Clinical Behavior of Aggressive Variants of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Retrospective Case–Control Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

| Characteristics | Value (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 80 |

| Rare variant pathology | |

| Tall cell | 7 (8.8%) |

| Diffuse sclerosing | 5 (6.3%) |

| Columnar cell | 2 (2.5%) |

| Hobnail | 1 (1.3%) |

| Solid | 40 (50%) |

| Oncocytic | 14 (17.5%) |

| Warthin-like | 11 (13.8%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 19 (23.8%) |

| Female | 61 (76.3%) |

| Age, years (mean ± sd) | 51.7 ± 15.9 |

| FNAB | |

| Bethesda I | 0 |

| Bethesda II | 24 (30%) |

| Bethesda III/IV | 23 (28.7%) |

| Bethesda V | 5 (6.3%) |

| Bethesda VI | 7 (8.8%) |

| Not performed | 21 (26.3%) |

| Procedure | |

| Total thyroidectomy | 48 (60%) |

| Staged thyroidectomy | 4 (5%) |

| Near-total thyroidectomy | 6 (7.5%) |

| Thyroid lobectomy | 13 (16.3%) |

| Thyroidectomy with neck dissection | 9 (11.3%) |

| Primary tumor size, mm (mean ± sd) | 32.38 ± 30.42 |

| Clinicopathological characteristics | |

| Capsular invasion | 31 (38.8%) |

| Vascular invasion | 17 (21.3%) |

| LN metastases | 14 (17.5%) |

| Microscopic ETE | 16 (20%) |

| Gross ETE | 9 (11.3%) |

| Multifocal presentation | 31 (38.8%) |

| Bilateral presentation | 26 (32.5%) |

| Tumor recurrence | 8 (10%) |

| RAI treatment | 31 (38.8%) |

| Deaths | 6 (7.5%) |

| Cancer-specific deaths | 4 (5%) |

3.1. Clinicopathological Features Among the Four Subgroups

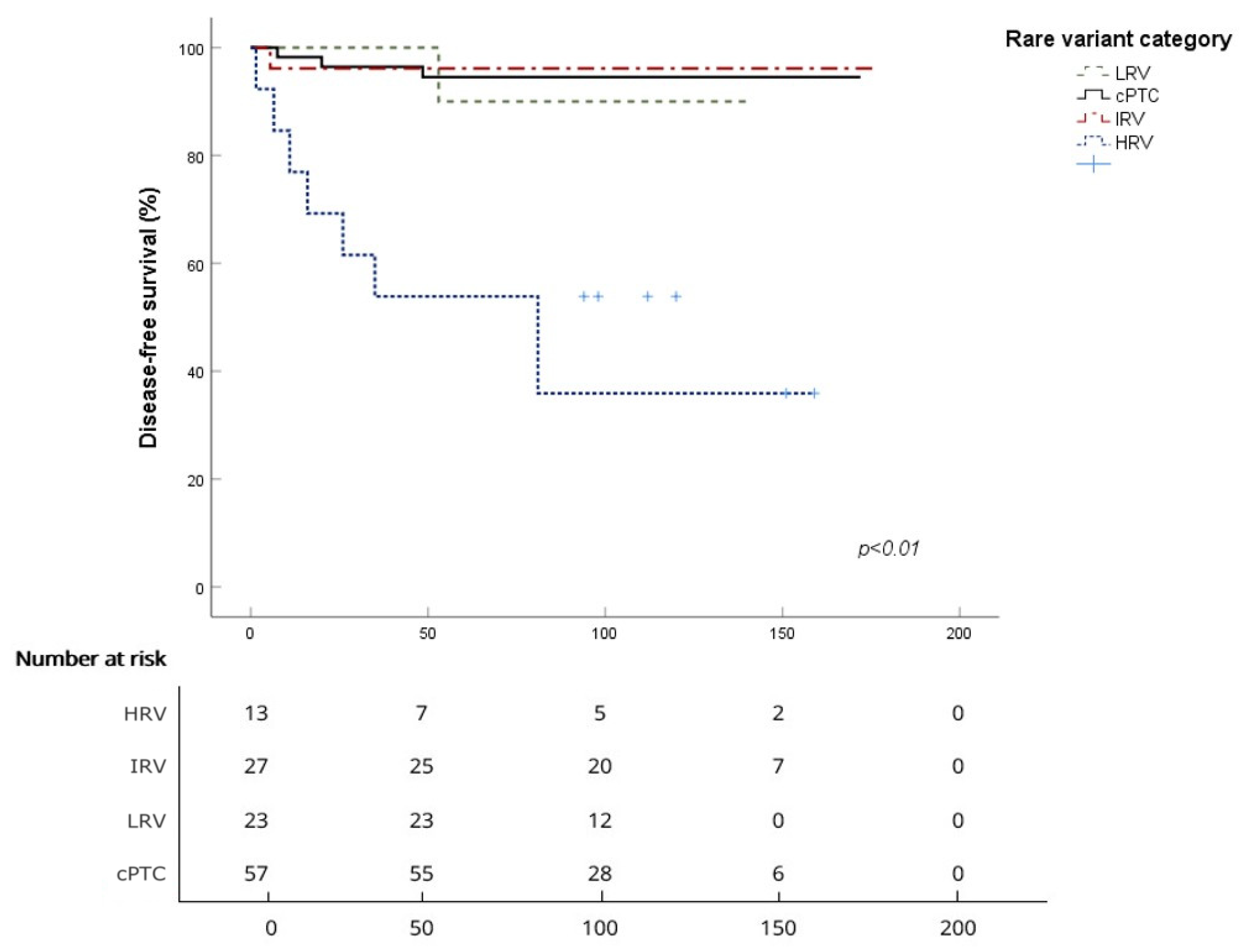

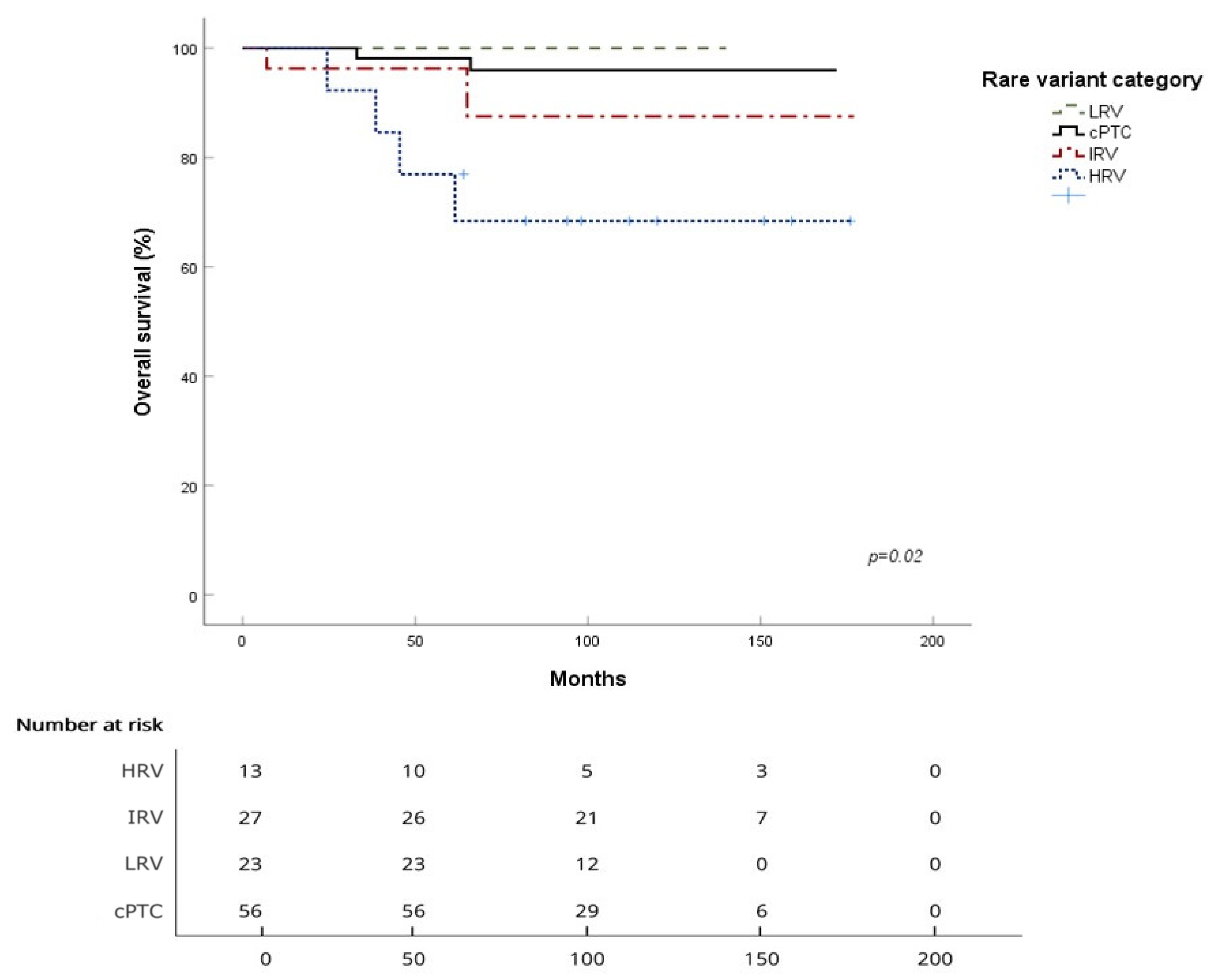

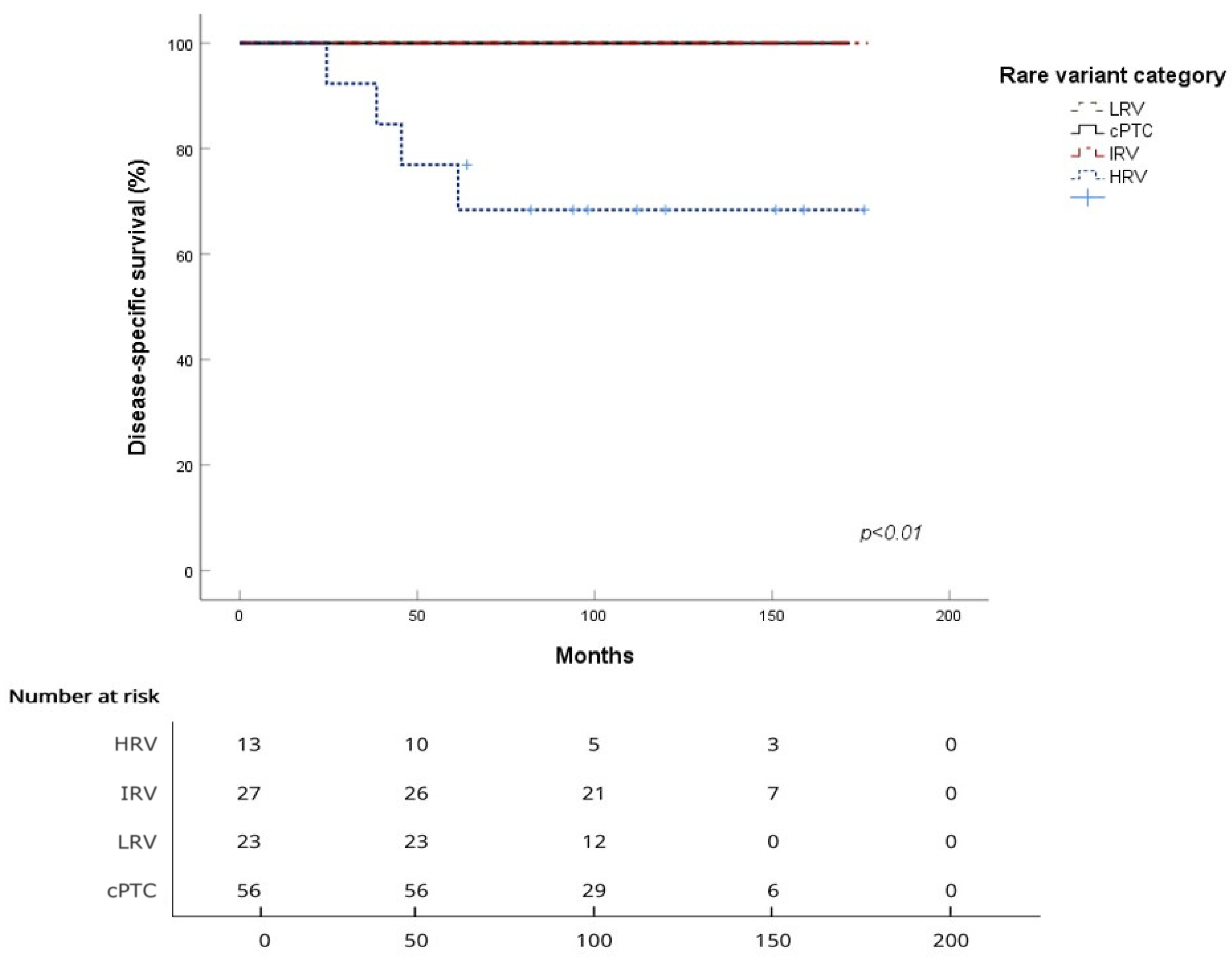

3.2. Survival Analysis for the Four Subgroups

| Survival | cPTC | HRV | IRV | LRV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean OS (months) | 167.8 ± 2.9 | 136.4 ± 16.5 | 165.6 ± 7.6 | / |

| 5-year OS | 98.1% | 76.9% | 96.3% | 100% |

| 10-year OS | 96.0% | 68.4% | 87.5% | 100% |

| Log-rank (vs. cPTC) | p = 0.001 | p = 0.58 | p = 0.36 | |

| Mean DSS (months) | / | 136.4 ± 16.5 | / | / |

| 5-year DSS | 100% | 76.9% | 100% | 100% |

| 10-year DSS | 100% | 68.4% | 100% | 100% |

| Log-rank (vs. cPTC) | p < 0.001 | / | / | |

| Mean DFS (months) | 164.6 ± 4.2 | 89.2 ± 18.7 | 170.5 ± 6.4 | 136.3 ± 3.5 |

| 5-year DFS | 96.4% | 53.8% | 96.2% | 100% |

| 10-year DFS | 94.5% | 40.4% | 96.2% | 90% |

| Log-rank (vs. cPTC) | p < 0.001 | p = 0.8 | p = 0.84 |

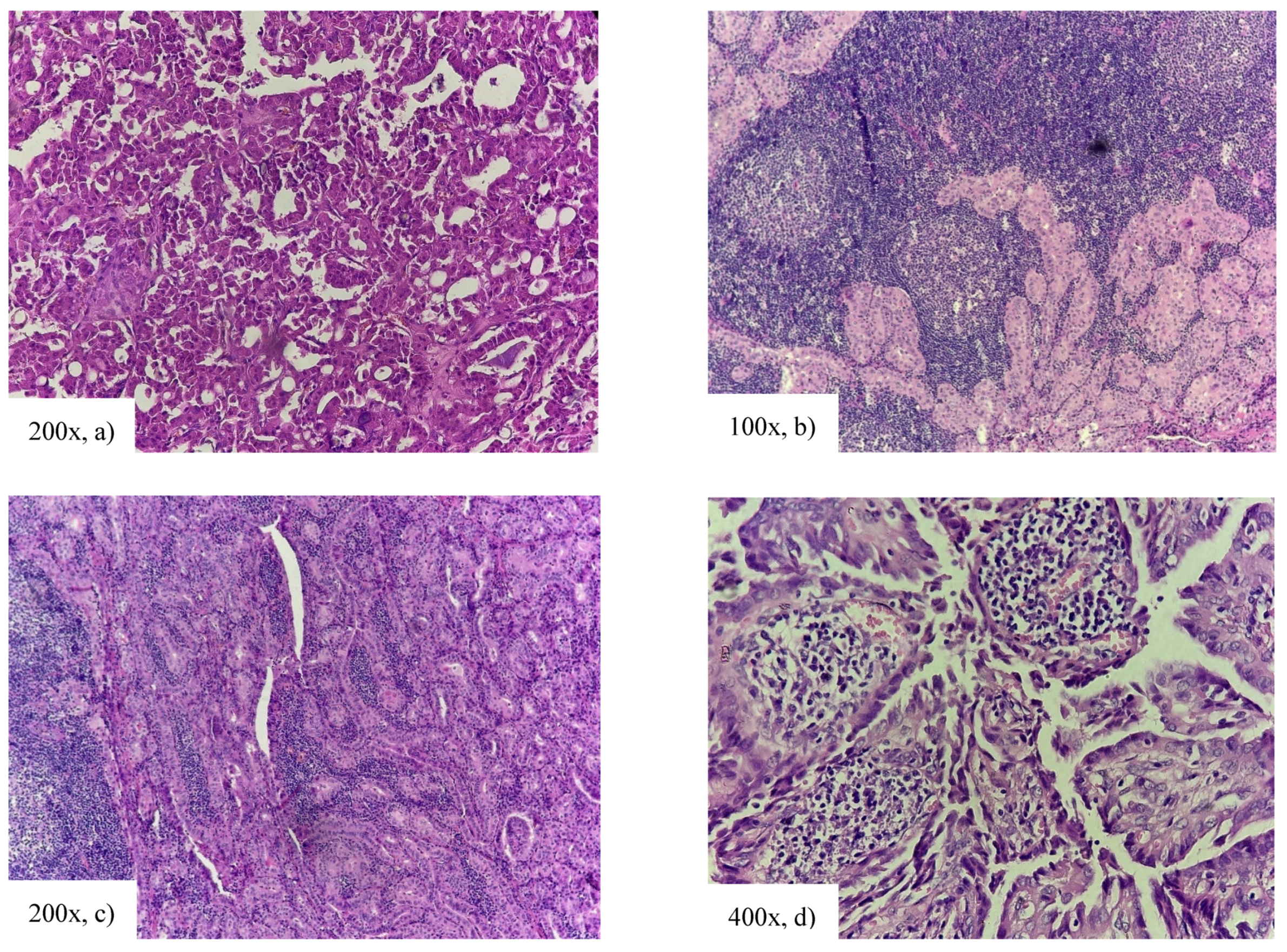

4. Discussion

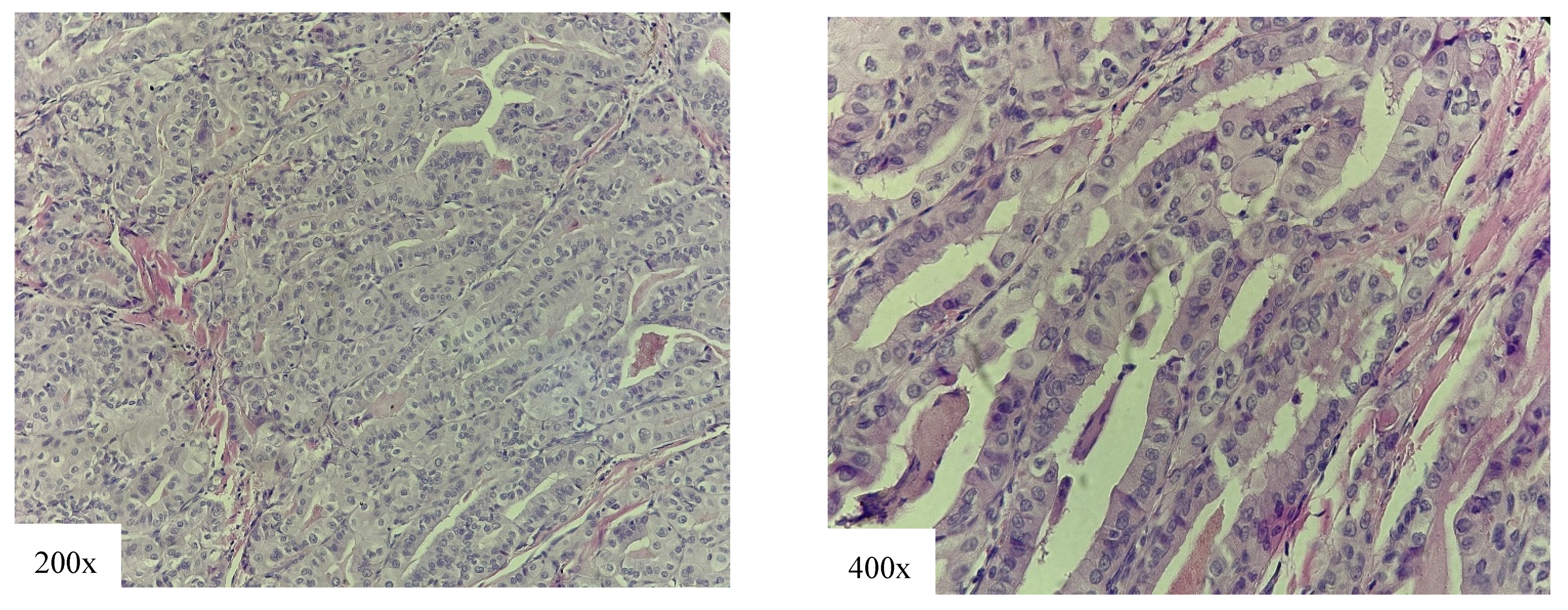

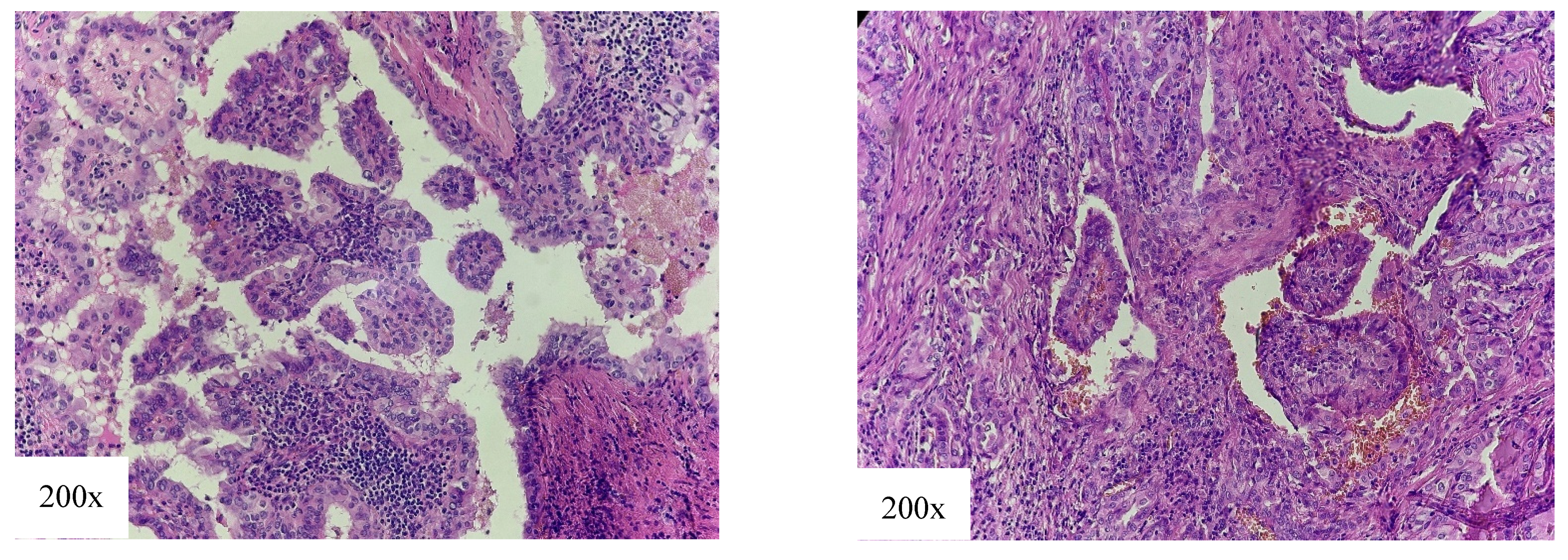

4.1. High-Risk Variants

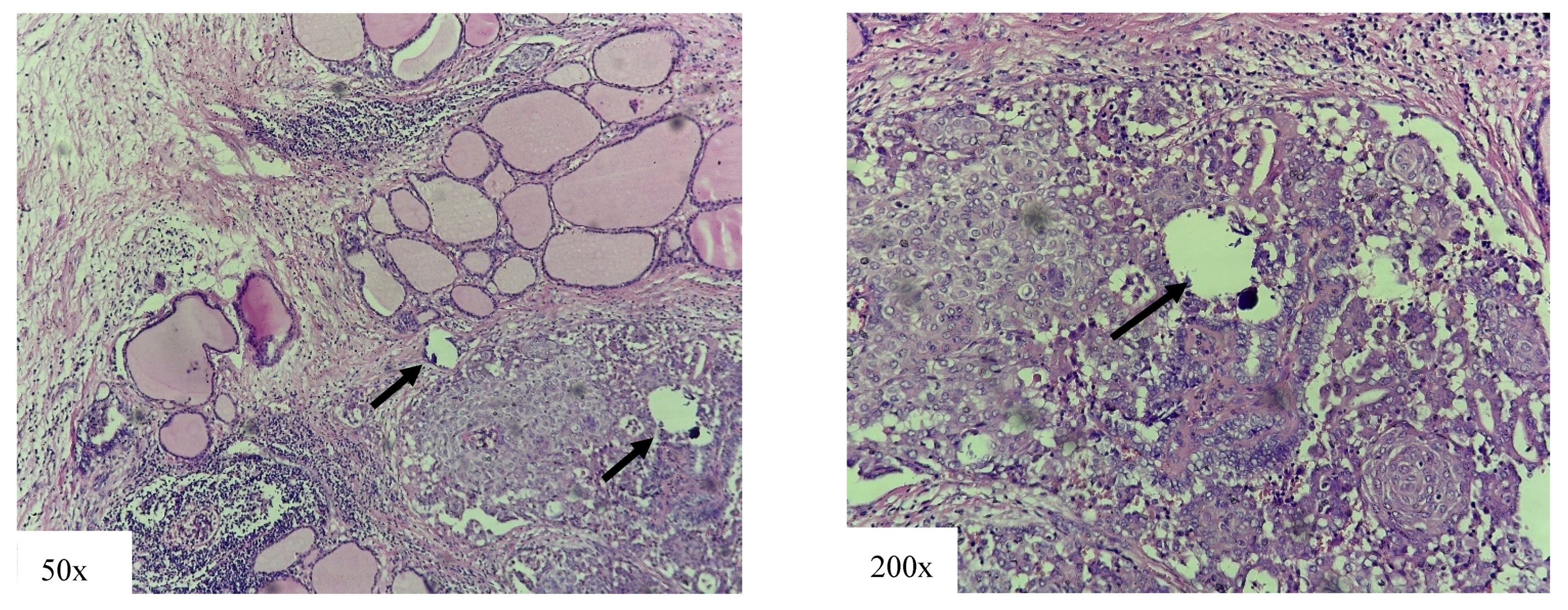

4.2. Intermediate-Risk Variant

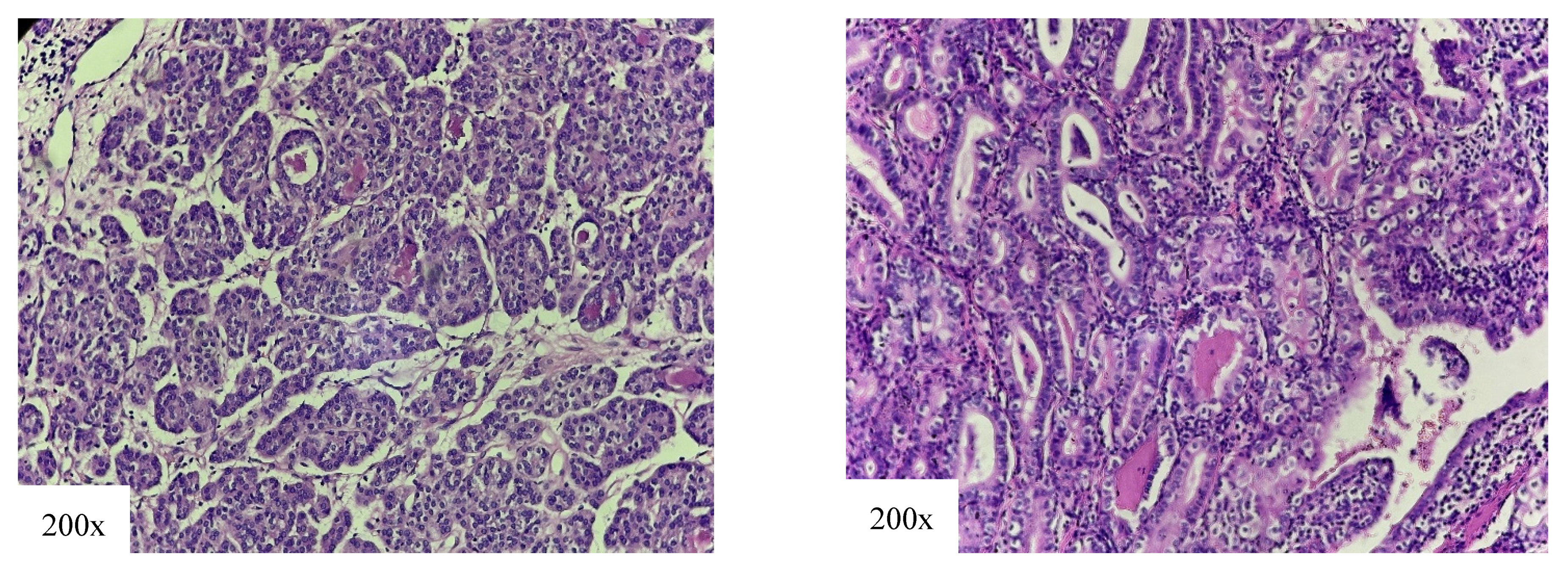

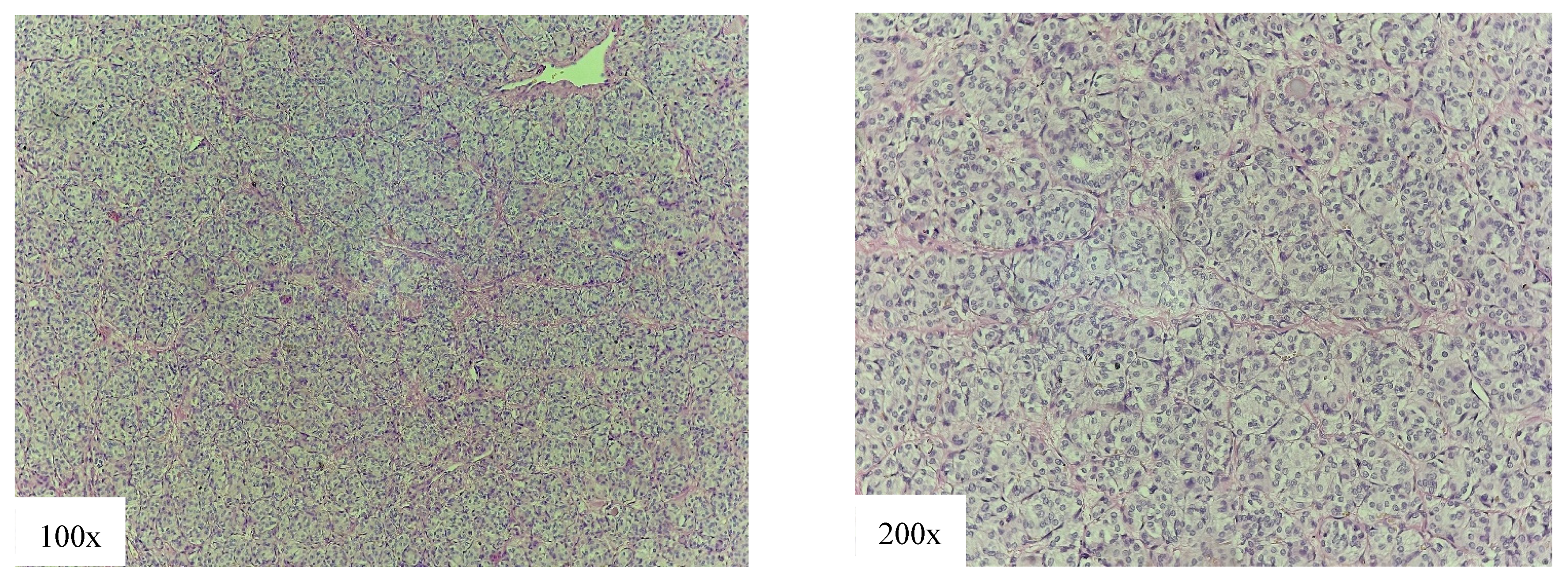

4.3. Low-Risk Variants

4.4. Risk Factors for Disease Recurrence

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boucai, L.; Zafereo, M.; Cabanillas, M.E. Thyroid Cancer A Review. JAMA 2024, 331, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Z.W.; LiVolsi, V.A. Special types of thyroid carcinoma. Histopathology 2018, 72, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Miyauchi, A.; Kihara, M.; Fukushima, M.; Higashiyama, T.; Miya, A. Overall Survival of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Patients: A Single-Institution Long-Term Follow-Up of 5897 Patients. World J. Surg. 2018, 42, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, H.G.; Odate, T.; Duong, U.N.P.; Mochizuki, K.; Nakazawa, T.; Katoh, R.; Kondo, T. Prognostic importance of solid variant papillary thyroid carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head. Neck 2018, 40, 1588–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Z.W.; Asa, S.L.; Barletta, J.A.; Ghossein, R.A.; Juhlin, C.C.; Jung, C.K.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Papotti, M.G.; Sobrinho-Simões, M.; Tallini, G.; et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms. Endocr. Pathol. 2022, 33, 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Viswanathan, K.; Zhang, L.; Edmund, L.N.; Ganly, O.; Tuttle, R.M.; Lubin, D.; Ghossein, R.A. The solid variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: A multi-institutional retrospective study. Histopathology 2022, 81, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berho, M.; Suster, S. The Oncocytic Variant of Papillary Carcinoma of the Thyroid: A Clinicopathologic Study of 15 Cases. Hum. Pathol. 1997, 28, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantri, S.H.; D’cruze, L.; Barathi, G.; Singh, B.K. Warthin-like papillary carcinoma thyroid. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2023, 19, 1471–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.A.; Yen, T.W.F.; Ortiz, D.I.; Hunt, B.C.; Fareau, G.; Massey, B.L.; Campbell, B.H.; Doffek, K.L.; Evans, D.B.; Wang, T.S. Patients with oncocytic variant papillary thyroid carcinoma have a similar prognosis to matched classical papillary thyroid carcinoma controls. Thyroid 2018, 28, 1462–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, R.; Muñoz, F.; Donoso, F.; López, J.; Bruera, M.J.; Ruiz-Esquide, M.; Mosso, L.; Lustig, N.; Solar, A.; Droppelmann, N.; et al. Warthin-like and classic papillary thyroid cancer have similar clinical presentation and prognosis. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 64, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyucu, K.; Ince, S.; Cinar, A.; San, H.; Samsum, M.; Dizdar, N.; Alagoz, E.; Demirci, I.; Ozkara, M.; Gunalp, B.; et al. Clinical behaviour of papillary thyroid cancer oncocytic variant: Stage-matched comparison versus classical and tall cell variant papillary thyroid cancer. Rev. Española Med. Nucl. Imagen Mol. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 42, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizbay Sak, S. Variants of papillary thyroid carcinoma: Multiple faces of a familiar tumor. Turk. J. Pathol. 2015, 31, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, M.C.; Erickson, L.A. Aggressive Variants of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: Hobnail, Tall Cell, Columnar, and Solid. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2018, 25, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Cho, S.W.; Park, Y.J.; Ahn, H.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Suh, Y.J.; Choi, D.; Kim, B.K.; Yang, G.E.; Park, I.-S.; et al. Clinicopathological Characteristics and Recurrence-Free Survival of Rare Variants of Papillary Thyroid Carcinomas in Korea: A Retrospective Study. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 36, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.S.; Luu, M.; Barrios, L.; Chen, I.; Melany, M.; Ali, N.; Patio, C.; Chen, Y.; Bose, S.; Fan, X.; et al. Incidence and Mortality Risk Spectrum Across Aggressive Variants of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushchayev, S.; Kushchayeva, Y.; Glushko, T.; Pestun, I.; Teytelboym, O. Discovery of metastases in thyroid cancer and “benign metastasizing goiter”: A historical note. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1354750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Prera, J.C.; Machado, R.A.; Asa, S.L.; Baloch, Z.; Faquin, W.C.; Ghossein, R.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Lloyd, R.V.; Mete, O.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; et al. Pathologic Reporting of Tall-Cell Variant of Papillary Thyroid Cancer: Have We Reached a Consensus? Thyroid 2017, 27, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Egan, C.E.; Greenberg, J.A.; Marshall, T.; Tumati, A.; Finnerty, B.M.; Beninato, T.; Zarnegar, R.; Fahey, T.J.; Arenas, M.A.R. Patterns in the Reporting of Aggressive Histologic Subtypes in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. J. Surg. Res. 2024, 298, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldkamp, J.; Führer, D.; Luster, M.; Musholt, T.J.; Spitzweg, C.; Schott, M. Fine Needle Aspiration in the Investigation of Thyroid Nodules. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2016, 113, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciputra, E.H.; Syamsu, S.A.; Smaradania, N.; Hamid, F.; Faruk, M. Accuracy of the Combination of TI-RADS and BETHESDA Regarding Histopathology of Thyroid Malignancy. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Biol. 2025, 10, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasa, I.N.W.T.; Maheswari, L.P.D.; Suryawisesa, I.B.M.; Irawan, H.; Sudarsa, I.W.; Bharata, M.D.Y.; Widarsa, I.K.T. The Accuracy of FNAB as Diagnostic Tool For Thyroid Cancer Compared to Anatomical Pathology Results as Gold Standard at Sanjiwani Hospital, Gianyar. J. Bedah Nas. 2024, 8, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.G.; da Silva, L.F.F.; de Araujo-Filho, V.J.F.; Mosca, L.d.M.; de Araujo-Neto, V.J.F.; Kowalski, L.P.; Carneiro, P.C. Incidental thyroid carcinoma: Correlation between FNAB cytology and pathological examination in 1093 cases. Clinics 2022, 77, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, A.S.; Jung, C.K. Cytologic hallmarks and differential diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma subtypes. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2024, 58, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, A.; Gupta, P.K.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Baloch, Z.W. Distinguishing tall cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma from usual variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma in cytologic specimens. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2002, 27, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleria, P.; Phulware, R.; Agarwal, S.; Jain, D.; Mathur, S.R.; Iyer, V.K.; Ballal, S.; Bal, C.S. Cytopathology of solid variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: Differential diagnoses with other thyroid tumors. Acta Cytol. 2018, 62, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca-Pelaz, A.; Shah, J.P.; Hernandez-Prera, J.C.; Ghossein, R.A.; Rodrigo, J.P.; Hartl, D.M.; Olsen, K.D.; Shaha, A.R.; Zafereo, M.; Suarez, C.; et al. Papillary Thyroid Cancer—Aggressive Variants and Impact on Management: A Narrative Review. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 3112–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, C.K. Papillary thyroid carcinoma variants with tall columnar cells. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2020, 54, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, W.; Liu, C.; Li, J. Tall cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: Current evidence on clinicopathologic features and molecular biology. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 40792–40799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, T.A.; Hrafnkelsson, J.; Olafsdottir, E.J.; Jonasson, J.G. Tall cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: A population-based study in Iceland. Thyroid 2015, 25, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.G.T.; Shaha, A.R.; Tuttle, R.M.; Sikora, A.G.; Ganly, I. Tall-cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: A matched-pair analysis of survival. Thyroid 2010, 20, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazaure, H.S.; Roman, S.A.; Sosa, J.A. Aggressive variants of papillary thyroid cancer: Incidence, characteristics and predictors of survival among 43,738 patients. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 1874–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.; Gopalan, V.; Smith, R.A.; Lam, A.K.Y. Diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma-an update of its clinicopathological features and molecular biology. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2015, 94, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, H.G.; Kondo, T.; Pham, T.Q.; Oishi, N.; Mochizuki, K.; Nakazawa, T.; Hassell, L.; Katoh, R. Prognostic significance of diffuse sclerosing variant papillary thyroid carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 176, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chereau, N.; Giudicelli, X.; Pattou, F.; Lifante, J.C.; Triponez, F.; Mirallié, E.; Goudet, P.; Brunaud, L.; Trésallet, C.; Tissier, F.; et al. Diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma is associated with aggressive histopathological features and a poor outcome: Results of a large multicentric study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 4603–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, M.; Xiao, L.; Li, L.; Dong, P. Diffuse Sclerosing Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma is Related to A Poor Outcome: A Comparison Study Using Propensity Score Matching. Endocr. Pr. 2023, 29, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.S.; Hong, S.; Park, C.S. Diffuse Sclerosing Variant Is a Major Subtype of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma in the Young. Thyroid 2009, 19, 1225–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Koo, J.S.; Bang, J.I.; Kim, J.K.; Kang, S.W.; Jeong, J.J.; Nam, K.-H.; Chung, W.Y. Relationship between recurrence and age in the diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: Clinical significance in pediatric patients. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1359875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janovitz, T.; Williamson, D.F.K.; Wong, K.S.; Dong, F.; Barletta, J.A. Genomic profile of columnar cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Histopathology 2021, 79, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sywak, M.; Pasieka, J.L.; Ogilvie, T. A Review of Thyroid Cancer with Intermediate Differentiation. J. Surg. Oncol. 2004, 86, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Shin, J.H.; Hahn, S.Y.; Oh, Y.L. Columnar cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: Ultrasonographic and clinical differentiation between the indolent and aggressive types. Korean J. Radiol. 2018, 19, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Faquin, W.C.; Lloyd, R.V.; Nosé, V. Clinicopathological and molecular characterization of nine cases of columnar cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2011, 24, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, M.; Mermod, M.; Canberk, S.; Saglietti, C.; Sykiotis, G.P.; Pusztaszeri, M.; Ragazzi, M.; Mazzucchelli, L.; Giovanella, L.; Piana, S. Columnar cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: Cytomorphological characteristics of 11 cases with histological correlation and literature review. Cancer Cytopathol. 2017, 125, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, L.B.; Yan, F.; Morgan, P.F.; Kaczmar, J.M.; Fernandes, J.K.; Nguyen, S.A.; Jester, R.L.; Day, T.A. Hobnail variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 2021, 72, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asioli, S.; Erickson, L.A.; Sebo, T.J.; Zhang, J.; Jin, L.; Thompson, G.B.; Lloyd, R.V. Papillary thyroid carcinoma with prominent hobnail features: A new aggressive variant of moderately differentiated papillary carcinoma. A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular study of eight cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 34, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longheu, A.; Canu, G.L.; Calò, P.G.; Cappellacci, F.; Erdas, E.; Medas, F. Tall cell variant versus conventional papillary thyroid carcinoma: A retrospective analysis in 351 consecutive patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zeng, W.; Chen, T.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, C.; Huang, T. A comparison of the clinicopathological features and prognoses of the classical and the tall cell variant of papillary thyroid cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 6222–6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandrino, P.; Russo, M.; Regalbuto, C.; Pellegriti, G.; Moleti, M.; Caff, A.; Squatrito, S.; Vigneri, R. Outcome of the Diffuse Sclerosing Variant of Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watutantrige-Fernando, S.; Vianello, F.; Barollo, S.; Bertazza, L.; Galuppini, F.; Cavedon, E.; Censi, S.; Benna, C.; Ide, E.C.; Parisi, A.; et al. The Hobnail Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: Clinical/Molecular Characteristics of a Large Monocentric Series and Comparison with Conventional Histotypes. Thyroid 2018, 28, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.; Min Jeon, J.; Oh, H.-S.; Han, M.; Lee, Y.-M.; Kim, T.Y.; Chung, K.-W.; Kim, W.B.; Shong, Y.K.; Song, D.E.; et al. Do aggressive variants of papillary thyroid carcinoma have worse clinical outcome than classic papillary thyroid carcinoma? Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 179, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poma, A.M.; Macerola, E.; Proietti, A.; Vignali, P.; Sparavelli, R.; Torregrossa, L.; Matrone, A.; Basolo, A.; Elisei, R.; Santini, F.; et al. Clinical–Pathological Features and Treatment Outcome of Patients With Hobnail Variant Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 842424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.; Lu, D.; Shao, C.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J. Clinical prognostic risk assessment of different pathological subtypes of papillary thyroid cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2025, 410, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Taibo, R.; Peteiro-González, D.; Cabezas-Agrícola, J.M.; Aliyev, E.; Barreiro-Morandeira, F.; Ruiz-Ponte, C.; Cameselle-Teijeiro, J.M. Aggressiveness of the tall cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma is independent of the tumor size and patient age. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 3501–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiforov, Y.E.; Erickson, L.A.; Nikiforova, M.N.; Caudill, C.M.; Lloyd, R.V. Solid variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: Incidence, clinical-pathologic characteristics, molecular analysis, and biologic behavior. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2001, 25, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizukami, Y.; Noguchi, M.; Michigishi, T.; Nonomura, A.; Hashimoto, T.; Otake, S.; Nakamura, S.; Matsubara, F. Papillary thyroid carcinoma in Kanazawa, Japan: Prognostic significance of histological subtypes. Histopathology 1992, 20, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.; Kim, S.M.; Chun, K.W.; Kim, B.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Chang, H.S.; Hong, S.W.; Park, C.S. Clinicopathologic features of solid variant papillary thyroid cancer. ANZ J. Surg. 2014, 84, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.A.; Bakarev, M.A.; Lushnikova, E.L. Histological Variants of Papillary Thyroid Cancer in Relation to Clinical and Morphological Parameters and Prognosis. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 174, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofer Juhlin, C.; Mete, O.; Baloch, Z.W. The 2022 WHO classification of thyroid tumors: Novel concepts in nomenclature and grading. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2023, 30, e220293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poma, A.M.; Macerola, E.; Ghossein, R.A.; Tallini, G.; Basolo, F. Prevalence of Differentiated High-Grade Thyroid Carcinoma Among Well-Differentiated Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thyroid 2024, 34, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volante, M.; Collini, P.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Sakamoto, A.; Kakudo, K.; Katoh, R.; Lloyd, R.V.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Papotti, M.; Sobrinho-Simoes, M.; et al. Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma: The Turin proposal for the use of uniform diagnostic criteria and an algorithmic diagnostic approach. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2007, 31, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Dong, W.; Zhang, D.; Lv, C.; Shao, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, H. Clinicopathological Characteristics and Prognosis of Poorly Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma Diagnosed According to the Turin Criteria. Endocr. Pract. 2021, 27, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, M.; Eliashar, R.; Ben-Yaakov, A.; Weinberger, J.M.; Maly, B. Clinicopathologic Features and Outcome of the Oncocytic Variant of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma From the Departments of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Gross. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2009, 118, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Hasteh, F. Oncocytic variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma associated with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: A case report and review of the literature. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2009, 37, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, M.K.; Bae, J.S.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.H.; Lim, D.J.; Lee, Y.S.; Jung, C.K. The warthin-like variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: A comparison with classic type in the patients with coexisting hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 456027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Thomas, S. An aggressive case of Warthin-like variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC). Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 156, S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Singh, A.; Jat, B.; Phulware, R.H. Cytomorphology of Warthin-like variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: A diagnosis not to be missed. Cytopathology 2021, 32, 840–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clinicopathological Features | cPTC | HRV | HRV vs. cPTC | IRV | IRV vs. cPTC | LRV | LRV vs. cPTC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsular invasion | 26.3% | 60% | p = 0.015 | 15% | p = 0.1 | 64% | p = 0.043 |

| Vascular invasion | 5% | 53.3% | p < 0.001 | 2.5% | p = 0.67 | 32% | p < 0.001 |

| LN metastases | 5% | 40% | p < 0.001 | 2.5% | p = 0.67 | 28% | p = 0.003 |

| Distant metastases | 0% | 0% | p = 1.0 | 0% | p = 1.0 | 0% | p = 1.0 |

| Microscopic ETE | 12.5% | 53.3% | p < 0.001 | 7.5% | p = 0.54 | 20% | p = 0.34 |

| Gross ETE | 5% | 40% | p < 0.001 | 2.5% | p = 0.67 | 8% | p = 0.63 |

| Multifocal presentation | 48.8% | 66.7% | p < 0.001 | 20% | p = 0.45 | 52% | p < 0.001 |

| Bilateral presentation | 37.5% | 66.7% | p < 0.001 | 10% | p < 0.001 * | 50% | p < 0.001 |

| Recurrence | 5.3% | 53.8% | p < 0.001 | 3.6% | p = 1.0 | 4.3% | p = 1.0 |

| RAI treatment | 37.5% | 84.6% | p < 0.001 | 24% | p = 0.87 | 60.9% | p = 0.043 |

| Cancer-specific death | 0% | 30% | p < 0.001 | 0% | p = 1.0 | 0% | p = 1.0 |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Capsular invasion | 2.22 | 0.68–7.25 | 0.19 | |||

| Vascular invasion | 5.89 | 1.67–20.76 | 0.006 | 0.19 | 0.009–4.29 | 0.29 |

| Multifocal presentation | 4.28 | 1.11–16.45 | 0.034 | 0.55 | 0.003–107.5 | 0.83 |

| Bilateral presentation | 6.38 | 1.65–24.67 | 0.007 | 5.63 | 0.03–1076 | 0.52 |

| LN metastases | 11.25 | 3.14–40.32 | <0.001 | 4.1 | 0.43–39 | 0.22 |

| Microscopic ETE | 9.43 | 2.72–32.75 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 0.057–29.2 | 0.87 |

| Gross ETE | 20.0 | 5.12–78.13 | <0.001 | 6.36 | 0.31–128.7 | 0.228 |

| HRV | 22.46 | 4.83–104.34 | <0.001 | 15.82 | 1.76–142.3 | 0.014 |

| IRV | 0.66 | 0.07–6.54 | 0.72 | |||

| LRV | 1.07 | 0.1–10.76 | 0.95 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ilic, J.; Slijepcevic, N.; Tausanovic, K.; Odalovic, B.; Zoric, G.; Milinkovic, M.; Rovcanin, B.; Jovanovic, M.; Buzejic, M.; Vucen, D.; et al. Clinical Behavior of Aggressive Variants of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. Cancers 2026, 18, 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020345

Ilic J, Slijepcevic N, Tausanovic K, Odalovic B, Zoric G, Milinkovic M, Rovcanin B, Jovanovic M, Buzejic M, Vucen D, et al. Clinical Behavior of Aggressive Variants of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):345. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020345

Chicago/Turabian StyleIlic, Jovan, Nikola Slijepcevic, Katarina Tausanovic, Bozidar Odalovic, Goran Zoric, Marija Milinkovic, Branislav Rovcanin, Milan Jovanovic, Matija Buzejic, Duska Vucen, and et al. 2026. "Clinical Behavior of Aggressive Variants of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Retrospective Case–Control Study" Cancers 18, no. 2: 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020345

APA StyleIlic, J., Slijepcevic, N., Tausanovic, K., Odalovic, B., Zoric, G., Milinkovic, M., Rovcanin, B., Jovanovic, M., Buzejic, M., Vucen, D., Stepanovic, B., Ivanis, S., Parezanovic, M., Marinkovic, M., & Zivaljevic, V. (2026). Clinical Behavior of Aggressive Variants of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. Cancers, 18(2), 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020345