Freeze the Disease: Advances the Therapy for Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

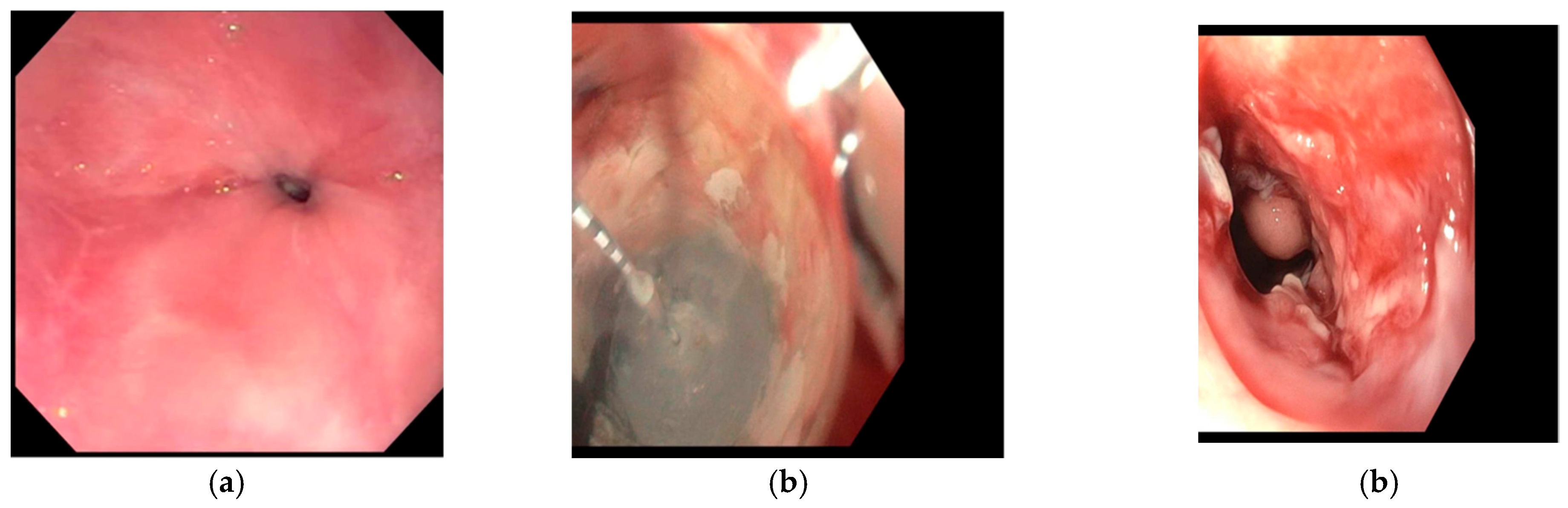

2. Evolution of Cryotherapy

3. Mechanism of Injury

4. Types of Endoscopic Cryotherapy Methods

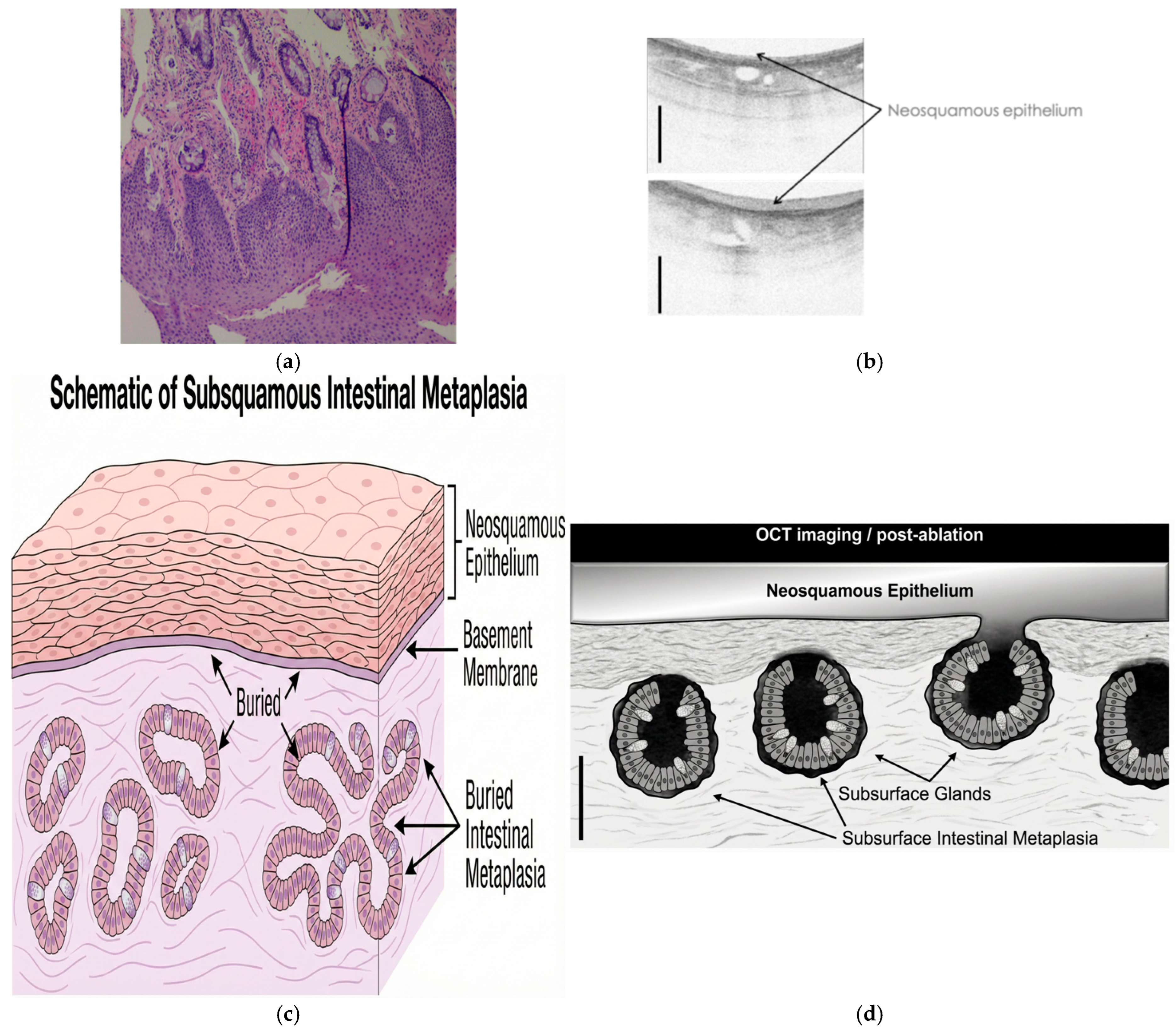

5. Depth of Injury and Buried Glands

6. Safety and Efficacy of Cryotherapy

| Studies | Type of Study | Patients Included | Efficacy | Safety & Recurrence | Median Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gosain et al. [26] | Observational | 32 BE-HGD | 32/32 CE-HGD 27/32 CE-IM | AE: 3 strictures | 2 years |

| Canto et al. [29] | Retrospective Single center | 20 treatment naïve 44 rescue treatment | Year 1: 10/13 CE-EAC 60/64 CE-D 35/64 CE-IM Long-term CE for neoplasia: 56/64 | AE: 2 serious events 4 post cryotherapy pain Recurrence: 20/64 IM | 4 years |

| Ghorbani et al. [33] | Prospective Multicenter | 23 LGD 57 HGD | LGD: 91% CE-D 61% CE-IM HGD: 81% CE-D 65% CE-IM Short segment BE: 97% CE-D, 77% CE-IM | AE: 1 stricture 1 GI bleed | 2 years |

| Ramay et al. [34] | 50 BE-HGD or EAC | Year 3: 48/50 CE-HGD 47/50 CE-D 41/50 CE-IM Year 5: 37/40 CE-HGD 35/40 CE-D 30/40 CE-IM | AE: None Recurrence: 12.2% IM 4% Dysplasia 1.4% HGD/EAC | 5 years | |

| Kaul et al. [31] | Retrospective Single center | 57 long-segment BE | 39/52 CE-IM 51/52 CE-D | AE: 1 GI bleed 1 esophageal micro perforation Recurrence: 3/39 IM 4/39 Dysplasia 2/39 HGD | 4.8 years |

| Dbouk et al. [32] | Prospective Single center | 59 BE with LGD, HGD, or EAC | Year 1: 53/56 CE-D 42/56 CE-IM Year 3: 45/45 CE-D 40/41 CE-IM | AE: 5 stricture 1 GI bleed Recurrence: 14.6% IM 1.4% Dysplasia | 4.5 years |

| Eluri et al. [35] | Prospective Multicenter | 138 BE with LGD, HGD, and EAC | Year 2: 66% CE-IM 84% CE-D Year 3: 67% CE-IM 92% CE-D | AE: 5.5% stricture 0.7% perforation Recurrence: 8.8% IM | 2.5 years |

7. Comparison of Cryotherapy and Radiofrequency Ablation

| Studies | Type of Study | No. Patients Included/Type of Therapy | Efficacy | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Munster et al. [44] | Prospective 2-centers | 20 Balloon cryotherapy 26 RFA | BE regression: Cryo = 88% RFA = 90% p = 0.62 | Peak pain: cryo/RFA = 2/4 days Pain duration: cryo/RFA = 2/4 days Analgesic usage: cryo/RFA = 2/4 days All P < 0.01 |

| Thota et al. [36] | Retrospective Single Center Heterogenous | 81 cryotherapy 73 RFA | CE-IM: Cryo/RFA = 41%/67% CE-LGD Cryo/RFA = 79%/88% CE-HGD: Cryo/RFA = 88%/88% Progression: Cryo/RFA = 13%/13% Comparble response between RFA/LNSCT | Not reported |

| Canto et al. [29] | Prospective clinical trial | 22 treatment naïve 19 previous RFA Treatment: Co2—Cryotherapy | CE-IM: 88% CE-D: 95% CE-HGD 95% CE-EAC 80% | 4 strictures 1 GI bleed (aspirin) |

| Fasullo et al. [38] | Retrospective Multicenter | 62 cryotherapy (LNSCT) 100 RFA | CE-D: LNSCT vs. RFA = 71% vs. 81%, p = 0.14 CE-IM: LNSCT vs. RFA = 66% vs. 64%, p = 0.78 | No significant adverse event reported |

| Sachdeva et al. [40] | Retrospective 2-centers | 71 cryoballoon 610 RFA Compared: Propensity matched 54 patients | Comparable Dysplastic recurrence rate Between CBA/RFA Baseline Barrett’s segment length independent risk factor for Dysplastic recurrence and all recurrence. | No significant adverse event reported |

8. Cryotherapy as a Salvage Therapy in Refractory Barrett’s Esophagus

9. Cryotherapy in the Palliative Management of Malignancy

10. Cryo-Immunology

11. Conclusions/Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Then, E.O.; Lopez, M.; Saleem, S.; Gayam, V.; Sunkara, T.; Culliford, A.; Gaduputi, V. Esophageal Cancer: An Updated Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Database Analysis. World J. Oncol. 2020, 11, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Xue, L.; Wang, L. Current status and perspectives of esophageal cancer: A comprehensive review. Cancer Commun. 2024, 45, 281–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Gastroenterological Association; Spechler, S.J.; Sharma, P.; Souza, R.F.; Inadomi, J.M.; Shaheen, N.J. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, N.J.; Sharma, P.; Overholt, B.F.; Wolfsen, H.C.; Sampliner, R.E.; Wang, K.K.; Galanko, J.A.; Bronner, M.P.; Goldblum, J.R.; Bennett, A.E.; et al. Radiofrequency Ablation in Barrett’s Esophagus with Dysplasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 2277–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.; Bejarano, P.; Livingstone, A.; Sparling, L.; Franceschi, D.; Ardalan, B. Depth of Injury Caused by Liquid Nitrogen Cryospray: Study of Human Patients Undergoing Planned Esophagectomy. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2014, 59, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Meng, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Progress in the cryoablation and cryoimmunotherapy for tumor. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1094009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, T.; Kushnir, V.; Mutha, P.; Majhail, M.; Patel, B.; Schutzer, M.; Mogahanaki, D.; Smallfield, G.; Patel, M.; Zfass, A. Neoadjuvant cryotherapy improves dysphagia and may impact remission rates in advanced esophageal cancer. Endosc. Int. Open 2019, 07, E1522–E1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Yu, Z.; Tang, X.; Chen, W.; Deng, X.; Zhu, X. Cryoablation combined with dual immune checkpoint blockade enhances antitumor efficacy in hepatocellular carcinoma model mice. Int. J. Hyperth. 2024, 41, 2373319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alteber, Z.; Azulay, M.; Cafri, G.; Vadai, E.; Tzehoval, E.; Eisenbach, L. Cryoimmunotherapy with local co-administration of ex vivo generated dendritic cells and CpG-ODN immune adjuvant, elicits a specific antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014, 63, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, A.A. History of cryosurgery. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 1998, 14, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Farhangian, M.; Snyder, A.; E Huang, K.; Doerfler, L.; Huang, W.W.; Feldman, S.R. Cutaneous cryosurgery in the United States. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2016, 27, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Risk, M.C.; Goldfarb, R.; Reddy, B.; Coles, B.; Dahm, P. Primary cryotherapy for localised or locally advanced prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD005010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baust, J.G.; Gage, A.A. The molecular basis of cryosurgery. BJU Int. 2005, 95, 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, A.A.; Baust, J. Mechanisms of tissue injury in cryosurgery. Cryobiology 1998, 37, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Addona, T.; Nair, D.G.; Qi, L.; Ravikumar, T.S. Apoptosis induced by cryo-injury in human colorectal cancer cells is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 103, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, A.A.; Baust, J.M.; Baust, J.G. Experimental cryosurgery investigations in vivo. Cryobiology 2009, 59, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, N.E.; Bischof, J.C. The cryobiology of cryosurgical injury. Urology 2002, 60, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwald, B.D.; Dumot, J.A.; Abrams, J.A.; Lightdale, C.J.; David, D.S.; Nishioka, N.S.; Yachimski, P.; Johnston, M.H.; Shaheen, N.J.; Zfass, A.M.; et al. Endoscopic spray cryotherapy for esophageal cancer: Safety and efficacy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010, 71, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, L.S.; Nierkens, S.; Weusten, B.L. Applications of cryotherapy in premalignant and malignant esophageal disease: Preventing, treating, palliating disease and enhancing immunogenicity? World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2025, 17, 103746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, S.; Triadafilopoulos, G. A novel device for ablation of abnormal esophageal mucosa (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011, 74, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashimo, H. Subsquamous intestinal metaplasia after ablation of Barrett’s esophagus: Frequency and importance. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 29, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, M.J.; Hwang, J.H.; Upton, M.P.; Chen, Y.; Oelschlager, B.K.; Wood, D.E.; Kimmey, M.B.; Li, X. Imaging of subsquamous Barrett’s epithelium with ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography: A histologic correlation study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010, 71, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Krulisky, K.; Millard, T.; Sullivan, C.; Molina, C.; Clay, D.; Srivastav, S.K.; Joshi, V. Factors Affecting Response to Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) in Barrett’s Esophagus: Does Depth of Disease Matter? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, S179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spechler, S.J. Buried (but not dead) Barrett’s metaplasia: Tales from the crypts. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2012, 76, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackroyd, R.; Brown, N.J.; Stephenson, T.J.; Stoddard, C.J.; Reed, M.W. Ablation treatment for Barrett oesophagus: What depth of tissue destruction is needed? J. Clin. Pathol. 1999, 52, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosain, S.; Mercer, K.; Twaddell, W.S.; Uradomo, L.; Greenwald, B.D. Liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy in Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia: Long-term results. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2013, 78, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genere, J.R.; Visrodia, K.; Zakko, L.; Hoefnagel, S.J.M.; Wang, K.K. Spray cryotherapy versus continued radiofrequency ablation in persistent Barrett’s esophagus. Dis. Esophagus 2022, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandan, S.; Bapaye, J.; Khan, S.R.; Deliwala, S.S.; Mohan, B.P.; Ramai, D.; Dhindsa, B.S.; Goyal, H.; Kassab, L.L.; Aziz, M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy in Barrett’s neoplasia—a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Endosc. Int. Open 2022, 10, E1462–E1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canto, M.I.; Shin, E.J.; Khashab, M.A.; Molena, D.; Okolo, P.; Montgomery, E.; Pasricha, P. Safety and efficacy of carbon dioxide cryotherapy for treatment of neoplastic Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy 2015, 47, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Munster, S.N.; Bergman, J.; Pouw, R.E. Systematic review for cryoablation of Barrett’s esophagus: Can we draw conclusions by combining apples, oranges and a banana? Endosc. Int. Open 2020, 8, E465–E466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, V.; Bittner, K.; Ullah, A.; Kothari, S. Liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy-based multimodal endoscopic management of dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus and early esophageal neoplasia: Retrospective review and long-term follow-up at an academic tertiary care referral center. Dis. Esophagus 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dbouk, M.; Simons, M.; Wang, B.; Rosenblum, M.; Gutierrez, O.I.B.; Shin, E.J.; Ngamruengphong, S.; Voltaggio, L.; Montgomery, E.; Canto, M.I. Durability of Cryoballoon Ablation in Neoplastic Barrett’s Esophagus. Tech. Innov. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2022, 24, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, S.; Tsai, F.C.; Greenwald, B.D. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic spray cryotherapy for Barrett’s dysplasia: Results of the National Cryospray Registry. Dis. Esophagus 2016, 29, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramay, F.H.; Cui, Q.; Greenwald, B.D. Outcomes after liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy in Barrett’s esophagus-associated high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal adenocarcinoma: 5-year follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017, 86, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eluri, S.; Cotton, C.C.; Kaul, V.; McKinley, M.; Pleskow, D.; Nishioka, N.; Hoffman, B.; Nieto, J.; Tsai, F.; Coyle, W.; et al. Liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy for eradication of dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus: Results from a multicenter prospective registry. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 100, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thota, P.N.; Arora, Z.; Dumot, J.A.; Falk, G.; Benjamin, T.; Goldblum, J.; Jang, S.; Lopez, R.; Vargo, J.J. Cryotherapy and Radiofrequency Ablation for Eradication of Barrett’s Esophagus with Dysplasia or Intramucosal Cancer. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, B.P.; Krishnamoorthi, R.; Ponnada, S.; Shakhatreh, M.; Jayaraj, M.; Garg, R.; Law, J.; Larsen, M.; Irani, S.; Ross, A.; et al. Liquid Nitrogen Spray Cryotherapy in Treatment of Barrett’s Esophagus: Where Do We Stand? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dis. Esophagus 2019, 32, doy130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasullo, M.; Shah, T.; Patel, M.; Mutha, P.; Zfass, A.; Lippman, R.; Smallfield, G. Outcomes of Radiofrequency Ablation Compared to Liquid Nitrogen Spray Cryotherapy for the Eradication of Dysplasia in Barrett’s Esophagus. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 67, 2320–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaefthymiou, A.; Norton, B.; Telese, A.; Ramai, D.; Murino, A.; Gkolfakis, P.; Vargo, J.; Haidry, R.J. Efficacy and Safety of Cryoablation in Barrett’s Esophagus and Comparison with Radiofrequency Ablation: A Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2024, 16, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdeva, K.; Chandi, P.S.; Verma, A.; Dierkhising, R.; Codipilly, D.C.; Leggett, C.L.; Trindade, A.J.; Iyer, P.G. Recurrence rates of Barrett’s esophagus and dysplasia in patients successfully treated with radiofrequency ablation vs. cryoballoon ablation: A comparative study. Endoscopy 2025, 57, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canto, M.I.; Shaheen, N.J.; Almario, J.A.; Voltaggio, L.; Montgomery, E.; Lightdale, C.J. Multifocal nitrous oxide cryoballoon ablation with or without EMR for treatment of neoplastic Barrett’s esophagus (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 88, 438–446.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamade, N.; Desai, M.; Chandrasekar, V.T.; Chalhoub, J.; Patel, M.; Duvvuri, A.; Gorrepati, V.S.; Jegadeesan, R.; Choudhary, A.; Sathyamurthy, A.; et al. Efficacy of cryotherapy as first line therapy in patients with Barrett’s neoplasia: A systematic review and pooled analysis. Dis. Esophagus 2019, 32, doz040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, R.; Enslin, S.; Hayat, M.; Kaul, V. Efficacy of Cryotherapy as a Primary Endoscopic Ablation Modality for Dysplastic Barrett’s Esophagus and Early Esophageal Neoplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancer Control. 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Munster, S.N.; Overwater, A.; Haidry, R.; Bisschops, R.; Bergman, J.J.; Weusten, B.L. Focal cryoballoon versus radiofrequency ablation of dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus: Impact on treatment response and postprocedural pain. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 88, 795–803.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, T.; Ansari, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Coyle, W.; Greenwald, B.B.; Kachaamy, T.; Kothari, S.; Sharma, N.; Smallfield, G.; Thakkar, S.; et al. Spray Cryotherapy Esophageal Consortium Consensus Recommendations for Liquid Nitrogen Spray Cryotherapy in Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Cancer Using a Modified Delphi Process. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halsey, K.D.; Chang, J.W.; Waldt, A.; Greenwald, B.D. Recurrent disease following endoscopic ablation of Barrett’s high-grade dysplasia with spray cryotherapy. Endoscopy 2011, 43, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, N.; Ketwaroo, G.A.; Bak, D.M.; Kedar, V.; Chuttani, R.; Berzin, T.M.; Sawhney, M.S.; Pleskow, D.K. Salvage cryotherapy after failed radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s esophagus–related dysplasia is safe and effective. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 82, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, A.J.; Inamdar, S.; Kothari, S.; Berkowitz, J.; McKinley, M.; Kaul, V. Feasibility of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy after failed radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s esophagus. Dig. Endosc. 2017, 29, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visrodia, K.; Zakko, L.; Singh, S.; Leggett, C.L.; Iyer, P.G.; Wang, K.K. Cryotherapy for persistent Barrett’s esophagus after radiofrequency ablation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 87, 1396–1404.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiceland, C.M.; Elmunzer, B.J.; Paros, S.; Roof, L.; McVey, M.; Hawes, R.; Hoffman, B.J.; Elias, P.S. Salvage cryotherapy in patients undergoing endoscopic eradication therapy for complicated Barrett’s esophagus. Endosc. Int. Open 2019, 07, E904–E911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.; Lee, J.H.; Thompson, C.C.; Faulx, A. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Optimal Management of the Malignant Alimentary Tract Obstruction: Expert Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1780–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakheet, N.; Park, J.-H.; Hu, H.-T.; Yoon, S.H.; Kim, K.Y.; Zhe, W.; Jeon, J.Y.; Song, H.-Y. Fully covered self-expandable esophageal metallic stents in patients with inoperable malignant disease who survived for more than 6 months after stent placement. Br. J. Radiol. 2019, 92, 20190321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachaamy, T.; Sharma, N.; Shah, T.; Mohapatra, S.; Pollard, K.; Zelt, C.; Jewett, E.; Garcia, R.; Munsey, R.; Gupta, S.; et al. A prospective multicenter study to evaluate the impact of cryotherapy on dysphagia and quality of life in patients with inoperable esophageal cancer. Endoscopy 2023, 55, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamantis, G.; Scarpa, M.; Bocus, P.; Realdon, S.; Castoro, C.; Ancona, E.; Battaglia, G. Quality of life in patients with esophageal stenting for the palliation of malignant dysphagia. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachaamy, T.; Prakash, R.; Kundranda, M.; Batish, R.; Weber, J.; Hendrickson, S.; Yoder, L.; Do, H.; Magat, T.; Nayar, R.; et al. Liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy for dysphagia palliation in patients with inoperable esophageal cancer. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 88, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiao, T.G.; Patel, S.A.; Sunkara, N.; Joshi, V. Freeze the Disease: Advances the Therapy for Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2026, 18, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010059

Xiao TG, Patel SA, Sunkara N, Joshi V. Freeze the Disease: Advances the Therapy for Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Ted G., Shree Atul Patel, Nishita Sunkara, and Virendra Joshi. 2026. "Freeze the Disease: Advances the Therapy for Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma" Cancers 18, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010059

APA StyleXiao, T. G., Patel, S. A., Sunkara, N., & Joshi, V. (2026). Freeze the Disease: Advances the Therapy for Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers, 18(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010059