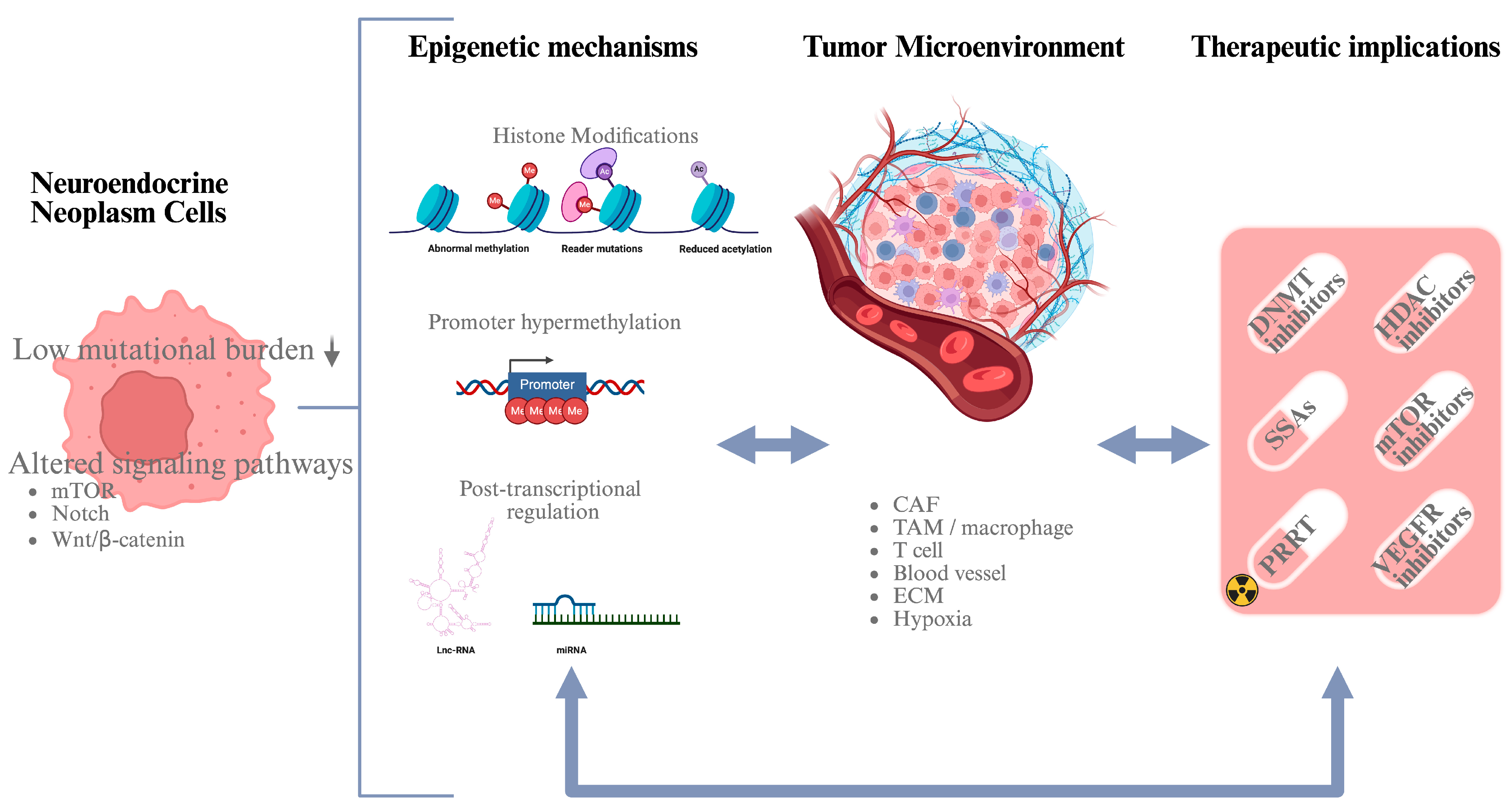

Epigenetics and the Tumor Microenvironment in Neuroendocrine Tumors

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Neuroendocrine Neoplasms

2. Epigenetics of NETs

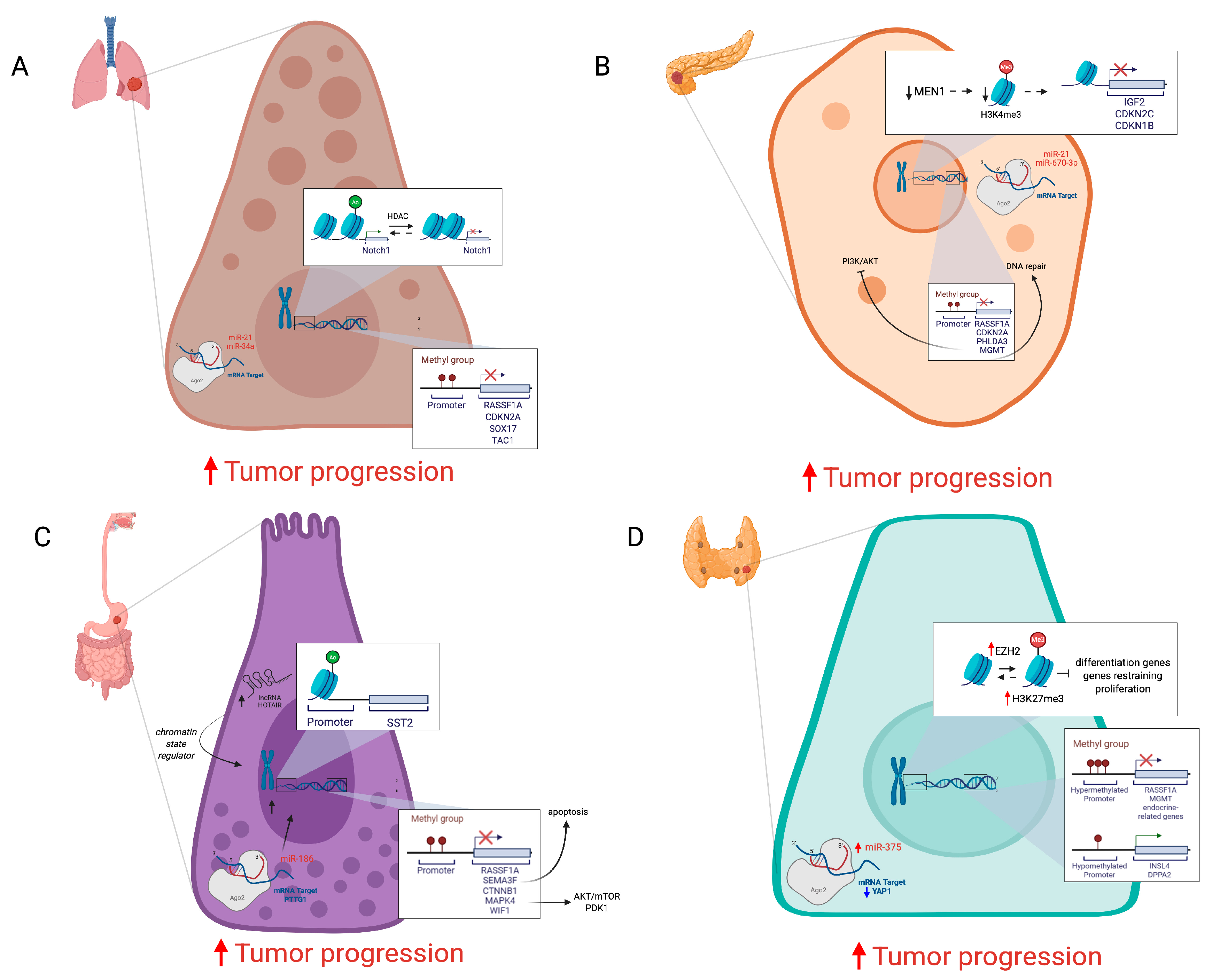

2.1. DNA Methylation

2.2. Histone Modifications

2.3. Noncoding RNAs

2.4. Emerging Epigenetic Mechanisms

3. Tumor Microenvironments in NETs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NEN | Neuroendocrine Neoplasm |

| NET | Neuroendocrine Tumor |

| NEC | Neuroendocrine Carcinoma |

| GEP | Gastroenteropancreatic |

| MEN1 | Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 |

| NF1 | Neurofibromatosis Type 1 |

| TSC1/2 | Tuberous Sclerosis |

| VHL | Von Hippel–Lindau |

| TC | Typical Carcinoid |

| AC | Atypical Carcinoid |

| LCNEC | Large-Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma |

| SCLC | Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma |

| PanNEC | Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Carcinoma |

| PanNET | Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor |

| SSA | Somatostatin Analog |

| HDACi | Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor |

| DNMTi | DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitor |

| MTC | Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| TIL | Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte |

| CAF | Cancer-Associated Fibroblast |

| TAM | Tumor-Associated Macrophage |

| MDSC | Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell |

| DC | Dendritic Cell |

| LIF | Leukemia Inducible Factor |

References

- Rizen, E.N.; Phan, A.T. Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Relevant Clinical Update. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 24, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahba, A.; Tan, Z.; Dillon, J.S. Management of Functional Neuroendocrine Tumors. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2024, 52, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.S.; Ziv, E. Neuroendocrine Tumors: Genomics and Molecular Biomarkers with a Focus on Metastatic Disease. Cancers 2023, 15, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauricella, E.; Chaoul, N.; D’Angelo, G.; Giglio, A.; Cafiero, C.; Porta, C.; Palmirotta, R. Neuroendocrine Tumors: Germline Genetics and Hereditary Syndromes. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2025, 26, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendifar, A.E.; Marchevsky, A.M.; Tuli, R. Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Lung: Current Challenges and Advances in the Diagnosis and Management of Well-Differentiated Disease. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 12, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vocino Trucco, G.; Righi, L.; Volante, M.; Papotti, M. Updates on Lung Neuroendocrine Neoplasm Classification. Histopathology 2024, 84, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colapietra, F.; Della Monica, P.; Di Napoli, R.; França Vieira e Silva, F.; Settembre, G.; Marino, M.M.; Ballini, A.; Cantore, S.; Di Domenico, M. Epigenetic Modifications as Novel Biomarkers for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Targeting in Thyroid, Pancreas, and Lung Neuroendocrine Tumors. JCM 2025, 14, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. IRDR 2017, 6, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, L.; Prasad, S.R.; Sunnapwar, A.; Kondapaneni, S.; Dasyam, A.; Tammisetti, V.S.; Salman, U.; Nazarullah, A.; Katabathina, V.S. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: 2020 Update on Pathologic and Imaging Findings and Classification. RadioGraphics 2020, 40, 1240–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stawarski, A.; Maleika, P. Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Gastrointestinal Tract and Pancreas: Is It Also a Challenge for Pediatricians? Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 29, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Barbieri, A.; Gibson, J. Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Gastrointestinal Tract and Pancreas. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2019, 12, 1021–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farsetti, A.; Illi, B.; Gaetano, C. How Epigenetics Impacts on Human Diseases. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 114, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colao, A.; De Nigris, F.; Modica, R.; Napoli, C. Clinical Epigenetics of Neuroendocrine Tumors: The Road Ahead. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 604341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, A.; Wiedmer, T.; Marinoni, I.; Perren, A. Genetic and Epigenetic Drivers of Neuroendocrine Tumours (NET). Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2017, 24, R315–R334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, R.; Song, L.; Li, H.; Wang, Z. Differentiation of Duodenal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors from Hypervascular Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors in the Pancreatic Head Using Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography. Abdom. Radiol. 2019, 44, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffoli, L.; Ditsiou, A.; Gagliano, T. Exploring Emerging Therapeutic Targets and Opportunities in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Updates on Receptor Tyrosine Kinases. Receptors 2024, 3, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliano, T.; Brancolini, C. Epigenetic Mechanisms beyond Tumour–Stroma Crosstalk. Cancers 2021, 13, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, K.; Chen, E.Y.; Kardosh, A.; Lopez, C.D.; Del Rivero, J.; Mallak, N.; Rocha, F.G.; Koethe, Y.; Pommier, R.; Mittra, E.; et al. Therapy Resistant Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancers 2022, 14, 4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, S.; Renzi, S.; Giovinazzo, F.; Bermano, G. mTOR Pathway in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (GEP-NETs). Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 562505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozas, J.; San Román, M.; Alonso-Gordoa, T.; Pozas, M.; Caracuel, L.; Carrato, A.; Molina-Cerrillo, J. Targeting Angiogenesis in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Resistance Mechanisms. IJMS 2019, 20, 4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhang, L.; Yin, C.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Sun, L.; Sun, J. Characterization of Zinc Finger Protein 536, a Neuroendocrine Regulator, Using Pan-Cancer Analysis. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, J.; Jiang, J.; Guan, H.; Zhu, R.; Li, N.; Liu, W.; Wang, C. Determination and Characterization of Molecular Heterogeneity and Precision Medicine Strategies of Patients with Pancreatic Cancer and Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Based on Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction-Related Genes. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1127441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Huang, D.; Qin, Y.; Lou, X.; Gao, H.; Ye, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Jing, D.; et al. Small Extracellular Vesicle-miR-183-5p Mediated Crosstalk between Tumor Cells and Macrophages in High-Risk Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Oncogene 2025, 44, 2907–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, L.D.; Le, T.; Fan, G. DNA Methylation and Its Basic Function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, A.; Nakanishi, M. Navigating the DNA Methylation Landscape of Cancer. Trends Genet. 2021, 37, 1012–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavasi, E.; Adamo, M.; Zamprogno, E.; Vella, V.; Giamas, G.; Gagliano, T. Decoding the Tumour Microenvironment: Molecular Players, Pathways, and Therapeutic Targets in Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2024, 16, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geissler, F.; Nesic, K.; Kondrashova, O.; Dobrovic, A.; Swisher, E.M.; Scott, C.L.; Wakefield, M.J. The Role of Aberrant DNA Methylation in Cancer Initiation and Clinical Impacts. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2024, 16, 17588359231220511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, W.D.; Flanders, T.Y.; Pollock, P.M.; Hayward, N.K. The CDKN2A (P16) Gene and Human Cancer. Mol. Med. 1997, 3, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raos, D.; Ulamec, M.; Katusic Bojanac, A.; Bulic-Jakus, F.; Jezek, D.; Sincic, N. Epigenetically Inactivated RASSF1A as a Tumor Biomarker. Bosn. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 2020, 21, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, L.; McKenna, S.; Kolch, W.; Matallanas, D. RASSF1A Tumour Suppressor: Target the Network for Effective Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Jia, Y.; Yu, Y.; Brock, M.V.; Herman, J.G.; Han, C.; Su, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M. SOX17 Methylation Inhibits Its Antagonism of Wnt Signaling Pathway in Lung Cancer. Discov. Med. 2014, 14, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Helyes, Z.; Elekes, K.; Sándor, K.; Szitter, I.; Kereskai, L.; Pintér, E.; Kemény, Á.; Szolcsányi, J.; McLaughlin, L.; Vasiliou, S.; et al. Involvement of Preprotachykinin A Gene-Encoded Peptides and the Neurokinin 1 Receptor in Endotoxin-Induced Murine Airway Inflammation. Neuropeptides 2010, 44, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Tan, L.; Xiao, X.; Xin, B.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ke, Z.; Yin, J. Detection of the DNA Methylation of Seven Genes Contribute to the Early Diagnosis of Lung Cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, J.S. Epigenetic Regulation in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 901435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, W.A.; Krishnaraj, J.; Ohki, R. The Role of PHLDA3 in Cancer Progression and Its Potential as a Therapeutic Target. Cancers 2025, 17, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S.; Beaumont, J.; Braga, M.; Masrour, N.; Mauri, F.; Beckley, A.; Butt, S.; Karali, C.S.; Cawthorne, C.; Archibald, S.; et al. Epigenetic Potentiation of Somatostatin-2 by Guadecitabine in Neuroendocrine Neoplasias as a Novel Method to Allow Delivery of Peptide Receptor Radiotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 176, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirosh, A.; Kebebew, E. Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2020, 11, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cives, M.; Simone, V.; Rizzo, F.M.; Silvestris, F. NETs: Organ-Related Epigenetic Derangements and Potential Clinical Applications. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 57414–57429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanoli, M.; La Rosa, S.; Sahnane, N.; Romualdi, C.; Pastorino, R.; Marando, A.; Capella, C.; Sessa, F.; Furlan, D. Prognostic Relevance of Aberrant DNA Methylation in G1 and G2 Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2014, 100, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinoni, I.; Wiederkeher, A.; Wiedmer, T.; Pantasis, S.; Di Domenico, A.; Frank, R.; Vassella, E.; Schmitt, A.; Perren, A. Hypo-Methylation Mediates Chromosomal Instability in Pancreatic NET. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2017, 24, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsom, K.G.; Van Veenendaal, L.M.; Valk, G.D.; Vriens, M.R.; Tesselaar, M.E.T.; Van Den Berg, J.G. Molecular Prognostic Factors in Small-Intestinal Neuroendocrine Tumours. Endocr. Connect. 2019, 8, 906–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdugo, A.D.; Crona, J.; Starker, L.; Stålberg, P.; Åkerström, G.; Westin, G.; Hellman, P.; Björklund, P. Global DNA Methylation Patterns through an Array-Based Approach in Small Intestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2014, 21, L5–L7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Dai, T.; Guo, M.; Zhao, X.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, M.; Xu, L.; Zhao, J. A Review of Non-Classical MAPK Family Member, MAPK4: A Pivotal Player in Cancer Development and Therapeutic Intervention. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotouhi, O.; Adel Fahmideh, M.; Kjellman, M.; Sulaiman, L.; Höög, A.; Zedenius, J.; Hashemi, J.; Larsson, C. Global Hypomethylation and Promoter Methylation in Small Intestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors: An In Vivo and In Vitro Study. Epigenetics 2014, 9, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y.; Yasuda, N.; Bundo, M.; Nakachi, Y.; Ueda, J.; Ishimoto, T.; Iwatsuki, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Yoshida, N.; Oshiumi, H.; et al. LINE -1 Hypomethylation, Increased Retrotransposition and Tumor-specific Insertion in Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer. Cancer Sci. 2024, 115, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Monica, R.; Cuomo, M.; Visconti, R.; Di Mauro, A.; Buonaiuto, M.; Costabile, D.; De Riso, G.; Di Risi, T.; Guadagno, E.; Tafuto, R.; et al. Evaluation of MGMT Gene Methylation in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Oncol. Res. 2021, 28, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodero, S.; Fernández, A.F.; Fernández-Morera, J.L.; Castro-Santos, P.; Bayon, G.F.; Ferrero, C.; Urdinguio, R.G.; Gonzalez-Marquez, R.; Suarez, C.; Fernández-Vega, I.; et al. DNA Methylation Signatures Identify Biologically Distinct Thyroid Cancer Subtypes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 2811–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Hu, X.; Wang, X. Crossing Epigenetic Frontiers: The Intersection of Novel Histone Modifications and Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R.L.; Weissbach, J.; Kleilein, J.; Bell, J.; Hüttelmaier, S.; Viol, F.; Clauditz, T.; Grabowski, P.; Laumen, H.; Rosendahl, J.; et al. Targeting HDACs in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Models. Cells 2021, 10, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W.A.; Takebayashi, S.; Abdalla, M.O.A.; Fujino, K.; Kudoh, S.; Motooka, Y.; Sato, Y.; Naito, Y.; Higaki, K.; Wakimoto, J.; et al. Correlation between Histone Acetylation and Expression of Notch1 in Human Lung Carcinoma and Its Possible Role in Combined Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma. Lab. Investig. 2017, 97, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbat, M.A.; Abdulhalim, Y.H.; Al Rabeai, M.; Abdou Hassan, W.A.M. Role of Notch1 Signaling Pathway in Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Iran. J. Pathol. 2024, 19, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ye, B.; Hong, L.; Xu, H.; Fishbein, M.C. Epigenetic Modifications of Histone H4 in Lung Neuroendocrine Tumors. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2011, 19, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-W.; Kim, K.-C.; Kim, K.-B.; Dunn, C.T.; Park, K.-S. Transcriptional Deregulation Underlying the Pathogenesis of Small Cell Lung Cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2018, 7, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, F.; Pan, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Chi, P.; You, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, A.; Zhao, L.; et al. KMT2C Deficiency Promotes Small Cell Lung Cancer Metastasis through DNMT3A-Mediated Epigenetic Reprogramming. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Jothi, R. Genome-Wide Characterization of Menin-Dependent H3K4me3 Reveals a Specific Role for Menin in the Regulation of Genes Implicated in MEN1-Like Tumors. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Watanabe, H.; Peng, S.; Francis, J.M.; Kaplan, N.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Ramachandran, A.; Agoston, A.; Bass, A.J.; Meyerson, M. Dynamic Epigenetic Regulation by Menin During Pancreatic Islet Tumor Formation. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015, 13, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magerl, C.; Ellinger, J.; Braunschweig, T.; Kremmer, E.; Koch, L.K.; Höller, T.; Büttner, R.; Lüscher, B.; Gütgemann, I. H3K4 Dimethylation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Is Rare Compared with Other Hepatobiliary and Gastrointestinal Carcinomas and Correlates with Expression of the Methylase Ash2 and the Demethylase LSD1. Hum. Pathol. 2010, 41, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomp, M.J.; Refardt, J.; Van Koetsveld, P.M.; Campana, C.; Dalm, S.U.; Dogan, F.; Van Velthuysen, M.-L.F.; Feelders, R.A.; De Herder, W.W.; Hofland, J.; et al. Epigenetic Regulation of SST2 Expression in Small Intestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1184436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sponziello, M.; Durante, C.; Boichard, A.; Dima, M.; Puppin, C.; Verrienti, A.; Tamburrano, G.; Di Rocco, G.; Redler, A.; Lacroix, L.; et al. Epigenetic-Related Gene Expression Profile in Medullary Thyroid Cancer Revealed the Overexpression of the Histone Methyltransferases EZH2 and SMYD3 in Aggressive Tumours. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014, 392, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenker, N.; Flanagan, J.M. Intragenic DNA Methylation: Implications of This Epigenetic Mechanism for Cancer Research. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Getz, G.; Miska, E.A.; Alvarez-Saavedra, E.; Lamb, J.; Peck, D.; Sweet-Cordero, A.; Ebert, B.L.; Mak, R.H.; Ferrando, A.A.; et al. MicroRNA Expression Profiles Classify Human Cancers. Nature 2005, 435, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X. The Roles of microRNAs in Epigenetic Regulation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 51, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen, B.M.; Hidayat, H.J.; Salihi, A.; Sabir, D.K.; Taheri, M.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. MicroRNA: A Signature for Cancer Progression. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.; Qianjiang, H.; Fu, R.; Yang, H.; Shi, A.; Luo, H. Epigenetic and Epitranscriptomic Role of lncRNA in Carcinogenesis (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2025, 66, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurry, H.S.; Rivero, J.D.; Chen, E.Y.; Kardosh, A.; Lopez, C.D.; Pegna, G.J. Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Epigenetic Landscape and Clinical Implications. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2024, 52, 101131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demes, M.; Aszyk, C.; Bartsch, H.; Schirren, J.; Fisseler-Eckhoff, A. Differential miRNA-Expression as an Adjunctive Diagnostic Tool in Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Lung. Cancers 2016, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, P.; Siddiqui, J.A.; Kshirsagar, P.G.; Venkata, R.C.; Maurya, S.K.; Mirzapoiazova, T.; Perumal, N.; Chaudhary, S.; Kanchan, R.K.; Fatima, M.; et al. MicroRNA-1 Attenuates the Growth and Metastasis of Small Cell Lung Cancer through CXCR4/FOXM1/RRM2 Axis. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, B.; Sheng, Z.; Sun, N.; Yuan, B.; Wu, X. Identification of lncRNA, miRNA and mRNA Expression Profiles and ceRNA Networks in Small Cell Lung Cancer. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyasovska, N.; Valkova, N.; Gala, M.; Bendikova, S.; Abdulhamed, A.; Palicka, V.; Renwick, N.; Čekan, P.; Paul, E. Deep Sequencing Reveals Distinct microRNA-mRNA Signatures That Differentiate Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor from Non-Diseased Pancreas Tissue. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipinikas, C.P.; Berner, A.M.; Sposito, T.; Thirlwell, C. The Evolving (Epi)Genetic Landscape of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2019, 26, R519–R544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, L.; Vitale, F.; Giansanti, G.; Esposto, G.; Borriello, R.; Mignini, I.; Nicoletti, A.; Zileri Dal Verme, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ainora, M.E.; et al. Decoding Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Molecular Profiles, Biomarkers, and Pathways to Personalized Therapy. IJMS 2025, 26, 7814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez-Encinas, R.; Moreno-Montilla, M.T.; García-Vioque, V.; Gracia-Navarro, F.; Alors-Pérez, E.; Pedraza-Arevalo, S.; Ibáñez-Costa, A.; Castaño, J.P. The Uprise of RNA Biology in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Altered Splicing and RNA Species Unveil Translational Opportunities. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2023, 24, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Tang, L.; Ding, R.; Shi, L.; Liu, A.; Chen, D.; Shao, C. Long Noncoding RNA-mRNA Expression Profiles and Validation in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Clin. Endocrinol. 2020, 92, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewska, A.; Kidd, M.; Matar, S.; Kos-Kudla, B.; Modlin, I.M. A Comprehensive Assessment of the Role of miRNAs as Biomarkers in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2018, 107, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, N.; Knief, J.; Kacprowski, T.; Lazar-Karsten, P.; Keck, T.; Billmann, F.; Schmid, S.; Luley, K.; Lehnert, H.; Brabant, G.; et al. MicroRNA Analysis of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Metastases. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 28379–28390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Mauro, A.; Scognamiglio, G.; Aquino, G.; Cerrone, M.; Liguori, G.; Clemente, O.; Di Bonito, M.; Cantile, M.; Botti, G.; Tafuto, S.; et al. Aberrant Expression of Long Non Coding RNA HOTAIR and De-Regulation of the Paralogous 13 HOX Genes Are Strongly Associated with Aggressive Behavior of Gastro-Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. IJMS 2021, 22, 7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.; Duncavage, E.; Tamburrino, A.; Salerno, P.; Xi, L.; Raffeld, M.; Moley, J.; Chernock, R.D. Overexpression of miR-10a and miR-375 and Downregulation of YAP1 in Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2013, 95, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, M.; Daneii, P.; Zandieh, M.A.; Raesi, R.; Zahmatkesh, N.; Bayat, M.; Abuelrub, A.; Khazaei Koohpar, Z.; Aref, A.R.; Zarrabi, A.; et al. Non-Coding RNA-Mediated N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) Deposition: A Pivotal Regulator of Cancer, Impacting Key Signaling Pathways in Carcinogenesis and Therapy Response. Non-Coding RNA Res. 2024, 9, 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Bao, X.; Li, D.; Ye, Z.; Xiang, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, L.; Xue, C.; et al. FTO-Mediated DSP m6A Demethylation Promotes an Aggressive Subtype of Growth Hormone-Secreting Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, K.; Ochiai, M.; Kojima, K.; Kato, K.; Ando, T.; Kato, T.; Ito, H. The SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complex Subunit BAF53B as an Immunohistochemical Marker for Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Hum. Cell 2025, 38, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The Evolving Tumor Microenvironment: From Cancer Initiation to Metastatic Outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cives, M.; Pelle’, E.; Quaresmini, D.; Rizzo, F.M.; Tucci, M.; Silvestris, F. The Tumor Microenvironment in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Biology and Therapeutic Implications. Neuroendocrinology 2019, 109, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centonze, G.; Maisonneuve, P.; Mathian, É.; Grillo, F.; Sabella, G.; Lagano, V.; Mangogna, A.; Pusceddu, S.; Bossi, P.; Spaggiari, P.; et al. Digital Immunophenotyping of Lung Atypical Carcinoids and Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinomas Identifies Three Subtypes with Specific Tumor-Immune Microenvironment Features. Endocr. Pathol. 2025, 36, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.; Xu, L.; Lu, F.; Chen, L.; Hu, C.; Chen, J.; Xue, B.; Gu, D.; Xu, R.; Xu, Y.; et al. Hypoxia Drives CBR4 Down-regulation Promotes Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors via Activation Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Mediated by Fatty Acid Synthase. J. Cell Commun. Signal 2024, 18, e12041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.; Kundu, A.; Kundu, C.N. The Cytokines in Tumor Microenvironment: From Cancer Initiation-Elongation-Progression to Metastatic Outgrowth. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2024, 196, 104311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.E.; Park, S.H.; Jang, Y.K. Epigenetic Up-Regulation of Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) Gene During the Progression to Breast Cancer. Mol. Cells 2011, 31, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, A.; Xu, J.; Meng, J.; Tang, L.; Lyu, S. Epigenetics: Mechanisms, Potential Roles, and Therapeutic Strategies in Cancer Progression. Genes. Dis. 2024, 11, 101020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, T.-S.; Chan, L.K.-Y.; Wong, E.C.-H.; Hui, C.W.-C.; Sneddon, K.; Cheung, T.-H.; Yim, S.-F.; Lee, J.H.-S.; Yeung, C.S.-Y.; Chung, T.K.-H.; et al. A Loop of Cancer-Stroma-Cancer Interaction Promotes Peritoneal Metastasis of Ovarian Cancer via TNFα-TGFα-EGFR. Oncogene 2017, 36, 3576–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-C.; Chen, C.-W.; Yang, C.-L.; Tsai, I.-M.; Hou, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-J.; Shan, Y.-S. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Promote Epigenetic Silencing of Gelsolin through DNA Methyltransferase 1 in Gastric Cancer Cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhu, X. Exosomal Non-Coding RNAs-Mediated Crosstalk in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 646864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tumor Site | Origin Cells | Classification | Mutated Genes/Hereditary Syndromes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lungs | Pulmonary neuroendocrine cells (neuroepithelial bodies) |

| MEN1, SWI/SNF complex, KMT2/MLL, and PSIP1 [6] |

| Pancreas | Islet cells of the pancreas |

| MEN1, VHL, NF-1, tuberous sclerosis complex, and glucagon cell adenomatosis [8,9] |

| GI tract | Enterochromaffin cells of the gut neuroendocrine system |

| MEN1, VHL syndrome, NF1, and tuberous sclerosis [11] |

| Thyroid | Mainly C-cells of the thyroid gland |

| MEN2 syndromes and RET [7] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Castenetto, A.; Gagliano, T. Epigenetics and the Tumor Microenvironment in Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancers 2026, 18, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010069

Castenetto A, Gagliano T. Epigenetics and the Tumor Microenvironment in Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastenetto, Alice, and Teresa Gagliano. 2026. "Epigenetics and the Tumor Microenvironment in Neuroendocrine Tumors" Cancers 18, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010069

APA StyleCastenetto, A., & Gagliano, T. (2026). Epigenetics and the Tumor Microenvironment in Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancers, 18(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010069