally constrained. They operate primarily through statistical correlations over token sequences, with shallow or externally bolted-on memory, and are guided by no intrinsic purpose or ethical framework [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Knowledge, when present, is encoded as opaque weights and prompt engineering rather than as an explicit, evolvable substrate. As a result, such systems cannot autonomously distinguish truth from falsehood, meaning from noise, nor reliably align their operations with system-level goals without continuous human supervision and ad hoc governance layers.

Agentic AI frameworks attempt to overcome these limits by wrapping LLMs with planning, memory, and feedback loops, enabling them to execute multi-step tasks and interact with tools [

11,

12]. While this increases utility, the underlying substrate remains the same: a correlation-based, Turing-paradigm engine, orchestrated by external scripts and controllers. As the number of interacting agents grows, so does the risk of misalignment, error cascades, and uncontrolled feedback [

13]. The central architectural question remains unresolved: who or what enforces global coherence across these agents over time? Without an intrinsic control plane and persistent knowledge blueprint, agentic AI risks presenting the appearance of autonomy while depending heavily on human managers or orchestration software to maintain order.

1.1. The Problem of Coherence Debt

Enterprises today increasingly delegate high-stakes decisions—from loan approvals to medical diagnostics—to AI-driven workflows. However, three structural deficits persist in current LLM- and ML-centric systems:

Brittleness: Systems learn slowly and forget context, failing when data distributions drift (e.g., a model trained in 2020 failing in 2024).

Opacity: “Black box” decisions lack traceable rationales and counterfactuals, creating regulatory friction and eroding trust.

Governance Friction: Safety, compliance, and ethics are often “bolted on” as external rules, dashboards, and guardrails rather than designed into the architecture.

We characterize these failures as symptoms of Coherence Debt: the accumulated mismatch between (i) what the system is supposed to be doing (its purposes, policies, and constraints) and (ii) what its underlying computational architecture is actually optimized for (local pattern prediction under shifting conditions). Coherence debt grows when knowledge, memory, and governance are externalized into scripts, documents, and human processes instead of being treated as first-class structural elements of the computing system.

1.2. Lessons from Biology

Biological systems suggest a different path. A multicellular organism is itself a society of agents—cells—that achieve coherent function through communication, feedback loops, and genomic instructions that encode shared purposes such as survival and reproduction. The genome provides a persistent architectural blueprint that coordinates local interactions, constrains possible behaviors, and supports lifelong adaptation. This intrinsic teleonomy prevents chaos and sustains resilience under perturbation [

14,

15,

16]. For AI, the analogy is clear: a swarm of software agents or microservices is insufficient without system-wide memory, goals, and self-regulation. Intelligent beings, like biological systems, require a persistent blueprint that aligns local actions with global purpose and can evolve without losing identity.

1.3. Emerging Theoretical Frameworks Suggesting Post-Turing Computing Models

Theoretical work in information science and computation provides foundations for such a blueprint. Burgin’s General Theory of Information (GTI) expands information beyond Shannon’s syntactic model to include both ontological (structural) and epistemic (knowledge-producing) aspects [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Building on GTI, the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT) identifies a key limitation of the Turing paradigm: the separation of the computer from the computed—the machine from the knowledge structures it manipulates [

23,

24]. BMT proposes structural machines that unite runtime execution with persistent knowledge structures, enabling self-maintaining and adaptive computation. Deutsch’s epistemic thesis complements this by defining genuine knowledge as extendable, explainable, and discernible—criteria largely absent from today’s black-box AI models [

25]. Finally, Fold Theory (Hill) emphasizes recursive coherence between observer and observed, reinforcing the idea that computation must integrate structure, meaning, and adaptation into a single evolving process [

26,

27,

28].

Taken together, these perspectives point to a new model of computation in which information, knowledge, and purpose are intrinsic to the act of computing, not external annotations. In such systems, coherence is engineered at the architectural level rather than patched after deployment.

1.4. Mindful Machines with Autopoietic and Metacognitive Behaviors

Building on this synthesis, we introduce Mindful Machines: distributed software systems that integrate autopoietic (self-regulating) and meta-cognitive (self-monitoring) behaviors as native architectural features. Their operation is guided by a Digital Genome—a persistent, knowledge-centric code that encodes functional goals, policies, architectural patterns, and ethical constraints [

29]. Instead of treating the model as a static artifact inside a pipeline, the Digital Genome defines and evolves the structure of the system itself: which services exist, how they interact, what health and governance checks they obey, and how they adapt under change.

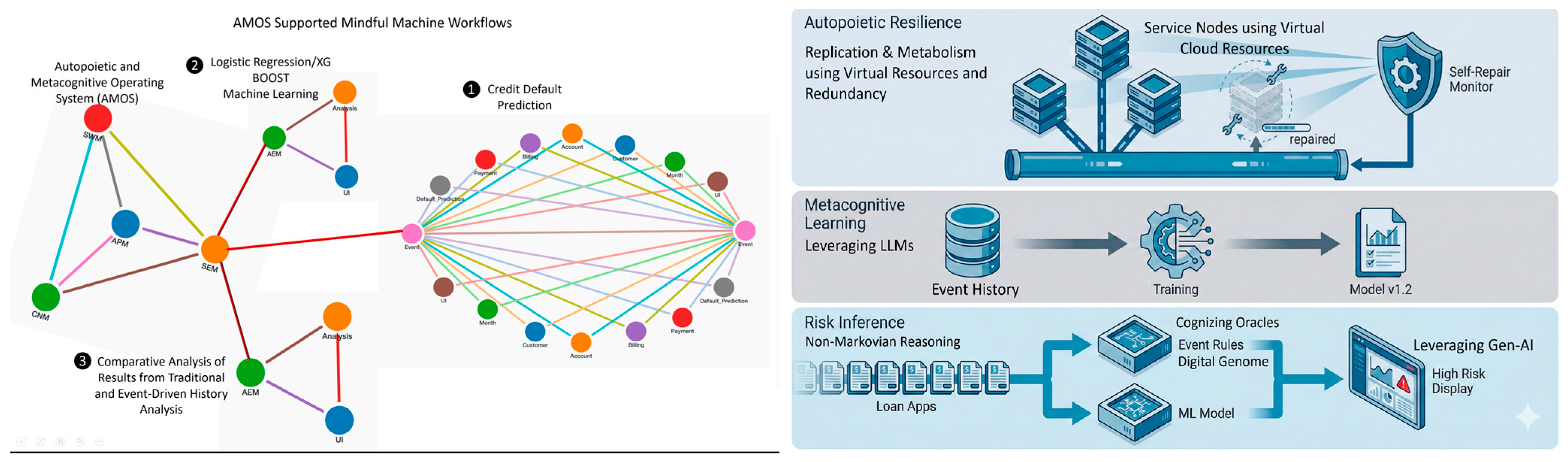

To operationalize this vision, we present the Autopoietic and Meta-Cognitive Operating System (AMOS). Unlike conventional orchestration platforms (e.g., Kubernetes) that primarily manage resources and deployment, AMOS functions as a knowledge-driven control plane. It provides:

Self-deployment, self-healing, and self-scaling via redundancy and replication across heterogeneous cloud infrastructures, guided by explicit health and policy rules rather than ad hoc scripts.

Semantic and episodic memory implemented in graph databases to preserve both structural knowledge (rules, ontologies, Digital Genome) and event histories (transactions, failures, recoveries), enabling non-Markovian reasoning and traceability.

Cognizing Oracles that interrogate these memories to validate knowledge, test decisions against constraints, and regulate decision-making with transparency, explainability, and critique-then-commit gates.

We evaluate this architecture through a case study: re-implementing the classic credit-default prediction task discussed in Klosterman’s book [

30] as a distributed, knowledge-centric service network managed by AMOS. In the conventional baseline, Logistic Regression is embedded in a static ML pipeline: a fixed feature set, a trained model artifact, and deployment scripts that must be manually updated as conditions change. In contrast, our Mindful Machine implementation decomposes the application into containerized services whose structure and interactions are governed by the Digital Genome and AMOS. This allows the system to:

remain resilient under failure (autopoiesis through self-healing and live migration),

provide auditable decision provenance (event-driven, graph-based audit trails), and

support real-time adaptation to behavioral changes (e.g., updating rules, thresholds, or model variants without redeploying the entire stack).

The contributions of this paper are fourfold:

We articulate coherence debt as an architectural problem and ground the design of Mindful Machines in a synthesis of GTI, BMT, Deutsch’s epistemic thesis, and Fold Theory.

We describe the architecture of AMOS and its integration of autopoietic and meta-cognitive behaviors around a persistent Digital Genome.

We demonstrate feasibility by deploying a cloud-native loan default prediction system composed of containerized services governed by AMOS, contrasting it with a textbook Logistic Regression pipeline.

We show how this paradigm advances transparency, adaptability, and resilience—and thus reduces coherence debt—beyond conventional machine learning and LLM-centric pipelines.

In doing so, this paper positions Mindful Machines as a pathway toward sustainable, knowledge-driven distributed software systems—bridging the gap between symbolic reasoning, statistical learning, and trustworthy autonomy.

In

Section 2, we elaborate the theoretical foundations and formalize coherence as an architectural property.

Section 3 presents the system architecture of AMOS and its implementation.

Section 4 describes the AMOS-managed loan default prediction application and contrasts it with the conventional ML pipeline.

Section 5 discusses the experimental observations and comparative results, and

Section 6 concludes with implications, limitations, and directions for further research on coherence-centric AI.

2. Theories and Foundations of the Mindful Machines

The architecture of Mindful Machines represents a paradigm shift away from conventional, statistically centered, correlation-based artificial intelligence (AI). This new computational model requires a deep theoretical grounding to justify its architectural changes and unique operational features, such as intrinsic self-regulation and semantic transparency. This section analyzes four foundational theories—General Theory of Information (GTI), the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT), Deutsch’s Epistemic Thesis (DET), and Fold Theory (FT)—and shows how their synthesis motivates, and almost forces, the design of the Autopoietic and Meta-Cognitive Operating System (AMOS) and its application to credit default prediction.

The limitations of the Turing paradigm—where computation is treated as blind, closed symbol manipulation—become apparent when systems must provide adaptability, resilience, and genuine explainability. In a credit default prediction setting, these limits show up as static models that degrade under drift, brittle pipelines, and “black box” scores that are difficult to regulate. The transition to a new computing model is driven by four theoretical pillars that collectively redefine information, knowledge, and the relationship between the computer and the computation—and thereby change how we structure and operate a credit-risk system.

2.1. General Theory of Information (GTI)

Mark Burgin’s General Theory of Information (GTI) provides the first conceptual shift necessary for Mindful Machines. GTI broadens the notion of information beyond Shannon’s syntactic, statistical view. Built on axioms and mathematical models (e.g., information algebras and category-theoretic operators), GTI defines information as a triadic relation involving a carrier, a recipient, and the conveyed content.

A central contribution of GTI is the explicit distinction between ontological information and epistemic information. Ontological information refers to the structural properties and dynamics inherent in material or formal systems, governed by physical or logical laws. Epistemic information is the knowledge produced when these structures are accessed and interpreted by a cognitive system.

For cognitive software design, GTI reframes information from a passive data stream to an active organizing principle. Knowledge is not just “more data” but a more advanced structural state, formed when external ontological structure is internalized as epistemic content. This directly supports a shift from data-centric to knowledge-centric architectures.

In Mindful Machines, this shift is realized in AMOS through the Semantic Memory Layer, which stores ontologies, rules, and policies as first-class objects. Instead of treating transaction records and features as raw inputs, AMOS maintains explicit knowledge structures (e.g., customer states, repayment habits, product rules) that guide how new information is interpreted. This reduces reliance on brute-force statistical processing and supports more energy-proportional, targeted computation, closer to how biological systems use prior structure to minimize waste.

Implications for credit default prediction.

Under a GTI lens, the credit default application no longer treats monthly bills and payments as flat rows in a table. Each event (billing, payment, delinquency, restructuring) is ontological information about the evolving customer–account relationship. The Semantic Memory Layer turns these events into epistemic structures: risk trajectories, behavioral states, and policy contexts represented in a graph. Instead of training a model once on PAY_1–PAY_6 and freezing it, the system maintains an evolving knowledge base about customers and products, enabling more precise, context-aware default predictions that adapt as new events arrive.

2.2. Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT)

Building on GTI’s ontological and epistemic distinctions, the Burgin–Mikkilineni Thesis (BMT) addresses a core architectural limitation of classical computation: the rigid separation of the computer (hardware and runtime) from the computed (data, programs, and knowledge structures). In the Turing machine model, computation is closed, context-free, and semantically blind. This is adequate for well-defined algorithms but ill-suited for systems that must maintain themselves, adapt, and remain explainable in changing environments.

BMT proposes Structural Machines, in which the computer and computation form a dynamically evolving unity. The system’s structure—its components, connections, and governing rules—is itself part of what is computed and updated. This enables autopoietic computation: the ability to sustain, regenerate, and adapt one’s own internal structure rather than only transforming external tapes or data streams. BMT argues that efficient autopoietic and cognitive behavior requires such structural machines.

In Mindful Machines, the engineering realization of this requirement is the Digital Genome (DG). The DG is a persistent, knowledge-centric blueprint that encodes goals, structural rules, and ethical constraints. It acts as explicit self-knowledge for the system: describing what services exist, how they should be deployed, how they monitor each other, and which policies they must follow. This encoding is what allows AMOS to exhibit autopoietic behaviors such as self-deployment, self-healing, live migration, and elastic scaling.

By dissolving the classical boundary between “machine” and “meaning,” BMT supports distributed environments where local services have intrinsic guidance about how to maintain global coherence. Rather than relying solely on external orchestration scripts and human operators, the system’s structure is co-determined by its Digital Genome.

Implications for credit default prediction.

In a conventional pipeline, credit default prediction is a separate artifact: a logistic regression model implemented in code, trained offline, and then “plugged into” deployment scripts. The infrastructure that runs it (containers, databases, schedulers) is treated as independent plumbing. Under BMT, the credit-risk system becomes a structural machine: the Digital Genome encodes not only the model but also the service topology (e.g., data ingestion, feature construction, risk scoring, notification), the health rules for each service, and the scaling policies. When a node fails, traffic spikes, or a new regulatory rule appears, AMOS can reconfigure this structure—migrating services, updating rules, or swapping model variants—without human redesign. Credit default prediction is no longer a single model but an evolving, self-maintaining structure.

2.3. Deutsch’s Epistemic Thesis (DET)

David Deutsch’s work provides a quality standard for knowledge that links epistemology, physics, computation, and evolution. He argues that genuine knowledge is characterized by being extendable, explainable, and discernible. Knowledge advances through error correction and the creation of good explanations—those that are hard to vary while still accounting for the phenomena.

This thesis is a direct critique of many current machine learning models. Even when highly accurate, conventional ML and deep networks often fail Deutsch’s criteria: their internal representations are opaque, difficult to extend without retraining from scratch, and do not provide explanations in a human-interpretable sense. They offer predictions but not structured, scrutinizable reasons.

For Mindful Machines, especially in high-stakes domains such as finance and healthcare, this epistemic standard is not optional. Transparency and the ability to trace decisions back to principles become design requirements, not add-ons. AMOS operationalizes this through Cognizing Oracles and Episodic Memory. Cognizing Oracles consult the Digital Genome and Semantic Memory to check proposed actions against rules, policies, and ethical constraints. Episodic Memory records event histories and decisions, forming an audit trail that connects each output to its context and justification.

This combination turns predictions into knowledge assets: each decision can be interrogated, critiqued, and revised, satisfying Deutsch’s emphasis on explanation and error correction.

Implications for credit default prediction.

In a textbook logistic regression implementation, a customer’s default score is produced as a probability with little native context. Regulators and risk officers may see coefficients and ROC curves, but they do not receive a living, causal narrative. Under DET-inspired architecture, every credit decision is accompanied by a trace: which events (late payments, utilization changes, restructuring), which rules (risk thresholds, product policies), and which model variants contributed to the final outcome. Cognizing Oracles can reject or flag decisions that violate policy (e.g., fairness constraints, regulatory caps) or that lack sufficient evidential support. Thus, credit default prediction moves from “a number from a model” to an explainable, auditable judgment grounded in structured knowledge and explicit policies.

2.4. Fold Theory (FT)

Skye L. Hill’s Fold Theory (FT) provides the metaphysical and dynamical framework necessary to support the continuous evolution described by GTI and BMT. FT emphasizes recursive coherence between ontological structures (the environment and system state) and epistemic structures (the system’s knowledge), arguing that they are “folded together” in the ongoing maintenance of reality.

In Fold Theory, complex systems maintain integrity through continuous, local recursive updates; global stability is the result of many small, coherent adjustments rather than static design. Concepts such as coherence sheaves formalize how local consistencies can be integrated into robust global structures. Time and fields are treated as emergent from coherence processes, rather than fixed backgrounds.

Applied to computation, FT suggests that a system’s architecture must support continuous, topology-changing adaptation: reconfiguring connections, roles, and flows while preserving a coherent identity. This directly informs the need for active self-maintenance managers in AMOS. While BMT tells us that we need a structural machine, FT describes how that machine must operate under perpetual change.

AMOS’s Autopoietic Layer—implemented via components such as the Application Process Manager (APM), Cloud Network Manager (CNM), and Software Workload Manager (SWM)—is the engineering response to FT. These managers observe local events (failures, spikes, new patterns), adjust local structure (restart, replicate, reroute, rescale), and ensure that such changes remain consistent with the Digital Genome and global policies. In a distributed society of agents, this prevents local disruptions from escalating into systemic failure.

Implications for credit default prediction.

Traditional credit models are typically updated in batch cycles (e.g., quarterly or annually), with significant manual effort. They are poorly suited to environments where customer behavior, economic conditions, and regulations shift continuously. Under FT-informed AMOS, the credit default prediction system becomes a continuously adapting fabric. If a segment of customers begins to behave differently (e.g., new repayment patterns after a policy change), local services responsible for that segment can adjust thresholds, trigger alternative models, or reweight rules—changes that APM, CNM, and SWM propagate while preserving global constraints. Failures in one region or cloud provider can be absorbed without system-wide outages. Credit risk management thus becomes an ongoing, coherent adaptation process rather than a series of disjoint model releases.

2.5. Beyond Turing Computing and Blackbox

Taken together, GTI, BMT, DET, and FT transform credit default prediction from a static classification task into a knowledge-centric, autopoietic service. GTI reframes data as structured information and knowledge; BMT requires that this knowledge co-define the system’s architecture via a Digital Genome; DET demands that predictions be explainable and auditable; and FT ensures that structure and knowledge co-evolve coherently over time. AMOS is the concrete operating system that embodies this synthesis, and the credit default case study shows how these theoretical commitments change both the form and the behavior of a real-world application.

3. System Architecture and the Autopoietic and Meta-Cognitive Operating System (AMOS)

The Autopoietic and Meta-Cognitive Operating System (AMOS) provides an execution environment for Mindful Machines. Unlike a monolithic operating system or a conventional cloud orchestrator, AMOS functions as a distributed, knowledge-driven control plane that instantiates, coordinates, and sustains services derived from the Digital Genome (DG). The DG acts as a machine-readable blueprint of operational knowledge: it encodes functional goals, non-functional requirements, best-practice policies, and global constraints. From this blueprint, AMOS seeds and maintains a knowledge network in a graph database, structured as both associative memory (schemas, rules, policies) and event-driven history (transactions, failures, recoveries).

Application design in this paradigm begins with the Digital Genome, not with a model or a pipeline script. The DG is the application designer’s interface for specifying the desired functional entities as containerized services (cognitive “cells”) with well-defined inputs, behaviors, and outputs. Crucially, the DG also encodes a knowledge network configuration, linking these entities via shared process knowledge and policies (e.g., risk thresholds, compliance rules, escalation paths). This configuration—describing both the nodes and their interdependencies—is then consumed by AMOS as a schema of operational knowledge.

The Autopoietic Process Manager (APM) uses this DG schema to manage deployment. It interfaces with IaaS and PaaS resources from cloud providers, exploiting their self-service APIs to instantiate the containerized services, assign resources, and establish the initial network topology. The Cognitive Network Manager (CNM) translates the DG’s knowledge network configuration into dynamic runtime service connections: it routes requests, rewires workflows, and adapts communication paths in response to changing loads, failures, or policy updates. Together, APM and CNM realize the BMT requirement that structure and computation co-evolve, rather than leaving topology and execution as separate concerns.

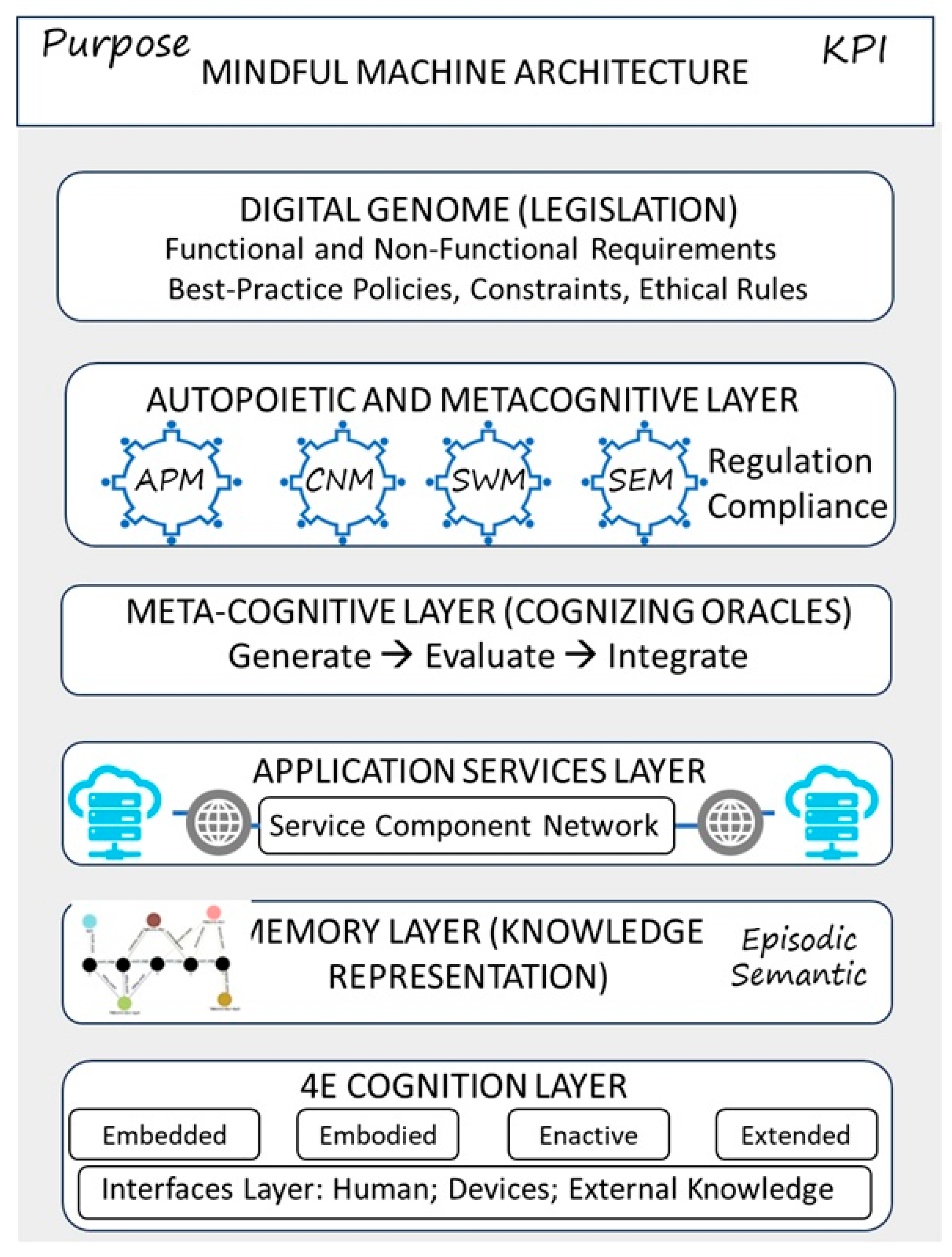

Figure 1 summarizes the layered AMOS architecture:

Digital Genome Layer—encodes goals, schemas, and policies as prior knowledge that constrains and guides system behavior.

Autopoietic Layer (AMOS Core)—Implements resilience and adaptation through core managers:

- ○

APM (Autopoietic Process Manager): Deploys services, replicates them when demand rises, and guarantees recovery after failures.

- ○

CNM (Cognitive Network Manager): Manages inter-service connections, dynamically rewiring workflows to maintain coherence under changing conditions.

- ○

SWM (Software Workflow Manager): Monitors execution integrity, detects bottlenecks, and coordinates reconfiguration across workflows.

- ○

Policy and Knowledge Managers: Interpret DG rules, enforce compliance, and ensure traceability across all adaptations.

Meta-Cognitive Layer—Cognizing Oracles oversee workflows, monitor inconsistencies, validate external knowledge (e.g., new models, rule updates), and enforce explainability and critique-then-commit gates.

Application Services Layer—A network of distributed services (cognitive “cells”) that collaborate hierarchically to execute domain-specific functions such as feature construction, risk scoring, alerting, and reporting.

Knowledge Memory Layer—Maintains long-term learning context through:

- ○

Semantic Memory: Rules, ontologies, product definitions, and encoded policies.

- ○

Episodic Memory: Event-driven histories capturing interactions, failures, interventions, and decision traces.

Implications for credit default prediction.

In a conventional credit default implementation, the operating system and orchestrator are largely invisible: a static Logistic Regression model is trained offline, wrapped in a simple service or script, and deployed to production. Adaptation requires manual retraining, redeployment, and reconfiguration of infrastructure. Under AMOS, by contrast, the Digital Genome explicitly encodes the credit-risk services (data ingestion, feature engineering, model variants, risk thresholds, notification channels), their dependencies, and the governing policies (e.g., regulatory constraints, fairness rules). APM and CNM ensure that these services are self-deploying, self-healing, and elastically scalable; SWM maintains workflow integrity as traffic patterns or user segments change; and Cognizing Oracles use Semantic and Episodic Memory to audit every decision and trigger model or policy updates when behavior drifts. Thus, credit default prediction is no longer a single model embedded in a brittle pipeline but a living, autopoietic service network whose structure and behavior are continuously aligned with the knowledge encoded in the Digital Genome.

3.1. Service Behavior and Global Coordination

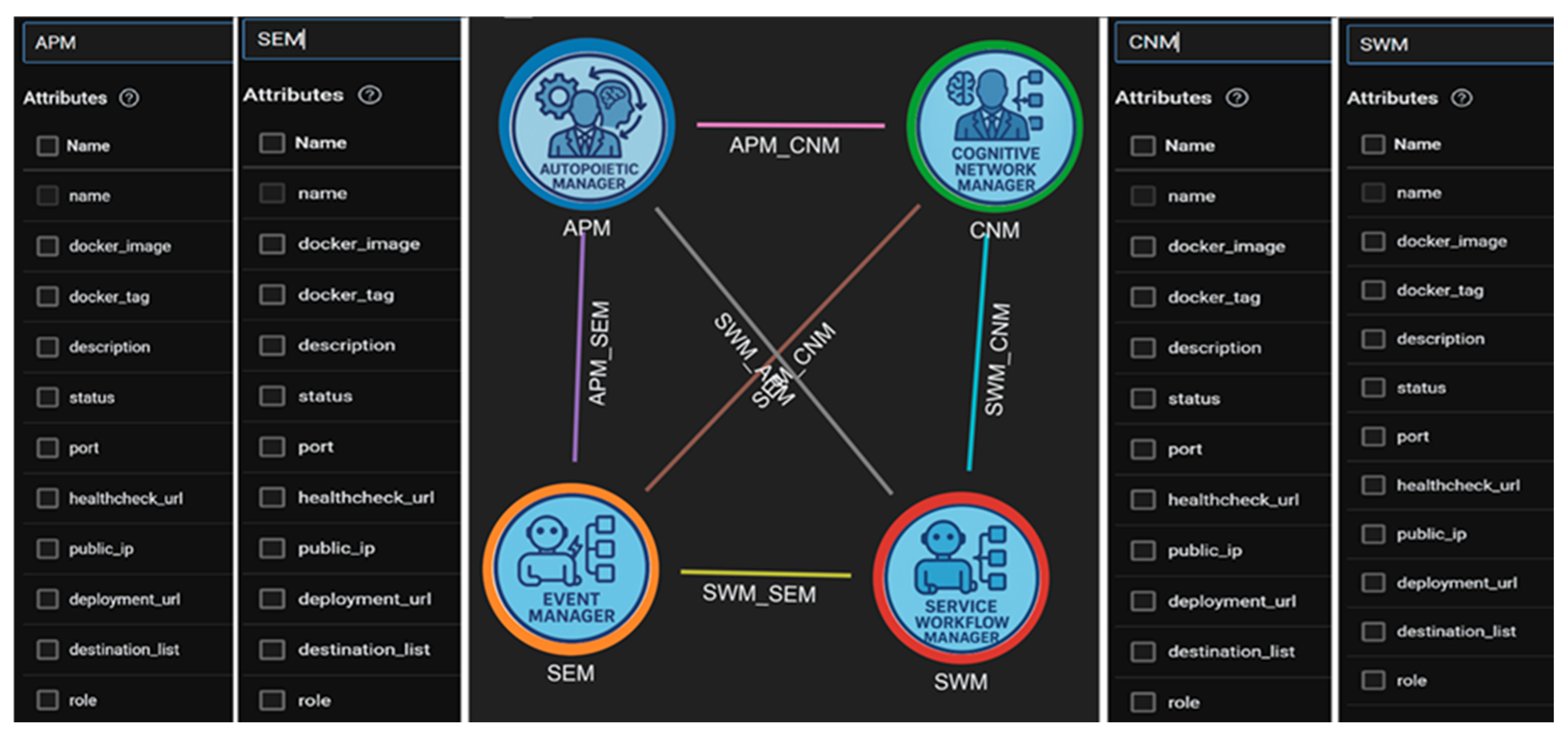

The core mechanisms for self-regulation are explicitly defined by the AMOS Layer managers:

Autopoietic Process Manager (APM): This manager is responsible for the system’s structural integrity. It initializes the system, determining the placement and resource allocation for containerized services across heterogeneous cloud infrastructure (IaaS/PaaS) based on DG constraints. Crucially, the APM ensures resilience by actively executing automated fault recovery and elastic scaling—replicating services when demand rises or guaranteeing recovery after failures.

Cognitive Network Manager (CNM): The CNM governs the system’s dynamic coherence. It manages the inter-service connections based on the DG’s knowledge blueprint and is capable of dynamically rewiring workflows under changing conditions. Together with the APM, it configures the network structure to maintain Quality of Service (QoS) using policy-driven mechanisms like auto-failover or live migration, guided by Recovery Time Objective (RTO) and Recovery Point Objective (RPO) metrics.

Software Workflow Manager (SWM): The SWM ensures the logical flow of computation. It monitors execution integrity, detects bottlenecks, and coordinates necessary reconfigurations, linking the state changes of services back to the system’s overall structural coherence.

Policy Manager: This manager interprets DG rules, enforcing compliance and ensuring traceability. For instance, if service response time exceeds a specified threshold, the Policy Manager directs the APM to trigger auto-scaling to reduce latency, utilizing best-practice policies derived from the system’s history.

Each service in AMOS behaves like a cognitive cell with the following properties:

Inputs/Outputs: Services consume signals, events, or data, and produce results, insights, or state changes guided by DG knowledge.

Shared Knowledge: Services update semantic and episodic memory, ensuring global coherence, similar to biological signaling pathways.

Sub-networks: Services form functional clusters (e.g., billing or monitoring), analogous to specialized tissues.

Global Coordination: Sub-networks are orchestrated by AMOS managers to ensure system-wide goals are preserved.

Key properties of this design include:

Local Autonomy: Services act independently, improving resilience.

Global Coherence: Shared memory and DG constraints ensure alignment.

Evolutionary Learning: Services adapt to improve efficiency and workflows.

Collectively, these functions enable self-deployment, self-healing, self-scaling, knowledge-centric operation, and traceability, distinguishing AMOS from conventional orchestration systems (

Figure 2).

3.2. Implementation: Distributed Loan Default Prediction

To demonstrate feasibility, we re-implemented the loan default prediction problem from Klosterman [

30] using AMOS. The original task—predicting whether a customer will default based on demographics and six months of credit history—was treated as a conventional supervised learning problem on a static dataset of 30,000 customers. A logistic regression model was trained once on pre-engineered features (e.g., PAY_1–PAY_6) and then deployed as a single predictive artifact.

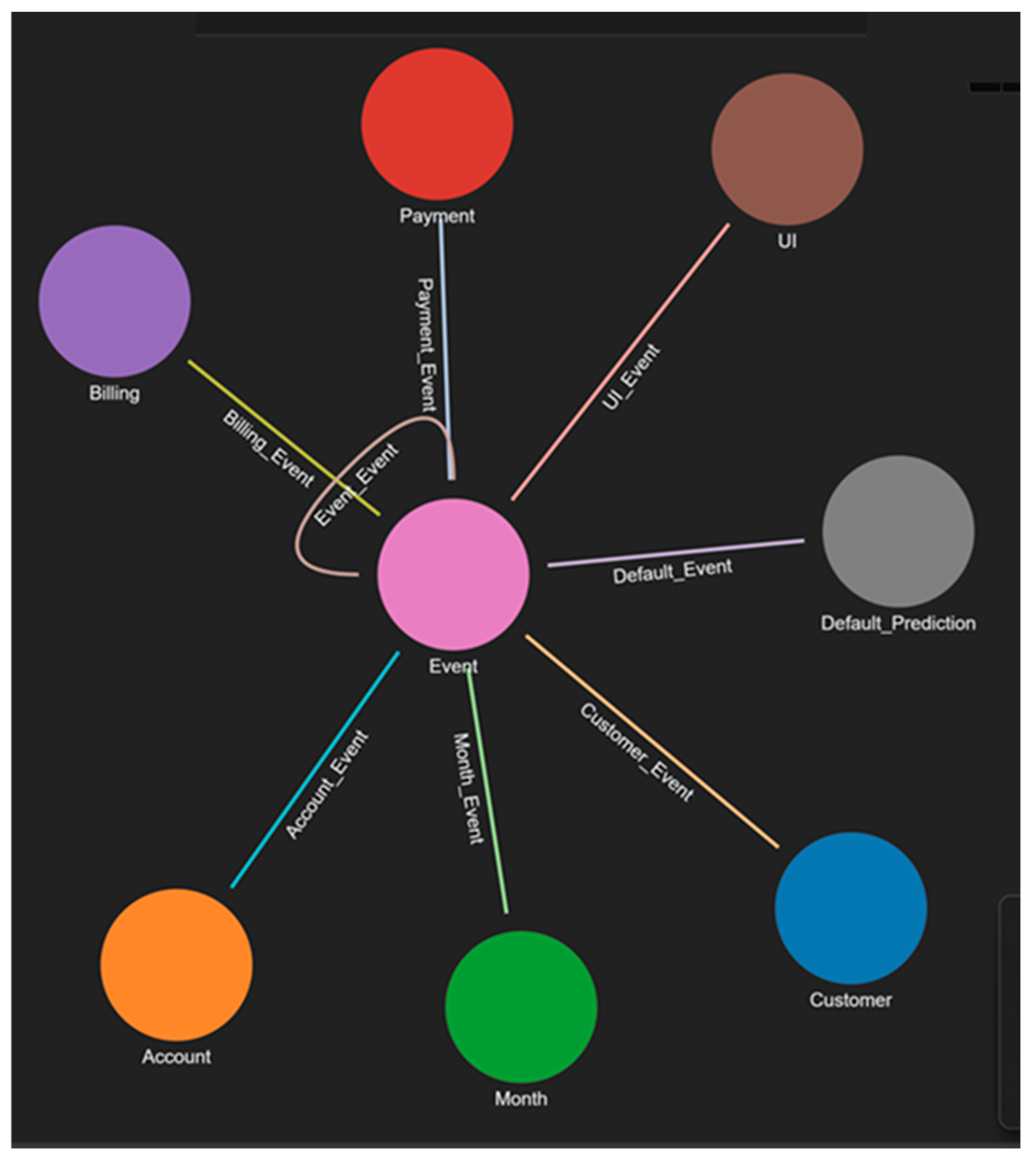

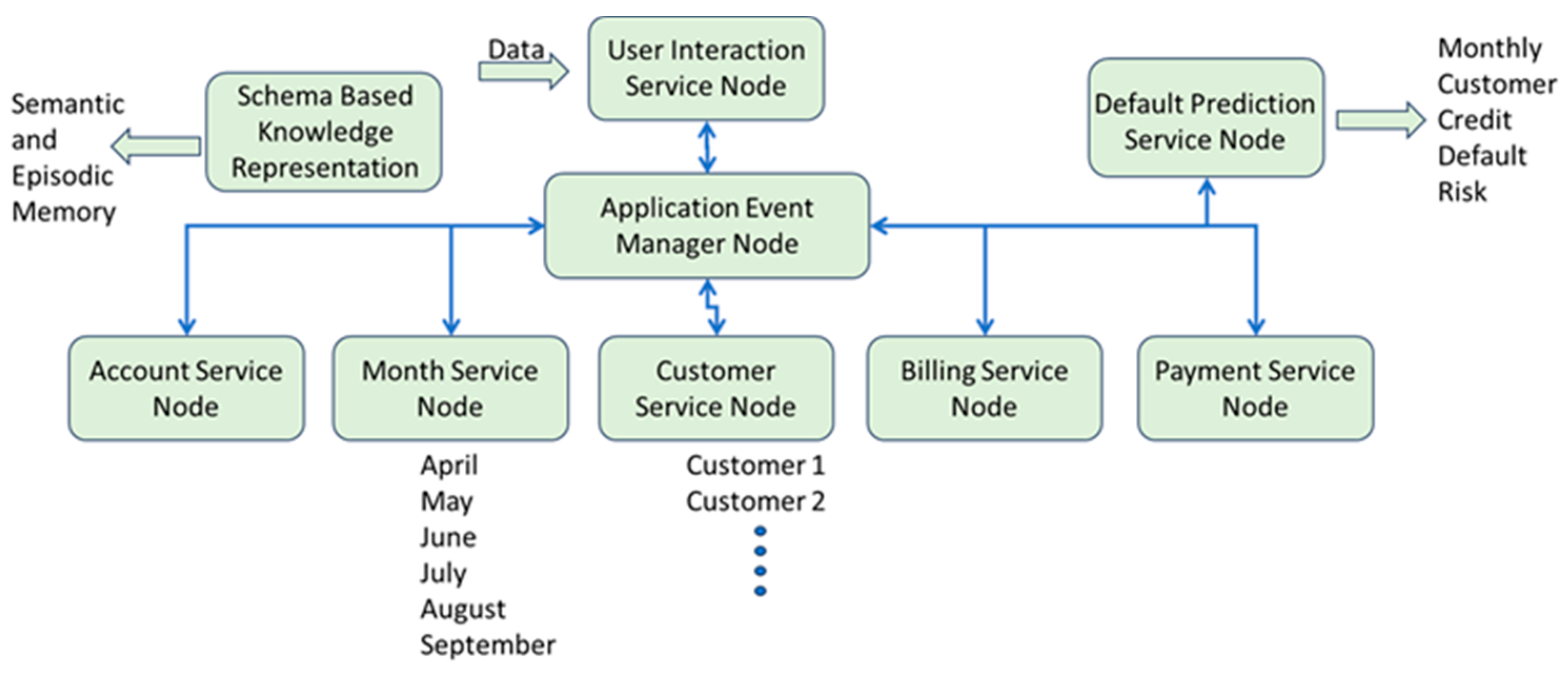

In the Mindful Machine paradigm, the same problem is reframed as an event-driven, knowledge-centric service network rather than a single model endpoint. AMOS decomposes the application into containerized microservices that communicate via HTTP and persist events in a graph database. The main components are:

Cognitive Event Manager—Anchors the data plane and knowledge plane. It records both episodic memory (events such as bills, payments, and defaults) and semantic memory (schemas, rules, and policies), implementing the GTI/BMT view of knowledge as structured, persistent information.

Customer, Account, Month, Billing, and Payment Services—Model financial behavior as event-driven processes. Each service is a cognitive “cell” responsible for a specific aspect of the customer–account lifecycle (e.g., issuing bills, recording payments, updating delinquency status).

UI Service—Ingests data (batch or streaming), initiates workflows, and distributes workloads to domain services, decoupling user interaction from internal structure.

Default Prediction Service—Computes next-month default risk using rule-based or learned models (including logistic regression), but now as one component in a larger knowledge framework. Its outputs are linked to event histories and policies, making them auditable and explainable.

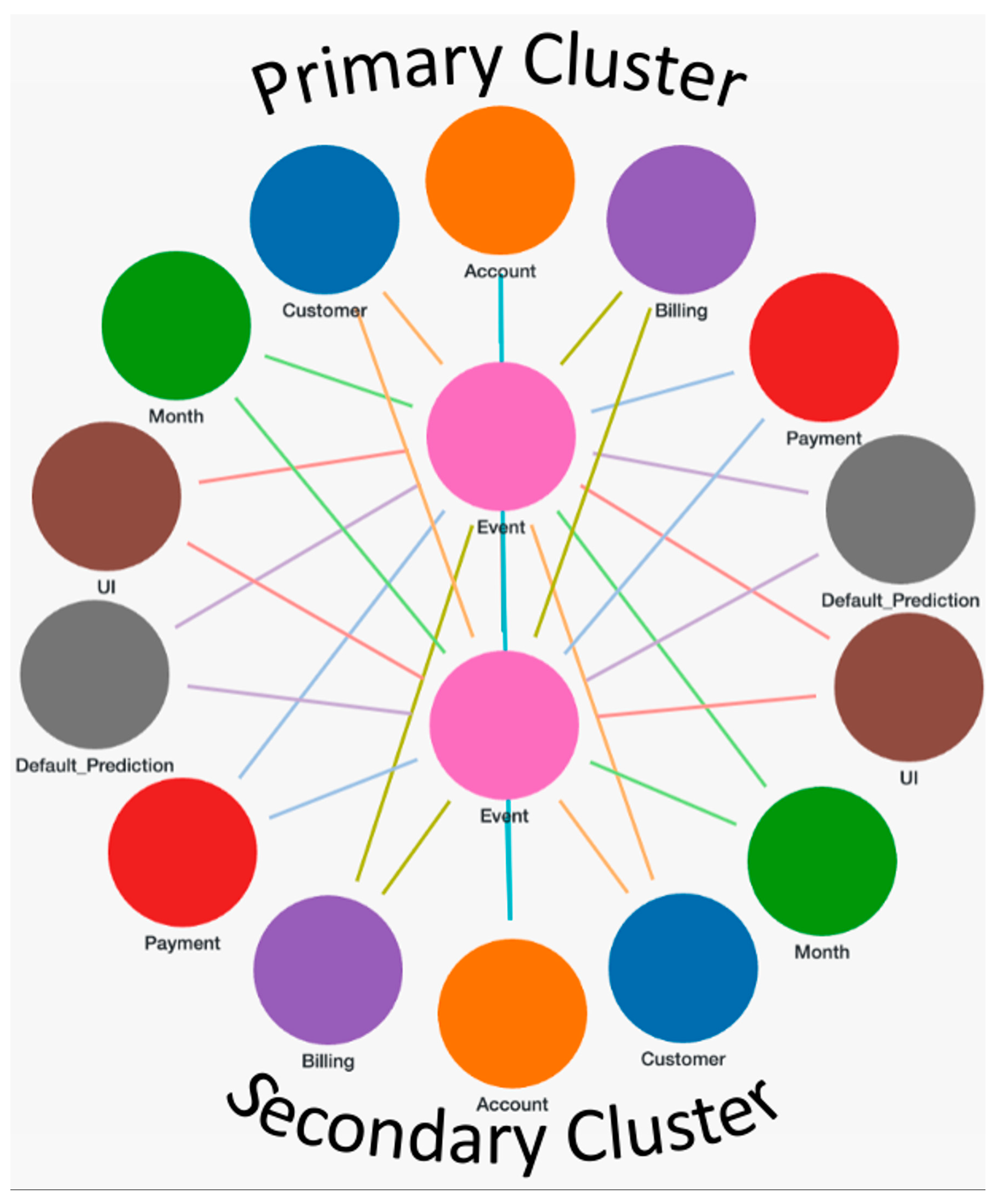

Figure 3 shows the schema for the default loan application services. Each node represents a process with defined inputs and outputs, forming an event-driven service network managed by AMOS.

This event-sourced design enables reproducibility, explainability, and controlled evolution. Every prediction is grounded in a causal chain that can be reconstructed from the graph database, for example:

Instead of a single model frozen in time, AMOS turns credit default prediction into a living process whose structure, memory, and policies are explicit and evolvable.

3.3. Demonstration of Autopoietic and Meta-Cognitive Behaviors

The distributed system is implemented in Python 3.13 with TigerGraph as the graph database supporting semantic and episodic memory. AMOS manages container deployment on cloud infrastructure (IaaS/PaaS), providing autopoietic functions such as self-repair via health checks, policy-driven restarts, and elastic scaling. The Cognitive Event Manager acts as the memory backbone, allowing services to reason over both structure (who is connected to whom, under what policies) and history (what has happened, in what order).

At runtime, the service network exhibits meta-cognitive behaviors that go beyond a conventional ML pipeline:

Services monitor repayment code distributions, utilization patterns, and error rates. When they detect distributional drift (e.g., a new pattern of late payments in a customer segment), they record this in episodic memory and signal Cognizing Oracles or policy managers.

The Default Prediction Service can switch between rule-based baselines and logistic regression (or alternative models) when performance degrades or when policies change. AMOS coordinates this transition: APM and CNM adjust service instances and routing; SWM ensures workflows remain coherent; Policy Managers ensure that changes remain within DG constraints (e.g., regulatory or fairness rules).

Every credit decision can be explained via event provenance queries:

Why was this customer labeled at risk? The system can answer by traversing the graph—showing the history of billing and payment events, detected anomalies, applied rules, and chosen model variant—thereby meeting Deutsch’s requirement for discernible, extendable knowledge rather than opaque correlation.

This transforms a conventional ML pipeline into a Mindful Machine: a distributed, autopoietic system with introspection, transparency, and resilience. The credit default application becomes a concrete demonstration of how the GTI/BMT/DET/FT-informed architecture pays down coherence debt:

Autopoiesis: Self-deployment, self-healing, and self-scaling of risk-related services.

Meta-cognition: Monitoring its own behavior, detecting drift, and switching logic under governance.

Knowledge-centric operation: Decisions grounded in a persistent Digital Genome, semantic rules, and episodic histories rather than an isolated model file.

Traceability: End-to-end provenance for every prediction, enabling auditability and regulatory alignment.

Figure 4 presents the workflow diagram of the GTI/DG-based credit-default implementation on AMOS. Services (with ports) form the control and data planes; the Cognitive Event Manager persists events and entities to the graph; the Default Prediction Service consumes the latest month’s events to infer next-month outcomes. Replication of service nodes, their communication paths, and redundancy of virtual containers determine the system’s resilience and coherence under load and failure.

4. What We Learned from the Implementation

In developing the loan default prediction application on the AMOS platform, we demonstrated how a conventional machine learning task can be restructured as a knowledge-centric, autopoietic system.

The application was decomposed into modular and distributed services—including Customer, Account, Billing, Payment, and Event—each designed to perform a single, well-defined function. This modularization allowed the system to inherit the resilience and adaptability of distributed architectures.

Both functional requirements (e.g., prediction logic, data handling, feature generation) and non-functional requirements (e.g., performance, resilience, compliance, traceability) were encoded in the Digital Genome (DG). By doing so, the DG not only served as a design blueprint but also provided a persistent source of policies and constraints to regulate runtime behavior.

The system integrated two complementary forms of memory: associative memory, capturing patterns of past behavior, and event-driven history, recording temporal sequences of interactions. Specifically, the Cognitive Event Manager persists this structural knowledge—both ontologies/rules (Semantic Memory) and event histories (Episodic Memory)—within a high-performance graph database, enabling complex, graph-based queries for real-time validation and tracing. Together, these memory structures enabled continuous learning and made decision trails auditable over time.

Autopoietic and cognitive regulation were maintained through the AMOS core managers. The Autopoietic Process Manager (APM) ensured automatic deployment and elastic scaling of services; the Cognitive Network Manager (CNM) preserved inter-service connectivity under changing conditions; and the Software Workflow Manager (SWM) guaranteed logical process execution and recovery after disruption. These managers collectively provided the system with self-healing and self-sustaining properties.

Furthermore, the Cognizing Oracles and the nature of the prediction service directly address the epistemic requirements for trustworthiness. The Default_Prediction Service utilizes transparent rule-based logic such as the predict_next_pay function. This logic converts numerical prediction codes into descriptive textual representation. This mechanism transforms the prediction from an opaque correlation into a discernible, auditable, and rule-based decision asset, satisfying Deutsch’s criteria for knowledge by providing transparent justification for every decision.

Appendix A discusses the credit card default prediction in more detail.

Finally, large language models (LLMs) were leveraged during development, not as predictive engines, but as knowledge assistants. Their broad access to global knowledge was applied to schema design, service boundary discovery, functional requirement translation, and code/API generation. This highlights the complementary role of LLMs: they accelerate system design and prototyping, while AMOS ensures resilience, transparency, and adaptability in deployment.

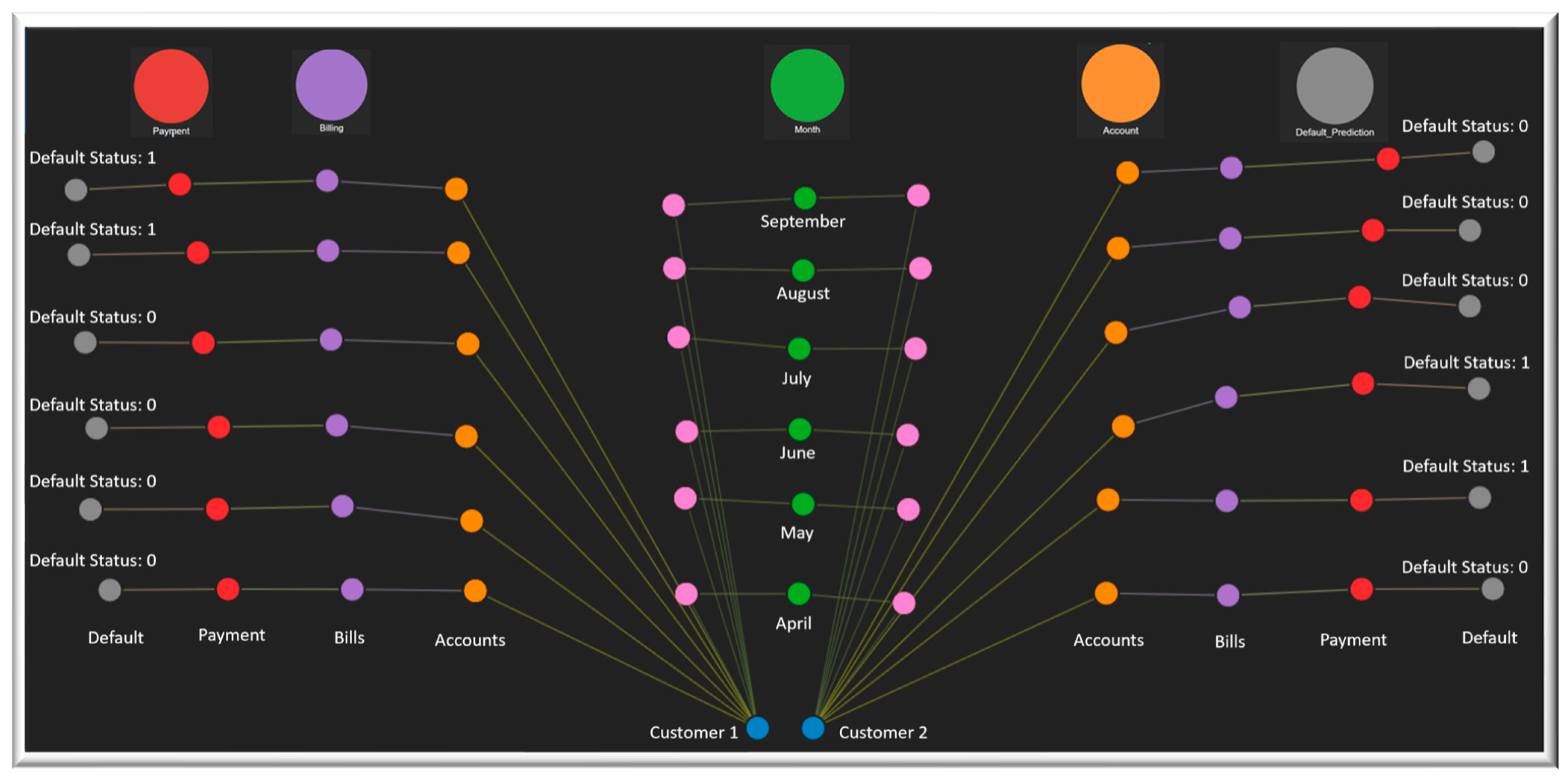

Figure 5 depicts the state evolution of two customers with default prediction status shown. The graph database allows queries to find explanations of the causal dependencies.

4.1. Comparison with Conventional Pipelines

Unlike traditional machine learning pipelines, which treat credit-default prediction as a static process (data preprocessing → feature engineering → model training → evaluation), the AMOS implementation transforms the task into a living, knowledge-centric system. Conventional pipelines deliver one-shot predictions on fixed datasets, with limited adaptability, traceability, or resilience. In contrast, AMOS maintains event-sourced memory, autopoietic feedback loops, and explainable decision trails, enabling the system to adapt to changing behaviors in real time while preserving transparency. This shift marks the difference between data-driven computation and knowledge-driven orchestration, demonstrating the potential of Mindful Machines to extend beyond conventional AI workflows.

Table 1 shows the comparison between two methods.

4.2. Hybrid Prediction Strategy and Method Switching

Beyond contrasting Mindful Machine analytics with conventional pipelines, the implementation also revealed the value of treating different prediction methods as complementary rather than competing. In the textbook setting, the logistic regression model is the primary artifact: it consumes preprocessed PAY_1–PAY_6 features and outputs a probability of default. In the AMOS implementation, this model becomes one component within a broader Default Prediction Service that also hosts a rule-based, month-to-month simulation engine. The two methods offer distinct strengths: logistic regression provides a calibrated, portfolio-level statistical view, while the simulation engine encodes explicit, causal rules for individual account evolution. In practice, this leads naturally to a hybrid strategy. As detailed in

Section 5, we use the simulation engine to transform raw repayment codes into higher-level behavioral indicators (e.g., “ever overdue”, “recent recovery”, “months since last full payment”) and then feed these features into the logistic regression model. This combination yields predictions that retain the statistical sensitivity of machine learning while benefiting from the interpretability and domain structure of rule-based state transitions. Rather than replacing machine learning, the Mindful Machine reframes it as one of several tools governed by explicit knowledge and policies.

Crucially, the AMOS architecture allows the system to select or switch among these methods under changing conditions. The Autopoietic Process Manager (APM), Cognitive Network Manager (CNM), and Software Workflow Manager (SWM) can route specific customer segments or scenarios through different model variants based on policy rules or drift signals monitored by Cognizing Oracles. For example, when repayment distributions shift for a particular cohort, the system can temporarily prioritize the more conservative rule-based engine, fall back to a previously validated model, or deploy a retrained logistic regression variant—without redesigning the application or interrupting service. This hybrid, switchable configuration illustrates how Mindful Machines transform a static prediction pipeline into a governed decision ecosystem, where multiple methods are orchestrated in real time to preserve accuracy, transparency, and resilience.

5. Discussion and Comparison with Current State of Practice

The implementation of AMOS highlights a fundamental departure from conventional machine learning pipelines. In Data Science Projects with Python [

30], the credit-default prediction problem is solved through a linear process of data preprocessing, feature engineering, model training, and evaluation. While effective for static datasets, this approach exhibits several limitations: Lack of adaptability—the model must be retrained when data distributions shift. Bias and brittleness—results are constrained by dataset composition, often underrepresenting rare but critical cases. Limited explainability—outputs are tied to abstract model weights rather than transparent causal chains. Fragile resilience—pipelines are vulnerable to disruptions in data flow or system execution.

In contrast, the AMOS-based implementation demonstrates how a knowledge-centric architecture overcomes these shortcomings. By encoding both functional and non-functional requirements in the Digital Genome, the system embeds resilience and compliance directly into its design.

Technical Realization of Improvements: The claims of enhanced resilience, explainability, and adaptation are achieved through the tight coupling of the DG, Memory Layer, and Autopoietic Layer managers:

Resilience (Self-Healing and Scaling): The Autopoietic Process Manager (APM) and Cognitive Network Manager (CNM) continuously monitor the distributed services and the network topology. Resilience is achieved through automated fault detection, followed by policy-driven actions such as service restarts or elastic scaling based on demand, which includes configuration of network paths for auto-failover using RTO/RPOs defined in the DG.

Figure 6 shows two clusters providing active–active high-availability configuration.

Explainability and Transparency (Auditable Decisions): The event-sourced architecture, anchored by the Cognitive Event Manager, ensures every transaction and system decision is recorded in the Episodic Memory (a persistent graph database). This preserves the causal chain from input event to final prediction, making every outcome auditable via provenance queries. Furthermore, the use of transparent, rule-based reasoning in the prediction service, enforced by the Cognizing Oracles, allows the system to generate human-readable, textual justifications for risk classification, moving beyond opaque model weights.

Real-Time Adaptation: Adaptability is achieved not by offline retraining, but by the SWM and CNM dynamically rewiring and reconfiguring the service network based on real-time policy evaluation. This allows the system to react instantly to detected anomalies (e.g., distributional drift) by switching prediction models or adjusting workflows without requiring a full system-wide deployment cycle.

Autopoietic managers ensure continuity under failure or load changes, while semantic and episodic memory provide persistent context for explainability and adaptation. Cognizing oracles introduce transparency and governance, ensuring that system behavior remains aligned with global goals.

We also compared our results with traditional ML analysis with Logistic regression discussed in the textbook.

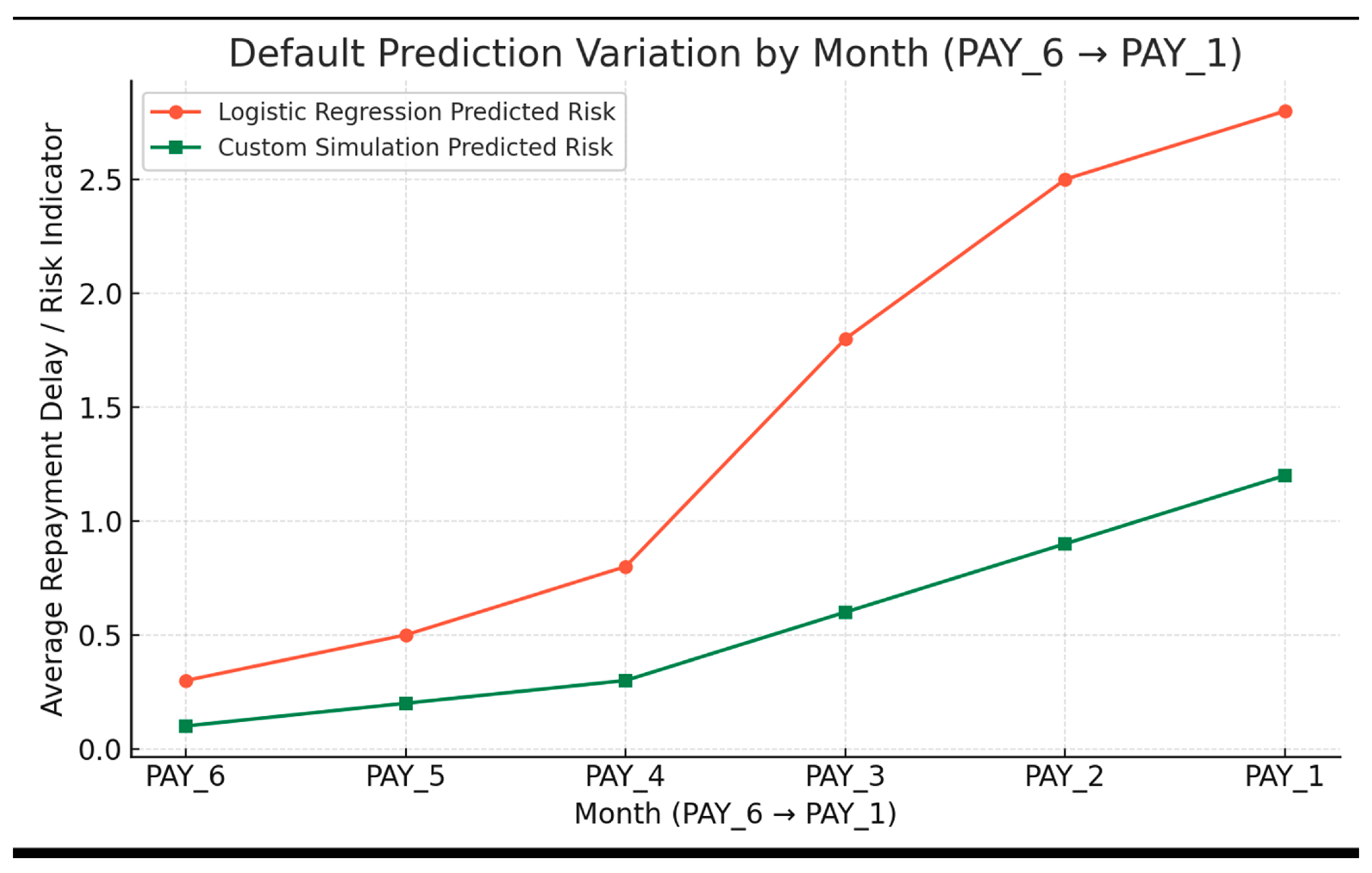

Figure 7 compares predicted repayment delay for selected customers, where PAY_6 corresponds to April and PAY_1 to September. The two methods show a clear behavioral difference:

The Logistic Regression model tends to over-predict defaults around borderline risk scores.

The month-to-month rule engine smooths transient fluctuations by emphasizing recent recovery and consistent behavior.

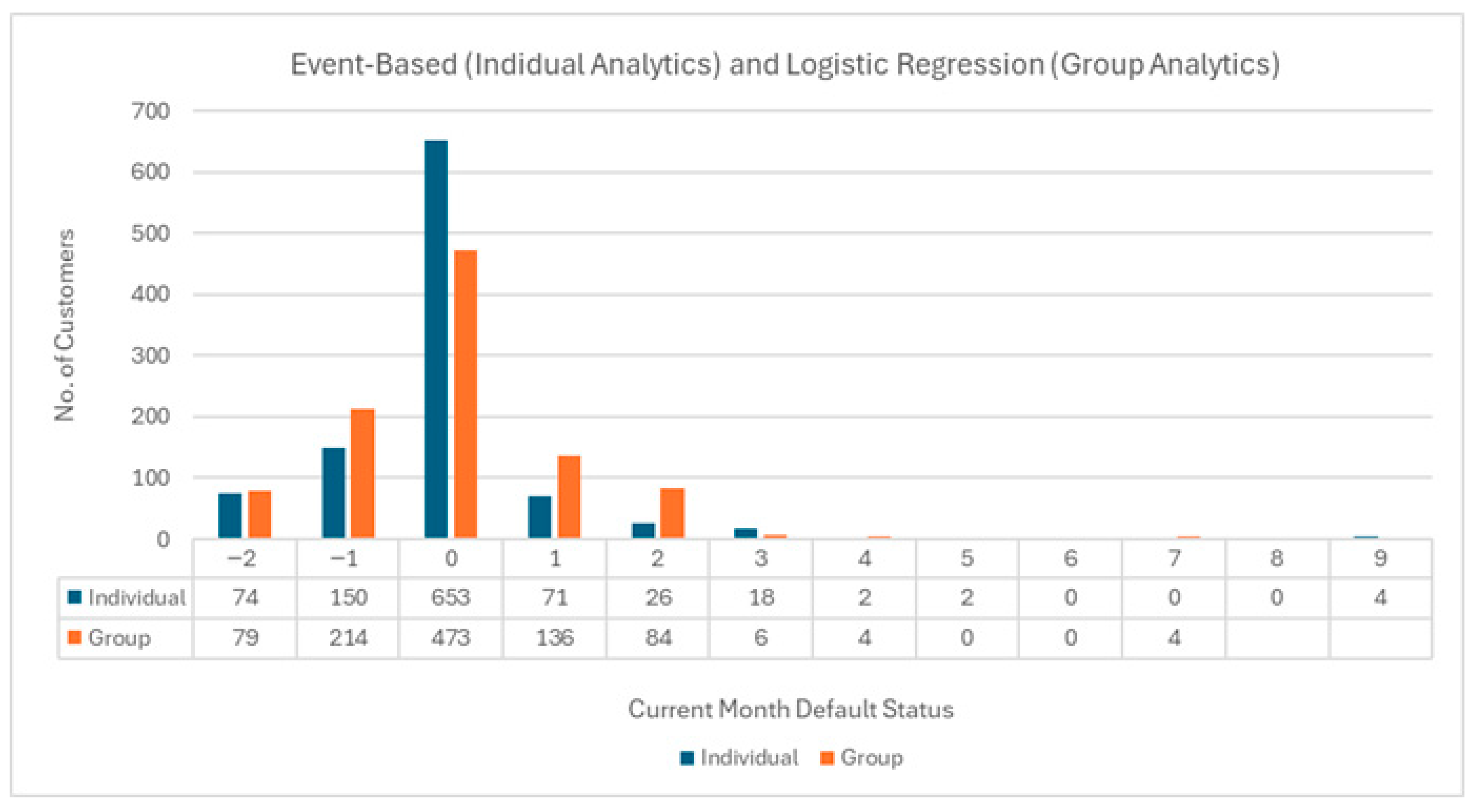

Figure 8 shows the resulting current status in September for the same accounts. From these experiments, several insights emerge:

The rule-based simulation “thinks in causality”:

It models account evolution over time, providing clearer explanations for individual trajectories.

Disagreement cases typically involve customers recovering from past delinquencies:

the statistical model continues to penalize historical behavior, while the month-to-month rules give more weight to recent improvement.

Logistic Regression generalizes historical averages, whereas the month-to-month Mindful Machine personalizes risk based on current, dynamic repayment behavior.

Based on this experience, we do not recommend choosing one method over the other. Instead, we propose a combined strategy:

Use the simulation engine to transform raw PAY_1–PAY_6 codes into higher-level behavioral indicators (e.g., “ever overdue,” “recent recovery,” “months since last full payment”), and then feed these features into a Logistic Regression model.

This yields a model that is both predictive and explainable.

Here are some insights:

The logistic regression model “thinks in probabilities”—it is a snapshot predictor optimized for accuracy over a population.

The rule-based simulation “thinks in causality”—it models account evolution, providing better interpretability for individual trajectories.

Disagreement cases often reflect customers recovering from past delinquencies—where machine learning still penalizes them for their history.

The logistic model generalizes historical averages, while your month-to-month model personalizes outcomes based on dynamic repayment behavior.

We conclude from our experience to use both methods. Use the simulation engine to transform raw PAY_1–PAY_6 into cleaned behavioral indicators (e.g., “ever overdue,” “recent recovery,” “months since full payment”). Feed those into the logistic regression, yielding a model that is both predictive and explainable.

Beyond the loan default case, these findings generalize to a wide range of domains where AI must operate in dynamic, high-stakes environments such as finance, healthcare, cybersecurity, and supply chain management. Traditional pipelines, optimized for accuracy on static datasets, fall short in such contexts. Mindful Machines, by contrast, transform computation into a living process, where meaning, memory, and adaptation are intrinsic to the architecture.

Table 1 summarizes the differences between conventional ML approaches and AMOS. As the comparison indicates, the novelty lies not in replacing machine learning, but in integrating it into a broader autopoietic and meta-cognitive framework that ensures transparency, resilience, and sustainability.

Two patterns stand out:

Tail behavior and risk amplification

The Logistic Regression model assigns almost twice as many accounts to “two or more months delayed” (9.8% vs. 5.2%).

It also roughly doubles the share with a one-month delay (13.6% vs. 7.1%).

In other words, for the same 1000 customers, the statistical model pushes more accounts into high-risk buckets, reflecting its threshold probability view of risk.

Event resolution and monitoring posture

The Mindful Machine places a larger fraction of accounts in the moderate-risk, revolving (PAY = 0) state (65.3% vs. 47.3%), preserving a fine-grained ladder of risk states that can be tracked day-to-day.

This supports continuous, event-driven monitoring: the same customer can be followed as they move from “revolving but compliant” to “delayed one month” to “default_next_month” with explicit, explainable transitions.

Implications

From these results, we draw the following operational conclusions:

Viewed together, the two approaches are not competitors but complements: Logistic Regression provides a statistical, portfolio-level lens, while the Mindful Machine offers an event-centric, knowledge-driven lens that can manage individual trajectories and support richer, graph-based risk reasoning.