Functional Outcomes After Reoperation for Recurrent Glioma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Karnofsky Performance Status with Descriptive Health-Related Quality-of-Life Reporting

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

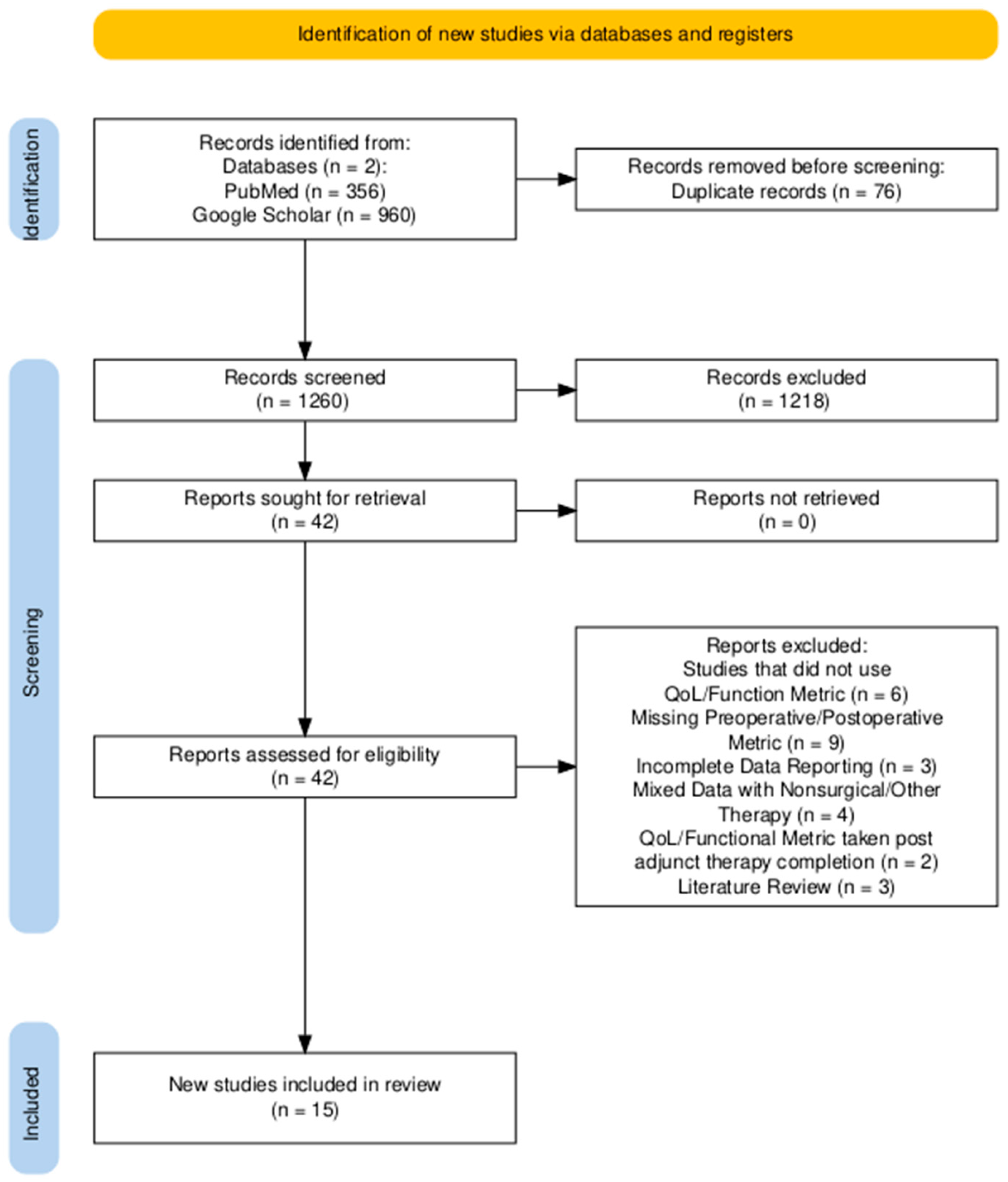

2. Materials and Methods

- PubMed: ((“glioma recurrence” OR “recurrent glioblastoma” OR “relapsed glioma” OR “glioma progression”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“reoperation” OR “repeat surgery” OR “second surgery” OR “surgical reintervention”[All Fields]) AND (“quality of life” OR “health-related quality of life” OR “patient-reported outcomes” OR “functional outcomes”[All Fields])): 23 results.

- PubMed: (“Glioma”[MeSH Terms] OR “Glioma Recurrence”[All Fields] OR “Recurrent Glioma”[All Fields]) AND (“Reoperation”[MeSH Terms] OR “Reoperation”[All Fields] OR “Repeat Surgery”[All Fields] OR “Second Surgery”[All Fields]) AND (“Quality of Life”[MeSH Terms] OR “Health-Related Quality of Life”[All Fields] OR “HRQoL”[All Fields] OR “Functional Outcomes”[All Fields] OR “Patient-Reported Outcomes”[All Fields]): 37 results.

- PubMed: (“Glioma”[MeSH] OR “Glioblastoma”[MeSH] OR “Astrocytoma”[MeSH] OR “Brain Neoplasms”[MeSH]) AND (“Recurrence”[MeSH] OR “Neoplasm Recurrence, Local”[MeSH] OR “Reoperation”[MeSH] OR “Second Surgery”) AND (“Quality of Life”[MeSH] OR “Heath Related Quality of Life” OR “HRQoL”): 252 results.

- PubMed: (“Glioma*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Recurrent Glioma”[Title/Abstract] OR “Glioma Recurrence”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“Postoperative KPS”[All Fields] OR “Postoperative Karnofsky Performance”[All Fields] OR “Karnofsky Performance Scale”[All Fields]) AND (“Reoperation”[Title/Abstract] OR “Repeat Surgery”[Title/Abstract] OR “Surgical Resection”[Title/Abstract]): 45 results.

- Google Scholar: “glioma recurrence” OR “recurrent glioblastoma” OR “relapsed glioma” AND “reoperation” OR “repeat surgery” OR “second surgery” AND “quality of life” OR “health-related quality of life”: 974 results.

- Google Scholar: “health-related quality of life” OR “HRQoL” AND “postoperative recovery” AND (“recurrent glioma” OR “glioma reoperation”): 6 results.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

3.2. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

3.3. QoL Metrics

3.4. Subgroup Analysis of Tumor Grade

4. Discussion

4.1. Functional Outcomes

4.2. Sources of Heterogeneity and Bias

4.3. Multidimensional HRQoL

4.4. Clinical Implications

4.5. Future Directions

4.6. Limitations

4.7. Summary

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| KPS | Karnofsky Performance Scale |

| EQ-5D/EQ5DL | EuroQol 5-Dimension Questionnaire |

| FACT-Cog | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Cognitive Function |

| FACT-G | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General |

| SF-36 | 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey |

| IDH | Isocitrate Dehydrogenase |

| MGMT | O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

| Study | Confounding | Selection of Participants | Classification of Interventions | Deviations from Intended Interventions | Missing Data | Measurement of Outcomes | Selection of Reported Result | Overall Judgment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mukherjee et al., 2020 [26] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Furtak et al., 2022 [16] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Yang et al., 2022 [14] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Li et al., 2021 [25] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Barker et al., 1998 [13] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Ramakrishna et al., 2015 [21] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Koay et al., 2024 [15] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Pinsker et al., 2001 [18] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Ribeiro et al., 2022 [24] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Chen et al., 2016 [20] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Hansen et al., 2024 [17] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Voisin et al., 2022 [23] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Moser, 1988 [22] | Serious | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Salvati et al., 2019 [19] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Rubin et al., 2022 [27] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Investigator | Number of Patients | WHO Grade | Treatment Type | Tumor Location | EOR | QOL Metrics | Median Follow-Up (mo) | Postoperative Deficits: Transient, Permanent, Unspecified | Postoperative Assessment Window (mo) Function/QoL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barker. et al., 1998 [13] | 301 | Grade III–IV = 46 | NR | Reoperation for recurrence | Frontal: 11 Temporal: 12 Parietal: 5 Other: 18 | Subtotal: 33 Gross: 13 | KPS | 15.8 | NR | 4.5 |

| Yang et al., 2022 [14] | 237 | Grade III–IV = 33 | NR | Reoperation for recurrence | Left hemisphere: 14 Right hemisphere: 19 Bilateral/corpus callosum: 0 | Unmatched repeat resection: GTR: 4 STR: 4 Matched repeat resection: GTR: 18 STR: 15 | KPS | NR | New focal neurological deficit, n = 7; all unspecified major vascular infarcts, n = 1; surgical cavity hematoma, n = 1; CNS infection, n = 1; hydrocephalus, n = 1; cognitive impairment, n = 1; sepsis, n = 1; cardiac arrhythmia, n = 1; superficial surgical site infection, n = 1; long bone fracture, n = 1 | 3 |

| Koay et al., 2024 [15] | 44 | Grade III–IV = 20 | NR | Reoperation for high-grade glioma recurrence | Left hemisphere: 14 Right hemisphere: 6 | NR | FACT-G, FACT-Cog | 9 | NR | 0.5 |

| Furtak et al., 2022 [16] | 165 | Grade III–IV = 35 | 37.8 | Reoperation for recurrence | Right temporal lobe: 6 Left temporal lobe: 8 Right parietal lobe: 3 Left parietal lobe: 6 Right frontal lobe: 4 Left frontal lobe: 4 Right occipital lobe: 3 Left occipital lobe: 1 | NR | KPS | 13.1 | NR | 2.5 |

| Hansen et al., 2024 [17] | 66 | Grade III–IV = 66 | Tumor volume >/= 50 cm3: 8 | Reoperation for recurrence | Left side: 34 Recurrence in previous resection cavity wall: 49 Predominant lobe of tumor location: Frontal: 19 Temporal: 15 Parietal: 14 Occipital: 8 Spanning several regions: 10 Bilateral: 2 Ependymal involvement: 35 | EOR at recurrence >/= 95%: 35 | KPS | 9.6 | NR | 3 |

| Pinsker et al., 2001 [18] | 38 | Grade III–IV = 38 | NR | Reoperation for recurrence | Right hemisphere: 23 Left hemisphere: 15 | Total: 21 Subtotal: 17 | KPS | 6 to 54 months | NR | 3.5 |

| Salvati et al., 2019 [19] | 78 | Grade III–IV = 78 | NR | Reoperation for recurrence of high-grade glioma | Surgical procedures in eloquent areas: Total: 45 Language area: 23 Motor area: 22 | GTR: 33 STR: 37 Partial: 8 | KPS | 6.3 | New permanent neurological deficit, n = 2; new transient neurological deficit, n = 17 | 1 |

| Chen et al., 2016 [20] | 65 | Grade III–IV = 20 | NR | Reoperation for recurrence | Laterality: Right: 9 Left: 11 Bilateral: 0 Frontal cortex: 6 Parietal cortex: 8 Temporal cortex: 9 Occipital cortex: 1 Cerebellum: 0 Brainstem: 1 Subcortical (basal ganglia, thalamus, corpus callosum): 5 Eloquent/critical area involvement: 6 | GTR: 10 NTR: 8 STR: 2 | KPS, ADL | 9 | NR | 1.5 |

| Ramakrishna et al., 2015 [21] | 52 | NR | NR | Reoperation for recurrence | Frontal: 29 Inula: 7 Temporal: 17 Parietal: 5 Left side: 24 Right side: 34 Crossing midline: Yes: 7 No: 45 | <50%: 0 50–90%: 14 > 90%: 38 | KPS | 18 | NR | 3–6 |

| Moser et al., 1988 [22] | 17 | Grade III–IV = 11 | NR | Reoperation for recurrence | NR | NR | KPS | 12.4 | NR | 31 |

| Voisin et al., 2022 [23] | 174 | Grade III–IV = 87 | NR | Reoperation for recurrence | Frontal: 27 Occipital: 6 Parietal: 20 Temporal: 34 | Biopsy: 0 STR (<90%): 38 GTR (>/=90%): 49 | KPS | 111.6 | NR | 3 |

| Ribeiro et al., 2022 [24] | 80 | Grade I–II = 20 | 82.8 | Reoperation for recurrence of low-grade glioma | Rt insula/paralimbic: 34 Lt insula/paralimbic: 46 | Mean: 83.7% +/− 9.9% Total: 1 Subtotal: 15 Partial: 4 | KPS | NR | All unspecified worsening of neurological conditions, n = 9; language disorder, n = 1; epileptic status, n = 7 | 3 |

| Li et al., 2021 [25] | 225 | Grade I–II = 71 Grade III–IV = 154 | 40.62 | Reoperation for recurrence: awake craniotomy or general anesthesia craniotomy | Frontal: 115 Temporal: 97 Parietal: 13 | 94.89 | KPS | NR | All unspecified early postoperative deficits, n = 44; late postoperative neurological deficits, n = 24 | 3 |

| Mukherjee et al., 2020 [26] | 312 | Grade III–IV = 145 | NR | Reoperation for recurrence | Right side: 74 Left side: 71 Frontal: 62 Temporal: 25 Parietal: 33 Occipital: 25 | Gross total (n = 88) Subtotal (n = 57) > 90% resection: 20 80–90%: 17 < 80%: 20 | SF-36 | 190.8 | All unspecified motor weaknesses, n = 1; speech deficit, n = 1 | 4 |

| Rubin et al., 2022 [27] | 225 | Grade III–IV = 65 | 14.91 | Reoperation for recurrence | NR | Gross total (n): 24 Near-total: 28 Subtotal: 23 | EQ-5D Index | 10.4 | All unspecified language or motor deficits, n = 8 | 1 |

References

- Mesfin, F.B.; Karsonovich, T.; Al-Dhahir, M.A. Gliomas. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441874/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Zhou, X.; Liao, X.; Zhang, B.; He, H.; Shui, Y.; Xu, W.; Jiang, C.; Shen, L.; Wei, Q. Recurrence patterns in patients with high-grade glioma following temozolomide-based chemoradiotherapy. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 5, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, M.; van den Bent, M.; Preusser, M.; Le Rhun, E.; Tonn, J.C.; Minniti, G.; Bendszus, M.; Balana, C.; Chinot, O.; Dirven, L.; et al. EANO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse gliomas of adulthood. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaz-Salgado, M.A.; Villamayor, M.; Albarrán, V.; Alía, V.; Sotoca, P.; Chamorro, J.; Rosero, D.; Barrill, A.M.; Martín, M.; Fernandez, E.; et al. Recurrent glioblastoma: A review of the treatment options. Cancers 2023, 15, 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervey-Jumper, S.L.; Berger, M.S. Reoperation for recurrent high-grade glioma: A current perspective of the literature. Neurosurgery 2014, 75, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalabi, O.T.; Dao Trong, P.; Kaes, M.; Jakobs, M.; Kessler, T.; Oehler, H.; König, L.; Eichkorn, T.; Sahm, F.; Debus, J.; et al. Repeat surgery of recurrent glioma for molecularly informed treatment in the age of precision oncology: A risk-benefit analysis. J. Neuro Oncol. 2024, 167, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarti, S.; Gupta, S.R.; Myneni, S.; Elshareif, M.; Rogers, J.L.; Caraway, C.; Ahmed, A.K.; Schreck, K.C.; Kamson, D.O.; Holdhoff, M.; et al. Clinical outcome assessment tools for evaluating the management of gliomas. Cancers 2025, 17, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witt Hamer, P.C.; Klein, M.; Hervey-Jumper, S.L.; Wefel, J.S.; Berger, M.S. Functional outcomes and health-related quality of life following glioma surgery. Neurosurgery 2021, 88, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasagasako, T.; Ueda, A.; Mineharu, Y.; Mochizuki, Y.; Doi, S.; Park, S.; Terada, Y.; Sano, N.; Tanji, M.; Arakawa, Y.; et al. Postoperative Karnofsky performance status prediction in patients with IDH wild-type glioblastoma: A multimodal approach. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, M.; Adali, N. Neurocognitive state and quality of life of patients with glioblastoma in Mediterranean countries: A systematic review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 11980–11993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, F.G.; Chang, S.M.; Gutin, P.H.; Malec, M.K.; McDermott, M.W.; Prados, M.D.; Wilson, C.B. Survival and functional status after resection of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Neurosurgery 1998, 42, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Ellenbogen, Y.; Martyniuk, A.; Sourour, M.; Takroni, R.; Somji, M.; Gardiner, E.; Hui, K.; Odedra, D.; Larrazabal, R.; et al. Reoperation in adult patients with recurrent glioblastoma: A matched cohort analysis. Neuro Oncol. Adv. 2022, 4, vdac115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koay, J.M.; Michaelides, L.; Moniz-Garcia, D.P.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A.; Chaichana, K.; Almeida, J.P.; Gruenbaum, B.F.; Sherman, W.J.; Sabsevitz, D.S. Repeated surgical resections for management of high-grade glioma and its impact on quality of life. J. Neuro Oncol. 2024, 167, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtak, J.; Kwiatkowski, A.; Śledzińska, P.; Bebyn, M.; Krajewski, S.; Szylberg, T.; Birski, M.; Druszcz, A.; Krystkiewicz, K.; Gasiński, P.; et al. Survival after reoperation for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: A prospective study. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 42, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.T.; Jacobsen, K.S.; Kofoed, M.S.; Petersen, J.K.; Boldt, H.B.; Dahlrot, R.H.; Schulz, M.K.; Poulsen, F.R. Prognostic factors to predict postoperative survival in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. World Neurosurg. X 2024, 23, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsker, M.; Lumenta, C. Experiences with reoperation on recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Zentralbl. Neurochir. 2001, 62, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, M.; Pesce, A.; Palmieri, M.; Brunetto, G.M.F.; Santoro, A.; Frati, A. The role and real effect of an iterative surgical approach for the management of recurrent high-grade glioma: An observational analytic cohort study. World Neurosurg. 2019, 124, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.W.; Morsy, A.A.; Liang, S.; Ng, W.H. Re-do craniotomy for recurrent grade IV glioblastomas: Impact and outcomes from the National Neuroscience Institute Singapore. World Neurosurg. 2016, 87, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, R.; Hebb, A.; Barber, J.; Rostomily, R.; Silbergeld, D. Outcomes in reoperated low-grade gliomas. Neurosurgery 2015, 77, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, R.P. Surgery for glioma relapse: Factors that influence a favorable outcome. Cancer 1988, 62, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voisin, M.R.; Zuccato, J.A.; Wang, J.Z.; Zadeh, G. Surgery for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: A retrospective case control study. World Neurosurg. 2022, 166, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, L.; Ng, S.; Duffau, H. Recurrent insular low-grade gliomas: Factors guiding the decision to reoperate. J. Neurosurg. 2022, 138, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.C.; Chiu, H.Y.; Wei, K.C.; Lin, Y.J.; Chen, K.T.; Hsu, P.W.; Huang, Y.C.; Chen, P.Y. Using cortical function mapping by awake craniotomy dealing with the patient with recurrent glioma in the eloquent cortex. Biomed. J. 2021, 44, S48–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Wood, J.; Liaquat, I.; Stapleton, S.R.; Martin, A.J. Craniotomy for recurrent glioblastoma: Is it justified? A comparative cohort study with outcomes over 10 years. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 188, 105568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, M.C.; Sagberg, L.M.; Jakola, A.S.; Solheim, O. Primary versus recurrent surgery for glioblastoma—A prospective cohort study. Acta Neurochir. 2022, 164, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, G.; Chemaitelly, H.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Rücker, G. Seriously misleading results using inverse of Freeman–Tukey transformation in meta-analysis of single proportions. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 10, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, J.A.; Marín-Martínez, F.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Van den Noortgate, W.; Viechtbauer, W. Estimation of the predictive power of the model in mixed-effects meta-regression: A simulation study. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2014, 67, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Opijnen, M.P.; Sadigh, Y.; E Dijkstra, M.; Young, J.S.; Krieg, S.M.; Ille, S.; Sanai, N.; Rincon-Torroella, J.; Maruyama, T.; Schucht, P.; et al. The impact of intraoperative mapping during re-resection in recurrent gliomas: A systematic review. J. Neuro Oncol. 2025, 171, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffau, H. Repeated Awake Surgical Resection(s) for Recurrent Diffuse Low-Grade Gliomas: Why, When, and How to Reoperate? Front. Oncol. 2022, 13, 947933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandonnet, E.; De Witt Hamer, P.; Poisson, I.; Whittle, I.; Bernat, A.-L.; Bresson, D.; Madadaki, C.; Bouazza, S.; Ursu, R.; Carpentier, A.F.; et al. Initial experience using awake surgery for glioma: Oncological, functional, and employment outcomes in a consecutive series of 25 cases. Neurosurgery 2015, 76, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffau, H.; Mandonnet, E. The “onco-functional balance” in surgery for diffuse low-grade glioma: Integrating the extent of resection with quality of life. Acta Neurochir. 2013, 155, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervey-Jumper, S.L.; Berger, M.S. Maximizing safe resection of low- and high-grade glioma. J. Neuro Oncol. 2016, 130, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffau, H. Long-term outcomes after supratotal resection of diffuse low-grade gliomas: A consecutive series with 11-year follow-up. Acta Neurochir. 2016, 158, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almairac, F.; Duffau, H. Awake surgery with direct electrical stimulation mapping and real-time cognitive monitoring for functionally guided tumor resection: How we do it. Acta Neurochir. 2025, 167, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taphoorn, M.J.; Sizoo, E.M.; Bottomley, A. Review on quality of life issues in patients with primary brain tumors. Oncol. 2010, 15, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, A.E.; Wu, Y.; Benz, L.S.; Verhaak, R.G.W.; Kwan, B.M.; Claus, E.B. Quality of life after surgery for lower grade gliomas. Cancer 2023, 129, 3761–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffau, H.; Capelle, L.; Denvil, D.; Sichez, N.; Gatignol, P.; Lopes, M.; Mitchell, M.C.; Sichez, J.P.; Van Effenterre, R. Functional recovery after surgical resection of low-grade gliomas in eloquent brain: Hypothesis of brain compensation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2003, 74, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.; Rigau, V.; Moritz-Gasser, S.; Gozé, C.; Darlix, A.; Herbet, G.; Duffau, H. Long-term autonomy, professional activities, cognition, and overall survival after awake functional-based surgery in patients with IDH-mutant grade 2 gliomas: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 46, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyk, K.V.; Crespi, C.M.; Petersen, L.; Ganz, P.A. Identifying cancer-related cognitive impairment using the FACT-Cog Perceived Cognitive Impairment. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019, 4, pkz099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagberg, L.M.; Jakola, A.S.; Solheim, O. Quality of life assessed with EQ-5D in patients undergoing glioma surgery: What is the responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference? Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunevicius, A. Reliability and validity of the SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire in patients with brain tumors: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.-H.; Wang, Z.-F.; Pan, Z.-Y.; Péus, D.; Delgado-Fernandez, J.; Pallud, J.; Li, Z.-Q. A meta-analysis of survival outcomes following reoperation in recurrent glioblastoma: Time to consider the timing of reoperation. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shofty, B.; Haim, O.; Costa, M.; Kashanian, A.; Shtrozberg, S.; Ram, Z.; Grossman, R. Impact of repeated operations for progressive low-grade gliomas. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 2331–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Number of Patients | 947 |

|---|---|

| Mean age in yrs (SD) | 49.18 ± 12.13 |

| Gender | |

| M | 540 (61.4%) |

| F | 339(38.6%) |

| WHO grade | |

| I–II | 149 (15.7%) |

| III–IV | 798 (84.3%) |

| Average tumor size (cm3) a | 45.23 |

| Presenting symptoms b | |

| Seizure | 163 (36.6%) |

| Headache | 131 (29.4%) |

| Miscellaneous neuro-dysfunction | 52 (11.7%) |

| Cognitive deficit | 41 (9.2%) |

| Motor deficit | 34 (7.6%) |

| Brain edema | 13 (2.9%) |

| Speech disorder | 9 (2.0%) |

| CN lesion | 2 (0.45%) |

| Adjunct therapy completed after surgery c | |

| Chemotherapy | 184 (33.6%) |

| Brachytherapy or radiotherapy | 105 (19.2%) |

| Radiotherapy + chemotherapy | 258 (47.2%) |

| Location d | |

| Frontal | 227 (25.3%) |

| Temporal | 223 (24.8%) |

| Parietal | 107 (11.9%) |

| Occipital | 44 (4.9%) |

| R hemisphere | 48 (5.3%) |

| L hemisphere | 43 (4.8%) |

| Insula/paralimbic | 87 (9.7%) |

| Eloquent location | 80 (8.9%) |

| Other | 40 (4.4%) |

| EOR e | |

| GTR | 421 (47.6%) |

| NTR | 74 (8.4%) |

| STR | 363 (41.0%) |

| Partial | 27 (3.1%) |

| Average median follow-up (months) f | 13.1 (6.3–190) |

| Surgical complications g | 74 |

| Surgical site infection | 12 (16.2%) |

| Hydrocephalus | 6 (8.1%) |

| Hemorrhage | 3 (4.1%) |

| Meningitis | 1 (1.4%) |

| Liquorrhea requiring surgical intervention | 1 (1.4%) |

| Hematoma | 4 (5.4%) |

| Transient increase in neurological deficits | 3 (4.1%) |

| Seizure | 2 (2.7%) |

| Unspecified | 37 (50.0%) |

| Postoperative deficits h | 132 |

| Motor/language deficit | 10 (7.6%) |

| Permanent neurological deficit | 2 (1.5%) |

| Transient neurological deficit | 17 (12.9%) |

| Unspecified | 103 (78.0%) |

| QOL Metric Used | Number of Times Utilized |

|---|---|

| KPS | 13 (81.2%) |

| SF-36 | 1 (6.3%) |

| FACT-G/Cog | 1 (6.3%) |

| EQ-5D | 1 (6.3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Brekke-Kumley, B.; Chebaro, K.; Cler, K.; Fox, M.; Lather, M.; Balusu, C.; Kinder, P.R. Functional Outcomes After Reoperation for Recurrent Glioma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Karnofsky Performance Status with Descriptive Health-Related Quality-of-Life Reporting. Cancers 2026, 18, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010042

Brekke-Kumley B, Chebaro K, Cler K, Fox M, Lather M, Balusu C, Kinder PR. Functional Outcomes After Reoperation for Recurrent Glioma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Karnofsky Performance Status with Descriptive Health-Related Quality-of-Life Reporting. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrekke-Kumley, Brooklyn, Kamel Chebaro, Kristin Cler, Mackenzie Fox, Madison Lather, Chinmayi Balusu, and Pamela R. Kinder. 2026. "Functional Outcomes After Reoperation for Recurrent Glioma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Karnofsky Performance Status with Descriptive Health-Related Quality-of-Life Reporting" Cancers 18, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010042

APA StyleBrekke-Kumley, B., Chebaro, K., Cler, K., Fox, M., Lather, M., Balusu, C., & Kinder, P. R. (2026). Functional Outcomes After Reoperation for Recurrent Glioma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Karnofsky Performance Status with Descriptive Health-Related Quality-of-Life Reporting. Cancers, 18(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010042