The Role of Computed Tomography-Determined Total Tumor Volume at Baseline in Predicting Outcomes of Patients with Locally Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

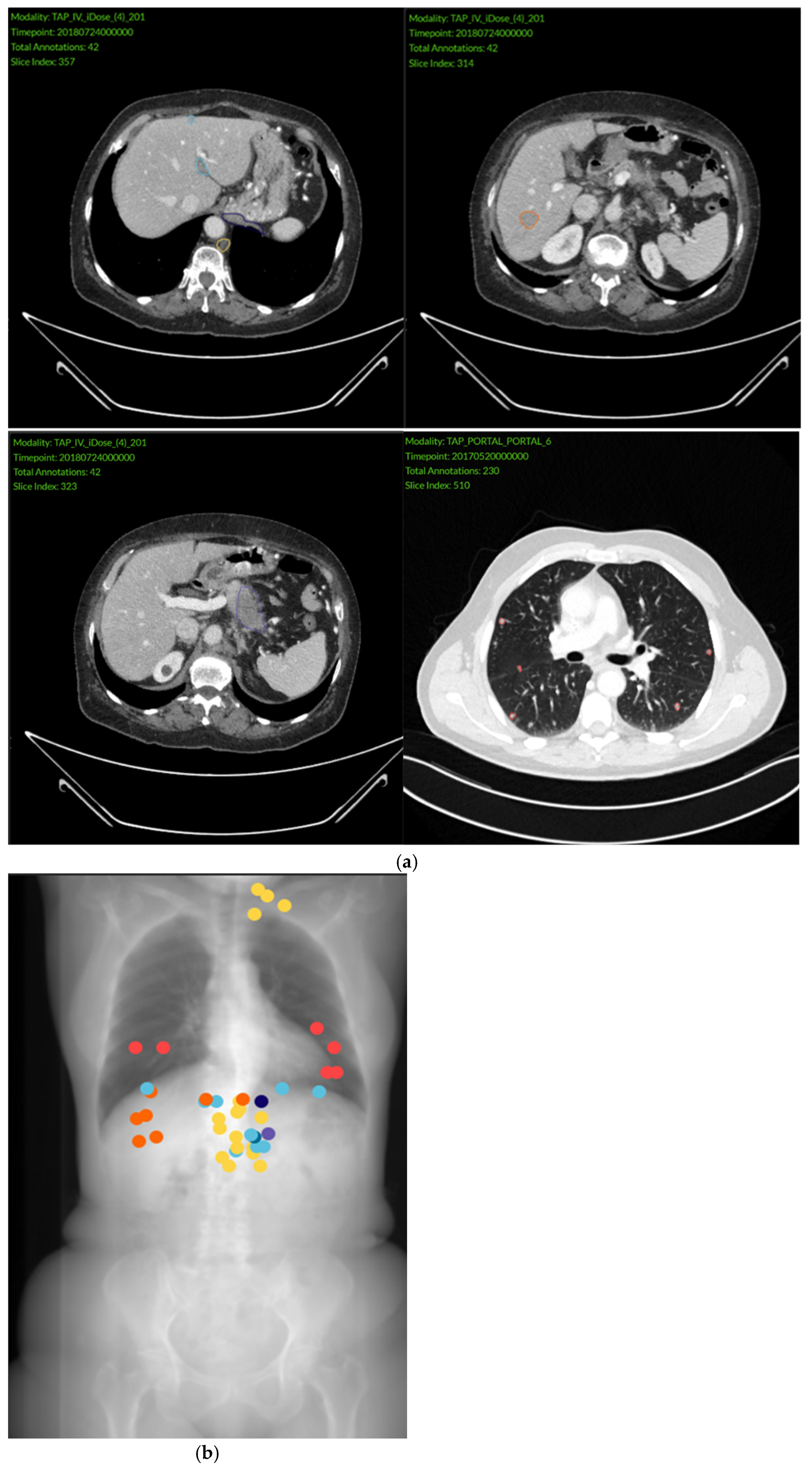

2.2. Imaging Analysis

2.3. Baseline Parameters and Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Descriptive Analysis

2.4.2. Predictive Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the General Population

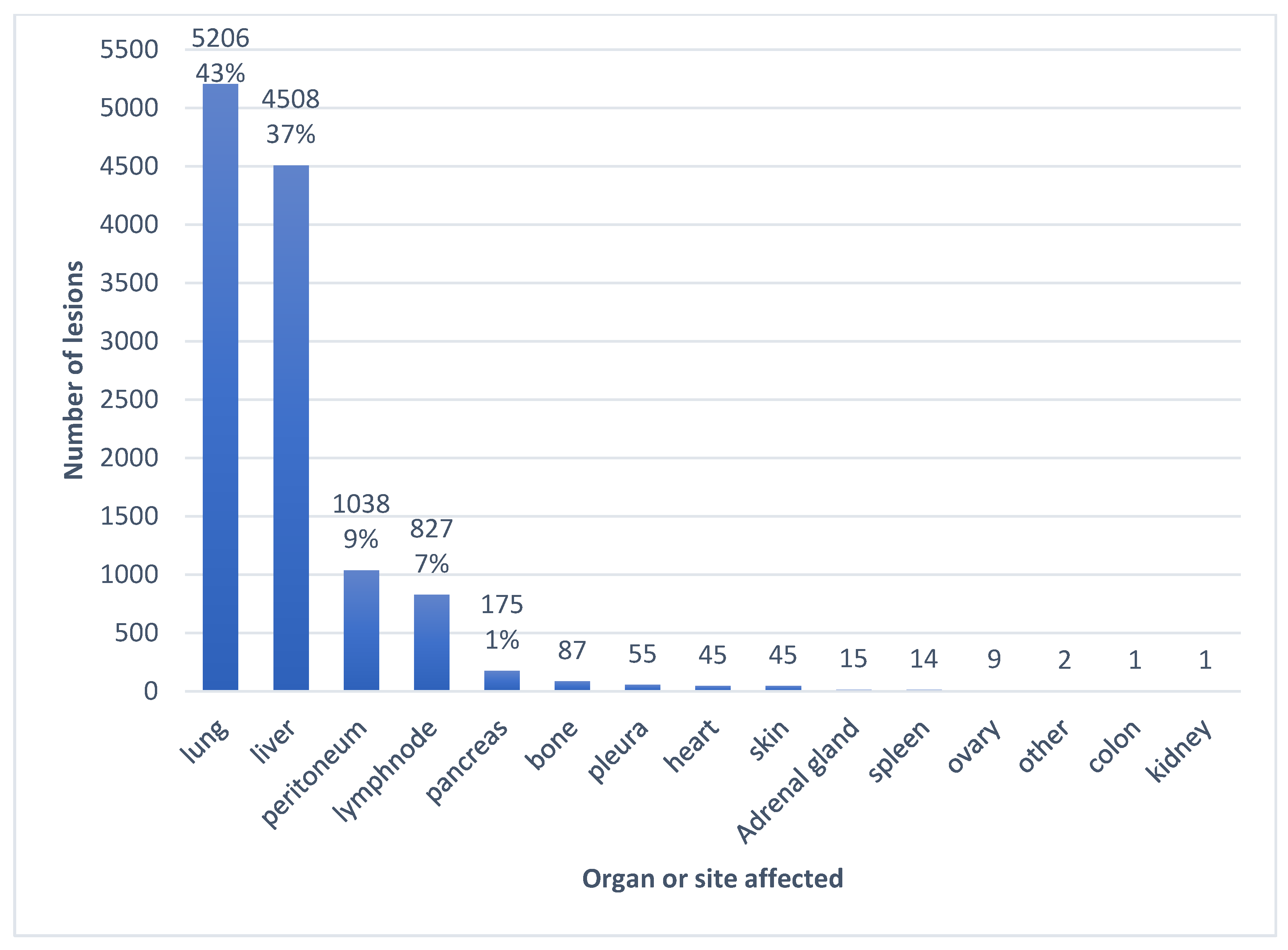

3.2. Imaging Findings

3.3. Patient Survival According to TTV

3.4. Correlation Between Baseline Parameters

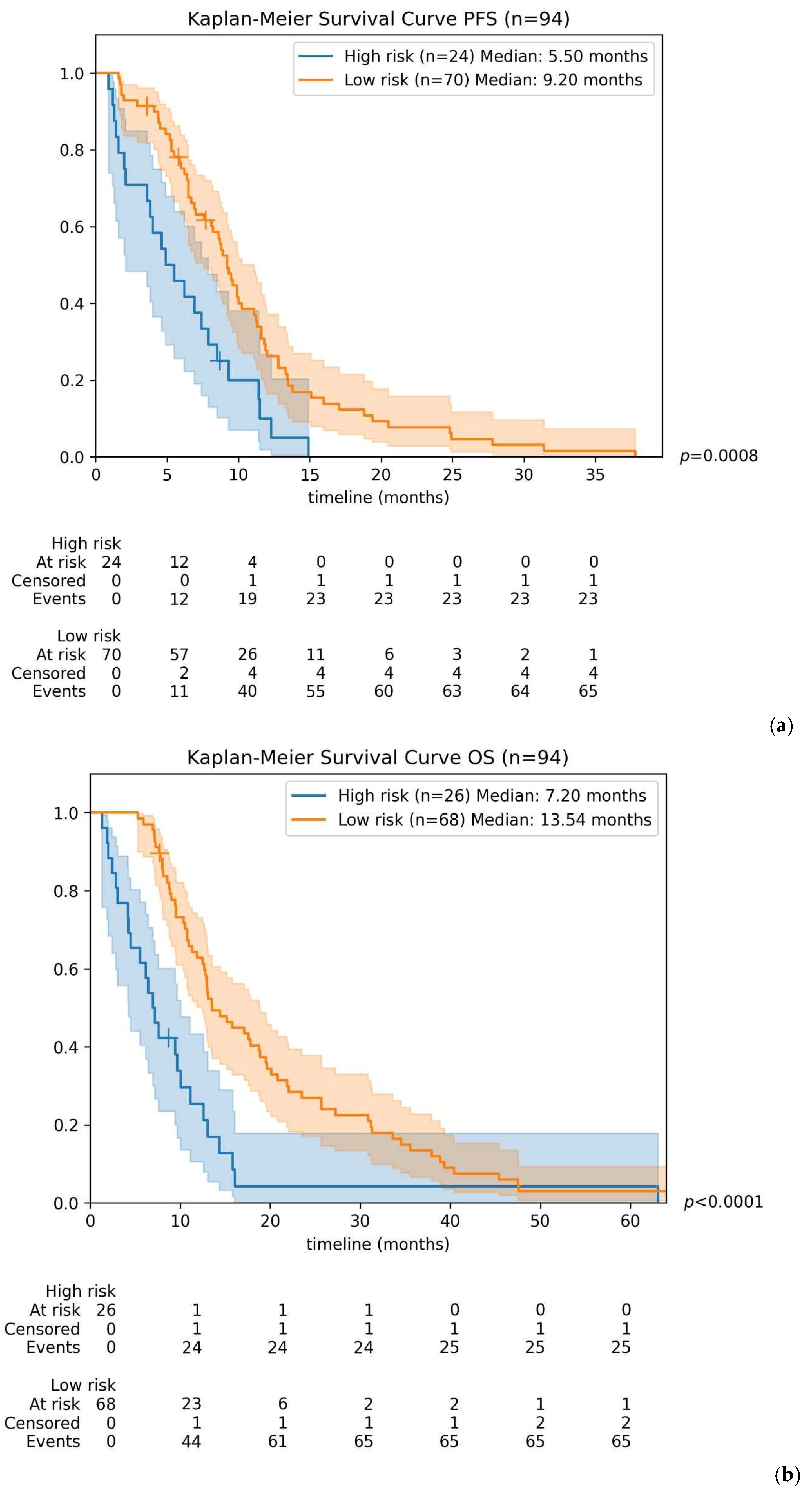

3.5. Survival Model According to a Combined Risk Score

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CA 19-9 | Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| INSEE | Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| MLR | Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PFS | Progression free survival |

| PLR | Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| RECIST | Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors |

| TTV | Total tumor volume |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramai, D.; Smith, E.R.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Obaitan, I.; Chandan, S.; Dhindsa, B.; Papaefthymiou, A.; Morris, J.D. Epidemiology and Socioeconomic Impact of Pancreatic Cancer: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2019. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2024, 69, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, T.; Desseigne, F.; Ychou, M.; Bouché, O.; Guimbaud, R.; Bécouarn, Y.; Adenis, A.; Raoul, J.-L.; Gourgou-Bourgade, S.; De La Fouchardière, C.; et al. FOLFIRINOX versus Gemcitabine for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hoff, D.D.; Ervin, T.; Arena, F.P.; Chiorean, E.G.; Infante, J.; Moore, M.; Seay, T.; Tjulandin, S.A.; Ma, W.W.; Saleh, M.N.; et al. Increased Survival in Pancreatic Cancer with nab-Paclitaxel plus Gemcitabine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, R.; Jiang, X.; Peng, Y.; Xu, H.; Yan, Y.; Liu, L.; Tang, X. A nomogram prediction of overall survival based on lymph node ratio, AJCC 8th staging system, and other factors for primary pancreatic cancer. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas, F.; Sen, F.; Odabas, H.; Kılıc, L.; Keskın, S.; Yıldız, I. Performance status of patients is the major prognostic factor at all stages of pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 18, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, E.D.; Machado, M.C.; Wajsbrot, D.; Abramoff, R.; Hoff, P.M.; Tabacof, J.; Katz, A.; Simon, S.D.; Gansl, R.C. Pretreatment CA 19-9 Level as a Prognostic Factor in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Treated with Gemcitabine. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2002, 32, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reni, M.; Cereda, S.; Balzano, G.; Passoni, P.; Rognone, A.; Fugazza, C.; Mazza, E.; Zerbi, A.; Di Carlo, V.; Villa, E. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 change during chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2009, 115, 2630–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, M.; Heinemann, V.; Kullmann, F.; Laubender, R.P.; Klose, C.; Bruns, C.J.; Holdenrieder, S.; Modest, D.P.; Schulz, C.; Boeck, S. Prognostic value of CA 19-9, CEA, CRP, LDH and bilirubin levels in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer: Results from a multicenter, pooled analysis of patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 139, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.-S.; Luo, H.-Y.; Qiu, M.-Z.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Zhang, D.-S.; Wang, F.-H.; Li, Y.-H.; Xu, R.-H. Comparison of the prognostic values of various inflammation based factors in patients with pancreatic cancer. Med. Oncol. 2012, 29, 3092–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas, F.; Aykan, F.; Alici, S.; Kaytan, E.; Aydiner, A.; Topuz, E. Prognostic Factors in Pancreatic Carcinoma. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 24, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wei, Q.; Fan, J.; Cheng, S.; Ding, W.; Hua, Z. Prognostic role of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis containing 8252 patients. Clin. Chim. Acta 2018, 479, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, N.; Okuda, T.; Sakagami, J.; Harada, T.; Ohara, T.; Taniguchi, M.; Sakai, H.; Oka, K.; Hara, T.; Tsuji, T.; et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts prognosis in unresectable pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.H.; Lee, J.; Park, S.H.; Lee, K.T.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, K.H.; Choi, D.W.; Choi, S.-H.; Heo, J.-S.; Lim, D.H.; et al. A Prognostic Model to Predict Clinical Outcomes with First-Line Gemcitabine-Based Chemotherapy in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Oncology 2011, 80, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, T.; Nakai, Y.; Yasunaga, H.; Isayama, H.; Matsui, H.; Takahara, N.; Sasaki, T.; Takagi, K.; Watanabe, T.; Yagioka, H.; et al. Prognostic nomogram for nonresectable pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine-based chemotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 1943–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutte, K.; Brulport, F.; Harguem-Zayani, S.; Schiratti, J.-B.; Ghermi, R.; Jehanno, P.; Jaeger, A.; Alamri, T.; Naccache, R.; Haddag-Miliani, L.; et al. An artificial intelligence model predicts the survival of solid tumour patients from imaging and clinical data. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 174, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.-X.; Zhao, H.; Bi, X.-Y.; Li, Z.-Y.; Huang, Z.; Han, Y.; Zhou, J.-G.; Zhao, J.-J.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Wei, W.-Q.; et al. Total tumor volume predicts survival following liver resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 9301–9310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, R.; Qiu, H.; Huang, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, G.; Li, D. Tumor Burden Score Stratifies Prognosis of Patients with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma After Hepatic Resection: A Retrospective, Multi-Institutional Study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 829407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkouchi, Y.; Nebot-Bral, L.; Lawrance, L.; Kind, M.; David, C.; Ammari, S.; Cournède, P.-H.; Talbot, H.; Vuagnat, P.; Smolenschi, C.; et al. Predicting immunotherapy outcomes in patients with MSI tumors using NLR and CT global tumor volume. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 982790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Kang, C.M.; Choi, H.J.; Lee, W.J.; Song, S.Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, J.D. Prognostic Value of Metabolic Tumor Volume and Total Lesion Glycolysis on Preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dholakia, A.S.; Chaudhry, M.; Leal, J.P.; Chang, D.T.; Raman, S.P.; Hacker-Prietz, A.; Su, Z.; Pai, J.; Oteiza, K.E.; Griffith, M.E.; et al. Baseline Metabolic Tumor Volume and Total Lesion Glycolysis Are Associated with Survival Outcomes in Patients with Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Receiving Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2014, 89, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, J.H.; Grieser, C.; Lehmkuhl, L.; Schnapauff, D.; Fernandez, C.P.; Maurer, M.H.; Mussler, A.; Hamm, B.; Denecke, T.; Steffen, I.G. Size determination and response assessment of liver metastases with computed tomography—Comparison of RECIST and volumetric algorithms. Eur. J. Radiol. 2013, 82, 1831–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, L.; Moltz, J.H.; Mühlberg, A.; Holch, J.W.; Huber, T.; Enke, J.; Jäger, N.; Haas, M.; Kruger, S.; Boeck, S.; et al. Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers of the Whole Liver Tumor Burden Improve Survival Prediction in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.M.; El-Rayes, B.F.; Li, X.; Hammad, N.; Philip, P.A.; Shields, A.F.; Zalupski, M.M.; Bekaii-Saab, T. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 is a prognostic and predictive biomarker in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who receive gemcitabine-containing chemotherapy: A pooled analysis of 6 prospective trials. Cancer 2012, 119, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, N.; Heilbrun, L.K.; A Philip, P.; Shields, A.F.; Zalupski, M.M.; Venkatramanamoorthy, R.; El-Rayes, B.F. CA19-9 as a predictor of tumor response and survival in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine based chemotherapy. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 6, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisey, N.R.; Norman, A.R.; Hill, A.; Massey, A.; Oates, J.; Cunningham, D. CA19-9 as a prognostic factor in inoperable pancreatic cancer: The implication for clinical trials. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 93, 740–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-J.; Hu, Z.-G.; Shi, W.-X.; Deng, T.; He, S.-Q.; Yuan, S.-G. Prognostic significance of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 2807–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-S.; Liu, W.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhong, A.; Meng, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z. Prognostic Predicting Role of Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography for Locally Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1356264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Lyu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, X.; He, Q. Ratio of CA19-9 Level to Total Tumor Volume as a Prognostic Predictor of Pancreatic Carcinoma After Curative Resection. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 21, 15330338221078438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanci, N.S.; Çelik, E.; Bagcilar, O.; Tutar, O.; Samanci, C.; Velidedeoglu, M.; Yassa, A.E.; Demirci, N.S.; Demirelli, F.H. Use of volumetric CT scanning to predict tumor staging and survival in pancreatic cancer patients that are to be administered curative resection. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 123, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, L.; Xu, K.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, T.; Hang, J.; Zee, B.C.-Y. Clinical significance of site-specific metastases in pancreatic cancer: A study based on both clinical trial and real-world data. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 1715–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y.; Lan, L.; Yang, S.; Drukker, K.; Morris, E.A.; Burnside, E.S.; Whitman, G.J.; Giger, M.L.; et al. Prediction of clinical phenotypes in invasive breast carcinomas from the integration of radiomics and genomics data. J. Med. Imaging 2015, 2, 041007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Velazquez, E.R.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Parmar, C.; Grossmann, P.; Carvalho, S.; Bussink, J.; Monshouwer, R.; Haibe-Kains, B.; Rietveld, D.; et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchweger, P.; Kupferthaler, A.; Burghofer, J.; Webersinke, G.; Jukic, E.; Schwendinger, S.; Weitzendorfer, M.; Petzer, A.; Függer, R.; Rumpold, H.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA correlates with tumor burden and predicts outcome in pancreatic cancer irrespective of tumor stage. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 48, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strijker, M.; Soer, E.C.; de Pastena, M.; Creemers, A.; Balduzzi, A.; Beagan, J.J.; Busch, O.R.; van Delden, O.M.; Halfwerk, H.; van Hooft, J.E.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA quantity is related to tumor volume and both predict survival in metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 146, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, M.; Virarkar, M.; Mahmoud, H.S.; Wong, V.K.; Baerga, C.I.G.; Parikh, M.; Elsherif, S.B.; Bhosale, P.R. Radiomics analysis with three-dimensional and two-dimensional segmentation to predict survival outcomes in pancreatic cancer. World J. Radiol. 2023, 15, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | N = 150 |

|---|---|

| Age (year) | |

| Median | 60 |

| IQR | 16 |

| Sex—n (%) | |

| Male | 78 (48%) |

| Female | 72 (52%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| Median | 24 |

| IQR | 5.7 |

| Alcohol consumption—n (%) | |

| Yes | 38 (25.4%) |

| No | 83 (55.3%) |

| NA | 29 (19.3%) |

| Smoking status—n (%) | |

| Smoker | 64 (42.7%) |

| Non-smoker | 60 (40%) |

| NA | 26 (17.3%) |

| ECOG Performance status score—n (%) | |

| 0 | 74 (49.3%) |

| 1 | 62 (41.4%) |

| 2 | 8 (5.3%) |

| 3 | 1 (0.7%) |

| NA | 5 (3.3%) |

| Pancreatic tumor location—n (%) | |

| Head | 44 (29.3%) |

| Uncus | 15 (10%) |

| Body | 4 (2.7%) |

| Isthmus | 27 (18%) |

| Tail | 31 (20.7%) |

| Multicentric | 29 (19.3%) |

| Characteristic | N = 150 |

|---|---|

| Ca 19-9—n (%) | |

| <37 U/L | 29 (19.3%) |

| 37–1000 U/L | 34 (22.7%) |

| ≥1000 U/L | 73 (48.7%) |

| NA | 14 (9.3%) |

| Median | 2064 |

| IQR | 7789 |

| CEA—n (%) | |

| <5 | 75 (50%) |

| ≥5 | 59 (39.3%) |

| NA | 16 (10.7%) |

| Median | 40.2 |

| IQR | 133.6 |

| Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio—n (%) | |

| <5 | 87 (58%) |

| ≥5 | 37 (24.7%) |

| NA | 26 (17.3%) |

| Median | 3.6 |

| IQR | 2.9 |

| Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio—n (%) | |

| <2 | 43 (28.7%) |

| ≥2 | 81 (54%) |

| NA | 26 (17.3%) |

| Median | 2.3 |

| IQR | 1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moujaes, E.; Dupont, J.; Lawrance, L.; Frau, F.; Jardali, G.; Dawi, L.; Kind, M.; Su, C.; Ammari, S.; Masri, N.; et al. The Role of Computed Tomography-Determined Total Tumor Volume at Baseline in Predicting Outcomes of Patients with Locally Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2026, 18, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010020

Moujaes E, Dupont J, Lawrance L, Frau F, Jardali G, Dawi L, Kind M, Su C, Ammari S, Masri N, et al. The Role of Computed Tomography-Determined Total Tumor Volume at Baseline in Predicting Outcomes of Patients with Locally Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoujaes, Elissar, Jules Dupont, Littisha Lawrance, Fiona Frau, Ghina Jardali, Lama Dawi, Michèle Kind, Caroline Su, Samy Ammari, Nohad Masri, and et al. 2026. "The Role of Computed Tomography-Determined Total Tumor Volume at Baseline in Predicting Outcomes of Patients with Locally Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma" Cancers 18, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010020

APA StyleMoujaes, E., Dupont, J., Lawrance, L., Frau, F., Jardali, G., Dawi, L., Kind, M., Su, C., Ammari, S., Masri, N., Mihele, A. B., Boige, V., Pudlarz, T., Smolenschi, C., Valéry, M., Camilleri, G. M., Boilève, A., Ducreux, M., Lassau, N., & Hollebecque, A. (2026). The Role of Computed Tomography-Determined Total Tumor Volume at Baseline in Predicting Outcomes of Patients with Locally Advanced Unresectable or Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers, 18(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010020