1. Introduction

The incidence of ovarian cancer has been steadily increasing globally over the past century [

1]. Epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) remains the leading cause of death from gynecologic malignancies in the US [

2]. Most of the patients are diagnosed at late metastatic stages and their chances of survival are low, largely due to the lack of effective anti-metastatic treatments. While the current standard of care, a combination of surgery and chemotherapy, is efficient as an initial treatment, in most cases EOC recurs after a few years, often becoming resistant to treatments, resulting in patient deaths [

2,

3]. The underlying causes of failure to prolong patient survival stem in part from an insufficient knowledge of basic biology and mechanisms supporting EOC metastasis and therapy resistance.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs or miRs) are a large class of non-coding RNAs that are about 22 nucleotides in length [

4]. They are transcribed by RNA polymerases (II and rarely III) to form primary miRNA transcript which is cleaved into pre-miRNA by the action of Drosha [

5]. The pre-miRNA is exported to the cytoplasm where it is cleaved by Dicer, and eventually forms the mature single-stranded miRNA [

5]. MiRNAs bind to messenger RNAs as part of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and serve as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression [

6]. They have been identified as key regulators of metastatic progression, tumor response to treatments, and clinical outcomes in EOC [

7,

8,

9]. The miR-200 family members are versatile and important players in EOC [

10]. Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas revealed that miR-141 and miR-200a, both members of the miR-200 family, are among eight miRNAs that were predicted to be master regulators of at least 89% targets in a miRNA regulatory network characteristic of the pro-malignant phenotype of serous EOC [

8].

The tumor microenvironment is complex and comprises cancer cells and stromal cells, the extracellular matrix in which they reside, and various signaling molecules secreted by all neighboring cells. The interactions between these components are mediated by different cell–cell, cell–matrix, and signal transduction communication mechanisms. A lesser-described mechanism of intercellular communication involves the cell–cell transfer of microRNAs [

11]. It has been reported that miRNAs can be transferred between multiple cell types, including tumor [

12]. These miRNAs can be transferred from cell to cell via secreted vesicles known as microvesicles and exosomes [

13]. Other modes of transfer, such as those via HDL particles and gap junctions, have been reported as well [

14,

15]. Multiple studies indicate that vesicles and miRNA found inside them play a role in supporting cancer progression, metastasis, and drug resistance [

16,

17,

18].

Malignant ascites is a unique feature of the EOC microenvironment [

19]. The ascites fluid is a rich source of growth factors, cytokines, and other signaling molecules, and it circulates around the abdomen, allowing delivery of its components to the peritoneal tissues and metastatic lesions that seed the peritoneum. Studies have identified exosomes in ascites of EOC patients [

20,

21]. Exosomes have been suggested to serve as potential messengers for the delivery of functional molecules to the cells [

22]. Exosomes from ovarian cancer patients were reported to contain miRNAs, and their delivery to the abdomen prior to the inoculation of tumor cells resulted in an increased tumor load in animal models [

23]. These data suggest that the functional transfer of exosomal components, including miRNA, may take place between cells, resulting in dramatic changes in the functional outcomes in the recipients. Such reprogramming of the cell fates in the recipient cells, both tumor and stromal, could result in the development of treatment resistance and aggressive metastatic phenotype among other potential outcomes. Specifically in ovarian cancer, several studies have focused on different types of vesicles (mainly exosomes) and their payloads [

24,

25,

26]. Given their ability to exert powerful effects on proliferation, migration, invasion, and drug resistance, it is understandable that there has been interest in studying the functional role of vesicular miRNA. It may, however, be crucial to expand beyond the functional implications alone. Every novel functional discovery makes it ever more compelling to study the mechanics of the process itself. Hence, we were interested in the characterization of miRNA transfer as a process of mediating intercellular communication. Given its relevance in the pathology of EOC, we selected miR-200a as the candidate to study functional miRNA transfer in EOC.

Several processes have been implicated for their role in the intercellular transfer of miRNAs in different cell models [

27]. These include, but are not limited to, gap junctions, apoptotic bodies, HDLs, and intercellular transfer of vesicles. In order to determine which process was largely contributing to intracellular miRNA transfer in the EOC cell lines, we used live-cell imaging with the dual-fluorophore model. We used a time-lapse live-cell fluorescence microscopy approach for constant monitoring of the cells in their typical cell culture environment to observe the mechanism of miRNA transfer. Further, we determined target gene expression in miRNA recipient cells and examined endocytic recycling pathways involved in the transport of transferred miRNA. Our study examines the mechanisms of functional miRNA transfer between cells, thus presenting a way of intercellular communication in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma.

2. Materials and Methods

Cell Lines: Human ovarian carcinoma cell lines of high-grade serous histotype Kuramochi and OVSAHO were obtained from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (Osaka, Japan). Human serous ovarian carcinoma cell lines SKOV-3 and OVCAR-4 were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Tumor Cell Repository (Detrick, MD, USA). A human high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma cell line, Caov-3, and human ovarian carcinoma cell line ES2 with features of high-grade serous histotype (TP53 mutation [

28]) were obtained from Dr. M. S. Stack (University of Notre Dame, IN, USA). Kuramochi, OVSAHO, SKOV-3, Caov-3, and ES2 were cultured according to the manufacturer’s instructions using minimal essential media (MEM) (Corning; Tewksbury, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (SIGMA-ALDRICH; St.Louis, MO, USA), 0.5% penicillin/streptomycin (Corning), 0.4% amphotericin B (Corning), and 0.22% g/mL sodium bicarbonate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Dallas, TX, USA) for less than 20 consecutive passages. OVCAR-4 was grown in RPMI (Corning) containing 10% FBS, 0.5% penicillin/streptomycin, 0.4% amphotericin B, and 0.2% g/mL sodium bicarbonate. All cells were kept at 37 °C and 5% CO

2 in a humidified incubator and were routinely tested for Mycoplasma. Cell line authentication was performed for all the cell lines using the STR analysis.

Materials. Mirus Label IT® miRNA Labeling kit and mirVana™ miRNA Mimic, negative control #1 (Cat No 4464058), and collagenase type I were obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Human collagen type I, rat tail collagen type I, and Matrigel were obtained from Corning. Poly-D-lysine was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH, USA). pEGFP-N1 plasmid was obtained from Clontech Laboratories (San Jose, CA, USA). ProlongGold was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Trizol was obtained from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Universal cDNA Synthesis kit and ExiLENT SYBR® Green master mix were purchased from Exiqon (Germantown, MD, USA). hsa-mir-200a miExpress™ Precursor miRNA Expression Clone, (Product ID: HmiR0002, precursor sequence: ccgggccccugugagcaucuuaccggacagugcuggauuucccagcuugacucuaacacugucugguaacgauguucaaaggugacccgc) and EndoFectin™ Max Transfection Reagent were obtained from Genecopoeia (Rockville, MD, USA). SV Total RNA isolation system was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). High-capacity reverse transcription kit and SYBR green were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Waltham, MA, USA). Anti-human EEA1 antibody was from Life Technologies (Waltham, MA, USA), and anti-human-RAB4, -RAB5, -RAB7, -RAB9, and -RAB11 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA, USA). Goat anti-mouse-FITC and goat anti-rabbit -Alexa488 antibodies were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Newark, CA, USA). DharmaFECT was from GE Dharmacon (Marlborough, MA, USA).

miRNA labeling. Mirus Label IT® miRNA Labeling kit was used to covalently label miRNA mimics with fluorescent tags (either Cy3, used in the imaging experiments, or Cy5, used in the flow cytometry measurements) using the manufacturer’s recommended protocol.

Transfection of GFP plasmid with EndoFectin™ Max: The cell lines were transfected with pEGFP-N1 plasmid using the EndoFectin™ Max Transfection Reagent to generate the recipient GFP-positive cell populations for the dual-fluorophore model. The manufacturer’s recommended transfection protocol was utilized.

Transfection of labeled miRNAs: The transfection reagent DharmaFECT was used to transiently transfect the labeled miRNAs into the donor cell populations using the manufacturer’s recommended protocol.

In vitro dual-fluorophore model to study miRNA transfer using fluorescence microscopy: Donor cells transfected with fluorescently (Cy3) labeled miRNA mimics were co-cultured with recipient cells tagged with GFP on glass coverslips at 50% confluency. Following 24 h, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL for 15 min. Cells were washed, air-dried, and mounted on glass slides using ProlongGold. Fluorescence imaging of mounted cells was performed using a Zeiss AxioObserverD.1 fluorescence microscope (Jena, Germany).

Live-cell Imaging microscopy of cells cultured using dual-fluorophore model: Donor cells transfected with fluorescently (Cy3) labeled miRNA mimics were co-cultured with recipient cells tagged with GFP on poly-D-lysine coated MattekTM glass 35 mm plates at 50% confluency. The cells were imaged using the Olympus Viva View FL Incubator Microscope (Center Valley, PA, USA). Images were acquired in the green, red, and DIC channels every 10 min for 24 h over multiple z-stacks. The acquired images were collapsed and processed using the Metamorph image analysis software (Molecular Devices; San Jose, CA, USA).

In vivo model to study miRNA transfer using multiphoton microscopy: 1.5 × 106 donor cells transfected with fluorescently (Cy3) labelled miRNA mimics were mixed with 1.5 × 106 recipient cells tagged with GFP and injected intraperitoneally into athymic nude mice (n = 3). After 48 h, the mice were euthanized. The peritoneal wall was excised, and multiphoton imaging was performed using the Prairie Technologies Ultima In Vivo Multiphoton Microscopy System. The 3D and orthogonal reconstruction were performed using the Imaris viewer (Oxford Instruments; Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK).

Coating of cell culture plates with different modified supports: Tissue culture-treated plates were pre-coated with 10 μg/mL human collagen type I, Matrigel (1:100 dilution), or 0.5 mg/mL Poly-D-Lysine for 1 h at 37 °C. The plates were rinsed with PBS and air-dried before use.

Ovarian cancer spheroid models: The ovarian cancer spheroids were generated by culturing the cells on plates using an agarose overlay method, as described previously [

29,

30]. The overlay was prepared by pouring 0.5% agarose on the culture plates and then allowing it to solidify and cool at room temperature for at least 30 min prior to adding a suspension of ovarian cancer cells.

Flow cytometric quantification of miRNA transfer frequency: Donor cells transfected with fluorescently (Cy5) labeled miRNA mimics were co-cultured with recipient cells tagged with GFP. After 24 h, the cells were trypsinized, washed, and resuspended in PBS, and then analyzed by using the BD Acuri C6 flow cytometer (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The number of GFP-positive recipient cells that were also positive for the Cy3 miRNA were measured as a percentage of the total number of GFP-positive recipient cells in order to determine the frequency of the miRNA transfer process.

Measurement of miR-200a expression levels: miRNA-200a expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR. The miRNA isolation was performed by lysing 1 × 10

6 cells in 1 mL of Trizol and precipitating with isopropanol and chloroform. Reverse transcription was performed using Universal cDNA Synthesis kit (Roche; Indianapolis, IN, USA) according to the recommended protocol. ExiLENT SYBR

® Green master mix was used to perform qPCR for miRNA 200a (Exiqon LNA primer 204539) normalized to controls. UniSp6 and miR-103 were used as normalization controls. Data were analyzed using the 2

−∆∆Ct method and Student’s

t-test, as described previously [

31,

32].

Transfection of miRNA Expression plasmids: The ES-2 cell line was transfected with hsa-mir-200a miExpress™ Precursor miRNA Expression Clone using the EndoFectin™ Max Transfection Reagent to generate the GFP-positive miRNA-200a over-expressing cells, termed ES2-miR200OE. The manufacturer’s recommended transfection protocol was utilized.

miRNA-200a transfer experimental setup: The donor cells with high miR-200a expression were co-cultured with recipient cells that expressed little or no miR-200a for 48 h. The donor and recipient cell populations were distinguished by tagging one of the populations with GFP. Using the GFP label, cells were sorted out using the Moflo cell sorter (UIC Flow Cytometry core facility) and the recipient cells were collected for further analysis by qRT-PCR.

Measurement of miR-200a target gene expression levels: Total RNA isolation was performed with the SV Total RNA isolation system using manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription was performed using the high-capacity reverse transcription kit, according to the recommended protocol. Q-PCR was performed using SYBR green for ZEB1, ZEB2, CTNNB1, and TGFβ2 (all predicted gene targets of miR-200a). The primer sequences are as follows:

ZEB1

Forward Primer: TTACACCTTTGCATACAGAACCC

Reverse Primer: TTTACGATTACACCCAGACTGC

ZEB2

Forward Primer: AATGCACAGAGTGTGGCAAGGC

Reverse Primer: CTGCTGATGTGCGAACTGTAGG

CTNNB1

Forward Primer: CATCTACACAGTTTGATGCTGCT

Reverse Primer: GCAGTTTTGTCAGTTCAGGGA

TGFβ2

Forward Primer CCATCCCGCCCACTTTCTAC

Reverse Primer AGCTCAATCCGTTGTTCAGGC

RPL19 and

EEF1A1 were used as housekeeping gene controls. Data were analyzed using the 2

−∆∆Ct method and Student’s

t-test, as described previously [

31,

32].

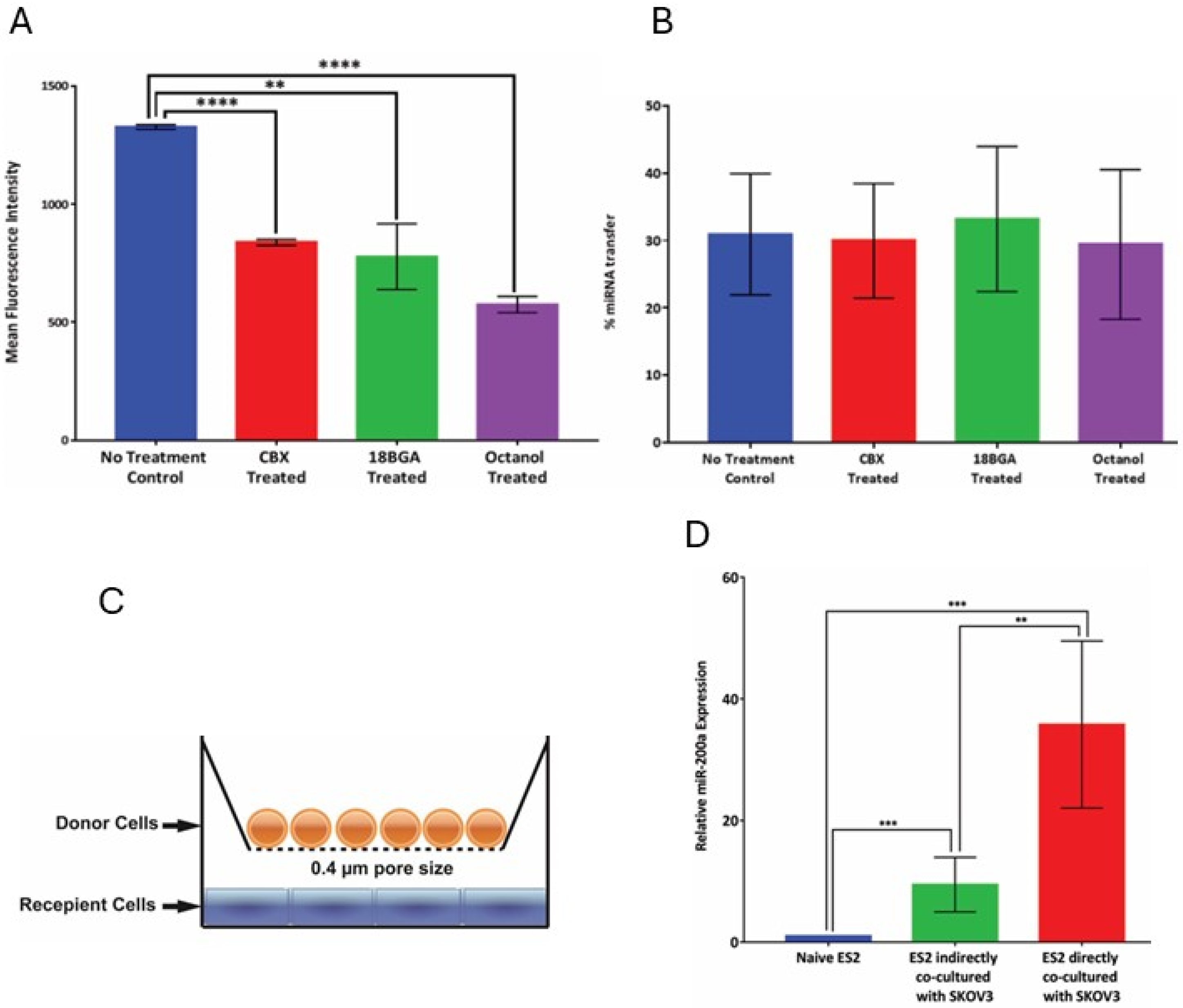

Gap junction inhibition and scrape-loading dye transfer assay: 18 Beta glycyrrhetinic acid (18-BGA), carbeneoxonolone (CBX), and 1-octanol were used as biochemical inhibitors of gap junction activity. The cells were treated with the inhibitors (at 50 μM concentrations) in serum-free conditions. Inhibition of gap junction activity was tested using the scrape-loading dye transfer assay. For this assay, the cells were grown in complete monolayers. Following overnight treatment with the inhibitors, the cells were rinsed trice with PBS, and a 0.5 mg/mL solution of Lucifer Yellow was added to the cells. Scrapes were made in the monolayer using a scalpel blade and the plates were left undisturbed, in the dark for 3 min. Cells are then washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The extent of the permeation of the Lucifer Yellow dye from the scrape line into the adjacent cell monolayer was observed by using the Zeiss AxioObserverD.1 fluorescence microscope. The mean fluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ (

https://imagej.net/ij/; date of access 12 December 2015).

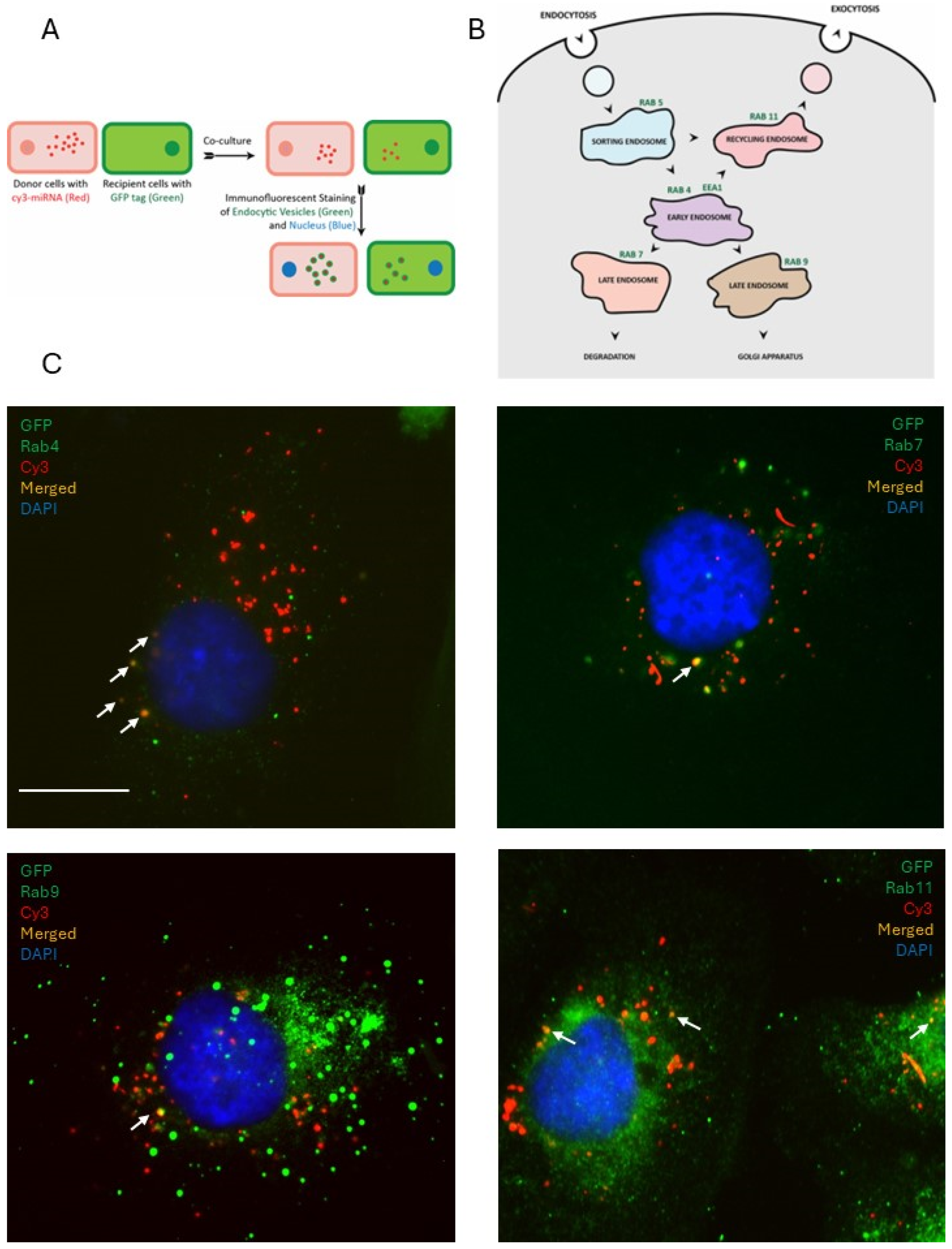

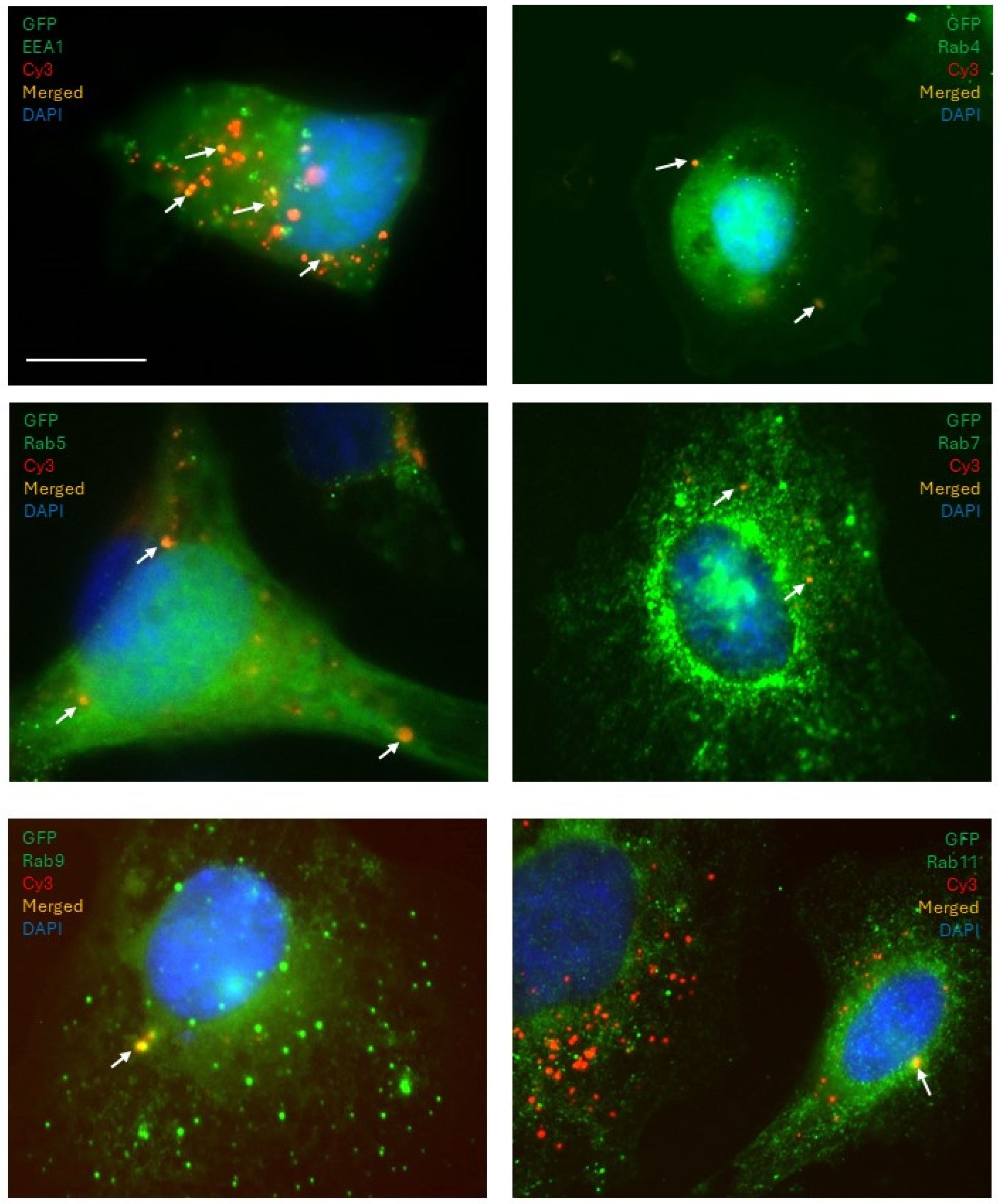

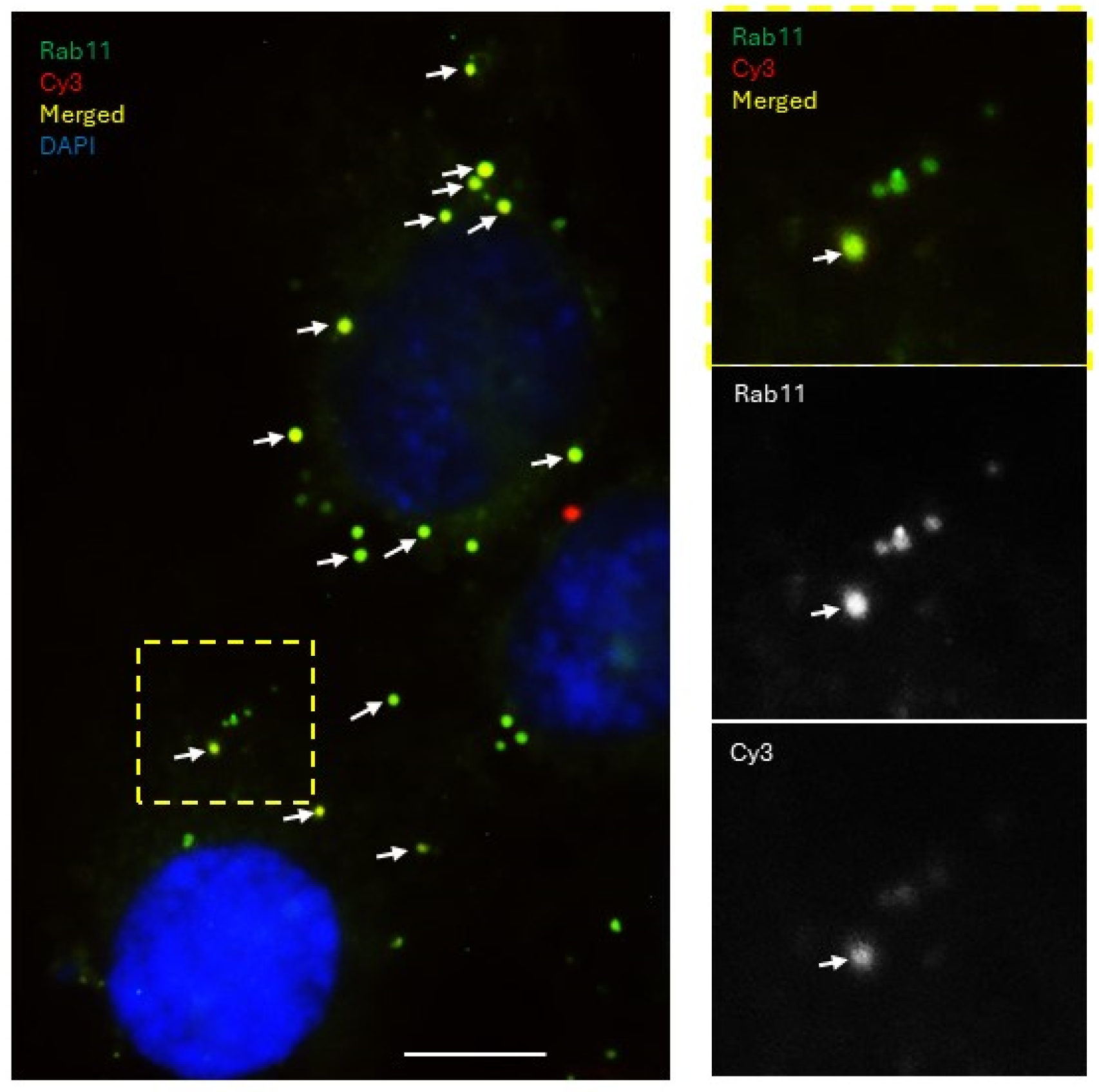

Immunofluorescence microscopy: Donor cells transfected with fluorescently (Cy3) labeled miRNA mimics were co-cultured with recipient cells tagged with GFP on glass coverslips at 50% confluency. Following 24 h, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X-100. Primary antibodies for EEA1 (Life Technologies), RAB4, RAB5, RAB7, RAB9, and RAB11 (Cell Signaling) were used to immunostain for the early, sorting, and late endosomes at a dilution of 1:500 and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibodies goat anti-mouse-FITC (for EEA1) and goat anti-rabbit-Alexa488 (for the Rab family) were incubated with the cells at a dilution of 1:1000 for 1 h at RT. Cells were incubated with 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL for 15 min, washed, air-dried, and mounted on glass slides using Prolong Gold (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Fluorescence imaging was performed using a Zeiss AxioObserverD.1 fluorescence microscope.

4. Discussion

The concept of miRNAs acting as mobile signaling molecules is appealing due to their versatility and ability to exert powerful control over the regulation of gene expression. Our findings demonstrate the existence of miRNA transfer between cells in models of serous ovarian carcinoma and indicate the importance of vesicular transport in this process.

Importantly, our results suggest that the transferred miRNA was functional in affecting the target gene expression in the recipient cells. Epithelial ovarian cancer is known for its heterogeneity in gene expression. In light of our findings, this may indicate that a message in the form of miRNA can easily spread between the neighboring cells in the tumor and its microenvironment and affect target gene expression, thus regulating and contributing to tumor cell heterogeneity. Hence, the relevance of this mode of intracellular communication in this particular malignancy could be very high. Importantly, we observed that miR transfer occurred across different cell culture conditions in which multiple parameters were varied, including plating density, adherent or suspension culture, and materials used as culture supports. This suggested that this mode of intercellular communication could be quite common. Of note, our experimental setup did not include the possibility of quantifying transfer events between the donor cells; in reality, the percentage of miR recipient cells may be higher, if the latter events were also accounted for.

Our data also indicate that not only the neighboring cells but also those located at a distance from one another can send and receive miRs affecting gene expression in the recipient cell population. It is well established that most ovarian cancer patients develop large volumes of malignant ascites that are also an independent marker of worse outcomes [

36,

37]. In applying this observation to the situation in vivo, the specifics of the disease pathology suggest that the importance of miR transfer between distant cells in metastatic ovarian cancer can be very high, particularly because the miR-containing vesicles from the donor cells can easily reach many recipient cells by traveling via ascitic fluid that circulates throughout the abdomen.

Cell lines, primary cultures, multicellular aggregates (for example, mammospheres in breast cancer research and spheroids in ovarian cancer research), tissue explants, and organoids are a mainstay of basic studies of basic biological processes, such as mechanisms of cancer progression and therapy resistance. Our findings may also have direct implications for studies involving cells in culture. Any changes in gene expression due to the up- or down-regulation of expression of a gene of interest, or due to the effects of drugs, may bring about changes in miR gene expression, which may then be transferred to other cells. Even non-proliferating cells may be indirectly affected by drugs through transferred miRs released from cells destroyed by cytotoxic chemotherapy. Depending on the nature of the transferred miR and the target genes it affects, different mechanisms may be up- or down-regulated, resulting in divergent fates in the recipients. Additionally, we found that the efficiency of miR transfer in cells cultured on poly-D-lysine-coated supports and three-dimensional collagen type I gel was lower than those cultured on plastic supports, supports coated with collagen type I or Matrigel, or as three-dimensional spheroids. As poly-D-lysine is often used as a substrate for cell attachment to glass slides for various imaging applications, it is interesting to speculate that the same process that is reliant on miR transfer may be a cause of different experimental results if the gene expression is studied using different cell culture conditions. We have previously described that ovarian cancer cells adopt a pro-metastatic mesenchymal cell morphology when cultured on three-dimensional collagen type I gel [

38,

39]. This cell type, as opposed to epithelial, does not make extensive cell–cell connections, found to support miR transfer in our experiments. Hence, more research is needed to better understand how changes from epithelial to mesenchymal type may contribute to the cell’s ability to uptake miRNA.

It is interesting to contemplate that the process of miR transfer may be a contributing factor resulting in progression to a more aggressive metastatic phenotype. A recent study found that all miR-200 family miRNAs are overexpressed in the extracellular fraction of the ascitic fluid of HGSOC patients [

40]. Thus, miR-200a represented a very attractive candidate for our study, not only due to its consistent involvement in ovarian cancer, but also because of its role in the process of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [

10,

41,

42]. Due to the involvement of the miR-200 family in the EMT transition, the functional transfer of miR-200a could be involved in cell transformation at the secondary tumor sites following metastasis. A double negative feedback loop between miR-200 and the ZEB genes taken into account along with the functional transfer of the microRNA could help us further understand the reversible nature of the EMT process. Intriguingly, attempts to profile miR-200 family expression in EOC [

10] produced discordant results, which, to an extent, could be explained by susceptibility to dynamic changes depending on the stage of tumor progression, EMT, localization of interacting proteins to the nucleus or cytoplasm, and cellular ROS content. Functional transfer of miR-200a would add complexity to the mechanisms controlling the fluctuations of its expression and might help in further understanding the variability observed in the profiling studies. Increased levels of miR-200a as well as a decrease in mRNA levels of the target genes provided a phenotypic read-out that coincided with the increased miRNA expression in recipient cells that initially expressed little or no endogenous miR-200a. The conclusion that this increase is due to miRNA transfer is supported by the fact that it was observed consistently over both a natural as well as an artificial gradient in miR-200a expression. The experimental setup with heterotypic cell lines addressed potential cell culture artifacts associated with artificially over-expressing miRNAs to study the process of transfer and demonstrated transfer of miR-200a from SKOV-3 to both ES2 and Kuramochi cell lines. However, more studies are needed to examine whether other miRNAs can also be transferred between cells using the natural gradient, and whether this transfer elicits changes in target gene expression in recipient cells. Importantly, changes in protein levels of the target genes need to be examined along with other functional outcomes, such as the introduction of chemoresistance, changes in cell morphology and EMT, and other processes associated with an increase in disease aggressiveness.

The use of time-lapse fluorescence confocal imaging was very instrumental in visualizing how the transfer of miR can occur between the donor and recipient cells. Intriguingly, two major modes of transfer were observed. In one mode of miR transfer, donor and recipient cells were observed to form cell–cell connections prior to the transfer occurring. It is likely that this mode of transfer may predominate between cells that adopted epithelial morphology. In another mode of miR transfer, dynamically migrating cells on the surface not attached to other cells were observed to pick up and internalize particles containing fluorescently labeled miRs; these particles may have come from multiple routes, such as nontransfected liposomes left over after donor cell transfection, vesicles shed from donor cells, or vesicles and apoptotic bodies left after donor cell death. It is possible that the cells that have undergone mesenchymal transition may favor this mode of miR transfer that is more closely related to endocytic uptake. The first mode of transfer has suggested at least two mechanistic routes of transfer, involving either gap junctions or extracellular vesicles, or both. Using biochemical inhibitors, we found that the contribution of the gap junction channels was insubstantial. However, it is possible that other mechanisms may become activated to compensate for the lack of gap junction activity. The partial restriction of vesicular transport by setting a passage limit to particles under 0.4 μm resulted in a two-fold reduction in the number of miRNA transfer events. However, the transfer still occurred, suggesting that vesicles of multiple sizes both below and above 0.4 μm may be involved in the process. Our study did not focus on detailed description of all possible types of extracellular vesicles that could be involved in this process, and more extensive studies are needed to better describe the types of vesicles that participate in the miR transfer process. It is important to point out that our experimental setup may introduce selection bias, as the liposomal transfection of large amounts of miRNA may preferentially turn on the process of purging the cargo out of the cells, and, in doing so, generate a much larger scale of the transfer. Although this bias was partially addressed with experiments utilizing the natural gradient of miR transfer, more studies of miR transfer involving natural gradients and multiple types of miRs are needed to uncover the scope of the phenomenon. Additionally, yet unknown confounding variables may have their contribution to the outcomes of our study. We attempted to partially eliminate their contribution by using several cell culture models; however, other cancerous and non-cancerous cell models need to be included in the future studies to obtain more generalizable data.

Imaging experiments to examine the colocalization of the labeled miRNAs with the endosomal markers presented evidence that the miRNAs are, at least partially, shuttled by endocytic trafficking. The sorting and the early endosomes, characterized by the surface presentation of proteins RAB5 (sorting), RAB4, and EEA1 (early), shuttle their contents towards one of three possible fates: (a) degradation in lysosomes through RAB7 late endosomes, (b) to the Golgi apparatus through RAB9 late endosomes, or (c) for extracellular release through RAB11 recycling endosomes. In the donor cells, they were observed packaged into the Rab5-positive sorting endosomes, which then progress into the Rab4/EEA1-positive early endosomes, then maturing into the Rab7/9-positive later endosomes, which were also observed in our experiments. A fraction of the miRNA population was found to colocalize with Rab11-positive vesicles, which can then be released by the cell through exocytosis. These secreted vesicles could then be internalized by the recipient cell and re-enter the endocytic pathway of the recipient cells, thus enabling them to spread the message between cells. Interestingly, we found that the patterns of colocalization of miRNAs with endosomal compartments differed between the non-functional control miRNA and the functional miR-200a mimic. Most of the signal associated with the functional miR-200a mimic colocalized with the Rab11-positive staining, suggesting that miR-200a was predominantly contained within recycling endosomes and was queued up for extracellular release. This presented a scenario in which the distribution pattern through the different endocytic pathways could change depending on whether the miRNA is functional or not. This may suggest that the cells could possess mechanisms that allow them to read and identify a miRNA sequence. This could imply that if the cell receives a message, it is capable of interpreting it and then decide either to act on it (i.e., change the target gene expression), or to ignore it and/or pass it along to another cell. If miRNAs are indeed involved in such a sophisticated system of communication, then the implication would be that the miRNA transfer process is not merely a passive event where the cell discards excess miRNAs into its surroundings where it can be passively absorbed by other cells. It could very well be an active process where a cell intentionally releases certain miRNA-mediated cues which the recipient cells can internalize, process, and decide on how to respond to. This does not exclude the possibility of a “passive” miRNA transfer in addition to or instead of the “active” one. However, if the active transfer does occur, it may indicate the existence of a sophisticated machinery that allows precise communication between an ovarian cancer cell and its microenvironment mediated by miRNAs. Future studies focusing on the examination of how different miRNAs trafficked through the endosomal pathways may help to understand whether such a complicated interaction network exists. Other mechanisms supporting intracellular trafficking, involving exocytosis, endocytosis, and autophagy, need to be examined in the context of miR transfer as well.

There has been considerable interest in using miRNA profiles as clinical biomarkers of various pathologies [

43,

44,

45]. The findings that miRs can transfer between cells may indicate that miR contents in cells could change dynamically based on many factors, which may complicate the use of miRNAs as diagnostic or prognostic markers of the disease progression and therapy response. It is likely that miR contents at any given time in any given cell population reflect just a single pattern in a dynamically changing profile. In future miR profiling studies and gene expression profiling studies, it would be interesting to examine whether miR contents and gene expression change in the same cell population at different time points, as functional transfer of miRNAs could potentially complicate their utility as consistent clinical biomarkers.