Association of a CD44s-v5-v6 Null Phenotype with Advanced Stage Cholangiocarcinoma: A Preliminary Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement and Study Cohort

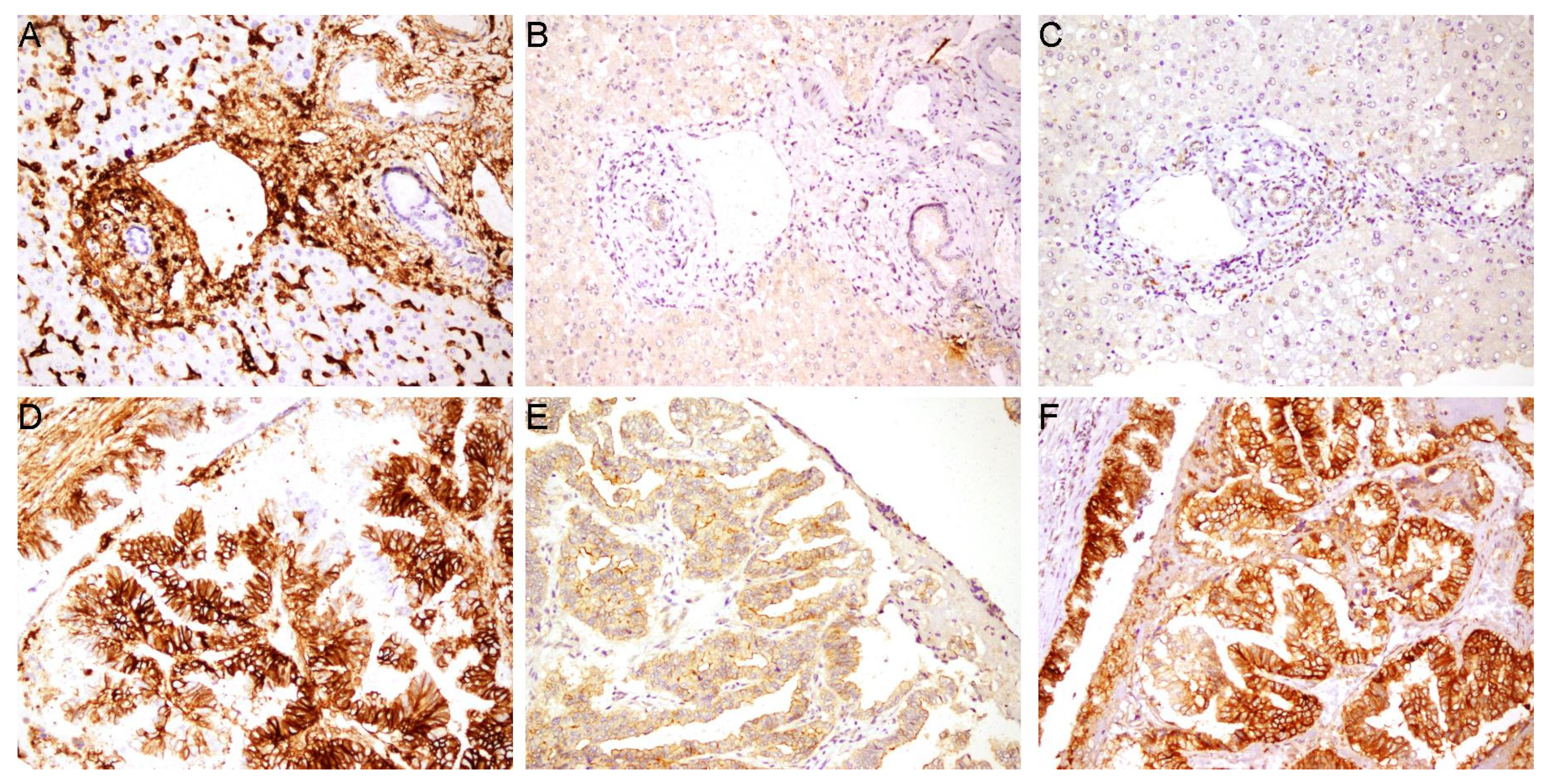

2.2. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

2.2.1. Tissue Preparation and Staining

2.2.2. IHC Scoring and Evaluation

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. AI-Assisted Manuscript Preparation

3. Results

3.1. Patient Cohort and CD44 Isoform Expression

3.2. Association of CD44 Isoform Expression with Clinicopathological Features

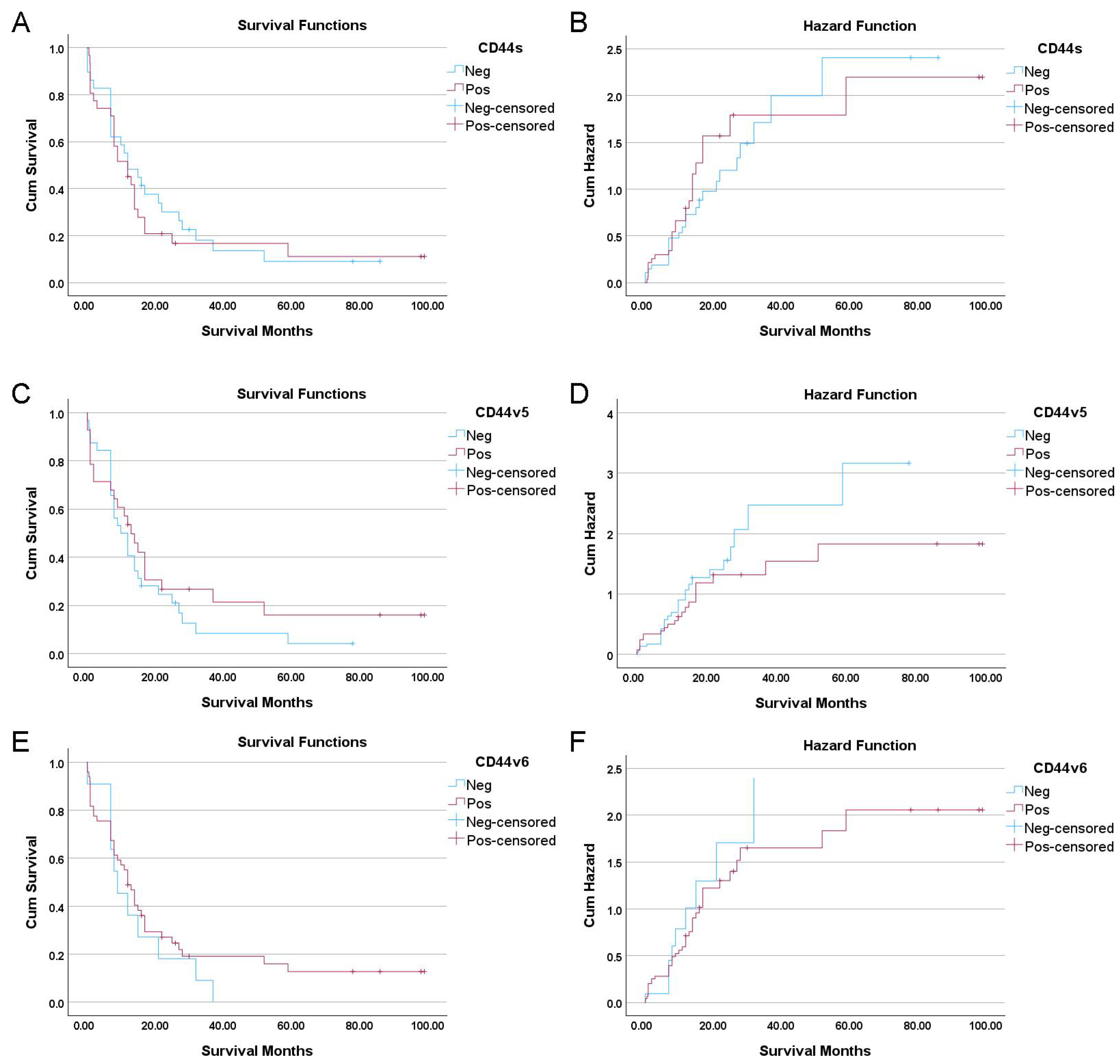

3.3. Univariate and Multivariate Survival Analyses

3.4. Association Among CD44 Isoform Expression

3.5. Multivariate Survival Analysis

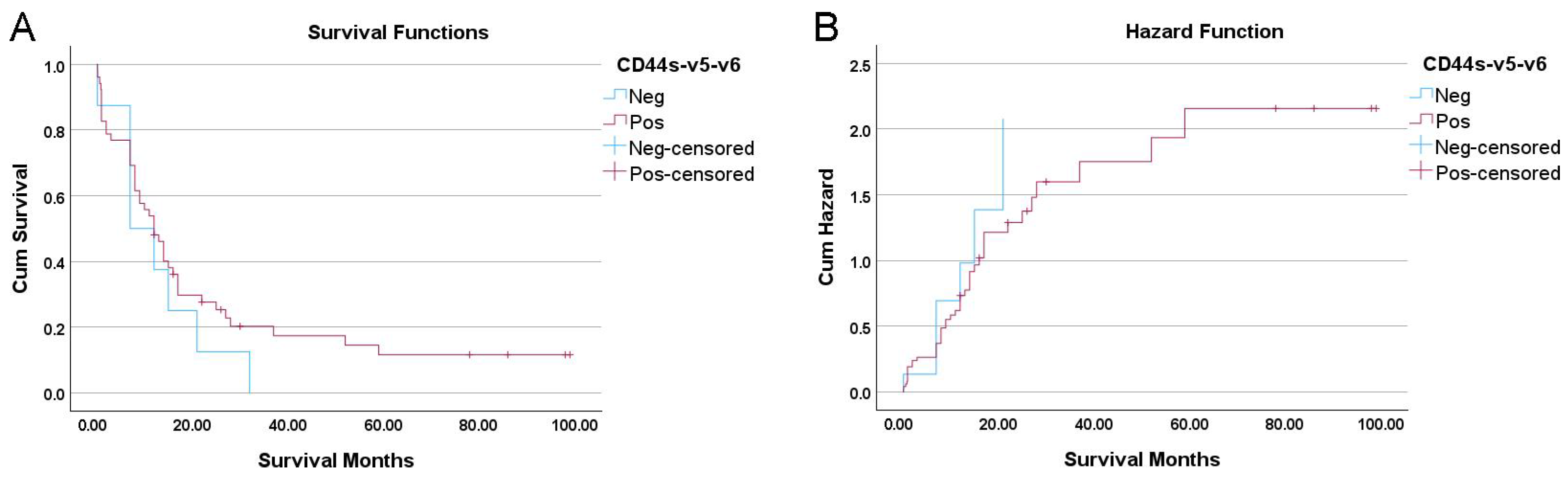

3.6. Prognostic Significance of a “CD44s-v5-v6 Null” Phenotype

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCA | Cholangiocarcinoma |

| CD44s | CD44 standard form |

| CD44v | CD44 variant isoforms |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| TNM | Tumor, Nodes, Metastasis (TNM staging) |

References

- Blechacz, B. Cholangiocarcinoma: Current Knowledge and New Developments. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeOliveira, M.L.; Cunningham, S.C.; Cameron, J.L.; Kamangar, F.; Winter, J.M.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Choti, M.A.; Yeo, C.J.; Schulick, R.D. Cholangiocarcinoma: Thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann. Surg. 2007, 245, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakeeb, A.; Pitt, H.A.; Sohn, T.A.; Coleman, J.; Abrams, R.A.; Piantadosi, S.; Hruban, R.H.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Yeo, C.J.; Cameron, J.L. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann. Surg. 1996, 224, 463–473; discussion 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Thomas, H.C.; Davidson, B.R.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet 2005, 366, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosconi, S.; Beretta, G.D.; Labianca, R.; Zampino, M.G.; Gatta, G.; Heinemann, V. Cholangiocarcinoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2009, 69, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banales, J.M.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Marzioni, M.; Andersen, J.B.; Invernizzi, P.; Lind, G.E.; Folseraas, T.; Forbes, S.J.; Fouassier, L.; et al. Expert consensus document: Cholangiocarcinoma: Current knowledge and future perspectives consensus statement from the European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma (ENS-CCA). Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treeprasertsuk, S.; Poovorawan, K.; Soonthornworasiri, N.; Chaiteerakij, R.; Thanapirom, K.; Mairiang, P.; Sawadpanich, K.; Sonsiri, K.; Mahachai, V.; Phaosawasdi, K. A significant cancer burden and high mortality of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Thailand: A nationwide database study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, T. Cholangiocarcinoma—Controversies and challenges. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 8, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner, A.; Vidili, G.; Rengo, M.; Bujanda, L.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Lamarca, A. Clinical presentation, diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banales, J.M.; Marin, J.J.G.; Lamarca, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Khan, S.A.; Roberts, L.R.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Andersen, J.B.; Braconi, C.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: The next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 557–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckmann, K.R.; Patel, D.K.; Landgraf, A.; Slade, J.H.; Lin, E.; Kaur, H.; Loyer, E.; Weatherly, J.M.; Javle, M. Chemotherapy outcomes for the treatment of unresectable intrahepatic and hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A retrospective analysis. Gastrointest. Cancer Res. 2011, 4, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, T.; Singh, P. Cholangiocarcinoma: Emerging approaches to a challenging cancer. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2007, 23, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Karnad, A.; Freeman, J. The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: Therapeutic implications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Xie, L.; Huang, A.; Xue, C.; Gu, Z.; Wang, K.; Zong, S. The Prognostic and Clinical Value of CD44 in Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesrati, M.H.; Syafruddin, S.; Mohtar, M.; Syahir, A. CD44: A Multifunctional Mediator of Cancer Progression. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, D.; Lu, T.-X.; Chang, S.W. Structural Characterization of the CD44 Stem Region for Standard and Cancer-Associated Isoforms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primeaux, M.; Gowrikumar, S.; Dhawan, P. Role of CD44 isoforms in epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity and metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2022, 39, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashida, K.; Terada, T.; Kitamura, Y.; Kaibara, N. Expression of E-cadherin, alpha-catenin, beta-catenin, and CD44 (standard and variant isoforms) in human cholangiocarcinoma: An immunohistochemical study. Hepatology 1998, 27, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padthaisong, S.; Thanee, M.; Namwat, N.; Phetcharaburanin, J.; Klanrit, P.; Khuntikeo, N.; Titapun, A.; Sungkhamanon, S.; Saya, H.; Loilome, W. Overexpression of a panel of cancer stem cell markers enhances the predictive capability of the progression and recurrence in the early stage cholangiocarcinoma. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, Q.; Pestell, R.; Wu, K. The role of CD44 in epithelial–mesenchymal transition and cancer development. OncoTargets Ther. 2015, 8, 3783–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Roudi, R.; Mirzaei, A.; Mirzaei, A.Z.; Madjd, Z.; Abolhasani, M. CD44 epithelial isoform inversely associates with invasive characteristics of colorectal cancer. Biomark. Med. 2019, 13, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klatte, T.; Seligson, D.B.; Rao, J.Y.; Yu, H.; de Martino, M.; Garraway, I.; Wong, S.G.; Belldegrun, A.S.; Pantuck, A.J. Absent CD44v6 expression is an independent predictor of poor urothelial bladder cancer outcome. J. Urol. 2010, 183, 2403–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipponen, P.; Aaltoma, S.; Kosma, V.-M.; Ala-Opas, M.; Eskelinen, M. Expression of CD44 standard and variant-v6 proteins in transitional cell bladder tumours and their relation to prognosis during a long-term follow-up. J. Pathol. 1998, 186, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, K.; Hackert, T.; Zöller, M. CD44/CD44v6 a Reliable Companion in Cancer-Initiating Cell Maintenance and Tumor Progression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | n (61) | CD44s | CD44v5 | CD44v6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neg | Pos | p-Value | Neg | Pos | p-Value | Neg | Pos | p-Value | ||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 38 | 20 | 18 | 0.306a | 20 | 18 | 0.972 a | 7 | 31 | 1.000 b |

| Female | 23 | 9 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 4 | 19 | |||

| Age (year) | ||||||||||

| ≤60 | 33 | 13 | 20 | 0.167 a | 14 | 19 | 0.088 a | 4 | 29 | 0.317 b |

| >60 | 28 | 16 | 12 | 18 | 10 | 7 | 21 | |||

| Macroscopic tumor growth | ||||||||||

| Mass forming type | 37 | 17 | 20 | 0.757 a | 20 | 17 | 0.757 a | 5 | 32 | 0.254 a |

| Intraductal type | 24 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 18 | |||

| Size | ||||||||||

| <5 cm | 21 | 10 | 11 | 0.640 a,Ψ | 13 | 8 | 0.200 a,Ψ | 5 | 16 | 0.579 a,Ψ |

| ≥5 cm | 34 | 14 | 20 | 15 | 19 | 6 | 28 | |||

| Location | ||||||||||

| Intrahepatic | 48 | 19 | 29 | 0.050 b,*,§ | 23 | 25 | 0.337 b,§ | 9 | 39 | 1.000 b,§ |

| Extrahepatic | 12 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 10 | |||

| Tumor focality | ||||||||||

| Solitary | 40 | 21 | 19 | 0.037 b,*,Ψ | 22 | 18 | 0.322 a,Ψ | 10 | 30 | 0.255 b,Ψ |

| Multiple | 15 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 14 | |||

| Histologic grade | ||||||||||

| Well differentiated | 36 | 21 | 15 | 0.005 c,* | 18 | 18 | 0.515 c | 7 | 29 | 0.634 c |

| Moderately differentiated | 16 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 13 | |||

| Poorly differentiated | 9 | 0 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 8 | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||||||

| Yes | 38 | 16 | 22 | 0.275 a | 21 | 17 | 0.573 a | 5 | 33 | 0.203 a |

| No | 23 | 13 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 6 | 17 | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||||||

| Yes | 33 | 15 | 18 | 0.723 a | 14 | 19 | 0.088 a | 4 | 29 | 0.317 b |

| No | 28 | 14 | 14 | 18 | 10 | 7 | 21 | |||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||||||

| Yes | 56 | 28 | 28 | 0.357 b | 30 | 26 | 0.662 b | 10 | 46 | 1.000 b |

| No | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Perineural invasion | ||||||||||

| Yes | 44 | 19 | 25 | 0.273 a | 21 | 23 | 0.234 a | 8 | 36 | 1.000 b |

| No | 17 | 10 | 7 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 14 | |||

| Resected margin | ||||||||||

| Free margin | 34 | 13 | 21 | 0.134 a,§ | 16 | 18 | 0.414 a,§ | 8 | 26 | 0.320 b,§ |

| Not free margin | 26 | 15 | 11 | 15 | 11 | 3 | 23 | |||

| TNM Staging | ||||||||||

| Stage I, II | 32 | 14 | 18 | 0.533 a | 14 | 18 | 0.152 a | 2 | 30 | 0.018 b,* |

| Stage III, IV | 29 | 15 | 14 | 18 | 11 | 9 | 20 | |||

| Variable | No. of Patients | Median OS (Months) | HR | (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| ≤60 years | 32 | 11 | 1 | 0.307 | |

| >60 years | 28 | 12 | 1.34 | (0.77–2.33) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 38 | 11 | 1 | 0.326 | |

| Female | 22 | 13 | 1.35 | (0.74–2.43) | |

| Tumor Location | |||||

| Intrahepatic | 47 | 12 | 1 | 0.940 § | |

| Extrahepatic | 12 | 10 | 1.026 | (0.523–2.01) | |

| Macroscopic Growth | |||||

| Intraductal | 23 | 22 | 1 | 0.006 * | |

| Mass forming | 37 | 8 | 2.3 | (1.27–4.17) | |

| Histology | <0.001 * | ||||

| Well differentiated | 35 | 15 | 1 | ||

| Mod vs. Well | 16 | 7 | 2.22 | (1.14–4.33) | 0.019 * |

| Poor vs. Well | 9 | 8 | 3.73 | (1.65–8.42) | 0.002 * |

| Tumor Size | |||||

| <5 cm | 21 | 14 | 1 | 0.046 Ψ,* | |

| ≥5 cm | 33 | 9 | 1.89 | (1.01–3.54) | |

| Tumor Focality | |||||

| Solitary | 40 | 13 | 1 | 0.064 Ψ,* | |

| Multiple | 14 | 3 | 1.9 | (0.96–3.73) | |

| Lymph Node Metastasis | |||||

| No | 32 | 14 | 1 | 0.031 * | |

| Yes | 28 | 8 | 1.87 | (1.06–3.30) | |

| Distant Metastasis | |||||

| No | 55 | 12 | 1 | 0.49 | |

| Yes | 5 | 8 | 1.39 | (0.55–3.51) | |

| Lymphovascular Invasion | |||||

| No | 37 | 14 | 1 | 0.154 | |

| Yes | 23 | 9 | 1.51 | (0.86–2.67) | |

| Resected Margin | |||||

| Free margin | 34 | 12 | 1 | 0.691 | |

| Not free margin | 25 | 11 | 1.12 | (0.64–1.98) | |

| Perineural Invasion | |||||

| No | 43 | 12 | 1 | 0.359 | |

| Yes | 17 | 12 | 1.33 | (0.72–2.46) | |

| TNM Stage | |||||

| I, II | 31 | 16 | 1 | 0.028 * | |

| III, IV | 29 | 8 | 1.88 | (1.07–3.28) | |

| CD44s Expression | |||||

| Negative | 29 | 12 | 1 | 0.630 | |

| Positive | 31 | 12 | 1.15 | (0.66–1.99) | |

| CD44v5 Expression | |||||

| Negative | 32 | 10 | 1 | 0.333 | |

| Positive | 28 | 13 | 0.76 | (0.43–1.33) | |

| CD44v6 Expression | |||||

| Negative | 11 | 9 | 1 | 0.386 | |

| Positive | 49 | 12 | 0.74 | (0.38–1.46) | |

| Isoform Pair | Phi (Φ) Coefficient | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| CD44s vs. CD44v5 | 0.117 | 0.359 |

| CD44s vs. CD44v6 | 0.322 | 0.012 * |

| CD44v5 vs. CD44v6 | 0.361 | 0.005 * |

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Clinical Model | |||

| Histology (Moderate vs. Well) | 1.883 | 0.819–4.328 | 0.136 |

| Histology (Poor vs. Well) | 3.468 | 1.273–9.450 | 0.015 * |

| TNM Stage (III/IV vs. I/II) | 0.993 | 0.399–2.473 | 0.988 |

| Lymph Node Metastasis (Yes vs. No) | 1.833 | 0.757–4.439 | 0.179 |

| Macroscopic Growth (Intraductal vs. Mass) | 0.874 | 0.365–2.094 | 0.763 |

| Tumor Size (≥5 cm vs. <5 cm) | 1.146 | 0.529–2.484 | 0.73 |

| Model + CD44s | |||

| Histology (Moderate vs. Well) | 2.051 | 0.864–4.871 | 0.104 |

| Histology (Poor vs. Well) | 4.345 | 1.315–14.359 | 0.016 * |

| TNM Stage (III/IV vs. I/II) | 0.918 | 0.356–2.365 | 0.859 |

| Lymph Node Metastasis (Yes vs. No) | 1.942 | 0.787–4.792 | 0.150 |

| Macroscopic Growth (Intraductal vs. Mass) | 0.899 | 0.378–2.138 | 0.809 |

| Tumor Size (≥5 cm vs. <5 cm) | 1.118 | 0.521–2.402 | 0.774 |

| CD44s (Positive vs. Negative) | 0.771 | 0.372–1.597 | 0.484 |

| Model + CD44v5 | |||

| Histology (Moderate vs. Well) | 1.945 | 0.850–4.451 | 0.115 |

| Histology (Poor vs. Well) | 3.355 | 1.226–9.180 | 0.018 * |

| TNM Stage (III/IV vs. I/II) | 1.09 | 0.422–2.812 | 0.859 |

| Lymph Node Metastasis (Yes vs. No) | 1.612 | 0.622–4.174 | 0.325 |

| Macroscopic Growth (Intraductal vs. Mass) | 0.902 | 0.378–2.150 | 0.816 |

| Tumor Size (≥5 cm vs. <5 cm) | 1.228 | 0.556–2.715 | 0.611 |

| CD44v5 (Positive vs. Negative) | 0.797 | 0.407–1.560 | 0.507 |

| Model + CD44v6 | |||

| Histology (Moderate vs. Well) | 1.967 | 0.847–4.565 | 0.115 |

| Histology (Poor vs. Well) | 3.887 | 1.373–11.001 | 0.011 * |

| TNM Stage (III/IV vs. I/II) | 0.86 | 0.336–2.199 | 0.752 |

| Lymph Node Metastasis (Yes vs. No) | 1.871 | 0.768–4.555 | 0.168 |

| Macroscopic Growth (Intraductal vs. Mass) | 0.817 | 0.331–2.021 | 0.662 |

| Tumor Size (≥5 cm vs. <5 cm) | 1.176 | 0.539–2.565 | 0.683 |

| CD44v6 (Positive vs. Negative) | 0.604 | 0.285–1.281 | 0.189 |

| Model + CD44s-v5-v6 | |||

| Histology (Moderate vs. Well) | 1.954 | 0.848–4.506 | 0.116 |

| Histology (Poor vs. Well) | 3.979 | 1.396–11.336 | 0.010 * |

| TNM Stage (III/IV vs. I/II) | 0.897 | 0.353–2.276 | 0.819 |

| Lymph Node Metastasis (Yes vs. No) | 1.756 | 0.716–4.307 | 0.219 |

| Macroscopic Growth (Intraductal vs. Mass) | 0.855 | 0.349–2.094 | 0.733 |

| Tumor Size (≥5 cm vs. <5 cm) | 1.193 | 0.547–2.602 | 0.657 |

| CD44s-v5-v6 (Positive vs. Negative) | 0.602 | 0.252–1.438 | 0.253 |

| Variable | n | CD44s-v5-v6 Null | CD44s-v5-v6+ | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 38 | 4 | 34 | 0.461 a |

| Female | 23 | 4 | 19 | |

| Age (year) | ||||

| ≤60 | 33 | 3 | 30 | 0.451 a |

| >60 | 28 | 5 | 23 | |

| Macroscopic Tumor Growth | ||||

| Mass forming type | 37 | 4 | 33 | 0.700 a |

| Intraductal type | 24 | 4 | 20 | |

| Size | ||||

| <5 cm | 21 | 4 | 17 | 0.464 a,Ψ |

| ≥5 cm | 34 | 4 | 30 | |

| Location | ||||

| Intrahepatic | 48 | 7 | 41 | 1.000 a,§ |

| Extrahepatic | 12 | 1 | 11 | |

| Tumor Focality | ||||

| Solitary | 40 | 7 | 33 | 0.423 a,Ψ |

| Multiple | 15 | 1 | 14 | |

| Histologic Grade | ||||

| Well differentiated | 36 | 5 | 31 | 0.402 b |

| Moderately differentiated | 16 | 3 | 13 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 9 | 0 | 9 | |

| Lymphovascular Invasion | ||||

| No | 38 | 4 | 34 | 0.461 a |

| Yes | 23 | 4 | 19 | |

| Lymph Node Metastasis | ||||

| No | 33 | 2 | 31 | 0.127 a |

| Yes | 28 | 6 | 22 | |

| Distant Metastasis | ||||

| No | 56 | 8 | 48 | 1.000 a |

| Yes | 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| Perineural Invasion | ||||

| No | 44 | 5 | 39 | 0.674 a |

| Yes | 17 | 3 | 14 | |

| Resected Margin | ||||

| Free margin | 34 | 6 | 28 | 0.446 a |

| Not free margin | 26 | 2 | 24 | |

| TNM Stage | ||||

| I/II | 32 | 1 | 31 | 0.022 a,* |

| III/IV | 29 | 7 | 22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Myint, K.Z.; Mongkonsiri, T.; Jinawath, A.; Tohtong, R. Association of a CD44s-v5-v6 Null Phenotype with Advanced Stage Cholangiocarcinoma: A Preliminary Study. Cancers 2026, 18, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010021

Myint KZ, Mongkonsiri T, Jinawath A, Tohtong R. Association of a CD44s-v5-v6 Null Phenotype with Advanced Stage Cholangiocarcinoma: A Preliminary Study. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleMyint, Kyaw Zwar, Thanakrit Mongkonsiri, Artit Jinawath, and Rutaiwan Tohtong. 2026. "Association of a CD44s-v5-v6 Null Phenotype with Advanced Stage Cholangiocarcinoma: A Preliminary Study" Cancers 18, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010021

APA StyleMyint, K. Z., Mongkonsiri, T., Jinawath, A., & Tohtong, R. (2026). Association of a CD44s-v5-v6 Null Phenotype with Advanced Stage Cholangiocarcinoma: A Preliminary Study. Cancers, 18(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010021