Prognostic Factors in the Treatment of Advanced Endometrial Cancer Patients: 12-Year Experience of an ESGO Certified Center

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Characteristics

2.2. Patients

- Histological confirmation of advanced endometrial cancer.

- Surgical treatment at our Gynecological–Oncology Unit.

- Synchronous neoplasia at the time of diagnosis.

- FIGO stage IIIC1i and IIIC2i.

- Recurrent endometrial cancer.

- Missing important survival data.

2.3. Data Collection

- Patient hospital identification number;

- Patient age;

- Body Mass Index (BMI);

- Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI);

- FIGO stage based on 2023 classification;

- Histological types;

- Tumor grade;

- Myometrial invasion;

- LVSI;

- Neo-therapies and adjuvant therapies;

- Residual disease after cytoreduction

- Time-related data:

- ○

- Date of surgery;

- ○

- Date of recurrence;

- ○

- Date of the last follow-up or death.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

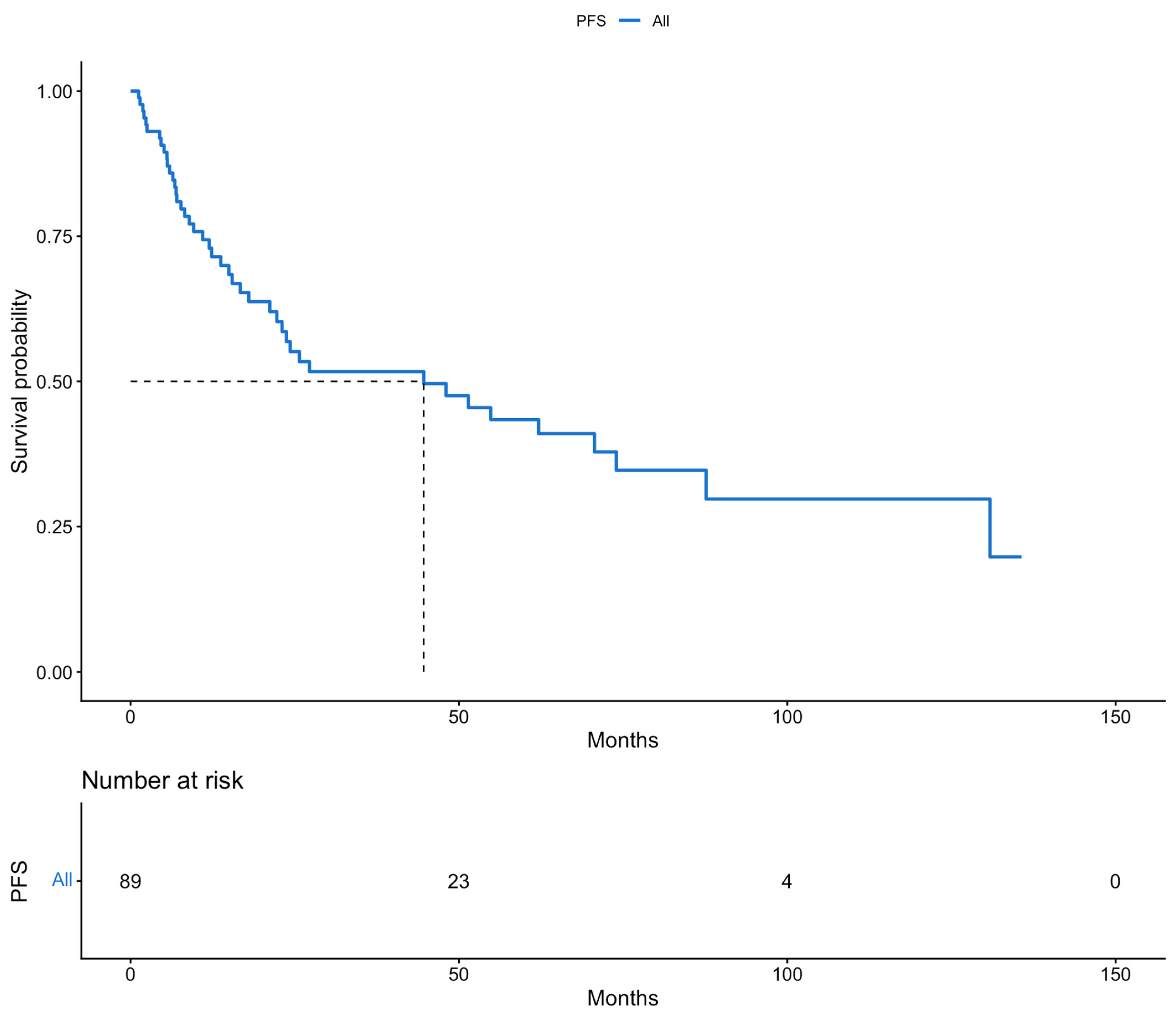

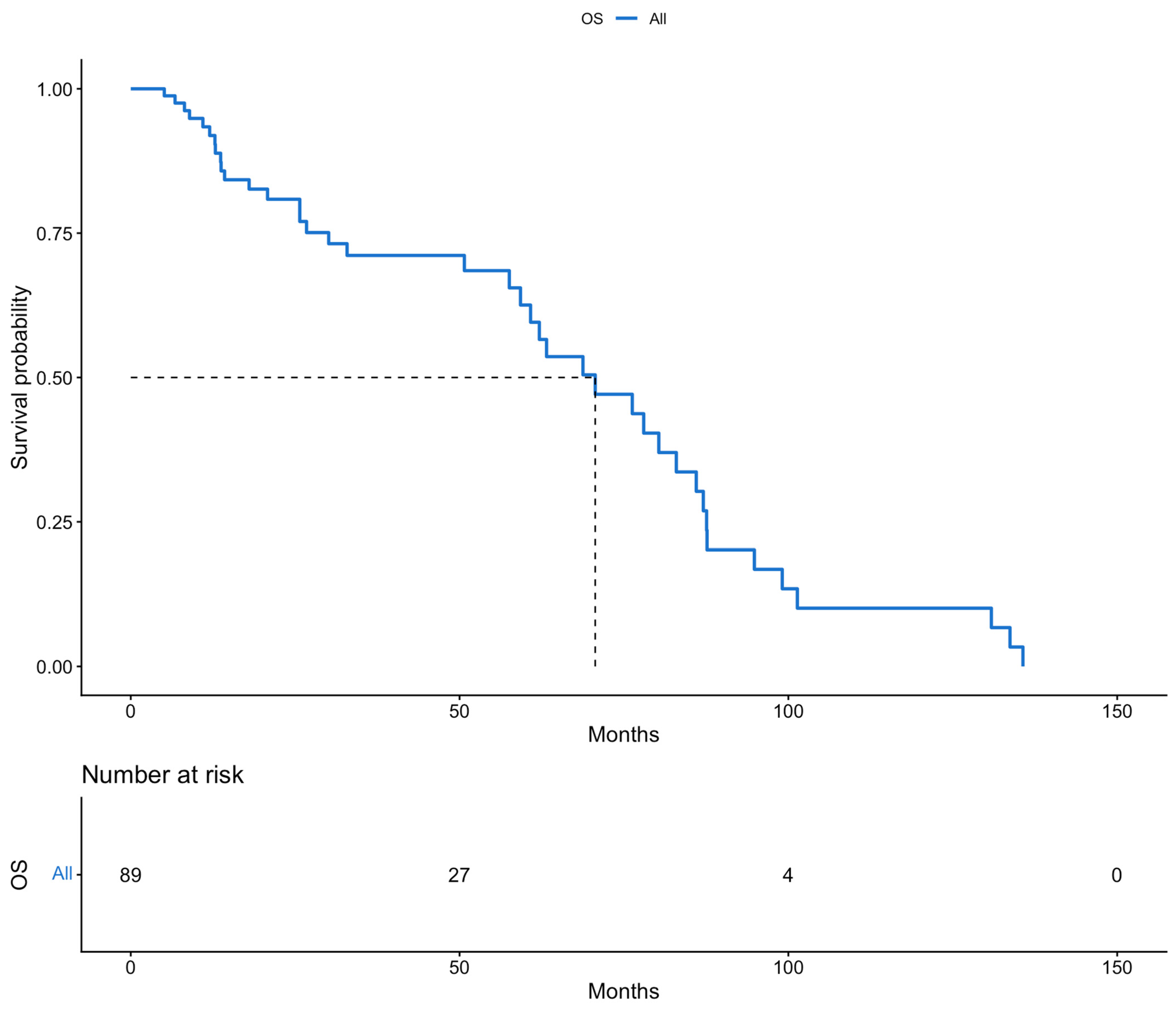

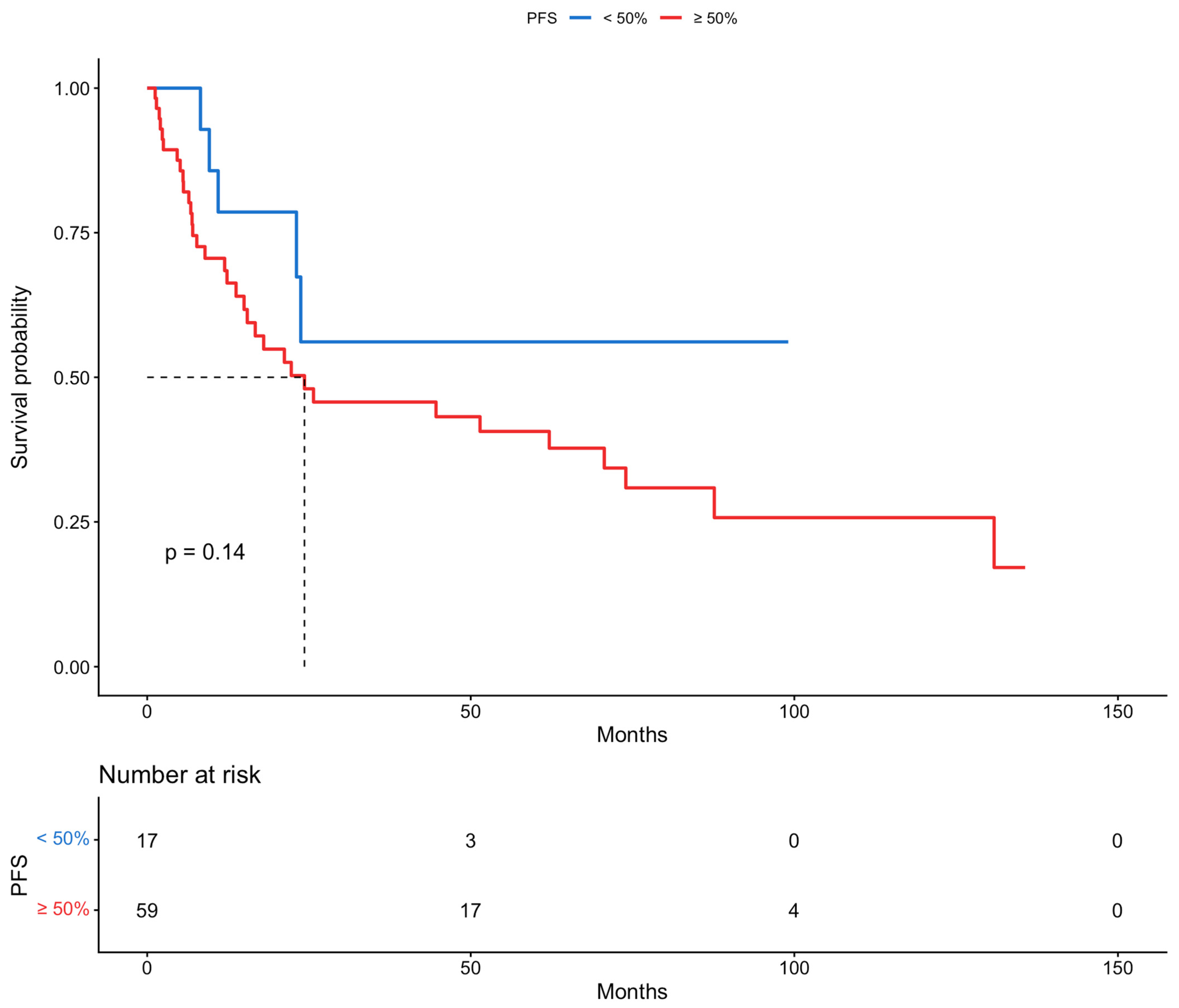

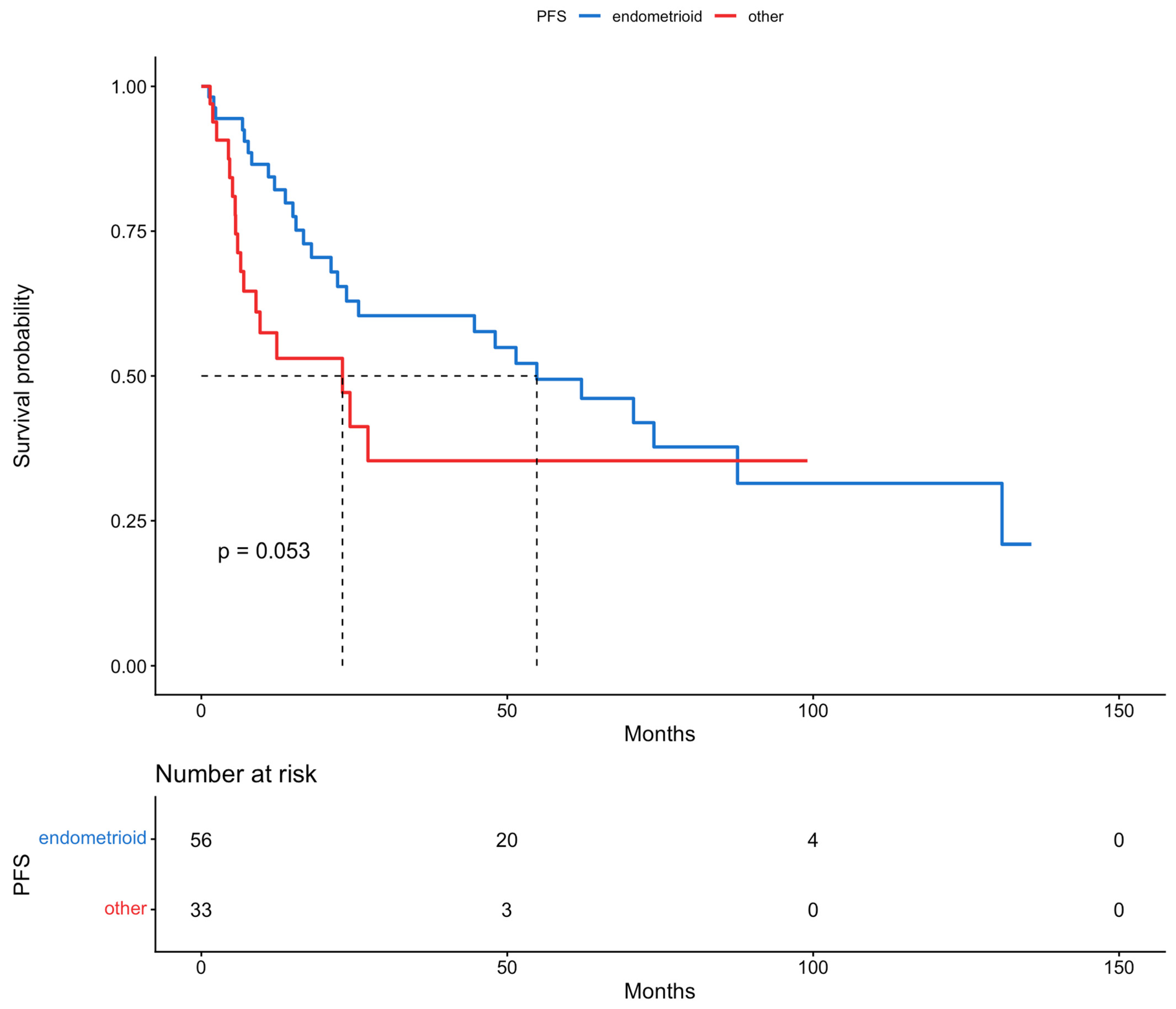

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, E.J.; Kitson, S.J.; McAlpine, J.N.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Powell, M.E.; Singh, N. Endometrial cancer. Lancet 2022, 399, 1412–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Gong, T.-T.; Liu, F.-H.; Jiang, Y.-T.; Sun, H.; Ma, X.-X.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Wu, Q.-J. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Endometrial Cancer, 1990-2017: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study, 2017. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, J. Global Trends in Incidence and Mortality Rates of Endometrial Cancer Among Individuals Aged 55 years and Above From 1990 to 2021: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease. Int. J. Womens Health 2025, 17, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Song, Z. Changing trends in the disease burden of uterine cancer globally from 1990 to 2019 and its predicted level in 25 years. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1361419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasegar, S.; Bashi, A.; Lang, S.M.; Liao, C.-I.; Johnson, C.; Darcy, K.M.; Tian, C.; Kapp, D.S.; Chan, J.K. Trends in Uterine Cancer Mortality in the United States: A 50-Year Population-Based Analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 142, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.D.; Prest, M.T.; Ferris, J.S.; Chen, L.; Xu, X.; Rouse, K.J.; Melamed, A.; Hur, C.; Heckman-Stoddard, B.M.; Samimi, G.; et al. Projected Trends in the Incidence and Mortality of Uterine Cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2025, 34, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijayabahu, A.T.; Shiels, M.S.; Arend, R.C.; Clarke, M.A. Uterine cancer incidence trends and 5-year relative survival by race/ethnicity and histology among women under 50 years. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 231, 526.e1–526.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.-Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Ruan, J.-Y.; Mu, Y.; Li, J.-K. Recurrence and survival of patients with stage III endometrial cancer after radical surgery followed by adjuvant chemo- or chemoradiotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, E.N.B.; Horeweg, N.; van der Marel, J.; Nooij, L.S. Survival benefit of cytoreductive surgery in patients with primary stage IV endometrial cancer: A systematic review & meta-analysis. BJC Rep. 2024, 2, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concin, N.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Cibula, D.; Colombo, N.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Ledermann, J.; Mirza, M.R.; Vergote, I.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Bosse, T.; et al. ESGO-ESTRO-ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma: Update 2025. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, e423–e435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouzoulas, D.; Tsolakidis, D.; Sofianou, I.; Tzitzis, P.; Pervana, S.; Topalidou, M.; Timotheadou, E.; Grimbizis, G. Molecular classification of endometrial cancer: Impact on adjuvant treatment planning. Cytojournal 2024, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berek, J.S.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Creutzberg, C.; Fotopoulou, C.; Gaffney, D.; Kehoe, S.; Lindemann, K.; Mutch, D.; Concin, N. FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 162, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pados, G.; Zouzoulas, D.; Tsolakidis, D. Recent management of endometrial cancer: A narrative review of the literature. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1244634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concin, N.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Vergote, I.; Cibula, D.; Mirza, M.R.; Marnitz, S.; Ledermann, J.; Bosse, T.; Chargari, C.; Fagotti, A.; et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogani, G.; Ditto, A.; Leone Roberti Maggiore, U.; Scaffa, C.; Mosca, L.; Chiappa, V.; Martinelli, F.; Lorusso, D.; Raspagliesi, F. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery for unresectable stage IVB Serous endometrial cancer. Tumori J. 2019, 105, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, C.J.; Chen, L.; Melamed, A.; St Clair, C.; Khoury-Collado, F.; Tergas, A.I.; Hou, J.Y.; Hur, C.; Ananth, C.V.; Neugut, A.I.; et al. Association of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy With Overall Survival in Women With Metastatic Endometrial Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2028612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, D.; Rema, P.; Suchetha, S.; Sivaranjith, J.; James, F.V.; Krishna, K.M.J. Advanced endometrial cancers—Outcome of patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery: A retrospective study. Indian J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 22, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiazzo, F.; Raspagliesi, F.; Chiappa, V.; Bruni, S.; Ceppi, L.; Bogani, G. Upfront and interval debulking surgery in advanced/metastatic endometrial cancer in the era of molecular classification. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2025, 310, 113958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, G.; Coada, C.A.; Di Costanzo, S.; Mezzapesa, F.; Genovesi, L.; Bogani, G.; Raspagliesi, F.; Morganti, A.G.; De Iaco, P.; Perrone, A.M. Primary or Interval Debulking Surgery for Advanced Endometrial Cancer with Carcinosis: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of Survival Outcomes. Cancers 2025, 17, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, B.B.; Monuszko, K.A.; Kaplan, S.J.; Davidson, B.A.; Moss, H.A.; Huang, A.B.; Melamed, A.; Wright, J.D.; Havrilesky, L.J.; Previs, R.A. Primary cytoreductive surgery for advanced stage endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 237.e1–237.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakkerman, F.C.; Wu, J.; Putter, H.; Jürgenliemk-Schulz, I.M.; Jobsen, J.J.; Lutgens, L.C.H.W.; Haverkort, M.A.D.; de Jong, M.A.; Mens, J.W.M.; Wortman, B.G.; et al. Prognostic impact and causality of age on oncological outcomes in women with endometrial cancer: A multimethod analysis of the randomised PORTEC-1, PORTEC-2, and PORTEC-3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creutzberg, C.L.; Nout, R.A.; Lybeert, M.L.M.; Wárlám-Rodenhuis, C.C.; Jobsen, J.J.; Mens, J.-W.M.; Lutgens, L.C.H.W.; Pras, E.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; van Putten, W.L.J. Fifteen-Year Radiotherapy Outcomes of the Randomized PORTEC-1 Trial for Endometrial Carcinoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2011, 81, e631–e638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortman, B.G.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Putter, H.; Jürgenliemk-Schulz, I.M.; Jobsen, J.J.; Lutgens, L.C.H.W.; van der Steen-Banasik, E.M.; Mens, J.W.M.; Slot, A.; Kroese, M.C.S.; et al. Ten-year results of the PORTEC-2 trial for high-intermediate risk endometrial carcinoma: Improving patient selection for adjuvant therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C.C.B.; de Boer, S.M.; Powell, M.E.; Mileshkin, L.; Katsaros, D.; Bessette, P.; Leary, A.; Ottevanger, P.B.; McCormack, M.; Khaw, P.; et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in women with high-risk endometrial cancer (PORTEC-3): 10-year clinical outcomes and post-hoc analysis by molecular classification from a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, 1370–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhawech-Fauceglia, P.; Herrmann, R.F.; Kesterson, J.; Izevbaye, I.; Lele, S.; Odunsi, K. Prognostic factors in stages II/III/IV and stages III/IV endometrioid and serous adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 36, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, A.B.; Wu, J.; Chen, L.; Albright, B.B.; Previs, R.A.; Moss, H.A.; Davidson, B.A.; Havrilesky, L.J.; Melamed, A.; Wright, J.D. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced stage endometrial cancer: A systematic review. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 38, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubauer, N.L.; Lurain, J.R. The role of lymphadenectomy in surgical staging of endometrial cancer. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 2011, 814649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euscher, E.; Fox, P.; Bassett, R.; Al-Ghawi, H.; Ali-Fehmi, R.; Barbuto, D.; Djordjevic, B.; Frauenhoffer, E.; Kim, I.; Hong, S.R.; et al. The pattern of myometrial invasion as a predictor of lymph node metastasis or extrauterine disease in low-grade endometrial carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 37, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malpica, A.; Euscher, E.D.; Hecht, J.L.; Ali-Fehmi, R.; Quick, C.M.; Singh, N.; Horn, L.-C.; Alvarado-Cabrero, I.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Hirschowitz, L.; et al. Endometrial Carcinoma, Grossing and Processing Issues: Recommendations of the International Society of Gynecologic Pathologists. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2019, 38, S9–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Patients (N) | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | median: 64 | IQR: 57–78 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | median: 29.9 | IQR: 24.9–36.6 | |

| CCI | median: 3 | IQR: 2–4 | |

| 0–2 | 31 | 34.9 | |

| 3–4 | 43 | 48.2 | |

| ≥5 | 15 | 16.9 | |

| Myometrial invasion | |||

| <50% | 17 | 19.1 | |

| ≥50% | 59 | 66.3 | |

| unknown | 13 | 14.6 | |

| LVSI | |||

| no | 47 | 52.8 | |

| focal | 6 | 6.8 | |

| substantial | 36 | 40.4 | |

| Histological subtype | |||

| endometrioid | 56 | 62.9 | |

| other | 33 | 37.1 | |

| Tumor grade | |||

| low | 31 | 34.8 | |

| high | 58 | 65.2 | |

| FIGO stage | |||

| III | 67 | 75.3 | |

| IV | 22 | 24.7 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | |||

| chemoradiation | 40 | 45 | |

| adjuvant chemotherapy | 10 | 11.2 | |

| NACT | 13 | 14.6 | |

| radiotherapy | 26 | 29.2 | |

| Residual disease (cm) | |||

| 0 | 82 | 92.1 | |

| <1 | 2 | 2.3 | |

| ≥1 | 5 | 5.6 | |

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-Value | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Age (years) | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 | <0.05 | 1.03 | 0.99–1.05 | 0.0658 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.97 | 0.91–1.03 | 0.335 | ||||

| CCI | 1.06 | 0.93–1.21 | 0.377 | ||||

| Myometrial invasion | |||||||

| <50% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| ≥50% | 2.00 | 0.78–5.15 | 0.148 | 3.25 | 1.19–8.89 | 0.0219 | |

| LVSI | |||||||

| no | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| focal | 0.30 | 0.04–2.22 | 0.237 | ||||

| substantial | 1.21 | 0.65–2.24 | 0.538 | ||||

| Histological subtype | |||||||

| endometrioid | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| other | 1.84 | 0.98–3.42 | 0.0562 | 2.54 | 1.18–5.44 | 0.017 | |

| Tumor grade | |||||||

| low | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| high | 1.58 | 0.81–3.06 | 0.18 | ||||

| FIGO stage | |||||||

| III | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| IV | 2.85 | 1.54–5.30 | <0.05 | 1.93 | 0.97–3.86 | 0.0625 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | |||||||

| chemoradiation | 1.30 | 0.65–2.63 | 0.461 | ||||

| adjuvant chemotherapy | 1.83 | 0.76–4.40 | 0.178 | ||||

| NACT | 1.55 | 0.56–4.28 | 0.398 | ||||

| radiotherapy | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Residual disease (cm) | |||||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| <1 | 1.19 | 0.21–2.19 | 0.815 | ||||

| ≥1 | 0.67 | 0.27–5.23 | 0.507 | ||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-Value | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Age (years) | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 | 0.175 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 | 0.442 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.97 | 0.92–1.06 | 0.693 | ||||

| CCI | 1.03 | 0.89–1.18 | 0.732 | ||||

| Myometrial invasion | |||||||

| <50% | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥50% | 1.10 | 0.48–2.52 | 0.819 | ||||

| LVSI | |||||||

| no | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| focal | 3.26 × 10−8 | 0.00–Inf | 0.997 | ||||

| substantial | 0.74 | 0.36–151 | 0.405 | ||||

| Histological subtype | |||||||

| endometrioid | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| other | 1.27 | 0.58–2.76 | 0.548 | ||||

| Tumor grade | |||||||

| low | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| high | 1.44 | 0.73–2.85 | 0.297 | ||||

| FIGO stage | |||||||

| III | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| IV | 0.85 | 0.37–1.93 | 0.693 | ||||

| Adjuvant therapy | |||||||

| chemoradiation | 2.18 | 0.17–10.50 | 0.0363 | 1.90 | 0.86–4.22 | 0.115 | |

| adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.97 | 0.33–2.88 | 0.9526 | 0.84 | 0.27–2.65 | 0.766 | |

| NACT | 0.75 | 0.10–5.87 | 0.7824 | 0.70 | 0.09–5.54 | 0.738 | |

| radiotherapy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Residual disease (cm) | |||||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| <1 | 0.74 | 0.17–3.27 | 0.693 | ||||

| ≥1 | 0.85 | 0.32–2.26 | 0.75 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zouzoulas, D.; Sofianou, I.; Markopoulou, E.; Karalis, T.; Chatzistamatiou, K.; Theodoulidis, V.; Topalidou, M.; Timotheadou, E.; Grimbizis, G.; Tsolakidis, D. Prognostic Factors in the Treatment of Advanced Endometrial Cancer Patients: 12-Year Experience of an ESGO Certified Center. Cancers 2026, 18, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020343

Zouzoulas D, Sofianou I, Markopoulou E, Karalis T, Chatzistamatiou K, Theodoulidis V, Topalidou M, Timotheadou E, Grimbizis G, Tsolakidis D. Prognostic Factors in the Treatment of Advanced Endometrial Cancer Patients: 12-Year Experience of an ESGO Certified Center. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020343

Chicago/Turabian StyleZouzoulas, Dimitrios, Iliana Sofianou, Efthalia Markopoulou, Tilemachos Karalis, Kimon Chatzistamatiou, Vasilis Theodoulidis, Maria Topalidou, Eleni Timotheadou, Grigoris Grimbizis, and Dimitrios Tsolakidis. 2026. "Prognostic Factors in the Treatment of Advanced Endometrial Cancer Patients: 12-Year Experience of an ESGO Certified Center" Cancers 18, no. 2: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020343

APA StyleZouzoulas, D., Sofianou, I., Markopoulou, E., Karalis, T., Chatzistamatiou, K., Theodoulidis, V., Topalidou, M., Timotheadou, E., Grimbizis, G., & Tsolakidis, D. (2026). Prognostic Factors in the Treatment of Advanced Endometrial Cancer Patients: 12-Year Experience of an ESGO Certified Center. Cancers, 18(2), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020343