Fitness in CLL

Simple Summary

Abstract

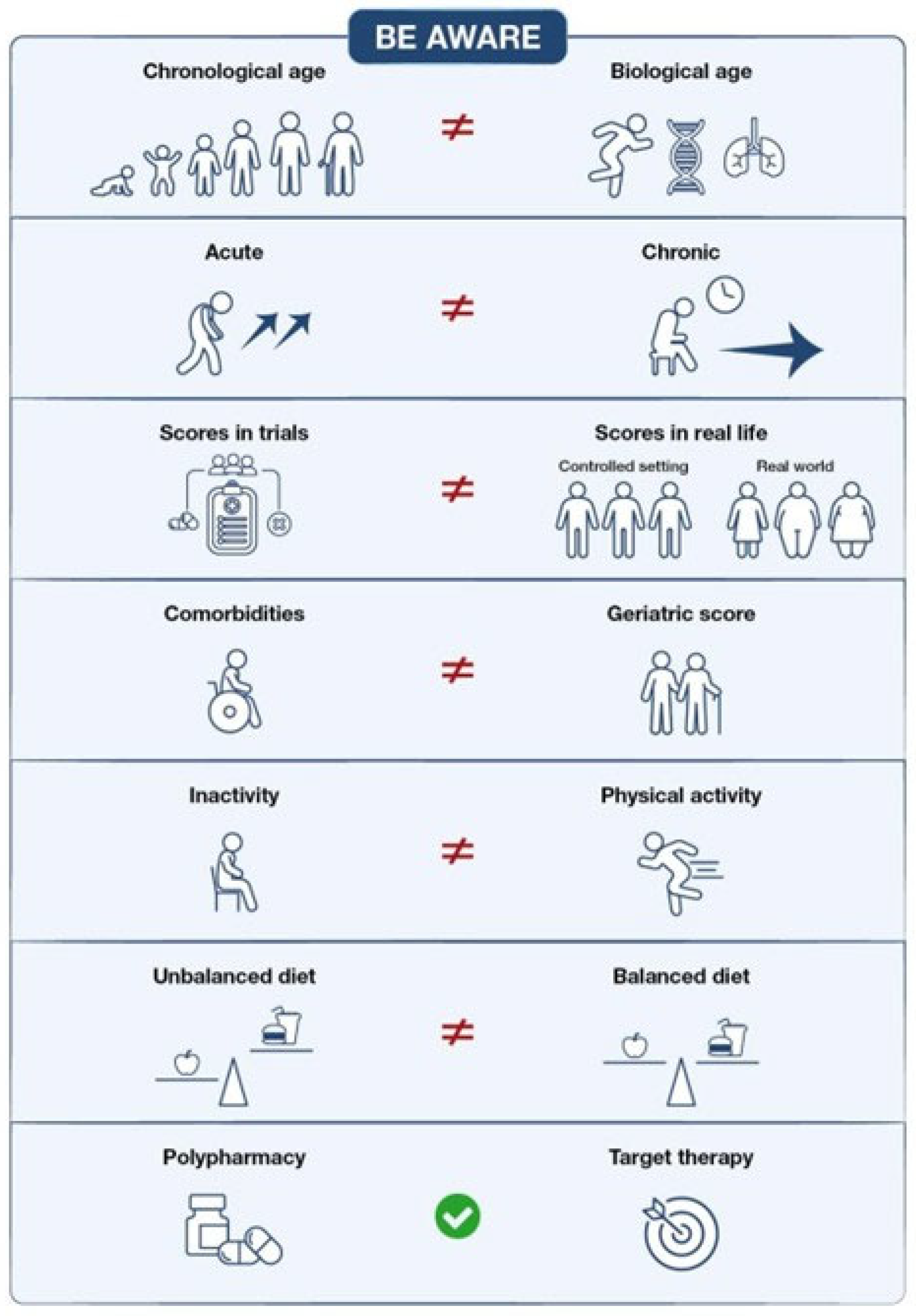

1. Introduction

2. Fitness in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Transferable Lessons for CLL?

3. The Role of Age in Defining Fitness

4. Limits of Comorbidities Score Systems: How to Cross Them to Redefine Fitness

5. Do the Guidelines Actualize the Concept of Fitness?

6. Polypharmacy and Drug Interactions: Is It an Outdated Concept?

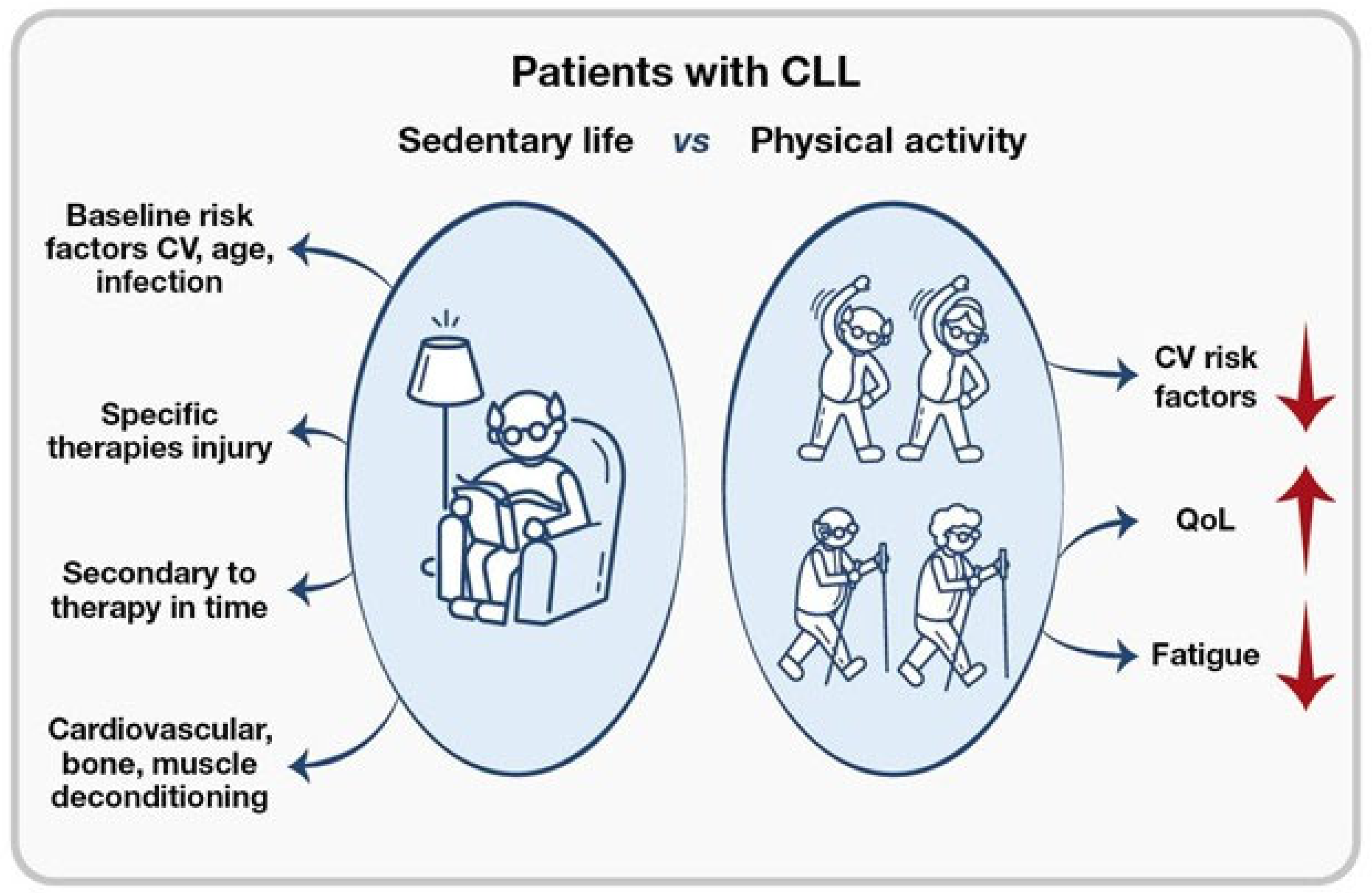

7. Role of Exercise in Redefining Fitness and the Figure of the Kinesiologist

8. Nutrition and the Role of the Nutritionist in Redefining Fitness

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BTK | Bruton Tyrosine Kinase |

| CI | Comorbidity Index |

| CLL | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| DDI | Drug–Drug Interaction |

| EFS | Event-Free Survival |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PFS | Progression-Free Survival |

References

- Wierda, W.G.; Brown, J.; Abramson, J.S.; Awan, F.; Bilgrami, S.F.; Bociek, G.; Brander, D.; Chanan-Khan, A.A.; Coutre, S.E.; Davis, R.S.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma, Version 3.2022. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2022, 20, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichhorst, B.; Robak, T.; Montserrat, E.; Ghia, P.; Niemann, C.U.; Kater, A.P.; Gregor, M.; Cymbalista, F.; Buske, C.; Hillmen, P.; et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorst, B.; Ghia, P.; Niemann, C.U.; Kater, A.P.; Gregor, M.; Hallek, M.; Jerkeman, M.; Buske, C.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline interim update on new targeted therapies in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotbain, E.C.; Niemann, C.U.; Rostgaard, K.; da Cunha-Bang, C.; Hjalgrim, H.; Frederiksen, H. Mapping comorbidity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Impact of individual comorbidities on treatment, mortality, and causes of death. Leukemia 2021, 35, 2570–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, F.; Miller, M.D.; Grilli, A.; Giorgi, R.; Towers, A.L.; Morichi, V.; Spazzafumo, L.; Mancinelli, L.; Espinosa, E.; Rappelli, A.; et al. A manual of guidelines to score the modified cumulative illness rating scale and its validation in acute hospitalized elderly patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 1926–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oken, M.M.; Creech, R.H.; Tormey, D.C.; Horton, J.; Davis, T.E.; McFadden, E.T.; Carbone, P.P. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 1982, 5, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.A.; Tedeschi, A.; Barr, P.M.; Robak, T.; Owen, C.; Ghia, P.; Bairey, O.; Hillmen, P.; Bartlett, N.L.; Li, J.; et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2425–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.; Al-Sawaf, O.; Bahlo, J.; Fink, A.M.; Tandon, M.; Dixon, M.; Robrecht, S.; Warburton, S.; Humphrey, K.; Samoylova, O.; et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2225–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, A.; Frustaci, A.M.; Mauro, F.R.; Chiarenza, A.; Coscia, M.; Ciolli, S.; Reda, G.; Laurenti, L.; Varettoni, M.; Murru, R.; et al. Do age, fitness, and concomitant medications influence management and outcomes of patients with CLL treated with ibrutinib? Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 5490–5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditti, A.; Palmieri, R.; Maurillo, L.; Röllig, C.; Wierzbowska, A.; de Leeuw, D.; Efficace, F.; Curti, A.; Ngai, L.L.; Tettero, J.; et al. Fitness assessment in acute myeloid leukemia: Recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 2207–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, F.; Barosi, G.; Venditti, A.; Angelucci, E.; Gobbi, M.; Pane, F.; Tosi, P.; Zinzani, P.; Tura, S. Consensus-based definition of unfitness to intensive and non-intensive chemotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2013, 27, 997–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidori, A.; Loscocco, F.; Visani, G. AML therapy in the elderly: A time for a change. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2016, 15, 891–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmieri, R.; Maurillo, L.; Del Principe, M.I.; Paterno, G.; Walter, R.B.; Venditti, A.; Buccisano, F. Time for dynamic assessment of fitness in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers 2022, 15, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataguba, J.E.; Bloom, D.E.; Scott, K.A. The Global Aging Challenge and the Health Care Sector: The 21st Century’s Social and Economic Transformation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson, M.; Sandin, F.; Kimby, E.; Höglund, M.; Glimelius, I. Increasing prevalence of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with an estimated future rise. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, E36–E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorst, B.; Hallek, M.; Goede, V. Management of unfit elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 58, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallarico, M. Toxicities and related outcomes of elderly patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood 2016, 128, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, K.; Song, X.; MacKnight, C.; Bergman, H.; Hogan, D.B.; McDowell, I.; Mitnitski, A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gascon, Y.M.I.; Ballesteros-Andres, M.; Martinez-Flores, S.; Rodriguez-Vicente, A.E.; Perez-Carretero, C.; Quijada-Alamo, M.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, A.; Hernández-Rivas, J.Á. The five “Ws” of frailty assessment and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancers 2023, 15, 4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; van Wijngaarden, E.; Seplaki, C.L.; Heckler, C.E.; Weber, M.T.; Barr, P.M.; Zent, C.S. Cognitive function in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2020, 61, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolin, G.M.; Cavallari, M.; Quaglia, F.M.; Formigaro, L.; Lista, E.; Urso, A.; Guardalben, E.; Liberatore, C.; Faraci, D.; Saccenti, E.; et al. Comorbidities and complex karyotype are associated with inferior outcome in CLL. Blood 2017, 129, 3495–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauder, R.; Eichhorst, B.; Hamaker, M.E.; Kaplanov, K.; Morrison, V.A.; Osterborg, A.; Poddubnaya, I.; Woyach, J.A.; Shanafelt, T.; Smolej, L.; et al. Management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in the elderly: A position paper from an international Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Task Force. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, M.J.; Kaempf, A.; Sitlinger, A.; Shouse, G.; Mei, M.; Brander, D.M.; Salous, T.; Hill, B.T.; Alqahtani, H.; Choi, M.; et al. The Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Comorbidity Index (CLL-CI): A Three-Factor Comorbidity Model. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4814–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotbain, E.C.; Gordon, M.J.; Vainer, N.; Frederiksen, H.; Hjalgrim, H.; Danilov, A.V.; Niemann, C.U. The CLL comorbidity index in a population-based cohort. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 2701–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, K.; Bahlo, J.; Fink, A.M.; Goede, V.; Herling, C.D.; Cramer, P.; Langerbeins, P.; von Tresckow, J.; Engelke, A.; Maurer, C.; et al. Long-term remissions after FCR chemoimmunotherapy: Updated results of the CLL8 trial. Blood 2016, 127, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojdeman, F.J.; Van’t Veer, M.B.; Tjonnfjord, G.E.; Itala-Remes, M.; Kimby, E.; Polliack, A.; Wu, K.L.; Doorduijn, J.K.; Alemayehu, W.G.; Wittebol, S.; et al. The HOVON68 CLL trial revisited: Performance status and comorbidity affect survival in elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2017, 58, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goede, V.; Bahlo, J.; Chataline, V.; Eichhorst, B.; Durig, J.; Stilgenbauer, S.; Kolb, G.; Honecker, F.; Wedding, U.; Hallek, M. Evaluation of geriatric assessment in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results of the CLL9 trial of the German CLL study group. Leuk. Lymphoma 2016, 57, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaker, M.E.; Mitrovic, M.; Stauder, R. The G8 screening tool detects relevant geriatric impairments and predicts survival in elderly patients with a hematological malignancy. Ann. Hematol. 2014, 93, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goede, V.; Cramer, P.; Busch, R.; Bergmann, M.; Stauch, M.; Hopfinger, G.; Stilgenbauer, S.; Döhner, H.; Westermann, A.; Wendtner, C.M.; et al. Interactions between comorbidity and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results of German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group trials. Haematologica 2014, 99, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharman, J.P.; Egyed, M.; Jurczak, W.; Skarbnik, A.; Pagel, J.M.; Flinn, I.W.; Kamdar, M.; Munir, T.; Walewska, R.; Corbett, G.; et al. Acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil and obinutuzumab for treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukemia (ELEVATE TN): A randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurmes, P.; Call, T.; Slager, S.; Zent, C.; Jenkins, G.; Schwager, S.; Bowen, D.; Kay, N.; Shanafelt, T. Comorbid conditions and survival in unselected, newly diagnosed patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2008, 49, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michallet, A.S.; Cazin, B.; Bouvet, E.; Oberic, L.; Schlaifer, D.; Mosser, L.; Salles, G.; Coiffier, B.; Laurent, G.; Ysebaert, L. First immunochemotherapy outcomes in elderly patients with CLL: A retrospective analysis. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2013, 4, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crooks, V.; Waller, S.; Smith, T.; Hahn, T.J. The use of the Karnofsky Performance Scale in geriatric outpatients. J. Gerontol. 1991, 46, M139–M144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorst, B.; Fink, A.M.; Bahlo, J.; Busch, R.; Kovacs, G.; Maurer, C.; Lange, E.; Köppler, H.; Kiehl, M.; Sökler, M.; et al. First-line chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine and rituximab versus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL10): An international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goede, V.; Fischer, K.; Busch, R.; Engelke, A.; Eichhorst, B.; Wendtner, C.M.; Lange, E.; Köppler, H.; Kiehl, M.; Sökler, M.; et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmen, P.; Robak, T.; Janssens, A.; Babu, K.G.; Kloczko, J.; Grosicki, S.; Doubek, M.; Panagiotidis, P.; Kimby, E.; Schuh, A.; et al. Chlorambucil plus ofatumumab versus chlorambucil alone in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (COMPLEMENT 1): A randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 1873–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kater, A.P.; Owen, C.; Moreno, C.; Follows, G.; Munir, T.; Levin, M.D.; Benjamini, O.; Janssens, A.; Osterborg, A.; Robak, T.; et al. Fixed-Duration Ibrutinib-Venetoclax in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Comorbidities. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, C.S.; Brown, J.R.; Kahl, B.S.; Ghia, P.; Giannopoulos, K.; Jurczak, W.; Šimkovič, M.; Shadman, M.; Österborg, A.; Laurenti, L.; et al. Zanubrutinib versus bendamustine and rituximab in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SEQUOIA): A randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1031–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorst, B.; Niemann, C.U.; Kater, A.P.; Furstenau, M.; von Tresckow, J.; Zhang, C.; Robrecht, S.; Gregor, M.; Juliusson, G.; Thornton, P.; et al. First-Line Venetoclax Combinations in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1739–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, C.S.; Allan, J.N.; Siddiqi, T.; Kipps, T.J.; Jacobs, R.; Opat, S.; Barr, P.M.; Tedeschi, A.; Trentin, L.; Bannerji, R.; et al. Fixed-duration ibrutinib plus venetoclax for first-line treatment of CLL: Primary analysis of the CAPTIVATE FD cohort. Blood 2022, 139, 3278–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Seymour, J.F.; Jurczak, W.; Aw, A.; Wach, M.; Illes, A.; Tedeschi, A.; Owen, C.; Skarbnik, A.; Lysak, D.; et al. Fixed-Duration Acalabrutinib Combinations in Untreated Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sawaf, O. The Impact of Fitness and Dose Intensity on Safety and Efficacy Outcomes after Venetoclax-Obinutuzumab in Previously Untreated Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 2023, 142, 4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolin, G.M.; Olimpieri, P.P.; Summa, V.; Celant, S.; Scarfò, L.; Ballardini, M.P.; Urso, A.; Gambara, S.; Cavazzini, F.; Ghia, P.; et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in 3306 patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib outside of clinical trials: A nationwide study. Hemasphere 2024, 8, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winqvist, M.; Asklid, A.; Andersson, P.O.; Karlsson, K.; Karlsson, C.; Lauri, B.; Lundin, J.; Mattsson, M.; Norin, S.; Sandstedt, A.; et al. Real-world results of ibrutinib in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Data from 95 consecutive patients treated in a compassionate use program. Haematologica 2016, 101, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.J.; Churnetski, M.; Alqahtani, H.; Rivera, X.; Kittai, A.; Amrock, S.M.; James, S.; Hoff, S.; Manda, S.; Spurgeon, S.E.; et al. Comorbidities predict inferior outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Cancer 2018, 124, 3192–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frustaci, A.M.; Del Poeta, G.; Visentin, A.; Sportoletti, P.; Fresa, A.; Vitale, C.; Murru, R.; Chiarenza, A.; Sanna, A.; Mauro, F.R.; et al. Coexisting conditions and concomitant medications do not affect venetoclax management and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2022, 13, 20406207221127550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goede, V. Evaluation of the International Prognostic Index for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL-IPI) in elderly patients with comorbidities: Analysis of the CLL11 study population. Blood 2016, 128, 4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molica, S.; Giannarelli, D.; Levato, L.; Mirabelli, R.; Levato, D.; Lentini, M.; Piro, E. A simple score based on geriatric assessment predicts survival in elderly newly diagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Leuk. Lymphoma 2019, 60, 845–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurria, A.; Togawa, K.; Mohile, S.G.; Owusu, C.; Klepin, H.D.; Gross, C.P.; Lichtman, S.M.; Gajra, A.; Bhatia, S.; Katheria, V.; et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3457–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.C.; Woyach, J.A.; Ulrich, A.; Marcotte, V.; Nipp, R.D.; Lage, D.E.; Nelson, A.M.; Newcomb, R.A.; Rice, J.; Lavoie, M.W.; et al. Geriatric assessment measures are predictive of outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2023, 14, 101538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprahamian, I.; Cezar, N.O.C.; Izbicki, R.; Lin, S.M.; Paulo, D.L.V.; Fattori, A.; Biella, M.M.; Jacob Filho, W.; Yassuda, M.S. Screening for frailty with the FRAIL scale: A comparison with the phenotype criteria. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F. Efficacy and safety of acalabrutinib treatment in very old (≥80 years) and/or frail patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Primary endpoint analysis of the phase II CLL-Frail trial. Blood 2024, 144, 4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strati, P.; Parikh, S.A.; Chaffee, K.G.; Kay, N.E.; Call, T.G.; Achenbach, S.J.; Cerhan, J.R.; Slager, S.L.; Shanafelt, T.D. Relationship between comorbidities at diagnosis, survival and ultimate cause of death in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: A prospective cohort study. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 178, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frustaci, A.M.; Deodato, M.; Zamprogna, G.; Cairoli, R.; Montillo, M.; Tedeschi, A. SOHO state of the art updates and next questions: What is fitness in the era of targeted agents? Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022, 22, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha-Bang, C.; Geisler, C.H.; Enggaard, L.; Poulsen, C.B.; de Nully Brown, P.; Frederiksen, H.; Bergmann, O.J.; Pulczynski, E.J.; Pedersen, R.S.; Nielsen, L.H.; et al. The Danish National Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Registry. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 8, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulas, M.F.; Abete, C.; Pulisci, D.; Pani, A.; Massidda, B.; Dessì, S.; Mandas, A. Cholesterol esters as growth regulators of lymphocytic leukaemia cells. Cell Prolif. 2011, 44, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T. Ibrutinib and rituximab provides superior clinical outcome compared to FCR in younger patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Extended follow-up from the E1912 trial. Blood 2019, 134, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strati, P.; Nasr, S.H.; Leung, N.; Hanson, C.A.; Chaffee, K.G.; Schwager, S.M.; Achenbach, S.J.; Call, T.G.; Parikh, S.A.; Ding, W.; et al. Renal complications in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis: The Mayo Clinic experience. Haematologica 2015, 100, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A. Metabolic pathways in obesity-related breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, G.; Zaccari, P.; Rocco, G.; Scalese, G.; Panetta, C.; Porowska, B.; Pontone, S.; Severi, C. Proton pump inhibitors and dysbiosis: Current knowledge and aspects to be clarified. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 2706–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelwyn, G.J.; Newman, A.A.C.; Afonso, M.S.; van Solingen, C.; Corr, E.M.; Brown, E.J.; Albers, K.B.; Yamaguchi, N.; Narke, D.; Schlegel, M.; et al. Myocardial infarction accelerates breast cancer via innate immune reprogramming. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1452–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbbVie, Inc. Venclexta (Venetoclax): U.S. Prescribing Information; AbbVie: North Chicago, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, J.; Skee, D.; Murphy, J.; Sukbuntherng, J.; Hellemans, P.; Smit, J.; de Vries, R.; Jiao, J.J.; Snoeys, J.; Mannaert, E. Effect of CYP3A perpetrators on ibrutinib exposure in healthy participants. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2015, 3, e00156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zwart, L.; Snoeys, J.; de Jong, J.; Sukbuntherng, J.; Mannaert, E.; Monshouwer, M. Ibrutinib dosing strategies based on interaction potential of CYP3A4 perpetrators using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 100, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnes, H.D.; Chaffee, K.G.; Call, T.G.; Ding, W.; Kenderian, S.S.; Bowen, D.A.; Conte, M.; McCullough, K.B.; Merten, J.A.; Bartoo, G.T.; et al. Pharmacovigilance during ibrutinib therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma in routine clinical practice. Leuk. Lymphoma 2017, 58, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; DiNardo, C.D.; Potluri, J.; Dunbar, M.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Humerickhouse, R.A.; Wong, S.L.; Menon, R.M.; Konopleva, M.Y.; Salem, A.H.; et al. Management of venetoclax–posaconazole interaction in acute myeloid leukemia patients: Evaluation of dose adjustments. Clin. Ther. 2017, 39, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Salem, A.H.; Danilov, A.V.; Hu, B.; Puvvada, S.; Gutierrez, M.; Chien, D.; Lewis, L.D.; Wong, S.L. Effect of ketoconazole, a strong CYP3A inhibitor, on the pharmacokinetics of venetoclax in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, P.; Gandhi, V.V.; Keating, M.J. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of ibrutinib for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Rationale for lower doses. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2016, 12, 1381–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, S.; Tang, Z.; Novotny, W.; Tawashi, M.; Li, T.K.; Ou, Y.; Sahasranaman, S. Effect of rifampin and itraconazole on the pharmacokinetics of zanubrutinib in Asian and non-Asian healthy subjects. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2020, 85, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggin, J. What is physical activity? A holistic definition for teachers, researchers and policy makers. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, B.B.; Hergenroeder, A.L.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Lee, I.M.; Jakicic, J.M. Definition, measurement, and health risks associated with sedentary behavior. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thivel, D.; Tremblay, A.; Genin, P.M.; Panahi, S.; Rivière, D.; Duclos, M. Physical activity, inactivity, and sedentary behaviors: Definitions and implications in occupational health. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista-Ferreira, L.; Sandy, D.D.; Silva, P.; Medeiros-Lima, D.J.M.; Rodrigues, B.M. Impact of active breaks on sedentary behavior and perception of productivity in office workers. Rev. Bras. Med. Trab. 2024, 22, e20231213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, F. Impact of the new professional profile of the preventive and adapted physical activities kinesiologist on internal stakeholders. Acta Kinesiol. 2023, 17, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitlinger, A.; Brander, D.M.; Bartlett, D.B. Impact of exercise on the immune system and outcomes in hematologic malignancies. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courneya, K.S.; Sellar, C.M.; Stevinson, C.; McNeely, M.L.; Peddle, C.J.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Tankel, K.; Basi, S.; Chua, N.; Mazurek, A.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of aerobic exercise on physical functioning and quality of life in lymphoma patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4605–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streckmann, F.; Kneis, S.; Leifert, J.A.; Baumann, F.T.; Kleber, M.; Ihorst, G.; Herich, L.; Grüssinger, V.; Gollhofer, A.; Bertz, H. Exercise program improves therapy-related side effects and quality of life in lymphoma patients undergoing therapy. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constans, T. Malnutrition in the elderly. Rev. Prat. 2003, 53, 275–279. [Google Scholar]

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A.M.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Hooper, L.; Kiesswetter, E.; Maggio, M.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Sieber, C.C.; Sobotka, L.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 958–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosetti, C.; Casirati, A.; Da Prat, V.; Masi, S.; Crotti, S.; Ferrari, A.; Perrone, L.; Serra, F.; Santucci, C.; Cereda, E.; et al. Multicentric observational longitudinal study on nutritional management in newly diagnosed Italian cancer patients (IRMO). BMJ Open 2023, 13, e071858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscaritoli, M. Linea Guida Pratica ESPEN: Nutrizione Clinica Nel Cancro; ESPEN: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A.M.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Goisser, S.; Hooper, L.; Kiesswetter, E.; Maggio, M.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Sieber, C.C.; et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 10–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieber, C.C. Malnutrition and sarcopenia. Aging. Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 31, 793–798. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, F.; Calvani, R.; Cesari, M.; Tosato, M.; Martone, A.M.; Ortolani, E.; Savera, G.; Salini, S.; Sisto, A.; Picca, A.; et al. Sarcopenia: An Overview on Current Definitions, Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2018, 19, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlidou, E.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Fasoulas, A.; Papaliagkas, V.; Alexatou, O.; Chatzidimitriou, M.; Mentzelou, M.; Giaginis, C. Diabesity and dietary interventions: Evaluating the impact of Mediterranean diet and other diets on obesity and type 2 diabetes management. Nutrients 2023, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Barquero, S.; Ruiz-León, A.M.; Sierra-Pérez, M.; Estruch, R.; Casas, R. Dietary strategies for metabolic syndrome: A comprehensive review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, G.O.; Torrinhas, R.S.; Waitzberg, D.L. Nutrients, physical activity, and mitochondrial dysfunction in the setting of metabolic syndrome. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, F.T.; Addison, D.; Alfraih, F.; Baratta, S.J.; Campos, R.N.; Cugliari, M.S.; Goh, Y.T.; Ionin, V.A.; Mundnich, S.; Sverdlov, A.L.; et al. International consensus statement on the management of cardiovascular risk of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors in CLL. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 5516–5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Gonçalves Dos Santos, J.; de Farias Meirelles, B.; de Souza da Costa Brum, I.; Zanchetta, M.; Xerem, B.; Braga, L.; Haiut, M.; Lanziani, R.; Musa, T.H.; Cordovil, K. First clinical nutrition outpatient consultation: Basic principles in nutritional care of adults with hematologic disease. Sci. World J. 2023, 2023, 9303798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Delgado, J.C.; Patel, J.J.; Stoppe, C.; McClave, S.A. Considerations for medical nutrition therapy management of the critically ill patient with hematological malignancies: A narrative review. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2024, 39, 800–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prognostic Score | Organ Assessment | Time- Consuming | Prospective Validation | CLL Setting | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale | CIRS | 14 | Yes | Yes | Yes | [5,22,23] |

| CLL-Comorbidity Index | CLL-CI | 3 | No | No | Yes | [4,24,25] |

| Creatinine/Clearance | CrCL | 1 | No | No | Yes | [33,34] |

| Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment | CGA | 13 | Yes | No | Yes | [28,29] |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | CCI | 18 | Yes | No | Yes | [30,31,32] |

| Trial | Inclusion Criteria | Patient Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| RESONATE2 Ibrutinib arm [7] | Over 65 years ECOG PS 0–2 | Median Age 73 years (65–89) ECOG PS 0–1 92% CIRS > 6 31% CrCl < 60 44% |

| ELEVATE-TN Acalabrutinib arm [31] | Over 65 years or Under 65 with CIRS > 6 or Under 65 with CrCl 30–69 mL/min PS 0–2 Significant cardiovascular disease excluded | Median Age 70 years (66–75) ECOG PS 0–1 92.2% CIRS > 6 11.7% CrCl < 70 2.2% |

| SEQUOIA Zanubrutinib arm [39] | Unfit for FCR: Over 65 years or Under 65 with CIRS > 6 or Under 65 with CrCl 30–69 mL/min | Median Age 70 years (40–86) ECOG PS 0–1 94% CIRS > 6 26.4% |

| CLL14 Ven-O arm [8] | CIRS > 6 or CrCl < 70 mL/min | Median Age 72 years (43–89) ECOG PS 0–1 87% CIRS > 6 86% CrCl < 70 59.5% |

| CLL13 Ven-O arm [40] | CIRS ≤ 6 CrCL ≥ 70 mL/min ECOG PS 0–2 | Median Age 62 years (31–85) ECOG PS 0 72% CIRS > 6 0% Median CrCl 86.3 (41.5–180.2) |

| GLOW Ibrutinib–venetoclax [38] | Over 65 years or Under 65 with CIRS > 6 or Under 65 with CrCl < mL/min ECOG PS 0–2 | Median Age years 71 (47–91) ECOG PS 0 33% CIRS > 6 69.8% Median CrCl 66.5 (34.0–168.1) |

| CAPTIVATE-FD Ibrutinib–venetoclax [41] | Under 70 years ECOG PS 0–1 | Median Age 60 years (33–71) ECOG PS 0–1 100% |

| AMPLIFY [42] acalabrutinib–venetoclax–obinutuzumab | ECOG PS 0–2 | Median age 61 years |

| BTK Inhibitors | Ibrutinib | Acalabrutinib | Zanubrutinib |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong CY3A4 INHIBITORS | Interrupt dose | Interrupt dose | May reduce dose to 80 mg/bid |

| Moderate CY3A4 INHIBITORS | 280 mg of 140 mg/die up to 70 mg/die (high dose) | 100 mg/die | 80 mg/bid |

| Mild CY3A4 INHIBITORS | No change | No change | No change |

| Strong CY3A4 INDUCERS | Avoid concomitant use | Increase dose by 200 mg × 2/die | Avoid concomitant use |

| Moderate CY3A4 INDUCERS | No indications | No indications | No indications |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Baratè, C.; Scortechini, I.; Ciofini, S.; Picardi, P.; Angeletti, I.; Loscocco, F.; Sanna, A.; Isidori, A.; Grazioli, E.; Sportoletti, P. Fitness in CLL. Cancers 2026, 18, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020342

Baratè C, Scortechini I, Ciofini S, Picardi P, Angeletti I, Loscocco F, Sanna A, Isidori A, Grazioli E, Sportoletti P. Fitness in CLL. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020342

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaratè, Claudia, Ilaria Scortechini, Sara Ciofini, Paola Picardi, Ilaria Angeletti, Federica Loscocco, Alessandro Sanna, Alessandro Isidori, Elisa Grazioli, and Paolo Sportoletti. 2026. "Fitness in CLL" Cancers 18, no. 2: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020342

APA StyleBaratè, C., Scortechini, I., Ciofini, S., Picardi, P., Angeletti, I., Loscocco, F., Sanna, A., Isidori, A., Grazioli, E., & Sportoletti, P. (2026). Fitness in CLL. Cancers, 18(2), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020342