First Clinical Application and Validation of the Romanian BREAST-Q in Immediate and Delayed Breast Reconstruction: A Prospective Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

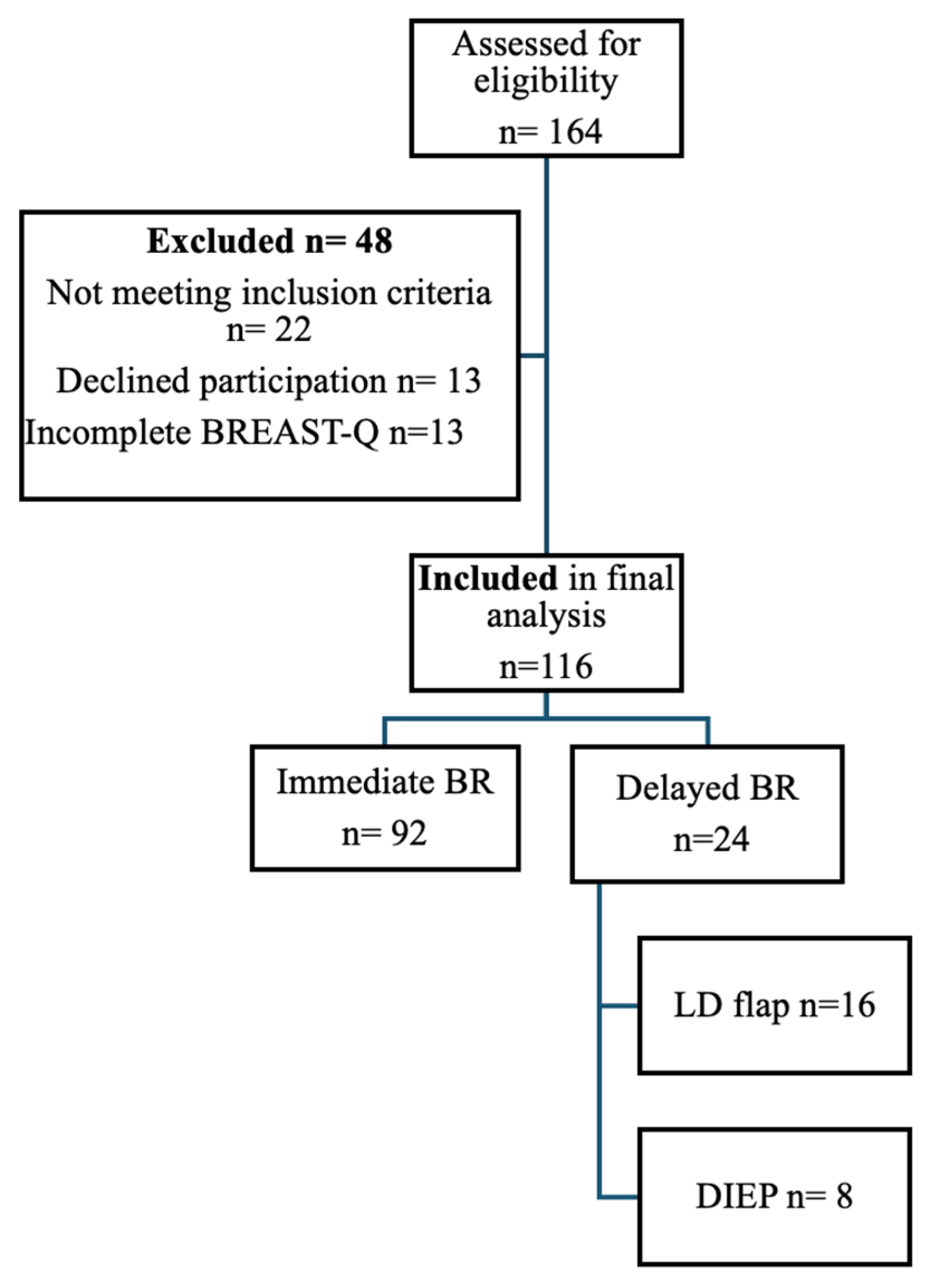

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Psychometric Validation of the Romanian BREAST-Q

3.2. Descriptive Characteristics of the Study Cohort

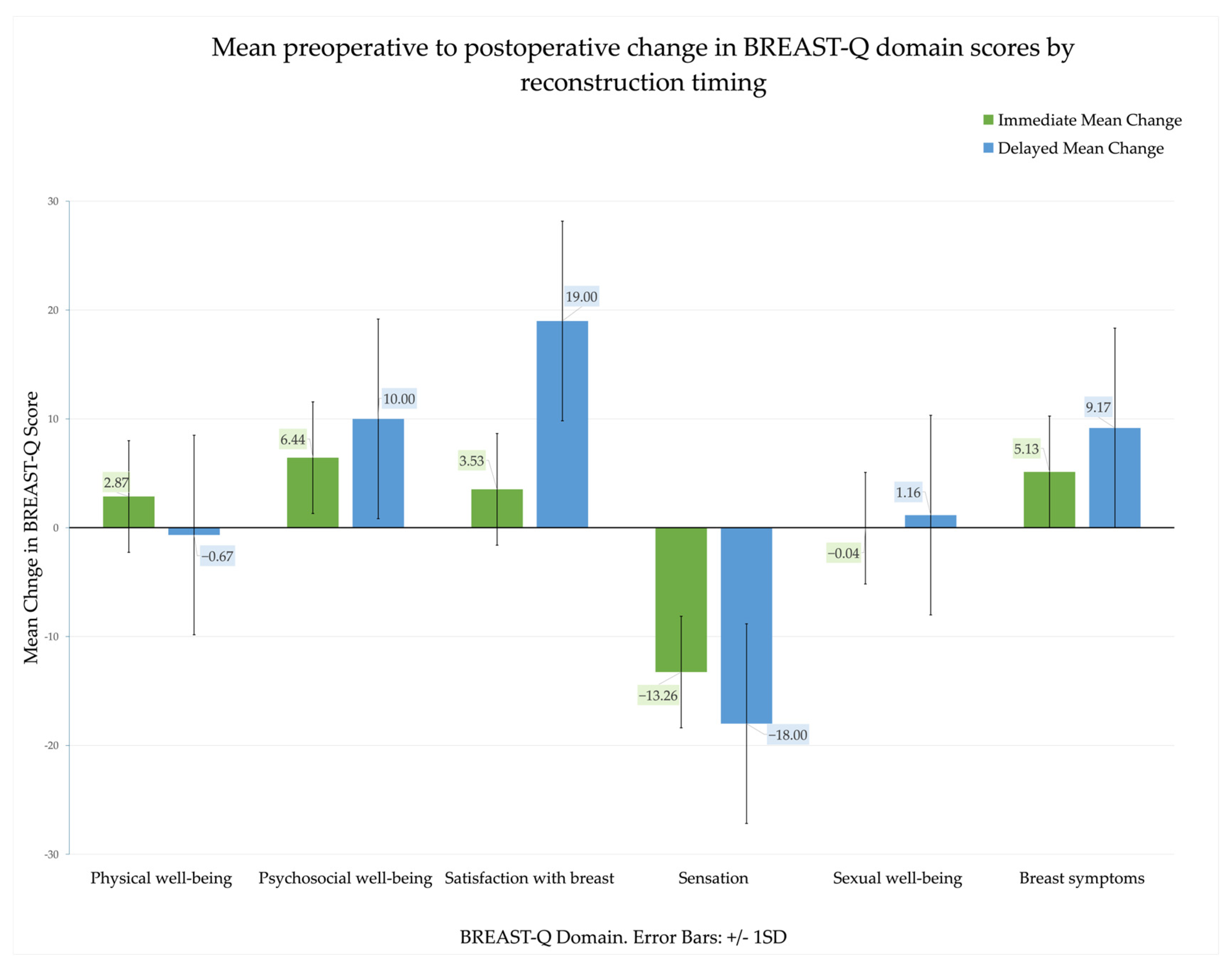

3.3. Patient-Reported Outcomes: Pre- and Postoperative Comparisons

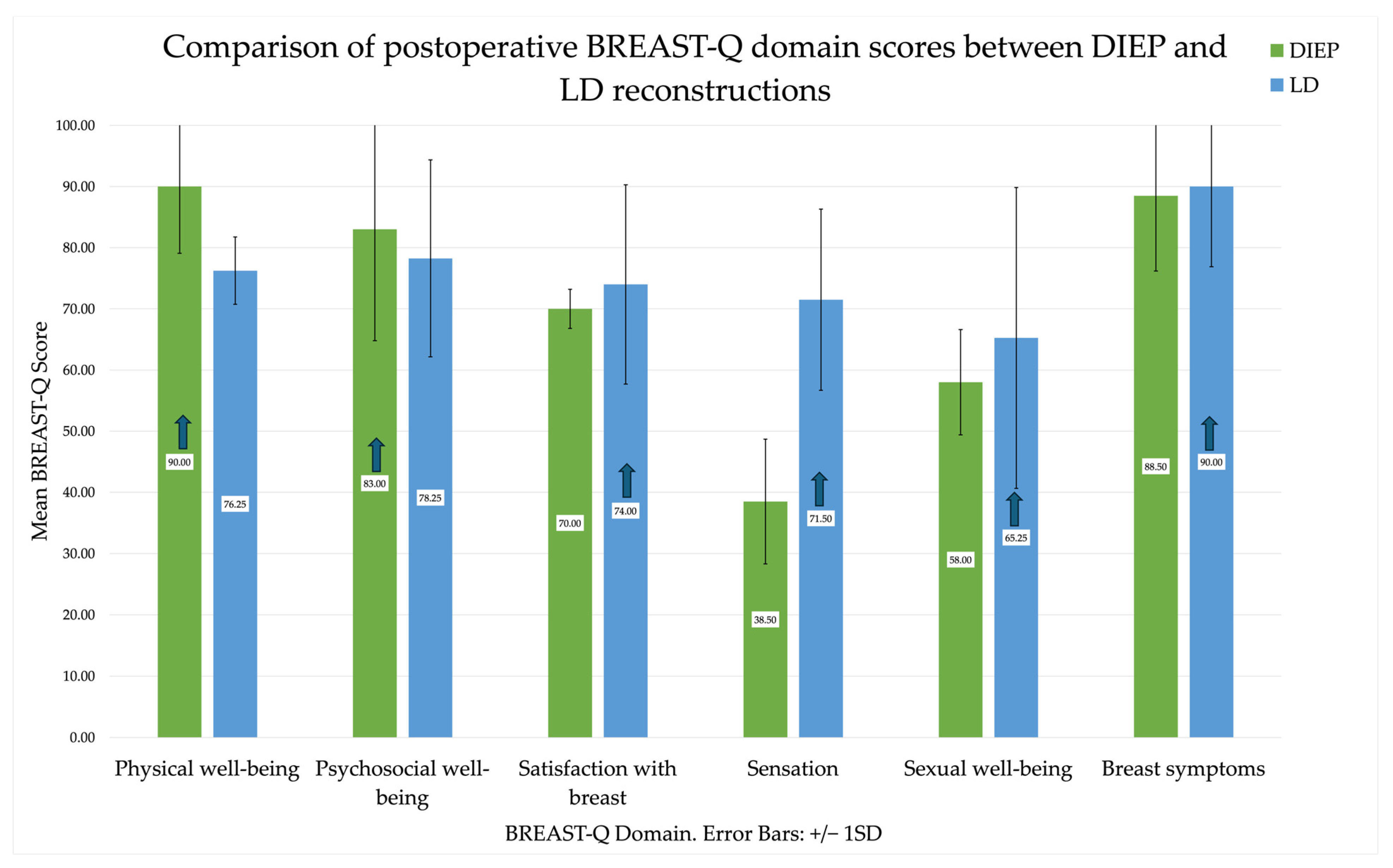

3.4. Between-Group Analyses

3.5. Predictors of QoL

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QoL | Quality of life |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| NAC | Nipple areola complex |

| LD | Latissimus Dorsi |

| DIEP | Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator |

| HTA | Arterial Hypertension |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| ALND | axillary lymph node dissection |

| SLNB | sentinel lymph node biopsy |

References

- Barofsky, I. Can quality or quality-of-life be defined? Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, W.O. State of science 1986: Quality of life and functional status as target variables for research. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Pardo, S.; Romero-Pérez, E.M.; Camberos-Castañeda, N.; de Paz, J.A.; Horta-Gim, M.A.; González-Bernal, J.J.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Simón-Vicente, L.; Fernández-Solana, J.; González-Santos, J. Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Survivors in Relation to Age, Type of Surgery and Length of Time since First Treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, A.K.; Szczesny, E.C.; Soriano, E.C.; Laurenceau, J.-P.; Siegel, S.D. Effects of a randomized gratitude intervention on death-related fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol. 2016, 35, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biparva, A.J.; Raoofi, S.; Rafiei, S.; Kan, F.P.; Kazerooni, M.; Bagheribayati, F.; Masoumi, M.; Doustmehraban, M.; Sanaei, M.; Zarabi, F.; et al. Global quality of life in breast cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, 13, e528–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, M.; Al-Wassia, R.; Alkhayyat, S.S.; Baig, M.; Al-Saati, B.A. Assessment of quality of life (QoL) in breast cancer patients by using EORTC QLQ-C30 and BR-23 questionnaires: A tertiary care center survey in the western region of Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Cancer_statistics# (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Sun, L.; Ang, E.; Ang, W.H.; Lopez, V. Losing the breast: A meta-synthesis of the impact in women breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Solbas, S.; Lorenzo-Liñán, M.Á.; Castro-Luna, G. Long-Term Quality of Life (BREAST-Q) in Patients with Mastectomy and Breast Reconstruction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 9707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phoosuwan, N.; Lunfberg, P.C. Life satisfaction, body image and associated factors among women with breast cancer after mastectomy. Psychooncology 2023, 32, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.S.; Tonsi, A.; Baig, M.K. Health-related quality of life measurement. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2008, 21, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Q.; Branford, O.A.M.; Mehigan, S.R. BREAST-Q Measurement of the Patient Perspective in Oncoplastic Breast Surgery: A Systematic Review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2018, 6, e1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusic, A.L.; Klassen, A.F.D.; Scott, A.M.B.; Klok, J.A.B.; Cordeiro, P.G.; Cano, S.J. Development of a New Patient-Reported Outcome Measure for Breast Surgery: The BREAST-Q. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009, 124, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology—Breast Cancer Version 5.2025-oct 16.2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Weick, L.; Grimby-Ekman, A.; Lunde, C.; Hansson, E. Validation and reliability testing of the BREAST-Q expectations questionnaire in Swedish. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 2022, 57, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Pérez, J.L.; Pascual-Dapena, A.; Pardo, Y.; Ferrer, M.; Pont, À.; López, M.J.; Nicolau, P.; Jiménez, M.; Masó, P.; Vernet-Tomás, M.; et al. Validation of the Spanish electronic version of the BREAST-Q questionnaire. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2023, 49, 1417–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willert, C.B.; Gjorup, C.A.; Holmich, L.R. Danish translation and linguistic validation of the BREAST-Q. Dan. Med. J. 2020, 67, A08190445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Willert, C.B.; Christensen, K.B.; Bidstrup, P.E.; Mellemkjær, L.; Gerdes, A.-M.A.; Hölmich, L.R. Psychometric validation of the Danish BREAST-Q reconstruction module. Breast 2025, 79, 103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireles, R.; Tomé, G.; Pinheiro, S.; Diogo, C. BREAST-Q Translation and Linguistic Validation to European Portuguese. Acta medica Port. 2022, 35, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.N.; Chan, S.; Bordeleau, L.; Zhong, T.; Tsangaris, E.; Pusic, A.L.; Cano, S.J.; Klassen, A.F. Re-examining content validity of the BREAST-Q more than a decade later to determine relevance and comprehensiveness. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2023, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjing, C.; Xiaoai, L.; Xiaohong, X.; Xiufei, G.; Wang, B. Meta-analysis for psychological impact of breast reconstruction in patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2018, 25, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N.; Downes, M.H.; Ibelli, T.; Amakiri, U.O.; Li, T.; Tebha, S.S.; Balija, T.M.; Schnur, J.B.; Montgomery, G.H.; Henderson, P.W.; et al. The psychological impacts of post-mastectomy breast reconstruction: A systematic review. Ann. Breast Surg. 2024, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.; Reid, A.; Columb, M.; O’Ceallaigh, S.; Duncan, J.; Holt, R. Breast-Q sensory outcomes of non-neurotized, autologous, unilateral breast reconstruction with a minimum of 3-year follow-up. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2024, 85, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svee, A.; Sjökvist, O.; Unukovych, D.; Gumuscu, R.; Moradi, M.; Falk-Delgado, A.; Mani, M. Long-term Donor Site–related Quality of Life after Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator Flap Breast Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2024, 12, e6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfstrand, J.; Paganini, A.; Grimby-Ekman, A.; Lidén, M.; Hansson, E. Long-term patient-reported back and shoulder function after delayed breast reconstruction with a latissimus dorsi flap: Case–control cohort study. Br. J. Surg. 2023, 111, znad296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanas, Y.; Tanas, J.; Swed, S.; Spiegel, A.J. A Meta-analysis Comparing Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator Flaps and Latissimus Dorsi Flaps in Breast Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2024, 12, e6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfstrand, J.; Paganini, A.; Lidén, M.; Hansson, E. Comparison of patient-reported achievements of goals and core outcomes with delayed breast reconstruction in irradiated patients: Latissimus dorsi with an implant versus DIEP. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 2023, 58, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yueh, J.H.; Slavin, S.A.; Adesiyun, T.; Nyame, T.T.; Gautam, S.; Morris, D.J.; Tobias, A.M.; Lee, B.T. Patient Satisfaction in Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction: A Comparative Evaluation of DIEP, TRAM, Latissimus Flap, andImplant Techniques. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 125, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edsander-Nord, Å.; Assareh, A.; Halle, M.; Skogh, A.-C.D. Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction in Irradiated Patients: A 12-year follow-up of Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator and Latissimus Dorsi Flap Outcomes. JPRAS Open 2024, 42, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshel, E.C.; McNary, C.M.; Barkach, C.; Boudiab, E.M.; Vega, D.; Nossoni, F.; Chaiyasate, K.; Powers, J.M. Systematic Review of Patient-Reported Outcomes and Complications of Pedicled Latissimus Flap Breast Reconstruction. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2023, 50, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlQhtani, A. Immediate Symmetrization of the Contralateral Breast in Breast Reconstruction–Revision, Complications, and Satisfaction: A Systematic Review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2024, 12, e5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, F.; Urban, C.; Zucca-Matthes, G.; de Oliveira, V.M.; Arana, G.H.; Iera, M.; Rietjens, M.; Santos, G.; Spagnol, C.; de Lima, R.S. Evaluation of Aesthetic and Quality-of-Life Results after Immediate Breast Reconstruction with Definitive Form-Stable Anatomical Implants. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137, 278e–286e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, A.E.; Kaganov, O.I.; Tkachev, M.V.; Karetnikova, N.V. Symmetrizing operations using endoprostheses in patients with breast cancer. Kazan Med. J. 2024, 105, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.C.; Hsieh, F.; Boyages, J. The effects of postmastectomy adjuvant radiotherapy on immediate two-stage prosthetic breast reconstruction: A systematic review. Plast Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 132, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammarota, M.C.; Galdino, M.C.A.; de Lima, R.Q.; de Almeida, C.M.; Junior, I.R.; Moura, L.G.; Daher, L.M.C.; Soares, D.A.d.S.; Mendonça, F.T.; Daher, J.C. Assessment of immediate symmetrization in breast reconstruction. Rev. Bras. Cir. Plástica 2017, 32, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.; Cogliandro, A.; Signoretti, M.; Persichetti, P. Analysis of Symmetry Stability Following Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction and Contralateral Management in 582 Patients with Long-Term Outcomes. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2018, 42, 936–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.A.M.; Cordeiro, P.G.; Polanco, T.; Shamsunder, M.G.; Patel, A.; Allen, R.J.J.; Matros, E.M.; Disa, J.J.; Cuaron, J.J.; Morrow, M.; et al. Association of Radiation Timing with Long-Term Satisfaction and Health-Related Quality of Life in Prosthetic Breast Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 150, 32e–41e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagusti, A.; Hontanilla, B. The Impact of Adjuvant Radiotherapy on Immediate Implant-based Breast Reconstruction Surgical and Satisfaction Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2021, 9, e3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Mao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Fan, D. The role of postmastectomy radiation therapy in patients with immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction. Medicine 2018, 97, e9548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albornoz, C.R.; Matros, E.; McCarthy, C.M.; Klassen, A.; Cano, S.J.; Alderman, A.K.; VanLaeken, N.; Lennox, P.; Macadam, S.A.; Disa, J.J.; et al. Implant Breast Reconstruction and Radiation: A Multicenter Analysis of Long-Term Health-Related Quality of Life and Satisfaction. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21, 2159–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagsi, R.; Momoh, A.O.; Qi, J.; Hamill, J.B.; Billig, J.; Kim, H.M.; Pusic, A.L.; Wilkins, E.G. Impact of Radiotherapy on Complications and Patient-Reported Outcomes After Breast Reconstruction. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, Y.; Son, Y.; Nam, T.-H.; Kang, E.; Kim, E.-K.; Kim, I.A.; Eom, K.-Y.; Heo, C.Y.; Jeong, J.H. Objective assessment of flap volume changes and aesthetic results after adjuvant radiation therapy in patients undergoing immediate autologous breast reconstruction. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyserkani, N.M.; Jørgensen, M.G.; Tabatabaeifar, S.; Damsgaard, T.; Sørensen, J.A. Autologous versus implant-based breast reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Breast-Q patient-reported outcomes. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2020, 73, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santosa, K.B.; Qi, J.; Kim, H.M.; Hamill, J.B.; Wilkins, E.G.; Pusic, A.L. Long-term Patient-Reported Outcomes in Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction. JAMA Surg. 2018, 153, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Kedde, I.L.; Sadok, N.; Krabbe-Timmerman, I.S.; de Bock, G.H.; Sidorenkov, G.; Werker, P.M. Quality of Life after Alloplastic versus Autologous Breast Reconstruction: The Influence of Patient Characteristics on Outcomes. Breast Care 2025, 20, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ticha, P.; Mestak, O.; Wu, M.; Bujda, M.; Sukop, A. Patient-Reported Outcomes of Three Different Types of Breast Reconstruction with Correlation to the Clinical Data 5 Years Postoperatively. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2020, 44, 2021–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltahir, Y.; Krabbe-Timmerman, I.S.; Sadok, N.; Werker, P.M.N.; de Bock, G.H. Outcome of Quality of Life for Women Undergoing Autologous versus Alloplastic Breast Reconstruction following Mastectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 145, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persichetti, P.; Barone, M.; Salzillo, R.; Cogliandro, A.; Brunetti, B.; Ciarrocchi, S.; Bonetti, M.A.; Tenna, S.; Sorotos, M.; Di Pompeo, F.S. Impact on Patient’s Appearance Perception of Autologous and Implant Based Breast Reconstruction Following Mastectomy Using BREAST-Q. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2022, 46, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, N.; Catanuto, G.F.; Accardo, G.; Velotti, N.; Chiodini, P.; Cinquini, M.; Privitera, F.; Rispoli, C.; Nava, M.B. Implants versus autologous tissue flaps for breast reconstruction following mastectomy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 2024, CD013821. [Google Scholar]

- Pusic, A.L.; Matros, E.; Fine, N.; Buchel, E.; Gordillo, G.M.; Hamill, J.B.; Kim, H.M.; Qi, J.; Albornoz, C.; Klassen, A.F.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes 1 Year After Immediate Breast Reconstruction: Results of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2499–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirro, O.; Mestak, O.; Vindigni, V.; Sukop, A.; Hromadkova, V.; Nguyenova, A.; Vitova, L.; Bassetto, F. Comparison of Patient-reported Outcomes after Implant Versus Autologous Tissue Breast Reconstruction Using the BREAST-Q. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2017, 5, e1217. [Google Scholar]

- Sadok, N.; Krabbe-Timmerman, I.; Buisman, N.; VanAalst, V.; DeBock, G.; Werker, P. Short-Term Quality of Life after Autologous Compared with Alloplastic Breast Reconstruction: A Prospective Study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2023, 152, 55S–68S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avino, A.; Răducu, L.; Brînduşe, L.A.; Jecan, C.-R.; Lascăr, I. Timing between Breast Reconstruction and Oncologic Mastectomy—One Center Experience. Medicina 2020, 56, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungkar, A.; Yarso, K.Y.; Nugroho, D.F.; Wahid, D.I.; Permatasari, C.A. Patients’ Satisfaction After Breast Reconstruction Surgery Using Autologous versus Implants: A Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2024, 25, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefura, T.; Rusinek, J.; Wątor, J.; Zagórski, A.; Zając, M.; Libondi, G.; Wysocki, W.M.; Koziej, M. Implant vs. autologous tissue-based breast reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the studies comparing surgical approaches in 55,455 patients. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2022, 77, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, F.D.; Levy, J.; Kim, M.; Massand, S.; Shammas, R.L.; Boe, L.; Mehrara, B.J.; Matros, E.; Nelson, J.A.; Stern, C.S. Impact of Nipple-Areolar Complex Reconstruction on Patient Reported Outcomes After Alloplastic Breast Reconstruction: A BREAST-Q Analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, K.; Cullom, M.; Nazir, N.; Butterworth, J. Patient Satisfaction Increases with Nipple Reconstruction following Autologous Breast Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 148, 177e–184e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.B.; Vingan, P.B.; Boe, L.A.; Mehrara, B.J.; Stern, C.S.; Allen, R.J.; Nelson, J.A. Satisfaction with Breasts following Autologous Reconstruction: Assessing Associated Factors and the Impact of Revisions. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 155, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, H.G.; Kwon, J.G.; Kim, E.K. Simultaneous Nipple–Areola Complex Reconstruction Technique: Combination Nipple Sharing and Tattooing. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2018, 43, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykowski, M.R.; Emelife, P.I.; Emelife, N.N.; Chen, W.; Panetta, N.J.; de la Cruz, C. Nipple–areola complex reconstruction improves psychosocial and sexual well-being in women treated for breast cancer. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2017, 70, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satteson, E.S.; Brown, B.J.; Nahabedian, M.Y. Nipple-areolar complex reconstruction and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gland. Surg. 2017, 6, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, M.; Aquinati, A.; Fordellone, M.; Carboni, N.; Marchesini, A.; De Francesco, F. Innovations in Nipple-areolar Complex Reconstruction: Evaluation of a New Prosthesis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2025, 13, e6410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.A.C.; Vizuet, I.S.; González, J.M.M.; Rivera, C.G.E.; Funes, G.E.A.; Figueroa, M.M.S. Patient Satisfaction After 3D Nipple-Areolar Complex Tattooing: A Case Series of Hispanic Women Following Breast Reconstruction Surgery. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2024, 45, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarressi, A.; Empen, L.; Favre, C. Nipple-areola complex prosthesis as a new arsenal for breast reconstruction. JPRAS Open 2023, 39, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.-J.; Lee, H.-C.; Park, S.-H.M.; Yoon, E.-S. A Comparative Study of Breast Sensibility and Patient Satisfaction After Breast Reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2022, 88, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Huang, H.; Wang, M.L.; Arbuiso, S.; Black, G.G.; Ellison, A.; Otterburn, D.M. Breast Sensation and Quality of Life: Correlating Cutaneous Sensitivity of the Reconstructed Breast and BREAST-Q Scores. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2025, 94, S276–S282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelissen, A.J.M.; Beugels, J.; van Kuijk, S.M.J.; Heuts, E.M.; Rozen, S.M.; Spiegel, A.J.; van der Hulst, R.R.W.J.; Tuinder, S.M.H. Sensation of the autologous reconstructed breast improves quality of life: A pilot study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 167, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagasia, P.M.B.; Bagdady, K.B.; Jordan, S.W.; Howard, M.A.; Fracol, M.E. Meta-analysis of Objective Sensory Outcomes From 764 Breasts Shows Superior Sensation of Autologous Reconstruction With Neurotization. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2025, 13, e6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu, S.; Chang, T.N.-J.; Lu, J.-Y.M.; Chen, C.-F.; Cheong, D.C.-F.; Kao, S.-W.B.; Kuo, W.-L.; Huang, J.-J.M. Breast neurotization along with breast reconstruction after nipple sparing mastectomy enhances quality of life and reduces denervation symptoms in patient-reported outcome: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 3235–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, J.A.; Bijkerk, E.; van der Hulst, R.R.; van Kuijk, S.M.; Tuinder, S.M. Replacing an Implant-Based with a DIEP Flap Breast Reconstruction: Breast Sensation and Quality of Life. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2023, 152, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubberman, J.M.; Van Rooij, J.A.; Van der Hulst, R.R.; Tuinder, S.M. Sensory recovery and the role of innervated flaps in autologous breast reconstruction—A narrative review. Gland. Surg. 2023, 12, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulin, A.D.; Ion, D.-E.; Avino, A.; Gheoca-Mutu, D.-E.; Abu-Baker, A.; Țigăran, A.-E.; Timofan, T.; Ostafi, I.; Jecan, C.R.; Răducu, L. Video-Assisted Mastectomy with Immediate Breast Reconstruction: First Clinical Experience and Outcomes in an Eastern European Medical Center. Cancers 2025, 17, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Domain/Statistic | Cronbach’s α | Corrected Item–Total Correlation (Range) | α if Item Deleted (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Scale | 0.947 | 0.362–0.971 | 0.938–0.952 |

| Characteristic | n = 116 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction type | ||

| ● Dual-plane implant | 92 | 79.3 |

| ● LD flap | 16 | 13.8 |

| ● DIEP flap | 8 | 6.9 |

| Timing of reconstruction | ||

| ● Immediate | 92 | 79.3 |

| ● Delayed | 24 | 20.7 |

| Symmetrization | 76 | 65.5 |

| Stage | ||

| ● Stage I | 36 | 31.0 |

| ● Stage II | 56 | 48.3 |

| ● Stage III | 24 | 20.7 |

| Histological type | ||

| ● Ductal | 92 | 79.3 |

| ● Lobular | 24 | 20.7 |

| Molecular subtype | ||

| ● Luminal A | 51 | 43.9 |

| ● Luminal B | 37 | 31.8 |

| ● HER enriched | 17 | 14.6 |

| ● Triple-negative | 11 | 9.4 |

| Chemotherapy | 76 | 65.5 |

| Radiotherapy | 60 | 51.7 |

| Unilateral reconstruction | 92 | 79.3 |

| Bilateral reconstruction | 24 | 20.7 |

| Complications | 28 | 24.1 |

| Smoking | 32 | 27.6 |

| Arterial Hypertension | 42 | 36.2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 36 | 31.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| ● Married | 96 | 82.8 |

| ● Not married | 12 | 10.3 |

| ● Widow | 4 | 3.4 |

| ● Partner | 4 | 3.4 |

| Domain | Immediate PREOP (Mean ± SD) | Immediate POSTOP (Mean ± SD) | Immediate p-Value | Immediate Effect Size (g) | Delayed PREOP (Mean ± SD) | Delayed POSTOP (Mean ± SD) | Delayed p-Value | Delayed Effect Size (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial well-being | 68.30 (17.97) | 74.74 (19.78) | <0.001 | 0.71 | 69.83 (11.40) | 79.83 (16.58) | <0.001 | 0.96 |

| Sexual well-being | 60.13 (17.59) | 60.09 (20.17) | 0.950 | −0.01 | 61.67 (19.64) | 62.83 (20.72) | 0.273 | 0.22 |

| Physical well-being | 72.48 (14.42) | 75.35 (16.62) | 0.006 | 0.29 | 81.50 (9.40) | 80.83 (9.91) | 0.612 | −0.10 |

| Satisfaction with breast | 65.04 (23.15) | 68.57 (20.69) | 0.135 | 0.16 | 58.83 (8.55) | 77.83 (12.16) | <0.001 | 1.33 |

| Sensation | 85.52 (12.17) | 72.26 (21.64) | <0.001 | −0.87 | 78.50 (8.06) | 60.50 (20.64) | <0.001 | −1.26 |

| Breast symptoms | 74.35 (13.02) | 79.48 (15.17) | <0.001 | 0.61 | 80.33 (11.37) | 89.50 (12.58) | <0.001 | 2.16 |

| Psychosocial Well-Being-POSTOP | Sexual Well-Being POSTOP | Physical Well-Being-POSTOP | Satisfaction with Breas-POSTOP | Animation Deformity | NAC Satisfaction | Sensation-POSTOP | Breast Symptoms-POSTOP | Sensation QOL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial well-being-POSTOP | PC | 1 | 0.829 ** | 0.528 ** | 0.783 ** | 0.742 ** | 0.708 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.542 ** | 0.389 ** |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Sexual well-being POSTOP | PC | 0.829 ** | 1 | 0.506 ** | 0.845 ** | 0.667 ** | 0.588 ** | 0.446 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.244 ** |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.008 | ||

| Physical well-being-POSTOP | PC | 0.528 ** | 0.506 ** | 1 | 0.556 ** | 0.439 ** | 0.555 ** | 0.235 * | 0.799 ** | 0.227 * |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.014 | ||

| Satisfaction with breast-POSTOP | PC | 0.783 ** | 0.845 ** | 0.556 ** | 1 | 0.845 ** | 0.804 ** | 0.592 ** | 0.561 ** | 0.298 ** |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Animation Deformity | PC | 0.742 ** | 0.667 ** | 0.439 ** | 0.845 ** | 1 | 0.802 ** | 0.736 ** | 0.515 ** | 0.403 ** |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| NAC Satisfaction | PC | 0.708 ** | 0.588 ** | 0.555 ** | 0.804 ** | 0.802 ** | 1 | 0.421 ** | 0.649 ** | 0.145 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.224 | ||

| Sensation-POSTOP | PC | 0.331 ** | 0.446 ** | 0.235 * | 0.592 ** | 0.736 ** | 0.421 ** | 1 | 0.177 | 0.061 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.011 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.058 | 0.514 | ||

| Breast symptoms-POSTOP | PC | 0.542 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.799 ** | 0.561 ** | 0.515 ** | 0.649 ** | 0.177 | 1 | 0.302 ** |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.058 | <0.001 | ||

| Sensation QOL | PC | 0.389 ** | 0.244 ** | 0.227 * | 0.298 ** | 0.403 ** | 0.145 | 0.061 | 0.302 ** | 1 |

| p | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.224 | 0.514 | <0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ţigăran, A.-E.; Avino, A.; Abu-Baker, A.; Timofan, T.; Ion, D.-E.; Gheoca-Mutu, D.-E.; Jecan, R.-C.; Neștianu, E.G.; Raducu, L. First Clinical Application and Validation of the Romanian BREAST-Q in Immediate and Delayed Breast Reconstruction: A Prospective Study. Cancers 2026, 18, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010168

Ţigăran A-E, Avino A, Abu-Baker A, Timofan T, Ion D-E, Gheoca-Mutu D-E, Jecan R-C, Neștianu EG, Raducu L. First Clinical Application and Validation of the Romanian BREAST-Q in Immediate and Delayed Breast Reconstruction: A Prospective Study. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010168

Chicago/Turabian StyleŢigăran, Andrada-Elena, Adelaida Avino, Abdalah Abu-Baker, Teodora Timofan, Daniela-Elena Ion, Daniela-Elena Gheoca-Mutu, Radu-Cristian Jecan, Erick George Neștianu, and Laura Raducu. 2026. "First Clinical Application and Validation of the Romanian BREAST-Q in Immediate and Delayed Breast Reconstruction: A Prospective Study" Cancers 18, no. 1: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010168

APA StyleŢigăran, A.-E., Avino, A., Abu-Baker, A., Timofan, T., Ion, D.-E., Gheoca-Mutu, D.-E., Jecan, R.-C., Neștianu, E. G., & Raducu, L. (2026). First Clinical Application and Validation of the Romanian BREAST-Q in Immediate and Delayed Breast Reconstruction: A Prospective Study. Cancers, 18(1), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010168