Phase II Study of Pegvorhyaluronidase Alfa (PEGPH20) and Pembrolizumab for Patients with Hyaluronan-High, Pretreated Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: PCRT16-001

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Eligibility

2.2. Study Design and Treatments

2.3. Biomarker Analyses

2.3.1. Plasma HA

2.3.2. TCR Sequencing

2.3.3. Immune Phenotyping by Flow Cytometry

2.3.4. PD-L1

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patients

3.2. Safety and Toxicity

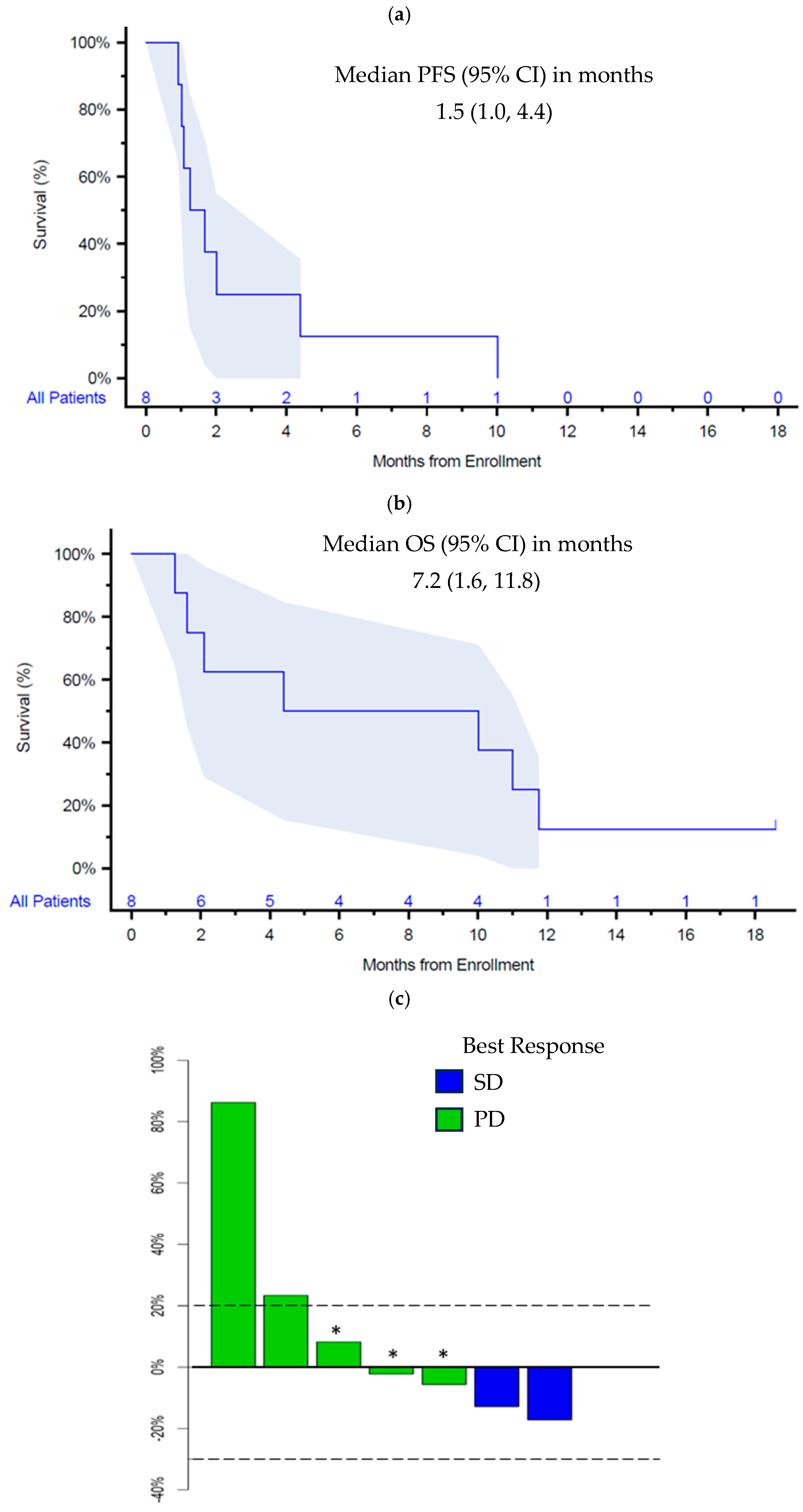

3.3. Efficacy

3.4. Molecular Biomarkers and Correlations with Efficacy

3.5. Genomics

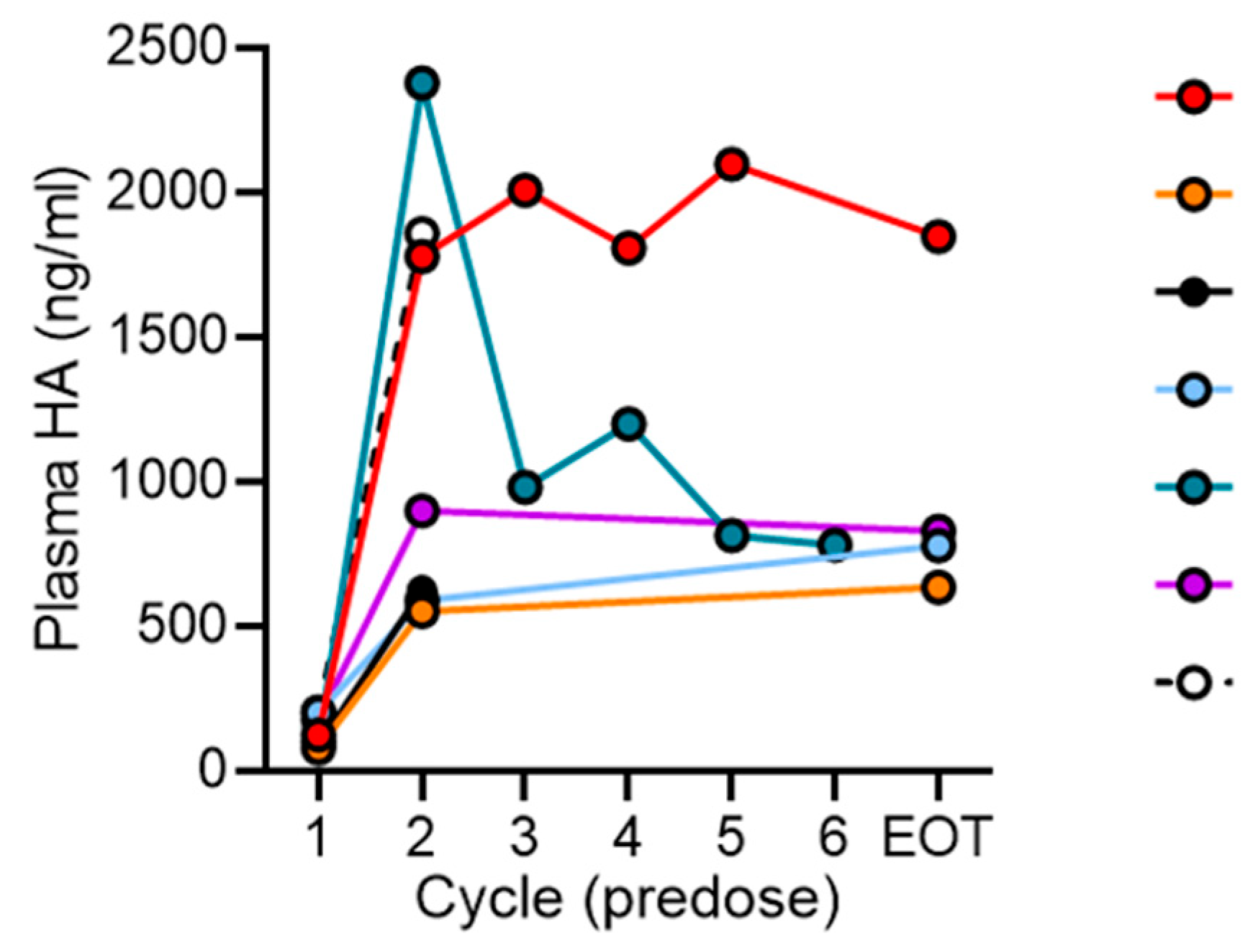

3.6. Plasma HA

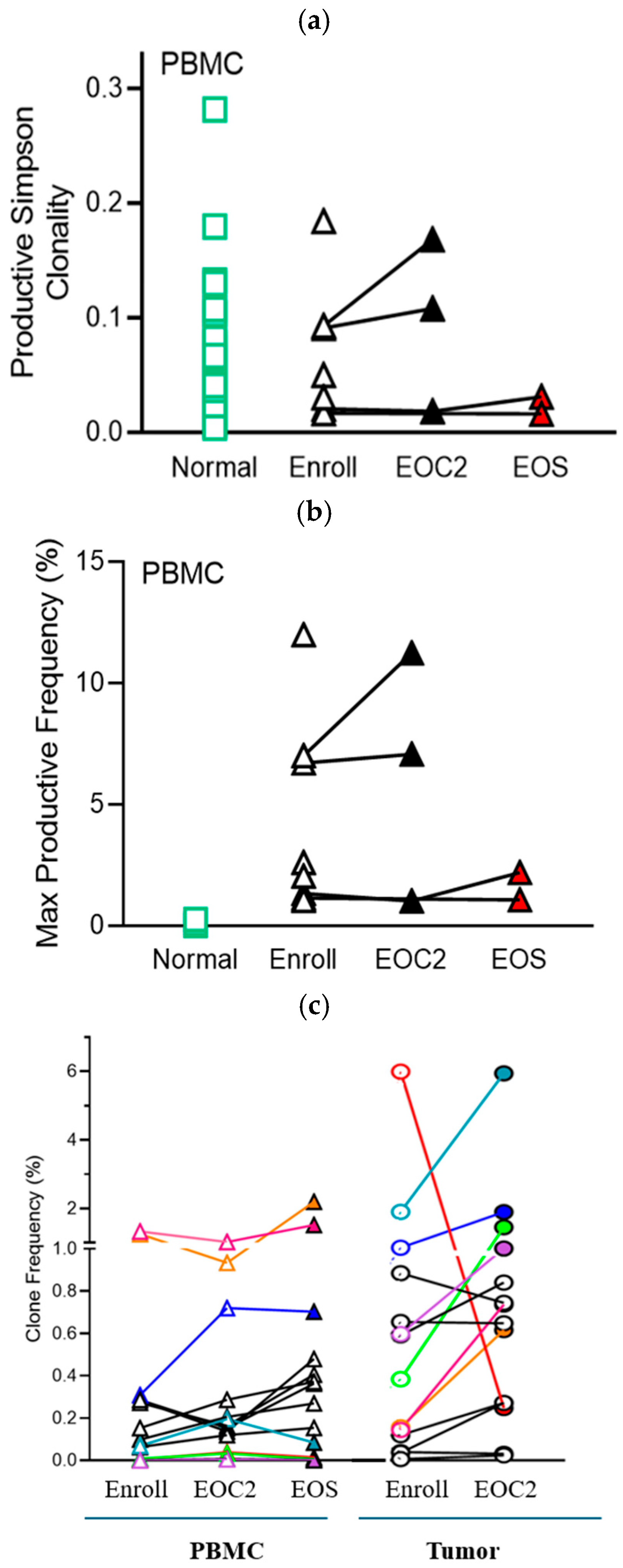

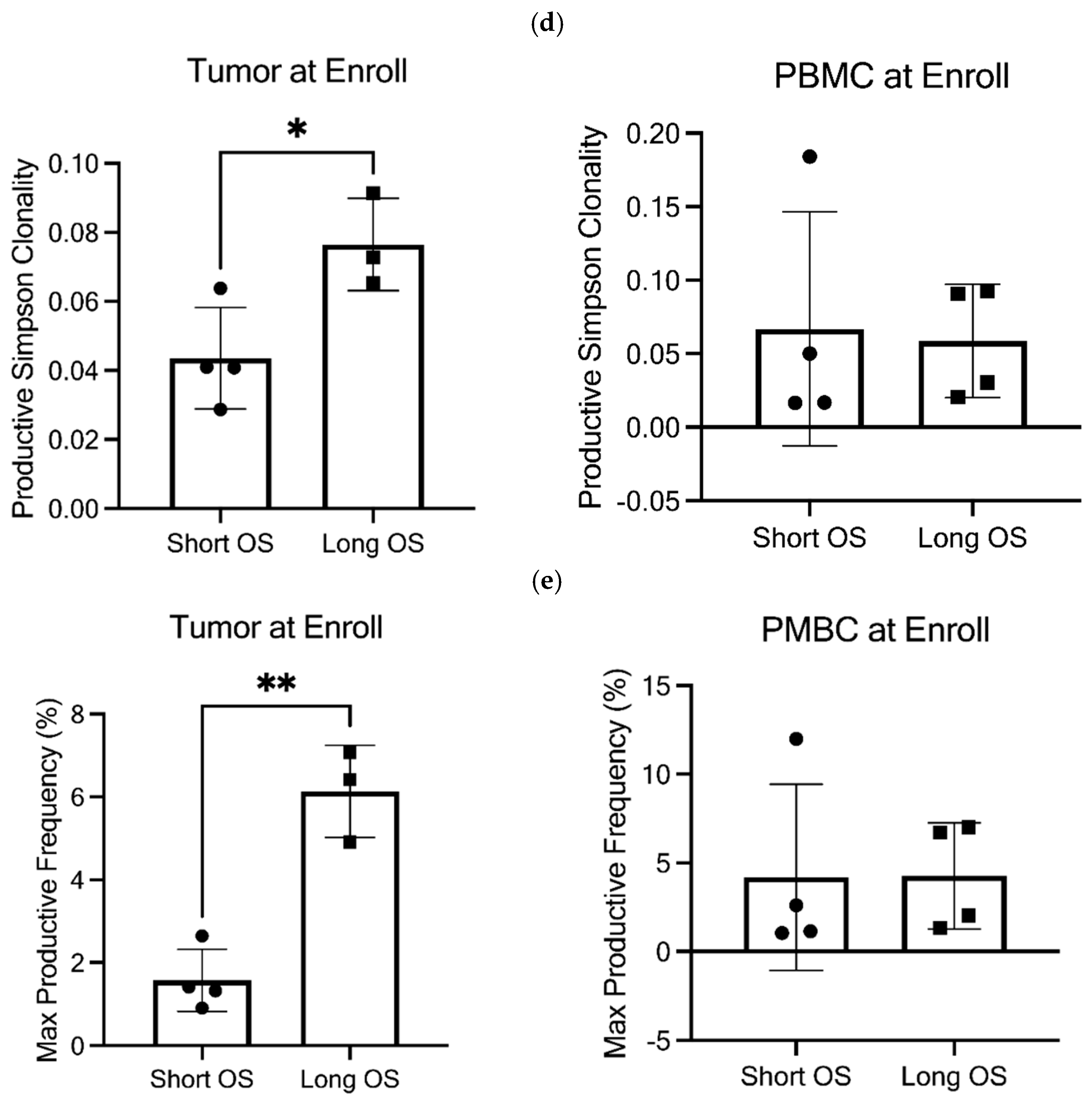

3.7. TCR Clonality

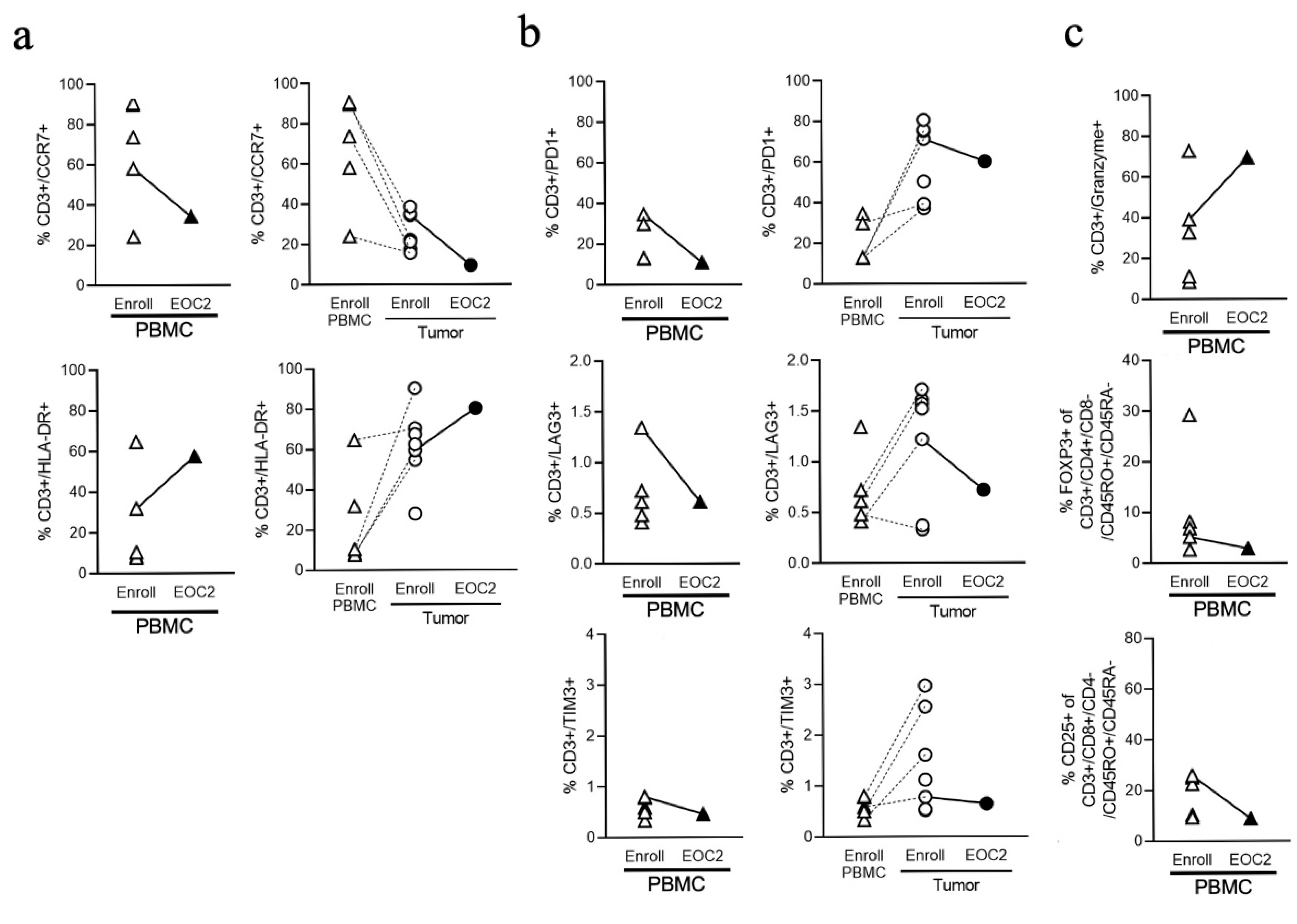

3.8. Immune Phenotyping

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang-Gillam, A.; Hubner, R.A.; Siveke, J.T.; Von Hoff, D.D.; Belanger, B.; de Jong, F.A.; Mirakhur, B.; Chen, L.T. NAPOLI-1 phase 3 study of liposomal irinotecan in metastatic pancreatic cancer: Final overall survival analysis and characteristics of long-term survivors. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 108, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiorean, E.G.; Guthrie, K.A.; Philip, P.A.; Swisher, E.M.; Jalikis, F.; Pishvaian, M.J.; Berlin, J.; Noel, M.S.; Suga, J.M.; Garrido-Laguna, I.; et al. Randomized phase II study of PARP inhibitor ABT-888 (veliparib) with modified FOLFIRI versus FOLFIRI as second-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer: SWOG S1513. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 6314–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, B.M.; Basu Mallick, A.; Horick, N.K.; Wang-Gillam, A.; Hosein, P.J.; Morse, M.A.; Beg, M.S.; Murphy, J.E.; Mavroukakis, S.; Zaki, A.; et al. Effect of a MUC5AC antibody (NPC-1C) administered with second-line gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel on the survival of patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2249720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tempero, M.A.; Malafa, M.P.; Basturk, O.; Benson, A.B., III; Cardin, D.B.; Chiorean, E.G.; Christensen, J.A.; Chung, V.; Czito, B.; Del Chiaro, M.; et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma v.2. 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?id=1455 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Nomi, T.; Sho, M.; Akahori, T.; Hamada, K.; Kubo, A.; Kanehiro, H.; Nakamura, S.; Enomoto, K.; Yagita, H.; Azuma, M.; et al. Clinical significance and therapeutic potential of the programmed death-1 ligand/programmed death-1 pathway in human pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 2151–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, M.; Giese, N.A.; Kleeff, J.; Giese, T.; Gaida, M.M.; Bergmann, F.; Laschinger, M.; Büchler, M.W.; Friess, H. Clinical significance and regulation of the costimulatory molecule B7-H1 in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008, 268, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, G.C.L.; Zhen, D.B.; Pillarisetty, V.G.; Chiorean, E.G. Combination immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer: Challenges and future considerations. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 18, 1173–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, M.H.; O’Reilly, E.M.; Varadhachary, G.; Wolff, R.A.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Ko, A.H.; Fisher, G.; Rahma, O.; Lyman, J.P.; Cabanski, C.R.; et al. CD40 agonistic monoclonal antibody APX005M (sotigalimab) and chemotherapy, with or without nivolumab, for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: An open-label, multicentre, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, A.R.; Szabolcs, A.; Allen, J.N.; Clark, J.W.; Wo, J.Y.; Raabe, M.; Thel, H.; Hoyos, D.; Mehta, A.; Arshad, S.; et al. Radiation therapy enhances immunotherapy response in microsatellite stable colorectal and pancreatic adenocarcinoma in a phase II trial. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.D.; Jiang, X.; Sullivan, K.M.; Jalikis, F.G.; Smythe, K.S.; Abbasi, A.; Vignali, M.; Park, J.O.; Daniel, S.K.; Pollack, S.M.; et al. Mobilization of CD8+ T cells via CXCR4 blockade facilitates PD-1 checkpoint therapy in human pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3934–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockorny, B.; Macarulla, T.; Semenisty, V.; Borazanci, E.; Wolpin, B.M.; Stemmer, S.M.; Golan, T.; Geva, R.; Borad, M.J.; Pedersen, K.S.; et al. Motixafortide and pembrolizumab combined to nanoliposomal irinotecan, fluorouracil, and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer: The COMBAT/KEYNOTE-202 trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 5020–5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marabelle, A.; Le, D.T.; Ascierto, P.A.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; De Jesus-Acosta, A.; Delord, J.P.; Geva, R.; Gottfried, M.; Penel, N.; Hansen, A.R.; et al. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair-deficient cancer: Results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarchoan, M.; Albacker, L.A.; Hopkins, A.C.; Montesion, M.; Murugesan, K.; Vithayathil, T.T.; Zaidi, N.; Azad, N.S.; Laheru, D.A.; Frampton, G.M.; et al. PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden are independent biomarkers in most cancers. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e126908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawlor, R.T.; Mattiolo, P.; Mafficini, A.; Hong, S.M.; Piredda, M.L.; Taormina, S.V.; Malleo, G.; Marchegiani, G.; Pea, A.; Salvia, R.; et al. Tumor mutational burden as a potential biomarker for immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer: Systematic review and still-open questions. Cancers 2021, 13, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provenzano, P.P.; Cuevas, C.; Chang, A.E.; Goel, V.K.; Von Hoff, D.D.; Hingorani, S.R. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provenzano, P.P.; Hingorani, S.R. Hyaluronan, fluid pressure, and stromal resistance in pancreas cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobetz, M.A.; Chan, D.S.; Neesse, A.; Bapiro, T.E.; Cook, N.; Frese, K.K.; Feig, C.; Nakagawa, T.; Caldwell, M.E.; Zecchini, H.I.; et al. Hyaluronan impairs vascular function and drug delivery in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gut 2013, 62, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, N.C.; Nekoroski, T.; Zhao, C.; Symons, R.; Jiang, P.; Frost, G.I.; Huang, Z.; Shepard, H.M. Tumor-associated hyaluronan limits efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollyky, P.L.; Lord, J.D.; Masewicz, S.A.; Evanko, S.P.; Buckner, J.H.; Wight, T.N.; Nepom, G.T. Cutting edge: High molecular weight hyaluronan promotes the suppressive effects of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollyky, P.L.; Falk, B.A.; Long, S.A.; Preisinger, A.; Braun, K.R.; Wu, R.P.; Evanko, S.P.; Buckner, J.H.; Wight, T.N.; Nepom, G.T. CD44 costimulation promotes FoxP3+ regulatory T cell persistence and function via production of IL-2, IL-10, and TGF-beta. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 2232–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, E.R.; Chen, J.; D’Apuzzo, M.; Lampa, M.G.; Kaltcheva, T.I.; Thompson, C.B.; Ludwig, T.; Chung, V.; Diamond, D.J. Salmonella-based therapy targeting indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase coupled with enzymatic depletion of tumor hyaluronan induces complete regressions of aggressive pancreatic tumors. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clift, R.; Souratha, J.; Garrovillo, S.A.; Zimmerman, S.; Blouw, B. Remodeling the tumor microenvironment sensitizes breast tumors to anti-programmed death-ligand 1 immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 4149–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, S.R.; Harris, W.P.; Beck, J.T.; Berdov, B.A.; Wagner, S.A.; Pshevlotsky, E.M.; Tjulandin, S.A.; Gladkov, O.A.; Holcombe, R.F.; Korn, R.; et al. Phase Ib study of PEGylated recombinant human hyaluronidase and gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 2848–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, S.R.; Zheng, L.; Bullock, A.J.; Seery, T.E.; Harris, W.P.; Sigal, D.S.; Braiteh, F.; Ritch, P.S.; Zalupski, M.M.; Bahary, N.; et al. HALO 202: Randomized phase II study of PEGPH20 plus nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine versus nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine in patients with untreated, metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Tempero, M.A.; Sigal, D.; Oh, D.Y.; Fazio, N.; Macarulla, T.; Hitre, E.; Hammel, P.; Hendifar, A.E.; Bates, S.E.; et al. Randomized phase III trial of pegvorhyaluronidase alfa with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for patients with hyaluronan-high metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3185–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, G.I.; Stern, R. A microtiter-based assay for hyaluronidase activity not requiring specialized reagents. Anal. Biochem. 1997, 251, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robins, H.S.; Srivastava, S.K.; Campregher, P.V.; Wacher, A.; Turtle, C.J.; Kahsai, O.; Riddell, S.R.; Warren, E.H.; Carlson, C.S. Overlap and effective size of the human CD8+ T cell receptor repertoire. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010, 2, 47ra64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, A.C.; Yarchoan, M.; Durham, J.N.; Yusko, E.C.; Rytlewski, J.A.; Robins, H.S.; Laheru, D.A.; Le, D.T.; Lutz, E.R.; Jaffee, E.M. T cell receptor repertoire features associated with survival in immunotherapy-treated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e122092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Jia, R.; Lv, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Han, G. TCR β chain repertoire characteristic between healthy human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Biosci. Rep. 2024, 44, BSR20231653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, J.M.; Pagliano, O.; Fourcade, J.; Sun, Z.; Wang, H.; Sander, C.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Chen, T.H.; Maurer, M.; Korman, A.J.; et al. TIGIT and PD-1 impair tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in melanoma patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 2046–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Telang, G.; Bennur, D.; Chougule, S.; Dandge, P.B.; Joshi, S.; Vyas, N. T Cell exhaustion and activation markers in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2024, 55, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahkola, K.; Ahtiainen, M.; Mecklin, J.P.; Kellokumpu, I.; Laukkarinen, J.; Tammi, M.; Tammi, R.; Väyrynen, J.P.; Böhm, J. Stromal hyaluronan accumulation is associated with low immune response and poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wu, J.; Cao, W.; Chen, Q.; Shao, Z.; Hu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Weng, W.; Meng, T.; Meng, X.; et al. A novel FAP-targeting antibody-exatecan conjugate improves immune checkpoint blockade by reversing immunosuppressive microenvironment in pancreatic cancer. Oncogene 2025, 44, 4114–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, A.B.; Wang, J.; Davelaar, J.; Baker, A.; Li, K.; Niu, N.; Wang, J.; Shao, Y.; Funes, V.; Li, P.; et al. Dual stromal targeting sensitizes pancreatic adenocarcinoma for anti-programmed cell death protein 1 therapy. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 1267–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang-Gillam, A.; Lim, K.H.; McWilliams, R.; Suresh, R.; Lockhart, A.C.; Brown, A.; Breden, M.; Belle, J.I.; Herndon, J.; Bogner, S.J.; et al. Defactinib, pembrolizumab, and gemcitabine in patients with advanced treatment refractory pancreatic cancer: A phase I dose escalation and expansion study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 5254–5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiorean, E.G.; Picozzi, V.; Li, C.P.; Peeters, M.; Maurel, J.; Singh, J.; Golan, T.; Blanc, J.F.; Chapman, S.C.; Hussain, A.M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of abemaciclib alone and with PI3K/mTOR inhibitor LY3023414 or galunisertib versus chemotherapy in previously treated metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 20353–20364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, D.T.; Picozzi, V.J.; Ko, A.H.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Kindler, H.; Wang-Gillam, A.; Oberstein, P.; Morse, M.A.; Zeh, H.J., 3rd; Weekes, C.; et al. Results from a phase IIb, randomized, multicenter study of GVAX pancreas and CRS-207 compared with chemotherapy in adults with previously treated metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (ECLIPSE study). Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5493–5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrero, G.; Datta, J.; Dennison, J.; Sussman, D.A.; Lohse, I.; Merchant, N.B.; Hosein, P.J. Ipilimumab/nivolumab therapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic or biliary cancer with homologous recombination deficiency pathogenic germline variants. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothuri, V.S.; Hogg, G.D.; Conant, L.; Borcherding, N.; James, C.A.; Mudd, J.; Williams, G.; Seo, Y.D.; Hawkins, W.G.; Pillarisetty, V.G.; et al. Intratumoral T-cell receptor repertoire composition predicts overall survival in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncoimmunology 2024, 13, 2320411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, J.M.; Eng, J.R.; Pelz, C.; MacPherson-Hawthorne, K.; Worth, P.J.; Sivagnanam, S.; Keith, D.J.; Owen, S.; Langer, E.M.; Grossblatt-Wait, A.; et al. Ongoing replication stress tolerance and clonal T cell responses distinguish liver and lung recurrence and outcomes in pancreatic cancer. Nat. Cancer 2025, 6, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretto, R.; Rossini, D.; Catteau, A.; Antoniotti, C.; Giordano, M.; Boccaccino, A.; Ugolini, C.; Proietti, A.; Conca, V.; Kassambara, A.; et al. Dissecting tumor lymphocyte infiltration to predict benefit from immune-checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic colorectal cancer: Lessons from the AtezoT RIBE study. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiringhelli, F.; Bibeau, F.; Greillier, L.; Fumet, J.D.; Ilie, A.; Monville, F.; Laugé, C.; Catteau, A.; Boquet, I.; Majdi, A.; et al. Immunoscore immune checkpoint using spatial quantitative analysis of CD8 and PD-L1 markers is predictive of the efficacy of anti- PD1/PD-L1 immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. EBioMedicine 2023, 92, 104633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, A.; Antoniotti, C.; Cremolini, C.; Galon, J. Light on life: Immunoscore immune-checkpoint, a predictor of immunotherapy response. Oncoimmunology 2023, 12, 2243169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, A.H.; Kim, K.P.; Siveke, J.T.; Lopez, C.D.; Lacy, J.; O’Reilly, E.M.; Macarulla, T.; Manji, G.A.; Lee, J.; Ajani, J.; et al. Atezolizumab Plus PEGPH20 versus chemotherapy in advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and gastric cancer: MORPHEUS phase Ib/II umbrella randomized study platform. Oncologist 2023, 28, 553-e472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (median, years) | 68 | |

| Range | (60–73) | |

| <65 | 1 | 12.5 |

| ≥65 | 7 | 87.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1 | 12.5 |

| Male | 7 | 87.5 |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 1 | 12.5 |

| Black African American | 0 | 0 |

| White | 7 | 87.5 |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0–1 | 8 | 100 |

| Sites of metastatic disease | ||

| Liver | 5 | 62.5 |

| Lung | 1 | 12.5 |

| Lymph nodes | 3 | 37.5 |

| Peritoneum | 5 | 62.5 |

| Number of prior therapies | ||

| Median (range) | 2 (1–4) | |

| Prior therapies | ||

| Gemcitabine/nab-Paclitaxel | 6 | 75 |

| FOLFIRINOX | 4 | 50 |

| FOLFOX | 2 | 25 |

| 5-FU/leucovorin | 1 | 12.5 |

| Gemcitabine | 1 | 12.5 |

| RX-3117/nab-Paclitaxel | 1 | 12.5 |

| Adverse Event | Grade 1 n (%) | Grade 2 n (%) | Grade 3 n (%) | Grade 4 n (%) | All Grades n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRAE | |||||

| dyspnea | 0 | 1 (13) | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) |

| edema limbs | 2 (25) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) |

| fatigue | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) | 0 | 1 (13) |

| hypothyroidism | 0 | 1 (13) | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) |

| muscle cramps | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) |

| myalgia | 1 (13) | 3 (38) | 0 | 0 | 4 (50) |

| TEAE | |||||

| abdominal pain | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) | 0 | 2 (25) |

| diarrhea | 2 (25) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) |

| edema limbs | 2 (25) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) |

| muscle cramps | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) |

| myalgia | 1 (12.5) | 3 (37.5) | 0 | 0 | 4 (50) |

| vomiting | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) |

| Pt | Molecular Profile | PD-L1 MPS | TMB (m/Mb) | Prior Therapies | Best Response | PFS (mo) | Subsequent Therapies | OS (mo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Not done | 3 | FFOX Gem/nabP Gem FFOX | NE | 1.3 | none | 1.3 | |

| 2 | MSS, KRAS WT, ATM L1238fs*6, RET-PCM1 fusion, RNF43 R132 * | 1 | 6 | RX3117/nabP FOLFOX | PD | 2.0 | nal-iri/5FU | 27.6+ |

| 3 | Not done | 1 | Gem/nabP 5FU/LV | PD | 1.0 | none | 2.1 | |

| 4 | MSS, KRAS G12R, FGFR1 amp, ZNF703 amp, NSD3 amp, SMAD4 1309-1_1309GG > TTT, TP53 V157D, RB1 1369fs*8, PRKAR1A R96 * | 1 | 1 | FFOX Gem/nabP | PD | 1.2 | nal-iri/5FU | 11.9 |

| 5 | Not done | 1 | FOLFOX FFOX | SD | 10.2 | Gem | 10.2 | |

| 6 | Not done | 0 | Gem/nabP | SD | 4.5 | FOLFOX | 11.2 | |

| 7 | MSS, KRAS G12D, BRCA2 T207A, TP53 R273L | NE | <10 * | Gem/nabP | PD | 1.1 | none | 1.6 |

| 8 | MSS, KRAS mut, TP53 mut, CDKN2A mut, CDH1 mut & | 2 | <10 * | FFOX Gem/nabP | PD | 1.7 | none | 4.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chiorean, E.G.; Damle, S.R.; Zhen, D.B.; Whittle, M.; George, B.; Hochster, H.; Coveler, A.L.; Hendifar, A.; Dragovich, T.; Safyan, R.A.; et al. Phase II Study of Pegvorhyaluronidase Alfa (PEGPH20) and Pembrolizumab for Patients with Hyaluronan-High, Pretreated Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: PCRT16-001. Cancers 2026, 18, 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030507

Chiorean EG, Damle SR, Zhen DB, Whittle M, George B, Hochster H, Coveler AL, Hendifar A, Dragovich T, Safyan RA, et al. Phase II Study of Pegvorhyaluronidase Alfa (PEGPH20) and Pembrolizumab for Patients with Hyaluronan-High, Pretreated Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: PCRT16-001. Cancers. 2026; 18(3):507. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030507

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiorean, Elena Gabriela, Sheela R. Damle, David B. Zhen, Martin Whittle, Ben George, Howard Hochster, Andrew L. Coveler, Andrew Hendifar, Tomislav Dragovich, Rachael A. Safyan, and et al. 2026. "Phase II Study of Pegvorhyaluronidase Alfa (PEGPH20) and Pembrolizumab for Patients with Hyaluronan-High, Pretreated Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: PCRT16-001" Cancers 18, no. 3: 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030507

APA StyleChiorean, E. G., Damle, S. R., Zhen, D. B., Whittle, M., George, B., Hochster, H., Coveler, A. L., Hendifar, A., Dragovich, T., Safyan, R. A., King, G. T., Harris, W. P., Dion, B., Stoll D’Astice, A., Lee, A., Thorsen, S., Kugel, S., Rosenthal, A., & Hingorani, S. (2026). Phase II Study of Pegvorhyaluronidase Alfa (PEGPH20) and Pembrolizumab for Patients with Hyaluronan-High, Pretreated Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: PCRT16-001. Cancers, 18(3), 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030507