Leukocyte Telomere Length Variants Are Independently Associated with Survival of Patients with Colorectal Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Blood Sample Collection

2.2. DNA Extraction and Telomere Length Measurement

2.3. Genotyping Methods

2.4. Outcome Variables

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Relationship of Telomere Length with Age, Sex and Disease Stage

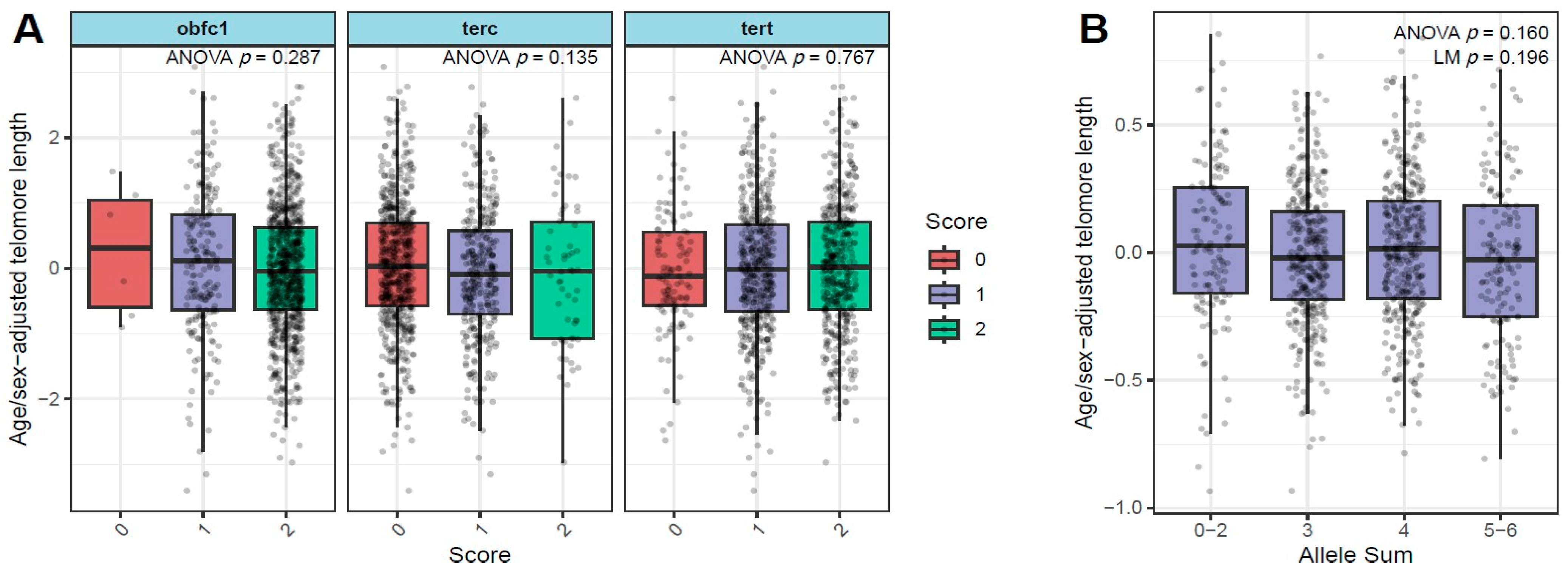

3.2. Relationship of Age/Sex-Adjusted Telomere Length with SNPS in TERT, TERC, and OBFC1 Genes

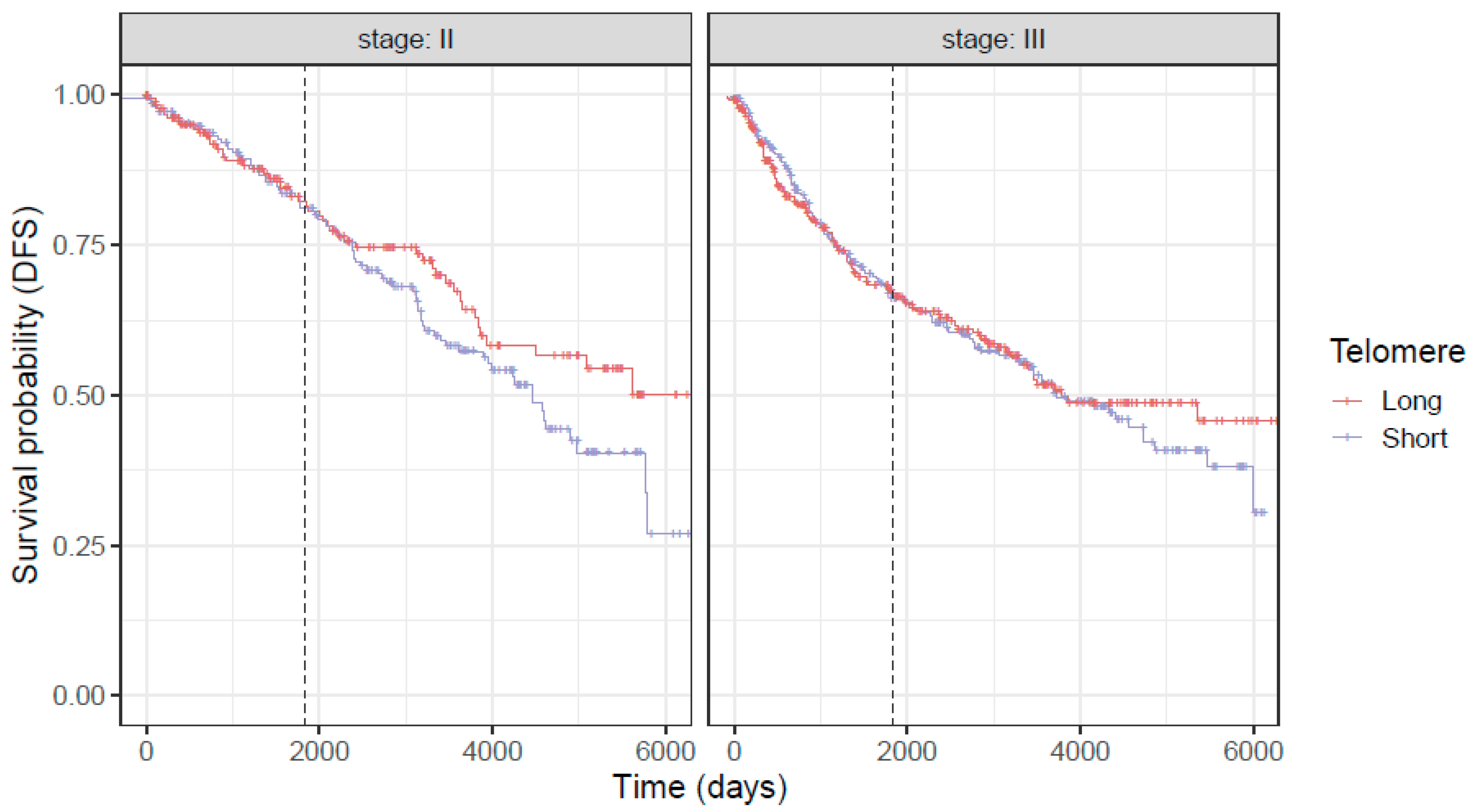

3.3. Associations of Telomere Length with Overall Survival (OS) and Disease-Free Survival (DFS) in Combined Stage 2 and 3 Population of CRC Patients

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfro, L.A.; Grothey, A.; Xue, Y.; Saltz, L.B.; Andre, T.; Twelves, C.; Labianca, R.; Allegra, C.J.; Alberts, S.R.; Loprinzi, C.L.; et al. ACCENT-based web calculators to predict recurrence and overall survival in stage III colon cancer. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, M.R.; Landmann, R.G.; Kattan, M.W.; Gonen, M.; Shia, J.; Chou, J.; Paty, P.B.; Guillem, J.G.; Temple, L.K.; Schrag, D.; et al. Individualized prediction of colon cancer recurrence using a nomogram. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, F.L.; Stewart, A.K.; Norton, H.J. A new TNM staging strategy for node-positive (stage III) colon cancer: An analysis of 50,042 patients. Ann. Surg. 2002, 236, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.H. Carcinoembryonic antigen. Ann. Intern. Med. 1986, 104, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Raghav, K.; Lieu, C.; Jiang, Z.; Eng, C.; Vauthey, J.; Chang, G.; Qiao, W.; Morris, J.; Hong, D.; et al. Cytokine profile and prognostic significance of high neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazaki, J.; Katsumata, K.; Kasahara, K.; Tago, T.; Wada, T.; Kuwabara, H.; Enomoto, M.; Ishizaki, T.; Nagakawa, Y.; Tsuchida, A. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a prognostic factor for colon cancer: A propensity score analysis. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, S.; Dai, W.; Wang, H.; Lan, X.; Ma, C.; Su, Z.; Xiang, W.; Han, L.; Luo, W.; Zhang, L.; et al. Early detection and prognosis prediction for colorectal cancer by circulating tumour DNA methylation haplotypes: A multicentre cohort study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 55, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gào, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Jansen, L.; Alwers, E.; Bewerunge-Hudler, M.; Schick, M.; Chang-Claude, J.; Hoffmeister, M.; Brenner, H. DNA methylation-based estimates of circulating leukocyte composition for predicting colorectal cancer survival: A prospective cohort study. Cancers 2021, 13, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Wen, Z.; Lai, Y.; Kamila, K.; Gao, J.; Xu, W.-y.; Gong, C.; Chen, F.; Shi, L.; et al. Genome wide identification of novel DNA methylation driven prognostic markers in colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yang, L.; Men, F.; Yu, J.; Sun, S.; Li, C.; Ma, X.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Tian, J. Early Diagnosis and Prognostic Prediction of Colorectal Cancer through Plasma Methylation Regions. medRxiv 2024. medRxiv:2028.24317652. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Huang, C.; Xu, L.; Tong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, S.; Fu, Z. Integrative genome-wide aberrant DNA methylation and transcriptome analysis identifies diagnostic markers for colorectal cancer. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 2179–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhao, H.; Hu, H.; Shang, H.; Wang, H.; Yao, Z.; Huang, J.; Lv, H.; Xu, W.; Wang, J.; et al. Circulating DNA methylation-based diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, J.G. Beginning of the end: Origins of the telomere concept. Telomeres 1995, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, C.B.; Futcher, A.B.; Greider, C.W. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 1990, 345, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, Y.; Wardhana, A.; Watkins, J.; Wulaningsih, W. Cigarette smoking and telomere length: A systematic review of 84 studies and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welendorf, C.; Nicoletti, C.F.; de Souza Pinhel, M.A.; Noronha, N.Y.; de Paula, B.M.F.; Nonino, C.B. Obesity, weight loss, and influence on telomere length: New insights for personalized nutrition. Nutrition 2019, 66, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutte, N.S.; Malouff, J.M. The relationship between perceived stress and telomere length: A meta-analysis. Stress Health 2016, 32, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, M.; Bann, D.; Wiley, L.; Cooper, R.; Hardy, R.; Nitsch, D.; Martin-Ruiz, C.; Shiels, P.; Sayer, A.A.; Barbieri, M.; et al. Gender and telomere length: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 51, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiè, S.; Canudas, S.; Muralidharan, J.; García-Gavilán, J.; Bulló, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Impact of nutrition on telomere health: Systematic review of observational cohort studies and randomized clinical trials. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 576–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazidi, M.; Michos, E.D.; Banach, M. The association of telomere length and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in US adults: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch. Med. Sci. 2017, 13, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Félix, N.Q.; Tornquist, L.; Sehn, A.P.; D’avila, H.F.; Todendi, P.F.; de Moura Valim, A.R.; Reuter, C.P. The association of telomere length with body mass index and immunological factors differs according to physical activity practice among children and adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wei, S.; Liu, Z.; Pooley, K.A.; Dunning, A.M.; Svenson, U.; Roos, G.; Hosgood, H.D., III; Shen, M. Shortened telomere length is associated with increased risk of cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzensen, I.M.; Mirabello, L.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Savage, S.A. The association of telomere length and cancer: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2011, 20, 1238–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachuri, L.; Latifovic, L.; Liu, G.; Hung, R.J. Systematic review of genetic variation in chromosome 5p15. 33 and telomere length as predictive and prognostic biomarkers for lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 1537–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, C.L.; Schwartz, K.; Ruterbusch, J.J.; Shuch, B.; Graubard, B.I.; Lan, Q.; Cawthon, R.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Chow, W.-H.; Rothman, N.; et al. Leukocyte telomere length and renal cell carcinoma survival in two studies. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Modica, F.; Guarrera, S.; Fiorito, G.; Pardini, B.; Viberti, C.; Allione, A.; Critelli, R.; Bosio, A.; Casetta, G.; et al. Shorter leukocyte telomere length is independently associated with poor survival in patients with bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 2439–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Cai, Q.; Qu, S.; Chow, W.-H.; Wen, W.; Xiang, Y.-B.; Wu, J.; Rothman, N.; Yang, G.; Shu, X.-O.; et al. Association of leukocyte telomere length with colorectal cancer risk: Nested case–control findings from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 1807–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, R.Y.; Castonguay, A.J.; Barton, N.S.; Buring, J.E. Mean telomere length and risk of incident colorectal carcinoma: A prospective, nested case-control approach. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 2280–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.; Beggs, A.; Carvajal-Carmona, L.; Farrington, S.; Tenesa, A.; Walker, M.; Howarth, K.; Ballereau, S.; Hodgson, S.; Zauber, A.; et al. TERC polymorphisms are associated both with susceptibility to colorectal cancer and with longer telomeres. Gut 2012, 61, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wan, S.; Hann, H.-W.; Myers, R.E.; Hann, R.S.; Au, J.; Chen, B.; Xing, J.; Yang, H. Relative telomere length: A novel non-invasive biomarker for the risk of non-cirrhotic hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Neuhausen, S.L.; Hunt, S.C.; Kimura, M.; Hwang, S.-J.; Chen, W.; Bis, J.C.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Smith, E.; Johnson, A.D.; et al. Genome-wide association identifies OBFC1 as a locus involved in human leukocyte telomere biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9293–9298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangino, M.; Hwang, S.-J.; Spector, T.D.; Hunt, S.C.; Kimura, M.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Christiansen, L.; Petersen, I.; Elbers, C.C.; Harris, T.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis points to CTC1 and ZNF676 as genes regulating telomere homeostasis in humans. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 5385–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rode, L.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Bojesen, S.E. Peripheral blood leukocyte telomere length and mortality among 64 637 individuals from the general population. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, djv074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawthon, R.M. Telomere length measurement by a novel monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qu, F.; He, X.; Bao, G.; Liu, X.; Wan, S.; Xing, J. Short leukocyte telomere length predicts poor prognosis and indicates altered immune functions in colorectal cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauleck, S.; Sinnott, J.A.; Zheng, Y.-L.; Gadalla, S.M.; Viskochil, R.; Haaland, B.; Cawthon, R.M.; Hoffmeister, A.; Hardikar, S. Association of telomere length with colorectal cancer risk and prognosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauleck, S.; Gigic, B.; Cawthon, R.M.; Ose, J.; Peoples, A.R.; Warby, C.A.; Sinnott, J.A.; Lin, T.; Boehm, J.; Schrotz-King, P.; et al. Association of circulating leukocyte telomere length with survival in patients with colorectal cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenson, U.; Öberg, Å.; Stenling, R.; Palmqvist, R.; Roos, G. Telomere length in peripheral leukocytes is associated with immune cell tumor infiltration and prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 10877–10882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Ding, T.; Wei, L.; Cao, S.; Yang, L. Shorter telomere length of T-cells in peripheral blood of patients with lung cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 2675–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, B.; Xiong, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S. Shorter telomere length increases the risk of lymphocyte immunodeficiency: A Mendelian randomization study. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanta, K.; Nakayama, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Ishibashi, T.; Yamashita, H.; Sato, S.; Sasamori, H.; Sawada, K.; Kurose, S.; Mahmud, H.M.; et al. Prognostic value of peripheral blood lymphocyte telomere length in gynecologic malignant tumors. Cancers 2020, 12, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, J.; Wentzensen, I.M.; Savage, S.A.; De Vivo, I. Epidemiologic evidence for a role of telomere 533 dysfunction in cancer etiology. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2012, 730, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mathon, N.F.; Lloyd, A.C. Cell senescence and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greider, C.W. Telomerase activity, cell proliferation, and cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez Roux, A.V.; Ranjit, N.; Jenny, N.S.; Shea, S.; Cushman, M.; Fitzpatrick, A.; Seeman, T. Race/ethnicity and telomere length in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Aging Cell 2009, 8, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drury, S.S.; Esteves, K.; Hatch, V.; Woodbury, M.; Borne, S.; Adamski, A.; Theall, K.P. Setting the trajectory: Racial disparities in newborn telomere length. J. Pediatr. 2015, 166, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordfjäll, K.; Svenson, U.; Norrback, K.-F.; Adolfsson, R.; Lenner, P.; Roos, G. The individual blood cell telomere attrition rate is telomere length dependent. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient Characteristics | Stage 2 (N = 402) | Stage 3 (N = 605) | Total (N = 1007) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | 0.106 | |||

| Female | 176 (43.8%) | 234 (38.7%) | 410 (40.7%) | |

| Male | 226 (56.2%) | 371 (61.3%) | 597 (59.3%) | |

| Age at Dx | <0.0001 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 65.4 (13.51) | 60.4 (13.61) | 62.4 (13.78) | |

| Median | 67.0 | 61.0 | 64.0 | |

| Range | 17.0, 93.0 | 21.0, 98.0 | 17.0, 98.0 | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.307 | |||

| Asian | 1 (0.2%) | 5 (0.8%) | 6 (0.6%) | |

| Black | 4 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.4%) | |

| Other | 6 (1.5%) | 9 (1.5%) | 15 (1.5%) | |

| Unknown | 18 (4.5%) | 33 (5.5%) | 51 (5.1%) | |

| White | 373 (92.8%) | 558 (92.2%) | 931 (92.5%) | |

| Status death, n (%) | 0.462 | |||

| No | 278 (69.2%) | 405 (66.9%) | 683 (67.8%) | |

| Yes | 124 (30.8%) | 200 (33.1%) | 324 (32.2%) | |

| Allele group, n (%) | 0.310 | |||

| 0–2 | 50 (12.4%) | 81 (13.4%) | 131 (13.0%) | |

| 3 | 131 (32.6%) | 215 (35.5%) | 346 (34.4%) | |

| 4 | 163 (40.5%) | 210 (34.7%) | 373 (37.0%) | |

| 5–6 | 58 (14.4%) | 99 (16.4%) | 157 (15.6%) |

| Overall Survival Model | Disease-Free Survival Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | Log Hazard Ratio | p-Value | Log Hazard Ratio | p-Value |

| Genotype | ||||

| TERT | −0.00827 | 0.920 | 0.0198 | 0.797 |

| TERC | −0.237 | 0.017 | −0.208 | 0.023 |

| OBFC1 | −0.314 | 0.016 | −0.207 | 0.093 |

| Male sex | 0.284 | 0.015 | 0.192 | 0.077 |

| Age | 0.0531 | <2 × 10−16 | 0.0383 | <2 × 10−16 |

| Stage 3 | 0.462 | 8.34 × 10−5 | 0.531 | 1.77 × 10−6 |

| Sex/Age-adjusted telomere length | −0.550 | 0.009 | −0.386 | 0.044 |

| Overall Survival Model | Disease-Free Survival Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | Log Hazard Ratio | p-Value | Log Hazard Ratio | p-Value |

| Genotype | ||||

| TERT | −0.0333 | 0.805 | 0.0201 | 0.878 |

| TERC | −0.330 | 0.059 | −0.359 | 0.033 |

| OBFC1 | −0.547 | 0.015 | −0.403 | 0.069 |

| Male sex | 0.407 | 0.029 | 0.389 | 0.031 |

| Age | 0.0610 | 1.03 × 10−10 | 0.0496 | 1.33 × 10−8 |

| Sex/Age-adjusted telomere length | −0.794 | 0.017 | −0.758 | 0.018 |

| Overall Survival Model | Disease-Free Survival Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | Log Hazard Ratio | p-Value | Log Hazard Ratio | p-Value |

| Genotype | ||||

| TERT | 0.0119 | 0.909 | 0.0311 | 0.748 |

| TERC | −0.179 | 0.138 | −0.130 | 0.236 |

| OBFC1 | −0.223 | 0.172 | −0.161 | 0.281 |

| Male sex | 0.208 | 0.165 | 0.0926 | 0.497 |

| Age | 0.0488 | 5.22 × 10−15 | 0.0325 | 1.2 × 10−9 |

| Sex/Age-adjusted telomere length | −0.429 | 0.111 | −0.225 | 0.349 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sarkar, G.; Chen, J.; Sood, S.; Fischer, K.; Kossick, K.; Schupack, D.; Graham, R.; Druliner, B.; Heydari, Z.; Helgeson, L.; et al. Leukocyte Telomere Length Variants Are Independently Associated with Survival of Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2026, 18, 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030490

Sarkar G, Chen J, Sood S, Fischer K, Kossick K, Schupack D, Graham R, Druliner B, Heydari Z, Helgeson L, et al. Leukocyte Telomere Length Variants Are Independently Associated with Survival of Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancers. 2026; 18(3):490. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030490

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarkar, Gobinda, Jun Chen, Shubham Sood, Karen Fischer, Kim Kossick, Daniel Schupack, Rondell Graham, Brooke Druliner, Zahra Heydari, Lauren Helgeson, and et al. 2026. "Leukocyte Telomere Length Variants Are Independently Associated with Survival of Patients with Colorectal Cancer" Cancers 18, no. 3: 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030490

APA StyleSarkar, G., Chen, J., Sood, S., Fischer, K., Kossick, K., Schupack, D., Graham, R., Druliner, B., Heydari, Z., Helgeson, L., Cruz Garcia, E., Cawthon, R., & Boardman, L. (2026). Leukocyte Telomere Length Variants Are Independently Associated with Survival of Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancers, 18(3), 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18030490