MRI-Based Radiomics for Non-Invasive Prediction of Molecular Biomarkers in Gliomas

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

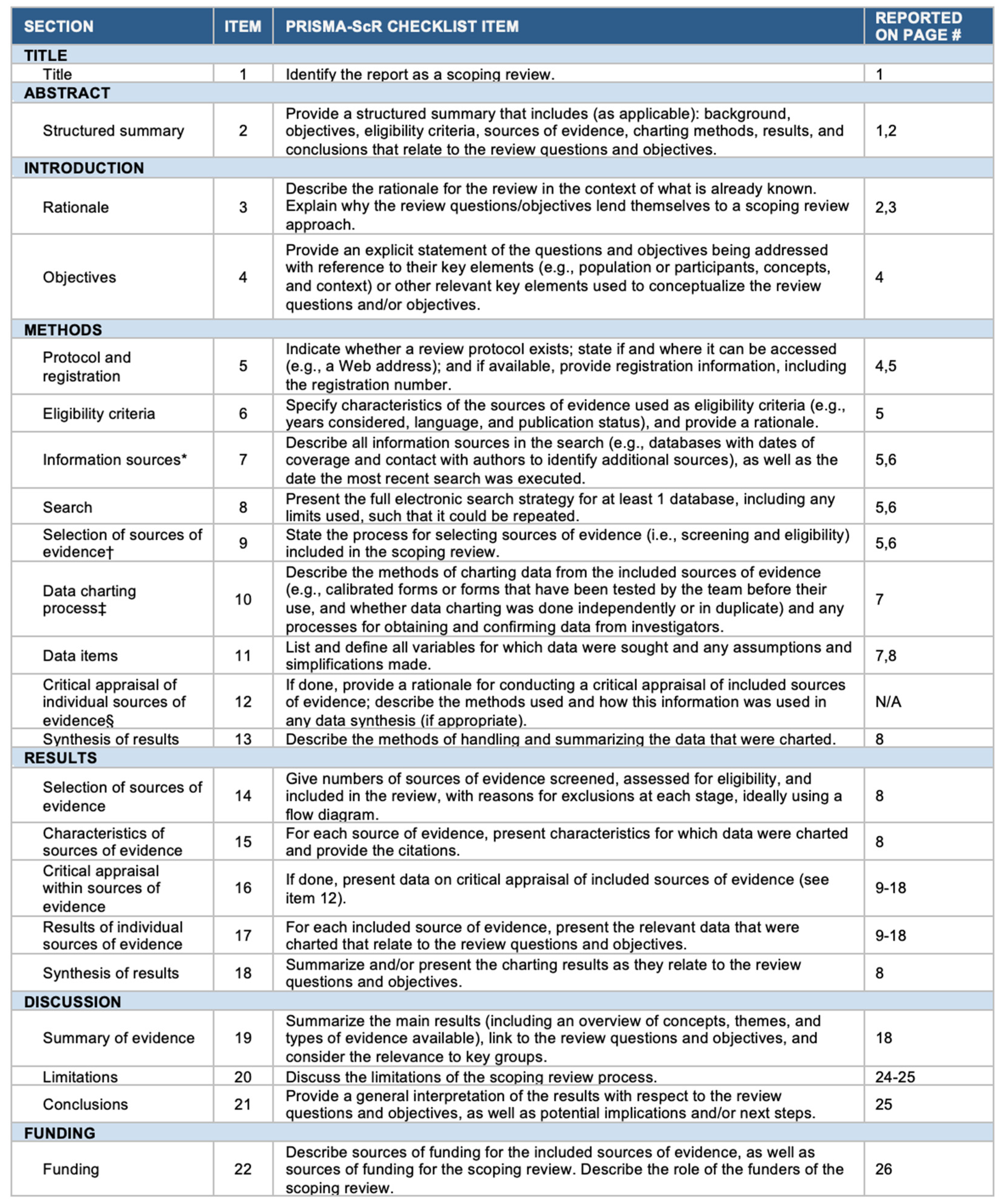

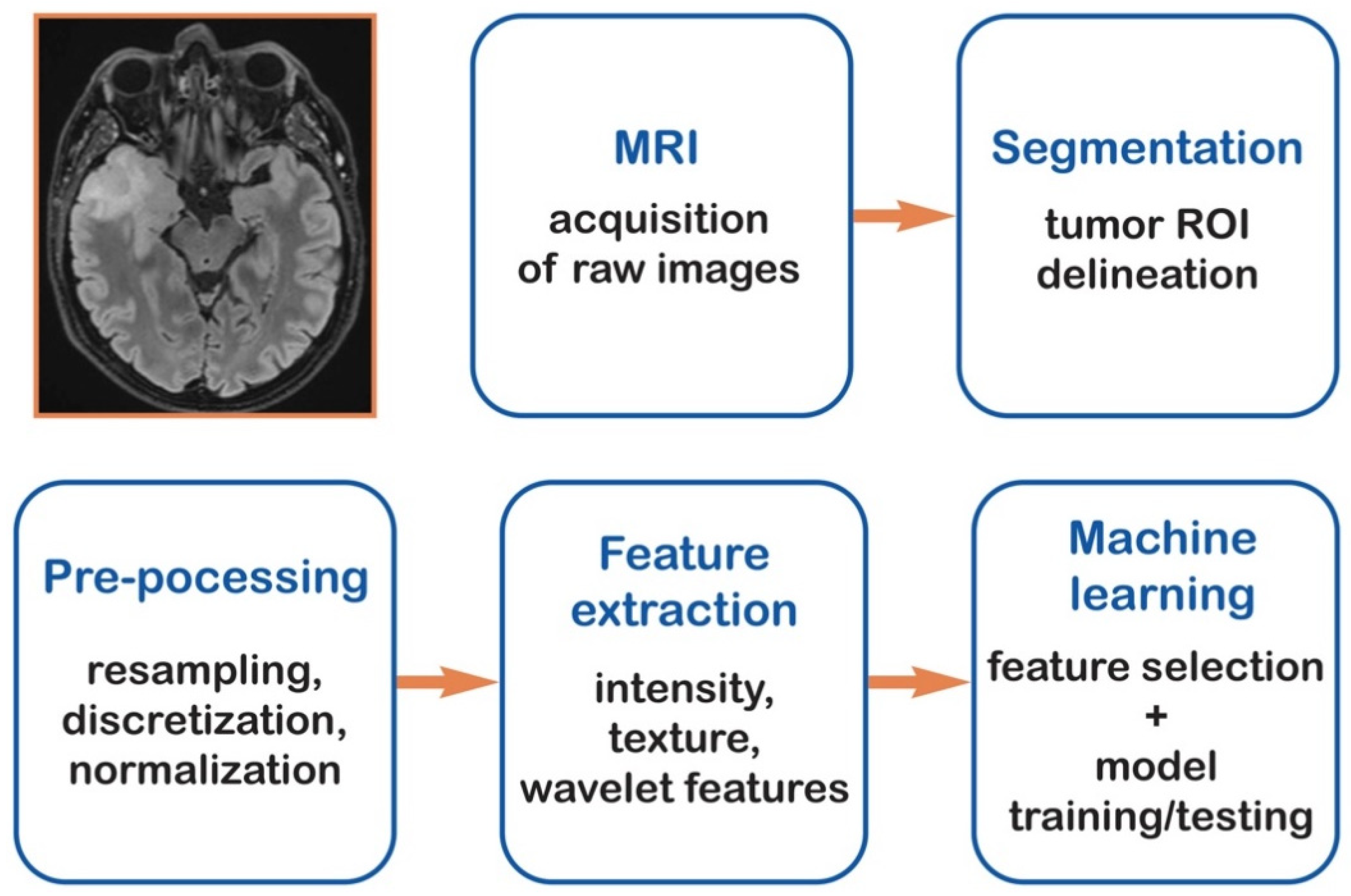

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Outcomes

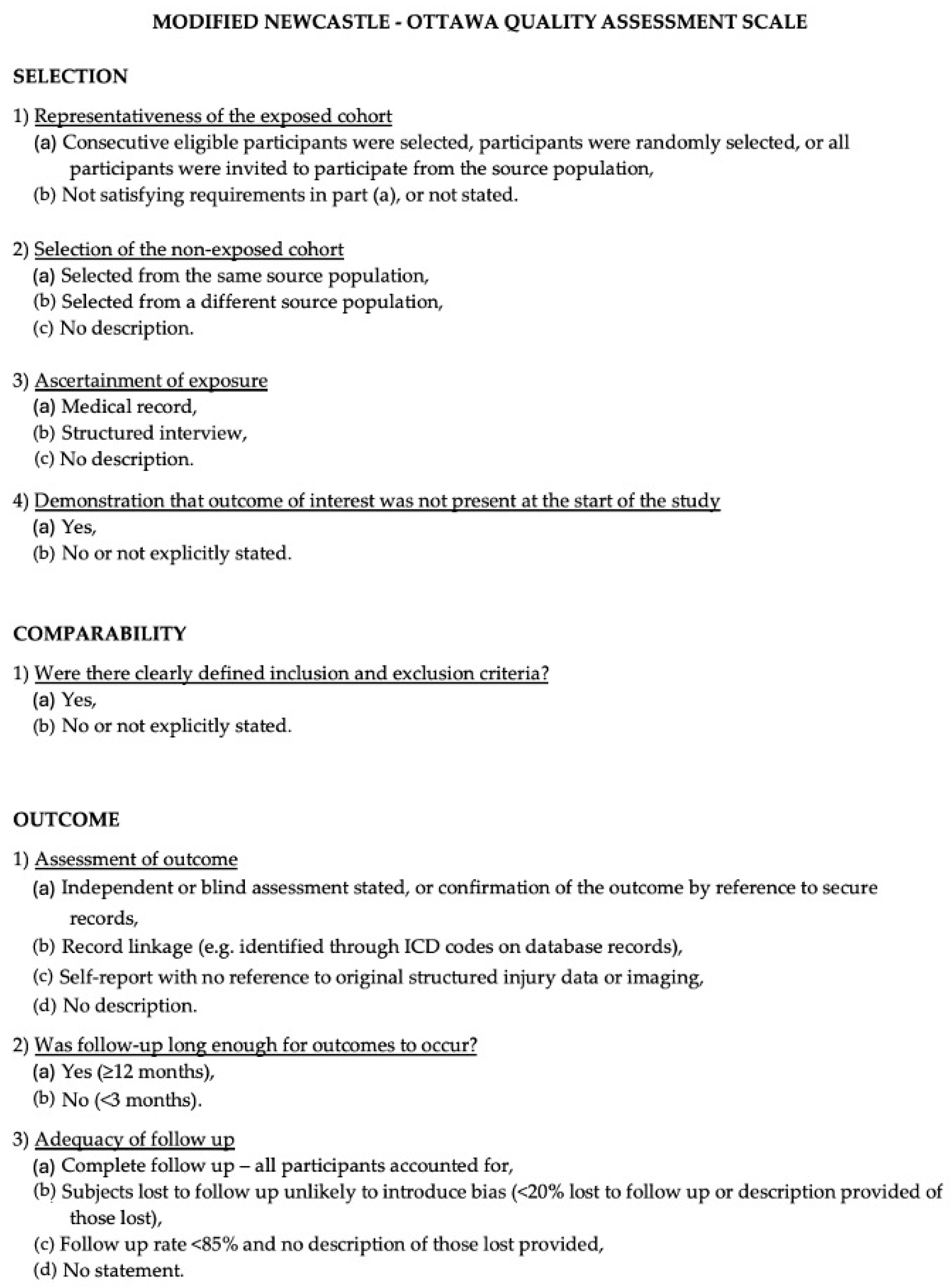

2.4. Radiomics Quality Assessment

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

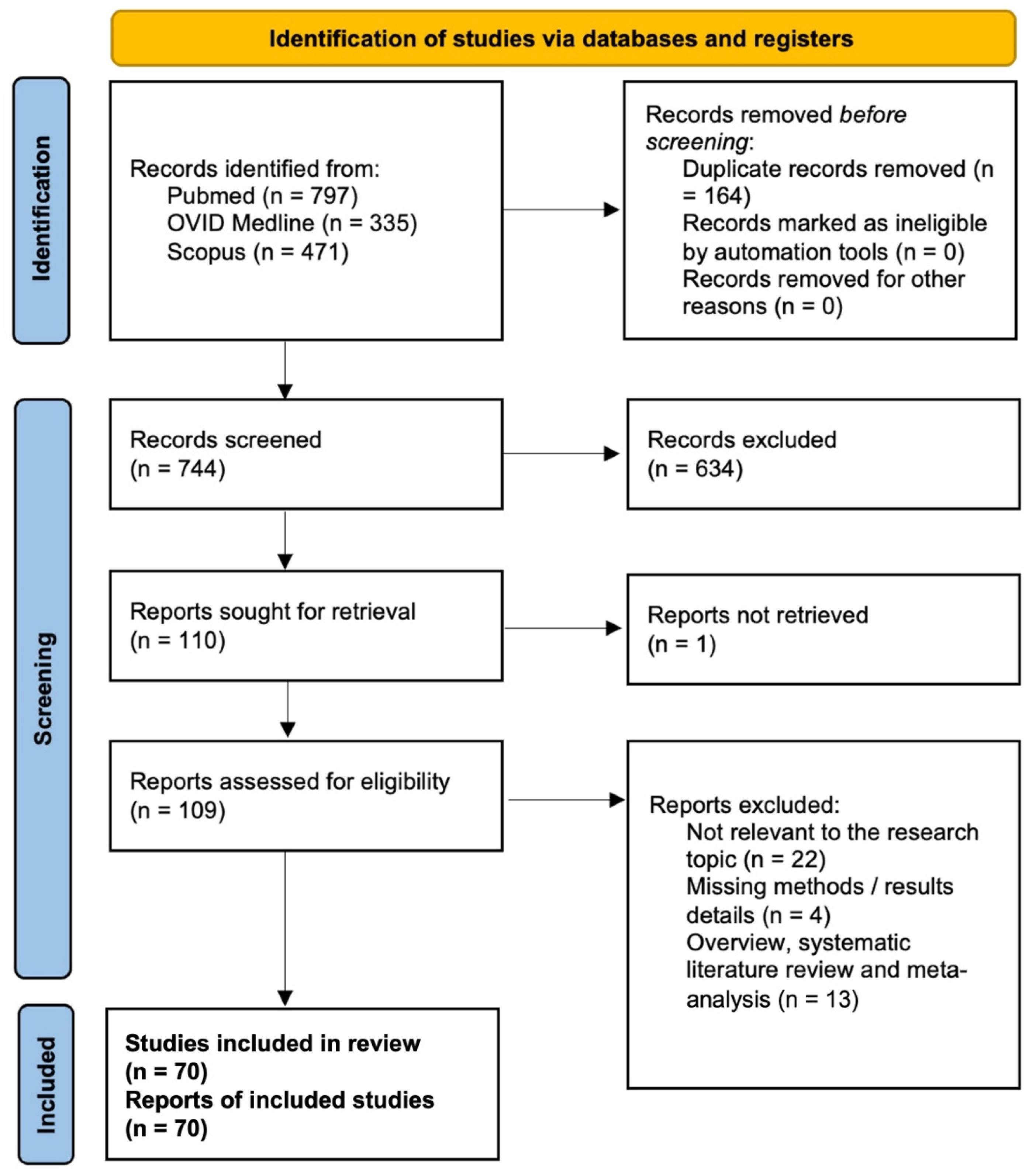

3. Results

3.1. PRISMA

3.2. Data Analysis

3.3. Handcrafted Radiomics and Deep Learning

3.4. RQS and IBSI Assessment

3.5. NOS Assessment

3.6. Descriptive Summary of Methodological and Performance Metrics

4. Discussion

4.1. Radiomics Application for Non-Invasive Molecular Profiling

4.1.1. IDH Mutation

4.1.2. 1p/19q Codeletion

4.1.3. p53

4.1.4. PTEN

4.1.5. TERT Promoter Mutation

4.1.6. ATRX

4.1.7. VEGF

4.1.8. EGFR

4.1.9. Ki-67

4.1.10. MGMT Methylation

4.2. Integration of Deep Learning Algorithms in Radiomics

4.3. Radiomics Applications to Characterize the Tumor Microenvironment

4.4. Radiomics Integration with Multi-Omics

4.5. Discrepancy Between Clinical and Technical Quality

4.6. Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

4.7. Future Integration of Radiomics and Biopsy

4.8. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Agosti, E.; Antonietti, S.; Ius, T.; Fontanella, M.M.; Zeppieri, M.; Panciani, P.P. Glioma Stem Cells as Promoter of Glioma Progression: A Systematic Review of Molecular Pathways and Targeted Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosti, E.; Zeppieri, M.; Ghidoni, M.; Ius, T.; Tel, A.; Fontanella, M.M.; Panciani, P.P. Role of Glioma Stem Cells in Promoting Tumor Chemo- and Radioresistance: A Systematic Review of Potential Targeted Treatments. World J. Stem Cells 2024, 16, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agosti, E.; Garaba, A.; Antonietti, S.; Ius, T.; Fontanella, M.M.; Zeppieri, M.; Panciani, P.P. CAR-T Cells Therapy in Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review on Molecular Targets and Treatment Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agosti, E.; Zeppieri, M.; De Maria, L.; Tedeschi, C.; Fontanella, M.M.; Panciani, P.P.; Ius, T. Glioblastoma Immunotherapy: A Systematic Review of the Present Strategies and Prospects for Advancements. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, L.; Panciani, P.P.; Zeppieri, M.; Ius, T.; Serioli, S.; Piazza, A.; Di Giovanni, E.; Fontanella, M.M.; Agosti, E. A Systematic Review of the Metabolism of High-Grade Gliomas: Current Targeted Therapies and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosti, E.; Antonietti, S.; Ius, T.; Fontanella, M.M.; Zeppieri, M.; Panciani, P.P. A Systematic Review of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: A Potential Treatment for Glioblastoma. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstock, J.D.; Gary, S.E.; Klinger, N.; Valdes, P.A.; Ibn Essayed, W.; Olsen, H.E.; Chagoya, G.; Elsayed, G.; Yamashita, D.; Schuss, P.; et al. Standard Clinical Approaches and Emerging Modalities for Glioblastoma Imaging. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2022, 4, vdac080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martucci, M.; Russo, R.; Schimperna, F.; D’Apolito, G.; Panfili, M.; Grimaldi, A.; Perna, A.; Ferranti, A.M.; Varcasia, G.; Giordano, C.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Primary Adult Brain Tumors: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, G.; Zeppieri, M.; Gagliano, C.; Tel, A.; Tognetto, D.; Panciani, P.P.; Fontanella, M.M.; Ius, T.; Agosti, E. Advancing Glioblastoma Therapy with Surface-Modified Nanoparticles. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2025, 46, 5757–5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaroopan, D.; Lasocki, A. MRI-Based Deep Learning Techniques for the Prediction of Isocitrate Dehydrogenase and 1p/19q Status in Grade 2-4 Adult Gliomas. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 67, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikis, G.C.; Ioannidis, G.S.; Siakallis, I.; Nikiforaki, K.; Iv, M.; Vozlic, D.; Surlan-Popovic, K.S.; Wintermark, M.; Sotirios, B.S.; Kostas, M.K. Multicenter DSC-MRI-Based Radiomics Predict IDH Mutation in Gliomas. Cancers 2021, 13, 3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, D.; Liu, X.; Fan, X.; Wang, K.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, K.; Qian, T.; Jiang, T.; et al. Molecular subtyping of diffuse gliomas using magnetic resonance imaging: Comparison and correlation between radiomics and deep learning. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agosti, E.; Panciani, P.P.; Zeppieri, M.; De Maria, L.; Pasqualetti, F.; Tel, A.; Zanin, L.; Fontanella, M.M.; Ius, T. Tumor Microenvironment and Glioblastoma Cell Interplay as Promoters of Therapeutic Resistance. Biology 2023, 12, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, L.; Ponzio, F.; Cho, H.-H.; Skogen, K.; Tsougos, I.; Gasparini, M.; Zeppieri, M.; Ius, T.; Ugga, L.; Panciani, P.P.; et al. The Current Diagnostic Performance of MRI-Based Radiomics for Glioma Grading: A Meta-Analysis. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2024, 23, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mali, S.A.; Ibrahim, A.; Woodruff, H.C.; Andrearczyk, V.; Müller, H.; Primakov, S.; Salahuddin, Z.; Chatterjee, A.; Lambin, P. Making Radiomics More Reproducible across Scanner and Imaging Protocol Variations: A Review of Harmonization Methods. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Guo, Y.; Jin, Q. Radiomics and Its Feature Selection: A Review. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Xue, C.; Zhai, X.; Xiao, C.; Lu, T. Deep Learning and Habitat Radiomics for the Prediction of Glioma Pathology Using Multiparametric MRI: A Multicenter Study. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedhia, M.; Germano, I.M. The Evolving Landscape of Radiomics in Gliomas: Insights into Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Research Trends. Cancers 2025, 17, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Radiomics in Glioma: Emerging Trends and Challenges. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2025, 12, 460–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Manjila, S.; Sakla, N.; True, A.; Wardeh, A.H.; Beig, N.; Vaysberg, A.; Matthews, J.; Prasanna, P.; Spektor, V. Radiomics and Radiogenomics in Gliomas: A Contemporary Update. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.; Russo, C.; Di Ieva, A. Radiomics in Gliomas: Clinical Implications of Computational Modeling and Fractal-Based Analysis. Neuroradiology 2020, 62, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. The Clinical Implications and Interpretability of Computational Medical Imaging (Radiomics) in Brain Tumors. Insights Imaging 2025, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, D. Addressing the Current Challenges in the Clinical Application of AI-Based Radiomics for Cancer Imaging. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1674397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabeghi, P.; Zarand, P.; Zargham, S.; Golestany, B.; Shariat, A.; Chang, M.; Yang, E.; Rajagopalan, P.; Phung, D.C.; Gholamrezanezhad, A. Advances in Neuro-Oncological Imaging: An Update on Diagnostic Approach to Brain Tumors. Cancers 2024, 16, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Salle, G.; Tumminello, L.; Laino, M.E.; Shalaby, S.; Aghakhanyan, G.; Fanni, S.C.; Febi, M.; Shortrede, J.E.; Miccoli, M.; Faggioni, L.; et al. Accuracy of Radiomics in Predicting IDH Mutation Status in Diffuse Gliomas: A Bivariate Meta-Analysis. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, e220257. Available online: https://pubs.rsna.org/doi/10.1148/ryai.220257 (accessed on 30 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh, A.M.; Lomer, N.B.; Ashoobi, M.A.; Bathla, G.; Sotoudeh, H. MRI-Derived Radiomics and End-to-End Deep Learning Models for Predicting Glioma ATRX Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies. Clin. Imaging 2025, 119, 110386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.Y.C.; Pigott, L.E. Predicting IDH and ATRX mutations in gliomas from radiomic features with machine learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Radiol. 2024, 4, 1493824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahmadzadeh, A.M.; Broomand Lomer, N.; Ashoobi, M.A.; Elyassirad, D.; Gheiji, B.; Vatanparast, M.; Rostami, A.; Ali Abouei Mehrizi, M.; Tabari, A.; Bathla, G.; et al. MRI-derived deep learning models for predicting 1p/19q codeletion status in glioma patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies. Neuroradiology 2025, 67, 1667–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, S.; Hejazi, M.; Tabassum, M.; Di Ieva, A.; Mahdavifar, N.; Liu, S. Diagnostic performance of deep learning for predicting glioma isocitrate dehydrogenase and 1p/19q co-deletion in MRI: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A.P.; Liong, R.; Koppen, J.; Murthy, S.V.; Lasocki, A. Noninvasive Determination of IDH and 1p19q Status of Lower-Grade Gliomas Using MRI Radiomics: A Systematic Review. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambin, P.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Deist, T.M.; Peerlings, J.; de Jong, E.E.C.; van Timmeren, J.; Sanduleanu, S.; Larue, R.T.H.M.; Even, A.J.G.; Jochems, A.; et al. Radiomics: The Bridge between Medical Imaging and Personalized Medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwanenburg, A.; Vallières, M.; Abdalah, M.A.; Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Andrearczyk, V.; Apte, A.; Ashrafinia, S.; Bakas, S.; Beukinga, R.J.; Boellaard, R.; et al. The Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative: Standardized Quantitative Radiomics for High-Throughput Image-Based Phenotyping. Radiology 2020, 295, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang, A. Critical Evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for the Assessment of the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Thung, K.-H.; Liu, L.; Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; Shen, D. Multi-Label Inductive Matrix Completion for Joint MGMT and IDH1 Status Prediction for Glioma Patients. Med. Image Comput. Comput.-Assist. Interv. 2017, 10434, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, K.L.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lo, C.-M. Radiomic Model for Predicting Mutations in the Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Gene in Glioblastomas. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 45888–45897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, Z.; Xu, K.; Wang, K.; Fan, X.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, T. Radiomic Features Predict Ki-67 Expression Level and Survival in Lower Grade Gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 2017, 135, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Guo, Y.; Cao, W. Deep Learning Based Radiomics (DLR) and Its Usage in Noninvasive IDH1 Prediction for Low Grade Glioma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Lv, X.; Ju, X.; Shi, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z. Sparse Representation-Based Radiomics for the Diagnosis of Brain Tumors. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 37, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wu, Y.-X.; Xu, X.-P.; Li, B.-J.; Liu, Y.-X.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.-B. IDH Mutation Assessment of Glioma Using Texture Features of Multimodal MR Images. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2017: Computer-Aided Diagnosis, Orlando, FL, USA, 11–16 February 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Bai, H.X.; Zhou, H.; Su, C.; Bi, W.L.; Agbodza, E.; Kavouridis, V.K.; Senders, J.T.; Boaro, A.; Beers, A.; et al. Residual Convolutional Neural Network for the Determination of IDH Status in Low- and High-Grade Gliomas from MR Imaging. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.; Grinband, J.; Weinberg, B.D.; Bardis, M.; Khy, M.; Cadena, G.; Su, M.-Y.; Cha, S.; Filippi, C.G.; Bota, D.; et al. Deep-Learning Convolutional Neural Networks Accurately Classify Genetic Mutations in Gliomas. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Lu, J.; Thung, K.; Aibaidula, A.; Liu, L.; Chen, S.; Jin, L.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; et al. Multi-Label Nonlinear Matrix Completion With Transductive Multi-Task Feature Selection for Joint MGMT and IDH1 Status Prediction of Patient With High-Grade Gliomas. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 37, 1775–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.-C.; Bai, H.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liang, C.; Chen, Y.; Liang, D.; Zheng, H. Multiregional Radiomics Profiling from Multiparametric MRI: Identifying an Imaging Predictor of IDH1 Mutation Status in Glioblastoma. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 5999–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, K.; Qian, Z.; Wang, K.; Fan, X.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, T. MRI Features Can Predict EGFR Expression in Lower Grade Gliomas: A Voxel-Based Radiomic Analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, Z.; Xu, K.; Wang, K.; Fan, X.; Li, S.; Jiang, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. MRI Features Predict P53 Status in Lower-Grade Gliomas via a Machine-Learning Approach. NeuroImage Clin. 2018, 17, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Qian, Z.; Sun, Z.; Xu, K.; Wang, K.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; et al. Genotype Prediction of ATRX Mutation in Lower-Grade Gliomas Using an MRI Radiomics Signature. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 2960–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Zhang, R.; Liang, D.; Song, T.; Ai, T.; Xia, C.; Xia, L.; Wang, Y. Multimodal 3D DenseNet for IDH Genotype Prediction in Gliomas. Genes 2018, 9, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, P.; Lerche, C.; Bauer, E.K.; Steger, J.; Stoffels, G.; Blau, T.; Dunkl, V.; Kocher, M.; Viswanathan, S.; Filss, C.P.; et al. Predicting IDH Genotype in Gliomas Using FET PET Radiomics. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-F.; Hsu, F.-T.; Hsieh, K.L.-C.; Kao, Y.-C.J.; Cheng, S.-J.; Hsu, J.B.-K.; Tsai, P.-H.; Chen, R.-J.; Huang, C.-C.; Yen, Y.; et al. Machine Learning-Based Radiomics for Molecular Subtyping of Gliomas. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 4429–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaddad, A.; Daniel, P.; Sabri, S.; Desrosiers, C.; Abdulkarim, B. Integration of Radiomic and Multi-Omic Analyses Predicts Survival of Newly Diagnosed IDH1 Wild-Type Glioblastoma. Cancers 2019, 11, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuma, R.; Yanagisawa, T.; Kinoshita, M.; Shinozaki, T.; Arita, H.; Kawaguchi, A.; Takahashi, M.; Narita, Y.; Terakawa, Y.; Tsuyuguchi, N.; et al. Prediction of IDH and TERT Promoter Mutations in Low-Grade Glioma from Magnetic Resonance Images Using a Convolutional Neural Network. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Wang, S.; Miao, Y.; Shen, H.; Guo, Y.; Xie, L.; Shang, Y.; Dong, J.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; et al. MRI Texture Analysis Based on 3D Tumor Measurement Reflects the IDH1 Mutations in Gliomas—A Preliminary Study. Eur. J. Radiol. 2019, 112, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Wang, N.; Ravikumar, V.; Raghuram, D.R.; Li, J.; Patel, A.; Wendt, R.E.; Rao, G.; Rao, A. Prediction of 1p/19q Codeletion in Diffuse Glioma Patients Using Pre-Operative Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, M.A.; Ganeshan, B.; Barnes, A.; Bisdas, S.; Jaunmuktane, Z.; Brandner, S.; Endozo, R.; Groves, A.; Thust, S.C. Filtration-Histogram Based Magnetic Resonance Texture Analysis (MRTA) for Glioma IDH and 1p19q Genotyping. Eur. J. Radiol. 2019, 113, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Mu, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W.; Kong, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhou, X.; et al. A Non-Invasive Radiomic Method Using 18F-FDG PET Predicts Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Genotype and Prognosis in Patients With Glioma. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xu, K.; Fan, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Radiogenomic Analysis of PTEN Mutation in Glioblastoma Using Preoperative Multi-Parametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Neuroradiology 2019, 61, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalawade, S.; Murugesan, G.K.; Vejdani-Jahromi, M.; Fisicaro, R.A.; Bangalore Yogananda, C.G.; Wagner, B.; Mickey, B.; Maher, E.; Pinho, M.C.; Fei, B.; et al. Classification of Brain Tumor Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Status Using MRI and Deep Learning. J. Med. Imaging 2019, 6, 046003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhang, X.; Rui, W.; Pang, H.; Qiu, T.; Wang, J.; Xie, Q.; Jin, T.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; et al. Noninvasive Prediction of IDH1 Mutation and ATRX Expression Loss in Low-Grade Gliomas Using Multiparametric MR Radiomic Features. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI 2019, 49, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Xu, K.; Wang, K.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, T.; Liu, X. Radiogenomic Analysis of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Patients with Diffuse Gliomas. Cancer Imaging Off. Publ. Int. Cancer Imaging Soc. 2019, 19, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Yang, G.; Hao, X.; Gu, D.; Tan, Y.; Wang, X.; Dong, D.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; et al. A Multi-Sequence and Habitat-Based MRI Radiomics Signature for Preoperative Prediction of MGMT Promoter Methylation in Astrocytomas with Prognostic Implication. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alis, D.; Bagcilar, O.; Senli, Y.D.; Yergin, M.; Isler, C.; Kocer, N.; Islak, C.; Kizilkilic, O. Machine Learning-Based Quantitative Texture Analysis of Conventional MRI Combined with ADC Maps for Assessment of IDH1 Mutation in High-Grade Gliomas. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2020, 38, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; Cha, S. A Fully Automated Artificial Intelligence Method for Non-Invasive, Imaging-Based Identification of Genetic Alterations in Glioblastomas. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Nam, Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, J.; Ahn, K.-J.; Jang, J.; Shin, N.-Y.; Kim, B.-S.; Jeon, S.-S. IDH1 Mutation Prediction Using MR-Based Radiomics in Glioblastoma: Comparison between Manual and Fully Automated Deep Learning-Based Approach of Tumor Segmentation. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 128, 109031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chougule, T.; Shinde, S.; Santosh, V.; Saini, J.; Ingalhalikar, M. On Validating Multimodal MRI Based Stratification of IDH Genotype in High Grade Gliomas Using CNNs and Its Comparison to Radiomics. In Proceedings of the Radiomics and Radiogenomics in Neuro-Oncology; Mohy-ud-Din, H., Rathore, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Decuyper, M.; Bonte, S.; Deblaere, K.; Van Holen, R. Automated MRI Based Pipeline for Segmentation and Prediction of Grade, IDH Mutation and 1p19q Co-Deletion in Glioma. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2021, 88, 101831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, C.; Gu, I.Y.-H.; Jakola, A.S.; Yang, J. Deep Semi-Supervised Learning for Brain Tumor Classification. BMC Med. Imaging 2020, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubold, J.; Demircioglu, A.; Gratz, M.; Glas, M.; Wrede, K.; Sure, U.; Antoch, G.; Keyvani, K.; Nittka, M.; Kannengiesser, S.; et al. Non-Invasive Tumor Decoding and Phenotyping of Cerebral Gliomas Utilizing Multiparametric 18F-FET PET-MRI and MR Fingerprinting. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2020, 47, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.-M.; Weng, R.-C.; Cheng, S.-J.; Wang, H.-J.; Hsieh, K.L.-C. Computer-Aided Diagnosis of Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Genotypes in Glioblastomas from Radiomic Patterns. Medicine 2020, 99, e19123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, Y.; Maruyama, T.; Nitta, M.; Saito, T.; Tsuzuki, S.; Tamura, M.; Kusuda, K.; Fukuya, Y.; Asano, H.; Kawamata, T.; et al. Prediction of Lower-Grade Glioma Molecular Subtypes Using Deep Learning. J. Neurooncol. 2020, 146, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Feng, W.-H.; Duan, C.-F.; Liu, Y.-C.; Liu, J.-H.; Liu, X.-J. The Value of Enhanced MR Radiomics in Estimating the IDH1 Genotype in High-Grade Gliomas. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 4630218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, S.; Mohan, S.; Bakas, S.; Sako, C.; Badve, C.; Pati, S.; Singh, A.; Bounias, D.; Ngo, P.; Akbari, H.; et al. Multi-Institutional Noninvasive in Vivo Characterization of IDH, 1p/19q, and EGFRvIII in Glioma Using Neuro-Cancer Imaging Phenomics Toolkit (Neuro-CaPTk). Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2020, 2, iv22–iv34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Y.; Yang, C.; Kihira, S.; Tsankova, N.; Khan, F.; Hormigo, A.; Lai, A.; Cloughesy, T.; Nael, K. MRI Radiomic Features to Predict IDH1 Mutation Status in Gliomas: A Machine Learning Approach Using Gradient Tree Boosting. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Sun, H.; Chen, N.; Roberts, N.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Huang, X.; Gong, Q.; Yue, Q. A Radiomics-Clinical Nomogram for Preoperative Prediction of IDH1 Mutation in Primary Glioblastoma Multiforme. Clin. Radiol. 2020, 75, 963.e7–963.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudre, C.H.; Panovska-Griffiths, J.; Sanverdi, E.; Brandner, S.; Katsaros, V.K.; Stranjalis, G.; Pizzini, F.B.; Ghimenton, C.; Surlan-Popovic, K.; Avsenik, J.; et al. Machine Learning Assisted DSC-MRI Radiomics as a Tool for Glioma Classification by Grade and Mutation Status. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogananda, C.G.B.; Shah, B.R.; Yu, F.F.; Pinho, M.C.; Nalawade, S.S.; Murugesan, G.K.; Wagner, B.C.; Mickey, B.; Patel, T.R.; Fei, B.; et al. A Novel Fully Automated MRI-Based Deep-Learning Method for Classification of 1p/19q Co-Deletion Status in Brain Gliomas. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2020, 2, vdaa066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Sun, Z.; Fang, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, H.; et al. Preoperative Radiomics Analysis of 1p/19q Status in WHO Grade II Gliomas. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 616740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Fan, Z.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, H.; et al. Radiomics Features Predict Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Promoter Mutations in World Health Organization Grade II Gliomas via a Machine-Learning Approach. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 606741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-Y.; Wen, L.-H.; Wu, G.; Hu, M.-Z.; Zhang, C.-C.; Chen, F.; Zhao, J.-N. Comparison of Radiomics Analyses Based on Different Magnetic Resonance Imaging Sequences in Grading and Molecular Genomic Typing of Glioma. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2021, 45, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihira, S.; Tsankova, N.M.; Bauer, A.; Sakai, Y.; Mahmoudi, K.; Zubizarreta, N.; Houldsworth, J.; Khan, F.; Salamon, N.; Hormigo, A.; et al. Multiparametric MRI Texture Analysis in Prediction of Glioma Biomarker Status: Added Value of MR Diffusion. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2021, 3, vdab051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, L.; Napolitano, A.; Tagliente, E.; Dellepiane, F.; Lucignani, M.; Vidiri, A.; Ranazzi, G.; Stoppacciaro, A.; Moltoni, G.; Nicolai, M.; et al. Deep Learning Can Differentiate IDH-Mutant from IDH-Wild GBM. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Huo, J.; Li, B.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Ma, L. Predicting Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH) Mutation Status in Gliomas Using Multiparameter MRI Radiomics Features. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI 2021, 53, 1399–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santinha, J.; Matos, C.; Figueiredo, M.; Papanikolaou, N. Improving Performance and Generalizability in Radiogenomics: A Pilot Study for Prediction of IDH1/2 Mutation Status in Gliomas with Multicentric Data. J. Med. Imaging 2021, 8, 031905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, B.; An, C.; Kim, D.; Ahn, S.S.; Han, K.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, S.-G.; Chang, J.H.; Lee, S.-K. Radiomics-Based Prediction of Multiple Gene Alteration Incorporating Mutual Genetic Information in Glioblastoma and Grade 4 Astrocytoma, IDH-Mutant. J. Neurooncol. 2021, 155, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verduin, M.; Primakov, S.; Compter, I.; Woodruff, H.C.; van Kuijk, S.M.J.; Ramaekers, B.L.T.; te Dorsthorst, M.; Revenich, E.G.M.; ter Laan, M.; Pegge, S.A.H.; et al. Prognostic and Predictive Value of Integrated Qualitative and Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Analysis in Glioblastoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.; Rudie, J.D.; Rauschecker, A.M.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; Clarke, J.L.; Solomon, D.A.; Cha, S. Combining Radiomics and Deep Convolutional Neural Network Features from Preoperative MRI for Predicting Clinically Relevant Genetic Biomarkers in Glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2022, 4, vdac060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, R.; Fa, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Shao, G. ATRX Status in Patients with Gliomas: Radiomics Analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e30189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Rui, W.; Sheng, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Qiu, T.; Ren, Y. A Nomogram Strategy for Identifying the Subclassification of IDH Mutation and ATRX Expression Loss in Lower-Grade Gliomas. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 3187–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Ren, J.-X.; Yu, Z.-P.; Peng, Y.-D.; Yu, C.-W.; Deng, D.; Xie, Y.; He, Z.-Q.; Duan, H.; Wu, B.; et al. Predicting Glioblastoma Molecular Subtypes and Prognosis with a Multimodal Model Integrating Convolutional Neural Network, Radiomics, and Semantics. J. Neurosurg. 2023, 139, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wang, L.; Song, D.; Gao, C.; Jing, L.; Lu, Y.; Liu, D.; Man, W.; Yang, K.; Meng, Z.; et al. Multimodal-Based Machine Learning Strategy for Accurate and Non-Invasive Prediction of Intramedullary Glioma Grade and Mutation Status of Molecular Markers: A Retrospective Study. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, T.A.; Saraiva Junior, R.G.; Cassia, G.D.S.E.; Nascimento, F.A.D.O.; Carvalho, J.L.A.D. Classification of 1p/19q Status in Low-Grade Gliomas: Experiments with Radiomic Features and Ensemble-Based Machine Learning Methods. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2023, 66, e23230002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, W.; Zhang, S.; Shi, H.; Sheng, Y.; Zhu, F.; Yao, Y.; Chen, X.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Aili, A.; et al. Deep Learning-Assisted Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping as a Tool for Grading and Molecular Subtyping of Gliomas. Phenomics 2023, 3, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Jena, B.; Mohapatra, B.; Gupta, N.; Kalra, M.; Scartozzi, M.; Saba, L.; Suri, J.S. Fused Deep Learning Paradigm for the Prediction of O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase Genotype in Glioblastoma Patients: A Neuro-Oncological Investigation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 153, 106492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.C.; Gagnon-Bartsch, J.; Srinivasan, A.; Kim, M.M.; Noll, D.C.; Rao, A. Radiomic Features of Contralateral and Ipsilateral Hemispheres for Prediction of Glioma Genetic Markers. Neurosci. Inform. 2023, 3, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Xiao, X.; Gu, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Pan, C.; Zhang, P.; Ma, L.; Zhang, L.; et al. Diffusion MRI-Based Connectomics Features Improve the Noninvasive Prediction of H3K27M Mutation in Brainstem Gliomas. Radiother. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Ther. Radiol. Oncol. 2023, 186, 109789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pan, H.; Liu, Z.; Gao, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y.; Cao, X.; Kan, Y.; et al. Multicenter Clinical Radiomics-Integrated Model Based on [18F]FDG PET and Multi-Modal MRI Predict ATRX Mutation Status in IDH-Mutant Lower-Grade Gliomas. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.-X.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, A.-N.; Chen, Z.-F.; Wang, X.-Z.; Wang, X.-M.; Yuan, Z.-G. The Application Value of Support Vector Machine Model Based on Multimodal MRI in Predicting IDH-1mutation and Ki-67 Expression in Glioma. BMC Med. Imaging 2024, 24, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wang, C.; Zheng, J.; Liu, M.; Li, M.; Xu, H.; Dong, H. Image Omics Nomogram Based on Incoherent Motion Diffusion-Weighted Imaging in Voxels Predicts ATRX Gene Mutation Status of Brain Glioma Patients. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2024, 37, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Wen, M.; Gao, J.; Yang, J.; Kan, Y.; Yang, X.; Wen, Z.; et al. A Fusion Model Integrating Magnetic Resonance Imaging Radiomics and Deep Learning Features for Predicting Alpha-Thalassemia X-Linked Intellectual Disability Mutation Status in Isocitrate Dehydrogenase-Mutant High-Grade Astrocytoma: A Multicenter Study. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2024, 14, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Xiao, X.; Gu, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Liao, H. Combined Evaluation of T1 and Diffusion MRI Improves the Noninvasive Prediction of H3K27M Mutation in Brainstem Gliomas. In Proceedings of the 12th Asian-Pacific Conference on Medical and Biological Engineering, Suzhou, China, 18–21 May 2023; Wang, G., Yao, D., Gu, Z., Peng, Y., Tong, S., Liu, C., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Zhou, J.; Wu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Meng, N.; Wu, Q.; Jin, S.; Liu, H.; Li, P.; Wang, M. Assessment of MGMT Promoter Methylation Status in Glioblastoma Using Deep Learning Features from Multi-Sequence MRI of Intratumoral and Peritumoral Regions. Cancer Imaging 2024, 24, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, D.; Sun, H.; Kemp, G.J.; Chen, Y.; Tan, Q.; Yang, Y.; Gong, Q.; Yue, Q. Whole Brain Morphologic Features Improve the Predictive Accuracy of IDH Status and VEGF Expression Levels in Gliomas. Cereb. Cortex 2024, 34, bhae151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Yan, J.; Hao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, C.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Su, Y.; Peng, B.; et al. MRI Transformer Deep Learning and Radiomics for Predicting IDH Wild Type TERT Promoter Mutant Gliomas. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Peng, B.; Wang, Z.; Jin, X.; Niu, W.; Yang, X. Pre-Operative Prediction of High-Risk Molecular Subtypes of Glioma Based on Multimodal MRI Tumor Habitat Imaging. Cancer Plus 2025, 7, 025220038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Cohort Total (Training, Validation, Testing) (N) | MRI Sequences | Segmentation Method | Software | ML/DL Models | Molecular Pattern | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al., 2017 [35] | 47 | DWI | NA | NA | MIMC | MGMT, IDH | Accuracy 88.47%, 77.21% |

| Hsieh et al., 2017 [36] | 39 | T1 | Manual | OsiriX | Logistic regression | IDH | Accuracy 51%, 59%, 85% |

| Li et al., 2017 [37] | 117 (78, 39, 0) | T2 | Manual | MATLAB | ML | Ki-67 | AUC = 0.781, accuracy 83.3% and 88.6% |

| Li et al., 2017 [38] | 151 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Automatic | CNN | ROI-only CNN | IDH | AUC = 0.80–0.96 |

| Wu et al., 2018 [39] | 102 (67, 35) | T1, FLAIR | Manual | NA | Sparse representation | IDH | Accuracy 98.5%, 94.5% |

| Zhang et al., 2017 [40] | 152 | T1, T2, FLAIR | ROI | Histogram | NA | IDH | Accuracy 82% |

| Chang et al., 2018 [41] | 496 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Manual | Matrix User, 3D Slicer | 34-layer residual CNN with decision fusion | IDH | AUC = 0.90, 0.93, 0.94 |

| Chang et al., 2018 [42] | 259 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Automatic | FLIRT | Automatic segmentation with 2D CNN | IDH, 1p/19q | AUC = 0.91, AUC = 0.88 |

| Chen et al., 2018 [43] | 47 | T1 | NA | Custom pipeline | MNMC | MGMT, IDH | AUC = 0.787, 0.886 |

| Li et al., 2018 [44] | 225 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Manual, semi-automatic | Boruta | Random forest classifier | IDH | AUC = 0.96 |

| Li et al., 2018 [45] | 270 (200, 70, 0) | T2 | Manual | MRIcron + pipeline MATLAB | Logistic regression model | EGFR | Training AUC = 0.90, validation AUC = 0.95 |

| Li et al., 2018 [46] | 272 (180, 92, 0) | T2 | Manual | MATLAB | LASSO + SVM | p53 | Training AUC = 0.896, validation AUC = 0.763 |

| Li et al., 2018 [47] | 63, 32 | T2 | Manual | MRIcro | SVM, LASSO | ATRX | AUC = 0.94, 0.925 |

| Liang et al., 2018 [48] | 167 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Manual | M3D-DenseNet | Multi-channel ROI-only 3D DenseNet | IDH | AUC = 0.86 |

| Lohmann et al., 2018 [49] | 84 | PET | VOI | NA | Logistic regression | IDH | AUC = 0.79 |

| Lu et al., 2018 [50] | 214 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Manual | NA | NA | IDH, 1p/19q | AUC = 0.922–0.975 |

| Chaddad et al., 2019 [51] | 107 | T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | Manual | 3D Slicer | Random forest | ATRX | NA |

| Fukuma et al., 2019 [52] | 164 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Manual | VOI, MATLAB | Pretrained CNN (AlexNet) | IDH | 69.6% prediction accuracy |

| Han et al., 2019 [53] | 42 | T1, T2 | Manual | OmniKinetics | GLCM | IDH | AUC = 0.844, 0.848 |

| Kim et al., 2019 [54] | 143 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Manual | CNN | Textural, topological, and pre-trained CNN features | 1p/19q | AUC = 0.71 |

| Lewis et al., 2019 [55] | 97 | T1, T2 | Tumor segmentation | TexRAD | Logistic regression | IDH, 1p/19q | AUC = 0.98, 0.811 |

| Li et al., 2019 [56] | 127 | 18-FDG PET | Manual | Elastic net | SVM | IDH | AUC = 0.911, 0.900 |

| Li et al., 2019 [57] | NA | T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | Manual | NA | ML | PTEN | NA |

| Nalawade et al., 2019 [58] | 260 | T2 | NA | 2D DenseNet-161 CNN | ResNET-50, DenseNET-161, inception-v4 | IDH | AUC = 0.95, AUC = 0.86 |

| Ren et al., 2019 [59] | 36 | NA | Manual | NA | Machine learning | ATRX | AUC = 0.93 |

| Sun et al., 2019 [60] | 239 (160, 79, 0) | T1, T2, FLAIR | Manual | NA | mRMR + SVM | VEGF | AUC Training 0.741, Validation 0.702 |

| Wei et al., 2019 [61] | 105 | T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | Manual | MATLAB | ML | MGMT | Accuracy 86%, AUC 0.93 |

| Alis et al., 2020 [62] | 142 (96, 46, 0) | T1, T2 FLAIR, DWI | Manual | NA | Random forest classifier | IDH | Accuracy 86.94% |

| Calabrese et al., 2020 [63] | 190 | T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | Automated | dCNN | Random forest | ATRX | AUC = 0.97 |

| Choi et al., 2020 [64] | 136 | T2 | Manual, automatic | ROI | Machine learning classifier | IDH | AUC = 0.90, 0.86 |

| Chougule et al., 2020 [65] | 147 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Auto-encoder based automatic, manual | PyRadiomics 2.2.0 | 2D-CNN | IDH | NA |

| Decuyper et al., 2021 [66] | 628, 110 | T1, t1-CE, T2, FLAIR | 3D U-Net automatic segmentation | NA | 3D U-Net segmentation and 3D ROI extraction | IDH, 1p/19q | AUC = 0.86, AUC = 0.87 |

| Ge et al., 2020 [67] | NA | T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | CNN segmentation + 3D-2D consistency constraint | NA | Semi-supervised learning with 3D-2D consistent graph-based method and estimating labels of unlabelled data | IDH | 86.53% accuracy |

| Haubold et al., 2020 [68] | 42 | T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | Semi-automated | 3D Slicer | SVM | ATRX | AUC = 85.1% |

| Lo et al., 2020 [69] | 97 (69, 28) | T1 | Manual | In-house software | Random forest classifier | IDH | AUC = 0.872 |

| Matsui et al., 2020 [70] | 217 | T1, T2, FLAIR | NA | CNN | Deep learning model using multimodal data | IDH | 58.7% accuracy |

| Niu et al., 2020 [71] | 182 | T1 | Manual | A.K. software | LASSO | IDH | AUC = 0.86 |

| Rathore et al., 2020 [72] | 473 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Manual, semi-automated | NA | SVM | IDH, 1p/19q, EGFR | NA |

| Sakai et al., 2020 [73] | 100 | T1, FLAIR | VOI | In-house postprocessing | XGBoost, SMOTE | IDH | AUC = 0.97, 0.95 |

| Su et al., 2020 [74] | 414 | T1, FLAIR | Manual | LASSO | Logistic regression | IDH | AUC = 0.891 |

| Sudre et al., 2020 [75] | 333 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Manual | Haralick texture | Random forest | IDH | Accuracy 71% |

| Yogananda et al., 2020 [76] | 368 | T2 | Automatic | 3D-Dense-UNet | Fully automated CNN | 1p/19q | AUC = 0.953 |

| Fan et al., 2021 [77] | 157 | T1, T1-CE, T2 | Manual | MATLAB | Elastic Net + SVM | 1p/19q | AUC 0.8079, Accuracy 0–758 |

| Fang et al., 2020 [78] | 164 | T1, T1-CE, T2 | Manual | pipeline MATLAB | Elastic Net + SVM | TERT | AUC 0.8446, Accuracy 0.80 |

| Huang et al., 2021 [79] | 59 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Manual | NA | Logistic regression | IDH, MGMT | NA |

| Kihira et al., 2021 [80] | 111 (91, 20, 0) | T1, T1-CE, FLAIR | Manual | LASSO | Logistic regression | IDH, ATRX, MGMT, EGFR | AUC = 1.00, 0.99, 0.79, 0.77 |

| Pasquini et al., 2021 [81] | 100 | T1, T2, FLAIR | Bounding-box ROI | 4-block 2D CNN | 4-block 2D CNN | IDH | AUC = 0.83 |

| Peng et al., 2021 [82] | 105 | T1, T2 | Manual | VOI, LASSO | SVM | IDH | AUC = 0.770, 0.819, AUC = 0.747 |

| Santinha et al., 2021 [83] | 77 | T1, T2, FLAIR | NA | NA | LASSO | IDH | NA |

| Sohn et al., 2021 [84] | 418 | T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | Automated | A U-Net-based algorithm | Radiomics + Binary relevance | ATRX | AUC = 0.804, 0.842, 0.967 |

| Verduin et al., 2021 [85] | 185 (142, 46) | T1, T2 | VOI | VASARI | XGBoost | IDH, EGFR, MGMT | AUC = 0.695, 0.707, 0.667 |

| Calabrese et al., 2022 [86] | 396 | T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | Semi-automated | BraTS, ITK-SNAP | CNN, Random forest | ATRX | AUC = 0.97 |

| Meng et al., 2022 [87] | 123 | T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | Manual | Radcloud | SVM, LASSO | ATRX | AUC = 0.93, 0.84 |

| Wu et al., 2022 [88] | 76 | T1, T1-CE, FLAIR | Manual | MATLAB | Logistic regression | ATRX | C-index 0.863, 0.840 |

| Zhong et al., 2023 [89] | 329 | T1, T1-CE, T2 | Automated | BraTS toolkit | 3D ResNet50 + C3D | ATRX | AUC = 0.953 |

| Ma et al., 2023 [90] | 459 | T2 | Manual, automated | ITK-SNAP, Swin transformer model | XGBoost, Random forest | ATRX | AUC = 0.8431, 0.7622, 0.7954 |

| Medeiros et al., 2023 [91] | 261 | T2 | Manual ROI | NA | ML | 1p/19q | NA |

| Rui et al., 2023 [92] | 23 | NA | Manual | ITK-SNAP | CNN | ATRX | AUC = 0.78 |

| Saxena et al., 2023 [93] | 400 + 185 | T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | Subregions: ED/TC/ET | NA | Fused DL + ML (ResNet/EfficientNet + radiomiocs) | MGMT | AUC 0.75 |

| Wang et al., 2023 [94] | 82 | T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | Automated | BraTS | Random forest | ATRX | NA |

| Yang et al., 2023 [95] | 133 + 27 | T1, T1-CE, T2 | ROI + connectomics | NA | SVM + Relief/LASSO | H3K27M | AUC 0.91 |

| Zhang et al., 2023 [96] | 102 | T1, T2 | Semi-automated | 3D Slicer | Random forest | ATRX | AUC = 0.987, 0.975 |

| Liang et al., 2024 [97] | 309 | DWI | Manual ROI | 3D-Slicer | SVM | IDH, Ki-67 | AUC 0.97 |

| Lin et al., 2024 [98] | 85 (61, 24) | DWI | Manual | 3D Slicer | Radiomics + logistic regression monogram | ATRX | AUC = 0.97, 0.91 |

| Liu et al., 2024 [99] | 234 | T1-CE, FLAIR | Manual | 3D Slicer | PyRadiomics, ResNet34, Logistic regression | ATRX | AUC = 0.969, 0.956, 0.949 |

| Yang et al., 2024 [100] | NA | T1 | ROI + DWI features | NA | ML | H3K27M | NA |

| Yu et al., 2024 [101] | 356 | T1, T1-CE | NA | NA | Deep learning (CNN/Transformer) | MGMT | AUC 0.923 |

| Zhang et al., 2024 [102] | NA | T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR | Whole-brain morphometry | NA | Radiomics + morphology | IDH, VEGF | NA |

| Niu et al., 2025 [103] | 1185 | T1-CE, T2 FLAIR | VOI | Deep learning | 2D DL | IDH, TERT | AUC = 0.855–0.904 |

| Su et al., 2025 [104] | 204 | T1-CE, T2 | K-means habitat clustering | NA | SVM | IDH, EGFR | AUC = 0.943, 0.912 |

| Feature | Systematic/Focused Evaluations | Current State of Literature (n = 70) |

|---|---|---|

| Availability | Limited to a few comprehensive works | Abundant individual primary studies (2017–2025) |

| Biomarker Focus | Scarce for emerging markers (H3K27M, TERT, PTEN) | High concentration on IDH (66.2%) and ATRX (36.5%) |

| Methodology | Lack of standardized cross-study protocols | High Heterogeneity: Manual segmentation (70.3%), varied MRI sequences |

| Data Usage | Limited pooled effect size or meta-analysis | Large combined cohort (n = 10,324), mostly retrospective |

| Modeling | Few comparative benchmarks | Dominance of SVM (39.2%) and CNNs (27.0%) |

| Performance | Variable generalizability; limited external validation | High mean AUCs (Training: 0.892; Testing: 0.842) |

| Feature Category | Deep Learning-Based | Handcrafted Radiomics |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Extraction | Learned autonomously (Latent representations) | Predefined (Shape, First-order, Haralick/GLCM) |

| Interpretability | Lower (“Black box” nature of deep features) | Higher (Spatially and mathematically defined) |

| Common Models | CNNs (27.0%), Transformers (5.4%) | SVM (39.2%), Logistic Regression (14.9%) |

| Segmentation | Increasingly Automated/U-Net (17.6%) | Predominantly Manual (70.3%) |

| Performance (IDH) | AUC 0.88–0.99 (e.g., 3D Dense-UNet) | AUC 0.80–0.92 |

| Integration | End-to-end learning (Radiomics-DL fusion) | Requires explicit feature selection (e.g., LASSO) |

| Author, Year | Method | RQS (36) | IBSI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al., 2017 [35] | Handcrafted | 13 | 43 |

| Hsieh et al., 2017 [36] | Handcrafted | 15 | 71 |

| Li et al., 2017 [37] | Deep Learning | 14 | 29 |

| Li et al., 2017 [38] | Handcrafted | 16 | 86 |

| Wu et al., 2018 [39] | Handcrafted | 14 | 57 |

| Zhang et al., 2017 [40] | Handcrafted | 15 | 71 |

| Chang et al., 2018 [41] | Deep Learning | 16 | 29 |

| Chang et al., 2018 [42] | Handcrafted | 17 | 86 |

| Chen et al., 2018 [43] | Multimodal | 18 | 57 |

| Li et al., 2018 [44] | Handcrafted | 14 | 71 |

| Li et al., 2018 [45] | Deep Learning | 15 | 29 |

| Li et al., 2018 [46] | Handcrafted | 16 | 57 |

| Li et al., 2018 [47] | Combined | 19 | 86 |

| Liang et al., 2018 [48] | Handcrafted | 15 | 71 |

| Lohmann et al., 2018 [49] | Deep Learning | 16 | 43 |

| Lu et al., 2018 [50] | Handcrafted | 14 | 57 |

| Chaddad et al., 2019 [51] | Multimodal | 20 | 86 |

| Fukuma et al., 2019 [52] | Handcrafted | 15 | 71 |

| Han et al., 2019 [53] | Deep Learning | 17 | 29 |

| Kim et al., 2019 [54] | Deep Learning | 15 | 43 |

| Lewis et al., 2019 [55] | Handcrafted | 14 | 57 |

| Li et al., 2019 [56] | Handcrafted | 16 | 71 |

| Li et al., 2019 [57] | Deep Learning | 17 | 29 |

| Nalawade et al., 2019 [58] | Handcrafted | 15 | 86 |

| Ren et al., 2019 [59] | Deep Learning | 16 | 43 |

| Sun et al., 2019 [60] | Handcrafted | 14 | 71 |

| Wei et al., 2019 [61] | Handcrafted | 15 | 86 |

| Alis et al., 2020 [62] | Deep Learning | 17 | 43 |

| Calabrese et al., 2020 [63] | Multimodal | 21 | 100 |

| Choi et al., 2020 [64] | Handcrafted | 16 | 71 |

| Chougule et al., 2020 [65] | Deep Learning | 15 | 29 |

| Decuyper et al., 2021 [66] | Combined | 18 | 86 |

| Ge et al., 2020 [67] | Deep Learning | 17 | 43 |

| Haubold et al., 2020 [68] | Handcrafted | 16 | 86 |

| Lo et al., 2020 [69] | Handcrafted | 15 | 71 |

| Matsui et al., 2020 [70] | Deep Learning | 16 | 29 |

| Niu et al., 2020 [71] | Handcrafted | 17 | 57 |

| Rathore et al., 2020 [72] | Combined | 20 | 86 |

| Sakai et al., 2020 [73] | Handcrafted | 15 | 71 |

| Su et al., 2020 [74] | Deep Learning | 16 | 43 |

| Sudre et al., 2020 [75] | Multimodal | 19 | 86 |

| Yogananda et al., 2020 [76] | Deep Learning | 17 | 29 |

| Fan et al., 2021 [77] | Handcrafted | 16 | 86 |

| Fang et al., 2020 [78] | Deep Learning | 17 | 43 |

| Huang et al., 2021 [79] | Handcrafted | 15 | 71 |

| Kihira et al., 2021 [80] | Multimodal | 19 | 86 |

| Pasquini et al., 2021 [81] | Handcrafted | 16 | 71 |

| Peng et al., 2021 [82] | Deep Learning | 17 | 29 |

| Santinha et al., 2021 [83] | Handcrafted | 15 | 86 |

| Sohn et al., 2021 [84] | Deep Learning | 16 | 43 |

| Verduin et al., 2021 [85] | Multimodal | 19 | 86 |

| Calabrese et al., 2022 [86] | Combined | 22 | 100 |

| Meng et al., 2022 [87] | Deep Learning | 18 | 43 |

| Wu et al., 2022 [88] | Handcrafted | 17 | 86 |

| Zhong et al., 2023 [89] | Deep Learning | 18 | 29 |

| Ma et al., 2023 [90] | Handcrafted | 17 | 71 |

| Medeiros et al., 2023 [91] | Deep Learning | 18 | 43 |

| Rui et al., 2023 [92] | Handcrafted | 19 | 57 |

| Saxena et al., 2023 [93] | Multimodal | 21 | 86 |

| Wang et al., 2023 [94] | Deep Learning | 18 | 29 |

| Yang et al., 2023 [95] | Handcrafted | 17 | 71 |

| Zhang et al., 2023 [96] | Combined | 22 | 100 |

| Liang et al., 2024 [97] | Deep Learning | 19 | 43 |

| Lin et al., 2024 [98] | Handcrafted | 18 | 71 |

| Liu et al., 2024 [99] | Multimodal | 23 | 86 |

| Yang et al., 2024 [100] | Deep Learning | 19 | 43 |

| Yu et al., 2024 [101] | Handcrafted | 18 | 71 |

| Zhang et al., 2024 [102] | Combined | 24 | 100 |

| Niu et al., 2025 [103] | Multimodal | 23 | 86 |

| Su et al., 2025 [104] | Combined | 25 | 100 |

| Author, Year | Selection (4) | Comparability (2) | Outcome (3) | Total Score | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al., 2017 [35] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | High |

| Hsieh et al., 2017 [36] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Li et al., 2017 [37] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Li et al., 2017 [38] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Wu et al., 2018 [39] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Zhang et al., 2017 [40] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Chang et al., 2018 [41] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | High |

| Chang et al., 2018 [42] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Chen et al., 2018 [43] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Li et al., 2018 [44] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | High |

| Li et al., 2018 [45] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Li et al., 2018 [46] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | High |

| Li et al., 2018 [47] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Liang et al., 2018 [48] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Lohmann et al., 2018 [49] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Lu et al., 2018 [50] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Chaddad et al., 2019 [51] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Fukuma et al., 2019 [52] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Han et al., 2019 [53] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Kim et al., 2019 [54] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Lewis et al., 2019 [55] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Li et al., 2019 [56] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Li et al., 2019 [57] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Nalawade et al., 2019 [58] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Ren et al., 2019 [59] | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | High |

| Sun et al., 2019 [60] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Wei et al., 2019 [61] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Alis et al., 2020 [62] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | High |

| Calabrese et al., 2020 [63] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Choi et al., 2020 [64] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Chougule et al., 2020 [65] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Decuyper et al., 2021 [66] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Ge et al., 2020 [67] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Haubold et al., 2020 [68] | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | High |

| Lo et al., 2020 [69] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Matsui et al., 2020 [70] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Niu et al., 2020 [71] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Rathore et al., 2020 [72] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | High |

| Sakai et al., 2020 [73] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Su et al., 2020 [74] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Sudre et al., 2020 [75] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Yogananda et al., 2020 [76] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Fan et al., 2021 [77] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Fang et al., 2020 [78] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Huang et al., 2021 [79] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Kihira et al., 2021 [80] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Pasquini et al., 2021 [81] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Peng et al., 2021 [82] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Santinha et al., 2021 [83] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Sohn et al., 2021 [84] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Verduin et al., 2021 [85] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Calabrese et al., 2022 [86] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Meng et al., 2022 [87] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Wu et al., 2022 [88] | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | High |

| Zhong et al., 2023 [89] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Ma et al., 2023 [90] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Medeiros et al., 2023 [91] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Rui et al., 2023 [92] | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | High |

| Saxena et al., 2023 [93] | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | High |

| Wang et al., 2023 [94] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Yang et al., 2023 [95] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Zhang et al., 2023 [96] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Liang et al., 2024 [97] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Lin et al., 2024 [98] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Liu et al., 2024 [99] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Yang et al., 2024 [100] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | High |

| Yu et al., 2024 [101] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Zhang et al., 2024 [102] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Niu et al., 2025 [103] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Su et al., 2025 [104] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | High |

| Critical Domain | Evidence from Literature | Technical/Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Methodological Rigor | High NOS (7–9) and RQS | High reporting quality does not equate to clinical validity or biological relevance. |

| Model Performance | Training AUC (0.892) vs. Testing AUC (0.842) | Performance drops suggest overfitting or data leakage in retrospective cohorts. |

| Algorithmic Trust | DL/CNNs (27.0%) yield higher AUC (up to 0.99) | The “Black Box” nature limits clinical trust compared to interpretable handcrafted features. |

| Standardization | 70.3% prevalence of manual segmentation | Significant heterogeneity hinders the reproducibility of results across different centers. |

| Biomarker Scope | High focus on IDH (66.2%) and ATRX (36.5%) | Neglect of emerging markers (H3K27M, TERT) delays comprehensive clinical adoption. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Agosti, E.; Mapelli, K.; Grimod, G.; Piazza, A.; Fontanella, M.M.; Panciani, P.P. MRI-Based Radiomics for Non-Invasive Prediction of Molecular Biomarkers in Gliomas. Cancers 2026, 18, 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030491

Agosti E, Mapelli K, Grimod G, Piazza A, Fontanella MM, Panciani PP. MRI-Based Radiomics for Non-Invasive Prediction of Molecular Biomarkers in Gliomas. Cancers. 2026; 18(3):491. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030491

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgosti, Edoardo, Karen Mapelli, Gianluca Grimod, Amedeo Piazza, Marco Maria Fontanella, and Pier Paolo Panciani. 2026. "MRI-Based Radiomics for Non-Invasive Prediction of Molecular Biomarkers in Gliomas" Cancers 18, no. 3: 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030491

APA StyleAgosti, E., Mapelli, K., Grimod, G., Piazza, A., Fontanella, M. M., & Panciani, P. P. (2026). MRI-Based Radiomics for Non-Invasive Prediction of Molecular Biomarkers in Gliomas. Cancers, 18(3), 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030491