Abstract

The functional performance of porous metals and alloys is dictated by pore features such as size, connectivity, and morphology. While methods like mercury porosimetry or gas pycnometry provide cumulative information, direct observation via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) offers detailed insights unavailable through other means, especially for microscale or nanoscale pores. Each scanned image can contain hundreds or thousands of pores, making efficient identification, classification, and quantification challenging due to the processing time required for pixel-level edge recognition. Traditionally, pore outlines on scanned images were hand-traced and analyzed using image-processing software, a process that is time-consuming and often inconsistent for capturing both large and small pores while accurately removing noise. In this work, a software framework was developed that leverages modern computing tools and methodologies for automated image processing for pore identification, classification, and quantification. Vectorization was implemented as the final step to utilize the direction and magnitude of unconnected endpoints to reconstruct incomplete or broken edges. Combined with other existing pore analysis methods, this automated approach reduces manual effort dramatically, reducing analysis time from multiple hours per image to only minutes, while maintaining acceptable accuracy in quantified pore metrics.

1. Introduction

Metal foams (i.e., porous metals) have a wide variety of applications, including automotive, aerospace, biomedical, and many more [1,2,3]. All of these applications are determined by whether the pores are highly interconnected with each other (coalescence) and the surface (percolation), which is dependent on the processing method. Individual metals and alloys often require different processing routes, so it is crucial to ensure that the foaming process yields the desired results. Metal foams can be prepared and characterized in many ways, depending on the scale and quantity of the pores [4,5]. For instance, porous metals made by liquid-state foaming may have millimeter-scale pores [6], while de-alloyed metals may have pores that are only nanometers in size [7,8]. Some porous metals are even constructed by including hollow spheres, such that the porosity is directly controlled in size and morphology [9]. These variations in processing determine the pore quantity, size, and morphology, which determine the appropriate applications. With such variety possible, it is critical to accurately characterize the pores so that the effects of processing on porosity and the effects of porosity on performance can be successfully determined.

Given the many possible manufacturing routes and potential pore conformations, it would be expected that analysis methods are equally diverse, but the preparation often follows the same basic steps. The material is sectioned to reveal the interior structure, and as needed, the cross-section is further smoothed to improve the accuracy of pore quantification. For large pores, sample preparation can be done by basic methods such as mechanical polishing, or in some cases, X-ray computed tomography (X-ray CT) can be used without any sample preparation, depending on the sample size and material [10]. For microscale and nanoscale pores [11], final vibratory polishing, focused ion beam milling (FIB), and/or transmission electron microscopy may be necessary to preserve sub-micron features in the pore structure that may be distorted or destroyed with more aggressive polishing techniques. To help balance the volume limitations of FIB with the resolution limits of X-ray CT, 3D pore reconstruction using newer plasma FIB techniques has been demonstrated [12], but the time and cost for analysis are still relatively prohibitive.

The Additive Expansion by Reduction of Oxides (AERO) process was used here to produce a microporous structure [13]. This method results in a distribution of non-uniform pore sizes typically less than 10 μm in diameter as a circular equivalent. This makes the preparation and analysis of these pores somewhat challenging. To characterize the porosity, surface area, pore size, and pore distribution, ImageJ or similar software is used to quantitatively analyze metal foams using images collected from a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Due to the uneven pore morphology, these images cannot be directly input into current software tools and processed. Rather, physically tracing the pores by hand is necessary before inputting them into ImageJ to produce the correct results (e.g., [14]). This process can be time-consuming and prone to human error. Automated edge-recognition methods, though often unreliable in existing software, could substantially reduce analysis time while improving accuracy.

In this paper, we present a software tool, PORUS (Version 1.0), designed to automate and streamline the analysis of pores in SEM images. Section 2 shows the user interface of PORUS and its main functionalities. Section 3 describes the traditional methodologies of procuring and analyzing images, followed by the new algorithm for pore identification and characterization. Section 4 presents the results of the software, compares them to the old methodology, and discusses the results, potential applications, and limitations of the new software tool; some concluding remarks follow this in Section 5. In general, PORUS was able to save significant time in image preparation while increasing the success rate and accuracy of pore recognition when compared to hand-tracing and ImageJ analysis.

The main research contributions of this work are as follows: (1) PORUS, a new software framework for the automated identification and quantification of pores in SEM images of metals. (2) A configurable preprocessing and edge-detection pipeline (including contrast adjustment, thresholding, denoising, and blur) that addresses the unique challenges of noisy, irregular SEM micrographs. (3) Quantitative and qualitative validation by comparing PORUS with traditional hand-tracing and ImageJ workflows, showing that it produces reproducible results with far less manual effort. (4) A user-friendly interface that enables real-time parameter tuning, allowing for consistent pore analysis across batches of images.

2. PORUS User Interface and Functionalities

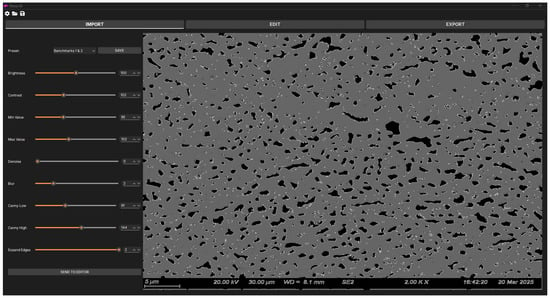

PORUS allows a user to load raw SEM images (i.e., unprocessed), display them on the user interface, and interact with the user during the pore detection process. Figure 1 shows the first PORUS user interface, where the user imports an SEM image (on the right) and adjusts the parameters of the pore detection algorithms (on the left). When the user adjusts the parameters, PORUS updates the image in real time to show the changes in pore outlines identified by the algorithm. These settings can be saved as a preset, allowing users to reuse the settings on future images easily. This feature is particularly useful when processing images of the same batch, which often use the same or very similar settings.

Figure 1.

PORUS user interface section for importing an SEM image and adjusting parameters for pore detection algorithms.

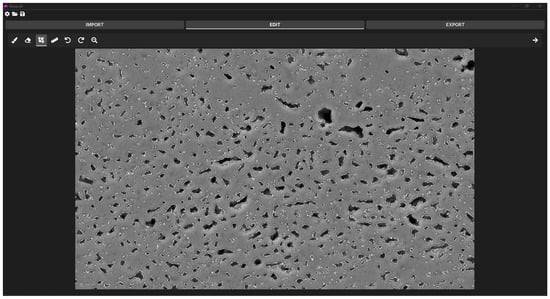

After pore detection by the algorithm, the user can use the second section of PORUS (Figure 2) to edit the outlined image to add missing pore outlines or to remove outlines incorrectly detected by the algorithm. The user can also crop the image and set the scale of the image to automatically convert pixels to the desired units.

Figure 2.

PORUS user interface section where users can crop the image, set the scalebar, and add or remove outlines.

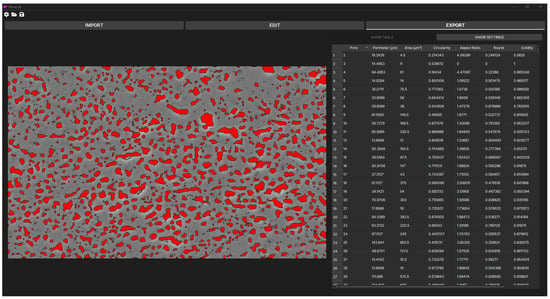

The final section of PORUS allows the user to view the final processed image with enhanced contrast of all the detected pores and export the pore characteristic data (Figure 3). On the displayed image (left), PORUS allows the user to hover over a pore to display its data. On the right, the user can toggle between the table of pore data and pore threshold settings. The pore threshold settings allow users to adjust the characteristics by which the pores are counted. For example, the user may want to ensure the pores detected by the software only count towards the overall data if their circularity is above 15%. In this case, the user would adjust the minimum acceptable circularity threshold to 0.15. The pore data shown in the table can be sorted in the app. Additionally, the user can select data in the table by double-clicking a row, and the corresponding pore will be highlighted in the image shown on the left. Finally, pore characteristic data can be exported/saved to files for further processing or other usage.

Figure 3.

PORUS user interface section where users can view the results, filter out pores, and export results.

3. Methodology

3.1. Material Preparation

The samples used for imaging started as a powder with a chemical composition of Cu 2 mol% CuO. The mixture consisted of high-purity copper (Cu, 99%, <75 μm, Sigma-Aldrich #2007780, St. Louis, MO, USA) and cupric oxide (CuO, 98%, <10 μm, Sigma-Aldrich #208841), which were milled for 90 min to optimize the foaming characteristics [13].

From this batch, 1g of the powder was weighed out and then put into a 6-mm diameter die and punch. The powder was then pressed at 1 GPa with a 30 s dwell time at room temperature using an electronically controlled hydraulic press (Carver Inc., Auto Pellet Press Model 4387, Wabash, IN, USA). The sample was then foamed in a single-zone tube furnace (Across International STF1200, Livingston, NJ, USA) for one hour at 600 °C while flowing 0.4 L/min 5% hydrogen diluted in argon.

The sample was then cross-sectioned with a low-speed diamond saw (Allied High-Tech Productions Inc., Cerritos, CA, USA, Tech Cut 4X), cold-mounted in epoxy (Allied High-Tech Productions Inc., Cerritos, CA, USA, p/n 145-20005), polished by hand incrementally using progressively finer SiC abrasive papers up to 1200 grit, followed by a 1 μm Al2O3 slurry. Finally, the sample was vibratory polished (Pace Technologies, Giga-0900, Tucson, AZ, USA) for four hours using a 0.05 μm Al2O3 slurry. The sample was then imaged in a Zeiss Sigma 500VP SEM (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Oberkochen, Germany) using an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. The images used in this process were collected at a magnification of 2000× and a resolution of 2048 × 1536 pixels.

3.2. Current Methodology of Image Tracing and Processing

The currently used software tool for image processing, ImageJ, cannot process raw SEM images to correctly identify pore edges and quantify pore characteristics, as it heavily relies on hand-tracing of pores to enhance their edge contrast. This requires micrographs to be printed on standard letter-size sheets (ANSI A), and pores to be traced using an ultra-fine tip marker to achieve strong edge contrast. The physical copies were then scanned at 600 dpi (5100 × 6600 pixels) to create digital image files. For comparison, both traced and untraced images were processed in ImageJ by manually adjusting brightness and contrast to emphasize pore edges accurately, made binary, and processed using the “Analyze Particles” function of ImageJ (version 1.53k). Pores on edges of the micrograph, with an area of less than 0.02 μm2 (~500 nm circular equivalent diameter pore), and/or with a circularity less than 0.15, were excluded from analysis. The pore area was converted to diameter using the equivalent circular cross-section. All error bars calculated in this work represent one standard deviation from the mean.

3.3. New Methodology for Image Processing

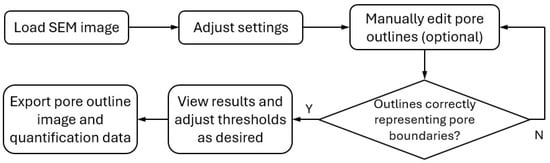

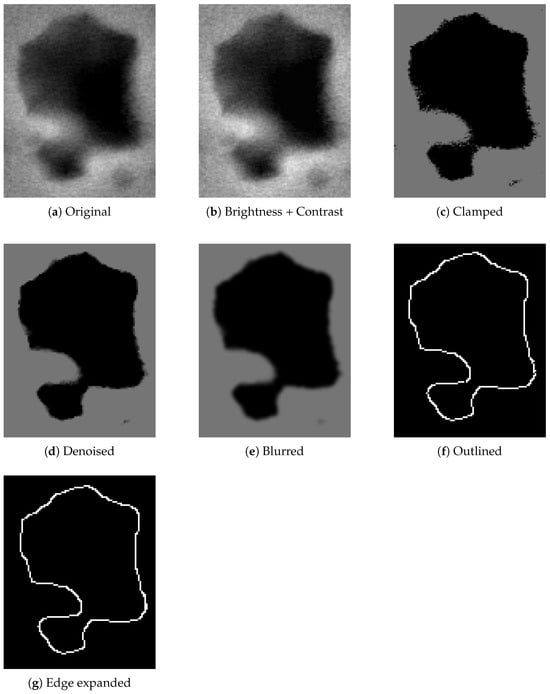

The new software tool, PORUS, can process the original SEM images for pore identification and characterization without the need for hand-tracing. PORUS uses a combination of techniques to perform image manipulation, Gaussian blur, canny edge detection, morphological closing, and final clean-ups. Figure 4 illustrates the workflow for using PORUS. Figure 5 illustrates a pore undergoing each phase of processing, demonstrating the logical process by which PORUS detects the edges of a pore.

Figure 4.

User workflow for using the PORUS software.

Figure 5.

The software algorithm process demonstrated on an example pore.

3.3.1. Image Manipulation

PORUS uses both convolutional image manipulation and intensity manipulation to identify the outlines of the pores in an SEM image. SEM images vary significantly in terms of image complexity, lighting, and noise, so these manipulation techniques are required to prepare the outlines of the pores for edge detection.

Convolutional image manipulation techniques apply a matrix (known as a kernel or filter) across the pixels of an image to modify their values based on their surrounding neighbors. These techniques are used to target and enhance or suppress specific features, such as noise, texture, or edges.

Intensity image manipulation techniques directly modify the values (intensity) of the pixels in an image. While convolution techniques modify pixel values based on their neighbors, intensity techniques only consider the value of the pixel being modified. These techniques focus on enhancing the visibility of certain features, correcting poor lighting, and normalizing data by removing noise and outliers.

PORUS allows the user to adjust each manipulation step, enabling the user to adapt the image and algorithm for optimal detection of the pore outlines. These steps include brightness and contrast adjustment, clipping pixel intensity, denoising strength, Gaussian blur strength, hysteresis thresholding values, and edge thickness.

Intensity Clipping and Brightness/Contrast Adjustment

The method for detecting edges relies on the contrast in an image. An ideal SEM image would be perfectly black and white, allowing pores to be easily distinguished from non-pores. In reality, SEM images have a wide range of values, and pores can exhibit multiple shades, which can pose a significant challenge for edge detection. Thus, increasing image contrast and/or brightness and enforcing minimum and maximum thresholds can help distinguish the pores from the rest of the image and increase accuracy in edge detection.

First, brightness and contrast are applied to each pixel in the image to calculate the new pixel intensity by the following:

where is the contrast ranging from 0 to 2, is the brightness ranging from to 255, and v is the intensity (value) of the pixel, ranging from 0 to 255.

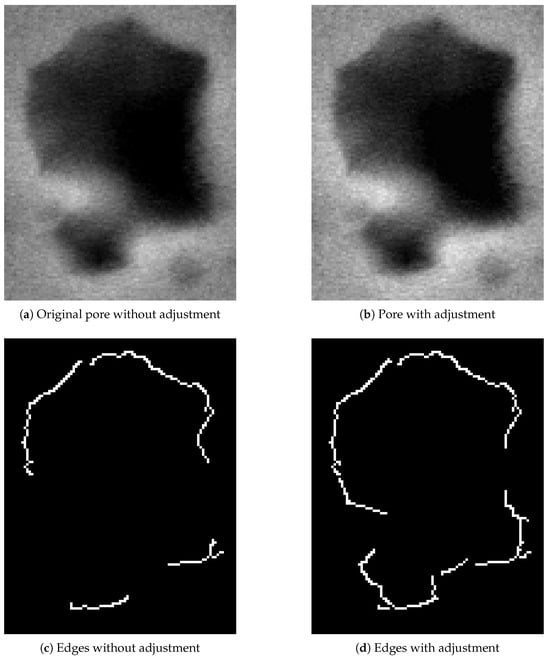

Adjusting the brightness and contrast of the pores may not appear to cause significant changes to the pores, as shown in Figure 6a,b, but it makes a significant difference for edge detection. Figure 6c and Figure 6d show the pore edges after running basic canny edge detection on the two images shown in Figure 6a and Figure 6b, respectively. It can be seen from Figure 6 that the pore with the brightness + contrast adjustments yields a more accurate outline than the one without the adjustments.

Figure 6.

Comparison of images with and without applying “Brightness + Contrast” adjustment–base images vs. edge detected.

After “Brightness + Contrast” adjustment, the new intensity value of each pixel is then “clamped” to values between a minimum and maximum threshold set by the user:

Any pixels with an intensity value below the minimum will be set to the minimum; any pixels with an intensity value above the maximum will be set to the maximum; any pixels in between will remain unchanged. Figure 7 shows the comparison of pores before and after clamping, and the corresponding detected pore edges.

Figure 7.

Comparison of pore edge detection before and after clamping.

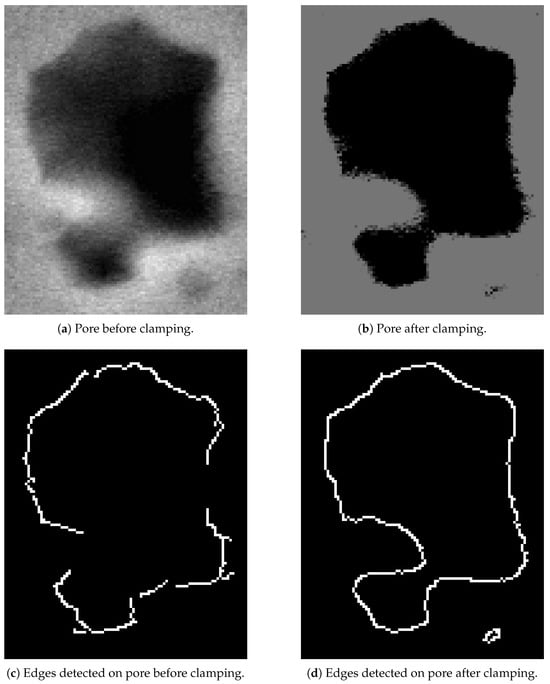

Median Blur (Denoising)

Once the pixel intensities are appropriately adjusted, a median blur is applied to reduce noise in the image by removing tiny speckles or isolated pixels. Since these pixels are not part of the pore outlines, they should be removed so that the edge-detection algorithm does not incorrectly identify them as pore outlines.

Median blur works by replacing each pixel of an image with the median of its neighboring pixel values within a particular region, determined by a user-specified kernel. Median blur is particularly adept at preserving edges while removing small-scale noise, making it especially useful for clarifying the edges of the pores in the SEM images.

Figure 8 shows the comparison of pores before and after applying denoising to the clamped image from the previous step. It can be seen that this process smooths out the outline and removes noise.

Figure 8.

Comparison of pore edge detection before and after denoising.

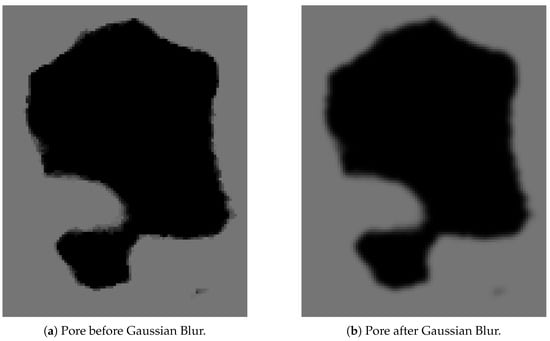

Gaussian Blur

After median blur removes noise in the form of tiny speckles, Gaussian blur is applied to smooth out the transitions in and around pores. Since images typically have soft gradients in and around the boundaries of the pores caused by variations in the surface, lighting, and/or depth, applying a Gaussian blur can help smooth out these transitions to make it easier for the edges to be detected.

Gaussian blur reduces the noise of the image by adjusting the values of neighboring pixels, thereby helping to create more recognizable edges that the algorithm can detect. This is achieved by using a Gaussian kernel, a two-dimensional function derived from the Gaussian distribution:

where x and y are the coordinates of the pixel and is the standard deviation of the distribution, which determines the spread of the weights and overall strength of the blur. Applying this kernel to the image takes the weighted average of each pixel and its neighbors, resulting in a smoother image with reduced detail and noise. SEM images often provide a level of detail that makes it harder for edge detection algorithms to find the outlines, so Gaussian blur helps to reduce this detail and makes the image digestible to the edge detection algorithm.

Figure 9 shows the pore comparison before and after applying a Gaussian Blur. It can be seen from Figure 9a,b that Gaussian Blur smooths out the rough boundary, which results in a smoother outline after edge detection as shown in Figure 9c,d. It was observed on other pores that pore edges were significantly improved after applying a Gaussian Blur. Furthermore, the stray line at the bottom right of the images is reduced in size (Figure 9a,b) so that it is not counted as a pore. This is another reason that Gaussian Blur is applied.

Figure 9.

Comparison of pore edge detection before and after Gaussian Blur.

3.3.2. Canny Edge Detection

Now that the image has been prepared, PORUS uses canny edge detection to find the outlines (edges) of the pores in the SEM image. This process, created by John Canny [15], uses four steps: gradient calculation, magnitude and direction calculation, non-maximum suppression, and thresholding.

First, the intensity gradients of the image are calculated by finding the image’s intensity gradients, which locate regions with rapidly changing intensities (i.e., edges). This works by using a Sobel filter, which is a type of discrete differentiation operator that finds the intensity gradient of an image by taking two filters, one for the x-axis and one for the y-axis, and convolving over the image.

The Sobel filter kernel is defined as follows:

Next, the x and y gradients ( and , respectively) are used to calculate the magnitude and direction of each pixel’s intensity change. The magnitude is calculated by the following:

which represents how strong the change in intensity is. The direction is calculated by the following:

which gives the direction angle with respect to the x-axis of the steepest increase in pixel intensity.

These values are then used to classify what is and is not an edge. Although only the boundary of the edge is desired, this method can often result in edges with very thick parts, and non-maximum suppression is needed to fix this issue.

Non-maximum suppression works by taking the magnitude and direction calculated from the Sobel filter, as defined in Equation (4), and classifying it in one of four possible directions: 0° (horizontal), 45° (diagonal), 90° (vertical), and 135° (anti-diagonal). Then, each pixel’s magnitude is compared to the two neighbors in the classified direction. If its magnitude is not the largest, it is set to 0 so that it gets suppressed.

This process results in clear, fine lines that represent the edges of the pore. However, it can also result in some weak or isolated edges, which require Hysteresis Thresholding to fix.

Hysteresis Thresholding filters edges into three categories: strong, weak, and non-edge, based on two thresholds: high and low, as determined by the user. Each edge is evaluated, and if the magnitude of the edge is greater than the high threshold, it is a strong edge. It is a weak edge if the magnitude is between the high and low thresholds. The edge is removed if its magnitude is below the low threshold. Strong edges are kept, and weak edges are kept only if they are attached to a strong edge. This process results in edges outlining the pores of the SEM images.

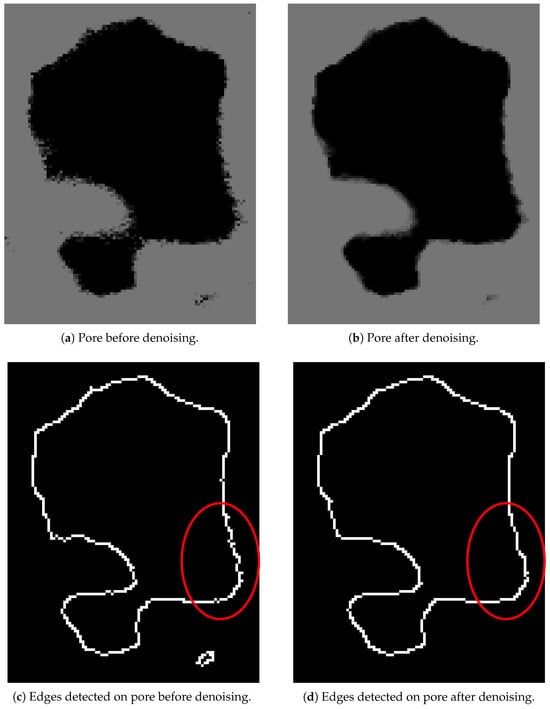

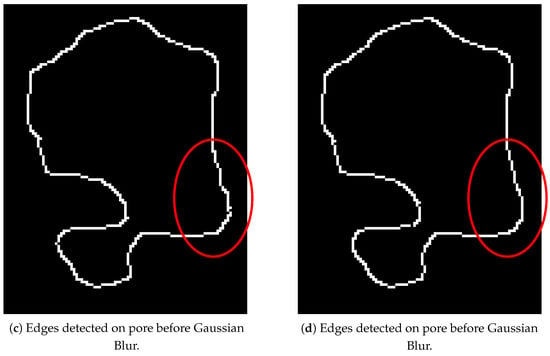

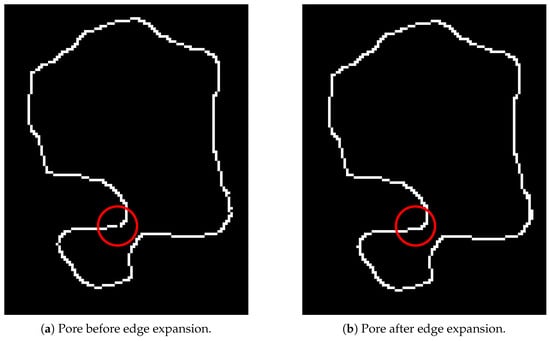

3.3.3. Morphological Closing

After the edges of pores are detected, a morphological closing is applied. This process uses dilation and erosion to close the detected edges that are close but not fully closed. First, dilation is applied to enlarge and connect the edges to other close edges. Then, erosion is applied to restore the edges to their original thickness, but leave the new connections created.

The process is vital to repair any broken or not fully connected edges caused by noise or other variations in the SEM image. Closing the edges allows the software to calculate the qualities of the pores.

The difference can be seen in Figure 10 where a small connection is formed to close off the outline.

Figure 10.

Comparison of pore edges before and after morphological closing.

3.3.4. Clean Up

Although morphological closing closes most of the remaining pores that should be closed, sometimes, there are a few pores left unclosed. To solve this issue, the endpoints of each outline are calculated and evaluated to see if any of them are pointed towards another within a certain distance. Any endpoints that meet this criterion are connected.

3.4. Pore Characterization

After connecting all the lines (edges) necessary to form pores, PORUS calculates the perimeter, area, circularity, aspect ratio, roundness, and solidity of each pore using equations in the following sections.

3.4.1. Perimeter

Because all the resultant pores are solely made up of outside lines without interior lines, the perimeter of a pore can be calculated as the sum of the lengths of all edges. The lengths of the edges can be calculated using the Euclidean distance formula [16] given by the following:

where are the vertices of the pore and is the Euclidean distance between two vertices and is calculated by the following:

3.4.2. Area

The area of a polygon can be calculated using the Shoelace Theorem [17], also known as the Gauss Area Formula, using the coordinates of its vertices. Assuming the vertices of the polygon (pore) are (, ), (, ), ..., (, ), then the area can be calculated by the following (note that Equation (9) only works when the vertices are in order, either clockwise or counterclockwise):

Depending on the aspects of a pore, the diameter of a perfect circle with the same area as the pore can be helpful when analyzing the sizes of pores in the SEM image. The diameter is calculated as follows:

3.4.3. Circularity

Circularity defines how closely the shape of the pore resembles a circle; it can be calculated by the ratio of the pore’s area to the area of a circle with the same perimeter as the pore [18,19]. The formula defining circularity is given by the following:

3.4.4. Aspect Ratio

The aspect ratio of the pore measures how elongated it is compared to a perfect circle, which would have an aspect ratio of 1 [19]. The aspect ratio of the pore is calculated by the following:

An ellipse is fitted over the pore to find the axis lengths using the least-squares approach [20,21]. The longer axis is referred to as the Major Axis (), and the shorter axis is the Minor Axis ().

3.4.5. Roundness

The roundness of a pore defines how closely the area of a pore is to the area of an outfit circle [19]. It is calculated by the following:

3.4.6. Solidity

Solidity measures how compact a pore is by comparing the area of the pore to the area of the convex hull of the, as defined by the following:

where is the area of the convex hull of the pore.

The convex hull of a shape is determined by the smallest possible convex polygon that completely encloses the shape [21]. PORUS uses the OpenCV library [22] to calculate the convex hull. This library typically uses Andrew’s Monotone Chain, which splits the polygon into its upper and lower halves. For the lower half, it moves from left to right, and at each step, it checks whether adding the point would make the shape concave; if it would, the previous point is removed to ensure the shape remains convex. The process is the same for the upper half, except that the algorithm moves right to left.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Discussion

Although PORUS uses existing techniques for edge detection, these techniques often require “clean” images and struggle to handle the complexity of SEM images, which can be very noisy, have poor contrast, and contain many irregularly shaped pores, making the detection of pore edges significantly more difficult. For example, the Canny algorithm has been widely used for detecting pore segmentation, as it is capable of detecting boundaries with very high precision [23]. Furthermore, standard segmentation methods, such as global thresholding, adaptive thresholding, and watershed algorithms, are often insufficient and unable to handle the inherent variability found in SEM images.

PORUS was developed to overcome the challenges of existing techniques. Its novel and configurable pipeline for edge detection allows the user to adjust each step of the image preprocessing (contrast, pixel value clamping, blur, etc.). With this feature, users can fine-tune the software to work with the unique properties of their SEM images, rather than relying on fixed, prescribed thresholding techniques. Furthermore, PORUS implements post-processing techniques, such as non-maximum suppression, morphological dilation, and closing, to improve edge clarity without over-segmentation, and uses vectorization to connect endpoints that were not connected by the previous techniques but should be.

Unlike machine-learning-based systems that need large datasets and heavy computational power for training, PORUS can produce accurate results using a series of deterministic algorithms and techniques that ensure reproducibility and adaptability for workflows involving different porous materials.

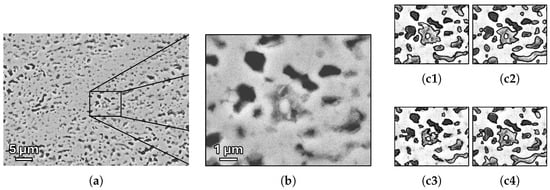

4.2. Qualitative Observations in Hand Tracing

Hand tracing is time-consuming and requires subjective judgment to properly identify pore boundaries. Its accuracy also depends on magnification, since the smallest identifiable pore size is limited by the physical line width of the tracing tool. The placement of the bounding line will also vary for each person, as they will have varying levels of discretion and accuracy in the tracing process. For instance, the image and area highlighted in Figure 11a provides an example of well-defined and poorly defined pores. While the black pores at the upper left of Figure 11b show a high degree of uniformity, the central pore and those to the bottom right have less defined edges and higher variability, as demonstrated in Figure 11c1–c4. Invariably, different people will consider pore boundaries slightly differently from one another, leading to variations in pore outlines. These variations not only affect the calculations of each pore, but also affect what is considered a pore, as, if outlines of two pores touch at any point, they will be considered as one pore.

Figure 11.

Illustration of variations in hand-tracing of pore edges. (a) Original image; (b) magnified image of highlighted area; and (c) examples of four different individual hand-tracings of pore boundaries.

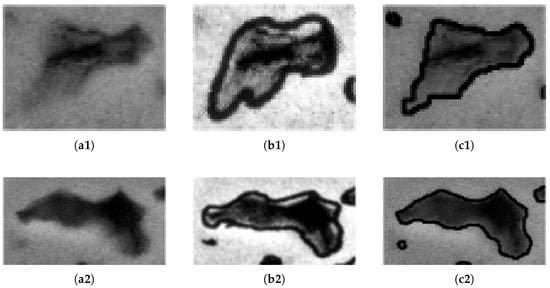

Figure 12 shows a comparison of ImageJ with hand-tracing and PORUS used on three pores from an SEM image. As seen in Figure 12, PORUS consistently provides a more precise and well-defined outline of the pores found in the SEM image. In contrast, ImageJ based on hand-traced images introduce noticeable alterations and distortions to the original image, which affect the final results and the overall integrity of the data calculated using this method. For example, the pore at the top-left corner identified by PORUS (Figure 12(c1)) was not identified by ImageJ (Figure 12(b1)), because the pore was not fully enclosed in the hand-traced images due to human error. Since PORUS uses the SEM image directly, the image and pores remain unaltered when the pore outlines are calculated, which increases the overall accuracy of the pore data extracted from the SEM images.

Figure 12.

Comparison of pore outlines by hand-tracing and PORUS. (a) Original SEM images; (b) hand-traced images; and (c) PORUS processed images.

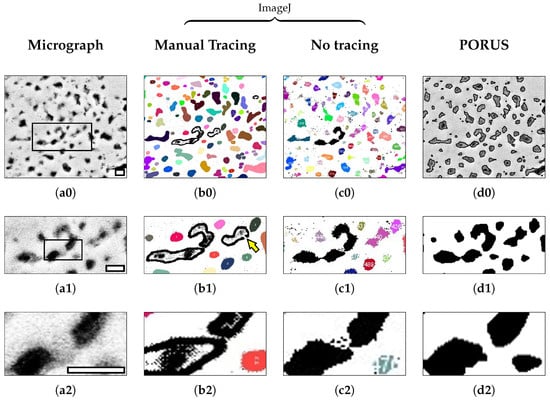

PORUS has two primary advantages over using hand-traced images and ImageJ. First, PORUS is much faster because it does not require the user to manually outline all of the pores by hand before performing analysis. The second advantage is demonstrated in Figure 13. Taking a look at Figure 13(b0), it is clear that the two pores are touching, even though they should not, as seen in Figure 13(a0). PORUS, however, does not have this issue, as it correctly outlines the two pores while keeping them separate. Because PORUS uses the canny edge detection algorithm to detect the edge, it is much finer in its selection of the edge so that edges do not bleed into one another, as can happen when manually tracing the pore outlines with a marker.

Figure 13.

Comparison of edge quality near a small feature with poor contrast as viewed at increasing magnifications of the (a0) original micrograph and corresponding pore detection after (b0) manual tracing and processing in ImageJ, (c0) processing in ImageJ without manual tracing, and (d0) applying automated edge detection using the PORUS algorithm. Boxed area in (a0) highlights image in (a1), and boxed area in (a1) highlights image in (a2) as well as corresponding images in (b0–d0). Scale bars in (a0–a2) each represent 1 μm.

The areas of poor edge contrast are particularly interesting for comparing manual segmentation with automated edge detection. In the final analysis, the definition of the pore edges is determined on a per-pixel basis and are highly sensitive to the image processing and algorithmic approach. As shown in Figure 13, manual tracing (Figure 13(b0)) tends to produce pore outlines that are smoother than those produced without manual tracing when comparing ImageJ analysis (Figure 13(c0)), since the tracing implementation does not have single-pixel resolution. The traced border also tends to estimate a slightly larger pore area as the ink bleeds to both sides of the identified pore edge (e.g., Figure 13(b2) vs. Figure 13(c2)). Both ImageJ and PORUS require closed outlines to recognize pores; therefore, any perimeter with a gap (see arrow in Figure 13(b1)) will not be identified as a pore. Pores are further filtered by circularity, as described in Section 3.2. Neither set of pores in Figure 13(b2) or Figure 13(c2) is included in their respective quantifications, as the circularity also limits inadvertent pore connections, as highlighted in that example.

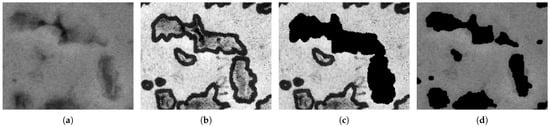

PORUS addresses these challenges in a few ways. First, PORUS does not require hand-traced outlines, which often overestimate the edge of the pore due to the size of the pen and visual requirements. Instead, it computes changes in pixel intensity directly in the SEM image to find these pores. Because these outlines are more accurate representations of the true pore outline, it is less likely that pores will be clumped together and registered as a single pore when they should be considered multiple pores. See the example in Figure 14, which demonstrates the increased accuracy of PORUS.

Figure 14.

Comparison between a set of pores to demonstrate issues with connecting multiple pores. (a) Original SEM image; (b) hand-traced image; (c) hand-traced image processed through ImageJ; and (d) image processed with PORUS.

Furthermore, as seen in Figure 13, the process using ImageJ will not connect pores that are not fully connected; even the slightest gap in the outline will cause a pore not to be calculated correctly. PORUS uses vectorization to overcome this challenge. By finding the endpoints of a pore outline, PORUS can check whether or not those endpoints should form a pore or not, and, if they should, PORUS will connect those points and close the pore.

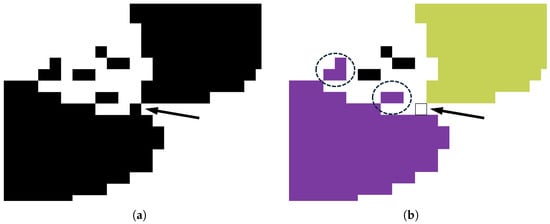

The importance of image processing for edge detection is further highlighted in the ImageJ example of Figure 13(c0) by demonstrating the effect of a single pixel in Figure 15. In this case, black pixels indicate areas not included in the pore quantification using ImageJ. As shown in Figure 13(c1), this excludes a significant amount of pore area. When the pixel highlighted by the arrow in Figure 15a is removed, the two pores are now included in quantification (Figure 15b). The inclusion of any pixel that shares even a single corner with the parent pore is highlighted by the circled areas in Figure 15b, and this is an important aspect of the original image resolution and the image processing choices. Furthermore, because of the complex three-dimensional shape of the pores and the edge effects possible when using electron microscopy [24], it is subjective as to whether the removal of the pixel in this example is warranted or if the edge is excessively degraded and more pixels should be added. The latter may be more appropriate in some circumstances since certain pores, such as those seen in the bottom right of Figure 13(c2), are poorly resolved.

Figure 15.

Demonstration of how one pixel can affect pore size estimation from Figure 13(c2). (a) Before removal, the pixel indicated by the arrow in the image creates a large pore with very low circularity that is not included in pore quantification. (b) When removed, the pores are both included in pore quantification. Circled areas in (b) demonstrate how stray pixels will be included in any pore they touch. Black pixels are not included in pore analysis.

4.3. Quantitative Comparison of Manual and Automated Techniques

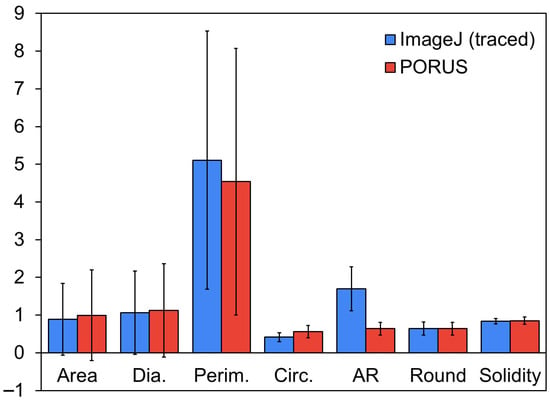

The identification of pores can be challenging for both manual tracing automated edge detection due to the low contrast of many pores, which makes it difficult to discern true pore edges. To assess the reliability of the hand-traced images, each image was traced at least nine times by different individuals, and the results were averaged to calculate a standard deviation for each quantified category. This standard deviation defines the acceptable output range for automated pore analysis. As shown in Figure 16, PORUS and ImageJ produce results that fall within this range and are largely consistent with hand-tracing across all six features analyzed. While the quantitative outputs of PORUS and ImageJ are comparable, the main distinction lies in workflow efficiency: PORUS significantly reduces the time required for pore identification compared with ImageJ, making it a faster yet equally reliable option for pore analysis.

Figure 16.

SEM Image 1 data comparison between hand-traced (ImageJ) and PORUS with pore distribution (error bars). Area, diameter, and perimeter are in units of μm.

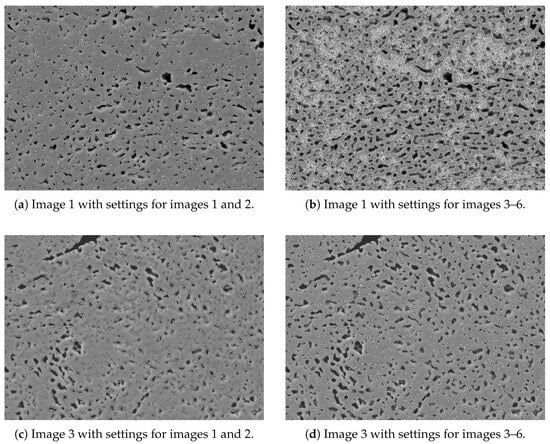

4.4. Sensitivity of Parameter Selection

The accuracy of pore outlines depends on several tunable parameters, primarily brightness and contrast adjustments and clamped thresholds. When analyzing the images 1–6 during the development of this software, certain settings worked best for images 1 and 2 and not for images 3–6 and vice versa. Figure 17 demonstrates the necessity of using different settings for different images.

Figure 17.

Comparison of detected pores between images processed with different settings.

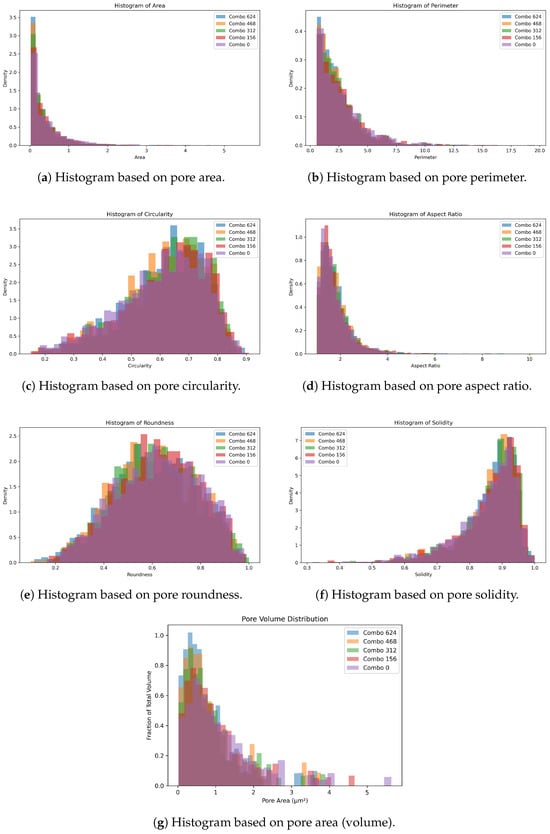

A sensitivity analysis was performed to determine how different settings affect the results. A total of 625 combinations of setting values were used, Figure 18 shows five of the combinations. Those combinations are in Table 1. The settings used in Combo 312 were the baseline values used to test Image 1 previously, the other values are ±10% of the baseline. As seen in Figure 18, PORUS calculates pore metrics similarly with a variety of settings.

Figure 18.

Histograms for pore metrics.

Table 1.

Settings used in Figure 18.

5. Conclusions

The current process of analyzing scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images requires significant manual preparation, such as hand-tracing pore outlines, and introduces inconsistencies that can compromise accuracy of the results and analysis. The software tool PORUS was created to solve this problem by providing an efficient means for analyzing SEM images. Through its user-friendly interface, PORUS allows users to analyze SEM images in just a few minutes. Users can import an SEM image, adjust preprocessing settings to optimize handling of image-specific conditions, and automatically outline and extract pore outlines using a robust edge detection and analysis pipeline. PORUS can calculate and export pore characteristics, including area, perimeter, aspect ratio, and solidity, within seconds. This significantly improved workflow enables students and researchers to perform pore analysis more accurately and much faster than using existing tools. Future work may involve further improving pore outline accuracy and expanding the types and diversity of pores that can be analyzed using this software tool. Specifically, implementing a feature for automatically determining the optimal preprocessing settings would greatly enhance speed and reproducibility while reducing user input. Such a feature would lend PORUS to be adopted into industrial workflows, where the ability to rapidly and accurately characterize pores is critical for quality control, high-throughput screening, and integration into manufacturing pipelines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and M.A.; methodology, M.M. and M.A.; software, M.M.; validation, M.A., O.F. and J.V.; formal analysis, M.A.; data curation, M.M., M.A., O.F. and J.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M., M.A. and H.F.; supervision, M.A. and H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data and code presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the students of ENGM 310–Materials Engineering who participated in manual pore tracing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

References

- García-Moreno, F. Commercial Applications of Metal Foams: Their Properties and Production. Materials 2016, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Mitra, I.; Avila, J.D.; Upadhyayula, M.; Bose, S. Porous metal implants: Processing, properties, and challenges. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2023, 5, 032014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; Alnaser, I.A. A Review of Different Manufacturing Methods of Metallic Foams. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 6280–6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banhart, J. Manufacture, characterisation and application of cellular metals and metal foams. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2001, 46, 559–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwater, M.A.; Guevara, L.N.; Darling, K.A.; Tschopp, M.A. Solid State Porous Metal Production: A Review of the Capabilities, Characteristics, and Challenges. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018, 20, 1700766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JIANG, B.; ZHAO, N.; SHI, C.; LI, J. Processing of open cell aluminum foams with tailored porous morphology. Scr. Mater. 2005, 53, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.; Gan, J.B. Nanoporous metals processed by dealloying and their applications. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2018, 5, 1141–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.J.; Han, J.; Chen, Q. Nontraditional dealloying methods, novel nanoporous materials, and new opportunities. MRS Bull. 2025, 50, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiei, A.; Lattimer, B.Y.; Bearinger, E. Recent Advances in the Analysis, Measurement, and Properties of Composite Metal Foams. In Proceedings of the Metal-Matrix Composites; Srivatsan, T.S., Harrigan, W.C., Jr., Hunyadi Murph, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Elmoutaouakkil, A.; Salvo, L.; Maire, E.; Peix, G. 2D and 3D Characterization of Metal Foams Using X-ray Tomography. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2002, 4, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwater, M.A.; Darling, K.A.; Tschopp, M.A. Synthesis, characterization and quantitative analysis of porous metal microstructures: Application to microporous copper produced by solid state foaming. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2016, 3, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, R.; Mizuta, Y.; Kato, T.; Kimura, T. Comparison of large-volume 3D reconstruction using plasma FIB-SEM and X-ray CT. Microscopy 2024, 73, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, J.E.T.L.; Rutherford, A.P.; Learn, R.S.; Atwater, M.A. Parametric Study of Planetary Milling to Produce Cu-CuO Powders for Pore Formation by Oxide Reduction. Materials 2023, 16, 5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Kun, J.T.L.; Patterson, E.; Allapatt, N.; Atwater, M. Hybrid Pore Formation in Copper Spheres by Gas Entrapment and Oxide Reduction. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2301198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canny, J. A Computational Approach to Edge Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1986, PAMI-8, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D. Precalculus: A Problems-Oriented Approach; Cengage Learning; Brooks Cole: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Braden, B. The Surveyor’s Area Formula. Coll. Math. J. 1986, 17, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, E.P. A Method of Assigning Numerical and Percentage Values to the Degree of Roundness of Sand Grains. J. Paleontol. 1927, 1, 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgibbon, A.; Pilu, M.; Fisher, R. Direct least square fitting of ellipses. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1999, 21, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R. An efficient algorith for determining the convex hull of a finite planar set. Inf. Process. Lett. 1972, 1, 132–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Kleist-Retzow, F.T.; Tiemerding, T.; Elfert, P.; Haenssler, O.C. Automated Calibration of RF On-Wafer Probing and Evaluation of Probe Misalignment Effects Using a Desktop Micro-Factory. J. Comput. Commun. 2016, 4, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papia, E.M.; Kondi, A.; Constantoudis, V. Machine learning applications in SEM-based pore analysis: A review. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2025, 394, 113675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y. Materials Characterization; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).