Assessment of Local and Metastatic Recurrence Following Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy by Margin Status Using PSMA PET/CT Scan

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patient Cohorts

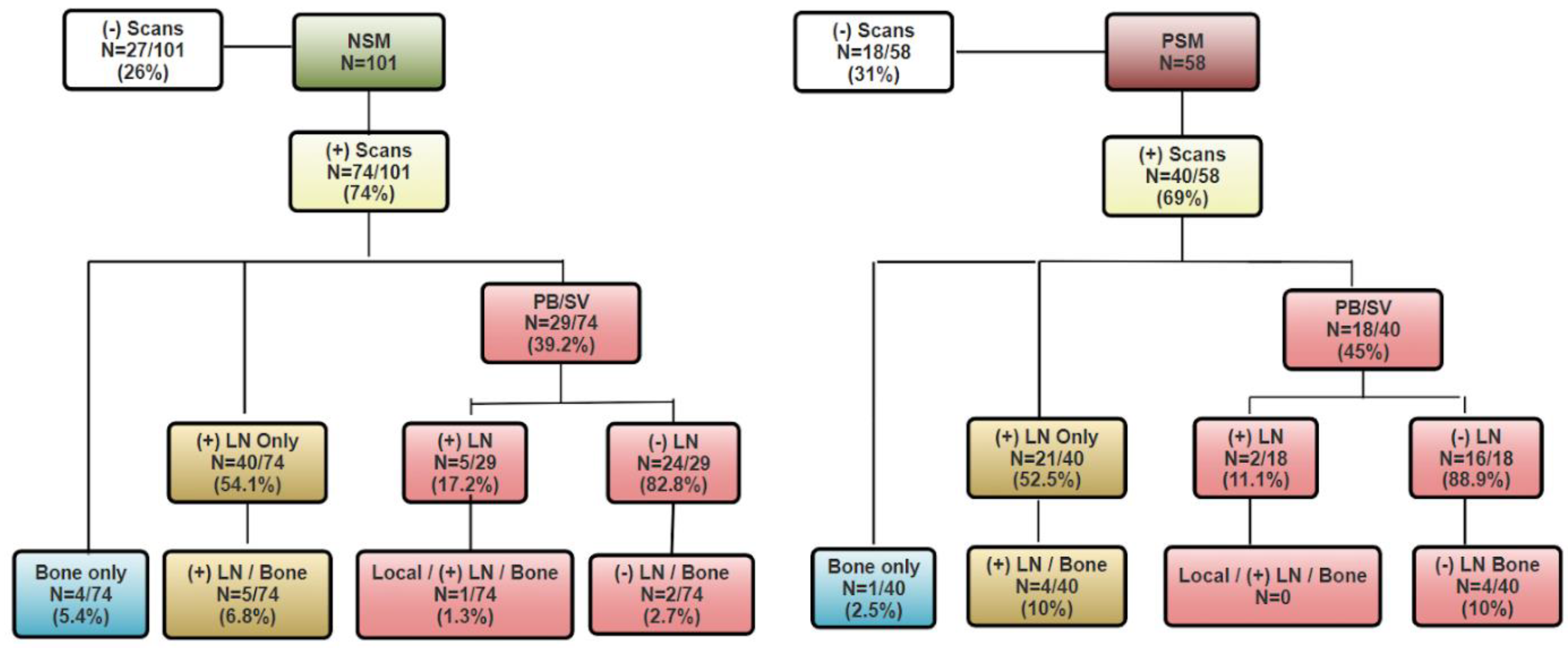

3.2. PSMA PET Findings by Margin Status

3.3. Pathological Stage Subgroup Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Prostate Cancer|Prostate Cancer Facts. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- American Cancer Society. Prostate. Available online: https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org/types/prostate (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Ahlering, T.; Huynh, L.M.; Kaler, K.S.; Williams, S.; Osann, K.; Joseph, J.; Lee, D.; Davis, J.W.; Abaza, R.; Kaouk, J.; et al. Unintended Consequences of Decreased PSA-Based Prostate Cancer Screening. World J. Urol. 2019, 37, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.H.; Raman, J.D. Impact of the Evolving United States Preventative Services Task Force Policy Statements on Incidence and Distribution of Prostate Cancer over 15 Years in a Statewide Cancer Registry. Prostate Int. 2021, 9, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.C.; Nguyen, P.; Mao, J.; Halpern, J.; Shoag, J.; Wright, J.D.; Sedrakyan, A. Increase in Prostate Cancer Distant Metastases at Diagnosis in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 705–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plambeck, B.D.; Wang, L.L.; Mcgirr, S.; Jiang, J.; Van Leeuwen, B.J.; Lagrange, C.A.; Boyle, S.L. Effects of the 2012 and 2018 US Preventive Services Task Force Prostate Cancer Screening Guidelines on Pathologic Outcomes after Prostatectomy. Prostate 2022, 82, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, L.; Aldrighetti, C.M.; Ghosh, A.; Niemierko, A.; Chino, F.; Huynh, M.J.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Kamran, S.C. Association of the USPSTF Grade D Recommendation Against Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening with Prostate Cancer-Specific Mortality. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2211869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, E.M.; Manola, J.; Yao, J.; Kiernan, M.; Crawford, D.; Wilding, G.; di’SantAgnese, P.A.; Trump, D. Immediate versus Deferred Androgen Deprivation Treatment in Patients with Node-Positive Prostate Cancer after Radical Prostatectomy and Pelvic Lymphadenectomy. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill-Axelson, A.; Holmberg, L.; Garmo, H.; Taari, K.; Busch, C.; Nordling, S.; Häggman, M.; Andersson, S.-O.; Andrén, O.; Steineck, G.; et al. Radical Prostatectomy or Watchful Waiting in Prostate Cancer—29-Year Follow-Up. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, M.; Lee, D.J.; Kent, M.; Xylinas, E.; Fritsche, H.-M.; Babjuk, M.; Brisuda, A.; Hansen, J.; Green, D.A.; Aziz, A.; et al. Predictors of Cancer-Specific Mortality after Disease Recurrence Following Radical Cystectomy. BJU Int. 2013, 111, E30–E36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboa-Barreiro, V.; Pértega-Díaz, S.; García-Rodríguez, T.; González-Martín, C.; Pardeiro-Pértega, R.; Yáñez-González-Dopeso, L.; Seoane-Pillado, T. Colorectal Cancer Recurrence and Its Impact on Survival after Curative Surgery: An Analysis Based on Multistate Models. Dig. Liver Dis. 2024, 56, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, R.; Valentini, A.; Hanna, W.; Rawlinson, E.; Rakovitch, E.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Factors Associated with Breast Cancer Mortality after Local Recurrence. Curr. Oncol. 2014, 21, e418–e425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Galloway, T.J.; Liu, J.C. The Impact of Positive Margin on Survival in Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2021, 122, 105499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, T.E.; Cruz, A.; Binitie, O.; Cheong, D.; Letson, G.D. Do Surgical Margins Affect Local Recurrence and Survival in Extremity, Nonmetastatic, High-Grade Osteosarcoma? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2016, 474, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, F.; Falagario, U.G.; Knipper, S.; Martini, A.; Akre, O.; Egevad, L.; Aly, M.; Moschovas, M.C.; Bravi, C.A.; Tran, J.; et al. Assessing the Impact of Positive Surgical Margins on Mortality in Patients Who Underwent Robotic Radical Prostatectomy: 20 Years’ Report from the EAU Robotic Urology Section Scientific Working Group. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2024, 7, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Liao, S.; Lu, G.; Geng, B.D.; Ye, Z.; Xu, J.; Ge, G.; Yang, D. Cellular Senescence in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Therapeutic Opportunity or Challenge (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.E.; Koch, M.O.; Jones, T.D.; Daggy, J.K.; Juliar, B.E.; Cheng, L. The Influence of Extent of Surgical Margin Positivity on Prostate Specific Antigen Recurrence. J. Clin. Pathol. 2005, 58, 1028–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzgreve, A.; Armstrong, W.R.; Clark, K.J.; Benz, M.R.; Smith, C.P.; Djaileb, L.; Gafita, A.; Thin, P.; Nickols, N.G.; Kishan, A.U.; et al. PSMA-PET/CT Findings in Patients with High-Risk Biochemically Recurrent Prostate Cancer with No Metastatic Disease by Conventional Imaging. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2452971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornford, P.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Brunckhorst, O.; Darraugh, J.; Eberli, D.; De Meerleer, G.; De Santis, M.; Farolfi, A.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer—2024 Update. Part I: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calais, J.; Fendler, W.P.; Eiber, M.; Gartmann, J.; Chu, F.-I.; Nickols, N.G.; Reiter, R.E.; Rettig, M.B.; Marks, L.S.; Ahlering, T.E.; et al. Impact of 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT on the Management of Prostate Cancer Patients with Biochemical Recurrence. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathianathen, N.J.; Furrer, M.A.; Mulholland, C.J.; Katsios, A.; Soliman, C.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Peters, J.S.; Zargar, H.; Costello, A.J.; Hovens, C.M.; et al. Lymphovascular Invasion at the Time of Radical Prostatectomy Adversely Impacts Oncological Outcomes. Cancers 2024, 16, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.-C.; Li, C.-C.; Li, W.-M.; Yeh, H.-C.; Ke, H.-L.; Wu, W.-J.; Chien, T.M.; Wen, S.-C.; Wang, Y.-C.; Lee, H.-Y. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Adjuvant Therapy on Biochemical Recurrence in Prostate Cancer Patients with Positive Surgical Margins after Radical Prostatectomy. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.M.; Tangen, C.M.; Paradelo, J.; Lucia, M.S.; Miller, G.; Troyer, D.; Messing, E.; Forman, J.; Chin, J.; Swanson, G.; et al. Adjuvant Radiotherapy for Pathologically Advanced Prostate CancerA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2006, 296, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.L.; Dalkin, B.L.; True, L.D.; Ellis, W.J.; Stanford, J.L.; Lange, P.H.; Lin, D.W. Positive Surgical Margins at Radical Prostatectomy Predict Prostate Cancer Specific Mortality. J. Urol. 2010, 183, 2213–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeks, J.J.; Eastham, J.A. Radical Prostatectomy: Positive Surgical Margins Matter. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2013, 31, 974–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, A.J.; Eggener, S.E.; Hernandez, A.V.; Klein, E.A.; Kattan, M.W.; Wood, D.P.; Rabah, D.M.; Eastham, J.A.; Scardino, P.T. Do Margins Matter? The Influence of Positive Surgical Margins on Prostate Cancer–Specific Mortality. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Lim, B.; Kyung, Y.S.; Kim, C.-S. Impact of Positive Surgical Margin on Biochemical Recurrence in Localized Prostate Cancer. Prostate Int. 2021, 9, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzenmaier, J.; Pahernik, S.; Tremmel, T.; Haferkamp, A.; Buse, S.; Hohenfellner, M. Positive Surgical Margins after Radical Prostatectomy: Do They Have an Impact on Biochemical or Clinical Progression? BJU Int. 2008, 102, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.H.; Coelho, R.F.; Chauhan, S.; Sivaraman, A.; Schatloff, O.; Cheon, J.; Patel, V.R. Factors Affecting Return of Continence 3 Months after Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: Analysis from a Large, Prospective Data by a Single Surgeon. J. Urol. 2012, 187, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendler, W.P.; Calais, J.; Eiber, M.; Flavell, R.R.; Mishoe, A.; Feng, F.Y.; Nguyen, H.G.; Reiter, R.E.; Rettig, M.B.; Okamoto, S.; et al. Assessment of 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET Accuracy in Localizing Recurrent Prostate Cancer: A Prospective Single-Arm Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandaglia, G.; Albers, P.; Abrahamsson, P.-A.; Briganti, A.; Catto, J.W.F.; Chapple, C.R.; Montorsi, F.; Mottet, N.; Roobol, M.J.; Sønksen, J.; et al. Structured Population-Based Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening for Prostate Cancer: The European Association of Urology Position in 2019. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Negative Margin | Positive Margin | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Scan | Positive Scan | Negative Scan | Positive Scan | NSM (+) Scan vs. PSM (+) Scan | |

| (N = 27) | (N = 74) | (N = 18) | (N = 40) | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age at Surgery | 62.5 (7.22) | 61.0 (6.89) | 62.0 (8.41) | 63.3 (6.11) | 0.0798 |

| Age at PSMA | 68.5 (8.15) | 68.3 (6.36) | 66.7 (7.96) | 66.6 (6.51) | 0.180 |

| Time from Sx to Scan | 5.94 (3.62) | 7.23 (4.71) | 4.69 (4.41) | 3.21 (3.10) | <0.0001 |

| Median [IQR] | 5.10 [3.20–8.70] | 6.95 [3.20–10.8] | 3.73 [2.10–6.60] | 2.20 [0.70–4.80] | |

| PSA at PSMA | 0.78 (0.604) | 2.71 (8.38) | 2.28 (5.32) | 4.62 (10.1) | 0.283 |

| Median [IQR] | 0.70 [0.30–1.00] | 1.20 [0.80–2.10] | 0.94 [0.60–1.30] | 1.37 [1.00–3.30] | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Lesions | 0.476 | ||||

| Negative | 27 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Single | 0 (0%) | 44 (59.5%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (52.5%) | |

| Multiple | 0 (0%) | 30 (40.5%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (47.5%) | |

| Local Recurrence | 0.804 | ||||

| Negative | 27 (100%) | 45 (60.8%) | 18 (100%) | 22 (55.0%) | |

| Prostate bed | 0 (0%) | 25 (33.8%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (40.0%) | |

| Seminal vesical | 0 (0%) | 4 (5.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5.0%) | |

| Lymph Node | 0.732 | ||||

| Negative | 27 (100%) | 29 (39.2%) | 18 (100%) | 17 (42.5%) | |

| At least one node | 0 (0%) | 45 (60.8%) | 0 (0%) | 23 (57.5%) | |

| Bone | 0.411 | ||||

| Negative | 27 (100%) | 62 (83.8%) | 18 (100%) | 31 (77.5%) | |

| At least one lesion | 0 (0%) | 12 (16.2%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (22.5%) | |

| Pathological GGG | 0.133 | ||||

| 1 | 1 (3.7%) | 5 (6.8%) | 3 (16.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 8 (29.6%) | 22 (29.7%) | 4 (22.2%) | 6 (15.0%) | |

| 3 | 11 (40.7%) | 28 (37.8%) | 7 (38.9%) | 18 (45.0%) | |

| 4 | 4 (14.8%) | 7 (9.5%) | 1 (5.6%) | 6 (15.0%) | |

| 5 | 3 (11.1%) | 12 (16.2%) | 3 (16.7%) | 10 (25.0%) | |

| Pathological Stage | 0.0013 | ||||

| pT2 | 15 (55.6%) | 31 (41.9%) | 5 (27.8%) | 5 (12.5%) | |

| pT3/pT4 | 12 (44.4%) | 43 (58.1%) | 13 (72.2%) | 35 (87.5%) | |

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Surgery | 0.96 | 0.91, 1.02 | 0.170 |

| Pathological Gleason Grade Group | |||

| 1 | - | - | |

| 2 | 0.96 | 0.21, 4.59 | 0.959 |

| 3 | 0.68 | 0.15, 3.27 | 0.612 |

| 4 | 0.48 | 0.08, 2.83 | 0.411 |

| 5 | 0.64 | 0.12, 3.53 | 0.598 |

| Pathological Stage | |||

| pT2 | - | - | |

| pT3 | 0.70 | 0.32, 1.54 | 0.374 |

| Margins | |||

| Negative | - | - | |

| Positive | 1.40 | 0.65, 1.54 | 0.382 |

| OR = Odds Ratio; Cl = Confidence Interval | |||

| Negative Margin | Positive Margin | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pT2 | pT3 | pT2 | pT3 | NSM, pT2 vs. PSM, pT2 | NSM, pT3 vs. PSM, pT3 | |

| (N = 46) | (N = 55) | (N = 10) | (N = 48) | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Age at Surgery | 60.2 (7.26) | 62.5 (6.62) | 59.8 (5.78) | 63.5 (6.94) | 0.871 | 0.456 |

| Age at PSMA | 68.4 (7.42) | 68.3 (6.39) | 63.0 (4.34) | 67.4 (7.16) | 0.0313 | 0.502 |

| Time from Sx to Scan | 8.20 (4.29) | 5.78 (4.34) | 3.16 (1.91) | 3.78 (3.85) | <0.001 | 0.0157 |

| Median [Min, Max] | 8.80 [0.400, 18.6] | 4.50 [0.300, 17.1] | 2.98 [1.10, 7.50] | 2.85 [0.192, 18.4] | ||

| PSA at PSMA | 3.05 (10.6) | 1.47 (1.27) | 2.06 (1.75) | 4.28 (9.75) | 0.771 | 0.0366 |

| Median [Min, Max] | 1.05 [0.260, 72.5] | 1.09 [0.140, 6.60] | 1.31 [0.260, 5.80] | 1.14 [0.300, 57.6] | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Lesions | 0.555 | 0.811 | ||||

| Negative | 15 (32.6%) | 12 (21.8%) | 5 (50.0%) | 13 (27.1%) | ||

| Single | 21 (45.7%) | 23 (41.8%) | 3 (30.0%) | 18 (37.5%) | ||

| Multiple | 10 (21.7%) | 20 (36.4%) | 2 (20.0%) | 17 (35.4%) | ||

| Local Recurrence | 0.363 | 0.593 | ||||

| Negative | 31 (67.4%) | 41 (74.5%) | 5 (50.0%) | 35 (72.9%) | ||

| Prostate bed | 14 (30.4%) | 11 (20.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 12 (25.0%) | ||

| Seminal vesical | 1 (2.2%) | 3 (5.5%) | 1 (10.0%) | 1 (2.1%) | ||

| Lymph Node | 0.155 | 0.380 | ||||

| Negative | 31 (67.4%) | 25 (45.5%) | 9 (90.0%) | 26 (54.2%) | ||

| At least one node | 15 (32.6%) | 30 (54.5%) | 1 (10.0%) | 22 (45.8%) | ||

| Bone | 0.897 | 0.768 | ||||

| Negative | 42 (91.3%) | 47 (85.5%) | 9 (90.0%) | 40 (83.3%) | ||

| At least one lesion | 4 (8.7%) | 8 (14.5%) | 1 (10.0%) | 8 (16.7%) | ||

| Pathological GGG | 0.595 | 0.839 | ||||

| 1 | 4 (8.7%) | 2 (3.6%) | 2 (20.0%) | 1 (2.1%) | ||

| 2 | 17 (37.0%) | 13 (23.6%) | 2 (20.0%) | 8 (16.7%) | ||

| 3 | 17 (37.0%) | 22 (40.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 22 (45.8%) | ||

| 4 | 4 (8.7%) | 7 (12.7%) | 2 (20.0%) | 5 (10.4%) | ||

| 5 | 4 (8.7%) | 11 (20.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 12 (25.0%) | ||

| PSMA Scan | 0.303 | 0.536 | ||||

| Negative | 15 (32.6%) | 12 (21.8%) | 5 (50.0%) | 13 (27.1%) | ||

| Positive | 31 (67.4%) | 43 (78.2%) | 5 (50.0%) | 35 (72.9%) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ahlering, T.E.; Hwang, Y.; Lee, M.M.; Tran, J.; Carlson, A.D.J.; Kazarian, L.; Liang, K.; Zhang, W. Assessment of Local and Metastatic Recurrence Following Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy by Margin Status Using PSMA PET/CT Scan. Cancers 2026, 18, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010043

Ahlering TE, Hwang Y, Lee MM, Tran J, Carlson ADJ, Kazarian L, Liang K, Zhang W. Assessment of Local and Metastatic Recurrence Following Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy by Margin Status Using PSMA PET/CT Scan. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhlering, Thomas Edward, Yeagyeong Hwang, Michael Matthew Lee, Joshua Tran, Anders David Jens Carlson, Levon Kazarian, Karren Liang, and Whitney Zhang. 2026. "Assessment of Local and Metastatic Recurrence Following Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy by Margin Status Using PSMA PET/CT Scan" Cancers 18, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010043

APA StyleAhlering, T. E., Hwang, Y., Lee, M. M., Tran, J., Carlson, A. D. J., Kazarian, L., Liang, K., & Zhang, W. (2026). Assessment of Local and Metastatic Recurrence Following Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy by Margin Status Using PSMA PET/CT Scan. Cancers, 18(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010043