Outcomes Following Radiotherapy for Oligoprogressive NSCLC on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Real-World, Multinational Experience

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Outcomes and Statistical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haslam, A.; Prasad, V. Estimation of the percentage of US patients with cancer who are eligible for and respond to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy drugs. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e192535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, A.J.; Hellmann, M.D. Acquired Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, D.A.; Olson, R.; Harrow, S.; Gaede, S.; Louie, A.V.; Haasbeek, C.; Mulroy, L.; Lock, M.; Rodrigues, G.B.; Yaremko, B.P.; et al. Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy for the Comprehensive Treatment of Oligometastatic Cancers: Long-Term Results of the SABR-COMET Phase II Randomized Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2830–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, D.A.; Olson, R.; Harrow, S.; Gaede, S.; Louie, A.V.; Haasbeek, C.; Mulroy, L.; Lock, M.; Rodrigues, G.B.; Yaremko, B.P.; et al. Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy versus Standard of Care Palliative Treatment in Patients with Oligometastatic Cancers (SABR-COMET): A Randomised, Phase 2, Open-Label Trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 2051–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, P.; Wardak, Z.; Gerber, D.E.; Tumati, V.; Ahn, C.; Hughes, R.S.; Dowell, J.E.; Cheedella, N.; Nedzi, L.; Westover, K.D.; et al. Consolidative Radiotherapy for Limited Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, e173501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, D.R.; Tang, C.; Zhang, J.; Blumenschein, G.R., Jr.; Hernandez, M.; Lee, J.J.; Ye, R.; Palma, D.A.; Louie, A.V.; Camidge, D.R.; et al. Local Consolidative Therapy Vs. Maintenance Therapy or Observation for Patients with Oligometastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Long-Term Results of a Multi-Institutional, Phase II, Randomized Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1558–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiontov, S.I.; Pitroda, S.P.; Weichselbaum, R.R. Oligometastasis: Past, Present, Future. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 108, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.H.; Palma, D.; McDonald, F.; Tree, A.C. The Dandelion Dilemma Revisited for Oligoprogression: Treat the Whole Lawn or Weed Selectively? Clin. Oncol. 2019, 31, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Yazdanpanah, O.; Harris, J.P.; Nagasaka, M. Consolidative Radiotherapy in Oligometastatic and Oligoprogressive NSCLC: A Systematic Review. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2025, 210, 104676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Y.; Salem, J.-E.; Cohen, J.V.; Chandra, S.; Menzer, C.; Ye, F.; Zhao, S.; Das, S.; Beckermann, K.E.; Ha, L.; et al. Fatal Toxic Effects Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Updated Analysis of KEYNOTE-024: Pembrolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score of 50% or Greater. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; Spigel, D.R.; Steins, M.; Ready, N.E.; Chow, L.Q.; Vokes, E.E.; Felip, E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, U.; Josephides, E.; Chitnis, M.; Skwarski, M.; Gennatas, S.; Ghosh, S.; Spicer, J.; Karapanagiotou, E.; Ahmad, T.; Forster, M.; et al. Predictors and Outcomes of Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Patients Following Severe Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Toxicity: A Real-World UK Multi-Centre Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, B.M.; Schoenfeld, J.D.; Trippa, L. Hazards of Hazard Ratios—Deviations from Model Assumptions in Immunotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1158–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, U.; Huynh, M.A.; Killoran, J.H.; Qian, J.M.; Bent, E.H.; Aizer, A.A.; Mak, R.H.; Mamon, H.J.; Balboni, T.A.; Gunasti, L.; et al. Retrospective Review of Outcomes After Radiation Therapy for Oligoprogressive Disease on Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2022, 114, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, Y.; Guckenberger, M.; Gomez, D.; Hoyer, M.; Iyengar, P.; Kindts, I.; Méndez Romero, A.; Nevens, D.; Palma, D.; Park, C.; et al. Defining Oligometastatic Disease from a Radiation Oncology Perspective: An ESTRO-ASTRO Consensus Document. Radiother. Oncol. 2020, 148, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemen, N.D.; Wang, M.; Feingold, P.L.; Cooper, K.; Pavri, S.N.; Han, D.; Detterbeck, F.C.; Boffa, D.J.; Khan, S.A.; Olino, K.; et al. Patterns of Failure after Immunotherapy with Checkpoint Inhibitors Predict Durable Progression-Free Survival after Local Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.J.; Yang, J.T.; Shaverdian, N.; Patel, J.; Shepherd, A.F.; Eng, J.; Guttmann, D.; Yeh, R.; Gelblum, D.Y.; Namakydoust, A.; et al. Consolidative Use of Radiotherapy to Block (CURB) Oligoprogression—Randomised Study of Standard-of-Care Systemic Therapy with or without Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Patients with Oligoprogressive Cancers of the Breast and Lung. Lancet 2024, 403, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauml, J.M.; Mick, R.; Ciunci, C.; Aggarwal, C.; Davis, C.; Evans, T.; Deshpande, C.; Miller, L.; Patel, P.; Alley, E.; et al. Pembrolizumab After Completion of Locally Ablative Therapy for Oligometastatic Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase 2 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metro, G.; Addeo, A.; Signorelli, D.; Gili, A.; Economopoulou, P.; Roila, F.; Banna, G.; De Toma, A.; Rey Cobo, J.; Camerini, A.; et al. Outcomes from Salvage Chemotherapy or Pembrolizumab beyond Progression with or without Local Ablative Therapies for Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers with PD-L1 ≥50% Who Progress on First-Line Immunotherapy: Real-World Data from a European Cohort. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, 4972–4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettinger, S.N.; Wurtz, A.; Goldberg, S.B.; Rimm, D.; Schalper, K.; Kaech, S.; Kavathas, P.; Chiang, A.; Lilenbaum, R.; Zelterman, D.; et al. Clinical Features and Management of Acquired Resistance to PD-1 Axis Inhibitors in 26 Patients with Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018, 13, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, P.; All, S.; Berry, M.F.; Boike, T.P.; Bradfield, L.; Dingemans, A.-M.C.; Feldman, J.; Gomez, D.R.; Hesketh, P.J.; Jabbour, S.K.; et al. Treatment of Oligometastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: An ASTRO/ESTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 13, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanni, T.B.; Grills, I.S.; Kestin, L.L.; Robertson, J.M. Stereotactic Radiotherapy Reduces Treatment Cost While Improving Overall Survival and Local Control over Standard Fractionated Radiation Therapy for Medically Inoperable Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 34, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toi, Y.; Sugawara, S.; Kawashima, Y.; Aiba, T.; Kawana, S.; Saito, R.; Tsurumi, K.; Suzuki, K.; Shimizu, H.; Sugisaka, J.; et al. Association of Immune-Related Adverse Events with Clinical Benefit in Patients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Nivolumab. Oncologist 2018, 23, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postow, M.A.; Sidlow, R.; Hellmann, M.D. Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Su, Y.; Jiao, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B. T Cells in Health and Disease. Sig Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Park, S.; Han, K.-Y.; Lee, N.; Kim, H.; Jung, H.A.; Sun, J.-M.; Ahn, J.S.; Ahn, M.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; et al. Clonal Expansion of Resident Memory T Cells in Peripheral Blood of Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer during Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e005509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, H.; Zhu, K.; Wang, R. Predictive Effect of PD-L1 Expression for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor (PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors) Treatment for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 80, 106214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, U. Radiotherapy Driven Immunomodulation of the Tumor Microenvironment and Its Impact on Clinical Outcomes: A Promising New Treatment Paradigm. Immunol. Med. 2022, 45, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, O.; Guijosa, A.; Heredia, D.; Dávila-Dupont, D.; Rios-Garcia, E. P3.06D.05 Stratifying Risk in Oligoprogressive EGFR-Mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The Role of ctDNA. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, S323–S324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Number of Patients (N = 103) | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Age at OPD diagnosis (years) | ||

| Median | 68 | |

| Range | 44–90 | |

| Interquartile range | 62–74 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 46 | 45% |

| Female | 57 | 55% |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Never Smoker | 15 | 15% |

| Current Smoker | 20 | 19% |

| Former Smoker | 64 | 62% |

| Unknown | 4 | 4% |

| PD-L1 TPS Status * | ||

| <1% | 18 | 18% |

| 1–49% | 18 | 18% |

| ≥50% | 41 | 40% |

| Total Number of Patients (N = 103 *) | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Anatomic location of radiated OPD lesions | ||

| Lung | 33 | 32% |

| Brain | 26 | 25% |

| Lymph node | 10 | 10% |

| Spine | 10 | 10% |

| Bone | 8 | 8% |

| Other sites ** | 16 | 16% |

| Duration of treatment with last ICI before OPD diagnosis (months) | ||

| Median | 5.55 | |

| Interquartile range | 2.07–10.56 | |

| Best overall response to last ICI | ||

| Complete Response | 4 | 4% |

| Partial Response | 41 | 40% |

| Mixed response | 2 | 2% |

| Stable Disease | 32 | 31% |

| Progressive Disease | 15 | 15% |

| Unevaluable | 9 | 9% |

| Response of OPD lesions to prior ICI | ||

| Patients with new lesions | 45 | 44% |

| Patients with lesions previously responsive or stable on ICI | 43 | 42% |

| Patients with lesions that never responded to ICI | 14 | 14% |

| Patients with new lesions and lesions that never responded to ICI | 1 | 1% |

| Number of OPD lesions | ||

| Patients with 1 OPD lesion | 79 | 77% |

| Patients with 2 OPD lesions | 18 | 17% |

| Patients with >2 OPD lesions | 6 | 6% |

| Radiation modality used to treat OPD lesions | ||

| SABR/SRS/SRT | 49 | 48% |

| Non-stereotactic RT | 50 | 49% |

| Other radiation modality † | 4 | 4% |

| Radiation total dose by EQD2 levels | ||

| Low EQD2 (≤40 Gy) | 42 | 41% |

| Intermediate EQD2 (>40 Gy and <80 Gy) | 40 | 39% |

| High EQD2 (≥80 Gy) | 15 | 15% |

| Low and intermediate EQD2 | 6 | 6% |

| Re-irradiation of OPD lesions | ||

| Yes | 6 | 6% |

| No | 97 | 94% |

| LC | PFS | OS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) * | p-Value | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) * | p-Value | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) * | p-Value | |

| Age at OPD diagnosis | 1.00 (0.94–1.04) | 0.77 | N/A | N/A | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.17 | N/A | N/A | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 0.50 | N/A | N/A |

| Gender (Male vs. Female) | 1.36 (0.52–3.53) | 0.53 | N/A | N/A | 1.50 (0.91–2.47) | 0.11 | N/A | N/A | 1.85 (1.04–3.28) | 0.04 | N/A | N/A |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||||

| Current Smoker | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Former Smoker | 0.79 (0.25–2.51) | 0.68 | N/A | N/A | 1.13 (0.60–2.16) | 0.70 | N/A | N/A | 0.90 (0.45–1.80) | 0.76 | N/A | N/A |

| Never Smoker | 1.05 (0.24– 4.72) | 0.95 | N/A | N/A | 1.39 (0.60–3.23) | 0.44 | N/A | N/A | 1.14 (0.45–2.87) | 0.78 | N/A | N/A |

| PD-L1 TPS status(≥50% vs. <50%) | 2.67 (0.71–10.09) | 0.15 | N/A | N/A | 0.98 (0.53–1.79) | 0.94 | N/A | N/A | 1.19 (0.57–2.50) | 0.64 | N/A | N/A |

| KRAS (Mutant vs. wild type) | 0.42 (0.12–1.53) | 0.19 | N/A | N/A | 0.52 (0.30–0.92) | 0.02 | 0.62 (0.35–1.11) | 0.11 | 0.73 (0.39–1.37) | 0.33 | N/A | N/A |

| Anatomic location of OPD lesions (Visceral vs. non-visceral) | 0.64 (0.24–1.66) | 0.35 | N/A | N/A | 0.56 (0.32–0.99) | 0.046 | 0.45 (0.24–0.83) | 0.01 | 0.73 (0.39–1.37) | 0.32 | N/A | N/A |

| Number of OPD lesions | 1.06 (0.60–1.86) | 0.84 | N/A | N/A | 1.11 (0.82–1.47) | 0.54 | N/A | N/A | 0.95 (0.68–1.33) | 0.77 | N/A | N/A |

| Median cumulative OPD lesion volume (≤11.57 cm3 vs. >11.57 cm3) | 1.05 (0.55–1.98) | 0.89 | N/A | N/A | 1.09 (0.33–3.58) | 0.89 | N/A | N/A | 0.52 (0.25–1.08) | 0.08 | N/A | N/A |

| LC | PFS | OS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) * | p-Value | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) * | p-Value | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) * | p-Value | |

| Radiation modality (SABR/SRS vs. Conventional RT) | 0.94 (0.42–2.07) | 0.87 | N/A | N/A | 0.83 (0.50–1.37) | 0.47 | N/A | N/A | 0.57 (0.32–1.03) | 0.06 | N/A | N/A |

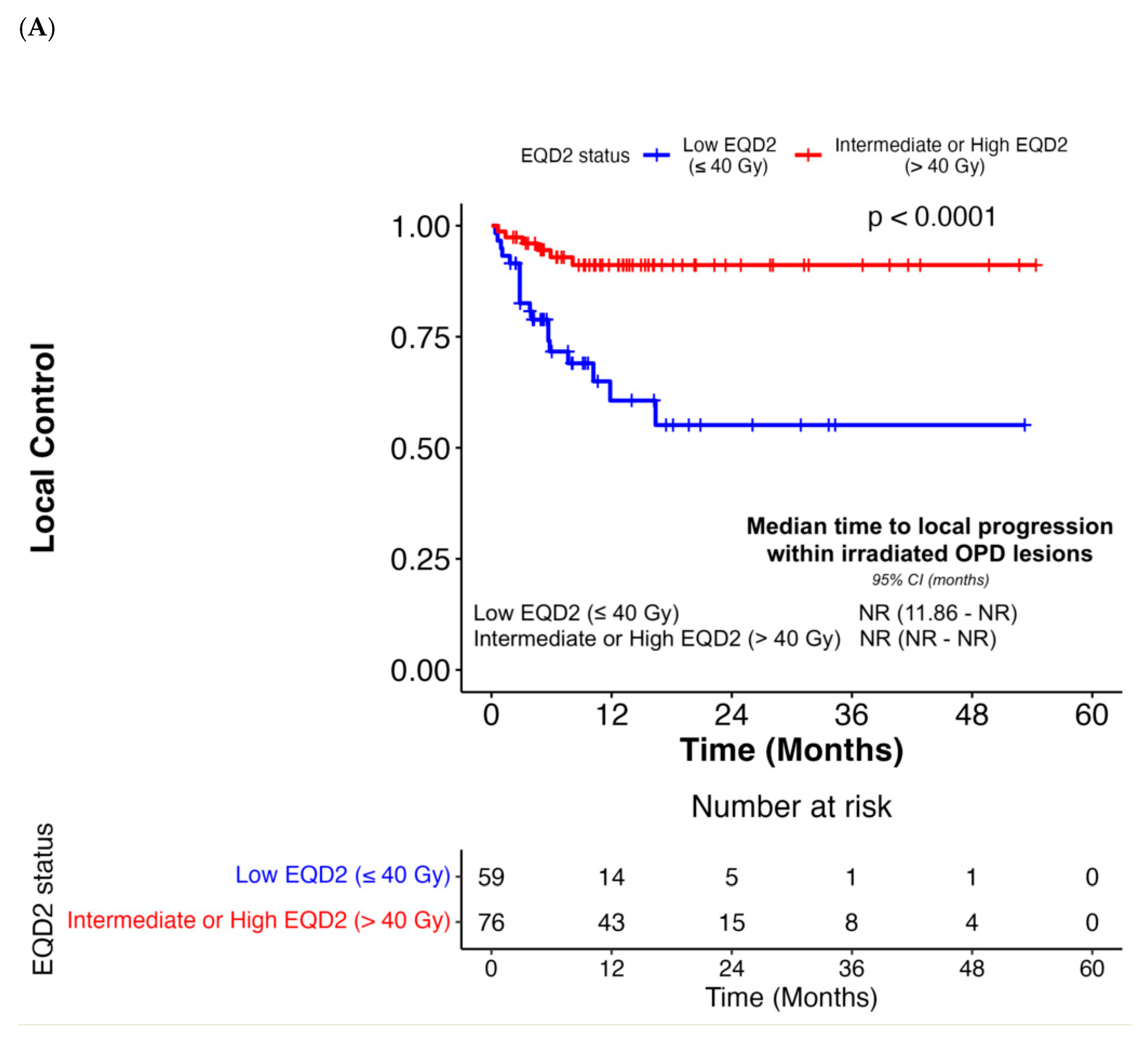

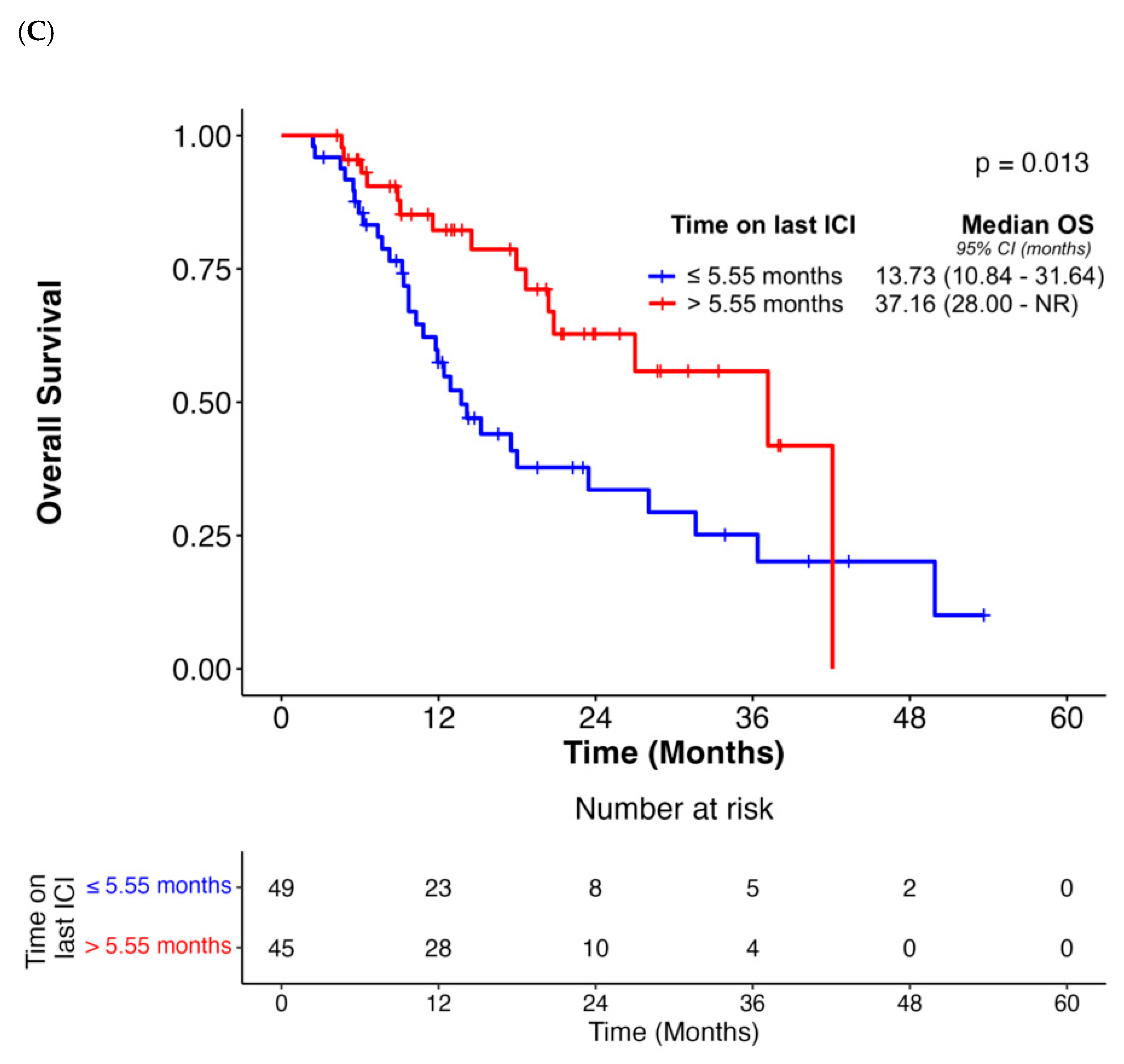

| EQD2 status (α/β = 10) | ||||||||||||

| Low EQD2 (≤40 Gy) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Intermediate or High EQD2 (>40 Gy) | 0.19 (0.07–0.47) | < 0.001 | 0.14 (0.04–0.56) | 0.005 | 0.69 (0.41–1.16) | 0.16 | N/A | N/A | 0.44 (0.24–0.79) | 0.007 | 0.35 (0.16–0.80) | 0.01 |

| Local treatment response to RT in OPD lesions (Responders vs. Non-Responders) | 0.21 (0.08–0.53) | < 0.001 | 0.07 (0.01–0.48) | 0.007 | 0.55 (0.32–0.96) | 0.04 | 0.65 (0.37–1.17) | 0.15 | 0.47 (0.24–0.91) | 0.03 | 0.38 (0.19–0.76) | 0.006 |

| Response of OPD lesions to prior ICI | ||||||||||||

| Previously responsive or stable on ICI | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Never responded to ICI | 1.01 (0.28–3.62) | 0.99 | N/A | N/A | 1.10 (0.52–2.32) | 0.81 | N/A | N/A | 1.54 (0.72–3.29) | 0.27 | N/A | N/A |

| New lesions | 0.76 (0.33–1.76) | 0.53 | N/A | N/A | 0.84 (0.48–1.45) | 0.52 | N/A | N/A | 0.83 (0.44–1.57) | 0.58 | N/A | N/A |

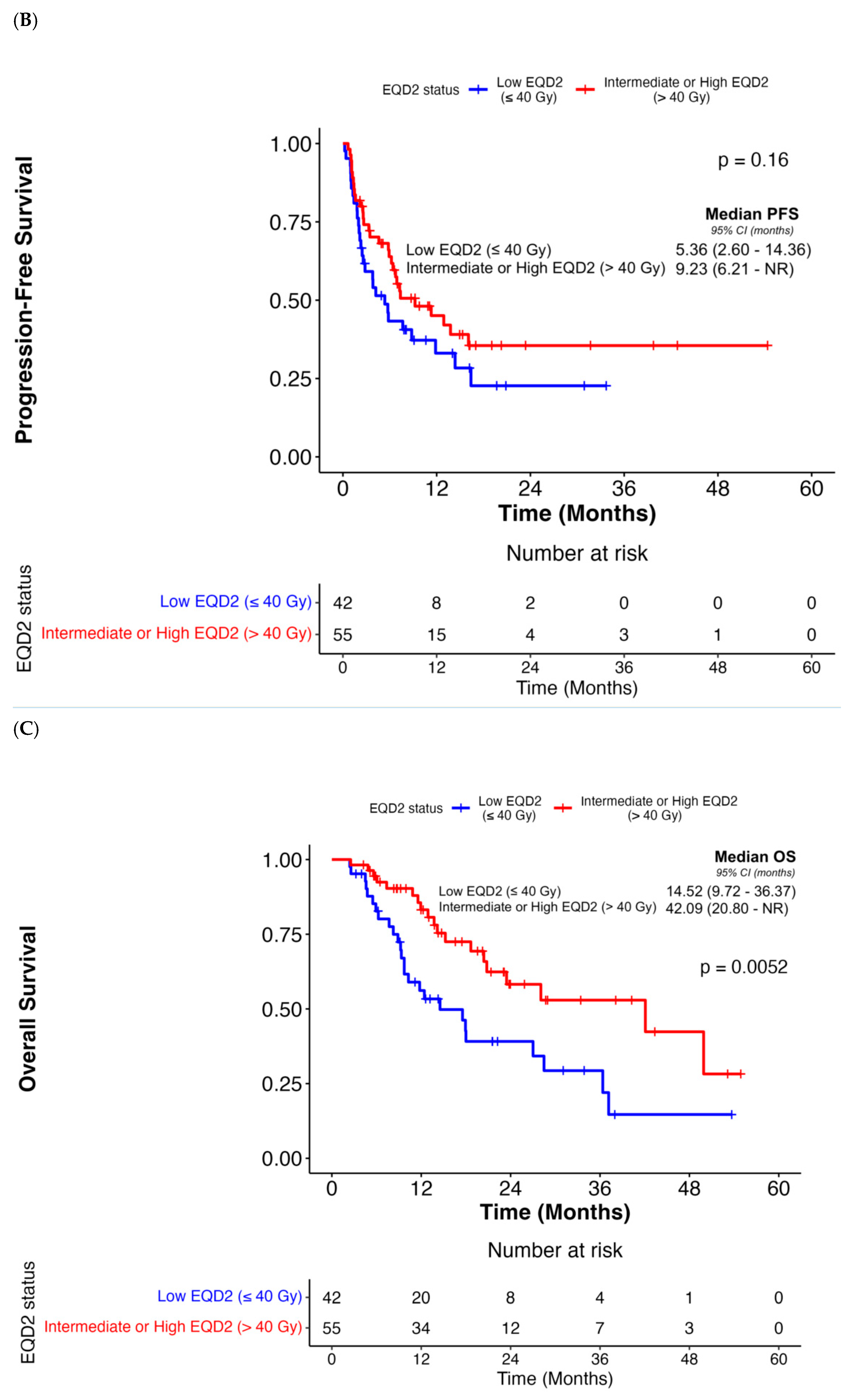

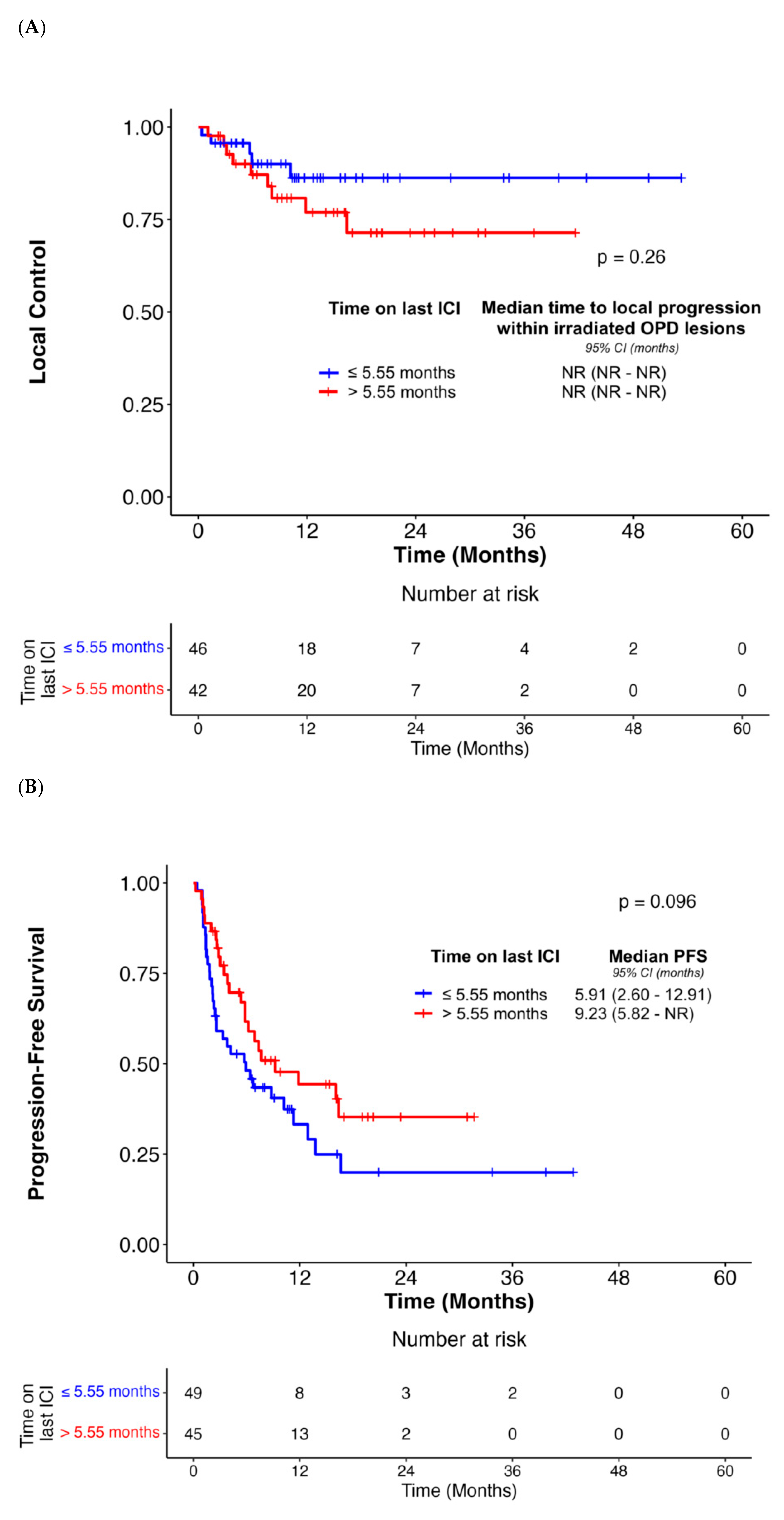

| Median duration of last ICI before OPD diagnosis (>5.55 months vs. ≤5.55 months) | 1.86 (0.62–5.56) | 0.27 | N/A | N/A | 0.64 (0.38–1.09) | 0.10 | N/A | N/A | 0.46 (0.25–0.87) | 0.02 | 0.47 (0.24–0.93) | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mahmood, U.; Josephides, E.; Coupe, N.; Smith, D.; Ahmad, S.; Al-Salihi, O.; Mak, S.M.; Chitnis, M.; Georgiou, A.; Ajzensztejn, D.; et al. Outcomes Following Radiotherapy for Oligoprogressive NSCLC on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Real-World, Multinational Experience. Cancers 2026, 18, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010071

Mahmood U, Josephides E, Coupe N, Smith D, Ahmad S, Al-Salihi O, Mak SM, Chitnis M, Georgiou A, Ajzensztejn D, et al. Outcomes Following Radiotherapy for Oligoprogressive NSCLC on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Real-World, Multinational Experience. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010071

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahmood, Umair, Eleni Josephides, Nicholas Coupe, Daniel Smith, Shahreen Ahmad, Omar Al-Salihi, Sze M. Mak, Meenali Chitnis, Alexandros Georgiou, Daniel Ajzensztejn, and et al. 2026. "Outcomes Following Radiotherapy for Oligoprogressive NSCLC on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Real-World, Multinational Experience" Cancers 18, no. 1: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010071

APA StyleMahmood, U., Josephides, E., Coupe, N., Smith, D., Ahmad, S., Al-Salihi, O., Mak, S. M., Chitnis, M., Georgiou, A., Ajzensztejn, D., Karapanagiotou, E., Higgins, G. S., Panakis, N., Schoenfeld, J. D., & Skwarski, M. (2026). Outcomes Following Radiotherapy for Oligoprogressive NSCLC on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Real-World, Multinational Experience. Cancers, 18(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010071