Abstract

According to a study by the German Federal Printing Office (2022), every European lives with 90 digital identities on average, and the trend is rising. The German government has launched the innovation competition “Digital Identities Showcase” to select and promote identity projects for data security and sovereignty. The funding amount is 50 million EUR to develop software, research practical use cases and implement them by 2024. Of course, this large sum presupposes acceptance for the use of such digital identities, especially against the backdrop of critical opinions from the media and society, as already outlined in a Canadian study. However, there is little academic research on blockchain technology, but almost no article on the use of digital identities based on blockchain technology. This paper conducts a quantitative study on the social acceptance of digital identities using a questionnaire-based survey with 324 German participants on the social acceptance of the use of digital identities. The result of the study is that social acceptance of the use of digital identities is significantly influenced by demographics, citizens’ experience with blockchain products, affinity with financial products and privacy concerns.

1. Introduction

Despite a great progress in digitisation, individuals still possess many different analogue proofs of their own identity which tend to be unsafe and difficult to overlook. The vision of digitising identities has brought forth various innovations. One innovation refers to the distributed ledger technology (DLT) and the concept of self-determined identity, which has experienced attention in recent years. This development is referred to as “Self-Sovereign Identity” (SSI). DLT is associated with the term of blockchain. A blockchain is a data bank, which is distributed within a decentralised network. Each participant in this network possesses a copy of the data bank with its information about transactions, thereby increasing tamper security. If one data bank is being hacked, there are many more data banks which communicate with each other to decide about the legitimacy of a transaction. This is one of the major benefits from DLT and blockchain-based innovations. SSI intends to use this specific characteristic to provide data security and foster the digitisation of processes, which include the authentication and verification of identities.

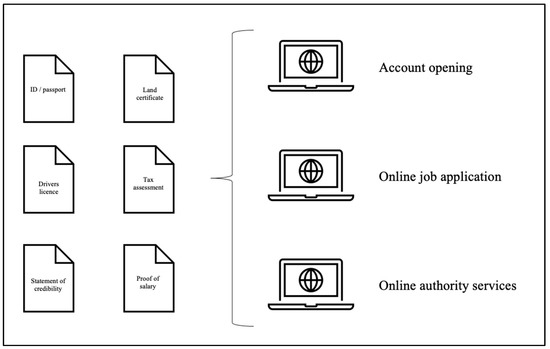

In the context of identity, the literature often refers to the authenticity of a person or the complete alignment with what an individual is. Ref. [1] defined digital identity as the electronic representation of personal information of an individual or an organisation (e.g., name, address, contact data, social profiles, etc.). A classic example of this is the physical identity card or passport, which proves an individual’s personal identity characteristics (e.g., date of birth, eye colour, height). However, the concept of identity encompasses more than the mere proof of the classic ID card. Driver licenses, health cards, employer ID cards, credit cards or membership cards are examples to mention (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Different digital identities and proofs for different online services.

Other proofs of identity, which are more likely to be found in analogue files are birth certificates, university certificates, marriage certificates, or extracts from land registers with proof of ownership. The identities and proofs listed are typical of the era before the Internet. However, with the use of the internet, additional electronic identities in the form of online accounts were added, where citizens authenticate themselves using usernames and passwords. According to a recent study by the German Federal Press, every European has on average “over 90 digital identities, and the trend is rising” [2]. The results underline the challenge mentioned at the beginning of keeping track of one’s own identities together with the corresponding evidence.

For the reasons mentioned, the digitisation of analogue proof of identities not only creates administrative simplifications for citizens but also paves the way for the private and public sectors to offer fully digitalised services. Since the major obstacle to digitisation in Germany is the lack of easy-to-use digital identities and proof. Therefore, the blockchain strategy of the Federal Government contains-in addition to many other important innovation topics—a chapter on digitising administrative services [3]. With the declared innovation competition “Schaufenster Digitale Identitäten”, which is organised by the German government, selected identity projects for data security and sovereignty were funded. A total of four showcase projects are currently being funded with a total of 50 million EUR to develop software, research practical use cases and finally implement them by 2024. All projects follow the same goal of developing user-friendly solutions to foster the use of blockchain-based identities and their proofs.

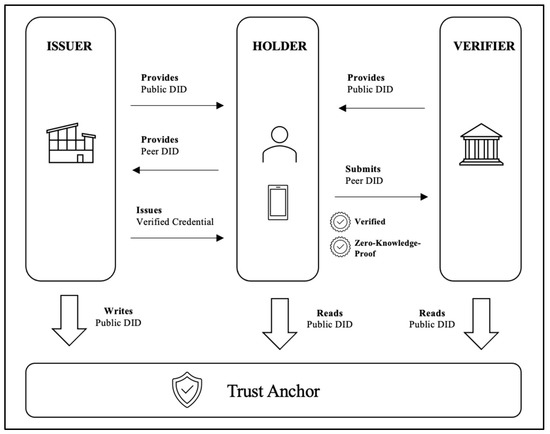

Figure 2 illustrates an overview of the function when using SSI-technology for online services. In the following, the processes are shortly described to explain the idea behind the use case for private persons. The example with its basic idea is based on the practical implementation of a German SSI-project and depicts one of many possible ways of SSI. In the given case, the issuer can be any company, authority, or institution which issues identities or proofs of identities. When using a blockchain-based solution, the issuer will issue a decentralised identifier (DID). DIDs are used to make a reference to any subject as determined by the controller of the DID. DIDs can be regarded as a modern type of identifier that can be used as a verifiable and decentralised digital identity, thereby enabling SSI-solutions. In this example, these DIDs are available in the blockchain, which can be read by any participant within this SSI ecosystem to verify the authenticity of an identity and its digital proof. Generally, DIDs are not necessarily hosted in the blockchain and may have different appearances due to the given context or project implementation.

Figure 2.

Different digital identities and proofs for different online services.

The DIDs are thus verified and based on zero knowledge-proof. Both mentioned features are key to why SSI offers modern opportunities in almost every field in life, which can be subject to digital services.

The objective of this article is to research the acceptance of private users to use identity management solutions, which are based on blockchain. This implies the question about the general usage of wallet-applications, which can store personal identity data on mobile devices. This paper provides specific use cases to assess the relevance of SSI and address the main question about the probability to use SSI-wallets. Therefore, we asked private users of their usage situation of and their experience with wallet-applications. Our survey was answered between October 2021 and April 2022, by a total of 324 people. It aims to explore the behaviours of respondents with different demographic, financial and knowledge backgrounds towards the use of digital wallet apps. For this purpose, 26 questions have been designed, from which four defined models have been set up to provide information about their behaviour. To elicit these behaviours, each model has the nominally scaled (dichotomous) dependent variable as the question of whether the respondent has used or would use digital wallet apps, the response and likelihood of which is explained by our models. The explanatory 25 variables consist of 10 nominally scaled (dichotomous) dummy variables, 6 ordinally scaled variables whose response interpretation comes from a Likert scale, and 9 metric-interval scaled variables. Due to this survey design, we use a Qualitative and Limited Dependent Variable Model for our study. Table 1 shows the response distribution of the respondents.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents.

We conducted a literature analysis and find that social acceptance of the use of digital identities is significantly influenced by demographics, citizens’ experience with blockchain products, affinity with financial products and privacy concerns. Table 2 lists a summary of our results from all regression models where the p-values of the certain variables within the models show significant results:

Table 2.

Result overview of models.

The interpretation “−“ means the variable value increases at one level, the probability to use digital identities in wallet apps decreases at the value shown by the coefficient and “+” means the variable value increases at one level, the probability to use digital identities in wallet apps increases at the value shown by the coefficient. Our result interpretations imply for wallet app providers that they should sufficiently educate especially the older generation of citizens regarding data protection and ensure a comfortable use of their products. The related education level of citizens shows that the likelihood of knowledge and awareness of blockchain increases the willingness to use it. This is because the experience gained in using these wallet apps does not necessarily lead to the conclusion that they will be used again and again.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we provide an overview of the current state of research, as we find that there is a large gap in research articles, although this topic in general has a high potential for discussion. Based on the collected literature, we formulate the hypotheses for our study. In Section 3 we describe the basic methodology and specify our research model. Section 4 shows the survey and data sample we use for our study. It also describes the descriptive statistics and presents them graphically. In Section 5, the empirical investigation with its results is conducted using the research method. At the end of our investigation, the results are critically reflected and the hypotheses formulated in Section 2 are answered. The results are summarised in Section 6.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

In preparation for our investigation and for the formulation of our hypotheses, we provide below an overview of the existing literature in the form of scientific articles, whereby the selection of the cited studies is based on the relevance and ranking of the journal and the order is sorted according to the directions of investigation. Articles from journals with medium and low impact factors were analysed, whose publication dates at the current time are close to the past. The reason for this is that digital identities have not existed for long and are used by private individuals. For this reason, the scientific literature has not yet paid much attention to the social acceptance of digital identity consumers. Journals with a high impact factor do not offer any studies on this topic so far. In this regard, Google Scholar, as well as Mendeley’s search, have been analysed for different keywords, leading to few results so far. The focus of all relevant publications including the Internet offering is increasingly concentrated on the functionalities and the various areas of application of identity management systems (IdMS) from which consumers experience a benefit.

Based on the survey methodology of [4,5], the study extended the body of research by examining data privacy concerns, as well as privacy concerns of Internet users. They identified multidimensional privacy concerns related to IdMS and aim to understand and explore their impact on users’ behavioural intentions when adopting IdMS. Ref. [6] addressed these systems in general and discuss the benefits conferred to the private user that aggregate complex and fragmented user information. They show that current federated systems do meet user needs by allowing the construction of multiple digital records linked to a central identifier. However, they do not give the user control over the ability to act in the “hatching”, “matching”, and “sending” phases of the digital identity lifecycle. Ultimately, this reduces user trust in providers and leads to a reluctance to disclose personal information. This result provides the basis for our investigation, where our interest lies particularly in the developmental change in user thinking. Ref. [7] also addressed beneficial digital identities in the context of identity documents, as new technologies increasingly enable identity verification and identification of individuals in the digital age. Digital identity technologies can make undocumented individuals more visible and thus less vulnerable to abuse and exploitation.

In addition to IdMS, there are other authentication systems, such as electronic identification systems (eIDAS, in short: eID), which are already regulated by the EU. Ref. [8] contributed to the discussion on pseudonyms and multiple identities by providing an original analytical framework that can be used to assess privacy in any eID architecture. They also elaborated the concept of the eID implementer, which can be used to model virtually any case of the relationship between the user, the eID implementation, and the user’s digital identities. Based on these inputs, they performed a comparative analysis of four exemplary eID architectures deployed in European countries. They also discuss how sensitive citizens in these countries are to the privacy argument when adopting these systems, finding that there is no evidence of a significant impact of privacy-friendly features on eIDMS adoption in four European countries. They also find that significant structural differences in privacy protection may influence users’ willingness to adopt better solutions in daily use. Ref. [9] followed this up by discussing the long-term success of usage after implementing such eIDAS architectures, focusing (just as we do) on social acceptance. They outline the challenges of creating a European interoperability solution that enables convergence with the development of national eID strategies and meets the values of all stakeholders.

The repeatedly discussed privacy concerns regarding the privacy of private individuals can potentially be improved or even eliminated by the blockchain-supported integrity of identity management systems, which we assume will increase the social acceptance of such systems. Ref. [10]’s research drew on his own experiences with an ecosystem approach to digital identity. In doing so, he discusses the potential value of using blockchain technology to address current and future identity verification and authentication challenges in the Canadian context and [11] for China. He concludes, first, that leaders can contribute to the digital ecosystem by creating an open and collaborative culture where knowledge and innovation are shared with the industry for the public benefit, and second, by setting quality and communication standards. They can also contribute by remaining open to change and embracing digital adoption and transformation of their management models and infrastructures. In addition, SecureKey technologies’ vision of its solution is shaping the future of digital identities and redefining the way consumers and businesses approach identity verification and the exchange of important personal information. Building on SecureKey technology, [12] introduced public-key infrastructure. In the context of blockchain, it can help realise a sovereign identity that gives users control over their information by enabling decentralised handling of public key infrastructure. In their paper, they also present the Sora identity system, which is a mobile app that uses blockchain technology to create a secure protocol for storing encrypted personal data as well as exchanging verifiable details about personal data. Their system uses mobile apps that allow users to interact with the approved blockchain Hyperledger Iroha to digitally sign and share proofs of their personal information.

The protection of personal information for evaluation purposes of large cloud computing providers is represented by the so-called CloudAgora mechanism, whose most important element is blockchain technology. Ref. [13] presented this platform as a prototype that allows any potential resource provider-from individuals to large enterprises-to competitively market unused resources on equal terms and enables any cloud customer to access low-cost storage and computation without having to trust a central authority. Further, cloud users can request storage or compute resources, upload data, and outsource processing of tasks across remote, fully distributed infrastructures. They are the first whose prototype as Dapp is built on Ethereum and available as an open-source project.

Blockchain technology, through immutability and transparency, particularly improves various e-government services, which have evolved significantly since the last decade, according to [14]. In their paper, they identified which e-government services can benefit from the use of blockchains, the types of technologies chosen for the proposed solutions, and their maturity level. To do this, they conduct a systematic literature review of 19 academic articles and find that Authentication, Data Sharing, e-Voting, Land Property Services, e-Delivery Services, HR Management, and Government Contracting are significantly improved using blockchain technology. Its innovation comes from the combination of transparency, integrity, confidentiality, and accountability when properly designed. In addition, a distributed blockchain network strengthens trust between all stakeholders, as transactions are conducted securely and without the approval of a central authority. Ref. [15] explored how blockchain technology and the Internet of Things interact to better understand how devices can communicate with each other. The blockchain-enabled Internet of Things architecture proposed in this paper is a useful framework for integrating blockchain technology and the Internet of Things using the most advanced tools and methods currently available. Ref. [16] highlighted the numerous innovation opportunities that arise from combining Blockchain technology with the Internet of Things (IoT) and Si-security frameworks. The deployment and use of IoT device networks in smart city environments has generated an enormous amount of data. An innovative and open IoT blockchain market for applications, data and services is proposed that (i) provides the framework on which objects and people can exchange value in the form of virtual currencies for received assets (data and services) and (ii) defines the motivational incentives according to social and business contexts for interaction between people and smart objects.

Ref. [17] explored how the Internet of Things and blockchain technology can benefit sharing economy applications. The focus of this research is on how blockchain can be used to create decentralised sharing economy applications that allow people to securely monetise their things to create more wealth. Examples of such distributed applications in the context of an Internet of Things architecture using blockchain technology. Ref. [18] showed how blockchain can be adapted to the specific requirements of IoT to develop blockchain-based IoT (BIoT) applications. Such a vision requires seamless authentication, privacy, security, robustness against attacks, ease of deployment, and self-maintenance, among others. Such features can be provided by blockchain, a technology that emerged with the cryptocurrency Bitcoin. Although there are some studies on the security and privacy of blockchain, there is a lack of systematic research on the security of blockchain systems. Ref. [19] conduct a systematic study of security threats to blockchain using some of the most popular blockchain systems (e.g., Ethereum, Bitcoin, Monero, etc.) and enumerate the relevant real-world attack cases. They summarise solutions to improve the security of Blockchain, which provide guidance for the healthy development of Blockchain. According to [20], Blockchain is the technology underlying Bitcoins, and it provides a decentralised framework to validate transactions and ensure that they cannot be altered. By distributing the role of information validation to the peers of the network, Blockchain eliminates the risks associated with a centralised architecture. It is the most secure and efficient validation mechanism that enables the delivery of financial services and gives users more freedom and power. They provide a holistic overview of various applications of CPS where blockchain has been used. Smart power grids, healthcare systems, and industrial manufacturing processes are just a few of the many applications that can benefit from blockchain technology discussed in their paper.

Ref. [21] conducted a systematic literature review to present the adoption frameworks most used to evaluate blockchain adoption and identify in which business sectors these models have been applied. To do this, they examine blockchain adoption models in 56 articles and summarise the results of the studies by categorising the articles into five main areas, including supply chains, industries, financial sector, cryptocurrencies, and other articles (excluding the former areas). The results of their study showed that the models based on the technology acceptance model (TAM), technology organisation environment (TOE), and new conceptual frameworks were the focus of the majority of the selected articles. Most of the articles focused on the adoption of blockchain in various industries and supply chain sectors.

Ref. [22] also showed the benefits associated with digital identity systems but also addressed the associated risks in terms of privacy. Considering the significant impact of these systems on private users, it is necessary to have an evaluation framework that could help understand the suitability of a DIS in each context. In their study, they proposed a conceptual evaluation framework based on the processes followed, regulations and technologies used.

In preparation for our study on the social acceptance of digital identities, [23,24] formed the basis for the acceptance of digital surveillance in the age of Big Data. Ref. [23] addressed the security and acceptance of digital identities in their research, cautioning that birth certificates, for example, are often forged or misused due to a lack of security features, allowing legitimate identity documents to be obtained under false pretences. They show how identity documents can be improved without compromising social acceptance of the technology by collecting survey data from nine countries. Their (preliminary) findings suggested that the security of birth certificates needs to be improved, for example, using biometric security features. Another possible solution is to issue identity cards from birth instead of issuing a birth certificate. They examined citizens’ concerns about their digital identities, nation-state intelligence activities, and the security of personal data, and address their impact on trust in and acceptance of government use of personal data. Their data are based on survey documentation in [25,26,27].

Ref. [24] surveyed 1486 Canadians and find that their concerns have a negative impact onto citizens’ acceptance of government use of personal data, but not necessarily on their trust in the nation state’s respect for privacy. Government and businesses, they conclude, should be more transparent in their collection and use of data, and citizens should more actively “watch the watchers” in the age of Big Data. In our study, we address two of their proposed future research themes. Following [22], people in different countries view surveillance differently due to cultural, political, and social elements. Therefore, in line with the ideas of [28,29], future research should investigate public opinion on digital surveillance not only in one country but also in other countries, regions, and cultural environments. Our research is based on the responses of 324 German residents who are growing up in this Big Data era and are more engaged with digital identities compared to other age groups. Furthermore, based on our questions, we can draw conclusions about demographic groups, such as age, gender, and education level, which also opens a potential research question according to [24].

Based on the existing literature findings, described research limitations and research gaps, we pose the following hypotheses in preparation for our study:

H1.

Different demographic groups increase the likelihood of using digital identities in wallet apps.

H2.

Individuals’ experience with blockchain products increases the likelihood of using digital identities in wallet apps.

H3.

Individuals’ affinity for financial products increases the likelihood of using digital identities in wallet apps.

H4.

Privacy concerns increase the likelihood of using digital identities in wallet apps.

For the first hypothesis, we address the future research themes proposed by [24] by making demographic group classifications. We further aim to find out whether private users’ experiences with blockchain products, their affinity with financial products, and the privacy concerns often discussed in the literature influence the social acceptance of digital identity use. In doing so, we contribute significantly to scientific knowledge gains and close a research gap in the field of digital transformation with our context analysis and its results.

3. Qualitative and Limited Model of the Dependent Variable

In this Section we describe the model we use because of the characteristics and objective of our survey. This is the Limited Dependent Variable Model, which we describe theoretically below and specify for our research hypotheses.

3.1. Model Theoretical Description

The theoretical framework of our study is based on a Qualitative and Limited Dependent Variable Model, which is an application of the multiple regression model to a binary dependent variable whose value range is strongly restricted by the values zero and one (as a dummy variable). We use this model because in each of the five specifications a dependent variable takes on values between zero and one (no and yes) due to the question and the respondent’s answer in the survey. For this reason, we limit the model by ensuring that the response probability will not be above or below 100% or 0% (yes or no). Thus, we define our response probability as

where P is the response probability from the explanatory variables x1, x2,…, xn summarised as x and the alternatives in the cases

are taken into account. We express these linear response options of our respondents for each case as

which means that the probability of the possibility “yes” is a linear function of is. is also the answer probability with the possibilities of the function G of all possibilities z between 0 and 1. represents the constant and are the coefficients of the explanatory variables whose sign shows the effect on the response effect of the dependent variable.

P(y = 1∣x) = P(y = 1∣x1, x2, …, xn),

In our modelling, we use logistic regression for the reason of the limited possibilities of G, which we express with the probabilities and the cumulative distribution function in the standard logistic model as

Since our model consists of a binary dependent as well as binary and discrete explanatory variables, the model has to be modified according to G and x

with all values of and for the case that is a dummy variable. For the case of a discrete variable we use, starting from the difference of G and the effect on the probability that to is

Based on our survey, we use the standard specification of linear logistic regression to estimate the probability of the dependent variable for all five models with the form

where . The error terms are independent and identically Gumbel distributed. Since has only two possible outcomes (0 or 1), the error term for a given value of also has two possible outcomes. In particular, the distribution of can be summarised as follows:

This means that the variance of the error term is not constant but depends on the explanatory variables according to .

To estimate the model, we use the maximum likelihood method, since here the distribution of y is based on the dependence on x, in which heteroscedasticity is automatically taken into account. Furthermore, we imply the general theory of random sampling so that the maximum likelihood estimation is consistent, asymptotically normal and asymptotically efficient.

Interpreting the coefficients of the regression outcome, the signs of the partial effects of each x on the probability of response, and the statistical significance of x is determined by whether we can reject the null hypothesis at a sufficiently low significance level. Since all of our four models estimate the probability of use of digital wallet apps, we consult Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) as a goodness-of-fit comparison because (1) it lends itself well to model comparisons, (2) it is less noisy because it does not include random components, and (3) it includes all probabilities. For each explanatory variable, we look at the p-value, which determines whether the regressor variable actually affects the dependent variable or not. Furthermore, we look at the success of predicting our models from the Actual Predicted table with 0 and 1 (no wallet app use vs. wallet app use).

3.2. Model Specifications

The previously established hypotheses are incorporated into the logistic regression format in the individual following Sections and linked to theoretical explanations on SSI, blockchain and digital wallets.

3.2.1. Demographic Differences

As stated by [28], demographic criteria also have an effect on the acceptance of using digital identities through wallet apps. We test this hypothesis and specify the following model based on the demographic information provided in the questionnaire:

whereby in this model we take into account both personal information through the explanatory variables:

- Gender: dummy variable with 1 = male and 0 = not male (female, diverse) ➞ With this, we would like to find out whether a gender-specific urge to use digital identities can be recognised.

- Age: Metric variable with age in years ➞ The question here is whether younger or older German citizens tend to use digital identities in wallet apps.

- Net income: Metric variable with monthly net salary in EUR ➞ Do higher-income citizens tend to use digital identities through wallet apps, who in connection with their salary may have several bank accounts and several customer memberships in the form of online accounts for shopping on the internet, for which they can register and log in more frequently (and more conveniently + quickly) with the providers? (See model 4)

- Academic background: The answers are given as a nominally scaled variable in the form of ascending educational level (no degree, intermediate school leaving certificate, (technical) school leaving certificate, vocational training, bachelor’s/diploma, state examination, master’s, doctorate, habilitation) and coded as a dummy variable in 1 = academic educational level and 0 = no academic educational level. ➞ In this way, we want to investigate the question of whether citizens with an academic educational background have a different understanding of the use of digital identities than citizens without an academic background.

- Employment situation: The answer to this question is given as a nominally scaled variable in the form of the employment relationship (job-seeking, part-time or full-time employed or self-employed/freelance) and is coded as a dummy variable in 1 = is in employment and 0 = is not in employment. ➞ We want to find out whether permanently employed citizens tend to use digital identities.

- Living in one’s own property: This variable is also originally based on a nominal scaling, which provides information about the current living situation of the respondents (own house, condominium, rented house, rented flat (incl. shared flat)). It is coded in a dummy variable and says 1 = living situation in own property and 0 = living situation as tenant. ➞ Can the resulting security in the form of ownership explain the use of digital identities?

As well as the family situation:

- Relationship: Originally nominally scaled variable (in committed relationship, married, single, widowed) and coded into a dummy variable with 1 = in committed relationship and married and 0 = living alone. ➞ The security triggered by this could also explain the likelihood of using digital identities.

- Number of children: This is a metrically scaled variable containing the number of children.

3.2.2. Private Individuals’ Experiences with Blockchain Products

In this hypothesis, we test two models. In the first model, we specify the experiences the respondents have had with the past use of blockchain products, and here we focus particularly on the blockchain reference. We specify the second model with the experiences divided into certain categories that the citizens have had with the digital products and have given corresponding answers in the questionnaire. We only include those citizens who have indicated in their answer that they have already used digital products with a blockchain connection.

The first model is based on three explanatory variables, which give the model the following structure:

where the explanatory variables are based on the following background:

- Ever heard of Blockchain: This variable is based on the question whether the respondent has ever heard of Blockchain and can be answered in its dichotomous form with 1 = Yes and 0 = No. ➞ We are investigating the question of whether citizens who have heard of blockchain are more inclined to adopt digital identities or vice versa. The background to this is that due to the simple design of digital identities in wallet apps, no knowledge of blockchain would need to be present. Many providers, such as Apple and Google, actively advertise easy-to-use and self-explanatory wallet apps that can be used by citizens.

- Blockchain functionality know-how: Here, the question is about how well the respondents assess their knowledge of blockchain functionality. The answers are presented with an ordinal-scaled variable with a Likert scale of 1 to 3 (1 = No, 2 = Partially, 3 = Yes), whereby we decide to code this variable into a dummy variable with 1 = Yes and 0 = No due to imprecision in the citizens’ own self-assessment. ➞ Could citizens who have good knowledge of blockchain functionality also be more inclined to use or not use digital identities managed in wallet apps. Their willingness to use depending on their knowledge is thereby guided by the idea of a decentralised order structure, as this has always functioned as a leitmotif of DLT. Centralised power structures or institutions could misuse identities, which would be conspicuous in a decentralised network structure. Experienced blockchain users are familiar with this advantage, for example, when carrying out transactions using payment tokens such as Bitcoin or Ether. The peer-to-peer (P2P) approach is particularly appreciated here, where central institutions such as banks lose out. With reference to digital identities, identities and their proofs can thus be transmitted directly from the user to a company, eliminating essential intermediate steps or verifying companies. Using the example of financing in a goods shop, the digital credit identity (if already successfully issued) can be shared directly from the customer to the shop. The intermediate step of querying the creditworthiness at Schufa thus becomes obsolete, which leads to a simplification of the customer journey in the example. A negative attitude towards wallet apps could exist if users do not believe in the decentralisation of a network and suspect risks in the blockchain protocol. This could also have a negative impact on the likelihood of using digital identities.

- Used blockchain products: Whether respondents have already used products with blockchain technology (e.g., crypto, staking, NFT investment) answers this variable, which is based on dichotomous coding with 1 = Yes and 0 = No. The aim here is to discuss the extent to which the likelihood of using digital identities depends on previous experience with blockchain products or services.

With the second model, we also want to find out whether those citizens who have already used blockchain-related products tend to use digital identities managed in wallet apps based on their experiences (divided into four categories). The underlying question is how they rate the benefit of such a wallet in terms of convenience/saving time/clarity. Here, only the answers in the independent variable “Use of blockchain products” are shown with the cases:

where we use only the “yes” answers, with the vector x = 1. We then specify the model with the four independent variables containing the experiences of the specific categories with:

All variables are ordinally scaled with a Likert scale and are described as follows:

- Convenience rating: This variable is based on the question of how the product’s usefulness is rated in terms of convenience, where 1 = no usefulness, 2 = less usefulness, 3 = moderate usefulness, 4 = high usefulness and 5 = very high usefulness (also for the following categories).

- Assessment of time saving: Assessment of time saving.

- Assessment of clarity: Assessment of clarity.

- Assessment of self-determination: Assessment of self-determination.

3.2.3. Affinity of Citizens to (Digital) Financial and ID Products

With this model, we want to find out whether and in what number citizens use digital financial and identification products. The majority of use cases to date in connection with blockchain and DLT relate to the financial services sector. Here, the talk is primarily of decentralised finance or DeFi, which stands for the offer of blockchain-based financial products and services. Accordingly, we assume a positive correlation between the number of financial products used, as these can be improved by means of DLT (e.g., faster transactions, lower costs).

With this in mind, we specify the following model for logistic regression with six explanatory variables, each indicating the number of products:

whose variables indicate the respective number of the following products and is therefore metrically scaled:

- Bank cards: Do citizens with higher numbers of bank cards tend to use digital identities? This includes, for example, debit and credit cards, which are typically used for digital and analogue payment transactions.

- Customer cards: How many loyalty cards do the respondents have with which online shopping is also possible? There are a variety of options here, ranging from classic loyalty cards for discounts to points cards from certain providers (e.g., Payback).

- Online accounts: How many online accounts do ISP respondents have and, if more, do they tend to manage digital identities in wallet apps for convenience, which store respondents’ data directly and thus help save time or reduce login procedures? This includes, for example, social media accounts, mail accounts and all other user accounts used in digital customer journeys.

- Identification documents: Identity documents are documents or proofs issued by an official authority. These include classic identity cards, birth certificates or driving licences. In Germany, for example, the German Federal Press issues a citizen’s official identity card.

- Testimonial documents: This includes documents such as the employer’s reference or other documents that contain an evaluative character about a person. These are not certified separately. Typically, assessments may be in the form of grades that can be used as evidence by the user.

- Certificate documents: Certificate documents are proofs such as the university degree certificate or proof of a specific further education or training course. These documents are characterised by the fact that they are certified by a specific organisation or entity.

3.2.4. Privacy Concerns

Following [23], we use this model to test the extent to which citizens’ privacy concerns influence the likelihood of using digital identities. This is relevant because the use of blockchain-based applications is still associated with general risks and feelings of uncertainty. This is due to the novelty of the technology and the critical reports in the media.

Based on this, we specify the model as follows:

where the independent variables are defined as follows:

- Importance of data security: This is an ordinal scaled variable based on the question of the importance of data protection, with Likert scale (1 = not thought about it yet, 2 = unimportant, 3 = moderately important, 4 = important and 5 = very important). ➞ We are thus pursuing the question in the literature as to whether German citizens are also oriented towards higher data protection when using digital identities.

- Trust in companies and governments: This ordinal scaled variable provides information on the question of how high the trust towards private companies and governments is with regard to the protection of the respondents’ personal data? Answers could be selected from the Likert scale with 1 = no trust, 2 = low trust, 3 = medium trust, 4 = high trust and 5 = very high trust. ➞ The main concern here is that data is not misused or kept secure. Could citizens whose trust in private companies and governments is very high also be more inclined to use digital identities?

- Assessment of data security at usage blockchain: This is originally an ordinal scaled variable that asks about the assessment of data protection in the event that blockchain technology is used. Answers could be 1 = Yes, 2 = Partially and 3 = No. We decided to code this variable dichotomously with 1 = “Yes” and “Partially” and 0 = “No”, as the respondents’ assessment could contain knowledge gaps and the discriminatory power between “Yes” and “Partially” is only partially given.

- Knowledge store data by companies: This is an ordinal scaled variable for the question, “How do you rate your own level of knowledge regarding what personal data of yours is stored by companies?”, where on a Likert scale of 1-5, with: 1 = not knowledgeable, 2 = less knowledgeable, 3 = medium knowledgeable, 4 = high knowledgeable and 5 = very knowledgeable. We thus address the question of whether citizens with very high knowledge of corporate data storage also tend to use digital identities.

4. Survey and Data

In this section, we describe the survey conducted and the resulting data sample used for our study with the Qualitative and Limited Dependent Variable Model. In order to use this methodology, the data must be subjected to a preliminary review to determine whether it is suitable for the study or whether it has certain statistical properties that could affect the estimation results. We also provide an overview of the descriptive statistics on the respondents’ answers.

4.1. Survey and Data Sample

The survey was conducted between October 2021 and April 2022 and went out to 853 respondents. It aims to explore the behaviours of respondents with different demographic, financial and knowledge backgrounds towards the use of digital wallet apps. For this purpose, 26 questions have been designed, from which 5 defined models have been set up to provide information about their behaviour. The questions can be answered with firmly defined answer options. The question whether the respondent has already used or would use digital wallet apps is the nominally scaled (dichotomous) dependent variable whose answer and probability are explained by our models. The explanatory 25 variables consist of 10 nominally scaled (dichotomous) dummy variables that take the values 1 and 0, 6 ordinally scaled variables whose response interpretation comes from a Likert scale, and 9 metric-interval scaled variables. Due to this survey design, we use a Qualitative and Limited Dependent Variable Model for our study.

Of the 853 respondents, a total of 345 answered, with 21 responses not being able to be included in the assessment due to missing or unusable information. This means that each of our response variables has a number of n = 324 observations. To determine the meaningful sample size based on a sufficient number of survey responses, we use [30] power estimation in the “G-Power 3.1” application. We want to estimate the sample size necessary to achieve a power of at least 0.95 in a two-tailed test with α = 0.05. To do this, we specify the input with , other , and a normal distribution with and . Thus, we obtain a critical z-size of 1.959 and a minimum sample size of 317, which leads to the desired test power of 0.95.

4.2. Pre-Check of the Data

Before we estimate the models, we check the data to ensure that they meet the requirements of logistic regression. The literature defines the following requirements:

(1) Our dependent variable is nominally scaled and dichotomously coded as a dummy variable.

(2) The observations are independent of each other, so there is no relationship between the observations in each category of dependent variables (predictors) or the observations in each category of nominal independent variables (criterion). Our observations are not from repeated measures or matched data. They are therefore independent of each other.

(3) The sample size must meet a certain test strength, and here we are guided by the explanations of [30]. In a multiple logistic regression model, the effect of a particular covariate is tested in the presence of other covariates. In this case, the null and alternative hypotheses are as follows:

Here, we denote by the probability of observing the response under which is and under means. Given the probability for the effect size is either directly given by for or optionally by the odds ratio. An effect size of 0 may not be used in a priori analyses. In our models with more than one covariate, according to [31], the influence of the other covariates on the significance of the test is considered with the help of a correction factor. on the significance of the test is taken into account with the help of a correction factor. This factor depends on the proportion of the variance of explained by the regression relationship, where must lie in the interval [0, 1]. Furthermore, we set up a normal distribution with and Our estimate of the sample size based on the explanations of [30] yields a realistic test power in the result, which is the critical z-size of 1.959 with a minimum sample size of 317, leading to the desired test power of 0.95.

(4) There are no outliers in the observations. Table 3 shows the corresponding properties of the 9 metric-interval scaled variables.

Table 3.

Properties of the 9 metric-interval scaled variables.

No outliers are recognisable based on the values.

(5) In multicollinearity, two or more of the predictors correlate strongly with each other.

In general, whenever one or more exact linear relationships exist between the explanatory variables, the condition of exact collinearity is met. To detect multicollinearity, we use the variance inflation factor (VIF) and the corresponding tolerance to estimate the multicollinearity, whereby a value greater than 10 indicates multicollinearity. The VIF then results from

with as the coefficient of determination of the regression. The models do not show multicollinearity, as can be seen in Table 4. In summary, we conclude that appropriate data are available for our study.

Table 4.

Variance inflation factor (VIF) of the models.

5. Results and Implications

The following shows the results of our models. Logistic regression gives the coefficients as probability estimates of the dependent variable with and its standard error as a measure of the uncertainty of the logistic regression coefficient. The z-value is the regression coefficient divided by the standard error. If the z-value is too large, this indicates that the corresponding true regression coefficient is not 0 and that the corresponding X-variable plays a role. The p-value also gives us the significance value and we define the levels with *** as 1 %, ** as 5 % and * as 10 % significance levels for all models. McFadden R2 or the adjusted R shows us the quality of the models as a coefficient of determination, the AIC the quality comparison and we carry out the likelihood ratio chi-square test to compare the models without independent variables (i.e., only with the constant) with a model with independent variables. With the appropriate degree of freedom k and the information from iteration 0 (the model with only the constant, LLO) and the last iteration (LLM), we calculate:

If the null hypothesis is true, i.e., if all coefficients (outside the constant) are equal to 0, then the model chi-squared statistic has a chi-squared distribution with k degrees of freedom (k = number of estimated coefficients outside the constant). In this case, the model chi-square is highly significant, indicating that at least one variable has an effect that differs from 0.

Furthermore, we interpret the results and point out corresponding implications.

5.1. Demographic Differences

Under the demographic characteristics of the respondents, we define their life situation consisting of personal and family characteristics. Personal characteristics include gender, age, academic background as an educational indicator and general understanding factor for dealing with digital wallets, occupational situation, net income, and family characteristics include relationship status, number of children and the associated decision as to whether the respondent lives as a family member in his or her own residential property (house or condominium). In particular, the level of education as well as the net income should show strong dependencies on the willingness to use digital wallets, since in our view they form the fundamental pillars with regard to the personal attitude towards this topic. The number of children could be a temporal indicator, since the more children the respondents have, the less time they have left to deal with digital topics in general. Living in a relationship and owning their own house or condo represents security for many people, which might encourage them in their mindset more to engage with digital identities beyond that. Table 5 shows the following results from our model:

Table 5.

Results of the demographic differences.

We find that the age, number of children, net income level and academic background of the respondents have a significant influence on the use of digital wallets. Gender, relationship status, employment situation and home ownership have no significant influence. This –that target groups should be classified and addressed according to their age, family situation, income, and academic target groups. As age and income increase, the willingness to use digital identities in wallet apps also decreases. We can attribute this on the one hand to the usability of the wallet apps, and on the other hand to the concern about data loss at an older age, as was also found out by [24]. We interpret the basic understanding of this together with the likelihood of use for people with an academic background. The higher the level of education, the higher the willingness to use. Overall, the model explains almost 54% of the variance, which is a very high and satisfactory value. Consequently, we assume H1.

5.2. Private Individuals’ Experiences with Blockchain Products

In our second model, we test the extent to which respondents who already use blockchain products, i.e., have already heard about them and know how they work, would accept digital identities in digital wallets. If a negative experience is also assumed, the probability decreases, and conversely, if a positive experience is assumed, the respondents tend to use digital wallets more. Table 6 shows the following results from our model:

Table 6.

Results of experiences with blockchain products.

We find that both mere knowledge of the existence of blockchain and more advanced blockchain know-how have a significant impact. Surprisingly, previous use of blockchain products does not exert a significant influence on our model. However, this is consistent with our finding in the first model that people with a high level of education also generally have a higher propensity to use blockchain and that experience with blockchain is therefore not necessarily the decisive factor. For practice, this means that target groups with existing blockchain knowledge should be addressed in particular and that the dissemination of knowledge about blockchain can offer added value in terms of acceptance. Overall, 36% of the variance is explained by the model, which is also a satisfactory value, although the information density as well as the explanatory content of the first model are better.

Furthermore, we would like to find out whether those who have already used digital wallets and have already gained experience with them in terms of convenience, time savings, clarity and self-determination would also adopt digital identities in digital wallets again. To do this, we code the dummy variable with “1” and obtain the following results shown in Table 7:

Table 7.

Results of experiences with blockchain products.

We find that convenience and clarity have a significant influence. Time saving and self-determination, on the other hand, do not exert a significant influence. Convenience and Clarity should also be emphasised in advertising measures. Overall, about 12% of the variance in the observations is explained by the model. However, the results of the first and second model of experience with blockchain products are only partially consistent with H2, as the general use of blockchain products (model 1) has no significant influence and the experience categories (model 2) have only a partially significant influence on the probability of use. The AIC also shows that the previous models are much more informative.

5.3. Affinity of Citizens to (Digital) Financial and ID Products

Similar to the second model, we would like to find out below to what extent respondents who have an affinity with the use of digital financial products are more inclined to adopt digital identities in digital wallets. We base this on the number of bank cards, store cards, online accounts, ID documents, credential documents and certificate proofs used by the respondents. We therefore assume that the more financial products are used, the higher the probability of willingness to use digital identities. We justify this with the time saved, especially when it comes to simplified registration with online shops and corresponding payment methods for the products. It is also easier for users to manage several bank cards if they load them into a digital wallet and use the functions when paying. Table 8 shows the following results from our model:

Table 8.

Results of the affinity of private individuals to (digital) financial products.

We find that experience with loyalty cards, online accounts, credential documents and certification credentials have a significant impact. The experience with ID documents, on the other hand, has no significant influence. For practice, this means that target groups with customer cards, online accounts, testimonial documents, and certification proofs should be addressed in particular. Overall, the model explains about 18% of the variance, although the value is quite low compared to the first model due to the number of underlying explanatory variables here. The results justify the assumption with H3.

5.4. Privacy Concerns

We want to find out to what extent the social acceptance of digital identities in digital wallets depends on data security concerns. For this purpose, the significance of the variable’s importance of data security, trust in government and companies, data security rating and knowledge about data storage will be analysed. Table 9 shows the following results from our model:

Table 9.

Results of the data protection concerns.

We find that the importance of data security, trust in governments and companies and data security assessment have a significant influence. Data storage knowledge, on the other hand, has no significant influence. The values are consistent with the results of [24] regarding citizens’ sense of security. If the importance of data security is personally high and relevant, the willingness to use it is quite low. Citizens’ personal trust in the government and in providers/companies also plays an important role. Accordingly, citizens tend to disclose their data more in “secure and structurally strong” countries, which also increases the willingness to use wallet apps to manage their data. For providers of digital identity products, this means that data security should be well explained and emphasised.

According to the likelihood ration test, the model is significant. Furthermore, 84% of the data points could be predicted correctly. However, the value of the coefficient of determination shows that further variables should be investigated that also contribute to a higher information content (low AIC). However, the results are consistent with H4.

6. Conclusions

This paper provides a quantitative study on the adoption of digital identities. There is little research on blockchain technology, but almost no academic research on the use of digital identities based on blockchain technology. To fill this research gap, we conducted a questionnaire-based survey with 324 participants on the social acceptance of the use of digital identities.

The research results are almost in line with our hypotheses. Social acceptance of the use of digital identities is significantly influenced by demographics, citizens’ (limited) experience with blockchain products, affinity with financial products and privacy concerns.

Providers of digital identity products based on the blockchain should classify and address target groups according to their age, family situation, income and academic target groups. A corresponding user-friendliness of wallet apps is essential for older citizens. The added value lies in particular in convenience and clarity, which should be taken into account in advertising measures and product development. Data protection and security are also more relevant for older citizens than for the younger generation, as also found by [24]. If the importance of data security is personally high and relevant, the willingness to use it is quite low. Citizens’ personal trust in the government and in providers/companies also plays an important role. According to this, citizens tend to disclose their data more in “secure and structurally strong” countries, which also increases the willingness to use wallet apps to manage their data.

Furthermore, sufficient blockchain knowledge should be disseminated and, in particular, target groups with prior blockchain knowledge should be addressed, which goes hand in hand with a basic understanding of how blockchain and wallet apps work. This proves our significant result for people with an academic background and allows us to say that willingness to use increases with a higher level of education. Surprisingly, previous use of blockchain products does not exert a significant influence on our model. However, this is consistent with our finding in the first model that people with a high level of education also generally have a higher willingness to use and thus the experience gained with Blockchain in terms of time savings and self-determination is not necessarily decisive, but advertising measures should particularly emphasise convenience and clarity. In addition, target groups with loyalty cards, online accounts, credentials, and certifications in particular should be addressed. Data security should be well explained and emphasised.

The models do not yet fully explain the dependencies. Future research should therefore look further into the social acceptance of digital identity in order to find further dependencies. In this context, it would be interesting to conduct country-specific and comparative studies that depict the behaviour of different nationalities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.-D.A. and T.F.; methodology, T.F.; software, T.F.; validation, C.-D.A., N.L., D.S., A.Z. and T.F.; formal analysis, N.L. and C.-D.A.; investigation, T.F.; resources, D.S. and A.Z.; data curation, T.F.; writing—original draft preparation, T.F., C.-D.A. and N.L.; writing—review and editing, D.S. and A.Z.; visualisation, C.-D.A. and N.L.; supervision, T.F. and C.-D.A.; project administration, C.-D.A., N.L. and T.F.; and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to single answer retrieval from each of 324 respondents within a survey and include privacy data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Roussos, G.; Peterson, D.; Patel, U. Mobile identity management: An enacted view. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2013, 8, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesdruckerei. Digitale Identitäten—Schlüsselthema unserer Gesellschaft. Available online: https://www.bundesdruckerei.de/de/innovation-hub/digitale-identitaeten-schluesselthema-unserer-gesellschaft (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action. In Focus—Secure Digital Identities. Available online: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Schlaglichter-der-Wirtschaftspolitik/2021/11/05-im-fokus-digitale-identit%C3%A4ten.html (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalifah, A.; Al Amro, S. Understanding the Effect of Privacy Concerns on User Adoption of Identity Management Systems. J. Comput. 2015, 12, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satchell, C.; Shanks, D.; Howard, S.; Murphy, J. Identity crisis: User perspectives on multiplicity and control in federated identity management. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2009, 30, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beduschi, A. Digital identity: Contemporary challenges for data protection, privacy and non-discrimination rights. Big Data Soc. 2019, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatchatourov, A.; Laurent, M.; Levallois-Barth, C. Privacy in Digital Identity Systems: Models, Assessment, and User Adoption. In IFIP International Federation for Information Processing 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugger, J.; Fraefel, M.; Riedl, R. Raising Acceptance of Cross-Border eID Federation by Value Alignment. Electron. J. E-Gov. 2014, 12, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfond, G. A Blockchain Ecosystem for Digital Identity: Improving Service Delivery in Canada’s Public and Private Sectors. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2017, 7, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Hu, W. Determinants of public trust in government: Empirical evidence from urban China. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 83, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemiya, M.; Vanieiev, B. Sora Identity: Secure, Digital Identity on the Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 42nd IEEE International Conference on Computer Software & Applications, Tokyo, Japan, 23–27 July 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bakogiannis, T.; Mytilinis, I.; Doka, K.; Goumas, G. Leveraging Blockchain Technology to Break the Cloud Computing Market Monopoly. Computers 2020, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykidis, I.; Drostos, G.; Rantos, K. The Use of Blockchain Technology in e-Government Services. Computers 2021, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T. Blockchain-Based Internet of Things: Review, Current Trends, Applications, and Future Challenges. Computers 2023, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaiokrassas, G.; Skoufis, P.; Voutyras, O.; Kawasaki, T.; Gallissot, M.; Azzabi, R.; Tsuge, A.; Litke, A.; Okoshi, T.; Nakazawa, J.; et al. Combining Blockchains, Smart Contracts, and Complex Sensors Management Platform for Hyper-Connected SmartCities: An IoT Data Marketplace Use Case. Computers 2021, 10, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckle, S.; Bhattacharya, R.; White, M.; Beloff, N. Internet of Things, Blockchain and Shared Economy Applications. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 98, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Caramés, T.M.; Fraga-Lamas, P. A Review on the Use of Blockchain for the Internet of Things. IEEE 2018, 6, 32979–33001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, P.; Chen, T.; Luo, X.; Wen, Q. A Survey on the Security of Blockchain Systems. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 107, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, H.; Mohamed, A.; Guizani, M. A Survey of Blockchain Enabled Cyber-Physical Systems. Sensors 2020, 20, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. A Critical Review of Blockchain Acceptance Models—Blockchain Technology Adoption Frameworks and Applications. Computers 2022, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, U.; Kar, A.K.; Gupta, M. Digital Identity Evaluation Framework for Social Welfare. In Re-Imagining Diffusion and Adoption of Information Technology and Systems: A Continuing Conversation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalvet, T.; Tiits, M.; Laas-Mikko, K. Public Acceptance of Advanced Identity Documents. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Galway, Ireland, 4–6 April 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, M.; Isabelle, D.A.; Leminen, S. The Acceptance of Digital Surveillance in an Age of Big Data. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2021, 11, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiits, M.; Kalvet, T.; Laas-Mikko, K. Social Acceptance of ePassports. Lect. Notes Inform. 2014, 230, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tiits, M.; Ubakivi-Hadachi, P. Common Patterns on Identity Document Usage in EU. EKSISTENZ Working Paper, 2015, 9.1. Available online: https://www.ibs.ee/en/publications/tackling-identity-theft-with-a-harmonized-framework-allowing-a-sustainable-and-robust-identity-for-european-citizens/ (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Tiits, M.; Ubakivi-Hadachi, P. Societal Risks Deriving from Identity Theft; EKSISTENZ Working Paper 9.2; Institute of Baltic Studies: Tartu, Estonia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Peterson, H.M., Jr.; Sun, W. Perception of Digital Surveillance: A Comparative Study of High School Students in the U.S. and China. Issues Inf. Syst. 2017, 18, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R. Risks inherent in the digital surveillance economy: A research agenda. J. Inf. Technol. 2019, 34, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, F.Y.; Bloch, D.A.; Larsen, M.D. A simple method of sample size calculation for linear and logistic regression. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).