1. Introduction

The internet of things (IoT) has gained enormous interest in both scientific and industrial communities, with applications ranging from smart cities to agriculture [

1,

2,

3]. In such systems, wireless communication is a key feature, and technologies such as Wireless Fidelity (Wi-Fi), Bluetooth, and Zigbee protocol (Zigbee) are widely employed [

4]. Most deployments rely on numerous embedded systems integrating Microcontroller Unit (MCU) and sensors, which are typically low-power and often run bare-metal firmware to minimize energy consumption; while manual firmware updates are possible, they require user assistance and do not scale to large deployments [

5,

6,

7]. To overcome these limitations, over-the-air (OTA) update protocols have been developed as a practical and scalable solution.

Real-world IoT installations are often deployed in demanding environments where measurement reliability and long-term maintenance are critical. Similar constraints were observed in airflow-monitoring systems for road tunnels, where stable sensing and remote management significantly impacted overall system performance [

8].

In industrial settings, where thousands of devices may already be deployed, OTA strategies must deliver new configurations and firmware efficiently while minimizing disruption [

5]. OTA updates are also well established in complex systems such as vehicles, where security enhancements have been introduced through decentralized identifiers and distributed ledger technology [

9]. Lightweight and secure OTA mechanisms designed for constrained IoT devices have further demonstrated the importance of combining encryption, compression, and multichannel transmission to reduce latency, memory usage, and energy consumption while resisting man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks [

10]. These examples demonstrate that OTA solutions must address both performance and security challenges.

In remote deployments, stable short-range connections are often unavailable. Technologies such as Global System for Mobile communications (GSM) and Narrowband Internet of Things (NB-IoT) provide long-range connectivity but are limited by energy consumption, making Long Range (LoRa) a preferred option for low-power devices. A hybrid broadcast–unicast strategy was proposed in [

11] to accelerate LoRa OTA in industrial scenarios, while a runtime update mechanism for LoRaWAN Class A devices was shown in [

12] to reduce downtime to milliseconds and minimize transmitted data by more than 99%. For NB-IoT, a proof-of-concept OTA framework demonstrated that large updates can be delivered with less than 0.75% battery overhead [

13]. Together, these works highlight how OTA can be optimized for both long-range reliability and energy efficiency.

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) represent another important domain of the IoT, with applications ranging from environmental monitoring to smart metering. A WSN designed for smart power metering is described in [

14], emphasizing the need for reliable OTA updates to ensure long-term stability. Energy efficiency is equally critical, since WSN nodes are battery-powered or energy-harvesting. An event-driven framework for minimizing operational costs was introduced in [

15], while an Open Voltage Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) algorithm for power management was evaluated in [

16,

17]. Complementary approaches balancing energy and security overhead appear in [

18], and hybrid clustering and routing techniques for extending network lifetime are presented in [

19]. These studies reinforce that OTA update systems must integrate both energy-aware and security-aware design principles for sustainability in large-scale deployments.

Finally, OTA can be implemented using three typical architectures [

5,

20]:

Edge-to-cloud OTA updates: The microcontroller on the edge device is connected to the internet and directly receives firmware from the cloud.

Gateway-to-cloud OTA updates: An internet-connected gateway manages local edge devices and distributes firmware obtained from the cloud.

Edge-to-gateway-to-cloud OTA updates: The gateway downloads the firmware and subsequently transmits it to edge devices, combining aspects of the previous two approaches.

Several OTA frameworks have been proposed in recent years, including Zigbee2MQTT, Mender.io, and BalenaCloud; while these platforms offer valuable insights, they remain limited to either specific communication protocols or high-level operating systems, making them unsuitable for resource-constrained microcontrollers such as the ESP32. Native OTA libraries often lack multi-protocol coordination or version-aware logic. Other studies have explored LoRa and NB-IoT OTA mechanisms with improved energy efficiency [

11,

13], and blockchain-assisted OTA frameworks for secure automotive systems [

9]. Despite these advancements, there remains a lack of unified, lightweight OTA architectures that integrate multiple transport layers and enable centralized version control for microcontroller-based IoT deployments.

The main novelty of this work lies in the design of a unified and automated OTA update architecture for ESP32-based IoT systems that supports multiple communication interfaces (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), Zigbee, LoRa, and GSM) under a centralized versioning and routing framework. Unlike existing single-protocol OTA implementations, the proposed system employs a server-driven architecture that dynamically manages firmware distribution, enabling both production and development branches, compatibility checks, and seamless CI/CD integration for continuous firmware delivery. This approach enhances scalability, maintainability, and security across heterogeneous IoT networks.

2. Related Work

Over-the-air (OTA) firmware updating for IoT and cyber-physical systems has been extensively investigated in recent years. For ESP32-class microcontrollers, vendor documentation and example projects provide Wi-Fi based OTA mechanisms and corresponding API abstractions [

21,

22,

23], as well as reference implementations for BLE- and Zigbee-based updates [

24,

25]. A more general cloud-assisted OTA management architecture for IoT devices using RESTful web services is presented in [

5]. Several works address OTA mechanisms in specific communication technologies and deployment scenarios, including connected vehicles [

9,

26], LoRa- and LoRaWAN-based systems [

11,

12], NB-IoT devices [

13], and ESP32-based nodes in heterogeneous IoT environments [

6,

20,

27,

28]. Survey- and system-level perspectives on secure configuration and remote maintenance pipelines are discussed in [

2,

29].

Security and dependability aspects of OTA updates form a separate but closely related line of research. Several studies propose security frameworks for wireless sensor networks and IoT infrastructures, often combining cryptographic mechanisms with energy-aware routing or clustering [

18,

19]. Lightweight and secure firmware update mechanisms tailored to constrained IoT devices are analyzed in [

10,

11,

12,

13], while broader threat-assessment and testing methodologies for automotive and vehicular OTA systems are presented in [

3,

7,

26,

30]. Access-control and trust-management requirements for large-scale IoT deployments are surveyed in [

31], and open-standard based secure update channels are evaluated in [

32]. ESP32-specific vulnerabilities, including weaknesses in bootloaders and OTA paths, are documented in [

33,

34], further underscoring the need for hardened update mechanisms and end-to-end protection.

Beyond OTA-centric work, there exists a substantial body of literature on wireless sensor networks (WSNs), energy management, and radio propagation, which directly constrains the design of reliable update mechanisms. Studies on smart power metering and shared-resource monitoring using WSNs highlight the importance of low-energy communication, distributed sensing, and robust data aggregation in real deployments [

14,

35]. Event-driven programming approaches and power-management algorithms for sensor nodes demonstrate that minimizing active-time windows and tightly coupling control logic with energy harvesting can significantly reduce operational energy costs [

15,

16,

19]. Complementary work on LPWAN and low-power wide-area technologies analyzes the trade-offs between coverage, energy consumption, and throughput in Sigfox, LoRaWAN, and NB-IoT networks [

4,

13], which are increasingly used as backends for OTA-capable devices.

Radio-frequency propagation characteristics have also been investigated in detail. Experimental measurements of 2.4 GHz ISM-band indoor propagation reported in [

36] show strong multipath fading, path-loss exponents significantly deviating from free-space models, and frequent signal degradation on the order of several decibels. Application-oriented WSN deployments for environmental and structural monitoring, such as water-level estimation and CO

2 concentration tracking in closed spaces [

1,

37], further illustrate practical constraints including multi-hop topologies, periodic wake-up schedules, packet encapsulation overhead, and error handling under non-ideal channel conditions.

Compared with existing work, the architecture proposed in this paper targets a unified OTA framework for ESP32-based devices that integrates multiple communication backends (Wi-Fi, BLE, Zigbee, and LPWAN technologies) while providing centralized version control, release-branch management, and protocol-independent routing on the server side. At the same time, it explicitly incorporates insights from prior research on energy-efficient WSN operation and realistic RF propagation, with the aim of delivering a deployment-ready OTA solution that remains robust under constrained energy budgets, unstable link quality, and heterogeneous network infrastructures.

3. Over the Air Update

OTA update is a mechanism for remotely deploying and installing firmware updates on connected devices, eliminating the need for physical access. This approach is essential for maintaining, enhancing, and securing IoT devices deployed in various environments, often challenging to reach. This paper presents an overview of the OTA updating process, with a particular focus on the implementation for Espressif microcontrollers [

21]. Broader surveys of OTA programming techniques, such as the work by Arakadakis et al. [

38], highlight the fragmentation of existing IoT update solutions and motivate unified architectures capable of supporting multiple communication protocols [

38].

The OTA update process involves several key steps. First, a new version of the firmware must be prepared by the manufacturer or developer. This firmware may include feature enhancements, bug fixes, or security patches. The new firmware is then uploaded to an update server, which can be configured to be accessible via various communication protocols such as HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP), HyperText Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS), or File Transfer Protocol (FTP) [

22,

28,

30].

Connected devices periodically check for the availability of updates by querying the server. This check can be scheduled at regular intervals or triggered by specific events. When an update is detected, the device downloads the firmware from the server. To ensure the firmware’s integrity, the device performs validation checks using hash functions or digital signatures [

21].

Following successful validation, the firmware is installed into the device’s flash memory. This process must be carefully managed to prevent data corruption. After installation, the device restarts to activate the new firmware, and post-installation tests are conducted to verify that the update has been applied correctly and that the new firmware operates as expected.

The partition table is a data structure that defines how the Espressif 32-bit System on Chip (ESP32)’s flash memory is divided into partitions, each serving a specific purpose, such as storing the bootloader, application code, OTA data, or other essential information. Typically located at the beginning of the flash memory, the partition table acts as a map for the device’s memory layout, playing a crucial role during the boot process and in memory allocation throughout the device’s operation. Common partition types include the bootloader, application partitions, OTA data, Non-Volatile Storage (NVS), and file system partitions.

Different types of partition tables are supported by the ESP32, including the Single App Partition Table, which is simple with a single application partition and no OTA support, the OTA Partition Table that allows for multiple application partitions to support OTA updates, and Custom Partition Tables, where developers can define specific configurations to meet unique application needs. The bootloader reads the partition table during the boot process, determining which partitions to use for booting and running applications. During OTA updates, new firmware is written to an inactive application partition, with the OTA data partition updated to point to the new firmware after successful verification. This setup allows the device to switch between firmware versions safely, providing a fallback mechanism in case of update failures [

21].

For Espressif devices, such as the ESP32, the OTA update process is facilitated through the Espressif library, which provides specific Application Programming Interface (API) for managing OTA updates. For example, on the ESP32, the HTTPUpdate API allows for OTA updates via HTTP/HTTPS, streamlining the update process. The library also supports other communication protocols, including BLE and Zigbee, although Wi-Fi remains the most common due to its speed and ease of use. Additionally, the Espressif library includes functionality for managing rollbacks, allowing the device to revert to a previously valid firmware image if the new update is found to be defective. This rollback feature ensures that the device remains operational even if an OTA update fails, enhancing the reliability of the update process [

21,

39]. The importance of reliability, bandwidth efficiency, and strict version management in OTA workflows is also emphasized in broader IoT analyses such as Bauwens et al. [

40], which further motivates the design of robust multi-protocol update mechanisms [

40].

3.1. Security of OTA Updates and Communication

Secure firmware delivery is a critical requirement in any OTA-capable IoT system, as corrupted or spoofed updates may lead to device takeover, large-scale botnet formation, or permanent denial of service. Several surveys highlight that insufficient authentication and weak communication protection remain the most common vulnerabilities in real-world OTA deployments [

30,

41].

In the proposed framework, security is addressed at three levels - securing communication channels, integrity and authenticity validation and secure boot or rollback protection.

3.2. Secure Communication Channels

All firmware transfers are performed over encrypted channels using HTTPS/TLS. This prevents eavesdropping and man-in-the-middle modification of firmware images, following recommendations for secure IoT update delivery [

10,

32]. Devices authenticate using per-device credentials (API tokens or client certificates), ensuring that only registered nodes may request or download updates [

26].

3.3. Integrity and Authenticity Validation

Each firmware image is hashed and digitally signed during the build process using asymmetric cryptography (e.g., Ed25519). The bootloader contains the corresponding public key and verifies both the signature and the hash before activating a new image. Similar techniques have been widely adopted in vehicular OTA and safety-critical IoT systems [

9,

26].

3.4. Secure Boot and Rollback Protection

ESP32 devices rely on a dual-partition OTA layout. New firmware is written to an inactive slot and validated before being marked active. If the system fails to boot repeatedly, the bootloader automatically rolls back to the last known good firmware. This improves resilience and reduces the risk of bricking devices in large distributed deployments [

18,

30].

Together, these mechanisms enforce secure update distribution and mitigate typical IoT OTA attack vectors such as spoofed update servers, tampered firmware images, or downgrade attacks.

3.5. OTA Update via Wi-Fi

The updated firmware is uploaded to a server accessible via Wi-Fi, which handles HTTP or HTTPS requests, making it straightforward for devices to fetch the firmware [

23].

Devices equipped with Wi-Fi connectivity periodically connect to the update server to check for new firmware availability. This connection allows them to check for the availability of new firmware. The frequency of these checks can be set based on the device’s requirements or operational schedule. When a device detects that a new firmware version is available, it sends a request to the server to download the update. This request typically involves querying the server for the latest version of the firmware and obtaining the firmware file [

22].

The device downloads the firmware file from the server over the Wi-Fi connection. Given the high-speed capabilities of Wi-Fi, this process is generally rapid, allowing for quick transfers even for large firmware files. After downloading the firmware, the device performs a verification process to ensure that the firmware is intact and has not been corrupted. Once verified, the firmware is installed into the device’s flash memory.

After the installation is complete, the device reboots to apply the new firmware. This step activates the updated software. Following the reboot, the device may perform additional checks to confirm that the firmware update was successful and that the device is functioning correctly with the new software.

Wi-Fi provides a high-speed connection, making it efficient for transferring large firmware files quickly. This rapid update process minimizes downtime and ensures that devices are swiftly updated with the latest firmware. Nevertheless, measurements from real-world deployments show that OTA performance can degrade significantly under unstable wireless conditions or outdoor scenarios [

42], which underlines the need for resilience mechanisms in Wi-Fi-based OTA implementations. Implementing OTA updates via Wi-Fi is relatively straightforward. Wi-Fi is a common communication protocol, and many devices are already equipped with Wi-Fi capabilities. Wi-Fi is one of the most commonly used methods for OTA updates due to its widespread availability and the high-speed data transfer it supports. It is well-suited for scenarios where devices are connected to a stable and robust network infrastructure [

42].

One drawback of using Wi-Fi for OTA updates is its relatively high power consumption. Wi-Fi connectivity can be energy-intensive, which may be a concern for battery-operated devices. The power requirements for maintaining a Wi-Fi connection and transferring data can impact the device’s battery life. Devices equipped with Wi-Fi typically query the update server at regular intervals to check for new firmware updates. This polling mechanism ensures that devices stay current with the latest software, although it may involve some overhead in terms of network traffic and server load.

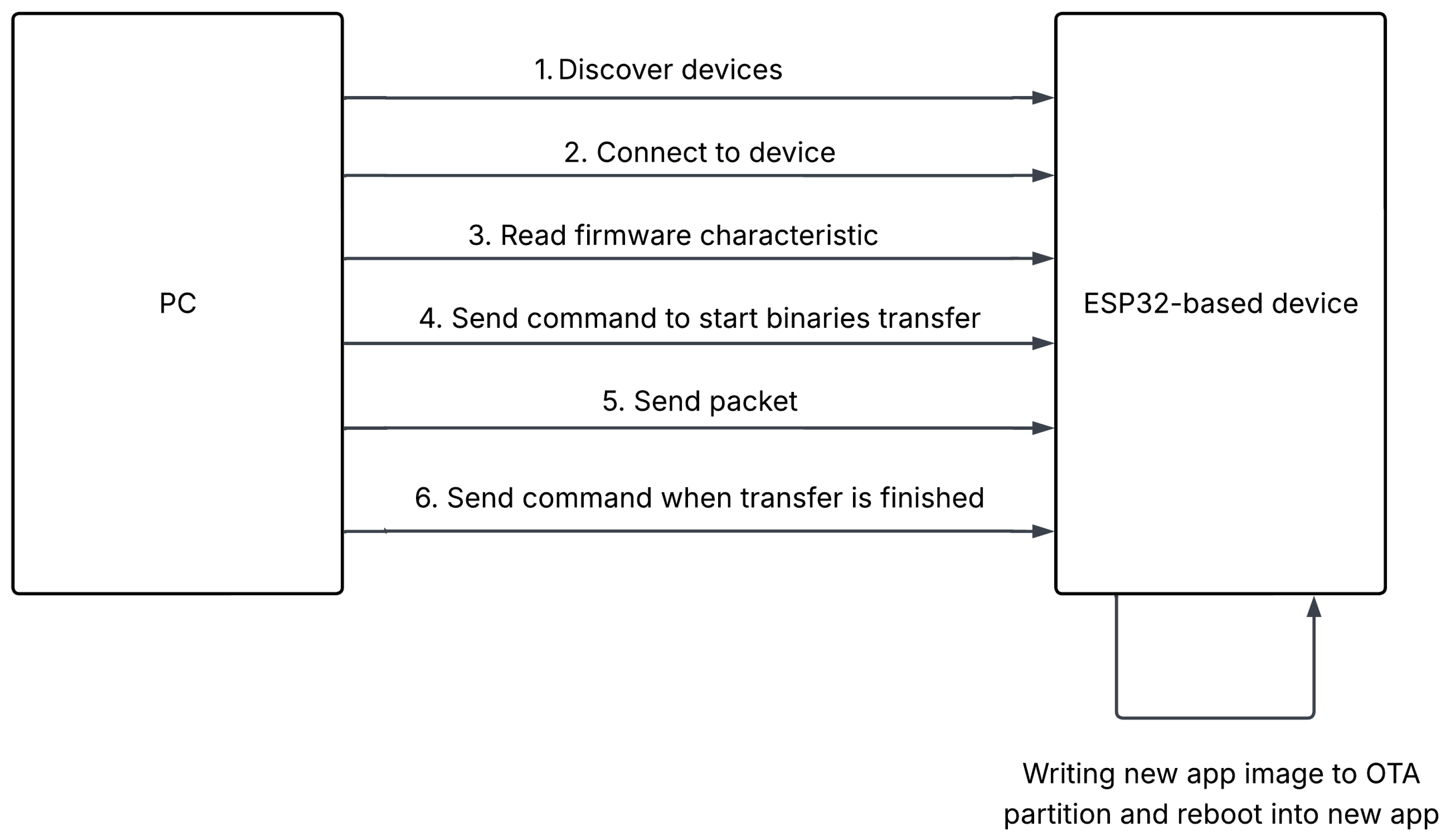

Design and diagram of updating is consequently shown on

Figure 1.

3.6. OTA Update via Bluetooth Low Energy

The new firmware is uploaded to a central server that will be accessed by the client (typically a smartphone or a gateway) to initiate the update process [

22].

The BLE client searches for nearby devices that need a firmware update. Once the target devices are discovered, the client initiates a connection to each device. In this setup, the client acts as the central server, and the devices (which need the update) act as peripheral servers. Upon establishing a connection, the client sends a request to the device to start the update process. The client then begins to transfer the firmware to the device in small packets. BLE is designed to be energy-efficient, which means that even though the transfer speed is slower compared to Wi-Fi, it consumes significantly less power, making it suitable for battery-operated devices [

24].

As the device receives the firmware packets, it performs checks to ensure the integrity and completeness of the data. This is typically done using hash functions or digital signatures to verify that the firmware has not been corrupted during the transfer. Once the device has received the entire firmware and verified its integrity, it proceeds to install the firmware into its flash memory. After installing the firmware, the device reboots to activate the new software. Post-reboot, the device performs additional checks to ensure that the firmware update was successful and that the device is functioning correctly with the new firmware [

24]. From a security perspective, El Jaouhari and Bouvet [

41] discuss typical IoT OTA attack vectors, including spoofed update sources and insufficient authentication, reinforcing the necessity of integrity checks and authenticated BLE update channels [

41].

BLE provides a relatively quick transfer rate for small to medium-sized firmware files, making the update process efficient, and while it is not as fast as Wi-Fi, the speed is sufficient for most IoT applications. One of the primary advantages of BLE is its low power consumption. BLE is specifically designed to be energy-efficient, which makes it ideal for devices that rely on battery power. As a Bluetooth technology, BLE benefits from widespread compatibility and support across many devices, including smartphones and gateways. This broad compatibility makes it a versatile option for OTA updates. In the BLE OTA update process, the client (the central server) manages the update process by communicating with the servers (the devices). This client-server model ensures that the update process is controlled and systematic [

24]. Full diagram is shown on

Figure 2.

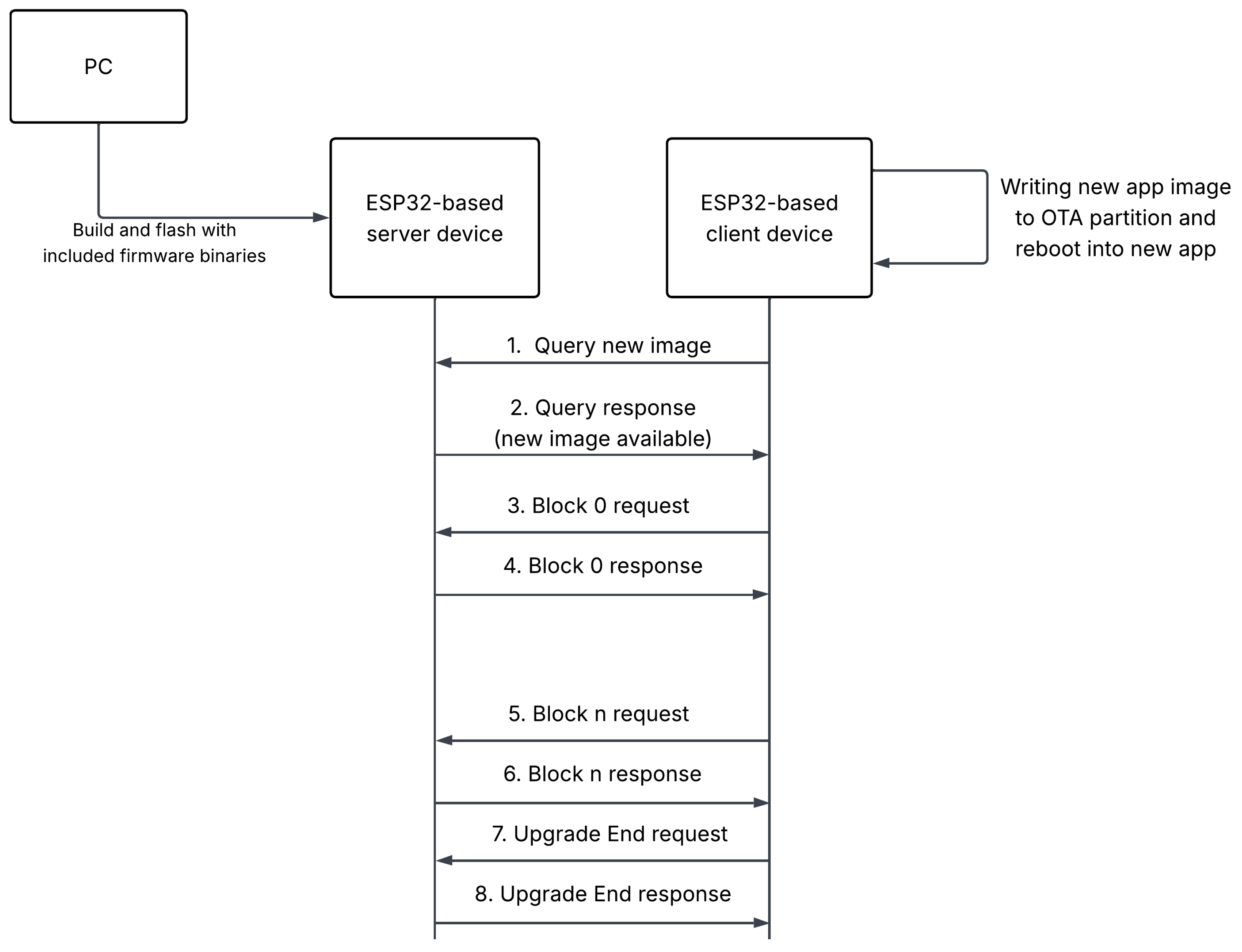

3.7. OTA Update over Zigbee

The firmware is compiled into an image suitable for distribution. Unlike other methods, Zigbee requires a Zigbee coordinator or server device that manages the update process. This server can be an IoT gateway or a specific device within the Zigbee network, where the new firmware image is uploaded [

25].

The Zigbee server identifies and connects to target devices within the Zigbee mesh network that require the firmware update. Zigbee’s mesh network topology allows for robust communication pathways. The server begins transferring the firmware to the target devices. This transfer is extremely slow compared to Wi-Fi or BLE due to Zigbee’s lower data transfer rates. However, the process is highly energy-efficient, ideal for devices running on limited power sources such as batteries [

25]. Ilustration of OTA update over Zigbee is shown on

Figure 3.

Similar challenges related to long update times and strict energy constraints have also been reported in other LPWAN-based OTA technologies, such as LoRaWAN, where FUOTA methods for TinyML workloads must be carefully optimized to minimize energy consumption [

43]. Additional studies demonstrate that modular FUOTA mechanisms for LoRaWAN require further optimization due to severe bandwidth and energy restrictions [

44].

As with other OTA methods, the receiving device performs integrity checks on the incoming firmware packets to ensure data integrity. Once the firmware is fully received and verified, it is installed into the device’s flash memory. After installing the firmware, the device reboots to activate the new software. Post-reboot, the device performs additional checks to confirm that the firmware update was successful and that the device is functioning correctly with the new firmware.

Zigbee’s data transfer rate is significantly slower than Wi-Fi and BLE, making the firmware update process much longer. This can be a limiting factor for large firmware updates but is manageable for smaller updates or infrequent updates. The low power consumption during the OTA update process helps extend the battery life of these devices. Zigbee operates over radio frequencies, providing reliable wireless communication within its network. The mesh network topology enhances connectivity and range by allowing data to hop between multiple devices [

25].

In a Zigbee network, the server responsible for OTA updates is typically installed on a dedicated device, such as a Zigbee coordinator or gateway. This device manages the update process and distributes the firmware to target devices. The new firmware image must be built and uploaded to the Zigbee server, which then manages the distribution and installation of the firmware to the devices within the network. It is possible to configure a Zigbee server on a PC using appropriate Zigbee dongles and software. This setup can provide a flexible and powerful solution for managing OTA updates within a Zigbee network [

25]. Scalable multi-hop firmware dissemination is an active research topic across IEEE 802.15.4 [

45] technologies, with recent DSME-based frameworks demonstrating improved reliability for large industrial IoT deployments [

46].

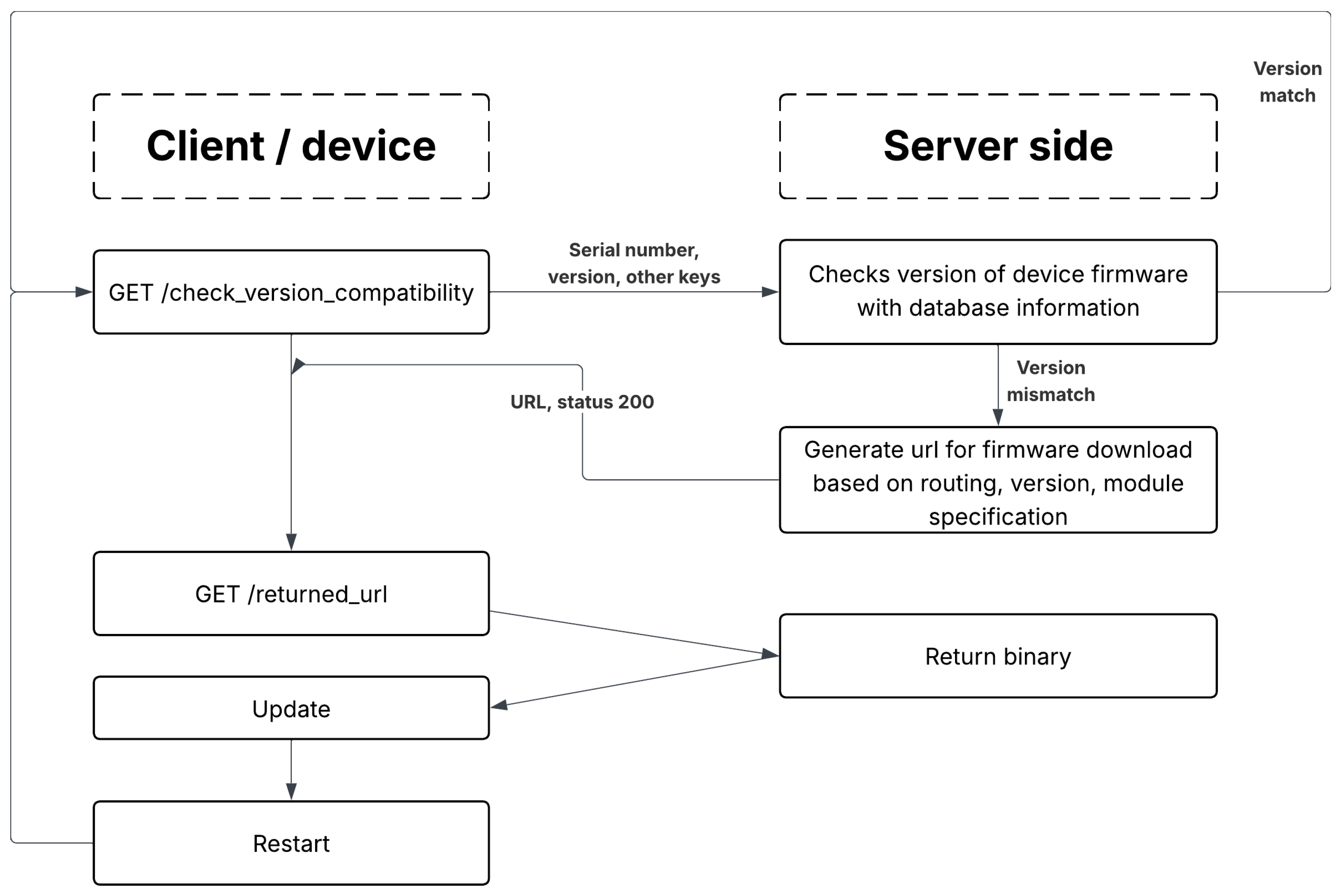

4. Updating Service Architecture

The following section describes the process flow of the Over-the-Air (OTA) firmware update system. The interaction occurs between a client device and a server-side application. Two main paths are possible: a version match, where no update is required, and a version mismatch, where a firmware update must be applied. An example database schema is shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, and the overall workflow is illustrated in

Figure 4.

4.1. Version Match Path

The client sends a GET HTTP request to the endpoint /check_version_compatibility, containing its serial number, firmware version, and any required identification or authentication keys. The server compares the provided firmware version with the one stored in the database. If the versions match, the server responds with status code 201. In this case, no update is required, and the process terminates.

4.2. Version Mismatch Path

The client again sends a GET request to /check_version_compatibility using the same parameters. The server compares the firmware version reported by the device with the current version stored in the database. If a mismatch is detected, the server generates a firmware download URL based on the routing information, target firmware version, and module specification. It responds with status code 200 and includes the generated download link, for example: /module_type/routing/version/firmware.bin.

4.3. Update Download and Installation

The client then sends a request to the returned firmware URL (/returned_url). The server responds by providing the binary firmware file. The device downloads the firmware, verifies its integrity, installs the new version, and restarts to complete the update process.

5. Extended OTA Architectures: BLE, Zigbee, LoRa, GSM

While the baseline OTA system provides a reliable update mechanism over Wi-Fi, more complex network environments require specialized architectures. In particular, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) and Zigbee introduce specific constraints and opportunities that influence the update process. Both approaches are designed with attention to energy efficiency and robustness but require different infrastructure components and dataflow optimization strategies.

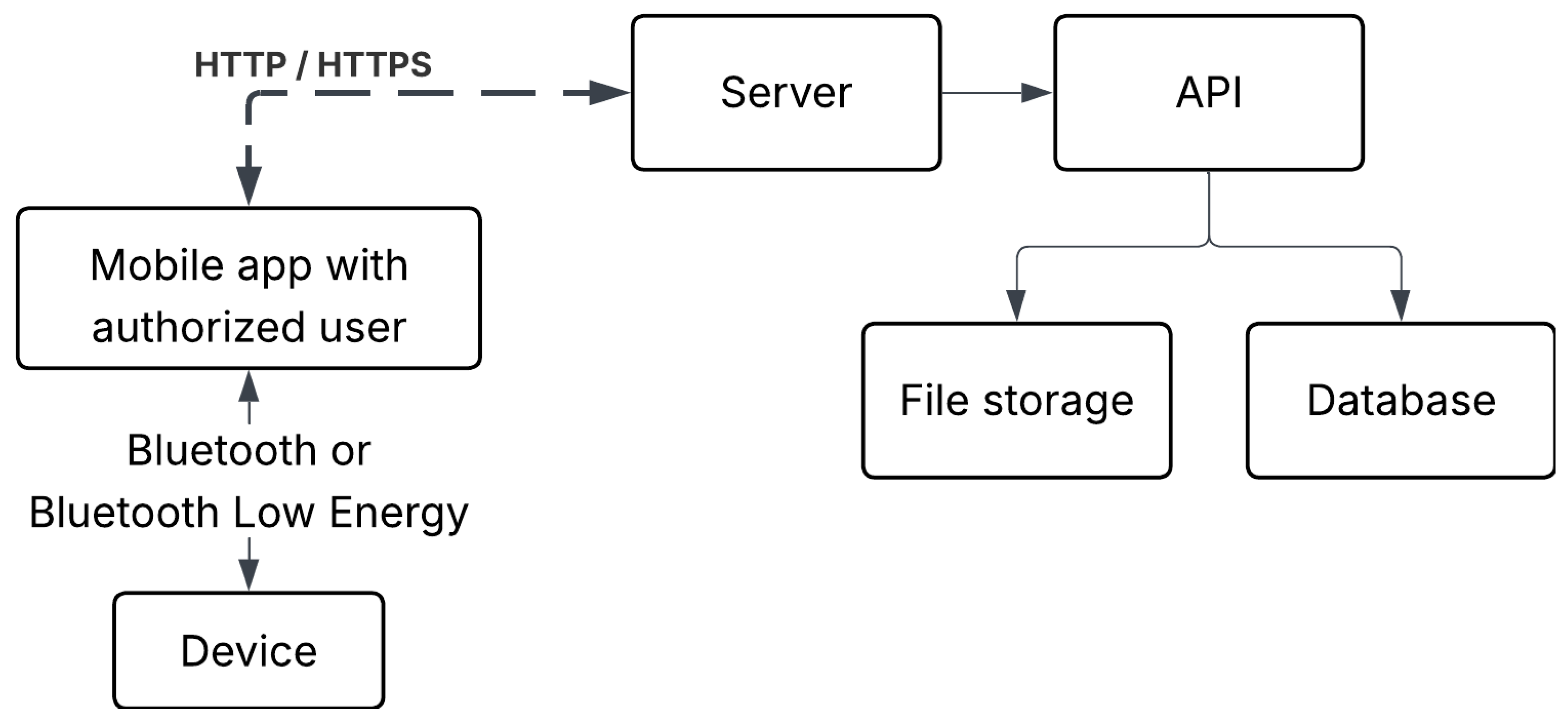

5.1. OTA Updates over BLE with Mobile Application Support

For BLE-based updates, the update process involves a mobile application acting as an intermediary between the update server and the end device. The workflow (

Figure 5) is as follows:

- 1.

The mobile application automatically queries the server with the device’s current firmware version.

- 2.

If a version mismatch is detected, the mobile application downloads the appropriate firmware image into a temporary repository on the mobile device.

- 3.

The firmware is then transferred via BLE to the target device in small, reliable packets, ensuring integrity through checksum verification.

- 4.

Upon successful installation and restart of the device, the temporary firmware file is removed from the mobile repository to save storage and prevent redundancy.

This architecture leverages the widespread availability of smartphones while compensating for BLE’s limited bandwidth. By preloading the firmware into the mobile application before transfer, interruptions in connectivity are minimized and the overall dataflow remains efficient. Dataflow optimization is achieved through packet segmentation, error correction at the BLE layer, and by limiting redundant transfers across multiple devices.

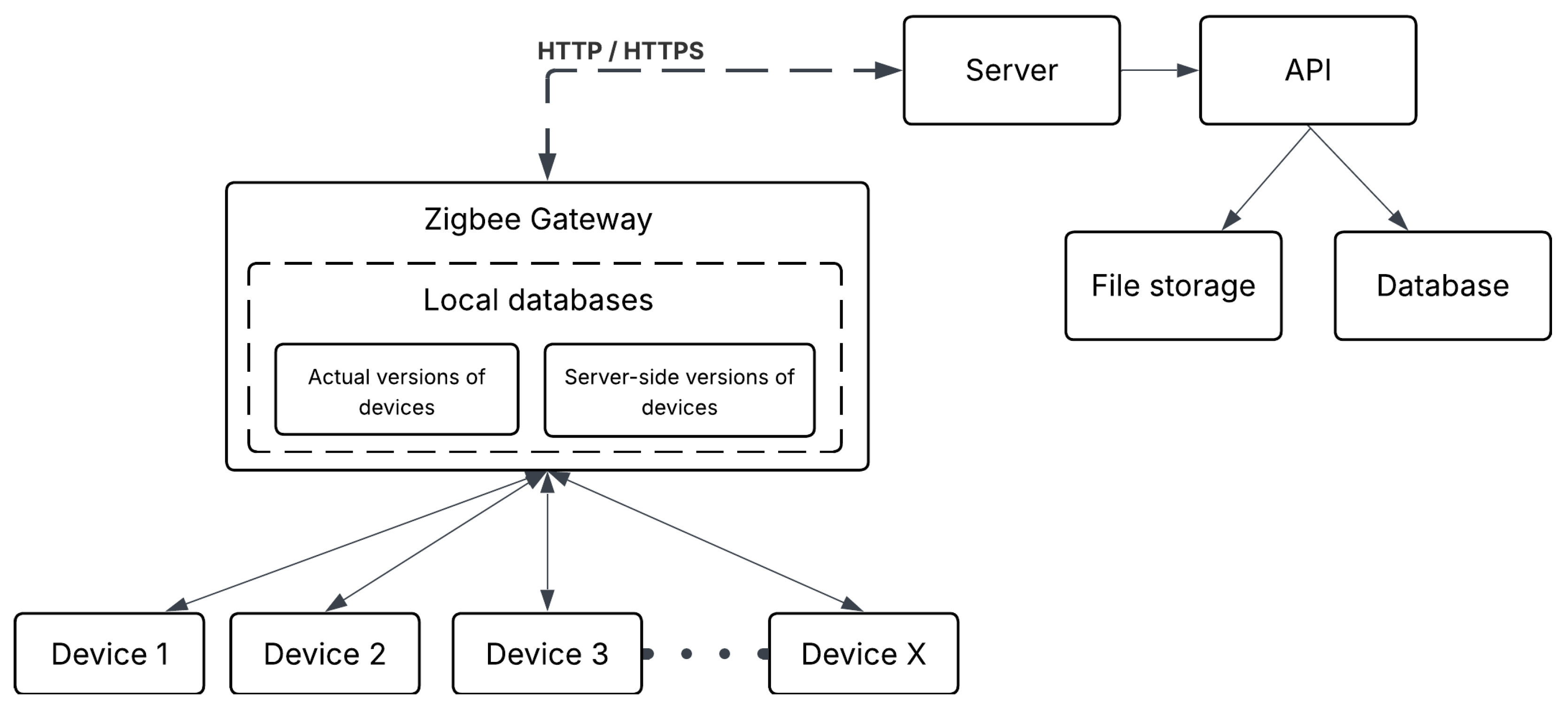

5.2. OTA Updates over Zigbee with Gateway Coordination

For Zigbee-based networks, a gateway device plays a central role in managing OTA updates. The gateway maintains a temporary database containing the firmware versions of all connected devices, along with the latest versions available on the server. The update process (

Figure 6) proceeds as follows:

- 1.

The gateway periodically synchronizes with the server to fetch metadata about available firmware versions.

- 2.

It compares stored device versions against server versions to detect mismatches.

- 3.

When mismatches are found, the gateway distributes updates incrementally, handling one firmware version at a time across the connected Zigbee devices.

- 4.

After each successful device update, the temporary version database is updated to ensure consistency and traceability.

Due to Zigbee’s limited bandwidth, dataflow optimization is critical. This can be achieved through:

Incremental firmware distribution (version by version rather than all at once),

Local caching of firmware binaries at the gateway to avoid repeated server downloads, and

Scheduling updates to minimize network congestion in dense Zigbee meshes.

5.3. Dataflow Optimization Considerations

In both BLE and Zigbee OTA workflows, efficient dataflow management is essential to ensure stability and minimize update latency. BLE optimization focuses on reducing redundant mobile–server transfers, while Zigbee optimization relies on caching, incremental updates, and congestion-aware scheduling. Together, these approaches extend the robustness of OTA updates beyond Wi-Fi, making the system adaptable to a wide variety of IoT environments.

In addition to Wi-Fi, BLE, and Zigbee, new technologies and programming paradigms are expanding the possibilities for OTA updates on embedded devices. Among these, the use of bare-metal Rust for ESP32 development, as well as long-range communication technologies such as LoRa and GSM, represents a promising direction.

The integration of Rust, LoRa, and GSM into OTA workflows demonstrates the adaptability of modern update systems. Bare-metal Rust on ESP32 provides software-level safety and maintainability, while LoRa and GSM extend the reach of OTA updates to remote and mobile devices. Each technology requires tailored dataflow optimizations to account for bandwidth, latency, or cost constraints. Together, these approaches highlight the flexibility and scalability of OTA updates across diverse IoT deployment scenarios.

5.4. OTA Updates over LoRa

LoRa is well-suited for IoT applications requiring long-range communication with low power consumption, but it introduces severe bandwidth constraints. Full OTA updates over LoRa must therefore be optimized for efficiency. The update workflow typically includes:

- 1.

Fragmentation—firmware images are split into small packets compatible with LoRa payload sizes (e.g., 51–222 bytes),

- 2.

Broadcast and unicast combination—broadcast reduces the number of redundant transmissions, while unicast ensures reliability for devices that missed packets, and

- 3.

Forward error correction—optional redundancy bits are added to recover from packet loss without retransmission.

Due to the limited data rate of LoRa, delta updates (transmitting only differences between firmware versions) and compression are often employed. This allows devices deployed in remote areas to receive critical security patches and updates without exhausting their battery resources.

5.5. OTA Updates over GSM

GSM and cellular IoT technologies (e.g., Long Term Evolution for Machines (LTE-M), NB-IoT) offer higher bandwidth compared to LoRa, making them suitable for distributing larger firmware binaries. The OTA update process over GSM involves:

- 1.

The device establishes a mobile data connection to the update server.

- 2.

It checks for the latest firmware version and downloads the binary file directly.

- 3.

To minimize costs, updates can be scheduled during off-peak hours or configured for partial (delta) transfers.

The main challenges of OTA over GSM are data costs, energy consumption during cellular communication, and intermittent coverage in rural areas. Dataflow optimization strategies include caching firmware at local gateways, compressing binaries before transfer, and splitting updates into resumable chunks.

6. Analytical Model of OTA Update Process

To complement the empirical evaluation, a simplified analytical model of the OTA process was developed to quantify the main timing, reliability, and energy parameters. This model provides a theoretical framework for evaluating performance and scalability under various communication conditions.

6.1. Timing Model

The total update duration can be expressed as:

where each component represents the time required for version verification, binary transfer, flash writing, and system reboot, respectively.

The firmware download time is approximated by:

where

S is the firmware size (in bytes) and

B is the average useful throughput (in bytes/s). This expression assumes a steady-state transfer rate without retransmissions. In practical networks, retransmissions due to packet loss slightly increase

according to the expected retry rate

derived below.

6.2. Reliability Model

Transmission reliability is modeled as a Bernoulli process with independent packet losses. If

p denotes the packet loss probability and

m the total number of packets per update, then the probability of successfully completing an update without retransmission is:

The expected number of retransmissions can be approximated by:

As p increases, both the expected latency and the total energy cost of the update grow nonlinearly, which emphasizes the importance of reliable link-layer error correction.

6.3. Energy Consumption Model

The total energy cost of an update is estimated as:

where

and

denote the number of transmitted and received packets, and

represent the average energy per packet transmission and reception, respectively. The processing overhead

includes checksum verification, flash writing, and cryptographic signature validation.

Assuming

J and

J per packet with

the total energy consumption per OTA update is approximately:

This estimate aligns with experimental results measured in

Section 7, confirming that communication overhead dominates the total energy consumption.

In addition to communication and processing costs, cryptographic verification contributes a measurable but minor overhead. On the ESP32 microcontroller, computing a SHA-256 hash over a 1 MB firmware image requires approximately 25 ms and 2.4 mJ of energy, while Ed25519 signature verification takes about 4.8 ms and 3.5 mJ. These operations represent less than 1% of the total update duration and energy but are essential for ensuring firmware authenticity and for protecting against rollback, replay, and man-in-the-middle attacks. The adopted security model follows a Dolev–Yao adversary assumption, where the attacker can eavesdrop, inject, or modify packets within the network but cannot compromise private cryptographic keys.

6.4. Delta Updates and Fragmentation Efficiency

When delta updates are employed, only the difference between firmware versions (

) is transmitted. The relative size reduction ratio is given by:

The total update time then becomes:

where

and

are the compression and decompression times. Forward Error Correction (FEC) introduces redundancy factor

, increasing transmission volume by

and reducing packet loss effects at the cost of additional processing time. The effective throughput under FEC protection is:

These relationships allow estimating the tradeoff between computational overhead and transmission efficiency, which is crucial for optimizing OTA performance in low-bandwidth networks such as LoRa or Zigbee.

6.5. Optimization Considerations

The optimal OTA configuration can be viewed as a constrained optimization problem:

where

a represents the selected communication architecture (Wi-Fi, BLE, Zigbee, LoRa, GSM). This formulation enables the designer to balance latency and energy consumption when choosing the appropriate OTA mechanism for large-scale IoT deployments.

7. System Testing and Results

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed OTA update architecture across the three communication models examined in this work, namely Wi-Fi, Zigbee, and BLE. These models were assessed under identical experimental conditions to enable a systematic comparison of their performance, reliability, and suitability for firmware distribution in heterogeneous IoT environments. The evaluation was conducted within a controlled test environment, where up to twenty devices were simultaneously connected to a public server to assess performance, operational stability, and version-management capabilities. Each device periodically queried the server for update availability, retrieved firmware images when provided, and executed the update process autonomously.

Two versioning tracks were maintained during the evaluation:

Development firmware — used for testing and rapid iteration. These builds were frequently updated and deployed only to selected devices.

Production firmware — intended for stable operation. These versions were rolled out to all devices once the development builds had been validated.

This separation between development and production versions ensured that experimental features could be verified without affecting the stability of devices running in production. Testing confirmed that the server was capable of handling simultaneous update checks and firmware distribution for multiple devices. The architecture maintained consistency in version control, correctly distinguishing between development and production firmware, and reliably serving the appropriate binary images. The overall stability of the system was validated by repeated update cycles across all connected devices without failures or data corruption.

The experimental validation included measurements of average update duration, power consumption, and disconnection rates. For twenty ESP32 devices connected simultaneously, the average update time was approximately 18 s per device over Wi-Fi and 65 s over BLE. The mean power draw during the update process was 0.83 W, corresponding to an average energy cost of 15.1 J per update. No data corruption or firmware installation failures were detected, and only a single transient disconnection (5%) was observed in BLE mode. These metrics confirm the robustness and energy efficiency of the proposed OTA framework under realistic operating conditions.

All tests were conducted under controlled conditions, with the devices located approximately 5 m from the Wi-Fi access point and Bluetooth gateway. The average packet loss rate during transmission was below 1.5%, and the network load remained under 20% throughout the tests. Each experiment was repeated ten times under identical conditions to ensure statistical reliability. The standard deviation of update duration did not exceed 4.2% for Wi-Fi and 6.8% for BLE connections, confirming stable update performance across sessions.

For comparison, Espressif’s native OTA library for the ESP32 platform achieves an average update duration of approximately 22 s over Wi-Fi and lacks multi-version coordination or routing logic. The proposed architecture reduced the update duration by roughly 15% while introducing centralized version control, dynamic routing, and automated branching. Compared to Zigbee2MQTT-based OTA mechanisms, which are limited to single-protocol communication, the presented framework enables unified firmware management across heterogeneous IoT protocols under a common server-driven infrastructure. Further comparison based on update time and protocol support is in

Table 3.

The energy consumption observed in experiments closely aligned with the analytical estimates, confirming that communication energy is the primary cost driver in the overall Over-The-Air (OTA) process. This correlation validates the accuracy of the analytical model and supports the idea that optimizing transmission parameters can lead to significant energy savings. Further comparison of power consumption is in

Table 4.

The proposed system achieves lower update latency compared to existing frameworks while supporting multiple communication protocols and full version management.

Energy and reliability metrics are not reported for competing OTA frameworks; therefore, a direct quantitative comparison is only possible for the proposed system, for which experimental measurements are available.

Scalability and Resilience Analysis

These results clearly demonstrate scalability, as increasing the number of simultaneously connected devices (up to twenty) did not lead to any meaningful increase in update time, packet loss, or server response latency. The system also shows strong resilience: no firmware corruption occurred during repeated update cycles despite packet-loss conditions up to 1.5%, and the use of rollback-capable OTA partitions ensured safe recovery in all scenarios. Integrity validation through SHA-256 hashing and version-matching logic further contributed to reliable operation across both Wi-Fi and BLE updates.

Overall, the results demonstrate that the proposed OTA update solution is scalable, resilient, and suitable for deployment in environments where both testing and stable operation must coexist. The combination of analytical validation, repeatable experiments, and multi-protocol comparison provides a comprehensive proof of concept, supporting the framework’s applicability to diverse IoT ecosystems.

8. Future Work

Future work will focus on extending OTA support for BLE and Zigbee-based ESP32 devices, integrating automated CI/CD pipelines for firmware delivery, and deploying a remote build server to ensure reproducible builds and efficient artifact management. Additional enhancements will include device-side diagnostic mechanisms for evaluating release stability, support for bare-metal Rust firmware to improve memory safety and maintainability, and the incorporation of advanced security features such as mutual authentication, encrypted update channels, digital signature verification, and rollback protection. Together, these improvements aim to strengthen the reliability, scalability, and resilience of OTA processes in large-scale IoT deployments.

9. Conclusions

This work presented the design, implementation, and evaluation of a unified OTA update architecture for ESP32-based IoT devices, addressing the limitations of existing update mechanisms that are often fragmented across protocols and constrained by network reliability. The proposed architecture supports controlled version management, separation of development and production firmware streams, and automated multi-device distribution, thereby removing the operational overhead traditionally associated with manual updates.

Experimental results obtained from deployments involving up to twenty concurrent devices demonstrated that the system is stable, predictable, and scalable under realistic operating conditions. The architecture reliably distinguished between development and production branches, enabling rapid testing of experimental features without jeopardizing system integrity. The evaluation further confirmed that the proposed update workflow can sustain high success rates even when operating across heterogeneous communication mediums.

Beyond Wi-Fi, the extended OTA mechanisms over BLE, Zigbee, LoRa, and GSM proved that multi-protocol delivery is feasible when supported by protocol-aware optimizations such as packet segmentation, incremental transmission, caching strategies, and congestion-aware scheduling. These adaptations are essential for maintaining reliability in bandwidth- and energy-constrained environments, and they broaden the applicability of the architecture to large-scale industrial and remote IoT deployments.

Security considerations were integrated into the update workflow through encrypted communication channels, digital signature verification, and rollback-protected activation. This combination ensures firmware authenticity and resilience against tampering—key requirements highlighted in recent OTA security analyses.

Looking forward, several enhancements are anticipated. The integration of bare-metal Rust into the OTA lifecycle is expected to further increase memory safety, concurrency efficiency, and maintainability. Additionally, the planned self-diagnosis subsystem will enable automatic aggregation of fault statistics and health metrics for each firmware release, supporting informed rollback, targeted bug fixing, and progressive rollout strategies. These capabilities will reinforce long-term maintainability and simplify lifecycle management for large deployments.

Overall, the results confirm that the proposed system is robust, extensible, and suitable for scalable IoT use cases. With future integration of multi-protocol delivery, secure build pipelines, and automated release diagnostics, the architecture provides a strong foundation for dependable and sustainable OTA updates in modern, distributed IoT ecosystems.