High-Frequency Ultrasound Assessment of Basal Cell Carcinoma: Correlations Between Histopathological Subtype, Vascularity, and Age/Sex Distribution

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Histopathological Correlation

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

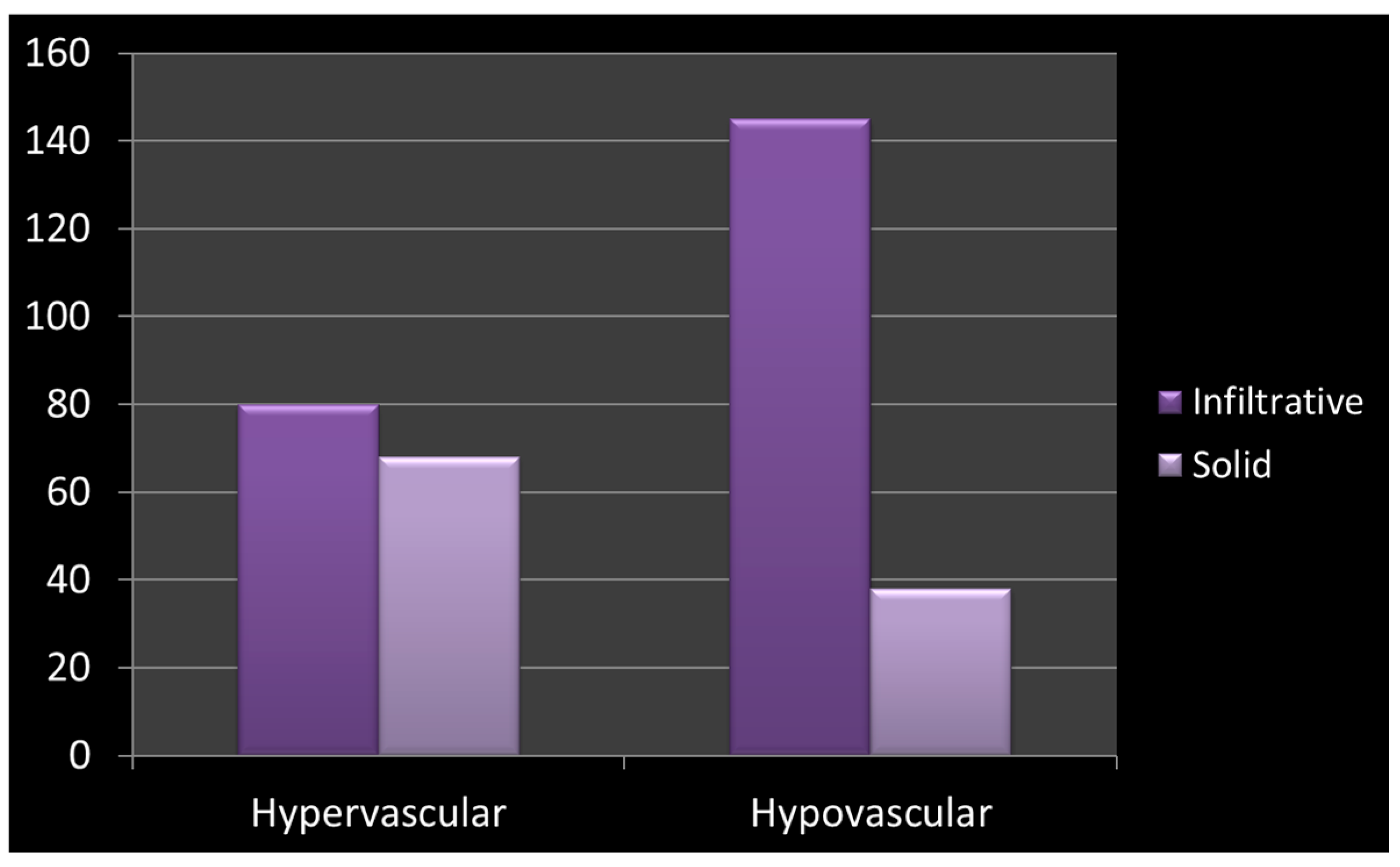

3.1. Morphology and Vascularity

3.2. Sex-Stratified Analysis

3.3. Age-Stratified Analysis

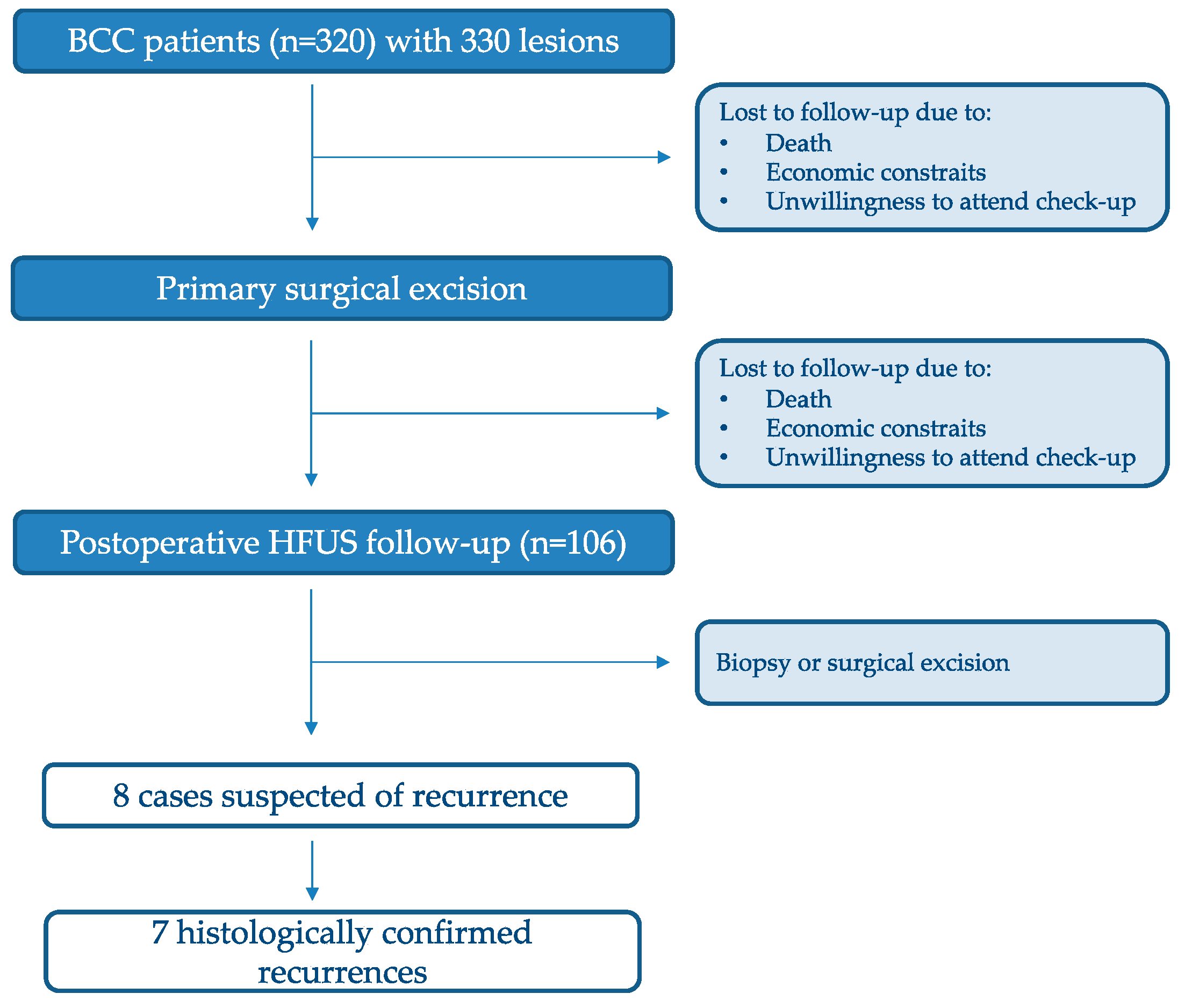

3.4. Recurrent Tumor Morphology and Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lai, V.; Cranwell, W.; Sinclair, R. Epidemiology of skin cancer in the mature patient. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 36, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallas, A.; Apalla, Z.; Argenziano, G.; Longo, C.; Moscarella, E.; Specchio, F.; Raucci, M.; Zalaudek, I. The dermatoscopic universe of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol. Pr. Concept. 2014, 4, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bungărdean, R.-M.; Şerbănescu, M.-S.; Colosi, H.A.; Crişan, M. High-frequency ultrasound: An essential non-invasive tool for the pre-therapeutic assessment of basal cell carcinoma. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2021, 62, 545–551. [Google Scholar]

- Csány, G.; Gergely, L.H.; Kiss, N.; Szalai, K.; Lőrincz, K.; Strobel, L.; Csabai, D.; Hegedüs, I.; Marosán-Vilimszky, P.; Füzesi, K.; et al. Preliminary Clinical Experience with a Novel Optical-Ultrasound Imaging Device on Various Skin Lesions. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 204. [Google Scholar]

- Wüstner, M.; Radzina, M.; Calliada, F.; Cantisani, V.; Havre, R.F.; Jenderka, K.-V.; Kabaalioğlu, A.; Kocian, M.; Kollmann, C.; Künzel, J.; et al. Professional Standards in Medical Ultrasound-EFSUMB Position Paper (Long Version)-General Aspects. Ultraschall Med. 2022, 43, e36–e48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alfageme, F.; Wortsman, X.; Catalano, O.; Roustan, G.; Crisan, M.; Crisan, D.; Gaitini, D.E.; Cerezo, E.; Badea, R. European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (EFSUMB) Position Statement on Dermatologic Ultrasound. Ultraschall Med. 2021, 42, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcaui, E.D.O.; Carvalho, A.C.P.; Lopes, F.P.P.L.; Piñeiro-Maceira, J.; Barcaui, C.B. High frequency ultrasound with color Doppler in dermatology. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2016, 91, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płocka, M.; Czajkowski, R. High-frequency ultrasound in the diagnosis and treatment of skin neoplasms. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2023, 40, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ibáñez, C.; Blazquez-Sánchez, N.; Aguilar-Bernier, M.; Fúnez-Liébana, R.; Rivas-Ruiz, F.; de Troya-Martín, M. Usefulness of High-Frequency Ultrasound in the Classification of Histologic Subtypes of Primary Basal Cell Carcinoma. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas (Engl. Ed.) 2017, 108, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajdeanu, I.-A.; Vata, D.; Statescu, L.; Popescu, I.A.; Porumb-Andrese, E.; Patrascu, A.I.; Stincanu, A.; Taranu, T.; Crisan, M.; Solovastru, L.G. Use of imaging techniques for melanocytic naevi and basal cell carcinoma in integrative analysis (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laverde-Saad, A.; Simard, A.; Nassim, D.; Jfri, A.; Alajmi, A.; O’brien, E.; Wortsman, X. Performance of Ultrasound for Identifying Morphological Characteristics and Thickness of Cutaneous Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Dermatology 2022, 238, 692–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamas, T.; Dinu, C.; Lenghel, L.M.; Boțan, E.; Tamas, A.; Stoia, S.; Leucuta, D.C.; Bran, S.; Onisor, F.; Băciuț, G.; et al. High-Frequency Ultrasound in Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer in the Head and Neck Region. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Barcaui, E.; Carvalho, A.C.P.; Valiante, P.M.; Piñeiro-Maceira, J.; Barcaui, C.B. High-frequency (22-MHz) ultrasound for assessing the depth of basal cell carcinoma invasion. Skin. Res. Technol. 2021, 27, 676–681. [Google Scholar]

- Siskou, S.; Pasquali, P.; Trakatelli, M. High Frequency Ultrasound of Basal Cell Carcinomas: Ultrasonographic Features and Histological Subtypes, a Retrospective Study of 100 Tumors. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, R.; Al-Sabah, H. The Histomorphologic Profile of Skin Diseases in Kuwait. Cureus 2023, 15, e48729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, M.; Jones, D.B.; Maloney, M.E. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1990, 23, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wortsman, X. Ultrasound in Skin Cancer: Why, How, and When to Use It? Cancers 2024, 16, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortsman, X.; Vergara, P.; Castro, A.; Saavedra, D.; Bobadilla, F.; Sazunic, I.; Zemelman, V.; Wortsman, J. Ultrasound as predictor of histologic subtypes linked to recurrence in basal cell carcinoma of the skin. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 29, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculet, E.; Craescu, M.; Rebegea, L.; Bobeica, C.; Nastase, F.; Lupasteanu, G.; Stan, D.J.; Chioncel, V.; Anghel, L.; Lungu, M.; et al. Basal cell carcinoma: Comprehensive clinical and histopathological aspects, novel imaging tools and therapeutic approaches (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 23, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Boulinguez, S.; Grison-Tabone, C.; Lamant, L.; Valmary, S.; Viraben, R.; Bonnetblanc, J.; Bedane, C. Histological evolution of recurrent basal cell carcinoma and therapeutic implications for incompletely excised lesions. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 151, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyöngy, M.; Balogh, L.; Szalai, K.; Kalló, I. Histology-based simulations of ultrasound imaging: Methodology. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2013, 39, 1925–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csány, G.; Szalai, K.; Gyöngy, M. A real-time data-based scan conversion method for single element ultrasound transducers. Ultrasonics 2019, 93, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lupu, M.; Caruntu, C.; Popa, M.I.; Voiculescu, V.M.; Zurac, S.; Boda, D. Vascular patterns in basal cell carcinoma: Dermoscopic, confocal and histopathological perspectives. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 4112–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raszewska-Famielec, M.; Borzęcki, A.; Krasowska, D.; Chodorowska, G. Clinical usefulness of high-frequency ultrasonography in the monitoring of basal cell carcinoma treatment effects. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2020, 37, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartore, L.; Lancerotto, L.; Salmaso, M.; Giatsidis, G.; Paccagnella, O.; Alaibac, M.; Bassetto, F. Facial basal cell carcinoma: Analysis of recurrence and follow-up strategies. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 26, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeets, N.W.; Krekels, G.A.; Ostertag, J.U.; Essers, B.A.; Dirksen, C.D.; Nieman, F.H.; Neumann, H.M. Surgical excision vs. Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: Randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004, 364, 1766–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mc Loone, N.M.; Tolland, J.; Walsh, M.; Dolan, O.M. Follow-up of basal cell carcinomas: An audit of current practice. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2006, 20, 698–701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crisan, D.; Tarnowietzki, E.; Bernhard, L.; Möller, M.; Scharffetter-Kochanek, K.; Crisan, M.; Schneider, L.A. Rationale for Using High-Frequency Ultrasound as a Routine Examination in Skin Cancer Surgery: A Practical Approach. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortsman, X. Ultrasound in dermatology: Why, how, and when? Semin. Ultrasound CT MR 2013, 34, 177–195. [Google Scholar]

- Daviti, M.; Lallas, K.; Dimitriadis, C.; Moutsoudis, A.; Eleftheriadis, V.; Eftychidou, P.; Bakirtzi, M.; Stefanou, E.; Gkentsidi, T.; Papadimitriou, I.; et al. Real-Life Data on the Management of Incompletely Excised Basal Cell Carcinoma. Dermatology 2023, 239, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Solid Lesions | Infiltrative Lesions | Statistical Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contour | Mostly well-defined margins | Mostly irregular/ill-defined margins | OR = 71.9, 95% CI: 37.0–139.8 χ2 = 24.7, df = 1, p < 0.001 |

| Vascularity | More commonly hypervascular | Strongly predisposed to hypovascularity | OR = 6.06, 95% CI: 3.51–10.46 χ2 = 23.8, df = 1, p < 0.001 |

| Vascularity | Infiltrative (n) | Solid (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypervascular | 80 | 67 |

| Hypovascular | 145 | 38 |

| Age Group (Years) | Most Frequently Observed Ultrasound Features 1 |

|---|---|

| 20–29 | Infiltrative and superficial morphology |

| 30–39 | Solid, nodular, and adenomatous morphology |

| 40–49 | Increased frequency of hypervascular lesions |

| 50–59 | Mixed vascularity patterns |

| 60–69 | Increased frequency of irregular contours |

| ≥70 | Combined presence of irregular contour and hypervascularity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Szalai, K.; Tóth, K.; Hársing, J.; Gyöngy, M.; Holló, P. High-Frequency Ultrasound Assessment of Basal Cell Carcinoma: Correlations Between Histopathological Subtype, Vascularity, and Age/Sex Distribution. Cancers 2026, 18, 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020274

Szalai K, Tóth K, Hársing J, Gyöngy M, Holló P. High-Frequency Ultrasound Assessment of Basal Cell Carcinoma: Correlations Between Histopathological Subtype, Vascularity, and Age/Sex Distribution. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020274

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzalai, Klára, Klaudia Tóth, Judit Hársing, Miklós Gyöngy, and Péter Holló. 2026. "High-Frequency Ultrasound Assessment of Basal Cell Carcinoma: Correlations Between Histopathological Subtype, Vascularity, and Age/Sex Distribution" Cancers 18, no. 2: 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020274

APA StyleSzalai, K., Tóth, K., Hársing, J., Gyöngy, M., & Holló, P. (2026). High-Frequency Ultrasound Assessment of Basal Cell Carcinoma: Correlations Between Histopathological Subtype, Vascularity, and Age/Sex Distribution. Cancers, 18(2), 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020274