Extended Reality as an Educational Resource in the Primary School Classroom: An Interview of Drawbacks and Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Method

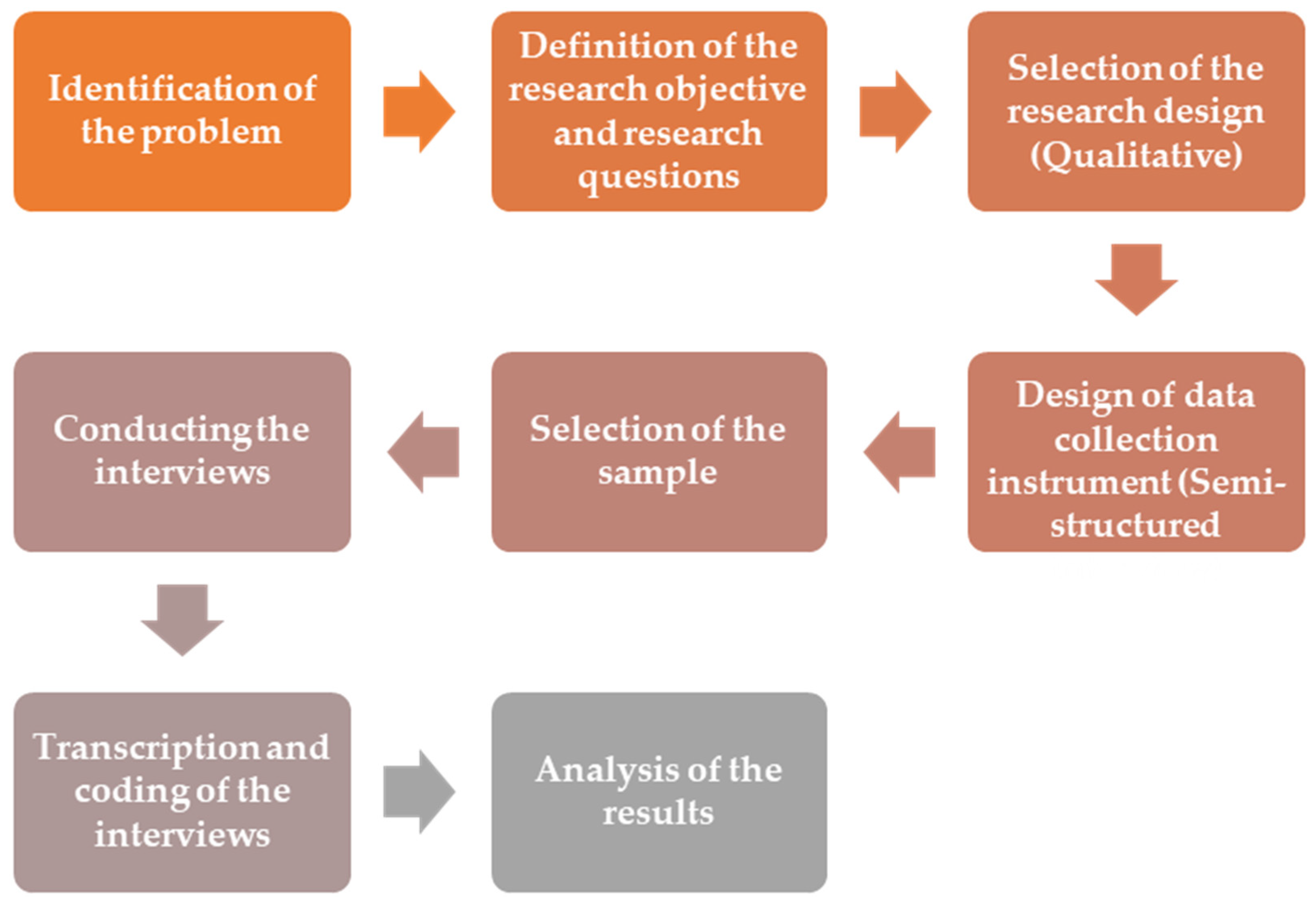

3.1. Design

3.2. Sample

3.3. Data Collection Instrument

- Have taught subjects such as “Educational Technology”, “New Technologies applied to Education” or “Information and Communication Technologies applied to Education” in academic institutions.

- Have training in the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and applied Emerging Technologies.

- Have published relevant research in academic journals or specialised conferences in the field of Emerging Technologies and Extended Reality in education.

- Have actively participated in research projects related to the use of Emerging Technologies or Extended Reality in the educational context.

3.4. Data Collection Procedure

3.5. Data Analysis Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Opportunities

“A clear change is perceived after the use of Virtual Reality in school subjects, mainly because they are enthusiastic about using the technologies because they find them innovative. It motivates them and they like to use it” (INTERVIEW.22)

“I observed that after applying this technology in my subject, the students understood and acquired the concepts and content much better, and it was reflected in the exams. I think it is quite significant in the process of teaching students” (INTERVIEW.08)

“The use of XR in school subjects has generated a clear change in the dynamics of collaborative work among students. It has been shown that the use of these technologies encourages greater interaction between students, creating an environment conducive to collaboration and mutual learning” (INTERVIEW.19)

“The adaptability of these technologies allows content to be tailored to the individual needs of learners, facilitating a more focused approach to their learning preferences and styles” (INTERVIEW.31)

4.2. Obstacles

“In my experience, many of us have not received adequate training on how to integrate Extended Reality into our classrooms. We don’t know how to use the tools, and this creates a barrier to implementing the technology effectively.” (INTERVIEW.12)

“Not understanding how to use Extended Reality is a barrier to designing meaningful educational activities. And therefore, we cannot take advantage of the full potential that this technology could offer our students”. (INTERVIEW.33)

“In our school, we have had difficulties in accessing the necessary technological resources to incorporate Extended Reality. The main barrier has been economic constraints, which prevent us from investing in specialised devices and equipment. In addition, the infrastructure of our classrooms is not prepared to handle these technologies either, which makes it difficult to use them”. (INTERVIEW.31)

“Mainly there are not enough resources in the classroom to apply these technologies. That is why we try to use low-cost tools like Merge Cube, which does not need many resources to be applied in classrooms” (INTERVIEW.04)

“I have a lot of difficulties in using the XR due to technical problems or outdated devices”. (INTERVIEW.38)

4.3. Future Prospects

“I believe that changes are needed at the political and educational level to overcome these obstacles. For example, it would be necessary to adapt the existing curricular contents and incorporate Extended Reality experiences in a coherent way and aligned with the pedagogical objectives”. (INTERVIEW.26)

“We currently have a big problem with the funding available to the school, as it limits us a lot when it comes to applying new methodologies that require electronic devices. Therefore, more funding would be a key element in solving this problem” (INTERVIEW.22)

“Raising teachers’ awareness of continuous training for future educational practices with the use of technology is the key element to bring about a significant change in this process. Also, a greater development and accessibility of such training”. (INTERVIEW.05)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Participants | Speciality | University | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expert 1 | Educational Technology | University of Seville | Professor |

| Expert 2 | Educational Technology | University of Granada | Professor |

| Expert 3 | e-Learning | University of Seville | Professor |

| Expert 4 | Educational Technology | University of Pablo de Olavide | Professor |

| Expert 5 | Gamification | University of Pablo de Olavide | Professor |

| Expert 6 | Virtual/Augmented Reality | University of Seville | Professor |

| Expert 7 | Distance Education | University of Córdoba | Professor |

| Expert 8 | Artificial Intelligence in Education | University of Huelva | Professor |

| Expert 9 | Educational Technology | University of Málaga | Professor |

| Expert 10 | Educative innovation | University of Granada | Professor |

| Expert 11 | Virtual/Augmented Reality | University of Huelva | Professor |

| Expert 12 | Educational Technology | University of Málaga | Professor |

| Expert 13 | Educational Technology | University of Almería | Professor |

| Expert 14 | Technology and gamification | University of Almería | Professor |

Appendix B

| Questions | Expert Response 1 | Expert Response 2 | … |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think that the questions addressed in the script are relevant for evaluating the application of Educational Technology? | Yes, the questions are relevant and cover key issues. | Some questions might be more specific to my area of expertise. | ... |

| What suggestions do you have for improving or adding additional questions to the script? | A question on the respondent’s previous experience with specific technologies could be included. | I propose to add a question related to the expectations of applying this tool in the future. | ... |

References

- Granados Romero, J.F.; Vargas Pérez, C.V.; Vargas Pérez, R.A. La formación de profesionales competentes e innovadores mediante el uso de metodologías activas. Rev. Univ. Soc. 2020, 12, 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Cukurova, M.; Luckin, R. Measuring the impact of emerging technologies in education: A pragmatic approach. In Second Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education; Voogt, J., Knezek, G., Christensen, R., Lai, K.W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Margrett, J.A.; Ouverson, K.M.; Gilbert, S.B.; Phillips, L.A.; Charness, N. Older adults’ use of extended reality: A systematic review. Front. Virtual Real. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, J. Teaching and Learning with Extended Reality Technology. In Proceedings of the BOBCATSSS 2019 Conference, Osijek, Croatia, 22–24 January 2019; pp. 138–146. [Google Scholar]

- Meirieu, P. El futuro de la Pedagogía. Teoría de la Educación. Rev. Interuniv. 2022, 34, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Liedtke, J.T.; Baraas, R. The Future of eXtended Reality in Primary and Secondary Education. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 2, 549–556. [Google Scholar]

- Doolani, S.; Wessels, C.; Kanal, V.; Sevastopoulos, C.; Jaiswal, A.; Nambiappan, H.R.; Nambiappan, F. A Review of Extended Reality (XR) Technologies for Manufacturing Training. Technologies 2020, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çöltekin, A.; Lochhead, I.; Madden, M.; Christophe, S.; Devaux, A.; Pettit, C.; Lock, O.; Shukla, S.; Herman, L.; Stachoň, Z.; et al. Extended reality in spatial sciences: A review of research challenges and future directions. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, P.; Kishino, F. A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 1994, E77–D, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, P.; Takemura, H.; Utsumi, A.; Kishino, F. Augmented reality: A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum. In Telemanipulator and Telepresence Technologies; Das, H., Ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, UK, 1995; Volume 2351, pp. 282–292. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, K. The integration of extended reality for student-developed games to support cross-curricular learning. Front. Virtual Real. 2022, 3, 888689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacca, J.; Baldiris, S.; Fabregat, R.; Graf, S.; Kinshuk, G. Augmented reality trends in education: A systematic review of research and applications. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2014, 17, 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Di Natale, A.F.; Repetto, C.; Riva, G.; Villani, D. Immersive virtual reality in K-12 and higher education: A 10-year systematic review of empirical research. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 2006–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radianti, J.; Majchrzak, T.A.; Fromm, J.; Wohlgenannt, I. A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Comput. Educ. 2020, 147, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleto, V.; Stanescu, M.; Rankovic MSevic, N.P.; Paun, D.; Teodorescu, S. Extended reality in higher education, a responsible innovation approach for generation y and generation Z. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Bhagat, K.K.; Yuan, G.; Chang, T.W.; Huang, R. The potentials and trends of Virtual Reality in education. In Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Realities in Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Meccawy, M. Teachers’ prospective attitudes towards the adoption of extended reality technologies in the classroom: Interests and concerns. Smart Learn. Environ. 2023, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Batanero, J.M.; Montenegro Rueda, M.; Fernández Cerero, J.; García Martínez, I. Digital competences for teacher professional development. Systematic review. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 40, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Fernández-Batanero, J.M. Adaptation and validation of an instrument for assessing the digital competence of special education teachers. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2023, 1–17. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08856257.2023.2216573 (accessed on 3 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Redondo, E.; Fonseca, D.; Navarro, I.; Villagrasa, S.; Peredo, A. Educational Qualitative Assessment of Augmented Reality Models and Digital Sketching applied to Urban Planning. A: Technological Ecosystem for Enhancing Multiculturality. In Proceedings of the TEEM’14 Second International Conference on Technological Ecosystem for Enhancing Multiculturality, Salamanca, Spain, 1–3 October 2014; Association for Computing Machinery. ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 447–454. [Google Scholar]

- Prendes, C. Realidad Aumentada y Educación: Análisis De Experiencias Prácticas Augmented Reality and Education: Analysis of Practical Experiencies. Pixel-Bit. Rev. Medios Educ. 2015, 46, 1133–8482. [Google Scholar]

- Urquiza Mendoza, L.I.; Auria Burgos, B.A.; Daza Suárez, S.K.; Carriel Paredes, F.R.; Navarrete Ortega, R.I. Uso de la realidad virtual en la educación del future en centros educativos del Ecuador. J. Sci. Res. 2016, 1, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dunleavy, M.; Dede, C.; Mitchell, R. Affordances and limitations of immersive participatory augmented reality simulations for teaching and learning. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2009, 18, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero Almenara, J.; Barroso Osuna, J.M. Posibilidades educativas de la Realidad Aumentada. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2016, 5, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Gayou, J.L. Cómo Hacer Investigación Cualitativa. Fundamentos y Metodología; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Batanero, J.M.; Tadeu, P.; Cabero Almenara, J. ICT and disabilities. Construction of a diagnostic instrument in Spain. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2018, 9, 332–350. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Cepena, M.C.; Cruz Ramírez, M.; Nápoles Valdés, J.E. Problemas de validez y métodos de experto en investigaciones de la educación especial. (Original). Roca. Rev. Científico-Educ. Prov. Granma 2021, 17, 527–547. [Google Scholar]

- WMA. World medical association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Area, M.; Cepeda, O.; Feliciano, L. Perspectivas de los alumnos de Educación Primaria y Secundaria sobre el uso escolar de las TIC. Rev. Educ. Siglo XXI 2018, 36, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores-Valencia, A.; De-Casas-Moreno, P. El uso de las TIC como herramienta de motivación para alumnos de enseñanza secundaria obligatoria estudio de caso Español. Hamut´ay 2019, 6, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos Soto, N.; Ramos Navas-Parejo, M.; Moreno Guerrero, A.J. Realidad virtual y motivación en el contexto educativo: Estudio bibliométrico de los últimos veinte años de Scopus. Alteridad 2019, 15, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre Cantero, J. Aplicación de Tecnologías Gráficas Avanzadas como Elemento de apoyo en los Procesos de Enseñanza/Aprendizaje del Dibujo, Diseño y Artes Plásticas. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- López-Rupérez, F. El currículo y la educación en el siglo XXI. In La Preparación del Futuro y el Enfoque por Competencias; Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- NEPT. Reimagining the Role of Technology in Education; U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://tech.ed.gov (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Herrada, R.I.; Baños, R. Aprendizaje cooperativo a través de las nuevas tecnologías: Una revisión. @Tic Rev. D’innovació Educ. 2018, 20, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro, P.P.; Luque, B.; Reina, A.; García-Peinazo, D.; Ojeda, D.; De la Mata, C.; Calderón-Santiago, M.; Gutiérrez-Rubio, D.; Antolí, A. Desarrollo de metodologías de aprendizaje cooperativo a través de Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación (TIC). Rev. Innovación Buenas Prácticas Docentes 2020, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso-Osuna, J.; Gutiérrez-Castillo, J.J.; Llorente-Cejudo, M.C.; Valencia-Ortiz, R. Dificultades para la incorporación de la realidad aumentada en la enseñanza universitaria: Visiones de los expertos. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2019, 8, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinghurst, M.; Duenser, A. Augmented reality in the classroom. Computer 2012, 45, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, M.; Howe, C.; McCredie, N.; Robinson, A.; Grover, D. Augmented reality in education-cases, places and potentials. Educ. Media Int. 2014, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P.; Treves, A.; Shmis, T.; Ambasz, D. The Impact of School Infrastructure on Learning: A Synthesis of the Evidence; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Delavande, A.; Zafar, B. Elección universitaria: El papel de los ingresos esperados, los resultados no pecuniarios y las restricciones financieras. Rev. Econ. Política 2019, 127, 2343–2393. [Google Scholar]

- Otero Franco, A.; Flores González, J. Realidad Virtual: Un Medio De Comunicación De Contenidos. Aplicación Como Herramienta Educativa Y Factores De Diseño E Implantación En Museos Y Espacios Público. Rev. Científica De Comun. Y Tecnol. Emerg. 2011, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Díaz, V.; Sampedro-Requena, B.E. La realidad aumentada en Educación Primaria desde la visión de los estudiantes. Rev. Educ. 2020, 15, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, M. Augmented Virtual Reality: How to Improve Education Systems. High. Learn. Res. Commun. 2017, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. The Development of Extended Reality in Education: Inspiration from the Research Literature. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, A.; Pagano, A.; Ladisa, L. Towards a mobile augmented reality prototype for corporate training. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on e-Learning, Porto, Portugal, 26–27 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, S.; Delgado, L.; Gimeno, M.Á.; Martín, T.; Almaraz, F.; Ruiz, C. The Educational Sandbox: Augmented Reality a new resource for teaching. EDMETIC Rev. Educ. Mediática TIC 2017, 6, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhurree, V. Technology integration in education in developing countries: Guidelines to policy makers. Int. Educ. J. 2005, 6, 467–483. [Google Scholar]

| Number of Participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | N | 20 |

| % | 55.5 | ||

| Women | N | 16 | |

| % | 44.5 | ||

| Age | Less than 30 years | N | 5 |

| % | 13.89 | ||

| Between 30 and 40 years | N | 18 | |

| % | 50 | ||

| Between 40 and 50 years | N | 8 | |

| % | 22.22 | ||

| More than 50 years | N | 5 | |

| % | 13.89 | ||

| Ownership of the centre | Public | N | 12 |

| % | 33.3 | ||

| Concerted | N | 15 | |

| % | 41.6 | ||

| Private | N | 9 | |

| % | 25 | ||

| Teaching experience | Between 0 and 5 years | N | 10 |

| % | 27.78 | ||

| Between 5 and 15 years | N | 22 | |

| % | 61.11 | ||

| More than 10 years | N | 4 | |

| % | 11.11 | ||

| Q | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | Demographic questions: gender, age, school ownership |

| 2 | How would you describe your initial experience of introducing Extended Reality in the Primary School classroom? |

| 3 | What have been the main challenges you have faced when introducing Extended Reality into the classroom? |

| 4 | What, in your experience, are the most significant opportunities that Extended Reality provides in the teaching–learning process in Primary Education? |

| 5 | From your teaching perspective, what changes or developments do you expect to see in the use of Extended Reality in the coming years? |

| 6 | How could the preparation of teachers to effectively integrate this technology in the classroom be improved? |

| 7 | Finally, is there anything else you would like to add? |

| Categories | Subcategories | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Opportunity (OP) | Motivation (M) | “Whenever technology is used, students are motivated, and this has a positive impact on their learning” (INTERVIEW.06) |

| Academic Performance (AP) | “The use of ICTs improves academic performance, because it is innovative, and students like it and are enthusiastic about it” (INTERVIEW.29) | |

| Personalisation of Learning (PL) | “The existence of enhanced personalisation of learning according to the characteristics of the learner makes Extended Reality incredible” (INTERVIEW.02) | |

| Co-operative Work (CW) | “To a greater extent, group work helps the teaching and learning process of students” (INTERVIEW.23) | |

| Obstacles (OB) | Teachers Training (TT) | “The teacher has the opportunity to do some training on the technology, but it is not usually specific to Extended Reality” (INTERVIEW.20) |

| Availability of Resources (AR) | “There is a shortage of resources to use for all pupils in the school at the same time” (INTERVIEW.01) | |

| Financial Cost (FC) | “Many centres do not have the money to use these tools unfortunately” (INTERVIEW.15) | |

| Infrastructure (I) | “The internet connection has been one of the worst problems we have had during the academic year” (INTERVIEW.32) | |

| Future Prospects (FP) | Education policy (EP) | “A restructuring of education policies would be necessary to improve both their use and student learning” (INTERVIEW.17) |

| Lifelong Learning (LL) | “Continuous training, there should be more facilities” (INTERVIEW.29) | |

| Funding (F) | “That schools allocate more funding to the acquisition of such resources” (INTERVIEW.10) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Batanero, J.M.; Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Fernández-Cerero, J.; López-Meneses, E. Extended Reality as an Educational Resource in the Primary School Classroom: An Interview of Drawbacks and Opportunities. Computers 2024, 13, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers13020050

Fernández-Batanero JM, Montenegro-Rueda M, Fernández-Cerero J, López-Meneses E. Extended Reality as an Educational Resource in the Primary School Classroom: An Interview of Drawbacks and Opportunities. Computers. 2024; 13(2):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers13020050

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Batanero, José María, Marta Montenegro-Rueda, José Fernández-Cerero, and Eloy López-Meneses. 2024. "Extended Reality as an Educational Resource in the Primary School Classroom: An Interview of Drawbacks and Opportunities" Computers 13, no. 2: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers13020050

APA StyleFernández-Batanero, J. M., Montenegro-Rueda, M., Fernández-Cerero, J., & López-Meneses, E. (2024). Extended Reality as an Educational Resource in the Primary School Classroom: An Interview of Drawbacks and Opportunities. Computers, 13(2), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers13020050