Epidemiology of Primary Urethral Cancer: Insights from Four European Countries with a Focus on Poland

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Topographic Classification

2.3. Selection Criteria

2.4. Statistical Analysis

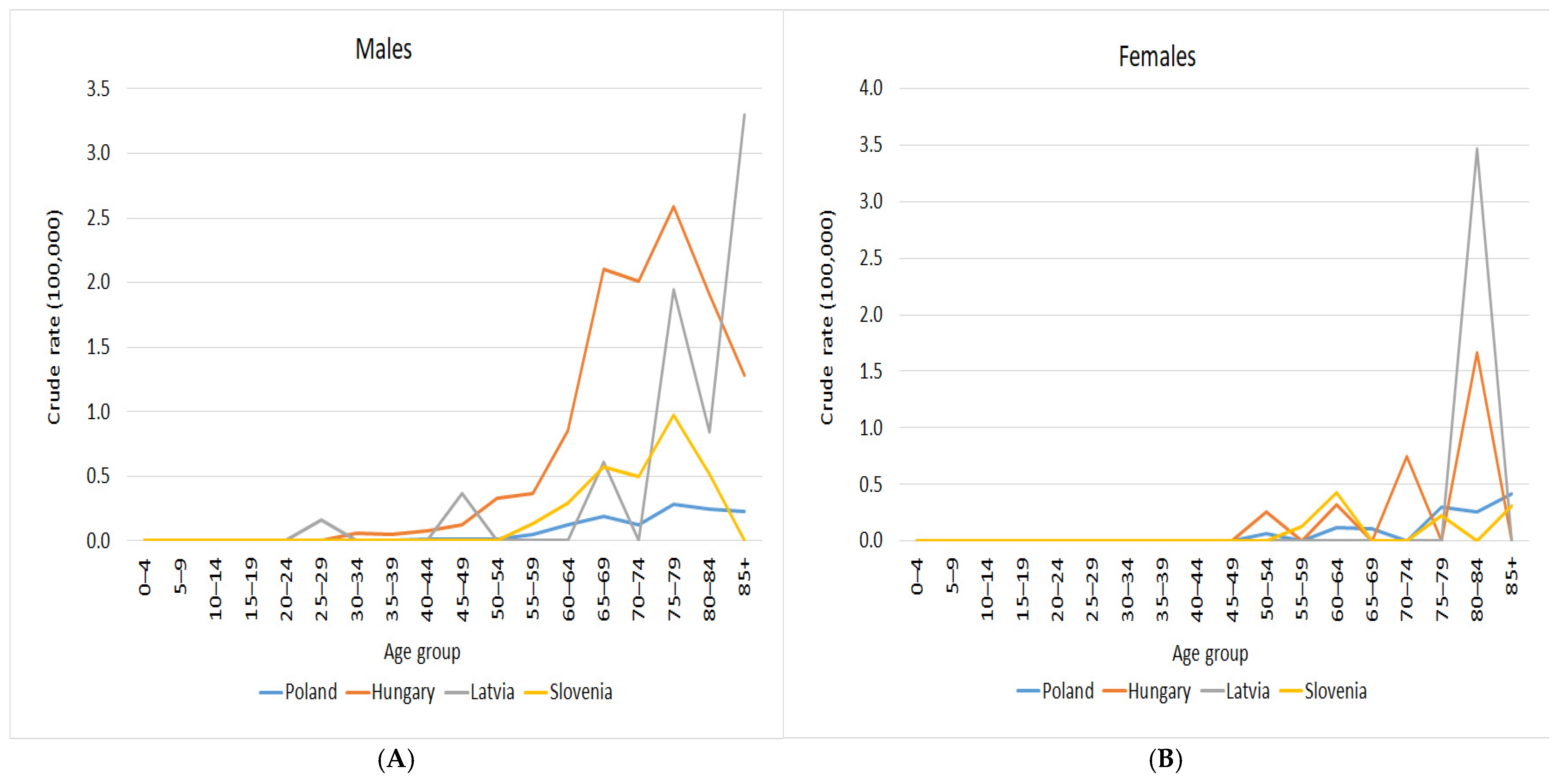

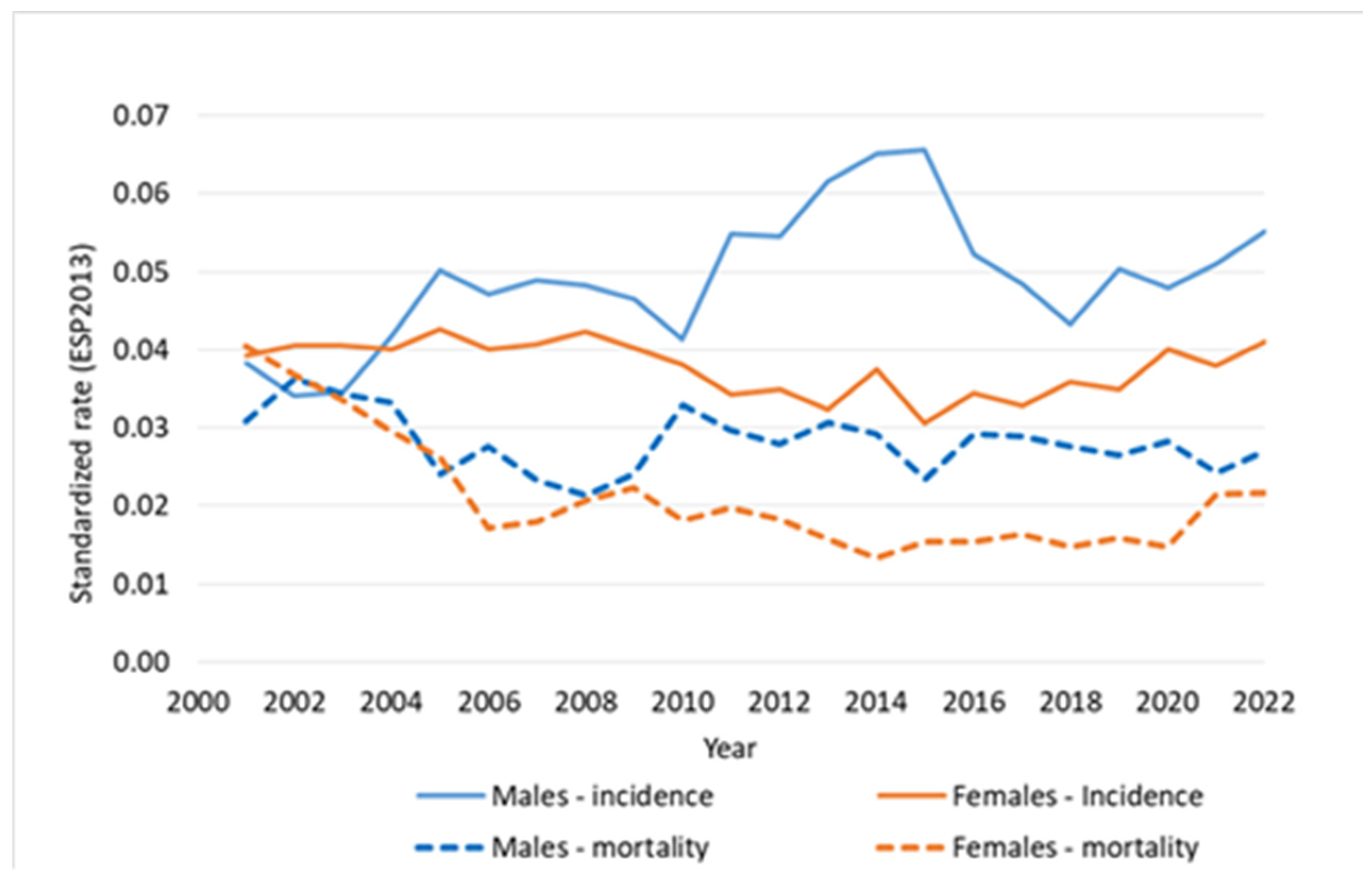

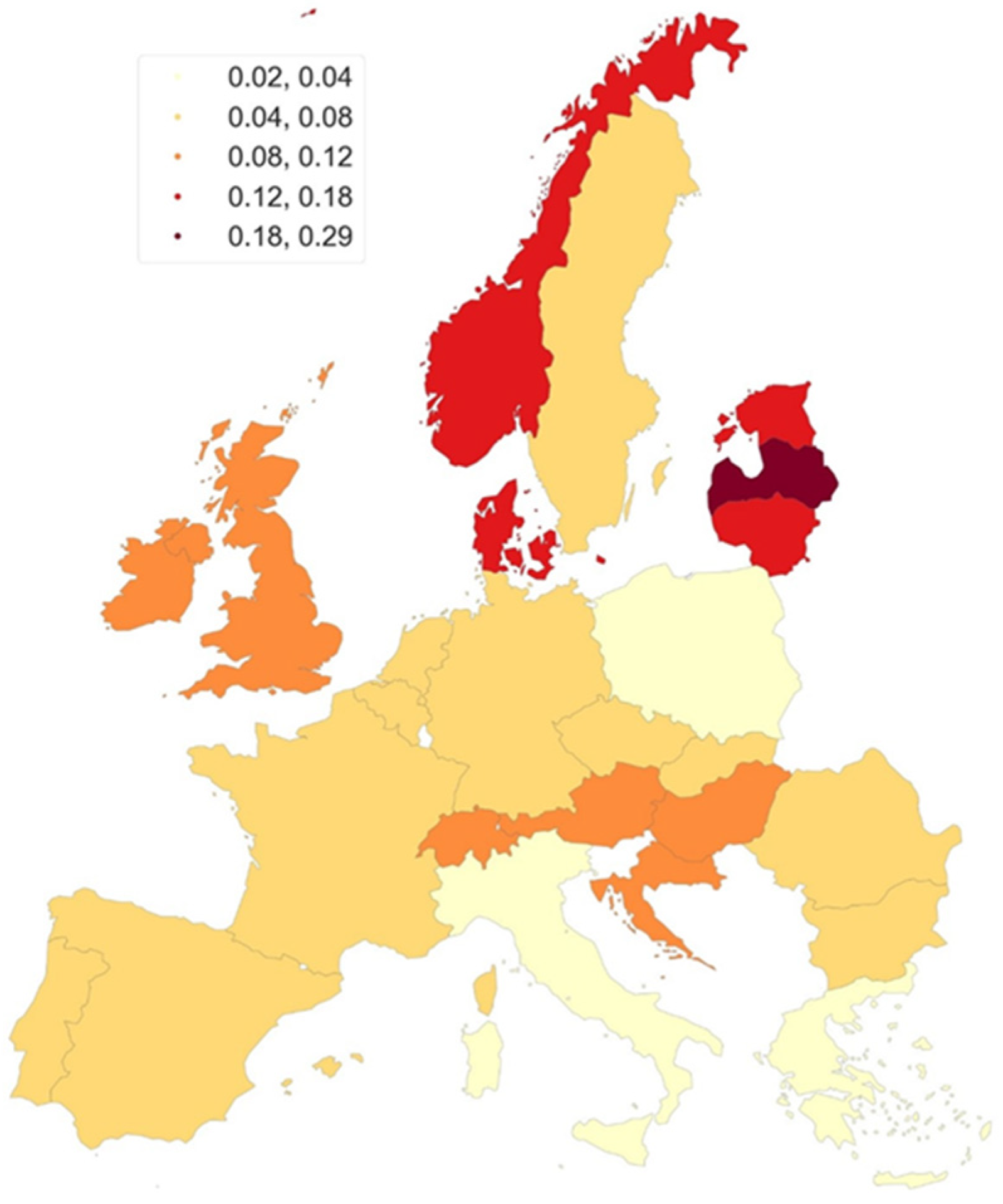

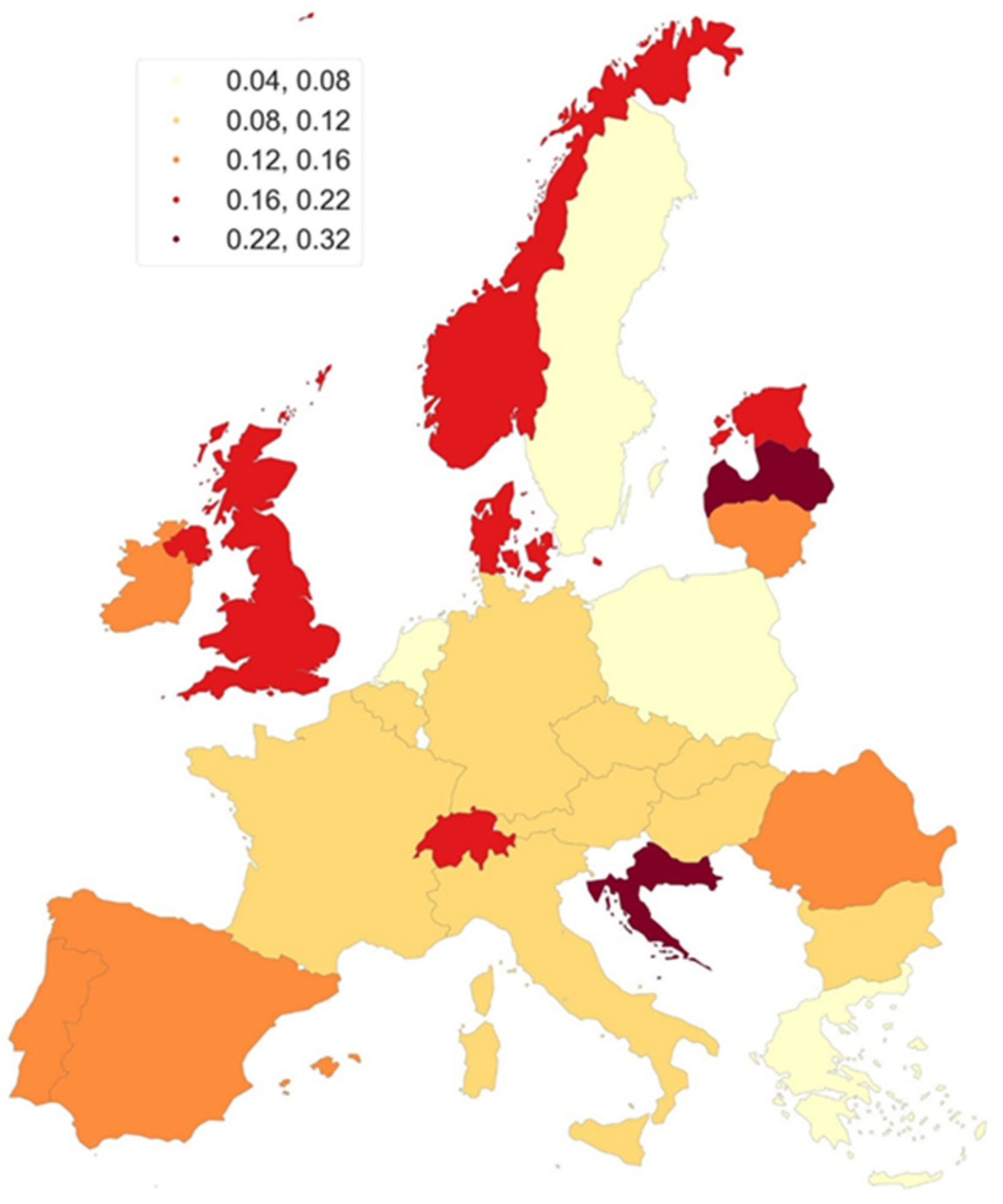

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Study Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Rare Diseases. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/research-area/health/rare-diseases_en (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- EAU Annual Congress. EAU Guidelines. In Proceedings of the Presented at the EAU Annual Congress, Madrid, Spain, 21–24 March 2025; ISBN 978-94-92671-29-5. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R.L. Urethral Cancer. Cancer 1980, 45, 1965–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, O.; Adolfsson, J.; Rossi, S.; Verne, J.; Gatta, G.; Maffezzini, M.; Franks, K.N.; Zielonk, N.; Van Eycken, E.; Sundseth, H.; et al. Incidence and survival of rare urogenital cancers in Europe. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Dasgupta, R.; Vats, A.; Nagpal, K.; Ashrafian, H.; Kaj, B.; Athanasiou, T.; Dasgupta, P.; Khan, M.S. Urethral diverticular carcinoma: An overview of current trends in diagnosis and management. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2010, 42, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayyani, F.; Hoffman, K.; Eifel, P.; Guo, C.; Vikram, R.; Pagliaro, L.C.; Pettaway, C. Management of advanced primary urethral carcinomas. BJU Int. 2014, 114, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawczuk, I.; Acosta, R.; Grant, D.; White, R.D. Post urethroplasty squamous cell carcinoma. N. Y. State J. Med. 1986, 86, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.A.; Reuter, V.; Scher, H.I. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate after radiation seed implantation for adenocarcinoma. Urology 1995, 46, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, J.S.; Liu, E.T.; Walther, P.J. Oncogenic human papillomavirus type 16 is associated with squamous cell cancer of the male urethra. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 5018–5023. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Peng, X.; Jin, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Sa, Y. Lichen Sclerosus Accompanied by Urethral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Study From a Urethral Referral Center. Am. J. Men’s Health 2018, 12, 1692–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Mortality Database. Data Downloaded as ZIP File. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/data-collection-tools/who-mortality-database (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Revision of the European Standard Population—Report of Eurostat’s Task Force—2013 Edition. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-manuals-and-guidelines/-/ks-ra-13-028 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Jenks, G.F. The Data Model Concept in Statistical Mapping. In International Yearbook of Cartography; George Philip: London, UK, 1967; pp. 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Fogarasi, A.I.; Benczik, M.; Moravcsik-Kornyicki, Á.; Kocsis, A.; Gyulai, A.; Kósa, Z. The Prevalence of High-Risk Human Papillomavirus in Hungary—A Geographically Representative, Cross-Sectional Study. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2022, 28, 1610424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUROSTAT. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Cancer_statistics (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Mihai, A. The Apparent Cancer Paradox of Latvia. Cancerworld Magazine. Available online: https://cancerworld.net/the-apparent-cancer-paradox-of-latvia (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Wenzel, M.; Nocera, L.; Collà Ruvolo, C.; Würnschimmel, C.; Tian, Z.; Shariat, S.F.; Saad, F.; Briganti, A.; Tilki, D.; Mandel, P.; et al. Sex-Related Differences Include Stage, Histology, and Survival in Urethral Cancer Patients. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2021, 19, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swartz, M.A.; Porter, M.P.; Lin, D.W.; Weiss, N.S. Incidence of primary urethral carcinoma in the United States. Urology 2006, 68, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, B.V.; Hill, S.C.; Moses, K.A. The effect of centralization of care on overall survival in primary urethral cancer. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2021, 39, 133.e17–133.e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.B.; Ray-Zack, M.D.; Hudgins, H.K.; Oldenburg, J.; Trinh, Q.D.; Nguyen, P.L.; Shore, N.D.; Wirth, M.P.; O’Brien, T.; Catto, J.W.F. Impact of centralizing care for genitourinary malignancies to high-volume providers: A systematic review. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2019, 2, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, M.; Li, R.; Pegler, K.; Sangar, V.; Kelly, J.D.; Minhas, S.; Muneer, A.; Coleman, M.P. Long-term trends in incidence, survival and mortality of primary penile cancer in England. Cancer Causes Control 2013, 24, 2169–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnętrzak, I.; Czajkowski, M.; Barańska, K.; Miklewska, M.; Wojciechowska, U.; Sosnowski, R.; Didkowska, J.A. Epidemiology of penile cancer in Poland compared to other European countries. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazevic, I.; Fléchon, A.; Pignot, G.; Mesnard, B.; Rigaud, J.; Roumiguié, M.; Soulié, M.; Thibault, C.; Crouzet, L.; Goislard De Monsabert, C.; et al. Primary urethral cancer: Treatment patterns, responses and survival in localized, advanced and metastatic patients. BJUI Compass 2025, 6, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.B.; Leder, R.A.; Inman, B.A. Imaging tumors of the penis and urethra. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 37, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaig, T.W.; Spiess, P.E.; Agarwal, N.; Bangs, R.; Boorjian, S.A.; Buyyounouski, M.K.; Chong, K.T.; Grossman, H.B.; Horwitz, E.M.; James, N.D.; et al. Bladder cancer, version 3.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avancès, C.; Lesourd, A.; Michel, F.; Mottet, N. Tumeurs primitives de l’urètre. Épidémiologie, diagnostic et anatomopathologie. Recommandations du comité de cancérologie de l’Association française d’urologie. Progrès Urol. 2009, 19, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gakis, G.; Morgan, T.M.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Keegan, K.A.; Mischinger, J.; Todenhoefer, T.; Schubert, T. Prognostic factors and outcomes in primary urethral cancer: Results from the international collaboration on primary urethral carcinoma. World J. Urol. 2016, 34, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, C.H.; Liauw, S.L.; Hasan, Y.; Solanki, A.A. Optimizing the role of surgery and radiation therapy in urethral cancer based on histology and disease extent. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2018, 102, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, R.; Vertosick, E.A.; Sarcona, J.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Benfante, N.E.; Donahue, T.F.; Hanna, N.; Tosoian, J.J.; Eggener, S.E.; Trudeau, V.; et al. Primary urethral cancer: Treatment patterns and associated outcomes. BJU Int. 2020, 126, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalbagni, G.; Zhang, Z.F.; Lacombe, L.; Herr, H.W. Female urethral carcinoma: An analysis of treatment outcome and a plea for a standardized management strategy. Br. J. Urol. 1998, 82, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, T.Y.; Naguib, M.; Galang, T.; Fuller, C.D. Retrospective study of the treatment of urethral cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 26, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gakis, G.; Morgan, T.M.; Daneshmand, S.; Keegan, K.A.; Todenhöfer, T.; Mischinger, J.; Schubert, T.; Zaid, H.B.; Hrbacek, J.; Ali-El-Dein, B.; et al. Impact of perioperative chemotherapy on survival in patients with advanced primary urethral cancer: Results of the international collaboration on primary urethral carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1754–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex | Country | Year | APC | Lower CI | Upper CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | HUN | 2001–2020 | 5.84 | 2.30 | 9.48 | <0.000001 |

| M | LAT | 2000–2017 | −1.52 | −9.99 | 7.73 | 0.681 |

| M | POL | 2000–2022 | 1.62 | −0.60 | 3.80 | 0.156 |

| M | SLO | 2000–2020 | −4.05 | −14.06 | 7.23 | 0.369 |

| F | HUN | 2001–2020 | 3.03 | −0.73 | 6.88 | 0.162 |

| F | LAT | 2000–2017 | −3.46 | −10.45 | 3.99 | 0.419 |

| F | POL | 2000–2022 | −0.42 | −2.10 | 1.26 | 0.543 |

| F | SLO | 2000–2020 | −4.50 | −19.60 | 13.27 | 0.585 |

| MF | HUN | 2001–2020 | 4.81 | 1.61 | 8.12 | <0.000001 |

| MF | LAT | 2000–2017 | −1.33 | −9.32 | 7.20 | 0.735 |

| MF | POL | 2000–2022 | 0.46 | −0.72 | 1.65 | 0.377 |

| MF | SLO | 2000–2020 | −3.19 | −13.38 | 8.08 | 0.466 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wnętrzak, I.; Wojciechowska, U.; Didkowska, J.A.; Dobruch, J.; Czajkowski, M.; Sosnowski, R. Epidemiology of Primary Urethral Cancer: Insights from Four European Countries with a Focus on Poland. Cancers 2026, 18, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020290

Wnętrzak I, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska JA, Dobruch J, Czajkowski M, Sosnowski R. Epidemiology of Primary Urethral Cancer: Insights from Four European Countries with a Focus on Poland. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020290

Chicago/Turabian StyleWnętrzak, Iwona, Urszula Wojciechowska, Joanna A. Didkowska, Jakub Dobruch, Mateusz Czajkowski, and Roman Sosnowski. 2026. "Epidemiology of Primary Urethral Cancer: Insights from Four European Countries with a Focus on Poland" Cancers 18, no. 2: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020290

APA StyleWnętrzak, I., Wojciechowska, U., Didkowska, J. A., Dobruch, J., Czajkowski, M., & Sosnowski, R. (2026). Epidemiology of Primary Urethral Cancer: Insights from Four European Countries with a Focus on Poland. Cancers, 18(2), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020290