Population-Level Trends in Lifestyle Factors and Early-Onset Breast, Colorectal, and Uterine Cancers

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Average Annual Percent Change by Disease Site

3.3. Race/Ethnicity Analysis

3.4. Modifiable Lifestyle Risk Factors

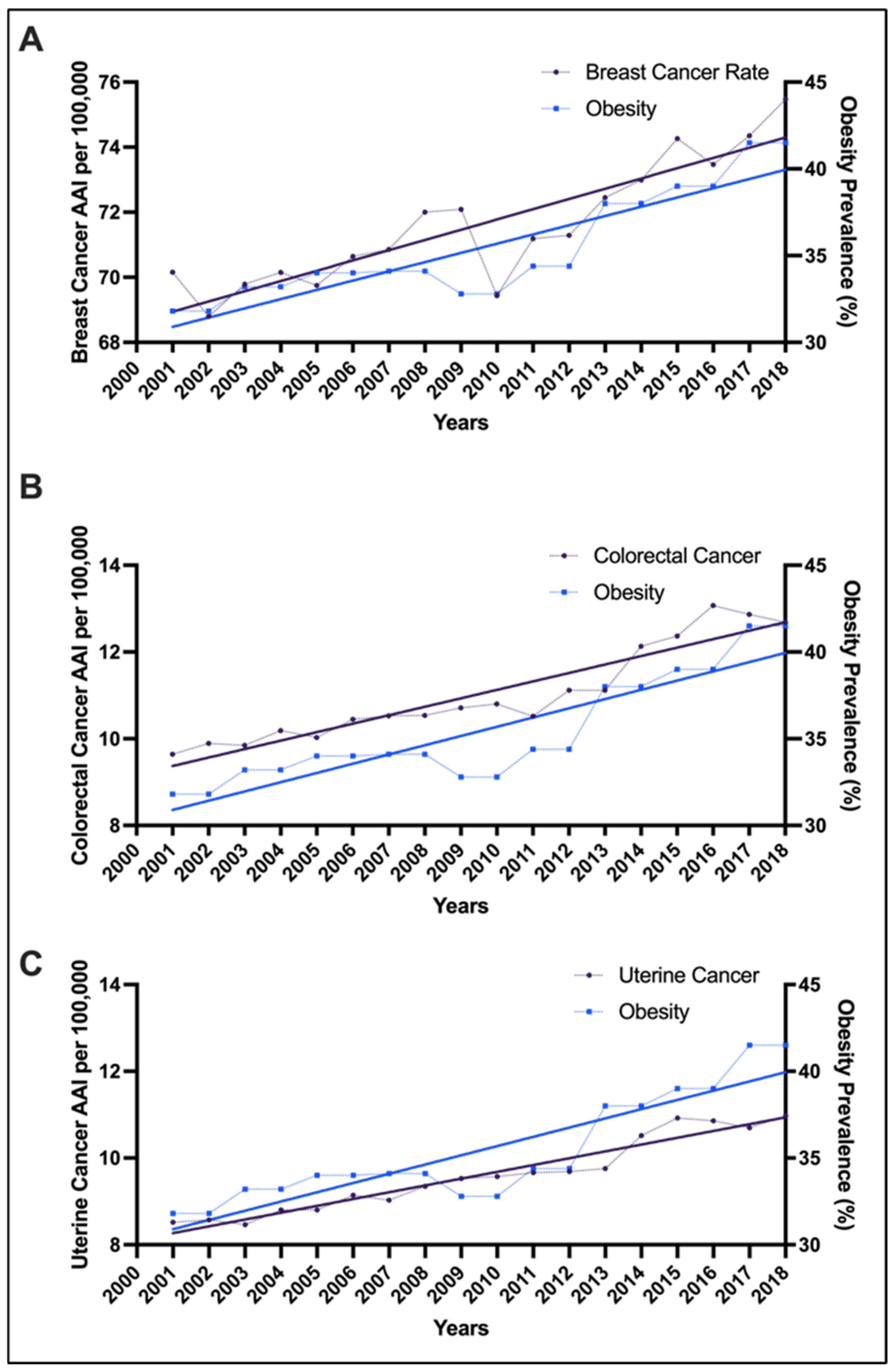

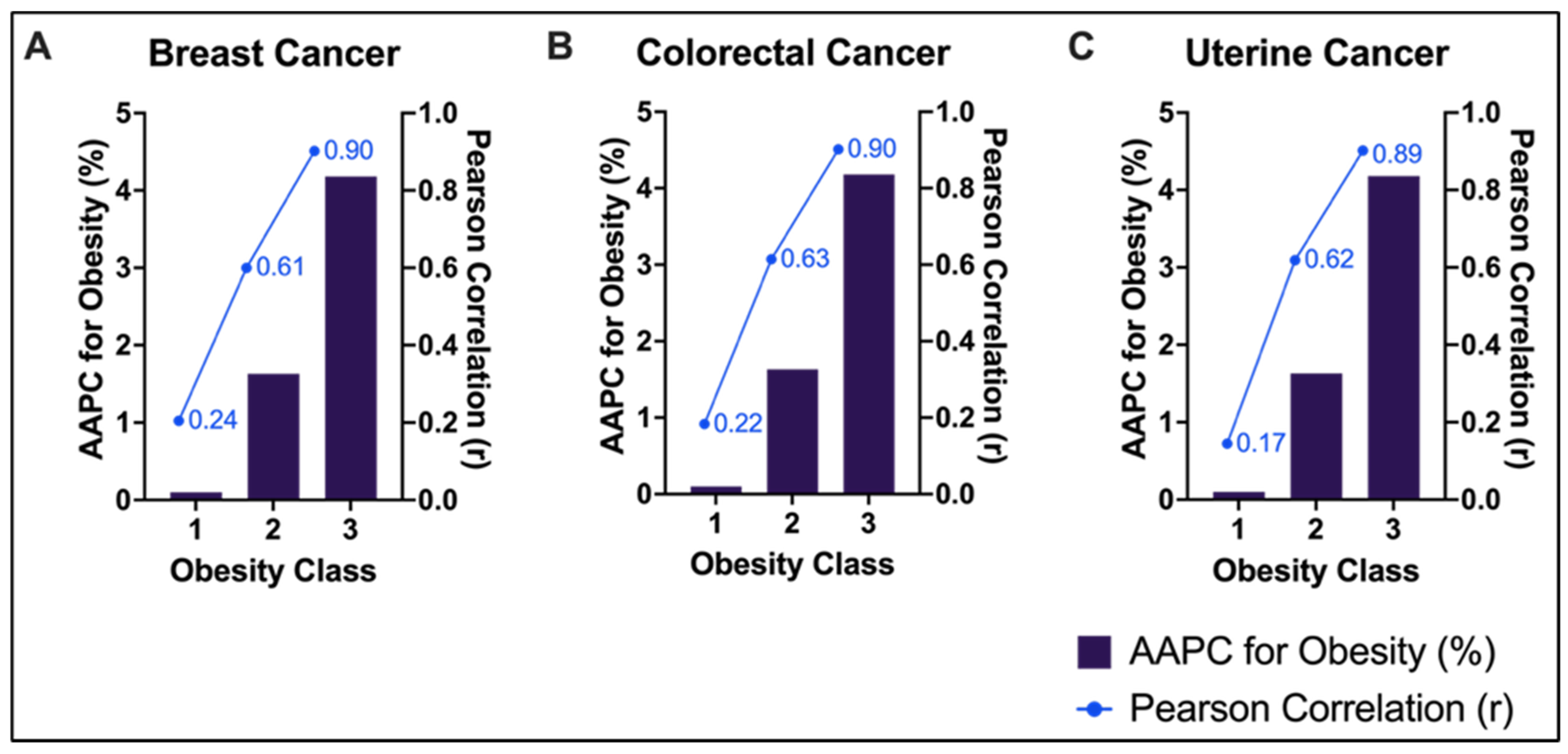

3.5. Obesity and Cancer Incidence Correlation

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary

4.2. Rising Early-Onset Cancer Rates

4.3. Lifestyle Factors Beyond Obesity

4.4. Future Directions

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Newman, L.A.; Freedman, R.A.; Smith, R.A.; Star, J.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast cancer statistics 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movsisyan, A.S.; Maguire, F.B.; Parikh-Patel, A.; Gholami, S.; Keegan, T.H. Increasing Rates of Colorectal Cancer Among Young People in California, 1988–2017. J. Regist. Manag. 2021, 48, 152. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.; Levine, L.; Berenson, A. Trends in the Incidence of Endometrial Cancer Among Young Women in the United States, 2001 to 2017; Wolters Kluwer Health: Waltham, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Francoeur, A.A.; Liao, C.-I.; Chang, J.; Johnson, C.R.; Clair, K.; Tewari, K.S.; Kapp, D.S.; Chan, J.K.; Bristow, R.E. Associated Trends in Obesity and Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer in the United States. Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 145, e107–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, B.E.; Casagrande, J.T.; Pike, M.C.; Mack, T.; Rosario, I.; Duke, A. The epidemiology of endometrial cancer in young women. Br. J. Cancer 1983, 47, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, D.K.; Boland, C.R.; Dominitz, J.A.; Giardiello, F.M.; Johnson, D.A.; Kaltenbach, T.; Levin, T.R.; Lieberman, D.; Robertson, D.J. Colorectal cancer screening: Recommendations for physicians and patients from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Murtagh, S.; Han, Y.; Wan, F.; Toriola, A.T. Breast cancer incidence among US women aged 20 to 49 years by race, stage, and hormone receptor status. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2353331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauby-Secretan, B.; Scoccianti, C.; Loomis, D.; Grosse, Y.; Bianchini, F.; Straif, K. Body fatness and cancer—Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renehan, A.G.; Tyson, M.; Egger, M.; Heller, R.F.; Zwahlen, M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 2008, 371, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avgerinos, K.I.; Spyrou, N.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Dalamaga, M. Obesity and cancer risk: Emerging biological mechanisms and perspectives. Metabolism 2019, 92, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Jiang, L.; Stefanick, M.L.; Johnson, K.C.; Lane, D.S.; LeBlanc, E.S.; Prentice, R.; Rohan, T.E.; Snively, B.M.; Vitolins, M.; et al. Duration of Adulthood Overweight, Obesity, and Cancer Risk in the Women’s Health Initiative: A Longitudinal Study from the United States. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Cancer Statistics Public Use Database. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/united-states-cancer-statistics/public-use/?CDC_AAref_Val5https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/public-use/index.htm (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES Questionnaires, Datasets, and Related Documentation. 2023. Available online: https://cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 BRFSS Survey Data and Documentation. Available online: https://cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2021.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fedewa, S.A.; Ahnen, D.J.; Meester, R.G.; Barzi, A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, V.; Quinn, M.A. Endometrial cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012, 26, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugai, T.; Sasamoto, N.; Lee, H.-Y.; Ando, M.; Song, M.; Tamimi, R.M.; Kawachi, I.; Campbell, P.T.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Weiderpass, E. Is early-onset cancer an emerging global epidemic? Current evidence and future implications. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 656–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiels, M.S.; Haque, A.T.; Berrington de González, A.; Camargo, M.C.; Clarke, M.A.; Davis Lynn, B.C.; Engels, E.A.; Freedman, N.D.; Gierach, G.L.; Hofmann, J.N. Trends in Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates in Early-Onset and Older-Onset Age Groups in the United States, 2010–2019. Cancer Discov. 2025, 15, 1363–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, E.E.; Rodriguez, C.; Walker-Thurmond, K.; Thun, M.J. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copson, E.; Cutress, R.; Maishman, T.; Eccles, B.K.; Gerty, S.; Stanton, L.; Altman, D.; Durcan, L.; Wong, C.; Simmonds, P. Obesity and the outcome of young breast cancer patients in the UK: The POSH study. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-H.; Wu, K.; Ng, K.; Zauber, A.G.; Nguyen, L.H.; Song, M.; He, X.; Fuchs, C.S.; Ogino, S.; Willett, W.C. Association of obesity with risk of early-onset colorectal cancer among women. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onstad, M.A.; Schmandt, R.E.; Lu, K.H. Addressing the role of obesity in endometrial cancer risk, prevention, and treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4225–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, L.M.; Wilson, R.J.; Ajani, U.A.; Singh, S.D.; Eheman, C.R. Trends in endometrial cancer incidence rates in the United States, 1999–2006. J. Women’s Health 2011, 20, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, M.L.; Patel, A.V.; Patel, R.; Rodriguez, C.; Feigelson, H.S.; Bandera, E.V.; Gansler, T.; Thun, M.J.; Calle, E.E. Body mass and endometrial cancer risk by hormone replacement therapy and cancer subtype. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2008, 17, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smrz, S.A.; Calo, C.; Fisher, J.L.; Salani, R. An ecological evaluation of the increasing incidence of endometrial cancer and the obesity epidemic. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 224, 506.e1–506.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucenik, I.; Stains, J.P. Obesity and cancer risk: Evidence, mechanisms, and recommendations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1271, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, E.J.; LeRoith, D. Obesity and diabetes: The increased risk of cancer and cancer-related mortality. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andò, S.; Gelsomino, L.; Panza, S.; Giordano, C.; Bonofiglio, D.; Barone, I.; Catalano, S. Obesity, Leptin and Breast Cancer: Epidemiological Evidence and Proposed Mechanisms. Cancers 2019, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, S.; Vargas, R.; Reizes, O. The impact of obesity and adipokines on breast and gynecologic malignancies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2022, 1518, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.M.; Brown, K.A.; Iyengar, N.M. Targeting obesity-related dysfunction in hormonally driven cancers. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Lopez, L.A.; Elizalde-Mendez, A. How far should we go in optimal cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer? Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, D.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, W. Association of habitual sleep duration and its trajectory with the risk of cancer according to sex and body mass index in a population-based cohort. Cancer 2023, 129, 3582–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lempesis, I.G.; Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Papalexis, P.; Chrousos, G.P.; Spandidos, D.A. Role of stress in the pathogenesis of cancer (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2023, 63, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, L.K.; Sobush, K.; Keener, D.; Goodman, K.; Lowry, A.; Kakietek, J.; Zaro, S. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2009, 58, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnardi, V.; Rota, M.; Botteri, E.; Tramacere, I.; Islami, F.; Fedirko, V.; Scotti, L.; Jenab, M.; Turati, F.; Pasquali, E.; et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: A comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botteri, E.; Borroni, E.; Sloan, E.K.; Bagnardi, V.; Bosetti, C.; Peveri, G.; Santucci, C.; Specchia, C.; van den Brandt, P.; Gallus, S.; et al. Smoking and Colorectal Cancer Risk, Overall and by Molecular Subtypes: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 1940–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolin, K.Y.; Yan, Y.; Colditz, G.A.; Lee, I.M. Physical activity and colon cancer prevention: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumgay, H.; Shield, K.; Charvat, H.; Ferrari, P.; Sornpaisarn, B.; Obot, I.; Islami, F.; Lemmens, V.E.P.P.; Rehm, J.; Soerjomataram, I. Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.; Gathani, T. Understanding breast cancer as a global health concern. Br. J. Radiol. 2022, 95, 20211033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Racial Group | Age Group | Breast AAPC for Cancer Incidence (95% CI); p-Value | Colorectal AAPC for Cancer Incidence (95% CI); p-Value | Uterine AAPC for Cancer Incidence (95% CI); p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | All (20–49) | 0.44 (0.3, 0.6); <0.001 | 1.75 (1.4, 2.1); <0.001 | 1.64 (1.4, 1.9); <0.001 |

| 20–24 | 1.69 (1.0, 2.4); <0.001 | 6.92 (4.3, 9.6); <0.001 | 2.74 (1.0, 4.6); =0.002 | |

| 25–29 | 1.62 (1.20, 2.1); <0.001 | 4.15 (3.2, 5.2); <0.001 | 3.25 (2.4, 4.1); <0.001 | |

| 30–34 | 0.69 (0.30, 1.1); =0.003 | 2.95 (2.2, 3.7); <0.001 | 2.92 (2.5, 3.4); <0.001 | |

| 35–39 | 0.20 (0.0, 0.4); 0.03 | 2.3 (1.9, 2.7); <0.001 | 2.8 (2.4, 3.2); <0.001 | |

| 40–44 | 0.51 (0.30, 0.7); <0.001 | 1.67 (1.4, 2.0); <0.001 | 1.91 (1.4, 2.5); <0.001 | |

| 45–49 | 0.42 (0.3, 0.6); <0.001 | 0.98 (0.6, 1.3); <0.001 | 0.78 (0.5, 1.1); <0.001 | |

| White | All (20–49) | 0.62 (0.5, 0.8); <0.001 | 2.27 (1.8, 2.8); <0.001 | - |

| 20–24 | 1.99 (1.0, 2.9); <0.001 | 7.97 (4.6, 11.4); <0.001 | - | |

| 25–29 | 2.02 (1.3, 2.8); <0.001 | 4.39 (3.0, 5.8); <0.001 | 2.49 (1.7, 3.3); <0.001 | |

| 30–34 | 0.83 (0.4, 1.3); <0.001 | 3.12 (2.4, 3.9); <0.001 | 1.8 (1.1, 2.5); <0.001 | |

| 35–39 | 0.34 (0.2, 0.5); =0.001 | 2.86 (2.1, 3.6); <0.001 | 2.2 (1.7, 2.8); <0.001 | |

| 40–44 | 0.71 (0.5, 0.9); <0.001 | 2.26 (1.8, 2.7); <0.001 | 1.42 (0.9, 2.0); <0.001 | |

| 45–49 | 0.6 (0.4, 0.7); <0.001 | 1.48 (0.9, 2.0); <0.001 | 0.42 (0.2, 0.6); <0.001 | |

| Black | All (20–49) | 0.31 (0.1, 0.5); =0.001 | - | - |

| 20–24 | 1.45 (−0.3, 3.3); 0.11 | - | - | |

| 25–29 | 0.54 (−0.2, 1.3); 0.17 | - | 2.49 (1.7, 3.3); <0.001 | |

| 30–34 | 0.19 (−0.3, 0.7); 0.49 | 3.03 (1.9, 4.3); <0.001 | 1.8 (1.1, 2.5); <0.001 | |

| 35–39 | 0.21 (−0.2, 0.6); 0.28 | 1.73 (1.0, 2.5); <0.001 | 2.2 (1.7, 2.8); <0.001 | |

| 40–44 | 0.51 (0.1, 0.9); =0.007 | 0.32 (−0.4, 1.0); 0.37 | 1.42 (0.9, 2.0); <0.001 | |

| 45–49 | 0.35 (0.1, 0.6); 0.02 | −0.48 (−0.9, −0.0); 0.04 | 0.42 (0.2, 0.6); <0.001 | |

| Hispanic | All (20–49) | - | - | - |

| 20–24 | - | - | - | |

| 25–29 | 1.17 (0.6, 1.7); <0.001 | 5.35 (2.7, 8.1); <0.001 | 4.8 (1.8, 7.8); =0.002 | |

| 30–34 | 0.86 (0.2, 1.6); 0.02 | 3.23 (0.9, 5.6); 0.01 | 4.78 (3.9, 5.7); <0.001 | |

| 35–39 | 0.22 (−0.3, 0.7); 0.41 | 1.68 (−0.1, 3.6); 0.07 | 3.95 (3.1, 4.8); <0.001 | |

| 40–44 | 0.33 (−0.0, 0.7); 0.07 | 1.85 (0.8, 2.9); <0.001 | 2.64 (1.9, 3.4); <0.001 | |

| 45–49 | 0.29 (−0.0, 0.5); 0.08 | 0.72 (−0.3, 1.8); 0.18 | 1.66 (0.7, 2.6); <0.001 |

| Age Group | Obesity (BMI ≥ 30) AAPC (95% CI, p-Value) | Smoking AAPC (95% CI, p-Value) | Alcohol AAPC (95% CI, p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All (20–49) | 1.49 (0.9, 2.1), p < 0.001 | −4.84 (−6.7, −2.9), p < 0.001 | 1.45 (0.4, 2.5), p = 0.005 |

| 20–24 | 1.29 (−0.8, 3.4), p = 0.19 | −6.02 (−8.7, −3.2), p < 0.001 | −0.18 (−5.4, 5.3), p = 0.91 |

| 25–29 | 2.08 (0.3, 4.0), p = 0.03 | −4.32 (−8.7, 0.4), p = 0.07 | 3.78 (−3.0, 11.0), p = 0.24 |

| 30–34 | 1.17 (0.0, 2.4), p = 0.04 | −5.25 (−10.6, 0.4), p = 0.06 | 3.67 (−0.9, 8.5), p = 0.11 |

| 35–39 | 2.82 (0.6, 5.1), p = 0.01 | −5.42 (−10.3, −0.4), p = 0.04 | 1.97 (−1.2, 5.3), p = 0.20 |

| 40–44 | 1.69 (0.3, 3.1), p = 0.02 | −4.09 (−8.6, 0.5), p = 0.08 | 0.77 (−5.3, 7.2), p = 0.75 |

| 45–49 | 0.51 (−0.6, 1.7), p = 0.39 | −4.65 (−7.3, −1.8), p < 0.001 | 0.09 (−3.0, 3.4), p = 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ayoub, N.L.; Francoeur, A.A.; Chang, J.; Tran, N.; Tewari, K.S.; Kapp, D.S.; Bristow, R.E.; Chan, J.K. Population-Level Trends in Lifestyle Factors and Early-Onset Breast, Colorectal, and Uterine Cancers. Cancers 2026, 18, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010167

Ayoub NL, Francoeur AA, Chang J, Tran N, Tewari KS, Kapp DS, Bristow RE, Chan JK. Population-Level Trends in Lifestyle Factors and Early-Onset Breast, Colorectal, and Uterine Cancers. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010167

Chicago/Turabian StyleAyoub, Natalie L., Alex A. Francoeur, Jenny Chang, Nathan Tran, Krishnansu S. Tewari, Daniel S. Kapp, Robert E. Bristow, and John K. Chan. 2026. "Population-Level Trends in Lifestyle Factors and Early-Onset Breast, Colorectal, and Uterine Cancers" Cancers 18, no. 1: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010167

APA StyleAyoub, N. L., Francoeur, A. A., Chang, J., Tran, N., Tewari, K. S., Kapp, D. S., Bristow, R. E., & Chan, J. K. (2026). Population-Level Trends in Lifestyle Factors and Early-Onset Breast, Colorectal, and Uterine Cancers. Cancers, 18(1), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010167