Therapeutic Potential of CAR-CIK Cells in Acute Leukemia Relapsed Post Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Donor Lymphocyte Infusions (DLI)

1.2. Cytokine-Induced Killer (CIK) Cells

1.3. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cells

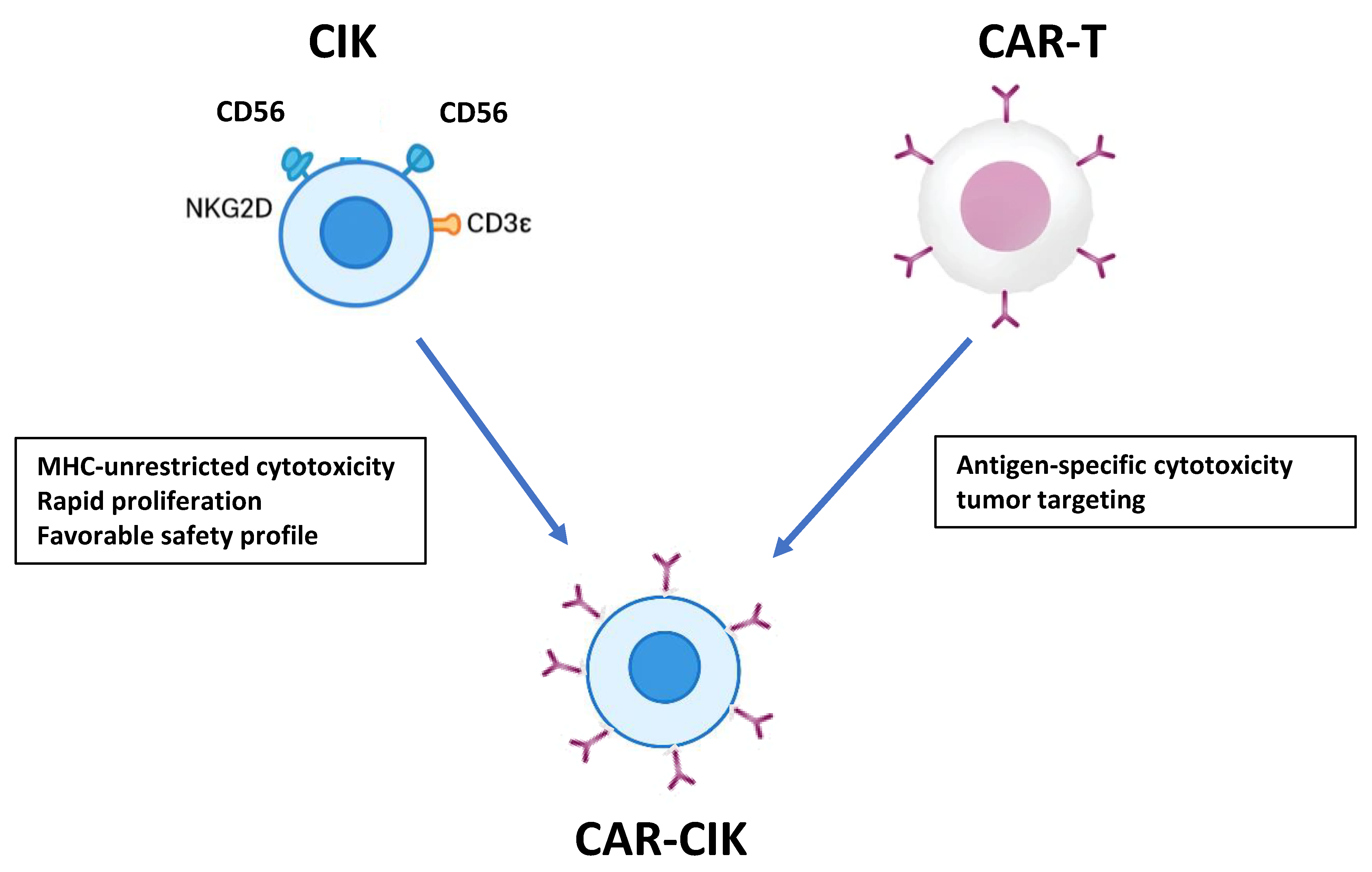

1.4. CAR-CIK Cells

2. CAR-CIK in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

3. CAR-CIK in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fielding, A.K.; Richards, S.M.; Chopra, R.; Lazarus, H.M.; Luger, S.M.; Buck, G.; Rowe, J.M.; Goldstone, A.H.; Fenaux, P.; Sanz, M.A.; et al. Outcome of 609 Adults After Relapse of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL). Blood 2007, 109, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriol, A.; Vives, S.; Hernández-Rivas, J.Á.; González, M.; González, M.; Ribera, J.; Vallespí, T.; Bermudez, A.; Sanz, M.A. Outcome after relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adult patients. Haematologica 2010, 95, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, L.M.; Bassett, R., Jr.; Rondon, G.; Hamdi, A.; Qazilbash, M.; Hosing, C.; Jones, R.B.; Shpall, E.J.; Popat, U.R.; Nieto, Y.; et al. Outcomes of second allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bataller, A.; Kantarjian, H.; Bazinet, A.; Kadia, T.; Daver, N.; DiNardo, C.D.; Borthakur, G.; Loghavi, S.; Patel, K.; Tang, G.; et al. Outcomes and genetic dynamics of acute myeloid leukemia at first relapse. Haematologica 2024, 109, 3543–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bejanyan, N.; Weisdorf, D.J.; Logan, B.R.; Wang, H.L.; Devine, S.M.; de Lima, M.; Bunjes, D.W.; Zhang, M.J. Survival of patients with acute myeloid leukemia relapsing after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: A Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research study. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015, 21, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Rybicki, L.; Corrigan, D.; Hamilton, B.K.; Sobecks, R.; Kalaycio, M.; Gerds, A.T.; Dean, R.M.; Hill, B.T.; Pohlman, B.; et al. Survival following relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes in the contemporary era. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Ther. 2021, 14, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devillier, R.; Crocchiolo, R.; Etienne, A.; Prebet, T.; Charbonnier, A.; Fürst, S.; El-Cheikh, J.; D’Incan, E.; Rey, J.; Faucher, C.; et al. Outcome of relapse after allogeneic stem cell transplant in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2013, 54, 1228–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominietto, A.; Pozzi, S.; Miglino, M.; Albarracin, F.; Piaggio, G.; Bertolotti, F.; Grasso, R.; Zupo, S.; Raiola, A.M.; Gobbi, M.; et al. Donor lymphocyte infusions for the treatment of minimal residual disease in acute leukemia. Blood 2007, 109, 5063–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, C.; Labopin, M.; Schaap, N.; Veelken, H.; Schleuning, M.; Stadler, M.; Finke, J.; Hurst, E.; Baron, F.; Ringden, O.; et al. Prophylactic donor lymphocyte infusion after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in acute leukaemia—A matched pair analysis by the Acute Leukaemia Working Party of EBMT. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 184, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, F.; Le Floch, A.-C.; Granata, A.; Fürst, S.; Faucher, C.; Lemarie, C.; Harbi, S.; Bramanti, S.; Calmels, B.; El-Cheikh, J.; et al. Prophylactic donor lymphocyte infusion after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for high-risk AML. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016, 52, 620–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takami, A.; Okumura, H.; Yamazaki, H.; Kami, M.; Kim, S.-W.; Asakura, H.; Endo, T.; Nishio, M.; Minauchi, K.; Kumano, K.; et al. Prospective Trial of High-Dose Chemotherapy Followed by Infusions of Peripheral Blood Stem Cells and Dose-Escalated Donor Lymphocytes for Relapsed Leukemia after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Int. J. Hematol. 2005, 82, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaldi, A.; Biagi, E.; Bonini, C.; Biondi, A.; Introna, M. Cell-based strategies to manage leukemia relapse: Efficacy and feasibility of immunotherapy approaches. Leukemia 2014, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Yang, L.; Yuan, X.; Huang, H.; Luo, Y. Optimization of Donor Lymphocyte Infusion for AML Relapse After Allo-HCT in the Era of New Drugs and Cell Engineering. Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 790299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliuca, S.; Schmid, C.; Santoro, N.; Simonetta, F.; Battipaglia, G.; Guillaume, T.; Greco, R.; Onida, F.; Sánchez-Ortega, I.; Yakoub-Agha, I.; et al. Donor lymphocyte infusion after allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation for haematological malignancies: Basic considerations and best practice recommendations from the EBMT. Lancet Haematol. 2024, 11, e448–e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Wolf, I.G.; Negrin, R.S.; Kiem, H.P.; Blume, K.G.; Weissman, I.L. Use of a SCID mouse/human lymphoma model to evaluate cytokine-induced killer cells with potent antitumor cell activity. J. Exp. Med. 1991, 174, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.; Verneris, M.R.; Ito, M.; Shizuru, J.A.; Negrin, R.S. Expansion of cytolytic CD8+ natural killer T cells with limited capacity for graft-versus-host disease induction due to interferon γ production. Blood 2001, 97, 2923–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verneris, M.R.; Ito, M.; Baker, J.; Arshi, A.; Negrin, R.S.; Shizuru, J.A. Engineering hematopoietic grafts: Purified allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells plus expanded CD8+ NK-T cells in the treatment of lymphoma. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001, 7, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pievani, A.; Borleri, G.; Pende, D.; Moretta, L.; Rambaldi, A.; Golay, J.; Introna, M. Dual-functional capability of CD3+CD56+ CIK cells, a T-cell subset that acquires NK function and retains TCR-mediated specific cytotoxicity. Blood 2011, 118, 3301–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introna, M.; Golay, J.; Rambaldi, A. Cytokine Induced Killer (CIK) cells for the treatment of haematological neoplasms. Immunol. Lett. 2013, 155, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbari Sevari, F.; Mehdizadeh, A.; Abbasi, K.; Hejazian, S.S.; Raeisi, M. Cytokine-induced killer cells: New insights for therapy of hematologic malignancies. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rettinger, E. Cytokine-Induced Killer Cells: A Unique Platform for Adoptive Cell Immunotherapy after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2024, 52, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Introna, M.; Lussana, F.; Algarotti, A.; Gotti, E.; Valgardsdottir, R.; Micò, C.; Grassi, A.; Pavoni, C.; Ferrari, M.L.; Delaini, F.; et al. Phase II Study of Sequential Infusion of Donor Lymphocyte Infusion and Cytokine-Induced Killer Cells for Patients Relapsed after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017, 23, 2070–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merker, M.; Salzmann-Manrique, E.; Katzki, V.; Huenecke, S.; Bremm, M.; Bakhtiar, S.; Willasch, A.; Jarisch, A.; Soerensen, J.; Schulz, A.; et al. Clearance of Hematologic Malignancies by Allogeneic Cytokine-Induced Killer Cell or Donor Lymphocyte Infusions. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019, 25, 1281–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüm, P.; Kayser, S. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-Cell Therapy in Hematologic Malignancies: Clinical Implications and Limitations. Cancers 2024, 16, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Rivière, I. Clinical manufacturing of CAR T cells: Foundation of a promising therapy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2016, 3, 16015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maude, S.L.; Frey, N.; Shaw, P.A.; Aplenc, R.; Barrett, D.M.; Bunin, N.J.; Chew, A.; Gonzalez, V.E.; Zheng, Z.; Lacey, S.F.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelapu, S.S.; Locke, F.L.; Bartlett, N.L.; Lekakis, L.J.; Miklos, D.B.; Jacobson, C.A.; Braunschweig, I.; Oluwole, O.O.; Siddiqi, T.; Lin, Y.; et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2531–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, F.L.; Miklos, D.B.; Jacobson, C.A.; Perales, M.-A.; Kersten, M.-J.; Oluwole, O.O.; Ghobadi, A.; Rapoport, A.P.; McGuirk, J.; Pagel, J.M.; et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Munoz, J.; Goy, A.; Locke, F.L.; Jacobson, C.A.; Hill, B.T.; Timmerman, J.M.; Holmes, H.; Jaglowski, S.; Flinn, I.W.; et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-Cell Therapy in Relapsed or Refractory Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, N.; Berdeja, J.; Lin, Y.; Siegel, D.; Jagannath, S.; Madduri, D.; Liedtke, M.; Rosenblatt, J.; Maus, M.V.; Turka, A.; et al. Anti-BCMA CAR T-Cell Therapy bb2121 in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1726–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddie, C.; Sandhu, K.S.; Tholouli, E.; Logan, A.C.; Shaughnessy, P.; Barba, P.; Ghobadi, A.; Guerreiro, M.; Yallop, D.; Abedi, M.; et al. Obecabtagene Autoleucel in Adults with B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 2219–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laetsch, T.W.; Maude, S.L.; Rives, S.; Hiramatsu, H.; Bittencourt, H.; Bader, P.; Baruchel, A.; Boyer, M.; De Moerloose, B.; Qayed, M.; et al. Three-Year Update of Tisagenlecleucel in Pediatric and Young Adult Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in the ELIANA Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1664–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.D.; Cassaday, R.D.; Park, J.H.; Houot, R.; Logan, A.C.; Boissel, N.; Leguay, T.; Bishop, M.R.; Topp, M.S.; O’Dwyer, K.M.; et al. Three-year analysis of adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with Brexucabtagene autoleucel in ZUMA-3. Leukemia 2025, 39, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Huang, X.; Ma, H.; Wang, H.; Xiao, L. Limitations of CAR-T Cell Therapy in Hematologic Malignancies: Focusing on Antigen Escape and T-Cell Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisani, I.; Melita, G.; de Souza, P.B.; Galimberti, S.; Savino, A.M.; Sarno, J.; Landoni, B.; Crippa, S.; Gotti, E.; Cuofano, C.; et al. Optimized GMP-grade production of non-viral Sleeping Beauty-generated CARCIK cells for enhanced fitness and clinical scalability. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, C.F.; Gaipa, G.; Lussana, F.; Belotti, D.; Gritti, G.; Napolitano, S.; Matera, G.; Cabiati, B.; Buracchi, C.; Borleri, G.; et al. Sleeping Beauty–engineered CAR T cells achieve antileukemic activity without severe toxicities. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 6021–6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaninelli, S.; Panna, S.; Tettamanti, S.; Melita, G.; Doni, A.; D’Autilia, F.; Valgardsdottir, R.; Gotti, E.; Rambaldi, A.; Golay, J.; et al. Functional activity of cytokine-induced killer cells enhanced by CAR-CD19 modification or by soluble bispecific antibody blinatumomab. Antibodies 2024, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, H.; Shi, Z.; Gao, F.; Shi, J.; Luo, Y.; Yu, J.; Lai, X.; Fu, H.; Liu, L.; et al. Prognostic factors and clinical outcomes in patients with relapsed acute leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2023, 58, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferra Coll, C.; Morgades de la Fe, M.; Prieto García, L.; Vaz, C.P.; Heras Fernando, M.I.; Bailen Almorox, R.; Garcia-Cadenas, I.; Calabuig Muñoz, M.; Ripa, T.Z.; Zanabili Al-Sibai, J.; et al. Prognosis of Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia Relapsing after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Eur. J. Haematol. 2023, 110, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introna, M.; Borleri, G.; Conti, E.; Franceschetti, M.; Barbui, A.M.; Broady, R.; Dander, E.; Gaipa, G.; D’amico, G.; Biagi, E.; et al. Repeated infusions of donor-derived cytokine-induced killer cells in patients relapsing after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: A phase I study. Haematologica 2007, 92, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettinger, E.; Huenecke, S.; Bonig, H.; Merker, M.; Jarisch, A.; Soerensen, J.; Willasch, A.; Bug, G.; Schulz, A.; Klingebiel, T.; et al. Interleukin-15-activated cytokine-induced killer cells may sustain remission in leukemia patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: Feasibility, safety and first insights on efficacy. Haematologica 2016, 101, e153–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussana, F.; Introna, M.; Golay, J.; Delaini, F.; Pavoni, C.; Valgarsddottir, R.; Gotti, E.; Algarotti, A.; Micò, C.; Grassi, A.; et al. Final Analysis of a Multicenter Pilot Phase 2 Study of Cytokine Induced Killer (CIK) Cells for Patients with Relapse after Allogeneic Transplantation. Blood 2016, 128, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivics, Z.; Hackett, P.B.; Plasterk, R.H.; Izsvák, Z. Molecular Reconstruction of Sleeping Beauty, a Tc1-like Transposon from Fish, and Its Transposition in Human Cells. Cell 1997, 91, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, A.; Ponzo, M.; Nicolette, C.A.; Tcherepanova, I.Y.; Biondi, A.; Magnani, C.F. The Past, Present, and Future of Non-Viral CAR T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 867013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, C.F.; Mezzanotte, C.; Cappuzzello, C.; Bardini, M.; Tettamanti, S.; Fazio, G.; Cooper, L.J.; Dastoli, G.; Cazzaniga, G.; Biondi, A.; et al. Preclinical Efficacy and Safety of CD19CAR Cytokine-Induced Killer Cells Transfected with Sleeping Beauty Transposon for the Treatment of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lussana, F.; Magnani, C.F.; Galimberti, S.; Gritti, G.; Gaipa, G.; Belotti, D.; Cabiati, B.; Napolitano, S.; Ferrari, S.; Moretti, A.; et al. Donor-derived CARCIK-CD19 cells engineered with Sleeping Beauty transposon in acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapsed after allogeneic transplantation. Blood Cancer J. 2025, 15, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debenedette, M.; Purdon, T.J.; McCloud, J.R.; Plachco, A.; Norris, M.; Gamble, A.; Krisko, J.F.; Tcherepanova, I.Y.; Nicolette, C.A.; Brentjens, R. CD19-CAR Cytokine Induced Killer Cells Armored with IL-18 Control Tumor Burden, Prolong Mouse Survival and Result in In Vivo Persistence of CAR-CIK Cells in a Model of B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Blood 2023, 142, 6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerushalmi, Y.; Shem-Tov, N.; Danylesko, I.; Canaani, J.; Avigdor, A.; Yerushalmi, R.; Nagler, A.; Shimoni, A. Second hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as salvage therapy for relapsed acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndromes after a first transplantation. Haematologica 2022, 108, 1782–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, V.; Pizzitola, I.; Agostoni, V.; Attianese, G.M.P.G.; Finney, H.; Lawson, A.; Pule, M.; Rousseau, R.; Biondi, A.; Biagi, E. Cytokine-induced killer cells for cell therapy of acute myeloid leukemia: Improvement of their immune activity by expression of CD33-specific chimeric receptors. Haematologica 2010, 95, 2144–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, G.; Arsuffi, C.; Pievani, A.; Salerno, D.; Mantegazza, F.; Dazzi, F.; Biondi, A.; Tettamanti, S.; Serafini, M. Engineering tandem CD33xCD146 CAR CIK (cytokine-induced killer) cells to target the acute myeloid leukemia niche. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1192333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondi, M.; Tettamanti, S.; Galimberti, S.; Cerina, B.; Tomasoni, C.; Piazza, R.; Donsante, S.; Bido, S.; Perriello, V.M.; Broccoli, V.; et al. Selective homing of CAR-CIK cells to the bone marrow niche enhances control of the Acute Myeloid Leukemia burden. Blood 2023, 141, 2587–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canichella, M.; Molica, M.; Mazzone, C.; de Fabritiis, P. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: State of the Art and Recent Advances. Cancers 2023, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depil, S.; Duchateau, P.; Grupp, S.A.; Mufti, G.; Poirot, L. ‘Off-the-shelf’ allogeneic CAR T cells: Development and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, S.; Aplenc, R.; Baumeister, S.H.; Becilli, M.; Bhagwat, A.S.; Bonifant, C.L.; Budde, L.E.; Chien, C.D.; Curran, K.J.; Daniyan, A.F.; et al. International Consensus Guidelines for the Conduct and Reporting of CAR T-Cell Clinical Trials in AML. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 6047–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | DLI | CIK | CAR-CIK |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Donor T cells | Donor T/NK-like cells expanded ex vivo | Donor CIK cells genetically engineered with CAR |

| Antileukemic effect | GvL effect, moderate | Broader GvL effect, NK-like cytotoxicity | Potent, antigen-specific cytotoxicity plus NK-like activity |

| Alloreactivity/GvHD risk | High | Low to moderate | Low (maintained safety of CIK platform) |

| Target specificity | Non-specific | Limited | CAR-directed, antigen-specific (e.g., CD19, CD33) |

| Persistence | Short to moderate | Moderate | Improved persistence depending on CAR and modifications (e.g., CXCR4) |

| Microenvironmental targeting | None | Limited | Can be engineered (e.g., CD33xCD146 tandem CAR for AML niche targeting) |

| Manufacturing complexity | Minimal | Moderate (ex vivo expansion) | High (requires CAR transduction, possibly transposon or viral vectors) |

| Clinical use post-transplant | Relapse treatment, prophylaxis limited | Relapse prevention/treatment | Relapse prevention/treatment, potentially safer than CAR-T |

| Type of Study | Model/Population | CAR Target | Findings | Safety/GvHD | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I/II CARCIK-SB (early experience reported) | 13 (4 pediatric, 9 adult) | CD19-CAR | CR/CRi in 6/7 at highest dose; robust expansion; CAR detectable up to 10 months | 2 CRS G1, 1 × CRS G2; no GVHD reported | [45] |

| CARCIK (NCT03389035/FT01/FT02/FT03) | 36 (4 pediatric, 32 adult) | CD19-CAR | Durable response; 1-year OS 57%, 1-year EFS 32%; 83% ORR, 86% MRD-neg CR | Mostly low-grade toxicity; no GVHD observed; 15/36 had CRS ≤ G2; ICANS G2 in 1; late peripheral neurotox G3 in 2 | [46] |

| Type of Study | Model/Population | CAR Target | Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| preclinical | In vitro AML + stromal co-culture | Tandem CD33 × CD146 | Demonstrates microenvironment targeting, dual CAR approach | [50] |

| preclinical | AML xenograft murine models | CD33-CAR + CXCR4 | Highlights importance of homing and niche targeting for durable effect | [51] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Canichella, M.; de Fabritiis, P.; Abruzzese, E. Therapeutic Potential of CAR-CIK Cells in Acute Leukemia Relapsed Post Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Cancers 2026, 18, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010032

Canichella M, de Fabritiis P, Abruzzese E. Therapeutic Potential of CAR-CIK Cells in Acute Leukemia Relapsed Post Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanichella, Martina, Paolo de Fabritiis, and Elisabetta Abruzzese. 2026. "Therapeutic Potential of CAR-CIK Cells in Acute Leukemia Relapsed Post Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation" Cancers 18, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010032

APA StyleCanichella, M., de Fabritiis, P., & Abruzzese, E. (2026). Therapeutic Potential of CAR-CIK Cells in Acute Leukemia Relapsed Post Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Cancers, 18(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010032